1. Περὶ δὲ ὧν ἐγράψατε

Some Christ-believers at Roman Corinth in the early fifties wrote a letter to Paul when he was in Ephesus, containing some questions, and most likely contestations, about Paul's teaching on sexuality, marriage, divorce, children, remarriage and ascetic practice. Their letter is long gone.

His response is emphatically not.

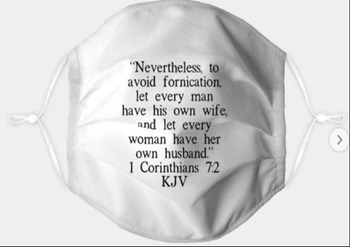

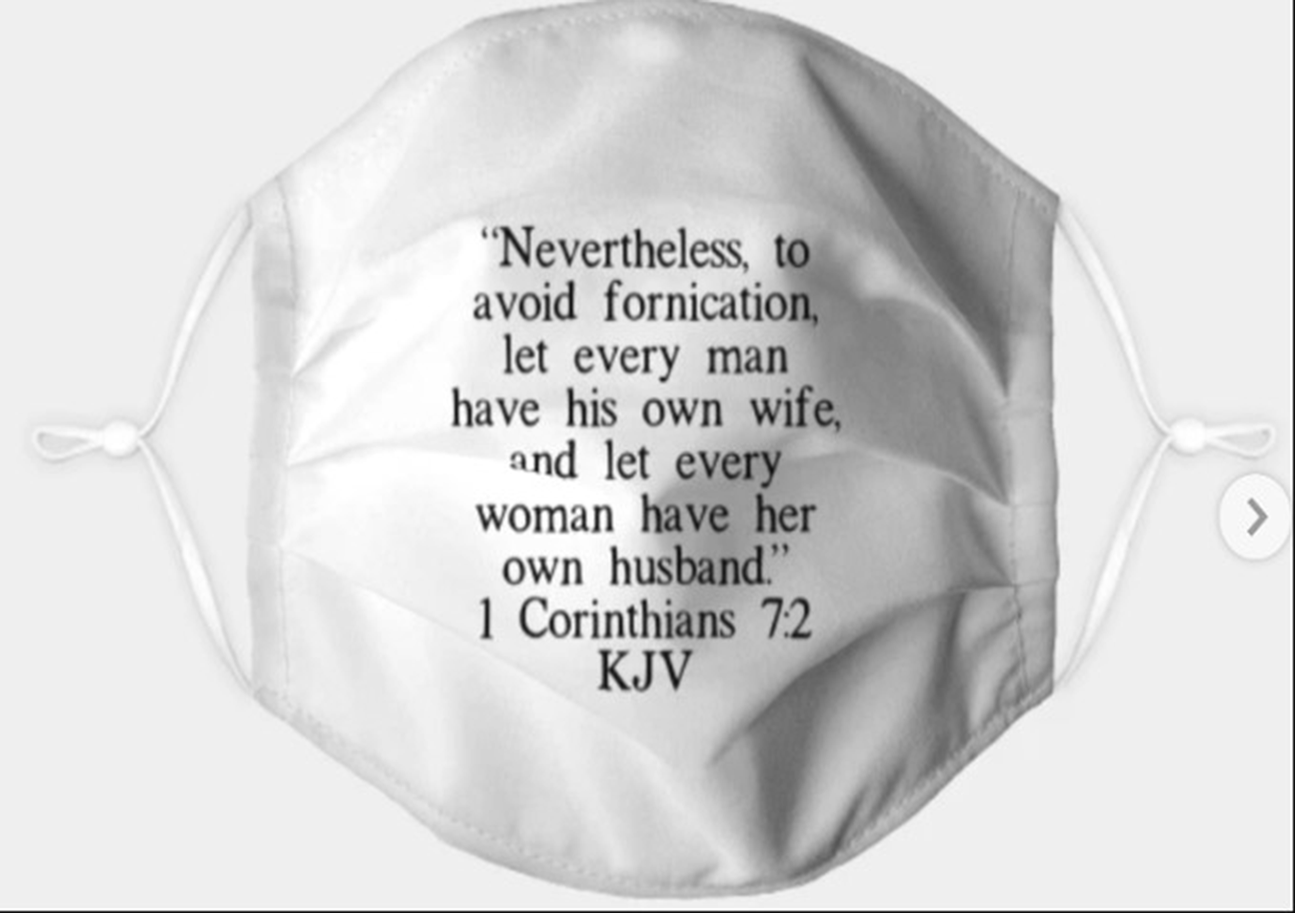

‘Now concerning the things about which you wrote’ begins a long and convoluted segment of the epistolary correspondence between Παῦλος ἀπόστολος Χριστοῦ ἸησοῦFootnote 1 and that group of people he rather grandioselyFootnote 2 refers to as ἡ ἐκκλησία τοῦ θεοῦ ἡ οὔση ἐν Κορίνθῳ. The words the Hellenistic Jewish wordsmith (Paul) offered on this occasion to address multiple scenarios and life status of gentile Christ-believers were not at all destined to solve the problems posed to him. Instead, these words have generated countless disputes, about their meaning(s) and applications to other cultural and historical contexts into which the historical-epistolary Paul would be thrust as an authoritative voice in the following decades, centuries and millennia.Footnote 3 These moments of reinterpretation and reuse range from further letters Paul wrote to these same Corinthians,Footnote 4 to the pseudepigraphical authors of Ephesians and 1 Timothy (among others), to the author of the Acta Pauli et Theclae, to Tertullian, Clement of Alexandria, Origen, Jerome, Jovinian, Augustine,Footnote 5 Thomas Aquinas, Martin Luther, Katharine C. BushnellFootnote 6 and other Christian interpreters (ancient, medieval and modern) who debated and disputed the proper Christian teaching and practices regarding sexual activity, marriage and the celibate life. This history of interpretation and reuse extends to this semiotically complicated artefact of our Coronavirus times, a face mask emblazoned with the words of 1 Cor 7.2 (King James Version), that is available online for $15 USD (Fig. 1).Footnote 7

Figure 1

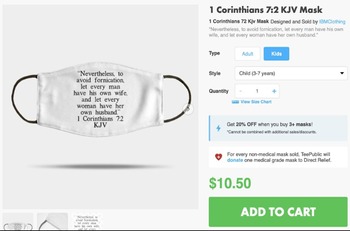

What does this composite textual-material object mean? Is the form of a face mask appropriate for bearing these words? How is its meaning different if worn by a man, a woman or a child (yes, it is available also in child sizes, fitting ages 3–7) (Fig. 2)?Footnote 8

Figure 2

Whose interpretive agency might we recover here? How much does the designer's intent, or that of the manufacturer, matter to its meaning? The intent of those who buy and wear it? The reactions of those with whom they come in contact while wearing it? Where they wear it (to school, to a dance party, to church, on an airplane, to a wedding reception)? Is it serious, or ironic? And how does the fact that the physical object on which the text is printed is a face mask relate to other commitments and convictions (medical, social, legal) about what kind of ‘protection’ such a mask affords – and from what or whom? (The same website sells other such merchandise that brings 1 Cor 7.2 KJV actively into the world as wall art, stickers, iPhone cases etc.)

The relevance of these contemporary objects to ancient biblical interpretation will I hope become clearer later in this article, but the chief point of this introduction is to emphasise the empirical point that the words Paul wrote (1 Cor 7.2–4) have been doing work in the world, in the mouths and hands of interpreters with a purpose.Footnote 9 As Elizabeth Clark has brilliantly demonstrated in her book Reading Renunciation, ‘the exhortations of patristic writers to their contemporaries intersected in unexpected ways with the varied advice Paul had addressed to specific Christian constituencies at Corinth’.Footnote 10 The utterly contingent and yet pervasive – and remarkably variable – influence of Paul's letters down through time should continually surprise us.

2. The Passage 1 Cor 7.2–4: Form and Pre- and Post-history

Before we focus upon another astonishing instance of Pauline reinterpretation, from antiquity, first let's examine those words themselves. These three rather carefully composed sentences set up a grammatical and semantic parallelism between ἡ γυνή and ὁ ἀνήρ, with form and content joining forces to reinforce with some solemnity the (surprising) gender parity – at least on the grammatical level – in the prescriptions:

διὰ δὲ τὰς πορνείας

ἕκαστος τὴν ἑαυτοῦ γυναῖκα ἐχέτω, καὶ

ἑκάστη τὸν ἴδιον ἄνδρα ἐχέτω. (1 Cor 7.2)

τῇ γυναικὶ ὁ ἀνὴρ τὴν ⸀ὀφειλὴν ἀποδιδότω, ὁμοίως δὲ καὶ

⸀ὀφειλομένην εὔνοιαν Κ Λ 104. 365. 1241. 1505 𝔐

ἡ γυνὴ τῷ ἀνδρί. (1 Cor 7.3)

ἡ γυνὴ τοῦ ἰδίου σώματος οὐκ ἐξουσιάζει ἀλλ’ ὁ ἀνήρ⋅ ὁμοίως δὲ καὶ

ὁ ἀνὴρ τοῦ ἰδίου σώματος οὐκ ἐξουσιάζει ἀλλ’ ἡ γυνή. (1 Cor 7.4)

But because of acts of sexual misconduct

Let each man ‘have’ his own wife, and

Let each woman ‘have’ her own husband

Let the husband give ‘what is owed’ to the wife; and likewise also

the goodwill that is owed

Let the wife give ‘what is owed’ to the husband

The wife does not have authority over her own body, but the husband does; and likewise also

The husband does not have authority over his own body, but the wife does.

These deliberately crafted statements represent a phenomenon we find elsewhere in Paul's letters across time, as he revised, updated or reworded his own earlier statements in light of readerly puzzlement and contestation,Footnote 11 as well as new ideas and purposes of his own. In this case, the terse, elliptical and even crude εἰδέναι ἕκαστον ἡμῶν τὸ ἑαυτοῦ σκεῦος κτᾶσθαι ἐν ἁγιασμῷ καὶ τιμῇ, μὴ ἐν πάθει ἐπιθυμίας (‘each of you to know how to have his own “vessel” in sanctification and honour, and not in lustful passion’, 1 Thess 4.4–5) has been reworked to make explicit that σκεῦος refers to the body (but whose?),Footnote 12 and that the marital/sexual possession of the partner (κτᾶσθαι, ἔχειν) is not solely commanded of men, but also of women. And yet Paul's language, with its combination of dysphemism (what does πορνεῖαι in the plural cover?) and euphemism (what do ἔχεινFootnote 13 or ὀφειλήFootnote 14 quite mean or include?) leaves much that remains underdetermined. Inscribing a sharp gender binary between men and women – even as the full letter repeatedly signals his recognition that this binary was not in fact securely in place within the Corinthian house churchesFootnote 15 – Paul formulates each of the three sentences with the ἀνήρ/γυνή pairing. Whether this is to be taken as ‘egalitarian’ or compatible with a ‘complementarian’ view (that retains the hierarchy of husband over wife)Footnote 16 remains disputed even into our day (at least in some pockets), as indeed it was already in antiquity. Paul also here extends the claim with an entirely new proposition about ἐξουσία/ἐξουσιάζειν, which coheres, if somewhat tensively, with the paradoxical theme of ‘freedom’ as ‘slavery’ ἐν Χριστῷ that he invokes frequently in this entire wider section of the long letter that is 1 Corinthians.Footnote 17 And, crucially, Paul introduces the whole under the ambiguous term πορνεία, which for him targets the specific act of sex with πόρναι, ‘female prostitutes’/‘whores’ or ‘harlots’,Footnote 18 and also can serve as a metonymy for the field of all ‘sexual misconduct’.Footnote 19

Even as we see Paul engaging in continuing self-interpretation, modification and expansion in his epistolary statements on marriage and sexual acts from 1 Thessalonians to 1 Corinthians, his own words once written down and sent to Corinth were not set in stone. Various Corinthians read them, and not all agreed (cf. 2 Cor 12.21). Pseudepigraphers sought to steer their meaning by new words of their own put in ‘Paul's’ mouth,Footnote 20 whereas the transmission history of these lines shows a remarkably successful attempt to sanitise the meaning of the ὀφειλή, ‘debt’ or ‘duty’, that Paul insisted the spouses owe each other, transforming Paul's euphemism for sexual obligations (‘conjugal rights’)Footnote 21 into a more generalised call for ‘the goodwill that is owed’ to one another (τὴν ὀφειλομένην εὔνοιαν).Footnote 22

The formality of these parallel statements in 1 Cor 7.2–4 – the first two imperatival, and the third indicative – has facilitated their being treated not as casual or contingent advice to the group that met in Gaius’ dining room in the fifties, but as Pauline directives or, even more, as rules or legal stipulations,Footnote 23 thus encouraging their trans-temporal status and reach. At the ninth meeting of SNTS in 1954, held at MarburgFootnote 24 – the site of our most recent, and still-memorably wonderful, meeting as a Society in 2019 – Ernst Käsemann wrote of ‘sentences of holy law’ (‘Sätze heiligen Rechtes’) in the New Testament, including Paul's letters.Footnote 25 Käsemann pointed to examples from before and after this chapter (1 Corinthians 7), but not these lines that are our subject today, though he could have done so. That Paul was engaging in lawgiving here about marriage (Περὶ γάμων ὁ Παῦλος νομοθετεῖ)Footnote 26 is one key assumption in the inventive act of Pauline interpretation by John Chrysostom in a homily from the last decades of the fourth century, to which we now turn.

3. John Chrysostom, Hom. 1 Cor. 7.2–4 (In illud: Propter fornicationes uxorem, etc.), CPG 4377

3.1 A Neglected Source

While New Testament scholars know well and often refer to the series of forty-four homilies by John Chrysostom on 1 Corinthians (Hom. 1 Cor. 1–44), the individual sermon on 1 Cor 7.2–4 that stands outside that famous series, bearing the traditional title In illud: Propter fornicationes autem unusquisque suam uxorem habeat, has received very little attention, even by those interested in ancient reception history.Footnote 27 This inattention in New Testament scholarship is thrown into relief in the present moment, since our homily holds some measure of prominence in one chapter of Michel Foucault's fourth volume of Histoire de la sexualité, Les aveux de la chair, posthumously published in 2018.Footnote 28 For all the interest of Foucault's reconstruction of the late antique development of a Christian τέχνη of marriage, his treatment of the homily does not give sufficient attention to the role of Pauline interpretation in it, or to the stylised rhetorical performance this homily involves, since he treats the homily as in effect a ‘traité de l’état matrimonial’ (‘treatise on the matrimonial state’, which it is not),Footnote 29 and he excerpts just a few sentences from the middle sections in forming his own argument. We can add to this that scholars of ancient Greek magic have occasionally referred to a single passage in our homily featuring the techniques of love magic used by the ‘prostitute’,Footnote 30 but no one has appreciated that the theme of the arts of love and magic unites the whole of the sermon within which this key passage must be interpreted – and hence there is much more to be said about the contribution of this homily to the study of late antique magic than has been realised. Our purpose in the present article is to introduce this source and analyse some of the main arguments of the homily in order to resource all three of these circles of scholarly discussion. It is also an opportunity to share with you, SNTS colleagues, some of the surprising things I discovered Chrysostom doing with Paul's words, as I worked to get my mind into understanding this curious late antique sermon and to translate it into correspondingly vivid English.

3.2 The ‘Occasional Homily’ and its Textual History

Chrysostom's homily Propter fornicationes uxorem, etc., which was perhaps delivered in Constantinople some time between 398 and 403,Footnote 31 was copied by Byzantine scribes in manuscripts of miscellaneous homilies and other works by Chrysostom that stand outside the full homily sets on biblical books.Footnote 32 The Greek text of this sermon was first published by Henry Savile in 1611 in his monumental ‘Eton Edition’ of Chrysostom's oeuvre in vol. v, Χρυσοστόμου εἰς διαφοροὺς τῶν ἁγίων γραφῶν περικοπὰς γνήσιοι λόγοι (‘Genuine Homilies of Chrysostom on Various Passages of the Holy Scriptures’).Footnote 33 Savile's editio princeps was based on a transcription of Codex Monac. gr. 352 (xi), fols. 54–63 (then held in Augsburg), which he had received from one of his assistants.Footnote 34 Although some additional manuscript readings of the Greek text of the homily were added by Bernard de Montfaucon in the footnotes to his edition of Chrysostom's opera omnia 1721,Footnote 35 the text in Migne, Patrologia Graeca, vol. 51 (1862) remains substantially that which Savile published in 1611. Notably, however, in 1998 Daniela Mazzoni Dami published a critical edition on the basis of her collation of eighteen medieval manuscripts.Footnote 36 Mazzoni Dami reconstructed a stemma codicum and demonstrated that Monac. gr. 352 (the basis of all earlier printed editions) is inferior at numerous points and contains frequent singular readings (often expansions), as well as significant minuses. My translation, now in press (the first complete translation of this work into English),Footnote 37 is based on the Migne text, since it remains the most widely available to scholars today, but with readings adopted from Mazzoni Dami (cited as DMD), as indicated in the notes. We shall see what a key difference her critical text makes to an understanding of this homily and its central theme and rhetorical purpose.

4. Scripture, Culture and Context

Before we (at last!) turn to the homily, we should appreciate the historical context of the act of Pauline interpretation we are about to encounter. The famous preacher, active in his home city of Antioch and later translated to the imperial capital, was one of an emerging class of orator-bishops of the post-Julianic period who used their pulpits to help craft a distinct – and, they fervently hoped, attractive – new form of urban Christianised culture, on the household and city-wide level. We cannot overemphasise the social role of oratory in the formation of Christian culture, nor of the now-existing literary culture (Scripture, commentary, homilies, a host of other genres) in their ambitions to enact on a social level what the Theodosian legislation sought to do on the legal – to enshrine Christian cultural content and values in the very heart of urban life and homes, including a kind of democratised lay semi-ascetic lifestyle. It is now widely recognised that figures such as Chrysostom did not ‘borrow’ from the rhetorical, philosophical or cultural materials of the late classical world, but they were born to them and sought in their persons, words and actions to realise some kind of synthesis of what they already inhabited. This involved much negotiation. We focus here on the role of the Pauline letters in relation to these goals, and the ways in which they provide both opportunities and challenges the preacher seeks to meet. How, in their occasional nature and gritty particularity, do these letters count as a sacred text of perduring meaning and deserved attention? How, in their simple diction and sometimes pedestrian concerns, do they match the great works of the ancient philosophical authors, as known in their entirety or through doxographic selections (the Platonic dialogues, letters of Epicurus etc.)? And how does the Christian preacher (let alone a male celibate) in the semi-public space of the basilica in the imperial city, while claiming that he is the purveyor of a new and more excellent philosophy characterised by purity, holiness and godliness, preach on a text about the unsavoury topic of πορνεία?

4.1 Words like Honey

After the anagnost has just read aloud in the synaxis the words of 1 Cor 7.1–4, Chrysostom the preacher begins:

Again today I wish to lead you to fountains of honey (πρὸς τὰς τοῦ μέλιτος πηγάς), a honey of which one can never get enough (μέλιτος οὐδέποτε κόρον ἔχοντος). For such is the nature of Paul's words (τοιαύτη γὰρ τῶν Παύλου ῥημάτων ἡ φύσις), and all those who fill their hearts from these fountains speak forth in the Holy Spirit. And indeed, the pleasure of the divine utterances makes one lose sight of even the good taste of honey (μᾶλλον δὲ καὶ μέλιτος ἀρετὴν ἀποκρύπτει πᾶσαν ἡ τῶν θείων ἡδονὴ λογίων). (§1 (51.207))Footnote 38

With exuberant words of his own Chrysostom extols Paul's words as sweet ‘fountains of honey’ of which one cannot possibly get too much. This accent on the desirability and delight of these words is meant to forestall the objection that the morning will be spent focusing on that distasteful term and reality, πορνεία. That John is likely playing on a well-known aphorism from Pindar that links too much amatory pleasure with too much honeyFootnote 39 suggests, perhaps, a bit of playfulness about how the pulpit orator will navigate the serious topic of sexual misconduct with a lighter touch about the pleasures of right romance.

After showering further words of praise on the words of Scripture (including the words of Paul), employing the self-testimony of Ps 11.7; 118.103;Footnote 40 and Proverbs 25.27, Chrysostom makes the crisp rhetorical σύγκρισις, ‘For indeed, honey is destroyed in the digestive process; but the divine utterances (τὰ λόγια τὰ θεῖα) when digested become both sweeter and more useful, both to those who possess them and to many others’ (§1 (51.208)). This metaphor for scriptural interpretation as ingestion will be developed even more graphically in John's ensuing contrast that those who eat wholesome meals (now moving from material victuals to the spiritual food of Scripture) will ‘belch forth’Footnote 41 a ‘rich fragrance’ to their neighbours. The contrast includes not only the food – material or spiritual, sweet or sour – but also the place at which one ‘consumes’ the food/words.

The same is true also with the power of words: many people belch forth [209] things akin to what they eat. For example, if you go up to the theatre (εἰς θέατρον) and you listen to ‘whorish hymns’ (πορνικὰFootnote 42 ᾄσματα), then those are the kinds of things you'll surely belch forth in the presence of your neighbour. But if by coming to church you share in the hearing of spiritual things (ἀκούσματα πνευματικά) then those are the kinds of belches you'll have as well. (§1 (51.208–9)).

4.2 Sweet Words about a Distasteful Topic

By means of a light wordplay (πορνικὰ ᾄσματα/ἀκούσματα πνευματικά), John seeks to place the discourse about πορνεία in the theatre,Footnote 43 and the words of Scripture – even when they are about πορνεία – in the ἐκκλησία. The quality of words, the contexts in which they are spoken, and by whom they are said, are essential, the preacher insists from his pulpit in the basilica:

In assemblies out there in the world,Footnote 44 even if occasionally something useful might be said, on many sordid occasions the majority of people hardly utter a single thing that's salutary (μόλις ἓν ὑγιὲς οἱ πολλοὶ φθέγγονται).Footnote 45 But in the case of the divine Scriptures, it's the exact opposite. You'll never hear a single wicked word in them, but all the words are full of salvation and profound philosophy (πονηρὸν μὲν οὐδένα οὐδέποτε ἀκούσῃ λόγον, πάντας δὲ σωτηρίας καὶ πολλῆς γέμοντας φιλοσοφίας). Such indeed are the things that were read to us today. And what are these? ‘Now concerning the things about which you wrote to me’, he says, ‘it is good for a man not to touch a woman. But on account of sexual misconduct, let each man have his own wife and let each woman have her own husband’ [1 Cor 7.1–2].Footnote 46 Paul lays down laws about marriage (περὶ γάμων ὁ Παῦλος νομοθετεῖ),Footnote 47 and he's not ashamed (καὶ οὐκ αἰσχύνεται) nor does he blush (οὐδὲ ἐρυθριᾷ). And rightly so! For his Lord esteemed marriage and wasn't ashamed of it, but even honoured the practice with both his presence and a gift – for indeed, he brought the greatest gifts of all to the wedding by changing the nature of water into wine [cf. John 2.1–12]. If that's so, then rightly his servantFootnote 48 doesn't blush when laying down laws about these things (εἰκότως οὐδὲ ὁ δοῦλος ἐρυθριᾷ περὶ τούτων νομοθετῶν).Footnote 49 (§2 (51.210))

In denying the apostolic blush, the celibate preacher may well be deflecting his own (and likely forestalling a congregational complaint). But with Pauline παρρησία he, too, will engage the unsavoury topic of πορνεία as full of πολλὴ φιλοσοφία.

4.3 Marriage as a pharmakon

Chrysostom offers his thesis for the homily in a concise rhythmic formulation of his own:

Οὐ γὰρ πονηρὸν ὁ γάμος πρᾶγμα,

ἀλλὰ πονηρὸν ἡ μοιχεία,

πονηρὸν ἡ πορνεία⋅

γάμος δὲ πορνείας ἀναιρετικὸν φάρμακον. (§2 (51.210))

For marriage isn't a wicked practice,

but what's wicked is adultery,

what's wicked is sexual misconduct.

And marriage is a potion that destroys sexual misconduct.Footnote 50

While the contrast between marriage and πορνεία comes right out of 1 Corinthians 7, Chrysostom brings the Pauline idea into a magical register when he infers (presumably taking into account also 1 Cor 7.9b: κρεῖττον γάρ ἐστιν γαμῆσαι ἢ πυροῦσθαι, ‘it is better to marry than to be set on fire’) that in the eyes of the apostle the malady of πορνεία is so severe that it requires a potion (φάρμακον)Footnote 51 designed to target and destroy it (ἀναιρετικόν). While the Pauline text of 1 Cor 7.2–4 includes both women and men in each line, Chrysostom choses to focus his sermon on the men in his congregation – even as he talks about women and in the presence of women – depicting the men as the especially weak link in the marriage.Footnote 52 Why are these men at such risk? As with his author, Paul, for John the threat of πορνεία can encompass a wide field of forms of sexual misconduct,Footnote 53 even as it is etymologically related to that ready-made stereotypical villain, the πόρνη.Footnote 54

4.4 Γάμος and ἔθος

The allusion to the wedding feast at Cana in John 2 directs the preacher first to marriage ceremonies (the term γάμος of course refers to both the ceremony and the institution). This is a pet peeve of the preacher, since here is both a social space and a cultural form where convention – and not his version of Christianity – holds sway. After first complaining that the priest (unlike the Johannine Jesus) is not invited to the wedding, John gives his own negative description of the various ritual actions within a conventional late antique wedding that are intended to curry favour with the gods and fates for the couple's prosperous future:Footnote 55 ‘whorish hymns (τὰ πορνικὰ ᾄσματα), effeminate songs,Footnote 56 disorderly choruses, shameful words, the satanic procession, the commotion, the pealing laughter, and the rest of the unseemly behaviour’ (§2 (51.210)).Footnote 57 Chrysostom urges his congregants to drive all these things out of the wedding celebration. His anticipated lack of success in this endeavour is shown in his quotation of the expected rejoinder: ‘But it's our custom (ἔθος)!’Footnote 58 Chrysostom tries lamely to find ancient biblical precedent for decorous weddings by alluding to Isaac marrying Rebecca and Jacob marrying Rachel, but, perhaps recognising that he is skating on thin ice here (what about Leah in the bed trick in Genesis 29?!),Footnote 59 he doesn't tarry here, instead giving an even more vivid description of the riotous goings-on at weddings:

… flutes, pan pipes, cymbals and leaping about like asses,Footnote 60 and all the rest of the present unseemly behaviour were nowhere in sight [in the biblical examples]. But the choral singers in our day sing hymns to Aphrodite, and on that very day they sing about serial adultery, defilement of marriages, unlawful lovers and illicit couplings, and many other songs filled with impiety and shame. And after a drunken bout and so much unseemly behaviour, they parade the bride around publicly with shameful words.Footnote 61 (§2 (51.211))Footnote 62

We can see here the stubborn hold of an unquestioned mainstay of late antique classical culture when it comes to celebrating love and nuptials,Footnote 63 hardly touched by the decades since the imperial sponsorship of Χριστιανισμός under Constantine and his successors. This includes practices and speech acts that are thought to set the pair on an auspicious path – such as the use of insults and curses as apotropaic of evils and misfortunes (for instance, the famous Fescennini versus),Footnote 64 and of sexually graphic speech to encourage procreation.Footnote 65 Chrysostom terms these acts, and the hymns calling on Aphrodite and Hymen and other traditional gods to favour the couple, ‘summoning demons’ (τοὺς δαίμονας καλεῖν, §2 (51.211)), thus identifying the traditional marital rites as, in his view, magical incantations of the worst sort.

As a rejoinder to being on the losing end of this argument about age-old rituals, the preacher tries to urge the inauguration of a new custom (συνήθεια) along the lines of Matt 22.1–14 // Luke 14.16–24, of inviting the poor to the weddingFootnote 66 instead of the musicians, actors and other hired performers whom Chrysostom despises when they are in the theatre and whose appearance in congregants’ homes at the time of the wedding celebrations he finds abominable.Footnote 67 Again, Chrysostom voices an anticipated objection from the congregants: but having the poor at a wedding would be a bad omen for the couple,Footnote 68 presaging their own future life in poverty. Weddings should feature auspicious rites that summon the gods of love and prosperity to the side of the couple. Here Chrysostom – who is as convinced as those he seeks to correct that ritual can bring good or bad fortune – tries to flip the cultural script and argue that the presence of these performers at the wedding (rather than the poor, who embody Christ's own presence)Footnote 69 is precisely what will lead to the demise of the marriage:

… what is a portent of utter unpleasantness and countless calamities (ἁπάσης ἀηδίας καὶ μυρίων ἐστὶ σύμβολον κακῶν) is not the poor and widows being fed but the ‘pansies’ (μαλακοί)Footnote 70 and the ‘whores’ (πόρναι). For often the ‘whore’, having from that day forward taken the groom captive (αἰχμάλωτον λαβοῦσα) from his friends, has gone off and extinguished the loving passion (ἔρως) he had for his bride, dragged away his goodwill (εὔνοια), destroyed his love (ἀγάπη) before it has been inflamed, and sown in him the seeds of adultery (μοιχείας σπέρματα).Footnote 71 Fathers should be afraid of these things, and, even if for no other reason, they should prevent mimes and dancers from coming to wedding celebrations. (§3 (51.212))

By ‘whores’ John may be referring to higher-class ἑταῖραι (‘courtesans’), but more likely this reflects his assumption (shared with others in the long-standing majority culture) that mimes and pantomimes who perform at wedding receptions are all sexually promiscuous and of dubious morals.Footnote 72 Chrysostom's generally misogynist (and resolutely androcentric) views resonate easily with the cultural stereotype of the πόρνη as trafficking in magical techniquesFootnote 73 – ironically, the more aggressive or ‘masculine’ onesFootnote 74 – setting her sights on the newly married man and with her aggressive arts of seduction taking him captive, extinguishing his ἔρως for his wife, uprooting his ἀγάπη before it even gets kindled and causing him to forsake the εὔνοια the wife deserves.Footnote 75 Later in the homily, in which he rather theatrically seeks to warn off the men in his congregation, John will get even more technical about the specific magical practices the imagined πόρνη performs:

Many of the bad men who have consorted with ‘whores’ have come to bad ends because of it, once they've submitted to the manipulative craft (περιεργία)Footnote 76 of these women who make ‘whores’ of themselves (ὑπὸ τῶν πορνευομένων γυναικῶν). Out of their ambition to separate him from the wife who shares his home and has received his pledge of fidelity, and to bind him completely by lust for them (τῷ … αὐτῶν ἔρωτι προσδῆσαι τέλεον), those women have set in motion forms of magical trickery (μαγγανεῖαι), concocted love charms (φίλτρα)Footnote 77 and devised many acts of sorcery (γοητεῖαι). Then, after throwing him into such painful sickness and handing him over to rot and waste away, and lassoing him with countless ills, they've carried him away from the present life. So, man, if you don't fear hell, fear their magical spells! (Εἰ μὴ φοβῇ τὴν γέενναν, ἄνθρωπε, τὰς γοητείας αὐτῶν φοβήθητι). For by this debauchery (ἀσέλγεια) you cause yourself to lose God as an ally (σαυτὸν … ταύτης ἔρημον ποιήσῃς τῆς τοῦ Θεοῦ συμμαχίας), and you strip yourself of assistance from on high (ἡ ἄνωθεν βοήθεια).Footnote 78 At that very moment, the ‘whore’ – having taken you captive (λαβοῦσά σε) by licentiousness, summoned her demons (τοὺς αὐτῆς καλέσασα δαίμονας),Footnote 79 stitched her magical spells (τὰ πέταλα ῥάψασα)Footnote 80 and set in motion her schemes – so easily stands victorious over your salvation (μετὰ πολλῆς τῆς εὐκολίας περιγίνεταί σου τῆς σωτηρίας).Footnote 81 (§5 (51.216))Footnote 82

With this litany of magical terms (περιεργία, μαγγανεῖαι, φίλτρα, γοητεῖαι), John depicts the πόρνη using the full panoply of erōs-magic, summoning a kind of curse that inflicts the victim with the painful and even deadly disease of love.Footnote 83 Given this threat, the preacher insists, inviting such figures into a wedding celebration isn't just a harbinger of problems down the road, but the πόρνη's presence at the wedding actually sets in motion her power to identify her victim and then seduce the new husband through her powerful love magic. By offering this operatic tale,Footnote 84 the celibate preacher solemnly forewarns that a marriage begun this way can only end badly.

4.5 The Prophylaxis

In the face of such a supernaturally charged threat, what is the weakly and vulnerable new husband to do? He needs to summon powers of his own against the assaults of the πόρνη's power, a counter-charm. The preacher recites 1 Cor 7.2 once more, and then prescribes:

I would wish each man to inscribe (ἐγγράψαι) this passage [1 Cor 7.2] on his mind (διάνοια) and usher his own brideFootnote 85 into the house of the bridegroom using these words (μετὰ τούτων τῶν ῥημάτων), and to have this very statement carved (ἐγκεκολάφθαι) on the walls of the house (εἰς τοὺς τοίχους τῆς οἰκίας), on the bridal chamber (εἰς τὸν θάλαμον) and on the marital bed itself (εἰς αὐτὴν τὴν εὐνήν): ‘But on account of sexual misconduct, let each man have his own wife, and let each woman have her own husband’ (1 Cor 7.2).Footnote 86

This fascinating sentence, so important for understanding the discourse on magic that Chrysostom engages in throughout this homily – and so insistent as it is upon rendering text in more permanent and public media – had ironically been lost to scholarship by a homoeoteleuton Footnote 87 in the sub-archetype of medieval Chrysostomic manuscripts on which all modern printed editions were based. But it has been restored thanks to the critical edition of Mazzoni Dami in 1998.Footnote 88

Echoing the diction and directive of Deut 6.6, καὶ ἔσται τὰ ῥήματα ταῦτα, ὅσα ἐγὼ ἐντέλλομαί σοι σήμερον, ἐν τῇ καρδίᾳ σου καὶ ἐν τῇ ψυχῇ σου (‘and these words which I am commanding to you today shall be in your heart and in your soul’), and the injunction in Deut 6.9 for the words of the Shema to be γραφθῆναι ἐπὶ τὰς φλιὰς τῶν οἰκῶν ὑμῶν καὶ τῶν πυλῶν ὑμῶν (‘written on the doorposts of your houses and your gates’), Chrysostom calls for the words of 1 Cor 7.2 to be inscribed on multiple surfaces and spaces. First, these words are to be for the groom a kind of mental amulet, etched into his mind and purpose.Footnote 89 Second, they are to be used as substitute lyrics for the bawdy songs and hymns to Aphrodite and Hymen that accompany the bridal procession and involve the wedding party marching around the outside of the bridal chamber with song and speech, cheering the couple on during their first marital night together.Footnote 90 And, even more, like the words of Deut 6.4–5 that proclaim the total love of the Israelite for the one true God, Paul's carefully cadenced words of 1 Cor 7.2 are to be inscribed as a talismanic house phylactery,Footnote 91 not on the doorposts and gates, but on increasingly focalised spaces of the private home in which the newly married couple will dwell: the outer walls of the house,Footnote 92 inside the bridal chamber itself, and lastly on the very bed on which the marriage will be consummated. Chrysostom has hereby transformed Paul's 1 Cor 7.2 into a veritable Shema of sex.

But this is not all. Later in the homily Chrysostom sketches in even more specific detail how the now married man, when faced with a moment of acute temptation, is to ritually summon the power of 1 Cor 7.2 for this apotropaic purpose:Footnote 93

Sing these words as an incantation to yourself every day (ταῦτα καθ’ ἑκάστην ἔπᾳδεFootnote 94 σεαυτῷ τὴν ἡμέραν τὰ ῥήματα).Footnote 95And if you perceive that lust (ἐπιθυμία) for another woman is being aroused in you (ἐγειρομένη ἐν σοί), and concomitantly your own wife seems repugnant (ἀηδής) to you, go into your bedroom (θάλαμος), unroll this book (τὸ βιβλίον ἀναπτύξας τοῦτο)Footnote 96 and, making Paul your go-between (λαβὼν Παῦλον μεσίτην), continually sing these words as an incantation (συνεχῶς ἐπᾴδων ταῦτα τὰ ῥήματα) and thereby extinguish the flame (κατάσβεσον τὴν φλόγα). (§4 (51.215))

On this vivid scenario, the Pauline words of 1 Cor 7.2, present always in the mind and daily on the lips of the husband, as well as (putatively) carved into the house, can be even more directly activated when there is a special need, that is, when the erōs-magicFootnote 97 of the ‘other woman’ (i.e. the πόρνη) is producing the effect that it should, and is alluring the husband to her with lust (ἐπιθυμία), while at the same time turning his proper romantic desire for his wife into outright disgust. Now the Pauline words of 1 Cor 7.2 are present in yet another physical form – the ‘book’ (τὸ βιβλίον τοῦτο)Footnote 98 itself – a physical object that can be activated even more intensively for defensive purposes by turning to the exact page, encountering ‘Paul’ in it and revoicing Paul's words as a protective charm, with the written text physically standing between oneself and the threat.

Most interesting here is Chrysostom's designation of ‘Paul’ as a μεσίτης, ‘go-between’, or ‘intermediary’. Chrysostom is perhaps deliberately ambiguous about the identity of the other party participating in this act of mediation involving the vulnerable husband. If it is the ‘other woman’ or πόρνη, Paul is an intermediary who does not facilitate contact but instead blocks it, in the physical form of the book of his words (hence one might translate: ‘positioning “Paul” between her and you’). But that is not how the term μεσίτης is usually used. The phrase λαμβάνειν μεσίτην can refer to establishing a ‘go-between’ between lovers.Footnote 99 On this rendering, John means that Paul acts as the ‘intermediary’ facilitating the proper sexual and romantic love between the husband and his wife, in the θάλαμος to which he retreats, and where this talismanic text is supposed to have already been inscribed on the room and the bed itself (per the restored passage quoted above, p. 136).Footnote 100

In favour of the second option is Chrysostom's very next sentence, about the effects of this apotropaic ritual with the Pauline βιβλίον:

And in this way, also, your wife will again be more desirable (ποθεινοτέρα) to you,Footnote 101 since no lust (ἐπιθυμία) is dragging away the goodwill (εὔνοια) you have for her. And not only will your wife be more desirable (ποθεινοτέρα), but you in turn will seem more dignified (σεμνότερος) and less servile (ἐλευθεριώτερος). (§4 (51.215))

On this reckoning, Paul's words in 1 Cor 7.2, activated in the talismanic ritual, serve not only as a protective spell extinguishing the ‘flame’ of illicit ἔρως,Footnote 102 but also as a kind of love charm that turns the husband's romantic desire back onto its proper target, his wife, now rendered more desirable (ποθεινοτέρα). According to Chrysostom's vivid description, this ensures the husband's obedience to the Pauline law of obligatory spousal goodwill (τὴν ὀφειλομένην εὔνοιαν, 1 Cor 7.3 𝔐), and in turn makes him a proper object of her love. He had hinted at this already just moments earlier when he cast σωφροσύνη as the best allurement to romance for the married couple: ‘it's impossible for a licentious (ἀσελγής) and promiscuous (ἀκόλαστος) man to love (φιλεῖν) his own wife, even if she's more beautiful (εὐμορφοτέρα) than all other women. For love (ἀγάπη) is born from chasteness (σωφροσύνη), and from love come countless good things (ἀπὸ δὲ ἀγάπης τὰ μυρία ἀγαθά)’ (§4 (51.215)).

4.6 Final Movements and Rituals

In the last part of the homily, the preacher returns to the theme of ‘honey’ with which he opened, quoting the warning in Prov 5.3–4 that the πόρνη's lips taste like honey, but her kiss is bitter, containing an unseen and deadly poison (ἰός). After a closing argument drawing once again on Proverbs (5.18–19) and framed from the husband's point of view, extolling via vivid metaphor the virtues of sexual love with one's wife – ‘a filly of one's own fancy’, ‘drinking from one's own well’ – Chrysostom returns to the Shema of sex of 1 Cor 7.2 and leads his congregation in a ritual enactment of the charm that will protect the Christian marriage:

Thus, let's continually sing these words as an incantation (ἐπᾴδοντες οὕτω διατελῶμεν) both to ourselves and our wives (καὶ ἑαυτοῖς καὶ ταῖς γυναιξίν). And hence I, too, shall conclude with these words: ‘But on account of sexual misconduct, let each man have his own wife, and let each woman have her own husband. Let the husband give the goodwill that is owed to his wife, and likewise the wife to her husband. The wife does not have authority over her own body, but the husband does; likewise also the husband does not have authority over his own body, but the wife does’ [1 Cor 7.2–4]. By keeping these words constantly in our minds in the marketplace and at home, day and night, at table and in bed, and everywhere, let's practise them ourselves, and let's instruct our wives (καὶ τὰς γυναῖκας παιδεύωμεν)Footnote 103 both to say them to us and to hear them from us (καὶ πρὸς ἡμᾶς λέγειν, καὶ παρ’ ἡμῶν ἀκούειν), so that, after living the present life with due chasteness (σωφρόνως), we might attain the kingdom of heaven, by the grace and loving kindness of our Lord Jesus Christ, through whom and with whom be glory to the Father, together with the Holy Spirit, forever and ever. Amen. (§5 (51.218))

The Pauline text as chanted in the synaxis becomes the peroration of the homily, and the explicit call for the performative communal liturgy to be carried out into the world. Giving only minimal lip service to the parallelism of women and men in the Pauline passage, in his own words throughout this homily Chrysostom has focused almost exclusively on the men and their potential for straying. In the self-appointed guise of one championing the cause of the wife against betrayal at the hands of her husband, Chrysostom relies routinely on a misogynist stereotype of the πόρνη, her rival. In the role of marriage counsellor-cum-liturgist, the unmarried ascetic leads the final love chant and instructs it for ‘our wives’, even as in his own person he defies the very ‘commands’ he leads them in singing.Footnote 104

5. Conclusion

5.1 John Chrysostom, Paul and ‘Christian Love Magic’

Paul's words, first dictated and written down in the early fifties, then copied by scribes down to Chrysostom's time, revoiced by the anagnost in the liturgy in the 380s or 390s, and by the preacher himself in his own words, have been (re)cast as an apotropaic spell, performative words that, activated orally and in material form, are said to have the potential to act and protect – if used as instructed. We know that Chrysostom himself was well aware of the practice of amulets among Jews, ‘pagans’ and Christians, from a number of well-studied passages in his oeuvre,Footnote 105 as well as the remarkable narrative he tells in Hom. Ac. 38.4–5 (60.273–76) of having found a magical handbook floating in the Orontes in his youth.Footnote 106 All of this means that what Chrysostom has done in the homily we have been investigating here is not an accidental straying into the land, logic and vocabulary of the magical arts, but an intentionally devised face-off between rival ritual technologies for securing a safe and prosperous marriage, both in the nuptials and thereafter. This historical-contextual evidence fully confirms our literary analysis of the repeated pairings of good and bad love magic, and the way the argument of the whole homily unfolds.

But is it legitimate to call what Chrysostom engages in here discourse about ‘Christian love magic’? There is of course historic debate about whether to use the term ‘magic’ at all in scholarly work on ancient religions, or to use the term only in an emic mode (when the ancient sources use the term) or etic mode (with a modern analytical definition for heuristic purposes).Footnote 107 I use the term ‘love magic’ as one key aspect of what Chrysostom does here because there is clear correspondence in technical vocabulary and contextual meanings of specific magical spells (φίλτρα, πέταλα, μαγγανεῖαι), and the introduction of rituals meant to counter them in forms both verbal and material. I also use it to describe the wider cultural arena within which he seeks to develop a τέχνη of Christian marriage (with a nod to Foucault), and also to draw due attention to the surprising lengths to which he goes to push these Pauline verses into the lives of his congregants. Indeed, what Chrysostom is doing in this highly rhetorically stylised homily is positioning himself precisely between the emic and the etic – in the mimetic, if you will. He deprecates by lurid stereotypical description the magic arts of the extreme outsider, the πόρνη, on the one hand, while also offering sanctioned protective rituals that mimic hers and those of the traditional wedding ceremonies,Footnote 108 both in terms of apotropaic spells and a more positive love magic for the Christian couple defined by σωφροσύνη as their romantic charm, even as it is marriage itself, he claims, that is the φάρμακον that will destroy the demonic force of πορνεία.

There is some risk to Chrysostom's mimicry, which renders his proposals at the least ambiguously poised.Footnote 109 Although Chrysostom himself (the emic perspective) would certainly not accept the label, what he is calling for here is a form of ‘scripture magic’, defined by David Frankfurter (the etic perspective) as ‘a charismatic medium of a Great Tradition [as defined by the anthropologist Robert Redfield], both in the “performance” of the scribal ritual expert who delivers efficacious passages of scripture and in the client's encounter and use’.Footnote 110 This definition maps very well onto the ways in which the institutional authority, Chrysostom, is in this homily designing and legitimating ritual practices with the authorised scriptural text for his congregants to use in their daily lives and homes. We could add to this that Chrysostom deliberately invokes a doubly scriptural idiom for these written and spoken incantations – not only the rhythmic words of the Pauline verse, but also of the Shema – in his attempt to authorise and normalise the practice. And this performance by Chrysostom also fits well the paradigm of ‘miniaturisation’ of ritual to which theorists of ancient magic have pointed,Footnote 111 here from the formal reading, homiletic interpretation and final communal ‘chant’ of 1 Cor 7.2 in the liturgical synaxis in the ecclesia, to its reinvocation and reactivation in progressively tighter spaces, down to the bedroom of the private home.

But this leaves us with a key question, circling back to the 2021 face mask imprinted with 1 Cor 7.2 KJV with which we began: just how seriously did Chrysostom expect his congregants to take this injunction to chant 1 Cor 7.2 as a spell for protection, to use it as lyrics for songs at wedding ceremonies, to keep it in book or amulet format in the bedroom, or inscribe it as a phylactery on their homes or furniture? To date, no amulet has been found that contains 1 Cor 7.2 – although there are very few extant ancient Christian amulets that include Pauline texts at all (rather than gospels or psalms, for instance).Footnote 112 Perhaps, in the process of negotiated Pauline meaning(s) that began way back with the Corinthians, Chrysostom's audience just didn't buy it?

5.2 New Testament Studies as a Unified Field

Aside from being the first SNTS Presidential address to date on πορνεία, what does this study out of my current research say about New Testament scholarship, now and into the future? I close by offering a few reflections on my own view of the field for consideration, discussion and debate among us.

New Testament studies is not just a collection of various approaches and methodologies, but is a unified field that at its best defies separation into sub-specialities. Although unified, New Testament studies cannot stand on its own apart from early Christian literatureFootnote 113 more broadly, the study of Second Temple and post-Second Temple Judaisms, imperial period history and classical literature, religion and culture. So many of the most interesting questions of the field, and its promise for original contributions to humanistic learning, require the integration of:

Philological precision on the word, phrase, sentence, paragraph and document level, and attention to the art and science of translation, which is always an act of interpretation. Words matter, and words do not stand still.Footnote 114

Textual criticism and manuscript studies as both central for the construction(s) of the objects of our study and as an invaluable record of reception and repackaging.

Historical contextualisation that includes history of religions and history of culture information and analysis, as well as intellectual (i.e. theological, philosophical) and social histories.

Reception-history of the multimedia and variably purposed reinterpretations and reuses of the New Testament texts, and the ways in which in each moment of interpretation a human agent is making deliberate choices that complexly interact with other interpreters and proposals, and their own purposes, audiences and thick contexts.

Literary finesse both in reading the New Testament documents themselves and textual forms of interpretation down through history (including our contemporaries); this includes the need to offer fresh readings of whole texts, and not just mine the documents for nuggets taken out of context and applied to more general questions. Whole and part must always be carefully and consciously navigated, all the more so now that digital reading and search habits heavily favour the part over the whole.

Methodological sophistication as one of the humanistic disciplines (committed to the quest for truth, justice, beauty, learning, understanding and new knowledge), consistently questioning the philosophical and epistemological bases of our work, and attuned to and actively engaged with its political, ethical, social and ideological ramifications, past and present, in a non-simplistic way, as we, along with our contemporaries in and outside the academy seek critically to test and discern how the past has and continues to provide resources for human flourishing or for oppression, dignity or debasement.Footnote 115

Hermeneutical suppleness about how meaning is constructed in each act of interpretation (including our own), and ways in which there is a continual play between the old and the new, the clear and the unclear, the expected and the utterly unexpected. Our task is not to lock-box meanings of those words, but to locate and analyse each act of New Testament composition and interpretation as one that involves conscious decisions by human actors with a purpose, whether an audacious Hellenistic Jew named Paul proclaiming the crucified Jesus as Messiah, a late fourth-century homilist faced with a problem text and an unpopular pastoral crusade against well-entrenched cultural convention or a twenty-first century face mask designer looking for buyers seeking protection in uncertain times. We should continue to be surprised.

Competing interests

The author declares none.