Introduction

The legal services market in England and Wales possesses two peculiarities. One is its plethora of legal professions.Footnote 1 The other is an attenuated concept of ‘practice of law’ confined under the Legal Services Act 2007 (the Act) to six ‘reserved’ activities.Footnote 2 This paper proposes a reconceptualisation of one of these: the right of audience. It uses the rights theories of Hohfeld and Waldron to interrogate three critical interlocking factors:

(a) ‘rights’ to perform;

(b) acquisition of competence; and

(c) regulatory accountability during (DTE)Footnote 3 or after the event (ATE).

In the existing model these are parcelled out between stakeholders in an interlocking tension field that lends itself to a Hohfeldian analysis. The novel analysis in this paper, however, offers a reconceptualisation of rights of audience as one of Waldron's ‘responsibility rights’ that combines, rather than separates, those key factors. This reconceptualisation is needed urgently, given the Solicitors Regulation Authority's (SRA's) proposal to abandon mandatory before the event (BTE) education and assessment of witness examination for solicitors. It is nevertheless generalisable to all advocates as a more robust means of guarding against incompetent advocacy.Footnote 4

The ‘right of audience’ is defined by the Act as the right to ‘appear before and address a court, including the right to call and examine witnesses’;Footnote 5 that is, the right to be ‘heard’ by a judge. Even Mayson, a strong critic of the rationale for the statutory six, acknowledges the logic of regulating this public good activity, which presents different, and possibly greater, risks than the others.Footnote 6 Advocacy is ‘an area of practice where people are often vulnerable and the stakes are high’.Footnote 7 The logic of treating it as a reserved activity necessarily entails the state managing the risk. It does so by assuring it is performed to a minimum level of competence, the threshold for which might be high, and that there is accountability for failure to meet it. In England and Wales the ultimate accountability is, via the individual regulators, to the Legal Services Board (LSB) created by the Act. However, the principle that only ‘lawyers’ are enabled to carry out the task on behalf of others is an international norm, at least in the common law world where the adversarial oral tradition intensifies the risk.

Clearly, not all forms of advocacy in all kinds of hearing are objectively of equal risk. Its highest risk aspect, and the specific focus of this paper, appears in the final clause of the definition. This describes the key function of the advocate in an adversarial trial: witness examination. Poor witness examination in any court has the capacity to impact adversely on litigants’ livelihood, family, liberty and, in some jurisdictions, life. More legally significant trials are reserved to the higher courts where rights of audience are, for solicitors, more sparingly granted.Footnote 8 However, the vast majority of Anglo-Welsh criminal trials are held in the magistrates’ courts, with substantial potential for adverse impact on defendants and victims. Here, solicitors carry out most of the advocacy.Footnote 9 Advocacy is a significant societal good and licensure to perform it is of considerable reputational and financial advantage to individual lawyers. Pressure to take on such work when a lawyer is not competent to do so (or does not know whether or not they are) might, therefore, be considerable. The advocacy literature focuses on education, practice and strategy and on ethics.Footnote 10 There is some discussion of the extent to which any profession, or quasi-profession, might have a claim to the right (in particular in the higher courts).Footnote 11 There is discussion of regulation and regulatory models.Footnote 12 There are multiple reports on quality of performance.Footnote 13 What is missing is not only consideration of the interaction of the various factors and stakeholders, but a more fundamental analysis of the nature of the right itself. In particular, how lawyers not competent to act are restrained from acting in the first place, rather than sanctioned after the harm has been done.

The risk is that framing this activity as a ‘right’ encourages it to be seen as an absolute entitlement, to be zealously guarded by individuals and the different professions. This detaches it from being contingent on competence. The distinction between the two is placed into context in England and Wales by a radical change to the qualification system for solicitors. The right to appear in a criminal trial in the magistrates’ court or a civil trial in the county court is, at present, automatically conferred on every solicitor on the day they qualify. This is reinforced by the SRA competence statement which includes the ability to ‘[deal] with witnesses appropriately’Footnote 14 as an expectation of every solicitor at the point of qualification. The right, with a DTE obligation to maintain that standard,Footnote 15 is then retained by the 195,821 practising solicitorsFootnote 16 for the remainder of their careers unless a ‘condition on practice’ removing the right is imposed on them as an ATE sanction.Footnote 17

At present, all aspiring solicitors are required to undergo BTE education in advocacy, including witness examination, before they qualify. This at least has some pretension to permit them to acquire competence, or, at least, awareness of the significance of the task. The SRA's recently approved proposals abandon this in favour of a single centralised assessment in two parts (Solicitors Qualification Examination, SQE) from the autumn of 2021.Footnote 18 SQE 2 includes advocacy but will exclude witness examination. This despite influential views that the highest risk legal activities merit BTE, as well as DTE and ATE, regulation.Footnote 19 Recent consultation by the SRA discussed below, makes it clear that control over solicitors’ advocacy standards in lower court trials is now to be achieved only through the Standards and Regulations 2019Footnote 20 (DTE) and their enforcement processes (ATE).Footnote 21 These place the responsibility to act only if competent on individual solicitors and their employers. It is not unusual for professional competence statements and codes of conduct to refer to such a responsibility, although the SRA is unusual in the vigour with which it embeds the competence statement into its own disciplinary strategy. Incompetence becomes, therefore, an ethical and not just a malpractice issue. The SRA does so, however, whilst depriving those solicitors of any mandatory BTE education on which to base their evaluation of competence. This is true of other niche areas of solicitors’ practice, but of no others that are simultaneously reserved activities, frequently high risk, and consciously included in the competence statement.

There is, therefore, a serious question about whether the new model can prevent solicitors performing witness examination incompetently, even if it is effective at ATE punishment. Only a fundamental reconceptualisation of the right of audience, prioritising personal responsibility for competence over entitlement to act as an integral part of the right itself, can effectively address that question.

In order fully to understand the significance of both the SRA's plans and the need to reconceptualise rights of audience more fundamentally, it is necessary to consider each of three key factors: rights, competence and regulatory accountability. The way in which they interact separates competence from rights and accountability in a way that Hohfeld would, as we will see, describe as molecular. It is assumed that the three factors, each separately controlled by different stakeholders, hold each other in check, keeping, as it were, the table steady. This paper proposes that the table should, rather, have a single, central, solid leg.

Context: the plethora of professions and the deregulated landscape

Although it is argued that rights of audience need to be reconceptualised in any event, the stakes are significantly higher for the SRA. Any difference in infrastructure – such as the SQE – that can be perceived as weakening a profession's claim to a reserved activity will be exploited by the others clamouring for the same work. The heterogeneity of the competitive market highlights differences – real or assumed – in a way that Hohfeld would recognise. It is therefore first important to understand how the state has come to this divisive position.

Much has changed since the position noted by Burrage where barristers and solicitors acted to reduce their respective remits, limiting themselves to work that each profession felt was honourable and reinforced its claim to professional status.Footnote 22 The Act's directive to ‘promot[e] competition in the provision of services’Footnote 23 mandates competition not only within, but also between, professions. It is therefore in the interests of each profession to enable its members to carry out as much work of as many different ‘reserved’ kinds as possible and to exclude others by aggressive branding and the operation of market forces.Footnote 24

Practitioners and their regulators must also, however, obey the Act's other objectives including ‘encouraging an independent, strong, diverse and legal profession’. The use of the singular ‘profession’ is ironic in the light of the mandate to compete. There has not been a single legal profession in England and Wales since the medieval notaries were joined by the fourteenth century Common Bench. Solicitors emerged in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The early inter-profession negotiation noted by Burrage resulted in the solicitors’ monopoly over conveyancing (real property transactions) and the Bar's position as referral-only advocacy specialists.Footnote 25 Other professions followed.Footnote 26 The onset of the competitive environment is most strikingly marked by the creation in the mid-1980s of the licensed conveyancer profession, specifically to break the solicitors’ conveyancing monopoly.Footnote 27 A series of reports attacking legal monopolies from 2001 onwardsFootnote 28 resulted in the Act.

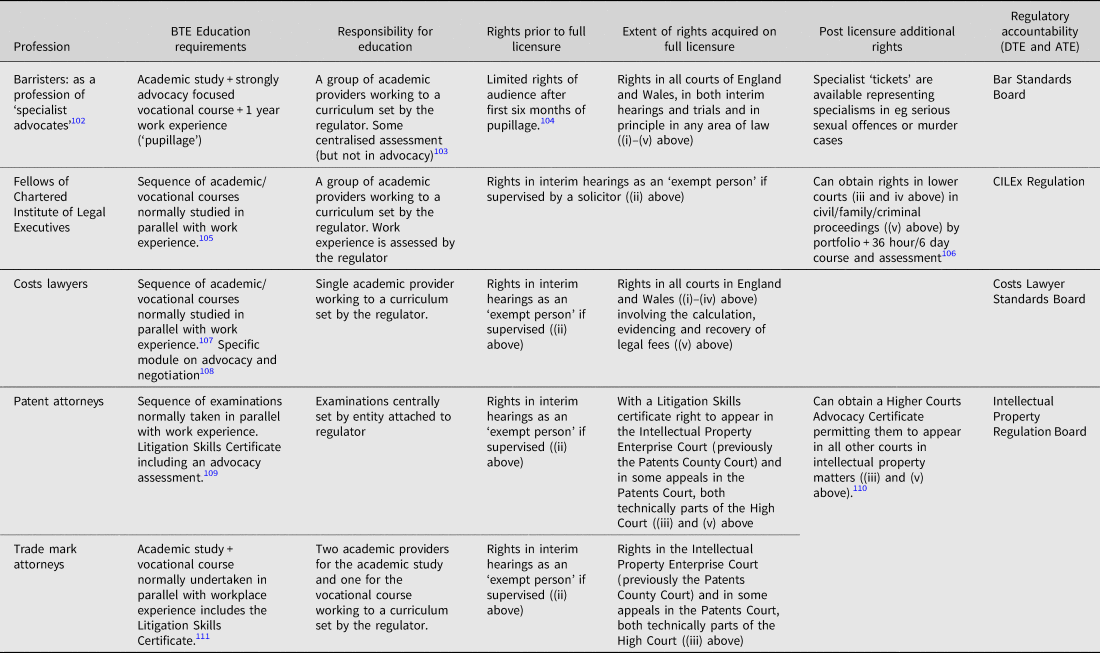

The result is that rights of audience are possessed under the Act by all barristers, all costs lawyers, some legal executives, all patent attorneys, all solicitors and all trade mark attorneys, although in the case of all but the Bar and solicitors, restricted to particular areas of law (see Table 1). The extent to which there is a supporting BTE infrastructure to equip members of those professions with the competence to perform adequately – by contrast with an ATE regulatory accountability that punishes for lack of competence – varies considerably. The focus is, again, on heterogeneity and on the separation of the three key factors. In the context of the SRA's plans, this fine categorisation of rights also serves to limit the circumstances in which aspiring solicitors, deprived of mandatory BTE education, can acquire competence (and awareness of what competence entails) by experiential learning in the workplace.

Table 1. patterns of regulatory governance of competence in witness examination

The first key factor: rights to perform

The heterogeneity in regulation of rights of audience began with Courts and Legal Services Act 1990, s 27,Footnote 29 which permitted ‘authorised bodies’ to grant rights of audience to their members. Section 32 recognised the existing rights of solicitors and their clerksFootnote 30 in the lower courts and s 33 those of barristers. More controversially, however, solicitors were granted the opportunity to acquire rights in the higher, Crown Court, by s 67 and the (then) immunity of advocates from claims in negligence and contract was extended to non-barrister advocates by s 62.Footnote 31 The Bar, as might be expected, fought a considerable battle against this incursion into its territory.Footnote 32

The Act follows a similar model. Each of the six regulators listed in Schedule 4 may cause its members to be ‘authorised’ persons and exercise rights of audience in accordance with its own remit and regulations, overseen by the LSB.

In addition to mandating competition, then, and facilitating the different regulators in developing their own BTE training and licensing requirements, codes of conduct and continuing education systems (DTE) and disciplinary procedures (ATE), the Act further fractures rights of audience into the following categories:

(i) judicial model;

(ii) venue (for example, in open court or in chambers);

(iii) seniority of court;

(iv) the nature of the hearing;Footnote 33

(v) field of law; and combinations of all of these.

The Act defines and controls the distribution of the right but says nothing explicit about competence or the relative risk of each category. It is the regulators who determine who is licensed and what BTE education they require. Judges do not themselves sanction weak advocates except through the wasted costs process,Footnote 34 but may refer to a regulator, who can. There is, however, evidence that some judges do not feel this is effective, whilst others believe that it is for the market to discriminate against weak advocates.Footnote 35

In the interstices of this regulatory maze, it is important to understand how limited the circumstances will be in which aspiring solicitors can develop towards competence once the BTE requirement has gone.Footnote 36 First, the Act's reservation of rights of audience does not apply to tribunals or to arbitration. Tribunal litigants can be represented in final hearings where witness examination takes place by students and trainees.Footnote 37 Few will have such opportunities.

Second, as supervised ‘assistants’ of regulated lawyers,Footnote 38 trainees are ‘exempt persons’ when they appear in some chambers hearings. This will not normally include witness examination.

A third possibility could provide experience of witness examination in court trials although, again, opportunities will be scarce. Its regulatory model also, to some extent, blends right to act, competence to act, and accountability in the way advocated by this paper. The court has power under the Act to hear otherwise unauthorised or non-exempt advocates on a case-by-case basis.Footnote 39 Although the ‘right of audience’ is in concept a right vis-à-vis a court, these are the only circumstances where the right is actually within the gift of the court. In the absence of conventional methods of holding poor advocates to account through regulators or insurance,Footnote 40 the risk is controlled by this limitation to the case at hand. In simple cases, where an articulate volunteerFootnote 41 helps out as a ‘McKenzie Friend’,Footnote 42 this is uncontroversial. There is, however, a cadre of professional McKenzie Friends, operating commercially or in the interests of a pressure group.Footnote 43 Some may have received BTE training.Footnote 44 In order to maintain their business, they may seek to use permission granted in one case as leverage to be granted rights in others.Footnote 45 Consequently rights will only be granted to a repeat or ‘professional’ McKenzie Friend in exceptional circumstances.Footnote 46 An important criterion in this treatment has been an unfavourable contrast with the mandatory BTE training undergone by authorised advocates from which competence is inferred:

It is desirable that members of the public, … know that they are briefing a representative who has been properly trained and approved by an appropriate accredited professional body. … To permit any person unknown to the Court with no legal training and no professional accreditation to represent a litigant may be unfair to the litigant, unfair to the other parties and unfair to the Court.Footnote 47 (emphasis added)

Under the new regime, as we shall see in the next section, the training and competence of newly qualified solicitors in lower court witness examination will be no less variable between individuals than it is for McKenzie Friends. The other authorised professions have kept responsibility for BTE competence in the hands of the regulator. If the courts retain the test above, these professions will have a far greater claim – what Waldron might describe as an ‘interest’ – than solicitors to be distinguishable from McKenzie Friends.

The next section demonstrates the divergence in the place of acquisition of competence in the regulatory system between the different professions as a precursor to the theoretical reconceptualisation advocated in this paper

The second key factor: acquisition of competence

A rational response to society's recognition of the risk inherent in trial advocacy is to dedicate a particular kind of BTE training, assessment and DTE and ATE regulation to it.Footnote 48 This could be achieved either by confining it to those professions who undertake to train their members (regulation by title) or independently licensing individuals to perform it (regulation by activity), possibly using a homogenous set of standards or competences. Even Mayson, arguing for radical review in legal services regulation, sees a role for the professional titles.Footnote 49 He is, however, far more interested in regulation of activities, particularly of those, amongst which he counts advocacy and litigation, that are of higher risk. This combination of competing professions and regulation by activity does not have a happy history. In 2013 there was an attempt to achieve homogeneity in criminal court advocacy for barristers, Chartered Legal Executives and solicitors by assessment leading to licensure for different levels of court and complexity of case. This failed, at least arguably due to inter-professional competition.Footnote 50 It was sufficiently controversial to go to the Supreme CourtFootnote 51 and finally expired in 2018Footnote 52 with the LSB promising to hold individual regulators to account in the future for managing the risks.Footnote 53

What remains then is demonstrative of the deliberate competitive environment and the legislative history continued under the Act where regulation is largely by title. Considerable emphasis is placed on BTE training and assessment, mandated and quality assured by the relevant regulator. The way in which this is managed, however, demonstrates divergence and heterogeneity. This is mapped in Table 1. The complexity with which responsibility for the three key factors is allocated to different actors lends itself to a Hohfeldian analysis, with which we can subsequently compare the more coherent Waldronian alternative.

Table 1 demonstrates that the national model for equipping lawyers with both information about the skill and baseline competence in it – mirrored in the other UK nations and in many other Commonwealth countries – is for advocacy to be a component, and, in the case of barristers, an overwhelming component, of a BTE vocational course. The responsibility for this is, however, spread across different stakeholders. The resource-intensive simulation experience is delivered by course providers (often universities) and they (normally) assess, subject to regulation and quality assurance by the regulator and financing by the student.Footnote 54 This simulation, coupled with further exposure in the workplace, is then supplemented by ATE sanction. An additional sanction may be a claim by the client in tort or contract. Regulatory accountability is through the relevant professional code relating to: (a) specific ethical failings;Footnote 55 or (b) generic competence in service provision, sometimes supplemented by additional ethical obligations for advocates.Footnote 56

Between 1993 and 2021, the solicitors’ profession used this model. Aspiring solicitors took a vocational Legal Practice Course (LPC) with a mandatory advocacy component.Footnote 57 Some LPCs add elective advocacy modules but the mandatory component is normally limited to activities within (iv) above. In 2013, the LETR large-scale review of education and training across all the regulated professions expressed concern about this. Solutions suggested, but not implemented, were to train and license lower courts rights of audience separately or to move them into a reinforced work experience requirement.Footnote 58

The level of skill achieved in the LPC is intended to be supplemented by:

(a) experience, as an ‘assistant’ ((ii) above), in a tribunal or by observing others, during the two-year period of work experience;Footnote 59 and

(b) 18 hours of mandatory simulated ‘advocacy and communication’ experience during the Professional Skills Course (PSC).Footnote 60 This is taken during the two-year period (and paid for by the employer). It culminates in a ‘skills appraisal’ that is a formative, rather than summative evaluation.Footnote 61

Quantitatively, then, solicitors already spend less classroom time than do barristers or legal executives to acquire identical lower court rights of audience. Even this, however, may have some informational value about what witness examination is, how it differs from other forms of advocacy, and the risks inherent in underperformance.

Qualitatively, clearly, mere classroom time is no guarantee of competence in the messy and pressured real-world environment. The expectation, therefore, is that it will be built on during the two-year period of work experience at item (b). Its desired outcome is that ‘On completing the training period, trainee solicitors should be competent to exercise the rights of audience available to solicitors on admission’. They should be provided with tasks that ‘enable them to grasp … dealing with witnesses appropriately’.Footnote 62 It is acknowledged that such experience will normally be as an ‘assistant’ ((ii) above) – although, as we have seen, this is unlikely to include witness examination – or through observation, which might.Footnote 63 While observation is a key learning tool,Footnote 64 and may facilitate ‘grasping’, this is not the same as being able to perform. Evidence suggests that trainee solicitors do not feel that the normal range of work experience equips them to be competent in advocacy.Footnote 65

A great deal of weight, therefore, currently rests on the PSC. Although it is almost certainly unconscious, the distinction between ‘rights’ and ‘competence’ factors is apparent in the difference between the PSC's rights claim that successful students should ‘be able to exercise the rights of audience available on admission’ and the demand that on qualification they should be ‘competent’ to do so (emphasis added). In the SRA's new model the level of competence expected at qualification in all the activities listed in the competence statement, is ‘Acceptable standard achieved routinely for straightforward tasks …’.Footnote 66 What is ‘straightforward’ is clearly subject to argument. Because witness examination appears in the competence statement, however, we must assume that the scope of competence includes appearing in at least some kinds of trial in the lower courts.

In the new regime, however, the PSC is to be abandoned.

A mandatory two year period of work experience is retained, but is diluted in the sense that it must merely allow candidates ‘opportunities to develop’ ‘some or all’ of the required competences (presumably, therefore, the minimum is two).Footnote 67 Although SQE 2 is pitched, unlike the LPC, at the level expected at the point of qualification, many will take it before then.Footnote 68 As a measure of actual competence at the temporal point of qualification, it is, therefore, critically flawed.

At a global level, many legal professions whose members acquire rights of audience on qualification are not required to undergo BTE training or assessmentFootnote 69 in advocacy. In England and Wales, however, the stakes are rather different. The other professions with whom solicitors are in direct, state-mandated competition expend time and resource in developing and assessing the competence of their advocates using BTE vocational education. If solicitors could compare badly with McKenzie Friends in the new regime, how much worse might they compare with a member of another profession who can point to BTE training and assessment in witness examination as a visible contribution to acquisition of competence?

Mandatory BTE education sets the conditions for competence and provides information about the demands of performing the skills well, rather than conferring total competence itself. The regulator, if called upon to sanction an advocate, is entitled to rely on those benchmarks as a starting point. The advocate cannot claim not to know what competent performance entails. In relation to witness examination, that message has hitherto been transmitted to aspiring solicitors through the LPC and PSC and, with less assurance of clarity, through the two-year period prior to qualification. The shift in the SRA's proposals will mean that it will not be the regulator, or an educational provider, who sets the BTE standard, but the individual and their employer. Whether that standard matches the SRA's expectations will be a question of ATE investigation.Footnote 70 In the next section, we consider the final key factor in the network and, in particular, the SRA's justification for shifting the responsibility for acquiring competence in witness examination back to the profession.

The third key factor: regulatory accountability

All regulators retain ATE responsibility for sanctioning advocates who perform unethically or incompetently. The previous section discussed the relationship between stakeholders and the acquisition of competence. As shown in Table 1, some professions regulate by title and train all members accordingly. Others regulate by activity, linking BTE training to specialist licensure. The recent SRA consultation is telling in how it responds to the suggestion that specialist licensure for all rights of audience might be appropriate for solicitors:

20 … [We] will require all intending solicitors to undertake a rights of audience assessment before admission.

21. We recognise that solicitors have full trial rights in the lower courts and have considered whether we should include witness handling in the SQE assessment. We have concluded that we should not.Footnote 71 It would be disproportionate, expensive, and out of step with most solicitors’ work.Footnote 72 … we will therefore be piloting a role-play exercise in the form of a plea-only or interim application.

22. Against this background, we have considered whether we should place a restriction on solicitors’ rights of audience in the lower courts until they have been assessed in witness handling. We take the view that we should not do so. Evidence of concerns relates to criminal advocacy practised in higher courts and in the youth courts, not the magistrates’ court. The risk of a broad restriction on practice in lower courts is that it could discourage solicitors from practising advocacy, and therefore restrict competition and restrict access to justice.

23. Instead we will propose relying on solicitors’ and firms’ obligations in our code of conduct to undertake only the work which they are competent to perform. We will supplement this with guidance and support, and rigorous enforcement action where standards fall short.Footnote 73

There is no indication that the SRA changed its principles as a result of the consultation.Footnote 74 The effect is that lower court trial advocacy is to be relegated below all other reserved activities, none of which are treated in this way in the SQE. It means that an element of the competence statement that is the ostensible benchmark for performance at qualification is not tested. Different logics are, of course, at play in paragraphs 21 and 22–23. These seem to be driven by a pragmatic need to compromise on the costs and complexity of BTE assessment when many solicitors do not appear in trials whilst, in the competitive market, being unwilling to let the rights – the entitlement – go. This is treated as the last word on the matter.

The first argument is the cost-benefit analysis. The majority of advocacy in magistrates’ courts is carried out by solicitors, generally from smaller or specialist firms.Footnote 75 Nevertheless, the SRA argues, the subcategory of lower court trial advocacy is carried out by a minority group of solicitors and complex and expensive to assess, therefore, as a lesser risk, it will not be assessed. The SRA has, however, undercut its argument about risk by changing its position on youth court advocacy (a lower court). This, as indicated above, it initially treated as a matter of sufficient concern to absorb into the BTE regulation of advocacy in the higher courts.Footnote 76 This contrasts with the approach taken by the Federation of Law Societies of Canada in 2012 when developing a competence statement. A series of proposed competences were rated for both frequency and risk.Footnote 77 Whilst some of the suggested infrequent competences were discarded, others were included in the competence statement because of their risk. The competence ‘Conduct simple hearing or trial before an adjudicative body’ passed the frequency threshold in most, but not all, jurisdictions but was also assessed as moderately or highly serious in risk.Footnote 78 It was, therefore, included. It is, however, only fair to say that proposals for a national assessment of this competence statement were later shelved, partly on feasibility grounds.Footnote 79

The second logic is closer to the language and objectives of the Act. Despite being a minority interest, solicitors should not be prevented from competing with other lower court advocates and providing services to clients. No mention of assuring or measuring BTE competence here, and, indeed, given the argument in the preceding paragraph, it would be difficult to make one. The language is of rights rather than competence, with the restraining factor the regulatory accountability articulated in paragraph 23 as the obligation to exercise the right only if competent to do so. As we have seen, this responsibility is placed on the lawyer and his or her employer through DTE regulation leading to the risk of ATE sanction. In the decision to act, they are second-guessing the subsequent opinions of the enforcing regulator.

The SRA's shift of the responsibility for competence in witness examination from BTE to ATE sanction fundamentally changes the pull and push of the complex regulatory network. There will, therefore, shortly be two models in operation. The norm for the regulation of rights of audience is one in which stakeholders engage in a complex push and pull arrangement of BTE, DTE and ATE regulation. This is best described by a Hohfeldian analysis that maps how those pushes and pulls operate to restrain what might otherwise appear to be an absolute entitlement. The SRA's shift changes the pull and push in a way that, it is argued, fundamentally weakens it. The final part of this paper will evaluate the potential for a Waldronian approach to remedy that weakness, both for solicitors and all advocates.

A rights analysis of rights of audience

A significant aspect of the rights debate is the taxonomical identification of hierarchies: the other rights or considerations that can ‘trump’ rights. In our context this means identifying what, if anything, can prevent a solicitor from exercising their right to conduct witness examination in the lower courts in the absence – from 2021 – of BTE experience.

Hohfeld's structural analysis of rights is one of form, and has not been without criticism and revision.Footnote 80 In its simplest form, however, it is useful as a way of mapping how responsibility for the three key factors is normally divided between stakeholders.Footnote 81 There are two primary kinds of obligations: the claim-right/duty and the privilege/no claim dyads, subject to alteration or removal by the secondary dyads of power/liability and immunity/disability. Hohfeld is not interested in the processes, such as BTE education or assessment, that confer rights, or in how rights are exercised except as (under)performance triggers the secondary dyads. The most obvious example is in contract: if a solicitor contracts with a client to carry out the advocacy in a trial personally, that solicitor has a Hohfeldian duty to the client to so act and the client has a corresponding Hohfeldian claim right that the solicitor so act.

The solicitor's right of audience could also be envisaged as a Hohfeldian claim right against a court that has a correlative duty to hear the advocate. Here the nature of the right under the Act is illustrated by the comparison above between the McKenzie Friend whose right is conferred by the court itself, and a lawyer who can only be sanctioned by the court after or during the event, by a wasted costs order or reporting to the regulator. As Mayson points out, such ATE redress is unlikely to extend to actually overturning the result of the case.Footnote 82 That a judge can report is assumed, and the SRA promises to reinforce this. That process is, however, far less explicit in this jurisdiction than, for example, the express DTE power of the European Court of Human Rights to expel an advocate.Footnote 83

The claim right/duty analysis vis-à-vis the court seems to work rather better in an individual case such as that of the McKenzie Friend, or at the moment when the advocate first stands up before the judge. A different Hohfeldian analysis seems more consistent with the overall position of the solicitor conferred with a right that he or she may exercise a Hohfeldian power never to exercise. This is to treat the solicitor as having a Hohfeldian privilege to appear in court, and no necessary duty to the court, regulator or anyone else either to do so or not to do so. Where such a duty does arise, it does so through a contractual claim right conferred on a client by the retainer with the solicitor. In the normal course of events, courts, regulators and clients cannot compel the solicitor to appear (the correlative no claim of the Hohfeldian privilege). The incompetent advocate, provided presumably they are aware they are incompetent, need not do so.

Whether a right of audience is a Hohfeldian right as against the court, a Hohfeldian duty to an individual client or a privilege which a solicitor cannot be compelled to exercise, the regulator has, at least, a Hohfeldian power to deprive someone of the right, or place conditions on it as a function of its ATE regulation.Footnote 84 The unethical or incompetent advocate therefore has a corresponding liability to have the primary claim-right or privilege altered. Such an alteration might be a limitation by conditions placed on a practising certificate or complete removal by suspension or striking off. The effect of the SRA's DTE link between the competence statement and the obligation to act only if competent in its ethical code renders the advocate liable to ATE sanction. It is, however, a separate obligation: the right to act appears in one place and the obligation to act only if competent elsewhere.

The regulator, in its turn, owes a duty to the umbrella regulator, the LSB, to police its regulated community and the LSB has a corresponding claim right that it should do so.

Clearly, the regulator is enabled to act on evidence of ATE lack of competence (as is the client and the employer in claims in contract and tort). Unlike the individual solicitor, however, Hohfeld is not interested in the grounds for exercise of the power, or the likelihood of its being exercised (which has the potential for any deterrent effect). The regulator's Hohfeldian power to sanction is enshrined in the professional regulations: the regulator has a claim right, on behalf of the LSB and society in general, that the solicitor act competently and the solicitor has a duty to the regulator to do so.

There is nothing in Hohfeld's analysis per se that demands reciprocity between solicitor and regulator. That is, that the regulator ensure that the solicitor has BTE training and assessment in advocacy to a level that equips them, in principle, to avoid ATE sanction from the regulator. There is, however, likely to be such a claim between solicitor and employer (where there is one). It is assumed that the regulator's objective is not only ATE sanction, but also the pre-emptive prevention of incompetent advocacy in the first place. Achieving this, in the absence of mandated BTE education or other assurance of competence, in this cat's cradle of intersecting rights and duties, depends on the pull of the DTE duty to the regulator and fear of ATE regulatory accountability effectively holding in check the push of the claim right to perform vis-à-vis the client and the court.

One way of de-emphasising the entitlement to act that has then to be restrained by other means, would be to reconfigure it as a Hohfeldian privilege. Semantically this carries implications about decision making and responsible action, albeit, as we shall see, without the emphasis that Waldron explicitly places on these issues. It more closely places the BTE responsibility for competence not on mandatory BTE education, but on the individual solicitor and his or her employer in the way that the SRA now envisages. In terms of stakeholders, the privilege/no claim analysis is also cleaner and therefore more comprehensible than the tripartite analysis involved in treating trial advocacy as a claim right and separating rights, competence and regulatory accountability into distinct obligations. As a potential replacement term for ‘rights of audience’, ‘privilege of audience’ aligns semantically with the existing lawyer/client privilege, but, as the two are not coterminous, could be confusing. It does not do enough, however, to inhibit incompetent performance in the absence of BTE education and assessment.

If a Hohfeldian analysis serves to emphasise heterogeneity and the divergence that is a characteristic of the modern regulatory landscape, Waldron, in his concept of ‘responsibility rights’Footnote 85 is interested in homogeneity and convergence. To this extent his responsibility right overlaps with Hohfeld's privilege. Waldron takes the notion of privilege further, however, in his attention to how and why the privilege is exercised: ‘the responsibility aspect is a way of informing and conditioning the individual possession and exercise of the right’.Footnote 86 This accommodates competence as well as rights and accountability in a way that Hohfeld does not. Indeed, Waldron's model prioritises responsibility for competence over entitlement to perform. For Waldron:

… the claim that you have a right to do something is no answer to a criticism of the way you exercise your right. Or put it the other way round, having a right in and of itself does not give you a reason, let alone a moral reason, for exercising the right in any particular way.Footnote 87

Waldron does not claim that all rights are responsibility rights and, indeed, there are clearly rights for which a ‘price’ of responsible behaviour by the actor is inappropriate. Franke, with a focus on human dignity, sees the establishment of a normative ‘responsibility’, as adjudged by others, as a precursor to the grant of the right, and a price which may in some circumstances be ‘too high to be paid’.Footnote 88 In the context of trial advocacy, when the risk for individual litigants and society is taken into account, this critique seems less compelling.

The SRA has, however, by squarely placing responsibility for competent practice on the individual solicitor and his or her employer, clearly exacted a price for that responsibility in the shape of ATE regulatory sanction. Waldron claims that his model transcends ‘crude obligation-analysis’ (of, we infer, the Hohfeldian kind) to relate freedom with authority and to connect rights with ‘socially important functions and with dignity’. Indeed, the concept of responsibility rights seems to be particularly well aligned with professional privileges (‘dignities’) and licences such as the right to conduct trials. For Waldron, a responsibility right involves:

(1) the designation of an important task, (2) the privileging of someone as the person to perform the task, making the decisions which the task requires (3) doing so in view of the particular interest that they have in the matter, and (4) the protection of their decision-making-sphere pursuant to this responsibility against interference by others and even by the state (except in extreme cases).Footnote 89

Jones Merritt and Merritt have argued that the right to practise law is itself, inherently, a responsibility right.Footnote 90 They do so, however, in the context of the unified, essentially self-regulating US legal profession, where lawyers benefit from some immunity from suit and have a particular role in the upholding of the constitution to which they are entitled by virtue of their ‘training and inclinations’.Footnote 91 In this context, the lawyer monopoly over the ‘practice of law’ operates to ‘shiel[d] individual lawyers from direct competition [and] prevent[s] innovators from challenging the practices of the profession as a whole’.Footnote 92 The key to their claim to the responsibility right lies in their analysis of Waldron's criterion 3. If lawyers fail to promote access to justice, Jones Merritt and Merritt argue, the claim to a responsibility right fails. Or Waldron's fourth criterion applies and the state is entitled to ATE intervention. In that case, their solution is to withdraw criterion 2 by imposing the kind of deregulation and competition that is, in England and Wales, enshrined in the Act.Footnote 93 It seems likely, therefore, that Jones Merritt and Merritt would conclude that the practice of law in England and Wales does not satisfy Waldron's criteria. However, even in its own context, their approach seems rather too broad. Indeed, Bix suggests that Waldron's model, combining what Hohfeld termed a ‘molecular’ bundle of rights and duties, is more accurately a depiction of a ‘role’ rather than a species of right.Footnote 94 A ‘role’ is clearly capable of embodying both rights and responsibilities and in the US context, regulation by activity and by title are coterminous. In the context of the Act's distinction between regulation by title and by activity, roles are, it is suggested, better envisaged as being closer to titles.

In the petri dish that is the Anglo-Welsh deregulated context, it is, however, feasible to treat trial advocacy as a homogenous responsibility right, shared across multiple professions with heterogenous regulatory structures. Its importance (criterion 1) is signalled by its status as a reserved activity under the Act, and the privileging (criterion 2) occurs in the statutory designation of authorised and exempt persons entitled to perform it. As we have seen, regulators and others are already entitled to impose ATE sanctions and to withdraw or limit licensure in those cases where complaint is warranted, although perhaps with greater readiness to intervene than Waldron envisages (criterion 4). Indeed, the SRA's new model will rely on criterion 4 as its sole means of control of lower court trial advocacy. To be effective, therefore, it must operate either as a deterrent fear of regulatory accountability, or as an ATE sanction at a time when, by definition, the damage to the individual litigant has already been done. Waldron clearly expects the operation of the three prior criteria, particularly perhaps criterion 3, to render criterion 4 a last resort. Decisions made by advocates in trial to, for example, call or examine a particular witness or not, or to pursue a particular line of argument, are, problematic to second guess by regulators.Footnote 95 Waldron acknowledges this difficulty when he articulates criterion 4 as a freedom from ATE sanction in most cases, rather than a pejorative liability to it.

Criterion 3, which seems to have troubled Jones Merritt and Merritt, is the key in the context of the fight to acquire, and then to maintain, solicitors’ claims to rights of audience. A solicitor conducting a county court or magistrates’ court trial may have many different kinds of ‘interest’ in so doing, including those mentioned in paragraph 22 of the consultation paper: remuneration; personal aggrandisement; skill enhancement; promotion of access to justice; commitment to a particular client or case or asserting a position in the market against other professions. The interests of both access to justice and competition are, of course, legitimated by the Act. One of the concerns about McKenzie Friends, particularly in family law, is that they are driven by activism rather than altruism. Some interests are clearly more morally valid than others, but any or all could be in play in addition to the interest based on pre-emptively established claim to special competence that Waldron prioritises. Indeed, in the SRA's new regime, in the absence of required BTE training, assessment or meaningful learning opportunities in the workplace, there will be, in most cases, nothing to support any such pre-emptive claim in witness examination. There is very little even at present to support any such inference but the omission of the skill from the SQE makes the point quite stark. The interest in competing in the market seems to have won the day, even though, compared to the other professions, this plan in fact weakens solicitors’ competitive position.

The responsibility right concept facilitates the debate about the qualitative merits of competing interests in a way that the Hohfeldian model does not. The Hohfeldian model is a tension field, in which rights and accountability are distinct, owed to different stakeholders and assumed to hold each other in check, and interest in and competence to act are of, if anything, subsidiary concerns. If we see a right of audience as a (mere) Hohfeldian claim-right or, more accurately, as a privilege, then much depends on the individual's fear of the regulator's ATE powers. This fear is contingent, as are all claims of deterrence, on a belief in discovery, of prosecution and of application of sanctions. The DTE reference to competence in the code of conduct bears the weight, of course, of other areas of legal practice, such as trade mark or welfare benefits law, that do not appear in the SQE, but these are not components of the statement of solicitor competence, nor are they reserved activities specially marked out by the Act.

The SRA's 2019 regulations, as we have seen, shift the weight of responsibility for competence in lower court trial advocacy to individuals,Footnote 96 supervisors and managersFootnote 97 and firms.Footnote 98 Although competence and the right of audience are located in different parts of the rules, this model is in principle closer to Waldron's model than it is to Hohfeld's. It is, however, unilaterally imposed, and the shift in the BTE and ATE balance may not be sufficiently explicit to the profession. The profession will, shortly, be able neither to treat responsibility for BTE acquisition of competence as delegated to the regulator (which has disclaimed it) or infer it from BTE structures that may in fact never have been capable of robustly assuring it. The SRA's shift entitles – in fact obliges – the profession to take hold of the responsibility to perform competently, in the interests not only of effective market competition, but inherent professional dignity.Footnote 99 It can do so reluctantly, or with enthusiasm. Treating trial advocacy as a responsibility right fosters this as it entails consciously embracing criterion 3 in the case of individual lawyers, firms or affinity groups, developing new ways to model and measure competence, interrogating different theories of practice, and the motivations for action rather than permission to act in individual cases and as time passes, rather than once and for all at qualification.Footnote 100 It allows the profession itself to drive the question of competence pro-actively, rather than relying on deterrence or ATE sanction that is too late to prevent the damage. It allows the profession explicitly to determine and articulate its special interest (criterion 3) in the competitive market where others rely on BTE assessment. Waldron, it should be remembered, envisaged criterion 4, the ultimate sanction of removal of the right, as an interference with dignity to be exercised sparingly. This would involve the SRA, rather more than it appears to do at present, exercising its powers to place targeted conditions on individuals’ licences preventing them from conducting trial advocacy, either at all, or until remedial training has been undergone.Footnote 101 Complete suspension from practice, or striking off, might then be reserved for the most egregious cases, where ethics, more than competence, is at issue. The challenge for the solicitors’ profession will be to act in such a way that the SRA can do so.

Conclusion

The divergence of the SRA from the national norm, and its potential implications in the competitive marketplace, have been the trigger for the discussion in this paper. That discussion, however, has led to conclusions that have relevance for all advocacy, and perhaps especially for those jurisdictions where acquisition and maintenance of competence is left to the individual lawyer, subject to ATE regulatory sanction.

There is, I suggest, an urgent need to decouple trial advocacy from any sense of entitlement conferred by the use of the word ‘right’. None of the other reserved activities are described in this language in the Act. None should be. If we re-envisage rights of audience as responsibility rights we can cut through the Hohfeldian cats’ cradle of intersecting rights, duties and powers pulling in different directions, with different degrees of force and vested in different stakeholders. We can focus on and evaluate the relative force of the different drivers, and the moral and ethical validity of interests, and continued interests, in performing effectively, rather than delineate their relationships.

If, from 2021, nothing can be assumed from the BTE environment, then as is clear from the SRA 2019 regulations, it is for the solicitors’ profession to take on that responsibility, and that can be done most robustly by the profession embracing Waldron's holistic model where rights (criteria 1 and 2), competence (criterion 3) and regulatory accountability (criterion 4) blend. In the new regime this will be critical if solicitors are to retain any credible claim to compete in the field of witness examination: in Waldronian terms, to have a justified special ‘interest’ in so doing. As a model that makes it clear that society demands a price for the privilege, particularly in our deregulated, competitive marketplace, it is also, I suggest, an approach that should apply to all advocates, including the McKenzie Friend. Beyond England and Wales, where the term ‘rights of audience’ may not be used in quite the same way, this analysis provides a way of thinking about the distinctive task of advocacy, with, as indicated at the beginning of this paper, its implications for livelihood, family, liberty and sometimes life itself, that has the potential to inhibit incompetence and reinforce the role of the lawyer as a dignified actor for social good.