Michael Poyurovsky conducts research on antipsychotic-induced extrapyramidal side-effects, particularly acute akathisia, and heads the department of first-episode psychosis in an in-patient university-affiliated hospital. He is Associate Professor and Chairman of Psychiatry at the Rappaport Faculty of Medicine in the Technion, Israel Institute of Technology, Haifa, Israel.

Akathisia was initially observed in patients with basal ganglia disorders, primarily Parkinson's disease. Introduction of first-generation antipsychotic (FGA) agents drew attention to anti-psychotic-induced akathisia as it appeared to be one of the most frequent and distressing drug-induced movement disorders, occurring in around one in four FGA-treated patients. It is characterised by restless movements and a subjective sense of inner restlessness coupled with distress, and develops predominantly in patients treated with high-potency FGAs, at high doses and during rapid dose escalation. The identification of akathisia in a meaningful proportion of patients treated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and its association with suicidal behaviour highlights its clinical significance. Akathisia also afflicts a substantial proportion of patients treated with preoperative sedatives, calcium channel blockers, and anti-emetic and anti-vertigo agents, posing a diagnostic and treatment challenge in non-psychiatric populations as well. Early detection and rapid amelioration of acute akathisia are essential since it is a risk factor for psychotic exacerbation and non-adherence to pharmacotherapy. Intercorrelation between akathisia, depressive symptoms and impulsiveness may account for suicidal and violent behaviour in patients with akathisia.

Akathisia and second-generation antipsychotics

Although low propensity to induce extrapyramidal side-effects (EPS) such as acute dystonia, Parkinsonism and tardive dyskinesia is a defining feature of second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs), this seems not to hold true for akathisia. Reference Kane, Fleischhacker, Hansen, Perlis, Pikalov and Assunção-Talbott1 The Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) revealed no significant differences between the intermediate-potency FGA perphenazine and four SGAs (olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, ziprasidone) in the percentage of patients with chronic schizophrenia who developed acute akathisia. Reference Lieberman, Stroup, McEvoy, Swartz, Rosenheck and Perkins2 Subsequent rigorous analysis of the CATIE results using multiple criteria of akathisia (Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale (BARS) score ≥2, administration of anti-akathisia medications, treatment discontinuation owing to akathisia) estimated the covariate-adjusted 12-month akathisia rate at 26–35% for SGAs and 35% for perphenazine, with a trend towards more perphenazine- and risperidone-treated patients having anti-akathisia medications added. Reference Miller, Caroff, Davis, Rosenheck, McEvoy and Saltz3

A substantial rate of acute akathisia induced by the SGAs amisulpride (200–800 mg, 16%), olanzapine (5–20 mg, 10%), quetiapine (200–750 mg, 13%) and ziprasidone (40–160 mg, 28%) was shown in the European First Episode Schizophrenia Trial. Reference Kahn, Fleischhacker, Boter, Davidson, Vergouwe and Keet4 Lack of a substantial difference in moderate-to-severe akathisia (BARS score ≥3) between the FGA molindone (10–140 mg) and the SGAs olanzapine (2.5–20 mg) and risperidone (0.5–6 mg) was substantiated in adolescents in the Treatment of Early-Onset Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders study (18%, 13% and 8% respectively). Reference Sikich, Frazier, McClellan, Findling, Vitiello and Ritz5 A remarkably high rate of akathisia (about 15–25%) was reported in patients treated with the partial dopamine agonist aripiprazole, leading the manufacturer to refer to akathisia as one of aripiprazole's most frequent and troublesome side-effects.

It seems that SGAs are not alike in their propensity to provoke akathisia. Risperidone, ziprasidone and aripiprazole possess a higher risk than olanzapine, whereas quetiapine and clozapine present the lowest risk, although explicit comparative evaluation is lacking. Reference Kane, Fleischhacker, Hansen, Perlis, Pikalov and Assunção-Talbott1 Notably, SGA-treated patients with affective disorders, primarily bipolar depression, are even more vulnerable to develop akathisia than patients with schizophrenia. Reference Gao, Kemp, Ganocy, Gajwani, Xia and Calabrese6

Current treatment options for akathisia

Beta-adrenergic blockers

Propranolol, a non-selective lipophilic beta-adrenergic antagonist, was used as a first-line anti-akathisia agent for decades. Surprisingly, this treatment was not supported by large-scale controlled trials. The robust anti-akathisia effect of propranolol was substantiated in the largest-to-date akathisia trial (see Poyurovsky et al). Reference Poyurovsky, Pashinian, Weizman, Fuchs and Weizman7 Propranolol tolerability, however, was poor and a substantial proportion (20%, 6 of 30 patients) developed clinically meaningful orthostatic hypotension and bradycardia prompting premature drug discontinuation. Additional drawbacks of propranolol co-administration with antipsychotics are increased complexity in administration and titration schedules as well as contraindications for propranolol use (diabetes mellitus, cardiac conductance impairment, bronchial asthma).

Anticholinergic agents

Although anticholinergics have proven efficacy in antipsychotic-induced Parkinsonism and dystonia, their clinical utility in akathisia remains unclear. A recent short-term placebo-controlled trial revealed no difference between intramuscular biperiden and placebo in patients with FGA-induced akathisia. Reference Baskak, Atbasoglu, Ozguven, Saka and Gogus8 Anticholinergic-induced side-effects further limit their use in antipsychotic-treated patients. Barnes & McPhillips' suggestion to use anticholinergics only in patients with akathisia who have associated Parkinsonian symptoms seems to hold true, although explicit evaluation is warranted. Reference Barnes and McPhillips9

Benzodiazepines

Benzodiazepines have some therapeutic value in antipsychotic-induced akathisia, putatively owing to their non-specific anti-anxiety and sedative effects. Nevertheless, clinical experience shows that these effects are not sufficient to ameliorate akathisia.

Newer treatment options

In a previous editorial in this Journal we suggested agents with marked 5-HT2A receptor antagonism (mianserin, cyproheptadine) as anti-akathisia remedies based on their potential to counteract antipsychotic-induced dopamine D2 receptor blockade by increasing dopamine neurotransmission. Reference Poyurovsky and Weizman10 Indeed, small randomised placebo-controlled trials consistently demonstrated anti-akathisia properties, safety and tolerability of mianserin and cyproheptadine in FGA-treated patients with akathisia. Reference Poyurovsky and Weizman10 Mild sedation and non-clinically significant orthostatic hypotension were the only side-effects. Both compounds did not interfere with the antipsychotic effects of FGAs.

Low-dose mirtazapine

The most compelling evidence indicating that 5-HT2A antagonists may represent a new class of effective anti-akathisia agent comes from the largest-to-date randomised controlled trial comparing low-dose mirtazapine with propranolol in 90 patients with FGA-induced acute akathisia. Reference Poyurovsky, Pashinian, Weizman, Fuchs and Weizman7 Mirtazapine is characterised by potent presynaptic alpha-2 adrenergic antagonism, which accounts for its antidepressant activity, and marked 5-HT2A blockade that seems to preponderate in a low dose and contribute to its anti-akathisia properties. Mirtazapine, given once daily (15 mg) was as effective as propranolol (80 mg twice daily) in producing a greater improvement in akathisia compared with placebo (reduction in BARS global scale: 1.10 (s.d. = 1.37) points (34%) and 0.80 (s.d. = 1.11) points (29%) v. 0.37 (s.d. = 0.72) points (11%) respectively; P = 0.036). Responder analysis (BARS global scale reduction ≥2) yielded a similar robust anti-akathisia effect in mirtazapine and propranolol v. placebo (43.3% and 30% v. 6.7% respectively; P = 0.005). Low numbers needed to treat (3 and 4 respectively) support high clinical efficacy of both compounds. Importantly, mirtazapine achieved an anti-akathisia effect with more convenient dosing than propranolol and better tolerability, with mild transient sedation as the only observed side-effect. The favourable mirtazapine safety profile was also supported by the absence of significant changes in vital signs. Mirtazapine did not interfere with the antipsychotic effect of FGAs.

Long-term use of mirtazapine, however, can be associated with weight gain, and very rarely with agranulocytosis. Notably, mirtazapine and propranolol had no effect on Parkinsonian symptoms coincident with akathisia, reinforcing the hypothesis that antipsychotic-induced Parkinsonism might be related to dopamine/acetylcholine dysfunction and may preferentially respond to anticholinergic agents. An imbalance between dopaminergic and noradrenergic/serotonergic systems seems to predominate in acute akathisia that responds to beta-adrenergic and 5-HT2A antagonists.

Suggested treatment guidelines for acute akathisia

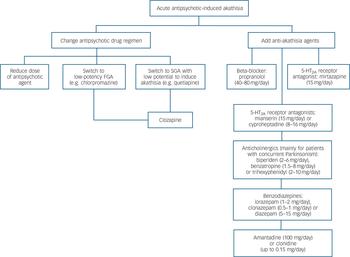

Systematic evaluation of agents with marked 5-HT2A receptor antagonism in acute akathisia prompts modification of the previously suggested guidelines. Reference Poyurovsky and Weizman10 There are two major treatment strategies: modification of the antipsychotic drug regimen and/or the addition of an anti-akathisia agent. The former includes a dose reduction of the culprit antipsychotic, switch to a low-potency FGA (e.g. chlorpromazine) or to a more commonly used SGA with low potential to induce akathisia (e.g. quetiapine), and if necessary initiation of clozapine in cases of intractable akathisia. Noteworthy, the CATIE investigators showed that patients with perphenazine-induced akathisia are particularly vulnerable to this side-effect when medication is switched to risperidone. It is plausible that this holds true when switching to other SGAs with high akathisia potential (e.g. ziprasidone, aripiprazole), although evidence is lacking.

When the decision is to add an anti-akathisia agent, propranolol (40–80 mg/day twice daily) or low-dose mirtazapine (15 mg once daily) as first-line treatment have the most supportive evidence. Mianserin (15 mg once daily) and cyproheptadine (8–16 mg/day) are alternative options; however, large-scale trials are not yet available.

In antipsychotic-induced akathisia associated with Parkinsonism, anticholinergic agents (e.g. biperiden, trihexyphenidyl, benzatropine) may be considered. Non-specific anxiolytic and sedative effects of benzodiazepines alone or in combination with propranolol may be beneficial in some patients. Co-administration of benzodiazepines with mirtazapine, mianserin and cyproheptadine should be avoided owing to their shared sedative properties. Clonidine and amantadine may be tried if other options have failed (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Proposed treatment guidelines for acute antipsychotic-induced akathisia.

FGA, first-generation antipsychotic; SGA, second-generation antipsychotic. An earlier version of these guidelines has been published.

Future directions

Elucidation of an anti-akathisia effect of mirtazapine and other agents with marked 5-HT2A antagonism in patients with SGA-induced akathisia is a reasonable next stage. Among SGAs, aripiprazole is distinguished by a low affinity for the 5-HT2A receptor, hence additional 5-HT2A antagonism may be required to mitigate aripiprazole-induced akathisia. Reference Poyurovsky, Weizman and Weizman11 Since mirtazapine exhibits an antagonistic effect on multiple receptors, evaluation of the anti-akathisia properties of selective 5-HT2A antagonists might further clarify the role of this mechanism in the pathophysiology of akathisia. Notably, the selective inverse agonist pimavansarin ameliorates haloperidol-induced akathisia in healthy volunteers. Reference Abbas and Roth12

Additional receptor mechanisms within the serotonergic system may underlie an anti-akathisia effect. Indeed, a selective 5-HT1D receptor agonist zolmitriptan (7.5 mg/day) revealed anti-akathisia properties comparable to those of propranolol, although its clinical utility is not yet clarified. Reference Avital, Gross-Isseroff, Stryjer, Hermesh, Weizman and Shiloh13 Along an intriguing new line of thought beyond adrenergic/serotonergic mechanisms, adenosine-2A receptor antagonists may represent potentially active anti-akathisia agents owing to their ability to increase dopaminergic neurotransmission in the striatum, as evidenced by their efficacy in animal models of EPS. Reference Varty, Hodgson, Pond, Grzelak, Parker and Hunter14

As noted, akathisia may be ‘forgotten, but it is indeed not gone’. Effective, safe and easy-to-use anti-akathisia agents remain a major unmet need in antipsychotic-induced akathisia that merits a search for new remedies.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.