Nutrition education programmes are designed to improve nutrition knowledge, with the aim of supporting sound dietary intake within the community or a specific target population( Reference Lee, Lee and Kim 1 – Reference Heaney, O'Connor and Michael 4 ). Nutrition education is widespread, with schools, government and health promotion agencies delivering a range of messages that incorporate a nutrition component( Reference Worsley 5 ). Members of the community in most industrialised countries are exposed to education about dietary guidelines or core food group intake. Specific education to prevent or manage lifestyle diseases such as diabetes, CVD or cancer is also widely available( 6 – 8 ). Despite the wide scope of nutrition education initiatives, it is somewhat surprising that relatively few studies have evaluated the level of nutrition knowledge in the general community or other specific group samples, and that the impact of nutrition knowledge on dietary intake is still largely unexplored.

Numerous factors including taste, convenience, food cost or security and cultural or religious beliefs influence dietary intake( Reference Heaney, O'Connor and Michael 4 , Reference Hendrie, Coveney and Cox 9 – Reference Parmenter, Waller and Wardle 12 ). Factors that are well known to influence nutrition knowledge include age, sex, level of education and socio-economic status( Reference Parmenter, Waller and Wardle 12 ). Women tend to have higher levels of nutrition knowledge than men, and this difference has been attributed to their more dominant role in food purchasing and preparation or a lower interest in nutrition by men( Reference Hendrie, Coveney and Cox 9 , Reference Wardle, Parmenter and Waller 11 , Reference Parmenter, Waller and Wardle 12 ). Higher levels of nutrition knowledge have been reported in those with higher education or socio-economic status( Reference Worsley 5 , Reference Dallongeville, Marecaux and Cottel 10 , Reference Parmenter, Waller and Wardle 12 ) and greater levels of nutrition knowledge have been typically found in middle-aged as opposed to younger or older persons( Reference Heaney, O'Connor and Michael 4 , Reference Hendrie, Coveney and Cox 9 , Reference Parmenter, Waller and Wardle 12 ). These demographic factors also influence dietary intake( Reference Wardle, Parmenter and Waller 11 ). The specific contribution of nutrition knowledge to the overall quality of food intake is considered to be complex and is influenced by the interaction of many demographic and environmental factors( Reference Wardle, Parmenter and Waller 11 ). However, greater understanding of the relationship between nutrition knowledge and dietary intake is important as emerging evidence supports a strong link between low health literacy, poor management of chronic disease and increased health costs( Reference Eichler, Wieser and Brügger 13 , Reference Vernon, Trujillo and Rosenbaum 14 ). Although nutrition knowledge is one component of health literacy, it is a central factor as poor dietary intake is strongly linked to all of the major lifestyle diseases and in industrialised countries, it accounts for the majority of health costs( Reference Roberts and Barnard 15 – Reference Harris and Wallace 17 ).

Measurement of nutrition knowledge is challenging( Reference Parmenter, Waller and Wardle 12 ). Most studies have used written questionnaires, but many of these have inadequate or no validation. Responses rely heavily on participant literacy, and this is more limited with lower levels of education and socio-economic status( Reference Adams, Appleton and Hill 18 ). Types of nutrition knowledge assessed also vary widely across instruments, with some measuring general concepts( Reference Parmenter and Wardle 19 – Reference Eppright, Fox and Fryer 23 ) while others explore only some nutrition aspects such as fat( Reference Block, Gillespie and Rosenbaum 24 – Reference Kristal, Bowen and Curry 27 ) or fibre( Reference Block, Gillespie and Rosenbaum 24 , Reference Lee, Godwin and Tsui 25 ). Knowledge of nutrition facts, or declarative knowledge may not translate through to skill or process knowledge, essentially the ability to choose healthier foods, understand food labels or select healthier options from a range of foods available. Nutrition knowledge instruments that assess declarative nutrition concepts may have little relevance to the set of knowledge and skills required to make appropriate dietary decisions that promote health. Zoellner et al. ( Reference Zoellner, Connell and Bounds 28 ) have more recently used the term ‘nutrition literacy’ rather than nutrition knowledge and defined this as ‘the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand nutrition information and skills needed in order to make appropriate nutrition decisions’. This definition focuses on possession of nutrition knowledge and skills that have practical relevance to dietary choices.

As with nutrition knowledge, dietary intake is also difficult to measure, particularly in samples that are large and powerful enough to find significant associations between these variables. Use of dietary records significantly adds to the burden of respondents and researchers( Reference Penn, Boeing and Boushey 29 ), and examination of micronutrients requires more than a few days or a week( Reference Nelson, Black and Morris 30 ). FFQ are the most efficient, cost-effective and practical method for the large-scale measurement of dietary intake, which also includes the measurement of micronutrients( Reference Penn, Boeing and Boushey 29 , Reference Caballero, Allen and Prentice 31 ). However, this method has limitations with accuracy( Reference Caballero, Allen and Prentice 31 ). Interview or recall methods, particularly 24 h multiple-pass recalls, are now used as a method of choice in large population-based surveys( Reference Rutishauser 32 ). Unfortunately, this method is resource-intensive. More recently, dietary intakes typically obtained from FFQ or 24 h recall data have been used to calculate a diet quality score or index that provides an evaluation of the consistency of food intakes with dietary guidelines rather than comparing with nutrient reference values( Reference Collins, Young and Hodge 33 , Reference Guenther, Reedy and Krebs-Smith 34 ). Individuals with high energy intakes may easily meet nutrient reference values yet not consume diets consistent with dietary guidelines( Reference Heaney, O'Connor and Gifford 35 ). Diet quality scores or indices may therefore be a useful tool for investigating the relationship between nutrition knowledge and dietary intake.

As diet is the cornerstone for maintaining health and also for the management and prevention of a wide range of medical conditions( 6 – 8 ), an understanding of the level of nutrition knowledge and its association with dietary intake is paramount. Although factors outside nutrition knowledge including food security and availability( Reference Heaney, O'Connor and Michael 4 ), skills in cooking and food preparation( Reference Parmenter, Waller and Wardle 12 ) through to motivation to embrace a healthy eating style( Reference Worsley 5 ) influence the ability to ‘operationalise’ nutrition knowledge into a healthy diet, some nutrition knowledge is necessary. One must know before one can do. As much of the sustained effort in nutrition promotion revolves around improving knowledge of nutrition through dietary guidelines, and healthy eating guides (e.g. MyPlate)( Reference Britten, Marcoe and Yamini 36 ), the specific influence of nutrition knowledge on dietary intake is an important research question.

In two existing systematic reviews, the relationship between nutrition knowledge and dietary intake has been examined( Reference Heaney, O'Connor and Michael 4 , Reference Axelson, Federline and Brinberg 37 ). The first review( Reference Axelson, Federline and Brinberg 37 ), published in 1985, was informed by a limited number of studies (n 9). Most of the included articles (n 6/9) used the same item test bank( Reference Eppright, Fox and Fryer 23 ) (or an adapted version) to assess nutrition knowledge and reasonably similar methodology, so meta-analysis was possible. This review reported a weak, positive relationship (r< 0·2) between nutrition knowledge and dietary intake (P< 0·01). Although six of the nine studies reported no significant correlation, the direction of the relationship was consistent and significant via meta-analysis. A more recent systematic review on this topic only included studies in athletes( Reference Heaney, O'Connor and Michael 4 ) and due to study heterogeneity, a meta-analysis was not conducted. However, the majority of the studies reported a weak, positive association (r< 0·44) between nutrition knowledge and dietary intake. As a comprehensive and contemporary review of this topic has not been undertaken for some time, the aim of the present study was to systematically review existing evidence from studies investigating the relationship between nutrition knowledge and dietary intake across all populations.

Methods

Search strategy

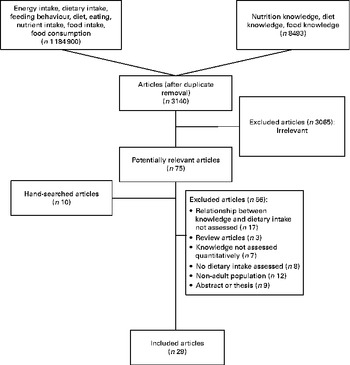

A systematic search using the terms nutrition knowledge, diet knowledge or food knowledge and energy intake, feeding behaviour, diet, eating, nutrient intake, food intake and food consumption was conducted by one researcher (I. S.) from the earliest record until November 2012. The databases included SCOPUS, MEDLINE (OvidSP), SPORTDiscus (EBSCO), Web of Science, CINAHL (EBSCO), ScienceDirect, AMED (OvidSP) and AUSportMed (Informit Online). A hand search of the reference lists of the included articles was conducted to find additional studies missed by database searching.

Eligibility criteria

Original research studies (including randomised controlled trials and cross-sectional and quasi-experimental designs) conducted in adult (mean age ≥ 18 years) human participants and published in a peer-reviewed journal were included for review. Abstracts, reviews, reports and theses were excluded. Studies in all population groups and written in any language were included. Studies were required to use an instrument that provided a quantitative assessment of nutrition knowledge via the report of a participant score. A quantitative assessment for dietary intake was also required, but this could be expressed as either intake of one or more nutrients (e.g. g, mg, μg or percentage of energy), consumption of servings of some or all core foods or a diet quality score or index. Articles were also required to examine the association between nutrition knowledge and dietary intake using statistical analysis. Instruments used for the assessment of either nutrition knowledge or dietary intake did not need to be validated.

Selection of studies and data extraction

After removal of duplicates, irrelevant articles were eliminated on the basis of title and abstract by one reviewer (I. S.). The full text of relevant articles was screened using the inclusion criteria by two reviewers (I. S. and C. B.) (Fig. 1), and data were independently extracted by two reviewers (I. S. and C. K.). Information retrieved included participant and study characteristics (sex, age, population, sample size, country and sampling method), details on the instruments used to assess nutrition knowledge (number and type of items, instrument design, response formats, general or specific knowledge measured, and validation) (Tables 1, 2 and 4) and type and validity of dietary assessment conducted (Table 3). Outcomes of statistical analysis assessing the association between nutrition knowledge and dietary intake were also extracted (Table 3). Disagreements arising from decisions around article exclusion or inclusion or extraction of data were resolved by discussion with a third researcher (H. O.). Studies were deemed too heterogeneous for the data to be pooled for meta-analysis, specifically with respect to instruments and/or approaches used to collect nutrition knowledge and dietary intake data( Reference Liberati, Altman and Tetzlaff 38 ).

Fig. 1 Flow chart showing the selection of studies.

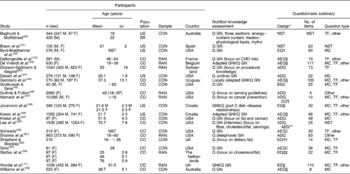

Table 1 Nutrition knowledge in community populations (Mean values and standard deviations)

M, male; F, female; US, university students; CON, convenience; Q, questionnaire; GN, general nutrition knowledge; NST, not stated; TF, true/false; other, open-ended questions; SR, military service recruits; EQ, existing questionnaire; MC, multiple choice; CO, community; RAN, random; AEQ, adapted existing questionnaire; GNKQ, general nutrition knowledge questionnaire; ADQ, author-designed questionnaire.

* Validation of the instruments is detailed in Table 4.

† Byrd-Bredbenner( Reference Byrd-Bredbenner 22 ).

‡ Questionnaire of the Preventive Medicine Centre at the Pasteur Institute of Lille.

§ Parmenter & Wardle( Reference Parmenter and Wardle 19 ).

∥ Eppright et al. ( Reference Eppright, Fox and Fryer 23 ).

¶ Cotugna et al. ( Reference Cotugna, Subar and Heimendinger 80 ).

** US Department of Agriculture Diet and Health Knowledge Survey.

†† Ruddell( 26 ).

‡‡ Paas et al. ( Reference Paas, Scheijder and Wedel 81 ).

Table 2 Nutrition knowledge in athletic populations (Mean values and standard deviations)

F, female; PW, postmenopausal women; CON, convenience; Q, questionnaire; GN, general nutrition knowledge; AEQ, adapted existing questionnaire; TF, true/false; AT, athletes; US, university students; M, male; EQ, existing questionnaire; MC, multiple choice; SN, sport nutrition knowledge; NST, not stated; ADQ, author-designed questionnaire.

* Validation of the instruments is detailed in Table 4.

† Annable( 82 ).

‡ Woolcott et al. ( Reference Woolcott, Kawash and Sabry 83 ).

§ Barr( Reference Barr 84 ).

∥ Jonnalagadda et al. ( Reference Jonnalagadda, Rosenbloom and Skinner 85 ) and Zawila et al. ( Reference Zawila, Steib and Hoogenboom 86 ).

¶ Werblow et al. ( Reference Werblow, Fox and Henneman 61 ).

Table 3 Association between nutrition knowledge and dietary intake

EQ, existing questionnaire; VAL, validated; DR, dietary record; NA, not applicable; +, positive; − , negative; ADQ, author-designed questionnaire; NVAL, not validated; NST, not stated; PVAL, partly validated; USDA, US Department of Agriculture; AEQ, adapted existing questionnaire; DKI, diet knowledge index; DINE, Dietary Instrument for Nutrition Education.

* Relevant to studies using questionnaires or checklists to assess dietary intake not for DR or 24 h recall.

† Baghurst & McMichael( Reference Baghurst and McMichael 87 ).

‡ Pynaert et al. ( Reference Pynaert, Matthys and De Bacquer 88 ).

§ Block et al. ( Reference Block, Gillespie and Rosenbaum 24 ).

∥ Block et al. ( Reference Block, Hartman and Naughton 89 ).

¶ Kaic-Rac & Antonic( Reference Kaic-Rak and Antonic 90 ) and Kulieri( Reference Kulier 91 ).

** Baumgartner et al. ( Reference Baumgartner, Gilliland and Nicholson 92 ) and McPherson et al. ( Reference McPherson, Kohl and Garcia 93 ).

†† Shepherd & Stockley( Reference Shepherd and Stockley 94 ).

‡‡ Feunekes et al. ( Reference Feunekes, Van Staveren and De Vries 95 ).

§§ Roe et al. ( Reference Roe, Strong and Whiteside 63 ).

∥∥ Rockett et al. ( Reference Rockett, Breitenbach and Frazier 96 ).

¶¶ Cho & Fryer( Reference Cho and Fryer 97 ).

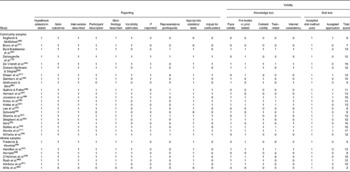

Study quality

Study quality was independently assessed by two researchers (I. S. and C. K.) using a modified version of the Downs and Black scale( Reference Downs and Black 39 ) (Table 4). The original scale consists of twenty-seven items that examine data reporting, statistical power, and external and internal validity (including bias and confounding). Of the twenty-seven original criteria, only eleven logically applied to the study designs included in the present review. Items specific to controlled/intervention trials (item numbers 5, 8, 9, 12–17, 19, 21–24, 26 and 27) were excluded because none of the identified articles had a randomised controlled design. Item 20 that probed the accuracy and validity of main outcome measures was expanded to more rigorously evaluate the quality of the validation of instruments or approaches used to assess nutrition knowledge and dietary intake. This resulted in a maximum possible score of 17 points.

Table 4 Quality ratings

Validity of nutrition knowledge instruments used in the included studies was assessed according to five domains known to be central to the development of a sound and reliable instrument: face validity; pre- or pilot testing; content validity (review or evaluation of the instrument by experts); test–retest validity; internal consistency (intra-class correlation and/or Cronbach's α). One point was awarded for evidence of reasonable and appropriate application of each method of validation. Validity of the dietary intake assessment was based not only on the use of an accepted method for collection of dietary information (e.g. dietary record, FFQ, 24 h recall, diet quality score), but also on appropriate application of the methodology (e.g. methodology was valid for the sample size and population demography used, sufficient days or detail of intake obtained was appropriate to quantify the outcome reported and in the case of questionnaire-based methods such as FFQ or diet checklists, whether the instrument used was validated). A maximum score of 2 points was awarded for dietary intake assessment, 1 point for choice of an accepted method and 1 point for appropriate application. Disagreements were discussed with a third researcher (H. O.) until resolved.

Results

Identification and selection of studies

The initial search netted 1 193 393 potentially relevant articles. After removal of duplicates and elimination of papers based on exclusion criteria, twenty-nine articles were included for review (Fig. 1). Most articles were written in English (twenty-seven of twenty-nine). Of the twenty-nine articles included for assessment, twenty-two were conducted in community populations (Table 1) and seven in athletic populations (Table 2).

Study characteristics

Community populations

Of the twenty-two studies( Reference Dallongeville, Marecaux and Cottel 10 , Reference Wardle, Parmenter and Waller 11 , Reference Dickson-Spillmann and Siegrist 20 , Reference Dissen, Policastro and Quick 21 , Reference Lee, Godwin and Tsui 25 , Reference Kristal, Bowen and Curry 27 , Reference Baghurst and McMichael 40 – Reference Williams, Campbell and Abbott 55 ) conducted in community samples, sixteen assessed participants from the general community and six examined university student populations (Table 1). Half (n 11) of the studies were published after the year 2000. Participant numbers ranged from 40 to 10 286. Most (n 13) were in mixed-sex samples with four conducted only in women and one only in men; one article failed to identify the sex of the participants. Women represented the majority of participants measured (77 v. 23 %), although not all studies provided detail on the sex distribution. Age ranged from 18 to 97 years with seven of the studies reporting a mean age ≥ 50 years. Most studies were conducted in either the USA (n 10) or Europe (n 9) with the remainder from Australia (n 2) and South America (n 1). Only eight of the twenty-two studies used random sampling methods with the remainder conducted in convenience samples. There was limited representation of participants with low socio-economic status, and some studies failed to report this demographic characteristic.

Nutrition knowledge was measured with a written questionnaire for eighteen of the twenty-two studies, one study used Internet-based collection and the remainder were by interview (n 3). The instruments mostly probed general nutrition concepts including knowledge of dietary guidelines, sources and functions of nutrients, skill in choosing healthier foods and nutrition myths. A smaller number measured knowledge of specific nutrition areas including nutrition for cancer prevention (n 2), sources of dietary fat (n 4), diet–disease relationships (n 1) or CHD risk (n 1). The number of items contained within the instruments varied widely from four to 111. Response formats included true or false, multiple choice, open-ended items and ranking scales of statements ranging from agree to disagree.

Athletic populations

Of the twenty-nine included articles, seven studies( Reference Frederick and Hawkins 56 – Reference Wiita, Stombaugh and Buch 62 ) utilised an athletic population ranging from elite to recreational athletes. Most studies were conducted between 1990 and 1995, with one study conducted before 1990 and one after the year 2000. Participant numbers in each study ranged from fourteen to 122 and age ranged from 17 to 28 years; however, one study included a control sample with participants aged up to 65 years. Of the seven studies, one used only male participants, three used only female participants and three used a mixed-sex population. Of these studies, five were conducted in North America and two in New Zealand.

All studies used convenience samples either of mixed sports (n 2) or specific sports (including basketball (n 1), track (n 2) and distance running (n 2)). All studies used written questionnaires and item number ranged from 10 to 87. The instruments all probed general nutrition knowledge and most (n 6) also included items on sports-specific knowledge. Response formats utilised true or false, multiple choice and open-ended items.

Measurement of dietary intake and association with nutrition knowledge

Most studies used an FFQ to assess dietary intake (n 14). Other studies used dietary records (n 9), 24 h recall (n 4), an (adapted) existing food pattern questionnaire (n 2)( Reference Werblow, Fox and Henneman 61 , Reference Roe, Strong and Whiteside 63 ), an author-designed food pattern questionnaire (n 2)( Reference Schwartz 50 , Reference Hamilton, Thomson and Hopkins 57 ) or a fat and fibre screener (n 1)( Reference Block, Gillespie and Rosenbaum 24 ). However, three studies used a combination of these methods( Reference Kristal, Bowen and Curry 27 , Reference Guthrie and Fulton 46 , Reference Frederick and Hawkins 56 ). Some studies only probed certain nutrients (e.g. fat, fibre or Ca), food groups (vegetables or fruit) or general eating patterns (Table 3). Most studies reported some significant, positive association between nutrition knowledge and dietary intake or pattern. Only ten studies reported no significant relationship (Table 3). The associations were generally weak (r< 0·5) and most often, studies reported a positive relationship between higher nutrition knowledge and a greater intake of vegetables (n 11) and fruit (n 10) and a lower intake of fat (n 7). Significant positive associations were found between higher nutrition knowledge and a greater intake of cereals or fish, a lower intake of sweetened drinks, a higher intake of fibre or Ca intake and a higher consumption of some core food groups more consistent with public health guidelines (Table 3). When comparing the community with athlete groups, five of the seven athlete studies (71·4 %) found a positive association between nutrition knowledge and dietary intake, whereas within the community studies, fourteen of the twenty-two studies (63·6 %) found some positive association with eight reporting no significant association. Relatively few studies (n 5) reported a positive association between nutrition knowledge and a negative dietary attribute.

Study quality and validation

Studies scored a mean of 11·2 out of 17 points (range 2–17; Table 4). The mean score for study reporting quality, overall validity of design and data analysis was 7·4 out of 10 points (range 1–10). The validity of nutrition knowledge instruments scored a mean of 2·5 out of 5 points (range 0–5) and for the assessment of dietary intake, the mean score was 1·3 out of 2 points (range 1–2). Major weakness in study quality revolved around the failure to recruit representative samples and adjustment for confounding factors such as age, sex and level of education. Appropriate statistical methods and reporting of actual P values or variability estimates were also lacking in a number of the studies (Table 4).

Only eight of the twenty-nine studies used all five types of validation for the nutrition knowledge instruments, and seven studies failed to report any formal validation of the instrument used. The British-developed General Nutrition Knowledge Questionnaire( Reference Parmenter and Wardle 19 ) was the most extensively validated nutrition knowledge instrument. The General Nutrition Knowledge Questionnaire or an adaptation of this instrument was also the most commonly used (five of twenty-nine studies) nutrition knowledge tool. Approximately 60 % (seventeen studies) of the studies reported face and content validity in addition to pilot testing of the instrument used. Only 27·6 % (eight studies) conducted test–retest analysis and 4·1 % (twelve studies) an evaluation of internal consistency. Adaptation of original instruments was often conducted without validation of the changes incorporated.

Of the fourteen studies utilising the FFQ method of dietary assessment, eight used a validated FFQ, two used an FFQ with partial validation and four had no validation. Length of recording for dietary records varied between 2 and 3 d with only one study reporting appropriate outcomes for the length of recording conducted (e.g. energy and macronutrients, not micronutrients). Collection period for the 24 h recall varied between 1 and 3 d. Studies using a specific nutrient screener( Reference Block, Gillespie and Rosenbaum 24 ) or an (adapted) existing food pattern questionnaire( Reference Werblow, Fox and Henneman 61 , Reference Roe, Strong and Whiteside 63 ) all used validated instruments. Overall, only three studies( Reference Wardle, Parmenter and Waller 11 , Reference Harnack, Block and Subar 47 , Reference Sims 53 ) scored the full points for both nutrition knowledge and dietary intake measurement quality.

Significant positive associations in the community studies were more often observed in those conducted after the year 1990, using larger and representative samples, higher quality scores for statistics and adjustment of confounders, and validated nutrition knowledge and dietary intake measures, especially FFQ rather than dietary records to measure intake. Most of the studies (six out of nine scoring the full 2 points for dietary methodology quality) also showed a positive association with nutrition knowledge.

The athlete studies were generally older and lower in quality (9·4 v. 11·0) than those conducted in the community populations, with none using a representative sample and none using a well-validated nutrition knowledge instrument (scoring full 5 points) and appropriate measurement of dietary intake (scoring full 2 points).

Discussion

The present systematic review examined the relationship between nutrition knowledge and dietary intake in adults. Although it would seem both relevant and important to investigate the impact of nutrition knowledge on dietary intake, this question has received limited research attention. A total of twenty-nine relevant articles were identified, of which twenty-two were conducted in community populations and seven in athlete populations. Most of the studies (n 19/29; community: n 14/22; athletic: n 5/7) showed significant, positive, but weak (r< 0·5) associations between nutrition knowledge and some aspect of dietary intake, most often a higher intake of fruit and vegetables. Unfortunately, the studies informing the present systematic review are of varied quality, and relatively few( Reference Wardle, Parmenter and Waller 11 , Reference Kristal, Bowen and Curry 27 , Reference Byrd-Bredbenner, O'Connell and Shannon 42 , Reference De Vriendt, Matthys and Verbeke 43 , Reference Jovanovic, Kresic and Zezelj 48 , Reference Kresic, Jovanovic and Zezelj 49 , Reference Stafleu, Van Staveren and De Graaf 54 , Reference Hamilton, Thomson and Hopkins 57 ) used nutrition knowledge instruments that had been validated using the five key forms of validation used to assess quality in the present review. A limited number of studies measured or reported dietary intake appropriately( Reference Wardle, Parmenter and Waller 11 , Reference Dissen, Policastro and Quick 21 , Reference Baghurst and McMichael 40 , Reference Guthrie and Fulton 46 – Reference Jovanovic, Kresic and Zezelj 48 , Reference Sharma, Gernand and Day 51 , Reference Stafleu, Van Staveren and De Graaf 54 , Reference Rash, Malinauskas and Duffrin 60 ). Only three studies( Reference Wardle, Parmenter and Waller 11 , Reference Harnack, Block and Subar 47 , Reference Sims 53 ) used nutrition knowledge and dietary intake assessments that were both valid. As nutrition education is widespread in the community and represents a significant investment by schools, governments and health agencies, contemporary, high-quality research on the relationship between nutrition knowledge and dietary intake is required to evaluate and guide these initiatives into the future.

Although many factors including taste, convenience, food costs, cultural and religious beliefs are known to influence dietary intake( Reference Heaney, O'Connor and Michael 4 , Reference Hendrie, Coveney and Cox 9 – Reference Parmenter, Waller and Wardle 12 ), nutrition education programmes aim to improve knowledge and thereby positively influence dietary intake( Reference Lee, Lee and Kim 1 – Reference Heaney, O'Connor and Michael 4 ). The serious lack of well-designed, contemporary research in this area fails to explore the contribution of nutrition knowledge among these above-mentioned factors and a range of other factors that may influence dietary intake. Although it is implicit that one must have some basic knowledge of nutrition to guide food choice, nutrition education programmes, which focus purely on knowledge of facts or so-called declarative knowledge rather than process knowledge or practical skills, may be less effective in eliciting positive dietary change( Reference Worsley 5 ).

Much of the research fails to tease out the influence of specific aspects of nutrition knowledge on relevant dietary outcomes (e.g. knowledge of fat sources and fat intake). However, studies informing the present review that used nutrition knowledge instruments that had undergone more extensive validation or had a valid and appropriate dietary assessment more often uncovered significant, positive associations between nutrition knowledge and dietary intake. The lack of well-validated instruments to measure nutrition knowledge is a major limitation but also somewhat of a challenge to resolve, since instruments need to reflect contemporary nutrition knowledge and guidelines that are constantly evolving. They also need to be culturally sensitive, and this may be a challenge when assessing populations with diverse ethnicity.

Over the past 10 years, there has been increasing attention on the importance of ‘health literacy’, an umbrella term for which nutrition knowledge is an integral component( Reference Zoellner, Connell and Bounds 28 ). An adequate level of health literacy enables an individual to read, calculate and utilise verbal or written information related to health( Reference Nielsen-Bohlman, Panzer and Kindig 64 ). Therefore, an adequate degree of health literacy enables an individual to respond in their best interest. Components of health literacy include oral, print and media literacy, numeracy, and cultural and conceptual knowledge( Reference Zoellner, Connell and Bounds 28 , Reference Nielsen-Bohlman, Panzer and Kindig 64 , Reference Hindin, Contento and Gussow 65 ). Research shows that individuals with poor health literacy are less responsive to health education( Reference Schillinger, Barton and Karter 66 ), less successful in managing chronic disorders( Reference Caballero, Allen and Prentice 31 , Reference Nielsen-Bohlman, Panzer and Kindig 64 , Reference White, Chen and Atchison 67 – Reference Berkman, Sheridan and Donahue 69 ) and incur higher health costs( Reference Eichler, Wieser and Brügger 13 , Reference Vernon, Trujillo and Rosenbaum 14 ). A recent Australian study( Reference Adams, Appleton and Hill 18 ) has demonstrated that individuals with limited health literacy were significantly more likely to report having diabetes, cardiac disease or stroke and those ≥ 65 years were more likely to have been admitted to hospital. These negative health outcomes from low levels of health literacy have also been reported in other countries( Reference Baker, Gazmararian and Williams 70 – Reference Williams, Baker and Parker 72 ). Emerging evidence also shows that the level of health literacy may be lower than expected, with recent studies from Australia and the USA indicating that a substantial proportion (close to 50 % in some studies) of the population has limited health literacy( Reference Adams, Appleton and Hill 18 , Reference Zoellner, Connell and Bounds 28 , Reference Ibrahim, Reid and Shaw 71 ).

Although the level of health literacy and nutrition knowledge are probably associated, an adequate level of health literacy may not automatically translate to an adequate level of nutrition knowledge, specifically those aspects relevant to making appropriate dietary decisions( Reference Parker, Baker and Williams 73 ) or what Zoellner et al. ( Reference Zoellner, Connell and Bounds 28 ) define as ‘nutrition literacy’. Health literacy may be situation or topic specific. A recent study conducted in the USA has evaluated the impact of health literacy using a tool (Newest Vital Sign)( Reference Weiss, Mays and Martz 74 ) relevant to nutrition, as it included assessment of reading a food label. This study reported that for every 1 point increase in health literacy, there was a 1·21 point increase in the US Department of Agriculture Healthy Eating Index score. The association was significant (P< 0·01) even after controlling for all other relevant variables( Reference Zoellner, You and Connell 75 ). The health literacy score in this study also significantly predicted consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages (the lower the score, the higher the consumption). Although low health literacy has been linked with various poor health outcomes, this is one of the first studies to make a link with diet quality. Unfortunately, although research on health literacy has expanded in recent years, there are limited studies focusing specifically on how different aspects of nutrition knowledge and skills influence dietary intake and health.

Clearly, failure to evaluate the print and numeracy literacy of an instrument used to assess nutrition knowledge, or dietary intake (if written assessment is used), limits the capacity to assess outcomes, as this is confounded by an inability to read and comprehend the items. However, it is also clear that limited literacy is also probably a serious limitation for acquiring nutrition knowledge, selecting and implementing a healthy diet, and making other positive choices in relation to health( Reference Zoellner, Connell and Bounds 28 ). Although some of the studies informing the present review conducted pilot testing of the nutrition knowledge instrument used, none specifically evaluated the level of health literacy required for completion. The pilot testing was often performed on a small convenience sample, which was typically not adequately described and may not have emulated the demographic (and probably literacy) characteristics of the wider population of participants.

One aspect of nutrition knowledge that is either missing or under-represented from instruments used in the included studies is assessment of food label reading. Item descriptors did not include evaluation of food label reading, and this would seem to be a critical component of nutrition knowledge, particularly process knowledge required to make informed food selection. A number of studies have specifically examined food label reading skills, and evidence suggests that many consumers find this challenging( Reference Cowburn, Cowburn and Stockley 76 ). Understanding food labels requires sound literacy and numeracy skills in addition to knowledge of what ingredients or nutrients are desirable (e.g. whole grains, dietary fibre, etc.) or undesirable (e.g. saturated fat, salt, etc.). Some knowledge of the relative amounts of these ingredients or nutrients in the daily diet is also needed to implement a healthy eating plan( Reference Parmenter, Waller and Wardle 12 ). The lack of items probing food label reading skills within the instruments identified by the present review was surprising, but reflects the challenge of constructing an instrument to measure what could be considered as a diverse array of areas that can potentially be deemed related to nutrition knowledge.

A lack of consensus as to what should be included in instruments designed to measure nutrition knowledge is especially problematic for systematic review as pooling of studies for meta-analysis is not valid when outcome measurement is heterogeneous. Many of the instruments assessing nutrition knowledge were author-designed, only used for one study and had limited validation. The link between the items measuring nutrition knowledge and dietary intake was often not clarified or discussed. Items probing theoretical or declarative nutrition knowledge may have no relationship to the practical knowledge required to choose a healthy diet, i.e. knowing an orange is good source of vitamin C may not be related to knowing how many servings of the fruit are required to meet the dietary guidelines and satisfy nutrient reference values and then selection of a diet consistent with individual needs.

It would seem logical that future instruments include items that probe knowledge and understanding of dietary guidelines with assessment of practical knowledge including recommended servings of core foods and how to select foods with key health attributes (e.g. those lower in fat or salt) by reading a food label. Dietary assessment that probes adherence to dietary guidelines would then also seem the best approach to explore links between nutrition knowledge and dietary intake, as the knowledge being tested is logically related to the dietary outcomes. A lack of connectedness with nutrition knowledge and dietary intake assessments in a number of the articles possibly explains the weak or lack of association observed. The importance of probing both knowledge and understanding of dietary guidelines is supported by a recent systematic review exploring consumer responses to healthy eating, physical activity and weight-related guidelines. The review reported that many consumers found guidelines confusing, and that there was also a lack of research investigating the impact of guidelines on dietary behaviour( Reference Boylan, Louie and Gill 77 ).

Despite the weaknesses of the articles informing the present review, the majority reported a significant and positive association between nutrition knowledge and some aspect of dietary intake. Relatively few (n 5) studies reported negative associations, although approximately one-third failed to observe any association (n 10). Studies with larger samples and validated instruments used to measure nutrition knowledge or dietary intake more often observed significant positive associations. This is encouraging and supports investment in improving nutrition knowledge. Further research, which improves on flaws identified in the present review, would reduce measurement noise and be able to better characterise associations. Importantly, ongoing research should aim to identify which specific aspects of nutrition knowledge are more significantly associated with dietary intake. This would inform nutrition education from public health policy extending through to clinical counselling. Nutrition misconceptions and difficulty in understanding or comprehending dietary guidelines or food labels probably vary across populations, sexes and cultures, and a deeper understanding of this would help to provide education that is targeted and relevant. As a substantial amount of effort and public funding is directed at nutrition education initiatives, it is paramount that contemporary, high-quality research is undertaken. This would seem particularly important for populations with low socio-economic status who are most likely to have low health literacy and a greater risk of lifestyle disease, and for which the present review demonstrates that evidence is lacking. Evaluation of nutrition education campaigns is often restricted to basic awareness of the key messages with less comprehensive assessment of how such interventions change dietary behaviour( Reference Contento, Randell and Basch 78 , Reference Contento, Balch and Bronner 79 ). A better understanding of this relationship may assist in the development of more effective community nutrition education and guide-targeted public health policy and funding.

The limitations of the present review include the quality of the existing evidence. Quality rating scores ranged from 2 to 17 with a mean of 11·2. Some studies had weak designs, low sample size and power and few recruited representative samples. Of the twenty-nine studies, fourteen were conducted in either university students or athletes where the majority of the participants were tertiary educated. In fact, relatively few of the remaining fifteen studies included a diverse range of participants, including those with social disadvantage. A substantially higher number of females were recruited in the included studies, and there is a well known bias with both sex and socio-economic status for the level of nutrition knowledge( Reference Hendrie, Coveney and Cox 9 , Reference Wardle, Parmenter and Waller 11 , Reference Parmenter, Waller and Wardle 12 ). Clearly, studies in representative samples using well-validated instruments that also assess nutrition knowledge with practical relevance to appropriate food choice and adherence to dietary guidelines would seem relevant for the future. This may be less relevant to athletic populations who are known to have specific nutrition needs, although even in athletes, diets should still remain consistent with dietary guidelines.

In conclusion, the present review provides evidence of a weak, positive association between nutrition knowledge and dietary intake. However, the quality of the evidence is limited and future studies require the use of well-designed and well-validated instruments to assess nutrition knowledge and dietary intake. These instruments must identify the health literacy level necessary for completion and should be designed with the understanding that this may be low or limited in a wide sector of the population. It would seem implicit that items contributing to the nutrition knowledge assessment in the community populations be relevant to core facts and skills essential for selection of an appropriate diet. Logically, this should include at a minimum, knowledge and understanding of dietary guidelines, quantities of food groups needed to maintain health and the skill to discriminate between food products by reading a food label. Linking knowledge to dietary patterns or diet quality scores or indices that aim to assess the adherence to dietary guidelines would then seem most effective for assessing the relationship between nutrition knowledge and dietary intake. As the burden of nutrition-related disease continues to rise worldwide, it would seem paramount to invest in high-quality research to advance and refine the measurement of nutrition knowledge for the future. Contemporary research will guide evidence-based nutrition education initiatives and public health policy and optimise public health campaign effectiveness to reduce the burden of diet-related disease.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge Dr Janelle Gifford (Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Sydney) for editorial assistance.

The present review did not receive any funding or sponsorship.

The authors' contributions are as follows: I. S., C. B. and H. O. contributed to the conception and design of the review. All authors contributed to the interpretation and analysis of the data and to the writing and editing of the manuscript.

None of the authors has any conflict of interest to declare.