In September 1918, a Romanian police agent in the city of Chișinău, the capital of the eastern borderland region of Bessarabia, found himself in the midst of a strange religious service, a hodgepodge of peoples and languages. Leading the group was Lev Averbuch. He was Jewish and from Odessa in neighbouring Soviet Ukraine. He and his wife Maria both converted from Judaism to Christianity at the turn of the twentieth century and identified most with the Baptist denomination. They travelled across Eastern Europe speaking at various Protestant churches but also in prisons, hospitals, and theatres. As missionaries with the London-based organisation Mildmay Mission to the Jews, they finally settled in Chișinău in 1918.

Averbuch was similar to other influential Eastern European Jewish converts of his time, such as Joseph Rabinovich, Chaim Yedidiah ‘Lucky’ Pollak, and Yechiel Lichtenstein.Footnote 1 Born on 31 July 1885 in Zhabokrich/ ז׳בוקריץ׳/Жабокрич, Podolia, a shtetl in what is today Ukraine, to a ‘well-to-do family,’ Lev was one of eight children. His parents were Haia and Iacov Averbuch.Footnote 2 Like other prominent Jewish Christians at the turn of the twentieth century, he was influenced by the Haskalah – the Jewish enlightenment – and left his Orthodox Jewish upbringing to study chemistry and music in Odessa, where he formed his first of many orchestras.Footnote 3

Averbuch became a Christian, or what he termed a ‘true Israelite,’ convinced Jesus was the Messiah in 1910 after studying the Christian scriptures and the Jewish Tanach.Footnote 4 He was also greatly influenced following discussions with Russian writer and former Orthodox priest Vladimir Martsinkovsky.Footnote 5 In 1913 Lev joined the English organisation Mildmay Mission to the Jews along with his wife, Maria.Footnote 6 Mildmay Mission to the Jews, one of the largest and best equipped missions to the Jews of its time, was founded in London in 1876 by John Wilkinson. It was non-denominational and dedicated to sharing the Christian faith with Jews and distributing Christian literature.Footnote 7 The Mildmay Mission's monthly publication Trusting and Toiling on Israel's Behalf reveals Lev and Maria's extensive travels and their involvement in the organisation's chapter in Odessa from 1913–17, before they finally settled in Chișinău.Footnote 8

It is unclear how the Averbuchs came to be stationed in Chișinău. In September 1917, while in Odessa, Lev wrote of greater liberty in the Republic of Russia after the 1917 February Revolution compared to previous Tsarist rule, and hoped that Jews of the Christian faith would no longer ‘suffer both from the oppression of the authorities and from the absence of Christian kindness among fellow-believers.’Footnote 9 He intended to work in Russia and at the start of 1918 the Averbuchs were listed as working for Mildmay in Moscow. However, Romanian police registered their arrival in Romania at the end of August 1918 through the Bender/Tighina border-crossing holding Ukrainian passports.Footnote 10

Two Norwegian Lutheran missionaries from the southeastern Romanian port city of Galați, visiting Baptist believers in Chișinău that same summer of 1918, claimed Lev and Maria were prevented from returning to Russia due to the closing of Romania's borders with the Ukraine.Footnote 11 The Averbuchs were, therefore, reassigned as Mildmay missionaries to Chișinău. For the next twenty years, they used their international connections and their local knowledge to build a peculiarly diverse and attractive religious community. Due to uncertain political and social situations described in more detail below, especially in the border region of Bessarabia so close to the Soviet Union, agents of the Romanian secret police, the Siguranța, kept detailed reports on the activity of Averbuch and the members of his community.

The interwar period across the whole of Europe was one of escalating political and religious tensions among groups seeking to influence social, cultural and economic policies towards national consolidation. These were the nationalising processes that took place after the peace treaties of the First World War in many of the successor states that replaced the collapsed empires of Central and Eastern Europe. Such was the case in the newly enlarged Kingdom of Romania, which was one of the countries to receive the most territories as a result of the Paris peace treaties. The region of Bessarabia, with its capital city of Chișinău, was previously part of the Russian Empire. Romanian authorities considered it the most backward region acquired by Romania after the First World War due to the high level of illiteracy, large rural populations, lack of infrastructure, and its mostly Russian-speaking elites.Footnote 12 Romanian leaders saw the presence of Russified elites as an impediment to Romanian culture and language in the area. They also hindered ‘Romanianisation’ policies that sought the social, political and economic advancement of the Romanian language and the ethnic Romanian population over that of other minorities.

The Romanian government, therefore, sought to apply more stringent ‘Romanianisation’ policies in an attempt to make Bessarabia completely ‘Romanian’ in language, institutions and culture.Footnote 13 Its proximity to Soviet Ukraine made the region more susceptible to Bolshevik influences in the eyes of Romanian authorities. All these elements, along with violent unrest in places such as Tatarbunar, led to the installation of martial law in Bessarabia for most of the interwar period.Footnote 14 The archives also reveal the prevalence among Romanian government and religious authorities of the belief in the Judeo-Bolshevik threat – that Jews were conspiring to spread communism internationally and especially in Bessarabia with its large Jewish population and its location bordering the Soviet Union.Footnote 15 Averbuch's community functioned amid this state of emergency and under constant surveillance.

An important factor in Romania's national consolidation policies was religion, specifically the dominant Romanian Orthodox Church (Biserica Ortodoxă Română, hereafter BOR), representing most ethnic Romanians in the country. BOR was intricately linked with Romanian national identity and its authority and status in Greater Romania was thought to be challenged by the new populations of other faiths. The Romanian Patriarchate based in Bucharest especially pushed a nationalist agenda, even if Orthodox churches in the newly acquired regions previously worked in more multi-ethnic, multi-confessional contexts.Footnote 16 Government policy and BOR actions against the Orthodox separatist groups called Inochentists in Bessarabia were particularly harsh.Footnote 17 The Catholic Csangos in northern Moldova also found their ethnic and national identity disputed and ethnologists arguing over their Romanian or Hungarian origins.Footnote 18

The rapidly growing ‘sectarian’ groups of evangelicals, in particular the Baptists, to whom the Averbuchs belonged, were most numerous in the regions of Bessarabia in the east, bordering Soviet Ukraine, and in Transylvania in the west, bordering Hungary.Footnote 19 These evangelicals created concern for Romanian state authorities, who believed they would lose the previously mentioned territories if the populations in them were not thoroughly ‘Romanian,’ which in this case also meant being Eastern Orthodox in religion.

In Romania, evangelicals spread from ethnic Hungarian, German, Russian and Ukrainian communities, as well as through Romanian labourers from America returning home, to the majority ethnic Romanian population and met increasing success in rural areas, especially in Transylvania and Bessarabia, where they grew exponentially.Footnote 20 Their ties to ‘foreigners,’ both domestic (ethnic minorities in the region for centuries) and international, led government officials and BOR to regard them with suspicion, accuse them of being foreign pawns and pass legislation to curtail their activity.Footnote 21 Depending on who was in government, evangelicals were at times forbidden to meet, marginalised in education or at work, and experienced violence at the hands of local gendarmes or neighbours.Footnote 22

The Baptist church in Chișinău, Bessarabia, presented a case of special concern due to Lev Averbuch's position of leadership within the church. Romanian authorities considered him a double threat as both a ‘sectarian’ and a ‘Russian’ Jew. The growth of his separate non-conformist multi-ethnic congregation, which included a high percentage of Jews, was a challenge to both BOR and the state's attempts at religious, cultural and linguistic homogenisation to protect the rights of the majority Romanian population.

It is important to remark that due to regional differences across Romania, some BOR leaders also failed to comply with nationalisation policies sent from the central or local authorities. For example, Archbishop Gurie Grossu of the Orthodox Church in Bessarabia encountered problems among his churches with amending the liturgical calendar, the issue of ecclesiastical property and schools, the publication of newspapers in Cyrillic, the election of bishops and the disciplining of priests.Footnote 23 Though the Orthodox Church in Bessarabia did not have the same agency or success in regards to the nationalisation policies of the central and local authorities, it and BOR leaders in Bucharest and in other regions still pressured the state authorities to take action against sectarians like Averbuch and his group.

Sources for the article are drawn mostly from two large folders from the National Archives of the Republic of Moldova, comprised of surveillance reports conducted by Romanian secret police, the Siguranța, as they monitored Averbuch's group for any dangerous activity. The other most widely used sources are the religious newsletters Trusting and Toiling from Mildmay Mission to the Jews, the Hebrew Christian from the International Hebrew Christian Alliance, and Averbuch's own Blagovestnik, which document the activities, the successes and even the failures or needs of the group. Erich Gabe's memoirs published in the 1990s in the Hebrew Christian were also carefully checked with the previously mentioned sources.

The two types of sources, government and religious communities, provide evidence of how government or BOR authorities viewed Averbuch's group as well as how the group saw itself. The Siguranța archival reports contain many erroneous labels and accusations made by police or by BOR priests and Jewish rabbis angry at the evangelical proselytising techniques of Averbuch. The religious publications, on the other hand, strive to paint the community in the best light. Nevertheless, many of the details regarding the large number of attendees, the attractive music, the many languages used, and the sermons against nationalism and antisemitism are corroborated in the police files. The triage of sources reveals how Averbuch and his group reflected the larger trend among religious minorities to put their faith identity above that of their national identity.

The article contributes to valuable studies by Radu Cinpoeș, R. Chris Davis, James Kapalo, and Roland Clark on Romanian national identity construction by developing even further the importance of religious identity in the nation-building process.Footnote 24 For Averbuch's group, their faith was of greater importance than their nationality. It adds increased nuance through the lens of lived religion to the debates on national indifference and supports historian Andrei Cusco's arguments on how national identities were instrumentalised or, in Avebuch's case, condemned.Footnote 25 Religious minorities challenged nation-building processes in the borderlands, similar to what James Kapalo argues in his study of the Orthodox separatist group called Inochentists, who also experienced strict government surveillance in Bessarabia.Footnote 26

The story of the Jewish Christians of Chișinău reveals the intersection between ethnic and religious minorities and the creation of a double or even triple minority. Jewish evangelicals were an ethnic minority among Romanians, a religious minority among the majority Eastern Orthodox, and a marginalised apostate minority in the Jewish communities. Rather than focus on conversion of Jews to the dominant religions (specifically Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox), the case of interwar Romania reveals the appeal of evangelical/non-conformist groups to both Jewish Orthodox and assimilated Jewish individuals. This is a fascinating element not previously examined. Their conversion occurred at a very crucial period of increasing antisemitism and simultaneously increasing anti-sectarianism in Romania.

Historians of religious and ethnic groups in imperial Russia, Sergei Zhuk and Ellie Schainker, identified growing Jewish interest in evangelical denominations at the turn of the nineteenth century, an interest that continued into the twentieth century across eastern Europe, despite the repression evangelical groups faced.Footnote 27 Todd Endelman's study of Jewish converts in Warsaw, Poland, identified overwhelming conversion to Protestantism and attributed it to a less ‘rigorous pre-baptismal examination’ as well as to ‘militant’ Anglican and Lutheran missionary work.Footnote 28 The article comes alongside these works and that of David Ruderman on the concept of ‘converts of conviction’ to demonstrate why these evangelical groups, without a history of antisemitism, were so appealing to converts.Footnote 29 It employs thick description to present this unique case and better understand the communal as well as individual convictions and actions that created such an inclusive environment actively opposed to nationalism.

Some interwar church or state authorities saw the evangelicals as influential on a global scale with the potential to provide ways to escape oppression via emigration to the United Kingdom or the United States. However, this was not a guarantee, and Western co-religionists’ influence on religious policy was limited.Footnote 30 Nevertheless, Jewish individuals along with other ethnic minorities, continued to join evangelical churches. Dangerous affiliations with ‘foreign organisations’ and taking on more minority statuses, reveal the intimate and complicated bond of faith and identity beyond that of national or ethnic identification at the local level in interwar Romania.

The new Romanian evangelical churches more readily accepted new members without taking issue with an individual's ethnic background and had no history of antisemitism.Footnote 31 Colporteurs of the Anglican organisation Church's Mission to the Jews (formerly the London Society for Promoting Christianity amongst the Jews, LSPCJ) reported cooperation with ‘evangelical Christians,’ who lent out their meeting halls, advertised meetings, and when possible even followed up with Jewish guests who attended the services.Footnote 32

It was this openness and little to no history of antisemitism in the relatively new evangelical churches that made them more appealing to some Jews, like Averbuch, rather than BOR, the Greek Catholic, or the Roman Catholic Churches. Henry Ellison, who worked first in Bucharest with the Anglican LSPCJ and then with Mildmay Mission to the Jews in Cernăuți, maintained that Baptists had been closely connected to Jewish missions in Romania from its beginnings.Footnote 33 Jewish Christian leaders in Romania, affiliated with evangelicals, came into their own across the country in the interwar period: Moses Richter in north-eastern Cernăuți city, Isaac Feinstein in the south-eastern port city of Galați and the north-eastern city of Iași, Henry Ellison in the capital city Bucharest, and of course, the main protagonist of this study, Lev Averbuch in Chișinău.

According to Schainker's groundbreaking study on Jewish conversion in imperial Russia, the relationship between conversion, confessional choice, and minority integration, challenges the instrumentalist argument that Jewish conversion to Christianity was a means to becoming modern, European, or proving patriotism to the nation-state.Footnote 34 The present work provides an important case study from interawar Romania in support of her argument and for Ruderman's previously mentioned concept of converts of conviction, revealing the role of faith and belief as factors influencing conversion and leading to a double or triple minority status. The article adopts Schainker's definition of conversion as ‘a social encounter with the peoples and institutions of neighboring confessional communities’ that results in a change of beliefs and of prior religious affiliations, influenced by ‘local conditions, social spaces, and networks.’Footnote 35 In this article, the section on ‘Members, Converts, True Jews’ provides an analysis of how Averbuch and his group understood their new Jewish-Christian identities within the larger context of conversion to evangelical groups.

Lev Averbuch's work in Chișinău was the most fascinating connection between Jewish Christians and these new evangelical faiths in interwar Romania. His work was a catalyst for similar congregations across Romania and for a new vision of Jewish and Christian identity - one that challenged clear ethnic-national-religious categories. Though well-known and kept under strict surveillance by police at the time, this unique multi-cultural, multi-lingual community was largely forgotten by historians and non-academics alike. The present study brings to light their activities, theology, and relationships with other groups to show how religious minorities challenge the understanding of exclusive interwar ethnic and religious communities and how they demonstrate the fluidity of religious, ethnic, and even geographic borders in the borderland of Bessarabia.

The Importance of a Forgotten Borderland

Chișinău (previously Kishinev), as the capital city of the former Russian and later Romanian territory of Bessarabia, was an appropriate place for the multi-ethnic, inter-denominational work of Averbuch and his group to thrive.Footnote 36 In 1930, Chișinău was the second largest city in Romania with a Jewish population of 35 per cent. It included more synagogues than churches: sixty-five synagogues, thirty-eight Orthodox churches and a growing number of Protestant and evangelical churches.Footnote 37 The city had a history of multi-confessionalism, with a surprisingly high percent of Jewish conversions happening outside the dominant Russian Orthodox Church during the Russian Empire, in spite of benefits denied those who joined ‘schismatic sects.’Footnote 38 Chișinău, along with Odessa, were considered major scenes for the spread of evangelical Christian non-conformist groups in the southwestern corner of the Russian Empire (or today's Republic of Moldova and central Ukraine). These groups paved the way for Kishinev (later Chișinău) to become the birthplace of the modern Jewish Christian/Messianic movement led by Joseph Rabinovich in 1884.

Averbuch would rely heavily on Rabinovich's legacy, even if diverging in points of theology or religious practice.Footnote 39 He often mentioned Rabinovich or tied his work back to this pioneering Jewish Christian leader in his reports back to the Mildmay Mission organisation. Both Rabinovich and later Averbuch were connected to the rapidly spreading Ukrainian Stundist peasant movement. Stundism, a Christian reform movement largely influenced by German colonists, emerged in the late nineteenth century in the southwestern part of the Russian Empire. It became most closely associated with the evangelical Baptist and Brethren movements, with which Averbuch was associated. Police viewed it as sectarian, and it was suppressed by the Russian Orthodox Church in the nineteenth century.Footnote 40

Chișinău was also the scene of the 1903 Kishinev Pogrom – the event most associated in Jewish collective memory with modern European antisemitic violence prior to the Holocaust.Footnote 41 Averbuch paid homage to those who died in the pogrom by taking visitors from his congregation to Aziatskaia Street and reminding them of the violence that took place there because of nationalist and ethnic hatreds, as Eric Gabe recounts in his memoirs.Footnote 42 Despite embracing Jesus as Messiah, he and Jewish Christians in the city wanted to show that they still identified and lamented with the rest of the Jewish population in the city.

By 1919 Lev was working with the Baptists (Romanian, Moldavian, and Ukrainian) in the city, who rented Sommerville Hall at 20 Unirii Street, the former Jewish-Christian prayer house of Joseph Rabinovich from the 1880s. The house was placed at Averbuch's disposal without restrictions by the Baptists for his work with the Jewish community.Footnote 43

The Norwegian Israel Missionaries’ description of a Sunday evening service at Averbuch's church confirms the descriptions in the Siguranța reports. They mentioned a ‘full house’ with ‘believers of all nationalities, Russians from the most varied parts, Bulgarians, R[o]manians, a couple of Serbs, and an American missionary couple’.Footnote 44 This diversity troubled authorities seeking to promulgate Romanian ethno-religious culture. Romanian culture was in a development phase and Romanian ethno-religious culture was a fluid concept from the centre in Bucharest to the peripheral borderlands in interwar Romania.Footnote 45 However, for Romania's most influential political, social and religious leaders of the time the definition of ‘pure Romanian culture’ did not include Jews and sectarians. It is important to note that Romanian authorities were relatively untroubled when Hungarians or Germans converted to evangelical faiths, but they worried when Romanians increasingly joined the minority religions. Averbuch's group welcomed anyone into their prayer house, encouraged the use of various languages in services and in publications, and openly spoke against nationalism. They went against what established religion, in this case the Romanian Orthodox Church, encouraged at the time: clear ethnic-religious boundaries.

Upon receiving their appointment to remain in Bessarabia, Averbuch served as pastor of the Baptist Church at 20 Unirii Street in Chișinău in 1918 along with pioneering Russian Baptists Andrei Ivanov and Tihon Hijneacov, joined later by Boris Bușilă.Footnote 46 Hijneacov was mistakenly identified as Jewish by Siguranța agents – ‘preotul evreiesc al sectanților’ [the Jewish priest of the sectarians] – revealing again the association between Jews and evangelicals made by police.Footnote 47 While serving as one of the Baptist pastors, he also continued to work as a representative of the London-based Mildmay Mission to the Jews.

Though Mildmay was not a Baptist organisation, it recognised the Baptist character of Averbuch's community of Jewish evangelical converts as something to encourage, and as they saw it ‘Baptist in those regions stands for true conversion’.Footnote 48 Since evangelicals faced restrictive legislation that often hindered their own activity, the Chișinău Baptists appealed to other mission organisations for help to obtain important documents from the Romanian government. Averbuch was able to obtain a licence to teach across Bessarabia through the help of J.H. Adeney of the Anglican affiliated LSPCJ in Bucharest.Footnote 49

Averbuch and the Baptist congregation, including those Jewish visitors frequenting the mission, remained at 20 Unirii Street in Chișinău until the summer of 1921, when the hall was sold by the family of Joseph Rabinovich as a private residence.Footnote 50 Providing education – literacy, theology, and practical trades – was an important part of their community engagement, so they looked for buildings that would provide the space required for all their activities. Attempts were made to procure a premise that could also serve as a sewing school for Jewish girls, but they were unable obtain the required advance.Footnote 51

Averbuch and the Baptists met at 26 Unirii Street until 1922, with the financial help of Mildmay Mission. At this location they were opposite a police station – convenient for local authorities to keep an eye on them. The Baptists procured a separate building at 2 Gării Street, and the Unirii Street location became the designated Mildmay Mission building where Averbuch held events and organised activities aimed at reaching the Jewish community.Footnote 52

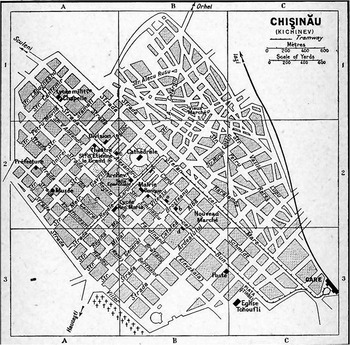

Averbuch's mission building moved several times during the next two decades, reflecting the growth of their community. In October 1922 the name Bethel was chosen for the mission to the Jews branch of the Baptist work led by Averbuch. All subsequent halls rented out with Mildmay funds received the name Bethel, meaning House of God.Footnote 53 This was a popular name among evangelical communities but also familiar to Jewish individuals who recognised it as a reference from the Torah. In 1927, Chișinău city planners changed 26 Unirii to 10 Vladimir Hertza Street, accounting for the change of address in Averbuch's publications and reflecting the changing cultural and political influences in Chișinău (see Figure 1).Footnote 54 In April 1931 they simultaneously acquired a separate location at 73 Haralambie Street specifically for the Jewish Christian believers. This was not a mission hall, but meant for already baptised converts to enjoy a more protected intimate gathering.Footnote 55

Figure 1. Map of Chișinău, 1933.Footnote 60

In 1934 Mildmay left the more central and more expensive Hertza location and rented out 30-b Inzova/Mihai Voevod Street.Footnote 56 Their last listed location was at 90 Gheorghe Lazar/Petropavlovskaia Street in 1937, on the other side of the city.Footnote 57 The moves were due to lack of finances, landlords who wished to sell the property, or tension with police and religious authorities (both BOR and Orthodox Jewish).Footnote 58 Despite the separate locations of the Moldavian/Romanian prayer house and of the Jewish mission hall after 1922, they clearly worked together and assisted or attended each other's services and events throughout most of the interwar period. The Mildmay sponsored hall was particularly aimed at Jews and was intimately linked with the Baptist congregation, composed of ‘Romanians, Moldavians, Bulgarians, Russians, and Germans’, meeting at a different location.Footnote 59

Averbuch was assisted in his work by his wife Maria, as well as by Moise Dreitschman, Nathan Feighin,Footnote 61 Solomon Ostrovsky, Nina and Marcu Tarlev, Isaac TrachtmanFootnote 62 and Wulf Țahan, among others. Apart from the Tarlevs, all were Jewish converts. In 1925 the Ministry of Religious Denominations through Decision 5734 prohibited an ethnic minority individual from leading a majority ethnic Romanian congregation.Footnote 63 This prevented Averbuch (a Jew of Ukrainian nationality) from being the pastor of the Chișinău Baptist church in which the majority were non-Jewish members.Footnote 64 Nevertheless, he continued to preach often at the Baptist church in Chișinău. He based his work at Unirii (Hertza Street), officially within the Mildmay Mission, to avoid difficulties with the authorities.

Though he lost the title of pastor at the Baptist church, Averbuch's responsibilities did not diminish. In fact, the Averbuchs were often overworked and suffered health problems.Footnote 65 They went on furlough from June 1927 to March 1928 to the United States and the United Kingdom, during which time Solomon Ostrovsky, an early convert of Averbuch's from Ukraine, led the activities in Chișinău until their return.Footnote 66 On his return, Averbuch wrote to the leaders of the Romanian Baptist Union in Bucharest, greeting them as his ‘brothers and sisters’, and recounted from his travels that many Jewish people were interested in the person of Jesus. Even with his absence from Chișinău, the meeting hall was packed.Footnote 67

Along with their focus on bringing together Judaism and Christianity, and their continued association with Jewish theology and communities, one of the major sermon themes at Bethel, ‘God is love’, attacked the prominent role of the nation in Romanian society and religion. A Siguranța police agent's sermon notes from September and October 1918 claimed Averbuch preached that nationalism and the national church were against the true law left by Jesus: to love God and to love one's neighbour as oneself.Footnote 68 Averbuch defined ‘neighbour’ as any human being, regardless of nationality. Since nationalism excluded love of ethnic neighbours, he argued it contradicted the precepts of the Bible: ‘God is love, and nationalism is against love thus against God.’ Similar sermons by Averbuch and by others denouncing hatred and differentiation between nationalities were mentioned in police reports as late as 1936.Footnote 69 This teaching clearly reflected their multi-cultural/multi-ethnic congregation, but also made them targets of suspicion by local police and state authorities seeking to create a uniform and predominantly Romanian culture and society. Averbuch, Feighin, Tarlev, and others in the group elevated religious identity over that of the nation.

In late 1928 or early 1929 a ‘Hebrew Christian Community’ was formed separate from both the Romanian/Russian/Ukrainian Baptists and the Mildmay Mission, but still in collaboration with them both. They used the Mildmay building on Hertza Street for religious services but gathered money to fund their own ‘Mishkan’ or ‘Tabernacle’.Footnote 70 The Tabernacle was the place where God was present in Jewish history before the building of the Temple in Jerusalem. Only in 1931 did they manage to rent a separate building that they called Mishkan on Haralambie Street, in what member Eric Gabe referred to as the old part of Chișinău, and closer to the Jewish sector. This may have been geographically more strategic but was also less expensive than a more central location.

The group took the name Hebrew/Jewish Christians of the New Testament and Evangelists (Evreii Creștini Noului Testament și Evangeliștii).Footnote 71 They were thus associating themselves with the theological principles of the Evangelical Baptist Church (Biserica Baptistă Evangeliștilor) also growing in Chișinău under the leadership of Averbuch's former disciple Boris Bușilă. They did this while maintaining their Jewish identity, but also encouraged people of all backgrounds to join their meetings. This mix of ethnicity and religious practices made them suspicious to police but also alluring to the ethnically diverse populations in the borderland region of Bessarabia.

Lev Averbuch, along with Nathan Feighin, Isaac Trachtman, Moise Dreitschman, and Marcu Tarlev, formed the leadership of the new group. On 9 June 1929 Tarlev and Dreitschman were ordained as pastor and deacon respectively of the new Jewish Christian church in Chișinău. The reason for ordaining Tarlev, a Bulgarian, as pastor was perhaps to avoid further complications with the local police. The inaugural ceremony was attended by the president of the Romanian Baptist Union, Constantin Adorian, and his wife, conveying the blessing of the Romanian Union upon their work. As with the previously mentioned multi-lingual services that characterised them, Adorian gave a sermon in Romanian, Averbuch in Russian, and Feighin in Yiddish; songs were also sung in all three languages.Footnote 72

In a letter to the Baptists in Bucharest, Averbuch explained the need for this group to join the recently formed International Hebrew Christian Alliance (IHCA).Footnote 73 The impetus came after Feighin attended an IHCA conference in Hamburg in July 1928.Footnote 74 Joining this international organisation allowed more protection for their congregation in the eyes of the Romanian state authorities and better represented their desire for maintaining their Jewish heritage alongside their new Christian faith. However, the continued Baptist character of Averbuch and Tarlev's congregation was observed by others as well. Leon Levison, president of the IHCA, visited Chișinău in 1929 and 1932 and described it as similar to a Baptist Sunday morning service in Bessarabia where a closed service with communion was held only for baptised members, followed by an open service and a meal ‘agape feast’ for all.Footnote 75

Between 1931 and 1937, the Jewish Christians of Chișinău had two buildings. Bethel (‘House of God’) was the Mildmay mission building with events particularly for the unconverted, while Mishkan (Tabernacle – ‘God's dwelling place’) was the prayer house for baptised Jews and Gentiles.Footnote 76 Other property of the community included an orchard, burial ground, and rest home, providing various services for members. Averbuch was instrumental in regaining the orchard and the burial ground, Machpelah, that belonged to Rabinovich's Israelites of the New Covenant.Footnote 77 A convalescent home called Menuchah was also run by the community. This rest home was set up in conjunction with the Romanian/Moldavian Baptists in 1925, consisting of three rooms, a kitchen, and a bathroom.Footnote 78 Such acquisitions providing support for members in their congregations, as well as for others in need, shows the advanced social networks that the evangelicals had in Chișinău, rivaling other institutions during this period.

Activities and Institutions

As a community they engaged in activities that helped bolster the education of their members, provided them with important social networks, and further reveal the ethno-religious boundary breaking work of Averbuch and his friends. Averbuch and Nathan Feighin taught at the Baptist primary school on Bender Street in the early 1920s.Footnote 79 A school was also run in Bethel for Jewish children, once the Jewish Christians formed their own congregation. This was an opportunity to cater specifically to the Jewish children of Chișinău, who were feeling the growing influence of antisemitism spreading from Romanian administrative institutions.Footnote 80

Feighin offered free Hebrew and Yiddish language courses and tutoring in messianic prophecies from the Tanach. Along with Isaac Trachtman, he daily taught groups of about forty young people to read Yiddish, Russian, and Romanian, using the New Testament as a textbook. The classes were evangelistically driven, beginning and ending with prayer, though the form and content of the prayers is unclear. It was a great draw to locals, who could learn to read for free or could send their children to learn at no expense and in a safe environment where their Jewish ethnicity did not cause marginalisation.Footnote 81

The archival documents, both police reports and denominational newsletters, seem to imply that these schools were separate from the Shabbat and Sunday schools connected to the weekly religious services that took place both prior to and after the formation of a separate Jewish Christian community. By the 1930s the focus of the work moved to the latter – religious teaching from Old and New Testaments in the Shabbat school (conducted in Hebrew and Yiddish) and the Sunday school (likely in Russian). Teaching was done in a rabbinic model similar to the cheder, the traditional Jewish primary school that taught Hebrew and Judaism.Footnote 82 Often up to 100 children would recite Bible verses and sing songs in Hebrew, Yiddish, Ukrainian, Russian, Romanian, and German. During the summer months the work focused on children, providing outings free of charge to the orchard owned by the Jewish Christian community. These events drew in local children, many of whose parents did not attend Averbuch's meetings.Footnote 83

The work among women in the city, both Jewish and Gentile, was led by Russian convert Nina Tarleva, who worked at a primary school before being hired full time by Mildmay.Footnote 84 Her husband, Marcu, became a Mildmay staff member in her place in 1929 due to unspecified ‘changed family circumstances’, the same year he was ordained as pastor of the Jewish Christian Community.Footnote 85 However, Nina continued to organise meetings such as one on 24 February 1935 with eighty women present. Lasting from 7pm to 10pm, women from across the social spectrum shared their faith experiences, revealing not only ethnic, religious, and linguistic diversity but also class diversity. Sophia Cherchez of ‘former Russian nobility’ sang a Jewish and a Russian hymn was followed by a local unnamed market woman who gave her story of coming to faith. Nina also held lantern lectures on women in the Bible.Footnote 86 This technology was a great asset for the community and drew large crowds, especially to Saturday evening lantern lectures.Footnote 87 The visual aspect, projecting images to accompany the Jewish-Christian teachings and sermons, catered to both young and old, and especially to the less literate guests or members of the congregation.

Adult scripture memorisation was also a part of community engagement, whereby the Bible chapter to be read during the week was chosen by Averbuch or Tarlev but the individual chose the verse to memorise and in their preferred language.Footnote 88 The openness with, and fluidity of, languages used reflected the situation in other evangelical congregations across Romania but nowhere does it seem to have been quite as diverse as in Chișinău. The emphasis placed on studying the Bible, both for adults and children, points to the importance of text in these communities.Footnote 89

Though the Bible (the Tanach/Old Testament and the New Testament) was used as the authoritative text, supplemental literature was printed to guide members in their study of it. Their publications also reveal their seemingly radical ideas at the time about religion and their multilingual, multi-ethnic version of Christianity that challenged the nationalism of the established Orthodox church and the state's attempts at religious homogenisation. Between 1920 and 1924 Averbuch edited the periodical The Friend (Prietenul/Друг), publicising it as a religious-moral-literary organ. The editors claimed the publication was meant to be ‘a true friend to all’, regardless of nationality, religious confession, social class or intellectual level, aimed at old and young, men and women, peasant and professor.Footnote 90 Members, even children, distributed Prietenul on the street, near synagogues, in taverns and restaurants across Chișinău.

The publication included songs, poems, and articles about the Christian faith by converted Jews, Romanian and Russian Baptists, and even Orthodox priest Iuliu Scriban and BOR Hierodeacon Dumitru Cornilescu (before he embraced Protestant Christianity). Scriban in turn wrote positively in 1922 of the work Averbuch was doing.Footnote 91 Maria Averbuch also contributed frequently, revealing the increased presence of women as contributors of music and even theological teaching in these evangelical communities.Footnote 92 A newspaper with the same name was edited by the virulent Chișinău antisemite Pavel Krushevan prior to the First World War.Footnote 93 Averbuch deliberately used the same name for his paper to challenge antisemitic attitudes and encourage rapport between Jews and Christians.Footnote 94 However, authorities banned the publication in 1923, for reasons yet unknown, but likely due to the mix of Romanian and Russian (Latin and Cyrillic scripts in the paper).Footnote 95 Romanian censors distrusted publications written in languages they could not read, especially Russian and Hungarian, assuming that such publications were irredentist.Footnote 96

The following year, 1924, he began to edit the bi-monthly The Herald of Good News/Gospel Herald (Binevestitorul/Благовестник/מבשר טוב) in separate issues of Romanian, Russian, and Yiddish.Footnote 97 Among the contributors were Marcu and Nina Tarlev, Romanian Baptist leaders Constantin Adorian and Jean Staneschi, and articles from the well-known Russian evangelical leader Ivan Prokhanov.Footnote 98 Their community began to depend increasingly on this publication due to legislation in 1934 restricting the import of literature from abroad.Footnote 99 Romanian Baptist and Brethren communities distributed Binevestitorul among Jews in their towns and cities. In turn, Averbuch and other Jewish Christians also distributed evangelical publications, particularly during market days and holidays to reach a larger audience.Footnote 100

Literature distribution and colportage was an important part of sharing their beliefs, both in Chișinău and across Bessarabia. Members of Averbuch's group took turns travelling as colporteurs.Footnote 101 They often aggravated police who had trouble keeping track of which groups and literature had passed the censors and what was illegal proselytising. Wulf Țahan from Averbuch's congregation was apprehended by gendarmes in Cimișlia, Tighina county, southern Bessarabia, on 14 June 1934, selling Baptist books without authorisation.Footnote 102 Police confiscated tracts entitled Masena: Un adevărat israelit (Masena: a true Israelite) and Mai poate crede omul de azi in minuni (Can the human of today still believe in miracles?), both published in Bucharest, by LSPCJ and the Baptist Evangelical Society, respectively.Footnote 103 Books such as these reveal the identity struggle between religion, ethnicity, conversion, and assimilation encountered by members of Averbuch's group. They developed new ways of describing their change of faith and their interaction across ethnic and religious divides.

Members, Converts, True Jews

Many of the Chișinău Jewish Christians did not consider themselves to be converts, even though they were baptised by Averbuch or other evangelical pastors. They saw themselves as embracing a purer form of their previous confession. Through baptism they were following the example of Jesus and identifying as his disciples. Since Jesus performed the act of baptism as a Jew and similar acts of cleansing existed in Judaism in the past, they attributed to baptism the symbolism of repentance and return to God cor renewal of their faith in God. This was how they appropriated the theological concepts of metanoia (in Greek) pocăință (in Romanian), teshuva (in Hebrew). All refer to repentance and the need to confess sins, repent, and return to friendship with God. Orthodox Judaism continued to consider them apostates, similarly to how BOR viewed the evangelicals.

As previously mentioned, the conversion of Jews to Christianity is often approached instrumentally, but the fervor for religious reform during the period along with the hostility these ‘sectarians’ faced points to more nuanced motivations for why this group of Jews adopted their own version of Christianity. One of the chief reasons given for their change of beliefs was ‘personal and un-coerced conviction after reading the scriptures’, pointing to the importance of text in these communities and of individual agency in interpreting that text.Footnote 104

Another was a seemingly more egalitarian community among these new faith groups, what one Siguranța report from 1918 called ‘equality of the sexes’. A Jewish woman in Chișinău said she joined the Baptists because they did not consider her unclean: while the synagogue deemed women unworthy, Baptists called them sisters. A Siguranța agent even reported that a majority of Baptist women were Jewish.Footnote 105 However, membership rosters show this was not the case.

From 1918 to 1928, curious Jewish residents came to the Baptist meetings in Chișinău and joined the Baptist congregation if they were baptised.Footnote 106 Candidates would spend a number of weeks studying the Bible beforehand, examining mostly Baptist doctrines dealing with Jesus as the son of God, the Incarnation, the Trinity, and the Law of Moses.Footnote 107 They accepted Yeshua or Jesus's death on the cross as atonement for their sins and his resurrection as providing hope for eternal life in fellowship with God. They held to basic evangelical beliefs of salvation by faith in Jesus alone, the need to be baptised as a public testimony of joining the community, and the need to share the message of the Gospel and one's new faith (evangelisation). Unlike other evangelical denominations, they engaged with rabbinical texts and focused on the elect position of the Jewish people in God's plan of salvation.Footnote 108 After the establishment of a separate Jewish Christian community, those baptised joined either community, often attending services at both. It seems the annual average number of baptisms of Jews in Chișinău was around three, but also included gentiles.Footnote 109

In 1919 Nina Tarleva, siblings Moise and Ida Dreitschman, and Olga, who later became Moise's wife, were baptised. Nina was Russian and previously Orthodox while Olga was German Lutheran.Footnote 110 Engineer Marcu Tarlev was baptised one year after his wife in 1920.Footnote 111 Both Isaac Trachtman and Solomon Ostrovsky joined Averbuch's group in 1921 and Wulf Țahan in 1923.Footnote 112 Feighin, a cantor at his local synagogue, was a secret believer prior to Averbuch's arrival but joined the community publicly after conversations with the latter.Footnote 113 All were baptised in the first years of the Averbuchs’ work in Chișinău. Another influential convert in the city was Moses Richter, baptised by Averbuch on 24 April 1924.Footnote 114

Richter became a missionary for the German Baptist churches in Bucharest and in Cernăuți, the capital of the Bukovina region.Footnote 115 Through him, Eric Gabe, a music student in Bucharest, and his mother Stephany joined the community in Chișinău. Gabe became another of the community's unofficial leaders in its last years before the war.Footnote 116 He attended Bible studies first with Lutherans, and increasingly with Orthodox Reform movement Oastea Domnului members, Tudorists, Baptists, and Brethren. Except for the Lutherans, these groups were all part of the religious reform movements and increasing religious fervour that occured in Romanian interwar society.Footnote 117 An interdenominational attitude after 1929 made the Chișinău community especially attractive to Jewish converts and to others not wanting to join a specific denomination. Their fluidity and movement between religious groups depended on language, music, and the degree to which each local minister welcomed Jewish conversion.Footnote 118

Many recounted that their conversion, their change of heart and of faith convictions, happened within the context of prayer meetings in Chișinău. Praying aloud in public meetings was considered an important first step for new believers.Footnote 120 Averbuch brought others to faith during visits at the Anglican Mission in Bucharest or while he spoke at Baptist meetings, like the wealthy Jewish man with his two children who responded to a call for repentance during the sermon at the twentieth-fifth anniversary celebration of the Chișinău Baptist Church.Footnote 121 Increasingly, children attending the Shabbat and Sunday schools started to seek baptism, having grown up in the community.Footnote 122

The monthly publication Binevestitorul also brought in believers. A Yeshiva student in Transylvania came across an issue of the magazine and started a study group with thirteen other students who came to believe Jesus was Messiah.Footnote 123 Attenders, if not actual converts, included Jewish communists as well.Footnote 124 The number of attendees in Siguranța reports shows that many were attracted to Averbuch's community but were hesitant to approach baptism due to pressure from their previous religious communities or their families.

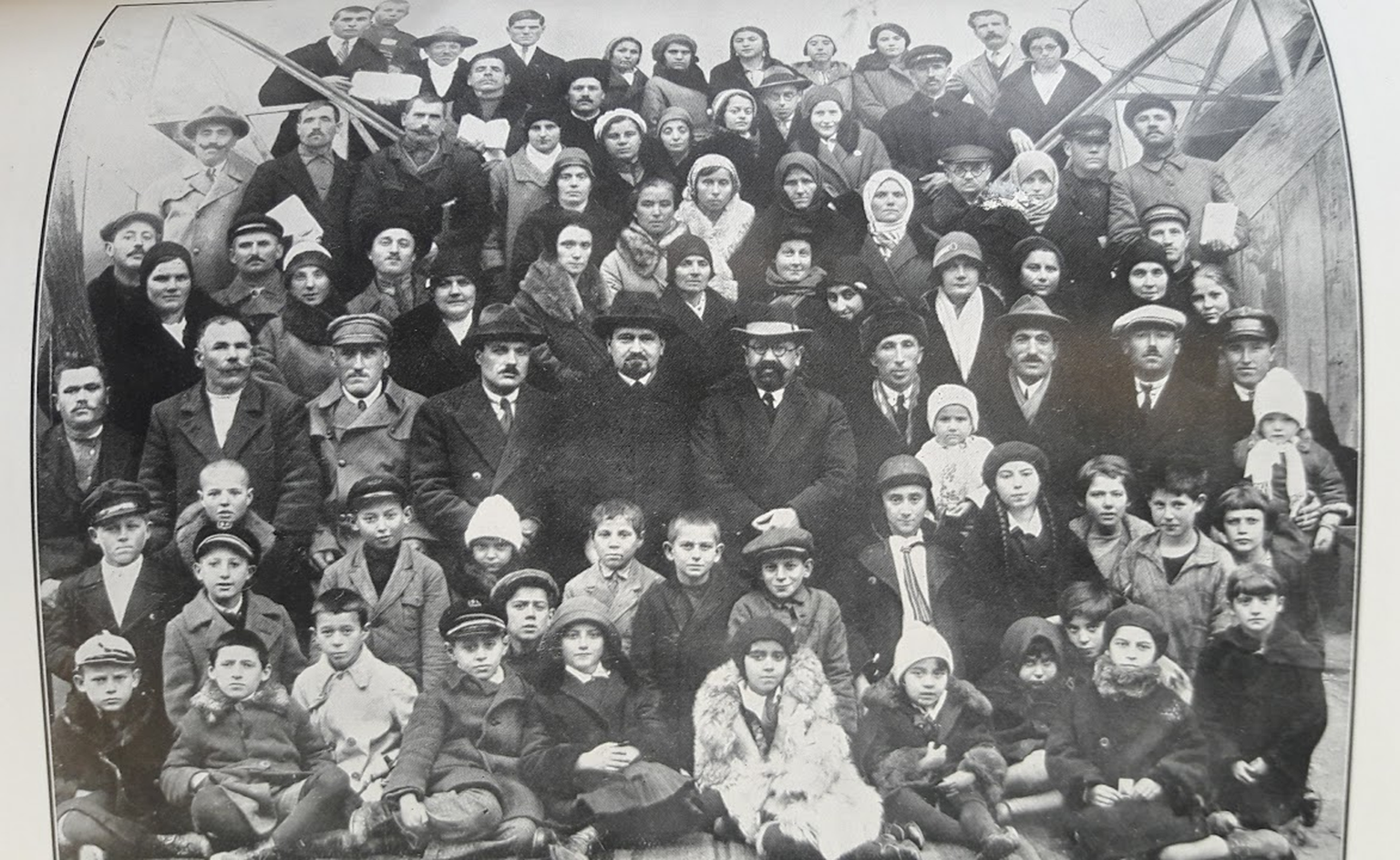

Converts often faced harassment from their families and from the Orthodox Jewish community. The wives of Feighin, Țahan, and of an unnamed member, likely Aron Wulf, were vehemently against their acceptance of Jesus as Messiah. However, Mrs. Feighin and Sura-Lea Țahan were baptised in 1924 and 1927 respectively.Footnote 125 Physical beatings of converts by family members often occurred.Footnote 126 Three young men baptised in 1927 were beaten by relatives, including Abram Chiperșnit whose mother, Ester Rizca, violently interrupted Averbuch's meetings and was only held back by the police she had brought.Footnote 127 The Orthodox Jewish Chief Rabbi Tsirelson of Chișinău also tried to draw back converts from Averbuch's congregation (see Figure 2).Footnote 128 They saw the group for what it was: a challenge to existing religious authority.

Figure 2. Averbuch and his congregation in 1932.Footnote 119

It is unclear if any returned to Orthodox Judaism due to social and familial pressures, but many found a supportive community with the Jewish Christians and with the mixed ethnic background of Averbuch's group in Chișinău as well as with a network of such communities across the country. Leon Schor and Asher Leisersohn were ‘brought to the Lord’ through Moses Richter in Bucharest but were baptised along with non-Jews in Chișinău. Russian and Romanian Baptists were encouraged to show special care for the two new Jewish brothers in Christ, who would not have family to rejoice with them like the other baptismal candidates.Footnote 129 The warm hospitality of the Averbuchs and Tarlevs was another means by which their community grew, as did their consistent contact and friendship over the years.Footnote 130 For example, the first publisher of Averbuch's Prietenul in 1919 went bankrupt, but the Tarlevs kept in contact with him throughout the interwar years and, at the age of 73, the elderly man also came to accept Yeshua/Jesus as the Messiah.Footnote 131

With the growing hostility towards Jews it is interesting that the community records the baptism into their community in 1937 of a young former Legionary member (of the Romanian fascist organisation Legion of the Archangel Michael). The man complemented his conversion account with a duet alongside Trachtman and a solo in Yiddish.Footnote 132 A police report identified that in Chișinău, as in other parts of the country, Romanians joined the Baptists and later the Jewish Christians because BOR priests were thought to keep Bible interpretation for themselves.Footnote 133 By contrast, Averbuch was seen as helping his congregation understand the Bible. This neglect by their local BOR priests was a reoccurring reason given in statements to the police by former Orthodox church members who joined these new confessions in Romania and who in Chișinău were often first drawn to the community by the various holiday services.Footnote 134

The most well documented events of Averbuch's community were the Jewish and Christian holidays, such as Rosh Hashanah, Purim, Pesach/Passover, Easter, Chanukah, and in particular Christmas. Leaders of the community capitalised on the opportunity holidays gave to make their presence more visible (or more audible) in the city. Meetings for these festive days were especially crowded with more visitors than usual eager to observe and participate in the rich musical repertoire and the unique blend of Jewish and Christian teaching, as well as to see the ‘magic lantern’ projector.

For example, Rosh Hashanah in their first year in Chișinău was already attended by many Jews, reported Averbuch.Footnote 135 Sermon themes for this holiday in particular often dealt with rejecting ‘worldly’ celebrations of holidays (such as drinking alcohol) and argued that Jesus as Messiah brought forgiveness from sin, not the rituals prescribed by rabbis. In 1936, they celebrated Rosh Hashanah at the new location for Mishkan (the Tabernacle of the Jewish Christian Community), where many in the audience were observant Jewish parents whose children attended Averbuch's Shabbat school.Footnote 136 Though the parents did not join the eclectic group, they still respected Averbuch for what he was providing for the children in Chișinău.

Of Mixed Repute

Averbuch had a mixed reputation in Chișinău: respected and loved by some while hated and feared by others. His attention to social issues allowed him to break barriers in Jewish and Romanian, Russian and Ukrainian circles.Footnote 137 He collaborated with prominent Jewish individuals in the city to find cases of social need and as part of the Baptist Union Board in Bessarabia, he helped administer funds received from abroad for those suffering from famine in 1926.Footnote 138 He was also involved in prison ministry, where the chief of the local prison allowed Averbuch to form a choir and organise Sunday school classes, even encouraging him to open a library in the prison, funded through entrance fees from public meetings.Footnote 139 Though prison ministry is seldom mentioned in the missionary or police reports, Averbuch visited prisons even in Iași in 1927 where a Polish-Jewish prisoner revealed he came to his new faith through a Baptist preacher imprisoned for spreading ‘sectarian propaganda’ and through a poem by Maria Averbuch he read in a copy of Binevestitorul.Footnote 140

Though he was considered an apostate, good rapport seemed to exist between Averbuch and the majority of Jews in Chișinău. He rented a seat in the great synagogue, relinquished to him by a doctor friend, Abramov, with the approval of the synagogue authorities. Occasionally joined by Tarlev or Trachtman, he always brought along the Christian Bible in Hebrew as well as evangelistic tracts when attending the synagogue. Theological disputes inevitably arose as Averbuch insisted on sharing his interpretation of the Jewish scriptures, but these remained cordial.Footnote 141

During conversations about Jesus at the Chișinău Zionist synagogue Averbuch reported that Jewish worshippers claimed, ‘If a missionary had come into a synagogue 25 years ago and spoken like this, he would have been beaten to death; but we love Mr. A[v]erbuch and listen to him with pleasure.’Footnote 142 He seemed to find friends across the spectrum of religious Judaism, both in Chișinău and across Bessarabia. While holding meetings at the Baptist hall in Reni he stayed at the home of the local rabbi, whose daughter in Chișinău wrote favourably about Averbuch.Footnote 143 Not only did Averbuch visit synagogues, but the Chișinău synagogue choir sang at Bethel in 1937.Footnote 144 However, some Jews were afraid to come to Bethel or to visit Averbuch outside the Jewish quarter. A rabbi from Transylvania, leader in the Mizrachi movement (the Orthodox branch of the Zionist movement), visited Chișinău and thought Bethel was a synagogue, but after conversations with Averbuch was afraid to enter further than the lobby where he found crosses displayed. He accepted a New Testament and invited Averbuch to visit him in Transylvania.Footnote 145

Opposition too was not uncommon. Unser Tsayt, a Chișinău Yiddish newspaper, published a warning in 1927 after a Sabbath evening meeting at Bethel: ‘One by one and in groups children are being deceived, old and young are being misled . . . Jewish souls are being caught.’Footnote 146 In Călărași, Trachtman was physically threatened by Jewish leaders, while in Căușeni ‘fanatical Jews’ followed him, telling people not to buy his literature. He recounted the openness of Jewish gendarmes and atheist tailors, pointing to hostility occurring mostly among Orthodox religious Jews. Trachtman, Averbuch, and the others believed their group extremely relevant to Greater Romania's increasingly modernising society by emphasising the interest for their message among assimilated and ‘modern’ Jews, while it was rejected by Jews they considered more backward or religiously ‘fanatic’.Footnote 147 They intentionally sought to distance themselves from the latter in the eyes of the wider Chișinău public, who may have also considered Averbuch's group fanatic due to its persistent proselytising, a common trait of evangelical communities.

The Jewish owner of a newsstand often reported the Jewish Christians to the police, despite the fact that they possessed the necessary licence to distribute literature.Footnote 148 Averbuch's name itself could evoke resentment, revealing he was relatively well known in the Jewish communities of Bessarabia.Footnote 149 In the Ismail synagogue he had a heated debate with the ritual slaughterer who, nevertheless, wished him success ‘only among the goyim’. Following this encounter Chief Rabbi Tsirelson printed an announcement in the Jewish weekly Săptămâna that no synagogues should allow Averbuch to preach.Footnote 150 Yet, according to Gabe's memoirs, when non-Jewish opponents tried to publish against Averbuch, certain Jewish editors refused to print it.Footnote 151 There was therefore a mix of reactions among the different Jewish groups in Chișinău to Averbuch and his group.

The local authorities were surprisingly helpful, though the Romanian bureaucracy and changing laws on religion by the Ministry of Religious Denominations made their work difficult. The Mayor of Chișinău gained permission for Averbuch to hold meetings in public halls, theatres, and the university. In Chilia-Nouă, the gendarme chief advised Averbuch to rent out the largest hall in town for two evenings because the Baptist prayer house was too small and difficult to reach.Footnote 152 However, renewing his authorisation to preach was sometimes required every three months, entailing time-consuming paperwork, trips to Bucharest, and fees.Footnote 153 They were also not strangers to the Romanian judicial system. Feighin, Tarlev, Trachtman, Țahan, and Averbuch were brought to court various times for distribution of literature or disturbing the peace, but the judges acquitted them and sometimes even requested Bibles.Footnote 154 The authorities ensured policemen were always at the gatherings to keep order.Footnote 155 Police misconceptions in reports also reveal a suspicious attitude toward the Chișinău Jewish Christians, often accusing them of treasonous ‘sectarian’ or ‘bolshevik’ ideas of universal brotherhood and anti-nationalism.Footnote 156

In evangelical circles, Averbuch was considered a talented preacher and theologian. He spoke at Baptist churches across Bessarabia and eastern Romania at the request of local Romanian and Ukrainian or Russian pastors.Footnote 157 In 1929, Averbuch took part in a three-member committee organised by the Baptist industrialist Adam Sezonov to convince Ioan Bododea, the former pastor of the Baptist Church in Brăila, to see the error in embracing Pentecostal theology. Though unsuccessful, Averbuch published subsequent polemical articles against Pentecostals.Footnote 158 Despite a period of disagreement and tension between Averbuch and the Chișinău Baptists from 1930 to 1934, the reason for which is unclear, ties resumed, and congregants participated in each other's services.

At the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Baptist Church in Chișinău, Averbuch was among the speakers, and many from his congregation attended.Footnote 159 When the Bucharest German Baptist Church celebrated its eightieth anniversary in May 1936, Averbuch was again one of the speakers. Averbuch delivered the main sermon, bringing greetings from his ‘Jewish Baptist Church’ in Chișinău and from all Russian Bessarabian Baptist Churches (‘Judenchristliche Baptistengemeinde und die russischen Baptisten Bessarabiens’).Footnote 160

Romanian Baptist editors printed a letter he wrote addressing the antisemitic elements among gentile believers and their hostility towards Jewish Christian believers. ‘Let this not be the case among brothers and sisters in Romania – let us strive to love one another following the example of our Lord Jesus Christ. Then the Jews and the whole world will recognise us as His true disciples,’ wrote Averbuch. The letter encouraged Romanian Baptists to recognise and to stop the creeping influence of antisemitism in their churches. He showed his bond with them by signing himself ‘your youngest brother in Christ’ (‘Cel mai mic frate in Christos’).Footnote 161

The sustained collaboration with Baptists led Grigore Comșa, the BOR Bishop of Arad in Transylvania, to write a scathing article against Averbuch, whom he called the ‘leader of the Baptist movement’ in Bessarabia. Comșa falsely accused him of spreading the Baptist faith to Romanians to make them forsake their ancestral law, while he continued to keep the Jewish law.Footnote 162 According to Averbuch, another virulent antisemitic BOR priest in Chișinău, whose name was not given, published a paper in Russian and Romanian inciting people to violence, claiming that Jesus recognised the Jews as ‘a wicked people, children of the devil, and scorpions'. However, on attending an Easter service at Bethel, Averbuch related his own conversion account, analysed Romans 11 with the priest regarding the place of Jews in the history of God's rescue plan for humanity, and discussed what harm the priest's actions were doing to the cause of spreading the Christian faith. Averbuch claimed this resulted in the priest's change of heart.Footnote 163

BOR Archimandrite Iuliu Scriban appreciated Averbuch's work in the early 1920s, especially Averbuch's arguments against national Judaism.Footnote 164 Averbuch preached against Zionism as the answer to the plight of European Jews and instead advocated mutual co-existence. This again reflected the unique mixed population of his congregation and their teachings against various types of nationalism.

Conclusion

Eric Gabe described Averbuch in his memoirs as blunt, strict, and uncompromising in his morals, alienating some he worked with, but that he had a deep desire to serve his fellow humans spurred by his convictions regarding the teachings and identity of the Jewish rabbi Jesus, or Yeshua as Averbuch called him.Footnote 165 In July 1937, Mildmay surprisingly printed that they lost the services of Averbuch and that there were serious setbacks in Chișinău.Footnote 166 Once Mildmay claimed Averbuch's work in Chișinău to be unparalleled in blessing, but now referred to it as a considerable expense.Footnote 167 In August 1937, Mildmay closed down their mission in Chișinău, releasing Tarlev and Trachtman from their staff.Footnote 168 The latter, along with Samuel Ordinsky and Wulf Țahan, continued to lead the congregation of Jewish Christians and other ethnic members, but Averbuch left Chișinău for London at the invitation of Isaac Davidson, director of the Christian missionary organisation Barbican Mission to the Jews.

Other sources reveal misunderstanding and slander as reasons for the Averbuchs’ relocation.Footnote 169 In a letter to the Swedish Israel Mission Averbuch claimed he could not return to Romania in 1937 because the Romanian authorities refused to reissue him a Nansen pass.Footnote 170 Averbuch also took a fall in April 1937 that caused internal injuries and initiated the steady decline of his health until his death in July 1941.Footnote 171 He was buried in Abney Park Cemetery at Stoke Newington in North London. His tombstone reads: גואלי חי [My redeemer lives], a reference to Job 19:25, a Tanach messianic prophecy in Christian theology pointing to Jesus.Footnote 172 Maria Averbuch died in London on 3 February 1946.Footnote 173

Gabe and Tarlev managed to visit Averbuch in England in June 1939. Gabe remained in London, eventually becoming an Anglican minister, and Tarlev returned to his family in Chișinău to continue pastoring the congregation there.Footnote 174 Unfortunately, the war would almost completely wipe out this unique multi-ethnic, multi-lingual community that crossed so many religious, ethnic and linguistic boundaries, including gender and class barriers. Today, however, there exists a Messianic congregation in Chișinău led by Rabbi Shimon Pozdirca, which consider themselves the spiritual descendants of Averbuch's group, composed of Jewish and gentile believers.Footnote 175

In the Russian context, historian Ellie Schainker identifies ‘serial converts’ who took confessional choice to an extreme and ‘Jews who found the means not so much to be Russian [or Romanian] but to make a positive status change that was still familiar, accessible, and local’.Footnote 176 Such was the case for the Jewish Christians of Chișinău and the gentile members of their evangelical congregation. Inspired and spurred by, but also contributing to, the growth of evangelical groups in Romania, Lev Averbuch and the others created a unique community that challenged the ethnic-religious boundaries in society. While honouring their Jewish heritage and pointing to the Jewish roots of Christianity through their activities and theology, they simultaneously criticised nationalism and antisemitism in Romania and across Europe from the precarious position of being both Jewish and ‘sectarian’ evangelicals.