The balance of power between boards of directors and shareholders has long been a central issue in corporate governance. In the past decade, policymakers and scholars have advocated for shareholder empowerment.Footnote 1 In April 2017, the European Council amended the Shareholders’ Rights Directive (2007/36/EC) of 11 July 2007 to enhance corporate transparency, facilitate the exercise of shareholder rights, and encourage long-term engagement by shareholders.Footnote 2 Changes in US public companies regarding pay for performance, declassified boards, and proxy access also exemplify the trend towards shareholder empowerment.Footnote 3 The shareholder empowerment movement rests on the assumption that when outside shareholders are empowered by strong shareholder rights, they will exercise their rights to constrain the power of incumbent managers or controlling shareholders, and thus improve corporate governance.

The question, however, is whether shareholders who face oppression or unfair treatment from managers or controlling shareholders actually exercise their rights. In theory, investors could influence firms’ governance choices by ‘voting with their feet’ by ‘exiting’ the company, or by demanding changes by using their ‘voice’.Footnote 4 Shareholders, however, seldom exercise these rights because shareholders, at least in the US context, are generally passive. Shareholders either do not vote, in the case of individuals, or vote for incumbents’ proposals, in the case of institutions. Very few shareholders actively exercise their rights to change corporate practices or challenge board decisions.Footnote 5 However, over the past decade, US hedge funds have been actively demanding changes in US public companies, which has altered the corporate governance landscape in the US.Footnote 6 Following the UK’s adoption of the Stewardship Code in 2010, policymakers around the world have also adopted codes that encourage the active involvement of shareholders as a means of enhancing corporate governance.Footnote 7

Existing studies on hedge fund activism generally focus on US public companies, which account for over 65 per cent of worldwide hedge fund activism.Footnote 8 Most US public companies are widely held, and conventional wisdom holds that shareholder activism is effective only in firms with dispersed ownership structures.Footnote 9 Activists present no threat to controlled companies because they have no prospect of replacing incumbent corporate boards that are in the hands of controlling shareholders.Footnote 10 That does not mean, however, that activism cannot work in firms with controlling shareholders, particularly when controlling shareholders do not own a majority of shares but control the firm through other means, such as pyramidal structures, cross-shareholding, or friendly outside investors. The existing literature has shown that activism can work even in firms with controlling shareholders.Footnote 11 However, it is not clear whether and how the law and its mechanisms influence shareholder activism in controlled firms.

Traditionally – with the exception of Japan – Asia has had very few instances of shareholder activism.Footnote 12 Activist campaigns in Asia, however, have increased steadily in recent years. The number of Asian companies facing public demands from activists grew from thirty-four in 2013 to seventy-eight in 2016. From 2013 to mid-2017, a total of 257 Asian companies faced public demands by activists. Compared to the 1,936 public demands in the US during the same period, activism is not nearly as frequent in Asia.Footnote 13 Outside of Japan, Hong Kong is the Asian jurisdiction where most public activist demands have taken place in recent years.Footnote 14 Since the ownership structure of most Japanese listed companies is dispersed, it is understandable that many activist demands and hostile takeover attempts occurred in Japan, but to little avail.Footnote 15 However, in Hong Kong, like in most other Asian jurisdictions, the majority of large listed companies are controlled by families or by the state. This arguably makes Hong Kong an ideal subject of study for shareholder activism in controlled companies, which may yield valuable insights that may also apply to other Asian jurisdictions except Japan. As one of the most developed capital markets in the world, the Hong Kong government has made investor protection and corporate governance of listed companies a priority in the past decades.Footnote 16 The increase of shareholder activism in Hong Kong has been stimulated by the promulgation of the Principles of Responsible Ownership (Principles) in Hong Kong in March 2016, which was modelled on the UK Stewardship Code. The Principles encourage investors to engage actively with companies about their expectations and voting policies.Footnote 17 These institutional conditions make Hong Kong a particularly suitable jurisdiction for the study of shareholder activism in controlled companies.

However, hedge fund activism is not without controversy. Critics have claimed that hedge fund interventions tend to be myopic and are likely to have a detrimental effect on the long-term interests of companies.Footnote 18 However, this claim has been rebutted by a recent empirical study showing that there was no negative effect on the operating performance and stock returns of US target firms during the five-year period following activists’ interventions.Footnote 19 The only empirical paper about activism in Hong Kong tested the stock returns of target firms from 2003 to 2015, and also found that activism increases firm value, both around the announcement of activists’ investments and in the following year.Footnote 20 Furthermore, concerns over shareholder activism in the United States do not necessarily apply to Hong Kong or other Asian jurisdictions, because the current level of activism is quite low in these jurisdictions, and the ownership structure of listed firms in these jurisdictions is vastly different from that of US firms. Studies have shown that when transplanted to Asia, American mechanisms for shareholder power such as derivative actions, independent directors, and shareholder activism have often transformed into localized adaptations with unexpected results.Footnote 21 Asia generally lacks effective external governance mechanisms that constrain controlling shareholders, including an active market for corporate control, effective shareholder litigation, and class action regimes.Footnote 22 Given the common presence of controlling shareholders and the relatively low levels of activism in Hong Kong, it might be worthwhile to explore whether shareholder activism can be an effective external governance mechanism, rather than worry about its disadvantages. Regardless of the debate over the benefits and drawbacks of hedge fund activism, assessing the effectiveness of hedge fund activism is beyond the scope of this article.Footnote 23 Unlike the existing literature, this article confines its scope to examining the role of law and legal remedies in activism in controlled firms.

To investigate how legal mechanisms influence activists’ strategy planning and outcome in campaigns against controlled firms, this article first analyzes the theoretical effectiveness of different legal mechanisms in the context of activism against controlled firms. The analysis shows that seeking board representation is a weaker activist strategy than either commencing litigation or exercising minority veto rights, given the institutional setting in Hong Kong. Next, to empirically investigate how various legal mechanisms work in practice, the author compiled a list of activists’ shareholdings in controlled firms from 2003 to 2017, as well as hand-collected data on the legal strategies employed by hedge funds, institutional shareholders, and proxy advisors against firms with controlling shareholders. Based on the Hong Kong data, I find that cases using formal legal mechanisms appear to have had a higher success rate, and that among the various legal tools available, minority veto rights are the most commonly used and the most effective tool for activists to leverage their position in controlled firms. Furthermore, there is evidence that the availability of legal remedies and the shareholding level of controlling shareholders are both factors that influence the strategies employed by activists. Two-thirds of activist incidents against controlled firms in Hong Kong are related to corporate governance disputes in which activists, as minority shareholders, could have exercised certain rights under the law and exerted greater influence on firms. However, when dealing with controlling shareholders who control a majority of shares, activists have tended not to make their demands public or exercise their legal rights.

This article contributes to the existing scholarship on shareholder activism in two major ways. First, of the prior studies concerning the possibility of activism in controlled firms, very few study the Asian context,Footnote 24 even though the focus of hedge funds has gradually shifted to Europe and Asia in recent years.Footnote 25 In the foreseeable future, battles between activists and controlling shareholders will only become more frequent. Given that most Asian listed companies have controlling shareholders, the findings of this article can be valuable to other Asian jurisdictions as well. Second, most prior studies focus on the financial impact of activism on target firms or ownership patterns, like those relating to ‘wolf pack’ tactics, while neglecting the role of legal institutions in the shareholder engagement and negotiation process.Footnote 26 This study identifies the importance of legal institutions – in particular, minority veto rights – in shareholder activism against controlled firms.

This article is structured as follows. Part II explains the reasons for the historical lack of shareholder activism in Hong Kong and the recent change in this paradigm. Part III maps out the different legal mechanisms available to activists and includes a discussion of the effectiveness of each mechanism. Part IV presents empirical findings on the effectiveness of different legal mechanisms in practice, based on hand-collected data on Hong Kong-listed companies. Part V concludes.

I. THE CHANGING PARADIGM OF SHAREHOLDER ACTIVISM IN HONG KONG

Shareholder activism has been rare in Asia. From 2000 to 2010, only around 12 percent of activist engagements worldwide took place in Asia, compared to 22 per cent in Europe and 66 per cent in North America.Footnote 27 The reasons for the scarcity of activism in Asia include the propensity for listed companies to have controlling shareholders, the prevalence of cross-shareholdings, the passivity of retail and institutional investors, and cultures that are less litigious and confrontational.Footnote 28 These reasons all apply in Hong Kong, where most listed companies are either family- or state-controlled, leaving minority shareholders with almost no ability to achieve anything at general meetings.Footnote 29 The usual means for enhancing control in Hong Kong is through a pyramidal structure or cross-shareholding. Claessens, Djankov and Lang found that 25.1 per cent of the controlling shareholders of Hong Kong’s largest listed firms enhance their corporate control through pyramidal structures, and 9.3 per cent do so through cross-shareholdings.Footnote 30 As a result, retail shareholders support family controllers rather than the business when investing in a company, and vote with their feet to avoid poor corporate governance.Footnote 31

In the past, hedge funds were not active in Asia simply because there was little chance to profit, given the prevalence of concentrated ownership structures in the region’s public companies. Unlike hedge funds, institutional shareholders like index funds and mutual funds have been investing in Asian companies for some time. However, institutional investors were generally passive investors that did not actively engage in business decisions. Even when they exercised their voting rights, they typically followed the recommendations of proxy advisors.Footnote 32 Institutional investors were passive for several reasons. First, institutional investors were only a small part of the investor base. In the past, Western institutional investors tended to regard the small Asian portion of their portfolios as exotic, the metaphorical ‘spice from the East’.Footnote 33 Without a sufficient stake in the company, it would be very hard for institutional investors to make their voices heard on corporate policies.Footnote 34 Second, institutional investors lack the incentives to actively monitor their portfolio firms because the benefits of those efforts would be shared by all investors, including their competitors.Footnote 35 Thus, institutional investors are in general ‘rationally reticent’ towards improving the corporate governance of their portfolio firms.Footnote 36

That is not to say that shareholder activism has never taken place in Hong Kong; rather, it usually takes place behind closed doors. Anecdotal evidence suggests that there have been hundreds of behind-the-scenes activist interventions over the past twelve years in Hong Kong.Footnote 37 There are many reasons for this state of affairs. First, there is the longstanding Asian cultural aversion to public confrontation.Footnote 38 In addition, unlike their American counterparts who benefit from contingent fees and class actions, retail and institutional shareholders can rarely afford to pursue legal action to enforce their rights in Hong Kong.Footnote 39 In recent years, the Hong Kong government adopted rules that support shareholder activism, and controlling shareholders and boards of directors are changing their attitudes towards activists as well. On 2 March 2015, the Securities and Futures Commission (SFC) issued the Consultation Paper on the Principles of Responsible Ownership,Footnote 40 which were eventually adopted on 7 March 2016.Footnote 41 These principles are intended to encourage institutional shareholder activism, which the SFC believes ‘will improve the governance and performance of investee companies that will, in the long term, enhance the efficient operation of our capital markets and contribute towards an increase in the confidence of the Hong Kong financial market as a whole’.Footnote 42 Following developments in foreign jurisdictions such as the UK, which released a similar Stewardship Code in 2010, the SFC is expected to continue to push for changes in this regard.Footnote 43

These reforms provide institutional shareholders with the tools to push back against company management.Footnote 44 Activist investors are also becoming more insistent in seeking out better returns in Asia amid ultra-low interest rates and sluggish global growth.Footnote 45 This change in attitude started with BlackRock’s public campaign against G-Resources in Hong Kong in February 2016, the first significant activist campaign launched by a large institutional investor.Footnote 46 BlackRock, one of the largest asset management groups in the world, has been increasing its investments in the Asia-Pacific region, and it expects to actively engage with more Hong Kong companies and exercise its voting rights at every shareholders’ meeting in the coming years.Footnote 47 This move has roiled the waters in Hong Kong’s capital market and will likely enhance both transparency and corporate governance in Hong Kong-listed companies.

Controlling shareholders remain the greatest obstacle to shareholder activism in Hong Kong. Most family controllers in Asia are generally hostile to outsiders.Footnote 48 There are signs of change, however, as companies are seeing the virtues of engaging with their key stakeholders, and increasingly carrying out crisis training and scenario planning to prepare for greater investor scrutiny.Footnote 49 In addition, there is likely to be a shift away from a family-driven culture, as the founders are starting to sell their interests for succession, diversification, or other purposes; their companies will find it beneficial to engage with shareholders in the furtherance of transactions that require independent shareholder approval.Footnote 50

II. ACTIVIST STRATEGIES AGAINST CONTROLLED FIRMS

A. Forms of Engagement

1. Private engagement

Shareholder activists usually first communicate with the target firm through informal and private engagements.Footnote 51 Public communications or interventions are typically considered only after the failure of private engagement because of the costs and risks involved in public intervention.Footnote 52 Public campaigns represent only a small percentage of the activism that reaches the public eye. In practice, private engagement is a tactic more commonly used by fund managers and institutional investors.Footnote 53 Private engagement refers to the approach adopted by investors, usually those who focus on long-term investments, to communicate with the management of the firm in a constructive way to improve firm performance or corporate governance.Footnote 54 Through the engagement process, investors become more informed about corporate strategies, and managers gain a better understanding of the investors’ concerns and agendas.Footnote 55 The goal of private engagement is to inform investors about voting decisions, and to bring about changes which benefit both the firm and its investors. Over time, private engagement can also build trust between investors and a firm, and facilitate effective ongoing dialogue.Footnote 56

Some asset management firms have made shareholder engagement part of their regular routine. For example, BlackRock has an investment stewardship team dedicated to shareholder engagement and communication. BlackRock also publishes corporate governance and proxy voting guidelines for major jurisdictions to inform companies of their expectations and voting policies.Footnote 57 With the increasingly routine nature of shareholder activism, companies now also devote internal resources and even involve external advisors to manage shareholder engagement efforts.Footnote 58 From July 2016 to June 2017, BlackRock conducted 1,274 private engagement meetings worldwide, of which 52.9 per cent took place in the Americas and the UK, and only 9.26 per cent took place in the Asia-Pacific region (excluding Japan).Footnote 59

For shareholder activists, the major difference between public companies in the Asia-Pacific region and those in the US and the UK is ownership structure. The ownership of most Asian firms is concentrated, while ownership of US and UK firms is usually highly dispersed. If a target firm is widely held, activists would be likely to engage either management or the board. If, however, the target is a controlled firm, activists will need to communicate with the controlling shareholder. The presence of a controlling shareholder makes it harder for activists to exert leverage using a takeover threat to press a firm to make changes. The battle between activists and controlling shareholders depends on two factors: the percentage of shares held by activists, and the jurisdiction’s legal regime for minority shareholder protection.

The greater the activist’s shareholding in a company, the more likely it is that that activist’s requests will be heard in a private engagement. Even though it is practically impossible for an activist to launch a successful takeover in a controlled firm, the activist can seek minority representation on the board. An activist who holds a substantial stake may lobby for the appointment of a minority director to represent minority interests, which would put pressure on the controlling shareholder, who generally dislikes an ‘outsider’ on the board.Footnote 60 Such nominee directors cannot outvote controlling shareholders on the board, but their views are likely to influence decision-making and sway other non-executive directors.Footnote 61

Another factor in private engagement is the legal protection of minority shareholders. Greater legal protection grants greater bargaining power to activists engaging with controlling shareholders; consequently, it is more likely that such engagements will be successful. The law often grants minority shareholders veto rights in conflict-of-interest transactions (see Part II.B.4). This article shows that minority legal protection, rather than ownership level, has a greater influence on the outcomes of activist engagement with controlled firms.

2. Public intervention

If private engagement is not effective, activists may escalate by making their interventions public. Almost all public interventions by activists involve public announcements about their demands. An open letter released to the media can put pressure on controlling shareholders. Public criticism not only causes share prices to fluctuate, but also harms controlling shareholders’ reputations, especially if the activists’ demands involve corporate governance issues implicating potential expropriation of minority shareholders’ interests. An open letter is the most cost-effective way of attracting public investors’ attention and increasing the success rate of activist campaigns. Without other bargaining chips, such as a threat to veto related party transactions (RPTs), activists’ demands are likely to be ignored by controllers. In the US, the success rate of an ‘open letter only’ campaign is much lower than that of other interventions through legal mechanisms.Footnote 62 Similar findings apply to Hong Kong; whenever an activist such as H Partners Management, QVT Financial, or BlackRock chose to only deploy an ‘open letter’ strategy, the activist’s campaign failed (see Appendix).

B. Formal Legal Mechanisms

Private engagement and public intervention illustrate different modes of communication by activists. What is really at stake, however, is their bargaining power. Previous literature has revealed that ownership and voting power are crucial to the success of activist initiatives.Footnote 63 Ownership might be important to widely held firms because high levels of outside shareholding and the possibility of ‘wolf pack’ tacticsFootnote 64 pose a takeover threat to target firms. If the target firm is a controlled firm, it is unlikely that activists will, or can even hold enough shares to threaten the power of controlling shareholders. In this situation, legal mechanisms that offer protection to minority shareholders could be decisive in activists’ campaigns against controlling shareholders. This part provides a survey of legal mechanisms available to activists, and a discussion of their effectiveness in engagements with controlled firms.

1. Board representation

In most controlled firms, shareholder activists cannot win a full or even a majority slate because of the presence of controlling shareholders.Footnote 65 This is even more true in a dual-class share company or a company with other control-enhancing mechanisms that are popular in Asia, such as cross-shareholding or pyramidal structures. Although minority board representation does not impair the ability of controlling shareholders to determine business strategy or invoke a change of control, the mere presence of minority nominee directors could change board dynamics and thus have an impact on decision making.Footnote 66 Even if winning a proxy fight is unlikely, a contested slate proposed by activists may damage controlling shareholders’ reputations and put pressure on them to respond to activist proposals.Footnote 67

A few factors determine the success of such tactics. The first is whether the company has reserved board seats for minority nominations. In the 1980s, most US dual-class firms granted holders of shares with inferior voting power the right to elect a minority (usually 25 per cent) of board seats.Footnote 68 Studies show that activists in the US frequently seek the nomination of their own directors to the board, even in a controlled firm. An empirical study on hedge fund activism in US-controlled firms from 2005 to 2014 found that 56 per cent of engagements involved the nomination of directors representing minority shareholders.Footnote 69

The second factor influencing the success of activists in terms of board representation is the rules on director appointments. If the firm adopts cumulative rather than majority voting, it is more likely that shareholder activists will successfully elect their nominees to the board, making the short (minority) slate strategy a more credible threat to the controlling shareholder.Footnote 70 However, very few Asian jurisdictions have made cumulative voting mandatory in public companies.Footnote 71 In the absence of mandatory rules, it is reasonable to expect that only a few controlled firms will voluntarily adopt a cumulative voting rule that disadvantages the controlling shareholder in director elections.

The third factor is board tenure. If a staggered board is used, only a fraction (usually one-third) of the directors are up for election every year. Even in a widely held firm, a staggered board can substantially delay a potential takeover, and present an obstacle to shareholder activists who seek a controlling (or majority) slate.Footnote 72 Even though a takeover threat is not of much concern to a controlled firm, a staggered board can also disadvantage activists supporting a minority slate in a controlled firm, if the firm adopts cumulative voting. Under a cumulative voting regime with a staggered board, activists would need to garner a greater percentage of votes to support one seat when the number of seats put up for election decreases.Footnote 73

2. Court proceedings

As it is much more difficult to gain board representation in a controlled firm than in a widely held firm, it is usually more effective for shareholder activists to resort to court proceedings as a lever to pressure controlling shareholders. The first tool that activists can use is the exercise of shareholder rights granted under company law or the articles of association. While litigation is costly and time-consuming, seeking court orders to enforce shareholder rights or obtain injunctions is faster and easier to achieve. For example, under Section 740 of the Hong Kong Companies Ordinance 2014 (Companies Ordinance),Footnote 74 shareholders can apply for a court order to inspect company records or documents. Such rights can be exercised by activists to challenge a specific transaction if a firm does not disclose sufficient information about that transaction to the public, although the exercise of these rights must satisfy the good faith and proper purpose test.Footnote 75 The Companies Ordinance requires plaintiff shareholders to hold at least 2.5 per cent of the voting rights, or comprise a group of at least five shareholders in order to apply for an inspection order.Footnote 76 A court inspection order is a widely available remedy for activists because the law imposes a relatively low standing threshold.

The timing of inspection orders, however, could be an issue. Without a specialized business court, a transaction may have been completed by the time a court grants an inspection order. The intervention of Elliott Management (Elliott) against the Bank of East Asia (BEA)’s private placement arrangement is an example. On 5 September 2014, BEA announced a proposed placement of shares to a substantial shareholder, Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation, which would support the Li family’s control over management.Footnote 77 Concerned about the lack of proper commercial basis for the placement, the entrenchment of the position of the Li family directors, and the lack of adequacy and thoroughness of the decision-making process by the directors outside the Li family, US hedge fund activist Elliott applied for an inspection order on 16 January 2015 to request disclosure of documents relating to the private placement at issue.Footnote 78 Shortly after the action, BEA held a board meeting and approved the placement on 12 February 2015, completing the subscription on 27 March 2015. The court did not issue its order until 5 June 2015.Footnote 79 Elliott, of course, failed to stop the transaction and was thus unsuccessful in this intervention.

A court inspection order could raise public awareness of the subject transaction and exert public pressure on controlling shareholders. It cannot, however, stop the transaction. It is thus not as effective as an ‘interim injunction’, which restrains controlling shareholders from engaging in transactions that would harm shareholders’ interests, pending litigation. Under Sections 728–730 of the Companies Ordinance, any shareholder can apply for a statutory injunction if controlling shareholders or any other persons engage in conduct contravening the Companies Ordinance, including breach of fiduciary duties by directors or breach of the articles of association. This is a broad power that activists can exercise to challenge unfavourable transactions; indeed, it proved effective in the private placement case between Passport Special Opportunities Master Fund LP (Passport) and eSun Holdings Ltd (eSun).

Passport, a US hedge fund and major shareholder holding roughly 28 per cent of eSun’s issued shares, was unhappy about a private placement transaction with Chung Name Securities Ltd authorized by eSun’s board on 10 December 2008.Footnote 80 After private engagement and communications with the board failed, Passport applied for an ex parte injunction to restrain eSun from proceeding with the placement on 22 December 2008 – shortly before the scheduled completion date.Footnote 81 Passport alleged that eSun’s directors were acting with an improper purpose when entering into the placement agreement, and the injunction was granted by the court, postponing the placement.Footnote 82 Unlike the BEA case, in which Elliott applied only for an inspection order and ultimately failed to stop the transaction, Passport utilized a more effective legal tool – the injunction – to successfully postpone the proposed transaction and eventually force eSun to terminate the agreement.Footnote 83 This demonstrates that activist minority shareholders can use court orders to stop controlling shareholders from engaging in the impugned conduct pending the court’s final verdict.

3. Litigation

An activist can also exert pressure on a controlling shareholder by filing a lawsuit. This is the most time-consuming and expensive approach among all means of legal leverage. Activists must expend a substantial amount of time, effort, and money should they choose to sue the target firm. In the US, only 5 per cent of activist engagements against controlled firms involve lawsuits.Footnote 84 This low percentage is reasonable because litigation costs in the US are relatively high. Litigation can, however, effectively restrain controlling shareholders and prevent them from taking unilateral actions against activists.Footnote 85 Furthermore, litigation creates public pressure on controlling shareholders because the litigation itself usually implies that a controlling shareholder of the firm has expropriated minority shareholders or breached director’s fiduciary duties. This negative public image could damage a controlling shareholder’s reputation as a decent corporate manager and a responsible controlling shareholder.Footnote 86 In particular, when the controller is the founder of a firm or belongs to a founding family, the controller will be especially concerned about reputational damage to the firm.Footnote 87 Employing litigation strategically could therefore be more effective with family controllers.Footnote 88

In Hong Kong, most large public companies are controlled by founding families.Footnote 89 Minority shareholders can bring derivative actions or seek relief under the unfair prejudice remedy where the company or its controllers have engaged in oppressive behaviour against them.Footnote 90 Even though private enforcement is rare in Hong Kong, shareholder litigation was effective in the Passport case.Footnote 91 In addition to the interlocutory injunction, Passport also filed a petition under the unfair prejudice remedy, seeking injunctive and declaratory relief to prevent completion of the proposed placement and to declare the transaction invalid.Footnote 92 Soon after the interlocutory injunction was granted pursuant to the petition for unfair prejudice, eSun terminated the placement agreement.Footnote 93 Passport thus effectively forced eSun to terminate the placement by resorting to formal legal recourse. In this case, shareholder litigation played only a supplementary role by justifying the interlocutory injunction order, which stopped the transaction immediately. The court eventually dismissed Passport’s claims for relief after two and a half years, and decided not to set aside or void the placement agreement on grounds of protecting third-party placees.Footnote 94 Nevertheless, Passport still succeeded in terminating the placement.

Elliot also sought formal legal recourse in an attempt to intervene in a private placement transaction by BEA, but its efforts were in vain. Elliot applied not for an injunction but an inspection order, which obviously would not stop the transaction. BEA completed the transaction not long before the court issued the inspection order. Subsequently, Elliot also filed a petition for unfair prejudice seeking to invalidate board resolutions in connection with the prior placement and to release substantial shareholders from any contractual obligations that restricted the sale of BEA, but this case is yet to be decided as of 10 December 2018.Footnote 95

From these two cases, it is clear that an injunction is more effective than an inspection order when a minority shareholder seeks to influence the controller. In theory, litigation would hurt the family controllers’ reputation and thus force them to settle or make changes. However, both BEA and eSun are controlled by locally prominent families, and the two cases had different results, so one might wonder how effective reputational sanctions actually are in influencing family controllers. Given the limited number of real-world examples, it is still too early to generalize, but it would be worth examining the effectiveness of future activism against controlling shareholders in Hong Kong.

4. Minority veto rights

RPTs are one of the main channels through which controlling shareholders divert corporate assets for their own benefit and expropriate minority shareholders,Footnote 96 and RPTs have also been a key topic in activists’ private engagements with controlled firms.Footnote 97 Shareholder activists can block a transaction if the law requires special approval by independent minority shareholders. This minority veto power is designed to protect the interests of minority shareholders in conflict-of-interest transactions, and it could be an effective legal tool for activists seeking to intervene in transactions in which a controlling shareholder is interested.Footnote 98 This approach has been adopted by Australia, Canada, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Israel, and Mexico.Footnote 99 Recent studies on Israeli companies show that minority veto rights are effective in constraining the pay of controller executives.Footnote 100 In Hong Kong, regulation grants minority shareholders significant rights in RPTs. According to Chapter 14A of the Listing Rules of the Stock Exchange of Hong Kong (SEHK), RPTs which fall within the stated definition need to be disclosed and submitted to the general meeting for approval by a majority of the minority shareholders (MoM approval).Footnote 101 Before submitting for shareholder approval, listed companies must set up an independent board committee to advise the minority shareholders based on the opinion of an independent financial adviser.Footnote 102 Aside from the more stringent rule on RPTs, the SEHK generally requires any shareholder who has a material interest in a transaction or arrangement to abstain from voting on a resolution approving that transaction or arrangement at the general meeting.Footnote 103 As long as the controlling shareholder is a party to the contract, or the contract confers upon the controlling shareholder or a close associate a benefit (economic or otherwise) not available to the other shareholders, that controlling shareholder cannot vote on the resolution.Footnote 104 In effect, all conflict-of-interest transactions that require shareholder approval under the SEHK Main Board Listing Rules require MoM approval. This requirement for an independent minority shareholder vote can mitigate expropriation by controlling shareholders.Footnote 105 In this case, controlling shareholders have an incentive to engage with minority shareholders who have a say in transactions.

Asset sales or acquisitions and equity sales with related parties account for almost 50 per cent of RPTs in Hong Kong.Footnote 106 Prior studies have considered these transactions to be more likely to result in the expropriation of minority shareholders than takeover offers or joint venture stake acquisitions or sales. Activists have also challenged these transactions in the past. For example, on 2 October 2007, Henderson Land Development (HLD) proposed the acquisition of the total equity stake that its subsidiary Henderson Investment Limited (HIL) held in Hong Kong and China Gas Company Limited (HKCG). HLD further promised to distribute the premium in the form of HLD shares and cash to shareholders of HIL upon completion of the asset sale transaction.Footnote 107 In response, Elliott Management increased its holdings from 5.01 per cent on 28 March 2007 to 9.01 per cent on 3 October 2007.Footnote 108 Later, HLD communicated with Elliott regarding the latter’s vote on the deal. On 7 November 2007, HLD increased the cash distribution from HKD 1.21 to HKD 2.24 per HIL share.Footnote 109 In light of the increased cash distribution, Elliott had undertaken to vote in favour of the transaction. Finally, the asset sale transaction was approved by independent shareholders at an extraordinary general meeting (EGM) on 3 December 2007.Footnote 110

Another example involves mergers proposed by controlling shareholders through schemes of arrangement. Under Hong Kong’s Codes on Takeovers and Mergers and Share Buy-backs (Takeovers Code), such proposals must be approved by at least 75 per cent of the disinterested votes, and the votes cast against the proposal cannot exceed 10 per cent of the disinterested votes.Footnote 111 This is stricter than the independent shareholder vote requirement for RPTs because the Takeovers Code not only requires a supermajority of the disinterested vote, but also grants minority shareholders who collectively own 10 per cent of the shares the right of veto over transactions that are not in their favour.

In a merger proposal, even if they do not hold more than 10 per cent of the shares, shareholder activists can persuade other minority shareholders through public campaigns that put pressure on controlling shareholders to improve their offer. The Power Assets Holdings Limited (Power Assets) case in 2015 is a good example of proxy advisors, who were not shareholders themselves, persuading minority shareholders to vote down a merger proposal. On 20 October 2015, Power Assets announced a merger proposal by its controlling shareholder, Cheung Kong Infrastructure Holdings Limited (CKI), which held 38.87 per cent of Power Assets shares at the time.Footnote 112 Proxy advisory firms Institutional Shareholders Services (ISS) and Glass Lewis considered the offer price too low and advised institutional shareholders to vote against the proposal.Footnote 113 As noted above, the votes cast against such a proposal cannot exceed 10 per cent of the total voting rights attached to all disinterested shares of the company.Footnote 114 In other words, the law grants minority shareholders a veto right against a buyout offer by controlling shareholders. In the Power Assets case, 50.8 per cent of minority shareholders approved the proposal, while 49.2 per cent voted against it;Footnote 115 the merger failed because the opposition from minority shareholders exceeded 10 per cent. Minority veto rights can indeed be powerful.

The SEHK Main Board Listing Rules provide additional minority protection for shareholders of listed companies. The specific transactions that require minority shareholder approval under the Listing Rules are: (1) connected transactions;Footnote 116 (2) voluntary withdrawal of listing from the SEHK, if the issuer has no alternative listing;Footnote 117 (3) rights issues or open offers that would increase the number of issued shares or the market capitalization of the issuer by more than 50 per cent;Footnote 118 (4) rights issues or open offers within twelve months after the commencement of securities dealings on the SEHK;Footnote 119 (5) refreshment of the general mandate (to allot, issue, or grant securities) obtained from the shareholders before the next annual general meeting;Footnote 120 (6) any major transaction or substantial disposal or acquisition of assets as determined by various ratios set by the SEHK;Footnote 121 (7) a reverse takeover with a change in control resulting from an acquisition or a series of acquisitions of assets by a listed issuer which constitutes an attempt to achieve a listing of the assets to be acquired and a means to circumvent the requirements for new applicants;Footnote 122 (8) acquisitions, disposals, transactions, or arrangements that would result in material changes within twelve months after the commencement of securities dealings on the SEHK;Footnote 123 and (9) spin-off proposals.Footnote 124

III. SHAREHOLDER ACTIVISM IN HONG KONG

A. Activists’ Initiatives Against Controlled Firms in Hong Kong

To investigate how the law influences strategy planning and activism outcomes in practice, this study collected data on activist initiatives against companies listed in Hong Kong from April 2003 to April 2017. It excludes activist activities by individuals and those against companies without a controlling shareholder, and focuses only on activist activities initiated by institutions, because they have more financial resources and professional knowledge than individuals and are more capable of employing legal tools to exert influence on controlling shareholders.Footnote 125 In addition, institutions usually have much larger stakes in the company and thus have a stronger incentive to intervene. Prior studies in the US generally focused on hedge funds.Footnote 126 However, large mutual funds and index funds, like BlackRock and Vanguard, have recently joined the activist ranks and expect to participate more aggressively in changing the corporate governance landscape of public companies. Similarly, proxy advisors like ISS and Glass Lewis are becoming more aggressive in overseeing public firms. Therefore, this article looks not only at activists’ actions initiated by hedge funds, but also those by institutional investors and proxy advisors.

This study selected cases from two main sources. First, Part XV of the Hong Kong Securities and Futures Ordinance (SFO) requires a person to notify the SEHK and the listed company of his or her interest once this person becomes interested in (through either a long or a short position) 5 per cent or more of the voting rights. The Disclosure of Interests form (DOI form), which is similar to Schedule 13D in the US, is available from the SEHK disclosure database.Footnote 127 Following the method adopted in prior literature,Footnote 128 this study searched DOI forms from 1 April 2003 to 30 April 2017 for the names of the activists listed in the Top 50 Activist Investor Profiles provided by The Conference Board as well as other local activists, which were obtained through searching Google and the business news database Factiva.Footnote 129 Second, there might be other activist initiatives in which the activists did not invest at least 5 per cent in the firm and thus might not be covered in DOI filings. To capture those cases, this study also employed a general search on Google and Factiva for activist initiatives in Hong Kong. It excluded cases involving only strategic investments and merger arbitrage transactions that showed no signs of activism. Ultimately, this study identified twenty-four activist initiatives from 1 April 2003 to 30 April 2017. There are, however, some limitations to this study. As mentioned earlier, many activist engagements take place behind closed doors. The observations made by this study are only limited to those made public or reported by the media. In addition, this study does not include lobbying activities undertaken by activists.

Unlike prior research, this article focuses on the role of legal institutions. Therefore, it also collects data on the legal strategies adopted by activists, the outcomes of these strategies, the percentage of shares held by activists, the identities of controlling shareholders of the target firms, and the percentage of shares held by controlling shareholders. This data was collected through company disclosure documents and annual reports on HKEXnews, business news on the Factiva database and on the internet more generally, court judgments, and case studies conducted by Wong.Footnote 130

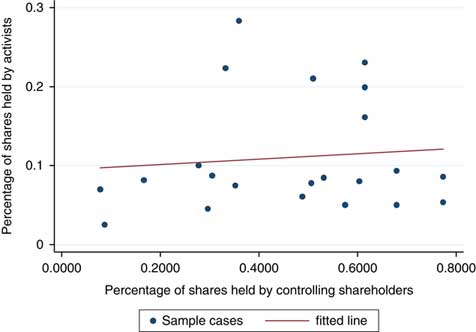

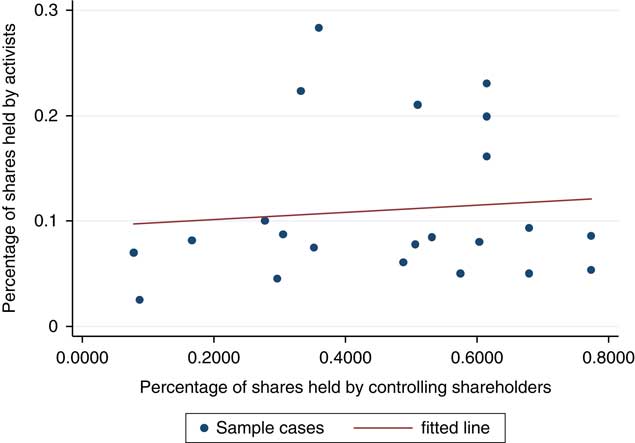

A list of the twenty-four activist events and relevant information appears in the Appendix. Table 1 provides the summary statistics by percentage of shares held by activists and controlling shareholders, forms of engagement, types of activists, types of demands, whether formal legal mechanisms were involved, and outcomes. Two-thirds of the engagements were conducted privately and only one-third resorted to public engagement. 71 per cent of cases were initiated by hedge funds, with an average activist shareholding of only 11 per cent. The average controllers’ shareholding in target firms was around 50 per cent. As shown in Figure 1, share percentages held by controlling shareholders varied widely, while those held by activists were generally under 30 per cent. From the fitted line, we can see a slight positive relation between the shares held by activists and those of the controlling shareholders, so it appears that activists have to acquire more shares when controlling shareholders control a higher percentage of shares.

Table 1 Summary Statistics

Note: N is number of cases, mean is the average, St. Dev. is standard deviation.

Figure 1 Percentage of shares held by controlling shareholders and activists in sample cases

B. Discussion and Analysis

Based on the data collected, this part explores the role of legal mechanisms in activists’ strategy planning and outcomes. Specifically, this part addresses three questions. Does the availability of legal remedies affect activists’ decisions to engage and make demands? Does the ownership level of controlling shareholders affect activists’ engagement and legal strategies? Finally, do cases where activists resort to formal legal mechanisms have a higher success rate?

1. Most activists’ initiatives involve corporate governance disputes where legal remedies are available to them

Hirschman famously argued that investors influence corporate governance or business decisions through ‘exit’ or ‘voice’, and that these two actions are complementary. The chances for a voice to be heard are greatly strengthened by the threat of exit.Footnote 131 In the presence of a controlling shareholder, the odds of winning an activist campaign are slim. Activists are unlikely to initiate an action unless they believe they have a realistic chance of winning. Extending the view that voice and exit are complementary, this article argues that exit and the threat of commencing a legal claim arising from a corporate governance dispute are substitutes. Activists’ chances to speak out for a change in controlled firms will be greatly increased if the matter involves corporate governance disputes. In theory, if the matter involves corporate governance disputes, activists usually have a legal claim against the company and can exert leverage using those rights to increase their bargaining power to call for changes. Thus, a greater percentage of activist initiatives should involve corporate governance disputes, where activists can rely on legal protections to enhance their bargaining position. A previous survey of institutional investors also shows that investors who choose to engage do so more often because of concerns about corporate governance or business strategy rather than due to short-term issues.Footnote 132

To investigate whether the availability of legal remedies affects activists’ strategy planning, this study categorizes activist initiatives into two types: governance demands and pay-out demands. Governance demands are activist initiatives that seek to correct errors in corporate governance. This type of demand is usually triggered by certain corporate decisions, and typically involves unfair treatment of minority shareholders or important corporate reorganization decisions. In contrast, a pay-out demand is a purely financial demand, usually by hedge funds, that seeks a pay-out from a firm in the form of either special dividends or share buyback. As shown in Table 1, among the twenty-four publicly disclosed activist initiatives in Hong Kong, two-thirds (sixteen out of twenty-four) involve governance demands; only one-third (eight out of twenty-four) are pay-out demands. Consistent with this author’s expectation, a greater percentage of activist initiatives involve corporate governance disputes, where activists can rely on legal protection to enhance their bargaining position. Among the sixteen governance demands, seven involve conflict-of-interest transactions, usually with controlling shareholders or parent companies; three involve corporate governance concerns such as improper private placement transactions; and three involve corporate restructuring decisions. These two types of demands, however, are not mutually exclusive and sometimes even complement each other. A shareholder activist might press the firm to distribute special dividends – a pay-out demand – in the shadow of a governance demand. For example, in the case of the privatization of Pacific Century Premium Development (PCPD), Elliott first threatened to vote down the privatization offer proposed by the controlling shareholder – a governance demand – if the controlling shareholder declined to increase the buyout price. Later, taking advantage of the privatization turmoil, Elliott continued to increase its shareholding and pressed PCPD to issue a special dividend – a pay-out demand.

2. Activists tend to avoid public engagement and refrain from exercising their legal rights when controllers own a majority of shares

Second, this article examines the relationship between the ownership level of controlling shareholders and activists’ engagement and legal strategies. Most large public companies in Hong Kong are dominated by family controllers, and it is well documented that the reputation mechanism works best in family conglomerates.Footnote 133 Unless a minority investor in a controlled firm has a strong legal claim, the investor’s best odds of having demands heard by a controlling shareholder is to maintain an amicable relationship and engage privately with controlling shareholders. Otherwise, an effective controller who has strong and stable corporate control can simply refuse to respond to any demand. Therefore, activists might prefer to engage privately with controllers who control the majority of the shares. As for legal strategies, it is clear that if the controller controls the majority of the shares, activists should avoid seeking board representation because the controller will be able to win all the board seats under the majority voting rule. In theory, the ownership percentage of controlling shareholders should not matter much in cases where activists commence legal proceedings; what determines litigation outcomes should be the strength of the activists’ legal claim. Nonetheless, what we learn from the Elliott case is that timing is of utmost importance in the business world. While the court may eventually serve justice for activists, the incumbents who control the company and its meeting procedures may nevertheless have completed the transaction or business restructuring long before the court hands down its verdict. Therefore, the controllers’ shareholdings – which determine the level of control they have over corporate affairs – may still matter even in cases involving court proceedings.

Overall, private engagement is the dominant and preferred mode of communication between activists and companies in Hong Kong, which is consistent with other parts of the world.Footnote 134 In practice, there are unobservable and undocumented private engagements going on behind the scenes. Even in the publicly disclosed cases collected in this study, two-thirds (sixteen of twenty-four) of activist demands in Hong Kong were made through private engagements. Activists brought their claims to the media in only one-third of the cases. On the other hand, even though activists chose to engage privately in most cases, that does not mean that activists would categorically avoid employing formal legal mechanisms to strengthen their bargaining power. Cases in which activists decided to utilize formal legal mechanisms account for a little less than half (42 per cent) of the samples (see Table 1).

Two t-tests were conducted to compare the mean values of controllers’ shareholding percentages in situations where activists chose whether to engage privately or publicly and whether to rely on formal legal mechanisms. It is expected that when confronting controllers with majority shares, activists would choose to engage with them privately and not to exercise their legal rights. This article finds just such an outcome in Hong Kong. As Table 2 shows, the average stake held by controlling shareholders in cases where activists opt for private engagement was 58.71 per cent, which was 33.52 per cent higher than in cases involving public intervention. Similarly, the average shareholding of controlling shareholders in cases with no legal mechanism was 53.36 per cent, which was 13.97 per cent higher than cases that involve formal legal mechanisms. The differences are statistically significant at the 1 per cent and 10 per cent level, respectively. (t(22)=5.63, p<0.01; t(22)=1.67, p<0.10) It appears that the gap between cases with or without legal mechanisms is smaller than between cases where activists engaged privately or publicly. I hypothesize that it is because controllers’ ownership level does not matter much in cases involving minority veto rights, where the activists’ own shareholding level is at stake. Overall, activists tend to avoid making their intervention public, and to avoid exercising their legal rights when controllers own a majority of the shares.

Table 2 t-test results comparing the percentage of shares held by controlling shareholders

Note: N is number of cases, mean is the average, St Dev is standard deviation, t is t-test result, Df is degree of freedom, and p refers to the p-value.

3. Cases that involve formal legal mechanisms have had a higher success rate

Finally, this part examines whether cases where activists resort to formal legal mechanisms have had a higher success rate. Overall, cases involving formal legal mechanisms appear to have had a higher success rate. Table 1 shows that 42 per cent of the cases studied involve formal legal mechanisms, including board representation, court orders, litigation, minority veto rights, shareholder proposals, and calls for extraordinary general meetings. The average success rate of cases involving formal legal mechanisms was 66.67 per cent, while cases where formal legal mechanisms are absent was 64.28 per cent (Table 3). At face value, it seems that there is not much difference between the two sets or cases. However, cases where activists commenced litigation or applied for court orders tend to be tougher cases where activists face strong opposition from the controlling shareholders. Arguably, the fact that activists succeed 50 per cent of the time when litigation is involved means that 100 per cent of their success can be attributed to litigation – because those cases would have certainly failed had litigation not been involved. In this sense, use of formal legal mechanisms does increase the odds of activists’ demands succeeding.

Next, this study tries to assess the effectiveness of individual legal strategies, namely seeking board representation, court orders, litigation, and minority veto rights in conflict-of-interest transactions. While seeking board representation appears to be a popular form of activism in both Italy and the US, this method is rare in Hong Kong.Footnote 135 Unlike its Italian counterpart, Hong Kong law does not offer minimum board representation for minority shareholders. In addition, since dual-class shares were not allowed in Hong Kong-listed companies until April 2018, there is no practice of granting outside shareholders the right to nominate and elect minority board representatives, as would be the case in some US dual-class companies.Footnote 136 Cumulative voting, which favours minority shareholders, is not mandatory under Hong Kong law and is rarely adopted by Hong Kong-listed companies.Footnote 137 In general, the odds of obtaining minority seats on the boards of Hong Kong-listed companies are slim. We also observe similar results in our sample. Out of twenty-four activist initiatives, only one sought board representation.

Litigation and court orders are also rare. Only three actions in the study involved formal court proceedings, with only one succeeding. This is not surprising because Hong Kong mainly relies on public rather than private enforcement. Shareholder litigation is rare because securities class actions are not available in Hong Kong and the procedural rules for shareholder derivative actions do not favour plaintiff shareholders.Footnote 138 In Hong Kong, the SFC is the main driving force in the enforcement of corporate and securities law.Footnote 139 However, as mentioned earlier, cases involving court proceedings tend to be tougher cases. The two major cases involving court proceedings are the Elliott case and the Passport case. In both cases, activists tried to stop a private placement proposal that might benefit controlling shareholders. Even though only Passport was able to stop the unfair transaction, bringing legal proceedings can still help activists in the battle against controlling shareholders because in the absence of these proceedings, both transactions would have been completed as the controlling shareholders desired.

Finally, this study finds that the most effective legal mechanism against controlling shareholders is the use of minority veto rights. As discussed in Part II.B.4, minority veto rights are a legal tool that can substantially increase hedge funds’ or institutional shareholders’ bargaining power. Among the twenty-four activist events in this study, four either required MoM approval or minority shareholder veto rights. The four cases all involve transactions with parent companies, including HIL’s asset sales to the parent company (2007), PCPD’s privatization offer by the parent company (2008), Power Assets’ proposed merger with the parent company (2015), and GOME Electrical Appliances Holding Limited’s (GOME Electrical) asset purchase from the parent company (2015) (see Appendix). Among the four activist events, all the activists’ demands were met regardless of whether they made the demand publicly or privately, for a success rate of 100 per cent (see Table 3). The activists forced the controller to sweeten the offer in an asset sale transaction or to reduce the price for an asset purchase transaction, or were able to use their veto rights to vote down a privatization or merger proposal.

Table 3 Success Rate of Activists’ Actions with Formal Legal Mechanisms

4. Policy implications

In sum, this article finds that legal mechanisms appear to help activists win battles against controlling shareholders. The case studies show that among all the legal mechanisms, minority veto rights are the most commonly used, and are quite effective as leverage. If policymakers were to encourage activists or enhance minority shareholders’ bargaining power against controlling shareholders, requiring MoM approval or giving outside shareholders veto power (eg, stipulating that votes cast against a proposal cannot exceed 10 per cent of disinterested votes) on certain matters could be a justified option. This part discusses the potential of applying minority veto rights, including MoM approval, to RPTs, freeze-out transactions, the appointment of independent directors, and executive remuneration.

At present, the most common application of MoM approval is in RPTs. Besides Hong Kong, other jurisdictions, including Australia, Canada, France, Israel, and Mexico, require MoM approval over RPTs.Footnote 140 MoM approval also applies to controlling shareholder squeeze-out transactions, where controlling shareholders use their majority power to force out minority shareholders and obtain full control over the firm, typically for the purpose of taking a listed company private. The EU Takeover Directive requires 90 to 95 per cent of votes for a mandatory squeeze-out in a tender offer situation, which essentially gives minority shareholders veto rights.Footnote 141 Hong Kong has a similar 90 per cent mandatory squeeze-out rule by which an offeror that acquires 90 per cent of the shares in a takeover tender offer may squeeze out the rest of the minority shareholders.Footnote 142 The other way to squeeze out minority shareholders in Hong Kong and most other Commonwealth jurisdictions is through a scheme of arrangement, which is similar to statutory mergers in other jurisdictions but involves court intervention. To implement a scheme of arrangement and squeeze out minority shareholders, the law requires 75 per cent of disinterested votes to be in favour of the proposal, with no more than 10 per cent of disinterested shareholders voting against.Footnote 143 The scheme of arrangement procedure not only requires (super-)MoM approval but also gives 10 per cent of disinterested shareholders a veto right to block the transaction, which greatly enhances the bargaining power of any shareholder who can wield at least 10 per cent of the votes. The US follows a different approach in regulating squeeze-outs but also favours MoM approval. The Delaware Supreme Court applies a lower level of judicial scrutiny to a controlling shareholder squeeze-out transaction if such a transaction has been approved by an effective disinterested board committee and by MoM approval.Footnote 144

The third area of application could be in the appointment, re-appointment, and removal of independent directors, who have been regarded as important in monitoring controlling shareholders, especially in conflict-of-interest transactions. However, most jurisdictions leave appointment and removal power in the hands of controlling shareholders.Footnote 145 Without a different election voting rule that constrains controlling shareholders’ voting power, it is unlikely that independent directors will act for the minority shareholders in cases where to do so would be against the wishes of the controlling shareholders. Scholars have suggested that granting minority shareholders veto rights would enhance the independence of independent directors and their accountability to public investors.Footnote 146 Some jurisdictions have granted minorities different forms of veto rights in the election or removal of independent directors. For example, the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority adopted new rules to enhance corporate governance of controlled firms in 2014,Footnote 147 under which the election and re-election of independent directors are subject to a ‘dual-voting’ structure that requires both majority votes and MoM approval. This voting structure balances the interests of controlling and minority shareholders.Footnote 148 Israel and Italy also grant similar veto rights to minority shareholders to enhance the independence of directors.Footnote 149 Against the backdrop of the rise of dual-class share firms where controlling shareholders enjoy leveraged corporate control through super-voting shares, policymakers could consider requiring MoM approval or other forms of minority veto rights in the appointment, re-appointment, and removal of independent directors.Footnote 150

The final potential area of application is the remuneration of controlling shareholders who serve as directors or executives in the firm. ‘Say on Pay’ reforms have been advocated and implemented in several major jurisdictions over the last decade. However, most reforms only require non-binding votes by shareholders, and thus cannot effectively constrain potential tunnelling by controlling shareholders through excessive executive pay. Israel adopted a new rule in 2011 requiring MoM approval of pay packages for executives who are also controlling shareholders (controller executives). A recent empirical study on the 2011 Israeli reform shows that MoM approval does indeed constrain the pay of controller executives, lowering the average by 10 per cent.Footnote 151 Requiring MoM approval or other forms of minority veto rights in controller executives’ remuneration could be the next policy move to rein in controlling shareholders.

How controlling shareholders may be better constrained has been a frequent topic of policy and academic discussions of corporate governance of controlled firms. The use of minority veto rights together with the exercise of shareholder rights by activist institutional investors or hedge funds may help restrain opportunistic behaviour by controlling shareholders. US practitioners have raised some concerns about potential abuse of such minority shareholder rights by activists who might acquire sufficient shares in the market to block the transaction for personal gains.Footnote 152 This article argues that concerns with such ‘holdouts’ are unwarranted. Case studies in the US reveal that active shareholders do not appear to abuse minority rights purely for arbitrage.Footnote 153 Rather, the cases presented in this article show that activists help individual shareholders to better evaluate proposals presented by controlling shareholders, particularly in going-private transactions, and force controlling shareholders to increase offers, which benefits all shareholders.Footnote 154 It makes no business sense for activists to block the transaction if the transaction appears to benefit the company as a whole. Furthermore, in a buy-out or privatization offer, it is also not to the advantage of activists to refuse an offer with a fair price and risk staying with the company as a minority for good. Furthermore, activism can help cure the collective action problem faced by individual shareholders and the general passivity of shareholders who choose to exit a firm rather than use their voice to demand change. Therefore, minority veto rights can be seen as a regulatory innovation that simultaneously empowers the minority and keeps management power in the hands of controlling shareholders.

IV. CONCLUSION

Shareholder activism against controlled firms has thus far been rare. Conventional wisdom holds that the existence of controlling blocks serves as a natural and powerful defence against activism. This article explores whether and how activists use legal tools to enhance their bargaining power against controlling shareholders. Based on hand-collected data on activist initiatives against controlled companies in Hong Kong from 2003 to 2017, this article finds that resorting to formal legal mechanisms appears to increase the success rate of activists’ demands. Activists in Hong Kong have applied for court orders, filed litigation, and exercised minority veto rights in conflict-of-interest transactions. Among these options, minority veto rights appear to be the most commonly used and effective legal tool for activists when leveraging their relatively small shareholdings in controlled firms. Furthermore, the availability of legal remedies itself and the level of shareholding by controllers affect activists’ strategy planning. Most actions against controlled firms involve corporate governance disputes where the law offers specific protection to minority shareholders. With such legal rights at hand, activists see a greater chance of winning the battle and are therefore willing to initiate engagement with controlling shareholders. On the other hand, when controlling shareholders hold a majority of shares, activists tend not to make their engagement public and also not to exercise their legal rights.

With more activists targeting firms in Europe and Asia, shareholder activism against controlled firms will only become more prevalent in the future. In the presence of controlling shareholders, the channels through which activists can exert influence on controlled firms matter more than the percentage of shareholdings that activists own. This article contributes to existing scholarship by pointing out the role of legal institutions in facilitating proactive monitoring of firms by external shareholders. This is not to say that activists face no challenges once granted veto rights. On the contrary, the toughest battle arguably lies ahead. To facilitate shareholder stewardship in controlled firms, policymakers should consider requiring majority-of-the-minority approval or granting minority shareholders veto rights in specific matters to enhance the corporate governance of controlled firms.