1. Introduction: Towards a professional movement

As a result of the inception of critically oriented research paradigms (e.g., World Englishes, English as an International Language, and English as a Lingua Franca, Global Englishes) from the mid-1970s onwards, scholars began to critically scrutinize the global/glocal spread of English and the diverse roles, forms, uses, users, functions, and statuses of English(es) in sociocultural and sociopolitical contexts around the world (Selvi, Reference Selvi and de Oliveira2019a). The proliferation of research endeavors within these paradigms and the burgeoning interest in the notion of (teacher) identity collectively served as a fertile line of inquiry for the scholars in English language teaching (ELT) and applied linguistics in the 1980s (e.g., Medgyes, Reference Medgyes1983; Paikeday, Reference Paikeday1985), the 1990s (e.g., Braine, Reference Braine1999; Medgyes, Reference Medgyes1992, Reference Medgyes1994; Phillipson, Reference Phillipson1992; Widdowson, Reference Widdowson1994), and the 2000s (e.g., Braine, Reference Braine2010; Doerr, Reference Doerr2009; Kamhi-Stein, Reference Kamhi-Stein2004; Llurda, Reference Llurda2005; Mahboob, Reference Mahboob2010). It primarily centered on deconstructing the idealization and essentialization with the categories of linguistic (i.e., “native” speaker [NSFootnote 1] and “non-native” speaker [NNS1]) and professional identity (i.e., “native” English-speaking teachers [NESTsFootnote 1] and “non-native” English-speaking teachers [NNESTs1]) and problematizing discrimination/discriminatory practices (particularly in hiring practices and workplace settings), which ultimately transformed itself into a professional movement, known as the “NNEST movement” (Braine, Reference Braine2010; Kamhi-Stein, Reference Kamhi-Stein2016).

The NNEST movement is situated at the nexus of ELT and applied linguistics and operationalized at the level of theoretical, practical, and professional levels in ELT (Selvi, Reference Selvi2014). It promotes the legitimacy of ethnic, racial, cultural, religious, gender, and linguistic diversity in ELT and utilizes this position as a defining benchmark in ELT, both as a profession (e.g., issues of professionalism, standards, teacher education, hiring, and workplace) and as an instructional practice (e.g., the benchmark for learning, teaching, assessment, methodology, and material development). As shown in Figure 1, the “NNEST movement” rests upon three fundamental pillars, namely:

(1) research efforts, manuscripts, research articles, opinion pieces, presentations, workshops, seminars, and colloquia in conferences, and theses and dissertations;

(2) policy and advocacy initiatives, the establishment of advocacy-oriented entities within professional associations, white papers, and position statements, and advocacy groups organized on online platforms and social-networking sites;

(3) teaching activities, infusion of critical issues of language ownership, learning, use, instruction into in-/pre-service second language teacher education curricula and activities by means of readings, discussions, tasks, and assignments.

Figure 1. Three pillars of the NNEST movement (adapted from Selvi, Reference Selvi2014, Reference Selvi, Mann and Walsh2019b)

In this picture, research efforts have been the prime force that pushed scholarly thinking, challenged widely held beliefs, and served as a catalyst for policy/advocacy initiatives and teaching activities. Since the 1980s, the number of publications focusing on the roles and issues related to ELT professionals (both NESTs and NNESTs) has been growing steadily and is expected to continue doing so in the future. The proliferation in terms of the types of publication, representations of diverse geographical contexts around the world, the recent increase in literature reviews offering big-picture syntheses, and the publication of a section (with 45 entries) in the recent TESOL Encyclopedia of English Language Teaching are collective testaments to this fertile domain of scholarly inquiry at the nexus of ELT and applied linguistics (see Table 1). Therefore, in a state-of-the-art review focusing on the current situation, it is imperative to recognize and appreciate the momentous efforts of scholars around the world who made substantial contributions to our understanding.

Table 1. An overview of the scholarship: Major outletsFootnote 4

Conceptual and ideological diversity and divergences have marked the research base of the critically oriented scholarship (and pertinent discourses, discussions, and conversations) focusing on ELT professionals. As will be discussed more extensively in the next section, in recent years, a new line of poststructuralist scholarship has begun to emerge in response to the growing dissatisfaction with the mutually exclusive demarcations and binary juxtapositions among ELT professionals leading to the essentialization and fixation of identities and experiences related to (in)equity, privilege, and marginalization in ELT. Departing from this premise, the “NNEST movement” has received growing criticism for building upon the most prevalent and problematic construct (i.e., NNEST), falling into the trap of promoting a unidimensional approach to criticality and “fail[ing] to directly address both the neoliberal spread of English and the supremacy of English in discussions of bi-/trans-/multi-/plurilingualism” (Rudolph, Reference Rudolph2018a, november 22). nathanael rudolph. nnest of the month blog. https://nnestofthemonth.wordpress.com/2018/11/22/nathanael-rudolph/).

Studies suggest that teacher educators in diverse teaching settings around the world strive to integrate critical issues related to (the English) language (e.g., ownership, standards, legitimacy, identity, use, variation, instruction, and development) into teacher education activities by means of readings, discussions, tasks, assignments, and experiences fostering and documenting professional identity constructions both at pre-service (e.g., Aneja, Reference Aneja2016a; Schreiber, Reference Schreiber2019; Wolff & De Costa, Reference Wolff and De Costa2017; Yazan, Reference Yazan2019b) and in-service teacher education (e.g., Trent, Reference Trent2016). Even though more systematic and comprehensive documentation of teaching and teacher education efforts is necessary for this line of inquiry, teacher education continues to serve as an intellectual bridge between a growing locus of scholarship and the ongoing efforts to support teachers’ identity development in (in)formal teacher education and continuous professional development settings (Selvi, Reference Selvi, Mann and Walsh2019b). Teacher education practices are powerful manifestations, experiences, and sites that have the potential for teachers to resist, interrogate, and transform monolingual/monocultural orientations to language, and monolithic, juxtaposed, and binary-oriented orientations to language teacher identities.

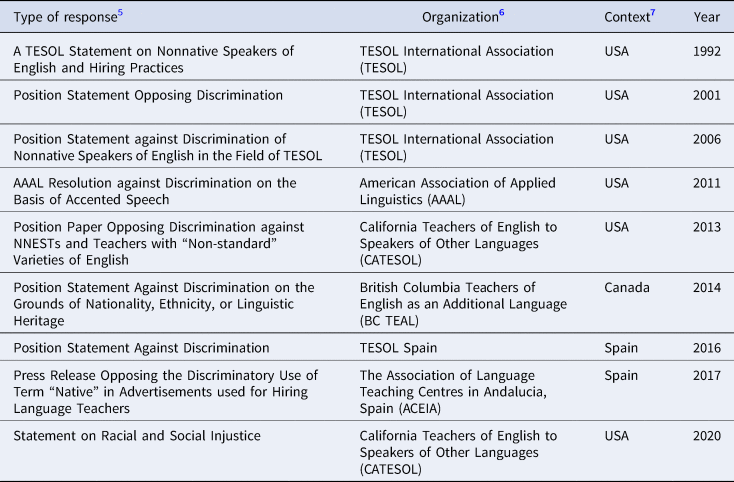

The research efforts and teaching activities focusing on unethical and unprofessional practices against ELT professionals have always served as a powerful catalyst for policy and advocacy initiatives. These initiatives stood out as a complementary strand with a motivation to develop systemic and institutionalized responses to unethical and unprofessional practices in ELT and promote the professional stature of the ELT profession by establishing an egalitarian professional landscape conducive to professionals’ negotiations of ethnic, racial, cultural, religious, gender, and linguistic identities. The past decade witnessed three major trends in policy and advocacy initiatives related to ELT professionals. First, professional associations involved in languages, language teaching, and teachers and entities therein continued raising their voices against inequity and discrimination by issuing numerous position statements and papers (AAAL, 2011; ACEIA, 2017; BC TEAL, 2014; CATESOL, 2013, 2020; TESOL, 1992, 2001, 2006; TESOL Spain, 2016) (see Table 2).

Table 2. Institutionalized responses against discrimination in ELT (in chronological order)

Second, the exponential growth in information technologies and social-networking sites charted new territories and transformed advocacy-oriented professional groups (e.g., NNEST Facebook Group, TEFL Equity Advocates website, Multilinguals in TESOL Blog, Twitter hashtags, and accounts focusing on discrimination, among others) into the digital world. Third, recent scholarship has advocated that (in)equity, privilege, and marginalization in ELT are not uniformly experienced within (i.e., by both NESTs and NNESTs in a context-dependent manner) and across (i.e., not only by NNESTs, therefore invalidating universalized generalizations) closed categories of identity (Rudolph, Reference Rudolph2019; Rudolph et al., Reference Rudolph, Selvi and Yazan2015; Wicaksono, Reference Wicaksono, Hall and Wicaksono2020). Moreover, together with personal and professional traits (e.g., race, ethnicity, country of origin, gender, religion, sexual orientation, schooling, passport/visa status, and physical appearance, among others), (perceived/ascribed) “nativeness” should be conceptualized in an intersectional manner as “part of a larger complex of interconnected prejudices” (Houghton & Rivers, Reference Houghton and Rivers2013, p. 14). Despite this conceptual elaboration and complexification in approaches to (in)equity, privilege, and marginalization in ELT, inequalities and discriminatory practices continue to remain realities of the ELT profession faced by millions of ELT practitioners (regardless of their labels) both in hiring processes and workplace settings (e.g., Charles, Reference Charles2019; Rivers, Reference Rivers, Copland, Garton and Mann2016; Ruecker & Ives, Reference Ruecker and Ives2015).

2. Beyond a professional movement: Conceptual divergences and multiple discourses

Since voicing their concerns over the idealized “native speaker” construct that (in)forms goals, norms, benchmarks, and instructional qualities of ELT practitioners, scholars around the world have contributed to a comprehensive research agenda offering critiques of this construct and its damaging implications in ELT (Moussu & Llurda, Reference Moussu and Llurda2008). In a nutshell, the early research in this domain brought about significant outcomes (and pertinent scholarship, discourses, and conversations), establishing a research base for the empowerment of NNESTs, inspiring advocacy efforts and responses against inequity, marginalization, and discrimination in ELT, and invalidating the perennial “who's worth more, the native or the nonnative?” question (Medgyes, Reference Medgyes1992). This conceptual position, dominating the research agenda through most of the 1990s and 2000s, has continued to expand in the past decade with contributions from all around the world. Today, many ELT professionals may inadvertently adhere to the superiority of “NS” as a language user (and thereby “NEST” as a language teacher) as a result of “compulsory native speakerism” (Selvi, Reference Selvi, Mann and Walsh2019b, p. 186), which refers to “the set of institutionalized practices, values and beliefs that normalize and impose the construction, maintenance and perpetuation of discourses that juxtapose language user (“NS”/“NNS”), and concomitantly, language teacher (“NEST”/”NNEST”) status in various facets of the ELT enterprise” (p. 186).

Some studies relied on binary juxtapositions of mutually exclusive categories of identity (e.g., “NS” vs. “NNS,” “NEST” vs. “NNEST,” “us” vs. “them,” “local” vs. “expatriates,” “Western” vs. “non-Western,” “knowledgeable” vs. “non-knowledgeable,” “in” vs. “out,” and “Center” vs. “Periphery,” “monolingual” vs. “multilingual,” “privileged” vs. “marginalized,” etc.) in exploring teachers’ competence, professional identity, and (in)equity, privilege, marginalization, and discrimination. This position, captured by Medgyes's (Reference Medgyes1994) “two different species” argument, (in)advertently perpetuates an antagonistic relationship (i.e., us vs. them) among ELT professionals and continues to reify problematic demarcations among teachers based on value-laden, identity-shaping, and confidence-affecting a priori definitions and distributions of essentialized and idealizedFootnote 2 linguistic, cultural, and instructional authority and superiority.

In the past decade or so, scholars adopted a novel and promising line of scholarship aiming to reposition the decontextualized, unidirectional, essentialized, historicized, and universalized orientations to theorizing language and language teacher identity (LTI) (Menard-Warwick, Reference Menard-Warwick2008; Rudolph et al., Reference Rudolph, Selvi and Yazan2015). Informed by poststructuralist perspectives, scholars scrutinize the discursive and performative (co-)construction and (re)negotiation of subjectivities in a dynamic and fluid manner across time and space (Aneja, Reference Aneja2016a; Bonfiglio, Reference Bonfiglio2013; Lee & Canagarajah, Reference Lee and Canagarajah2019). Consequently, these studies lead to a broader and deeper understanding of sociohistorically situated and contextualized negotiations of trans-lingual/-cultural/-national identities as opposed to oversimplified and essentialized binary oppositions (i.e., “NS” and “NNS”) and their extensions (i.e., NEST and NNEST). For scholars positioning themselves and their work with this line of scholarship, this conceptual stance affords liberation from the essentialized truths propagated by these problematic terms and the reification of a priori formulations of who individuals “were,” “are,” “will,” “could,” and/or “should” be and become as learners, users, and professionals of English in and beyond contextualized ELT (Rudolph, Reference Rudolph2019). In a nutshell, the recent research in this domain brought about significant outcomes – creating a novel intellectual space for individuals whose voices and experiences are silenced by categorical approaches to identity, experience, knowledge, and skills, underscoring the fluidity, complexity, and contextuality in experiencing inequity, privilege, marginalization, and discrimination in ELT, and revisiting and destabilizing widely held assumptions normalized within critically oriented scholarship in ELT (Rudolph et al., Reference Rudolph, Yazan and Rudolph2019).

A review of the trajectory of scholarship (and related advocacy practices) in this domain reveals the coexistence of discourses of equity with multiple and (at times) contradictory conceptualizations. While the research (and associated advocacy practices) using NEST and NNEST labels made substantial contributions to raising the voice of marginalized educators whose instructional competencies and identities are reduced to the “non-” prefix and defined in terms of NESTs (Selvi, Reference Selvi2014), it (inadvertently) subscribes to normative, essentialized, and categorical assumptions about professionals, strips away contextualized accounts of identity, experience, and (in)equity, and reduces privilege-marginalization in ELT exclusively on (non)nativeness. Even though the poststructuralist orientation to teacher identity rejected the use of contested labels and prioritized contextual apprehension of discourses (e.g., inequity, privilege, marginalization, and discrimination) over categorical juxtapositions (Yazan & Rudolph, Reference Yazan and Rudolph2018), much of these efforts are currently stuck at the level of abstraction and transform relatively (more into teacher education owing to the dual role of researchers as teacher educators and) less into advocacy initiatives, hiring practices, and workplace settings. Even though critically oriented scholars have been pushing the field forward by “(en)countering” (Swan et al., Reference Swan, Aboshiha and Holliday2015), “tackling” (Lowe & Kiczkowiak, Reference Lowe, Kiczkowiak and Bayyurt2021), “negotiating” (Galloway, Reference Galloway and Bayyurt2021), “redefining” (Houghton & Rivers, Reference Houghton and Rivers2013), “reconceptualizing” (Matsuda, Reference Matsuda and Bayyurt2021), “moving beyond” (Houghton et al., Reference Houghton, Rivers and Hashimoto2018; Selvi & Yazan, Reference Selvi, Yazan and Bayyurt2021a), and “undoing” (Houghton & Bouchard, Reference Houghton and Bouchard2020) “native speakerism,” this worldview and its manifestations in the form of structural inequalities and discriminatory practices continue to pose barriers to the professional fabric of ELT. Considering that both research traditions have a common denominator towards the establishment of a more egalitarian professional landscape characterized by equity, professionalism, and legitimate participation for all, future research efforts and pertinent advocacy initiatives need to seek a climate and convocation of dialogue in establishing concerted efforts towards a better and more professional future in/for the ELT profession(al).

3. Method: Research questions, criteria, rationale, and procedures

Scholars in various fields have retrospective (mapping developmental trajectories), perspective (identifying current strengths, weaknesses, and gaps in knowledge), and prospective (making suggestions for future research directions) motivations to review a body of literature on a scholarly topic. Such reviews have gained considerable popularity among scholars in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL) and applied linguistics and resulted in various types, including but not limited to review articles (e.g., Moussu & Llurda, Reference Moussu and Llurda2008; Von Esch et al., Reference Von Esch, Motha and Kubota2020), systematic reviews (e.g., Rose et al., Reference Rose, McKinley and Galloway2021), meta-analyses (e.g., Faez et al., Reference Faez, Karas and Uchihara2021), and scoping reviews (e.g., Hillman et al., Reference Hillman, Selvi and Yazan2021). We purposefully situate our work as a literature review since it aims to depict the big picture in this line of scholarship with a clear portrayal of the breadth and depth of our specific focus.

This critical literature review aims to describe, evaluate, and guide the existing scholarship focusing on a range of complex issues related to ELT professionals traditionally conceptualized as “native” and “non-native” English-speaking teachers spanning over several decades. More specifically, it was informed by these two broad research questions:

1. What are the major characteristics of the scholarship related to ELT professionals traditionally conceptualized as “native” and “non-native” English-speaking teachers in the past 15 years?

2. How does the scholarship contribute to our understanding of (in)equity, discrimination, privilege, and marginalization related to ELT professionals?

To ensure scientific rigor, methodological robustness, and analytical systematicity, we embarked upon our critical literature review by developing an a priori inclusion/exclusion criteria to be used in the assessment of scholarship focusing on a range of issues related to ELT professionals traditionally conceptualized as “native” and “non-native” English-speaking teachers. Utilized by the members of our research team who are involved in this line of scholarship, these criteria were used not just in defining and refining the methodological parameters for the present study, but also served as an internal accuracy checking mechanism employed iteratively. Previous reviews (e.g., Moussu & Llurda, Reference Moussu and Llurda2008; Selvi, Reference Selvi2014) and perfunctory analyses of themes and topics evident in major international events (e.g., Annual TESOL Convention and Expo, American Association of Applied Linguistics Conference) served as points of reference in our initial brainstorming process.

More specifically, our inclusion/exclusion criteria were as follows:

1. Time frame: Must have been published after 2008

We focused on the developmental trajectory of this line of scholarship after the appearance of the first critical literature review (i.e., Moussu & Llurda, Reference Moussu and Llurda2008) in Language Teaching. This seminal work served as the point of departure undergirding our work.

2. Professional focus: Must be related to ELT professionals

To achieve a more refined and focused understanding of the scholarship, we purposefully focused on ELT professionals. That said, we recognize that the issues of (in)equity, discrimination, privilege, and marginalization pertinent to “nativeness” (or lack thereof) transcend traditional linguistic borders and boundaries and, therefore, apply to millions of educators teaching languages other than English.

3. Topics/themes: Must be about identity, (in)equity, discrimination, privilege, or marginalization of ELT professionals

To maintain a conceptual congruence, we closely examined studies and investigations with a clear focus on ELT professionals’ identity negotiations and experiences of (in)equity, discrimination, privilege, and marginalization. This involved (self)attitudes, language proficiency, teacher identity, teaching efficacy/competency, advocacy (e.g., [in]equity, discrimination, privilege, and marginalization), and terminology (NESTs/NNESTs and other terms), among others.

To promote the comprehensiveness of our literature review, except for the type of scholarship to include only peer-reviewed journal articles and book chapters, no exclusion criteria were applied with regard to:

(a) empiricity (e.g., review, conceptual, and empirical studies);

(b) conceptual/ideological orientations (e.g., poststructuralism/postmodernism, critical race theory, critical pedagogy, translingualism/translanguaging, etc.);

(c) methodological tools (e.g., questionnaires, (semi-structured) interviews, auto-/duo-/trio-ethnography and narrative inquiry, etc.);

(d) professional foci (e.g., ELT professionals working at various levels and settings);

(e) contextual foci (e.g., professionals working in diverse contexts around the world), and

(f) target stakeholders (e.g., teachers, students, administrators, etc.).

Having identified initial guiding research questions and reached a consensus on the working criteria to assess the relevancy of the scholarship in the literature, we embarked upon an iterative process of searching for a scholarship, developing new search strategies, and deciding for the inclusion/exclusion in the final sample.

Next, we systematically searched the most widely used scholarly databases (e.g., Educational Resources Information Center [ERIC], Journal Storage [JSTOR], Linguistics and Language Behavior Abstracts [LLBA], Scopus, and Web of Science), social networking sites for researchers (e.g., Academia.edu, Google Scholar, and ResearchGate), and search engines (e.g., Google). Our searches used such expressions and professional acronyms such as “native English-speaking language teachers,” or “nonnative English-speaking language teachers,” or “NESTs,” or “NNESTs,” keywords such as “native” and “English” and “teachers,” and “non-native” and “English” and “teachers,” and keywords such as “inequity,” or “inequality,” or “privilege,” or “marginalization,” and or “discrimination.” The scholarship gleaned from multiple databases and platforms was recorded in a Google Excel spreadsheet to facilitate collaborative work since our research team is located on three different continents. The examination of titles, abstracts, keywords, and even contents both individually and as a group yielded discussions around: (a) confirming and removing duplicates, (b) reaching an inclusion/exclusion decision, and (c) generating a matrix for data analysis.

After collecting the studies that meet the above-mentioned criteria, we collated them into two folders as empirical and conceptual studies. As we read each study, we completed the initial synthesis by entering the following information into two matrices shared on Google Sheets:

1. Conceptual articles: Citation, purpose, theoretical/conceptual framework, methods, scope, findings, and contributions to current scholarly conversations on NNESTs/NESTs;

2. Empirical articles: Citation, research questions, research focus/purpose, theoretical/conceptual framework, methodological orientation, data collected, participants, findings, and contributions to current scholarly conversations on NNESTs/NESTs.

We had entered 170 empirical studies and 18 conceptual articles by the time we completed the initial synthesis of the studies collated. Looking over our notes, we decided to remove 46 of the empirical studies since they were only very remotely relevant to the NNESTs/NESTs. In the second round of review, Ali Fuad and Bedrettin considered Moussu and Llurda's (Reference Moussu and Llurda2008) findings and worked separately to assign initial codes to the articles such as “teacher identity,” “nomenclature debate,” “advocacy,” “innovative methods,” and “stakeholders.” Then, they met to go over the codes to make sure they were on the same page and needed to adjust some of the codes by discussing the convergences and divergences in their coding process. When they reached an agreement, they shared those codes with Ahmar to cross-check. In the third stage of the review, Ali Fuad and Bedrettin collated the articles based on the codes, and some articles were classified into multiple groups. For example, they grouped all articles (empirical and conceptual) which explore or review the issues of teacher identity in relation to NNESTs/NESTs. They individually carried out more detailed coding to make critical observations of the recent developments (e.g., the dimensions of gender, race, ethnicity, sexuality, emotions vis-à-vis linguistic identity of NNS/NS) in NNEST/NEST research which uses LTI as a conceptual lens. When they completed that stage, they met to discuss their codes and potential disagreements, which were later validated by Ahmar. Once we were all in agreement, we outlined the three main sections of the article, namely: (1) established domains of inquiry, (2) new domains of inquiry, and (3) inspiring extensions.

4. Established domains of inquiry

In the past decade, scholarly inquiry on ELT professionals maintained its progress by expanding its existing research base that focuses on the set of established foci (e.g., relative and comparative advantages and challenges of NESTs and NNESTs, preferences towards NESTs and NNESTs, beliefs held by multiple stakeholders, and documentation of discriminatory practices), participants (e.g., individuals in ELT teacher education programs), settings (e.g., teacher education programs, intensive English programs, K-12 and post-secondary institutions), and contexts (e.g., Global North and East Asia).

4.1 The LTI and the NNEST intersection

There are substantive overlaps between the emergence and growth of the research on LTI and the research on NNESTs. That macroscopic observation presumes NNEST and LTI as two sub-strands of research that are situated within the applied linguistics/TESOL scholarship. From the very beginning of the scholarly conversations on NNESTs (see Amin, Reference Amin1997; Braine, Reference Braine1999; Medgyes, Reference Medgyes1992), the idea of identity was at the forefront, and, similarly, the earliest LTI studies included investigations of NNESTs’ professional identities as language practitioners (e.g., Johnson, Reference Johnson2001). That is, if we consider those conversations as a research and advocacy response to the impact of the ideologies of “native speakerism” on teachers’ practice, learning, and identities, the research base has always been interested in the complex relationship between teachers’ linguistic and professional identities. The endeavors to understand that complex relationship were more explicitly articulated as more researchers started using “teacher identity” as a conceptual lens to make sense of teachers’ learning and growth (e.g., Rudolph et al., Reference Rudolph, Selvi and Yazan2020; Varghese et al., Reference Varghese, Motha, Park, Reeves and Trent2016). The use of that lens has led NNEST literature to open different conceptual directions with variable degrees of criticality. In this subsection, we discuss those directions and their implications for the future of the scholarship that attends to NNESTs’ professional lives from an LTI perspective.

First, (non)nativeness is such a slippery and evasive concept that using it to define a language user's or professional's linguistic identity is problematic, since linguistic identities are more complicated than this dichotomous nomenclature can capture (Ellis, Reference Ellis2016; Faez, Reference Faez2011a, Reference Faez2011b; Holliday & Aboshiha, Reference Holliday and Aboshiha2009). The ideologies of (non)nativeness still prevalently divide ELT professionals into two imaginary groups (Huang, Reference Huang2014; Huang & Varghese, Reference Huang and Varghese2015; Kim, Reference Kim2011; Kramsch & Zhang, Reference Kramsch and Zhang2018; Reis, Reference Reis2011, Reference Reis2012). Language teachers are exposed to and respond to those ideologies variably in their professional lives. For example, in Park (Reference Park2012), Xia defied the ideologies of (non)nativeness with the support of her mentor teacher (who also identified as NNEST) and transformed her teacher identity (inseparable from her learner identity in that case) from the deficit way of identifying herself as less than a “NEST.” Viewing herself as a bilingual NNES, Xia learned to deploy her identity to “utilize cultural and linguistic experiences in crafting her teaching pedagogy, coupled with addressing the needs of her students” (p. 140). Park (Reference Park2012) indicates that language teachers pour different meanings and values into the categories of NEST/NNEST. Regardless of whether they self-identify or are categorized as either NEST or NNEST or neither in their contexts, it is imperative to note that language is the content taught as opposed to any other academic subject matter. Especially in the case of NNESTs, this generalization would hold true most of the time: NNESTs teach a language they learned most likely in a school setting, in addition to/alongside their home languages, and their experiences of that learning could be reasonably recent or memorable compared to the learning of their other languages. In NNESTs’ lives, both as teachers and former learners of English, language has been the curriculum content, the medium of instruction, and the social practice they perform. Therefore, the English language as an identity marker is such an easily discernible and significant one for NNESTs in their professional life. The same is true for NESTs. That is, NEST or NNEST, their linguistic identity, which is already complex in and of itself, is inseparable from their professional identity. This relationship has been one of the significant precursors in the expansion of LTI research initially, and, in return, the LTI approach to NESTs’/NNESTs’ experiences afforded new ways of conceptualizing their situatedness within sociocultural discourses and of explicating the connection between the language classroom and beyond.

Second, Moussu and Llurda's (Reference Moussu and Llurda2008) call to attend to the diversity within NNESTs has been responded to with the LTI lens. That is, scholars brought in new critical theoretical perspectives such as intersectionality, critical race or feminist theory, postcolonial theory, and poststructuralist theory and attended to the other dimensions of NEST/NNESTs’ professional identities (in addition to the linguistic one). This research with the LTI lens provided new understandings of how the ideologies of nativeness shape and are shaped by (are in constant interplay with) the ideologies of race, ethnicity, nationality, gender, sexuality, among others. The central assumption and finding in that strand of research is that capturing a complete picture of NESTs/NNESTs’ professional identities requires focusing on multiple facets of their identities vis-à-vis social identity categories. Particularly, ideologies of race and processes of racialization have been an important topic in further understanding teacher identities in relation to (non)nativeness (Amin, Reference Amin1997; Holliday & Aboshiha, Reference Holliday and Aboshiha2009; Motha, Reference Motha2006; Ramjattan, Reference Ramjattan2019a; Ruecker, Reference Ruecker2011; Von Esch et al., Reference Von Esch, Motha and Kubota2020). For example, Park's (Reference Park2009) qualitative study examines the identities of a woman TESOL teacher candidate (Han Nah) from Korea by analyzing her experiences in Korean, Turkish, and US education systems. Park finds that Han Nah's professional identity was intertwined with her gendered, racial, and linguistic identities and was in constant connection in relation to the macro-social context in which teaching-learning takes place. Also, in their duoethnography, Lawrence and Nagashima (Reference Lawrence and Nagashima2020) examine the intersections between personal and professional identities to better understand their own teacher identities in the educational context of Japan. Their study found that their teacher identities are situated at the nexus of their gender, sexuality, race, and linguistic status (NEST vs. NNEST).

Third, the new conceptual approaches resonate with the earlier calls (Cook, Reference Cook1999; Pavlenko, Reference Pavlenko2003, among others) for using more inclusive names/labels that can better capture the complexity of ELT professionals’ linguistic identities. As we discussed earlier in this article, scholars intentionally pushed the boundaries of naming to foreground ELT professionals’ wealth of linguistic repertoires, which are not reflected in the nomenclature based on the ideologies of (non)nativeness. Interacting with the “multilingual turn” (Conteh & Meier, Reference Conteh and Meier2014; May, Reference May2014) in language education, research on NNESTs began framing the teachers’ linguistic identities as “multilingual” (Kirkpatrick, Reference Kirkpatrick2008), “multicompetent plurilingual” (Ellis, Reference Ellis2016), “translingual” (Ishihara & Menard-Warwick, Reference Ishihara and Menard-Warwick2018; Lee & Canagarajah, Reference Lee and Canagarajah2019; Motha et al., Reference Motha, Jain and Tecle2012; Zheng, Reference Zheng2017), and “transnational” (Jain et al., Reference Jain, Yazan and Canagarajah2021; Menard-Warwick, Reference Menard-Warwick2008; Solano-Campos, Reference Solano-Campos2014; Yazan et al., Reference Yazan, Canagarajah and Jain2021). For example, based on her research with ELT professionals from a variety of educational contexts, Ellis (Reference Ellis2016) advocates for more emphasis on all language teachers’ “languaged lives” (p. 599) that help them fashion their linguistic identities and deploy them as “linguistic identities as pedagogy” (p. 622). Her study resonated with the earlier research in that the NEST/NNEST dichotomy is restricted and restrictive in describing language teachers’ linguistic identities. Her findings confirm Faez's work (Reference Faez2011a, Reference Faez2011b) and make a solid case to describe all ELT professionals as “multicompetent plurilinguals” by highlighting the entirety of their linguistic repertoires as part of their linguistic identities.

Fourth, the new conceptual approaches with LTI also destabilized the understanding of privilege and marginalization that NESTs and NNESTs experience. Initially, the NNEST literature grew as a reaction against the assignment of ideologies around native speaker fallacy, privilege, and marginalization to the NESTs and NNESTs in a categorical and universal fashion (Yazan & Rudolph, Reference Yazan and Rudolph2018; see introduction). That is, all NESTs were positioned as privilege-holders owing to their native speaker status, while all NNESTs were viewed as marginalized owing to their non-native speaker status. This clean-cut binary perspective was questioned and complexified through research attempts at theorizing and analyzing the connections between language and other social identities (e.g., race, ethnicity, gender, nationality) in NNESTs’ professional identities. That research led to such productive questions: Are NNESTs marginalized because of their race in addition to their language? Are some NNESTs marginalized more than others because of their race, ethnicity, or gender? Are some NESTs marginalized because of their race? Are some NESTs marginalized because they do not speak the dominant language of the local context? Are some NESTs marginalized because they are “foreigners”? Are some NESTs/NNESTs marginalized by the prevalent gender discourses in the local context? Those questions directed attention to the need to come up with a more nuanced theorization of privilege and marginalization experienced by ELT professionals in their teaching contexts which are shaped by social, cultural, political, and historical discourses. For example, in her study focusing on the transnational experiences of two East Asian women, Park (Reference Park2015) explores the complexities of marginalization and privilege in these women's identities at the intersection of language, race, gender, and class. In another study attending to the complexity and fluidity of privilege and marginalization, Charles (Reference Charles2019) examines the teaching experiences of two Black teachers of English (Jamie and Nancy) in secondary education in South Korea by using critical race theory as her theoretical approach and narrative inquiry as a method. Both teachers constructed the identity of a cultural ambassador, but the ideologies of nativeness and race have influenced how they were positioned in that education context. Nancy, for instance, “was privileged to be a resource that taught students about circumstantial events that occur in some U.S. cities,” whereas she “was also marginalized in being pigeonholed as the expert to discuss crime in U.S. cities, since students ascribed crime and gun culture to her culture as a Black American” (p. 12).

Fifth, the LTI lens in the NNEST research helped scholars make explicit the connection between teachers’ past language (learning) experiences (what Ellis [Reference Ellis2016] calls “languaged lives”) and ongoing identity work in their professional lives. The NNEST research has attended to teachers’ past experiences to examine the marginalization they have been exposed to or the ways in which they can support language learners by relying on their own learning experiences often shared with the learners. The LTI lens framed this attention with the concept of identity (with emphasis on “continuity/discontinuity,” see Akkerman & Meijer, Reference Akkerman and Meijer2011) by foregrounding the inseparability between past identities as a learner and user of English with the current identity of an English teacher. In LTI research, teachers’ personal biographies and how they interpret and reinterpret them are significant components in teachers’ current understandings of who a “good” language teacher is and should/can be and what kind of teacher they are and should/can be. Bringing that assumption into researching NNESTs’ professional identities, scholars not only established a conceptual relationship between lived experiences and current linguistic identities but also found how other dominant ideologies (in tandem with or in lieu of [non]nativeness) have influenced who they are as ELT professionals at present. For example, Rudolph et al. (Reference Rudolph, Yazan and Rudolph2019) present a narrative inquiry of two ELT professionals that focused on their educational trajectory, including border-crossing experiences as learners and teachers. The authors found how ideologies of sexism/misogyny and colonialism have deeply impacted two ELT professionals, especially when they work as teachers in a Japanese higher education context. Although their past experiences involved (non)nativeness as one dimension, more important was their struggles with the broader cultures of oppression.

Lastly, in the NNEST literature, language teachers’ emotional struggles have been an important topic that scholars addressed by following the assumption that hierarchies constructed through the ideologies of (non)nativeness positioned NNESTs as “less than” or “not-legitimate enough.” More studies emerged following Moussu and Llurda's (Reference Moussu and Llurda2008) review, and they mostly used LTI as a conceptual lens that theorized emotions in relation to the professional identity work in which teachers engage in and outside the classroom. For example, Reis's (Reference Reis2012, Reference Reis, Cheung, Said and Park2014) work has explored the impact of NNESTs’ emotional experiences on their professional legitimacy and teacher identity. Additionally, in her research, Song (Reference Song2016a, Reference Song2016b) more specifically foregrounds the premise that teacher identity work is an emotional experience and explores NNESTs’ emotions and identities in their stories about “their own competence, desires, and school curriculum” (Song, Reference Song2016b, p. 635) by using Zembylas's (Reference Zembylas2003) concept of “emotional rules.” The ideologies of (non)nativeness, dominant in the Korean education system, were significant in teachers’ stories, and their identity negotiation was guided by the ways in which they dealt with emotional struggles. However, in both empirical studies, (non)nativeness was significant in data but not the primary focus of her studies. In a later conceptual work, Song (Reference Song2018) theorizes emotions, especially anxiety, in NNESTs’ professional life with critical approaches. She explains NNESTs’ anxiety and other emotional struggles by focusing on the ideological hierarchies constructed through and within dominant discourses.

4.2 Theoretical expansion of the identity, status, and empowerment of language teachers

Until the past decade, the status and empowerment of ELT professionals often revolved around (at least) three prominent theoretical constructs.Footnote 3 These are: (1) Phillipson's (Reference Phillipson1992) formulation of “linguistic imperialism,” which brought about the “native speaker fallacy,” defined as “the belief that the ideal teacher of English is a native speaker” (p. 127); (2) Widdowson's (Reference Widdowson1994) critique of the “ownership of English,” which destabilized the prevalent assumptions and links between the English language and nation-states; and (3) Holliday's (Reference Holliday2005) concept of “native speakerism,” which referred to “an established belief that native-speaker teachers represent a ‘Western culture’ from which springs the ideals both of the English language and of English language teaching methodology” (p. 6). Scholars using these theoretical lenses problematized the values, beliefs, and practices that normalize “automatic extrapolation from competent speaker to a competent teacher based on linguistic grounds alone” (Seidlhofer, Reference Seidlhofer1999, p. 236). Furthermore, they employed these theoretical lenses to highlight the relative advantages and contributions of both NESTs and NNESTs (e.g., Árva & Medgyes, Reference Árva and Medgyes2000; Moussu, Reference Moussu and Liontas2018a, Reference Moussu and Liontas2018b), to call for collaboration and collaborative practices in ELT (e.g., de Oliveira & Clark-Gareca, Reference de Oliveira, Clark-Gareca and Martínez Agudo2017; Oda, Reference Oda and Liontas2018), and to problematize recruitment practices (e.g., Jenks, Reference Jenks2017; Ma, Reference Ma2012a; Ruecker & Ives, Reference Ruecker and Ives2015).

Over the past decade, these constructs continued to serve as theoretical lenses to examine lives, practices, and policies surrounding ELT professionals around the world. (e.g., Kim, Reference Kim2011; Lowe & Kiczkowiak, Reference Lowe and Kiczkowiak2016). More interestingly, scholars began formulating new theoretical concepts to expand the current research base and to inform advocacy initiatives focusing on NESTs and NNESTs, as follows:

• “(non)native speakering” (Aneja, Reference Aneja2016a), referring to how race (and raciolinguistic ideologies) is used as a proxy in understanding “historical origins and continuous (re)emergence of native and nonnative positionalities” (p. 353);

• “non-native speaker fallacy” (Selvi, Reference Selvi2014) and “nonnative speakerism” (Selvi, Reference Selvi, Uştuk and De Costain press), both referring to the reverse status quo captured by “the idealization and promotion of teachers who are positioned or self-described as ‘nonnative speakers’ as more viable models of learning and teaching”;

• “native speaker saviorism” (Jenks & Lee, Reference Jenks and Lee2020), referring to an “arbitrarily sedimented racialized hierarchy in which actions and behaviors associated with Whiteness are viewed as normative practices and aspirations” (p. 190);

• “pseudo-native speakerism” (Tezgiden Cakcak, Reference Tezgiden Cakcak2019), used to define professionals who are asked to lie about their personal and linguistic backgrounds and to behave as if they are monolingual NESTs; and

• “beyond (non)native speakerism” (Houghton & Rivers, Reference Houghton and Rivers2013; Leonard, Reference Leonard2019) and “post-native-speakerism” (Houghton & Hashimoto, Reference Houghton and Hashimoto2018), both of which challenge us (and the field) to envision and build a professional landscape and practices (both at macro and micro levels) conducive to the dynamic sociolinguistic realities of language use and instruction within and beyond the ELT classroom.

Scholars adopted critical approaches to understanding, theorizing, and deconstructing myriad issues of power and inequality vis-á-vis linguistic identities of ELT professionals and found existing theoretical constructs somewhat limiting and problematic. Therefore, they ventured into new territories to shed more contemporary light on such issues.

The second paradigmatic model, offered by Galloway and Rose (Reference Galloway and Rose2015), is Global Englishes, which brought together World Englishes (WE), English as an International Language (EIL), and English as a Lingua Franca (ELF) research traditions (as well as similar movements in SLA, such as translanguaging and the multilingual turn) to “explore the linguistic, sociolinguistic, and sociocultural diversity and fluidity of English use and the implications of this diversity of English on multifaceted aspects of society, including TESOL curricula and English language teaching practices” (Rose et al., Reference Rose, McKinley and Galloway2021, p. 158). Research and pedagogical frameworks within Global Englishes (e.g., WE-informed ELT [Matsuda, Reference Matsuda, Nelson, Proshina and Davis2020], the EIL Curriculum Blueprint [Matsuda & Friedrich, Reference Matsuda and Friedrich2011], ELF-aware pedagogy [Bayyurt & Sifakis, Reference Bayyurt, Sifakis and Vettorel2015], and Global Englishes Language Teaching [Rose & Galloway, Reference Rose and Galloway2019]) share a common goal and ideology promoting a meaningful “epistemic break” from the idealized native speaker norms and instigating action-oriented advocacy (Kumaravadivelu, Reference Kumaravadivelu2012, Reference Kumaravadivelu2016). The most significant contribution of this paradigm is the recontextualization of the issue of teacher identity and legitimacy within a broader and more systematic framework calling for a paradigm shift that envisions ELT (both as a profession and as an activity) detached from the idealized native speaker norms determining qualities and qualifications of a legitimate ELT professional. Moreover, studies on teacher identity through a Global Englishes lens also aim to instill criticality and critical dispositions on professional identity (navigating the fluidity and complexity of privilege and marginalization in the negotiation and [re]construction of their professional identities) and promote teacher identity, legitimacy, status, and respect (e.g., Widodo et al., Reference Widodo, Fang and Elyas2020; Zacharias, Reference Zacharias2019). On the other hand, Global Englishes scholars recognize the rigidity and prevalence of potential barriers to change and innovation in ELT, including inequitable hiring practices (see Galloway & Rose, Reference Galloway and Rose2015), the slow pace, and other local constraints connected to teachers’ personalities and broader sociocultural contexts therein (Prabjandee, Reference Prabjandee2020).

Collectively, these established and novel theoretical perspectives are powerful testaments to the ongoing interest in this line of inquiry, expansion of the theoretical boundaries, and new insights into future directions. Therefore, we need more guidance for junior scholars (as a point of entry), policymakers, administrators, and/or institutions (as a point of transformation and implications), and both junior and established scholars (as a future direction of investigation) and advocacy-oriented bodies (as a reflection of success and further growth).

4.3 Perceptions of major stakeholders in ELT: Relative and comparative (dis)advantages of “NESTs” and “NNESTs”

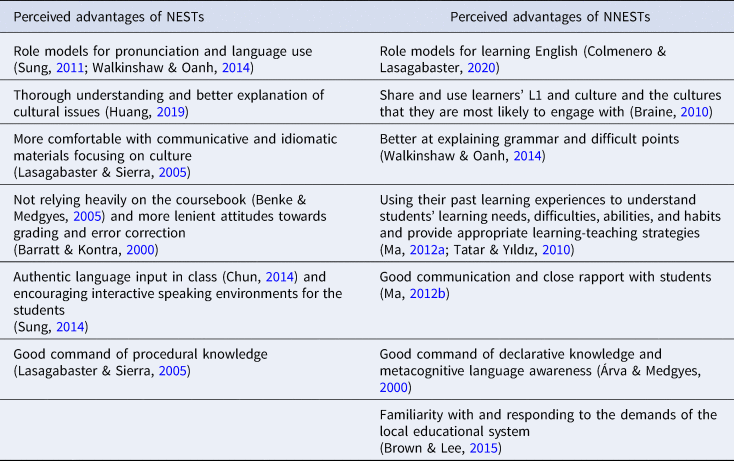

Even though the demarcation between NESTs and NNESTs is found to be artificial, ideological, and highly problematic today, the relative and comparative strengths and weaknesses of NESTs and NNESTs have always, since the early days, spurred interest among the researchers working in this line of inquiry (Medgyes, Reference Medgyes1992, Reference Medgyes1994). This interest is primarily based on the “two different species” position (Medgyes, Reference Medgyes1994), which argues that “NESTs and non-NESTs use English differently and, therefore, teach English differently” (p. 346) (see also Medgyes's list of six unique assets of NNESTs). Moreover, this position carries significant implications for ELT professionals – the overreliance on the terms of NEST and NNEST as dichotomous categories of identity, juxtapositions of instructional qualities and qualifications, the reification of the stereotypical division of labor in educational institutions (e.g., NESTs for productive skills and NNESTs for receptive skills), and essentialization of personal/professional histories (e.g., NNESTs are multilingual “insiders” with absolute authority on the local, sharing the same linguacultural background with students, whereas NESTs are monolingual and perpetual “outsiders” with no connections with the student at the linguacultural levels) (Selvi, Reference Selvi2014). However, scholars continued to highlight the relative and comparative (dis)advantages of NESTs and NNESTs (see Table 3 for a summary) for (at least) three main reasons: (a) construing the legitimacy of NNESTs to be used in fighting against discriminatory workplace and hiring practices (and promoting employability in the profession), (b) making a better case for collaboration and collaborative practices, and (c) empowering both groups of teachers (Moussu, Reference Moussu and Liontas2018a, Reference Moussu and Liontas2018b).

Table 3. Perceived advantages of NESTs and NNESTs: A compilation of the literature

The overview of the literature is enlightening in several ways. First, it showcases the ongoing interest in the relative and comparative advantages of NESTs and NNESTs. Second, “the different but complementary capacities from these two groups of teachers” (Rao & Chen, Reference Rao and Chen2020, p. 333) leads to juxtaposed and mutually exclusive comparisons and decontextualized generalizations about what and how a teacher can/cannot, should/should not be and behave. Understanding the advantages of teachers (regardless of any background) is a complex and socioeducationally situated endeavor. Third, and as a corollary, stakeholders in ELT (e.g., students, teachers, administrators, parents, among others) feel compelled to make mutually exclusive decisions of preferences (see the next section) and to take sides with a category of identity as a result of decontextualized, essentialized, and homogenized judgments. Fourth, the complementary distribution of instructional strengths stands out as the primary motivation behind: (a) stereotypical division of labor in ELT institutions, (b) discrimination and discriminatory practices in hiring and workplace settings, and (c) construction of collaboration and collaborative practices, such as the team-teaching/co-teaching schemes predominant in Asia (e.g., JET in Japan, NET in Hong Kong, EPIK in South Korea, and FET in Taiwan). Fifth, the literature on (dis)advantages of ELT professionals is often contradictory (e.g., Aslan & Thompson, Reference Aslan and Thompson2017; Inbar-Lourie & Donitsa-Schmidt, Reference Inbar-Lourie and Donitsa-Schmidt2020). For all these reasons combined, interested readers and scholars must approach this line of inquiry both cautiously and critically.

4.4 Preference toward NESTs and NNESTs and its professional consequences

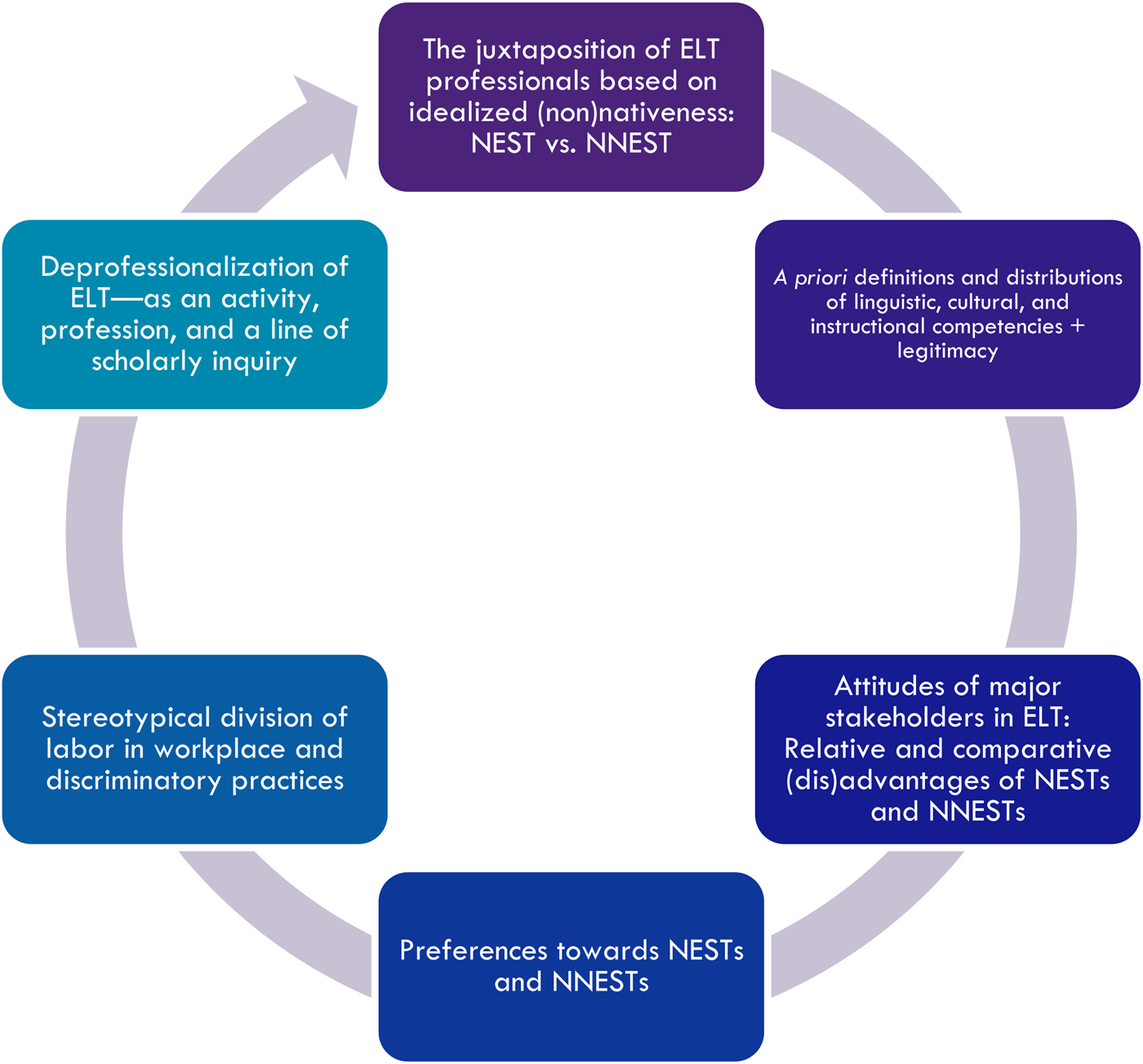

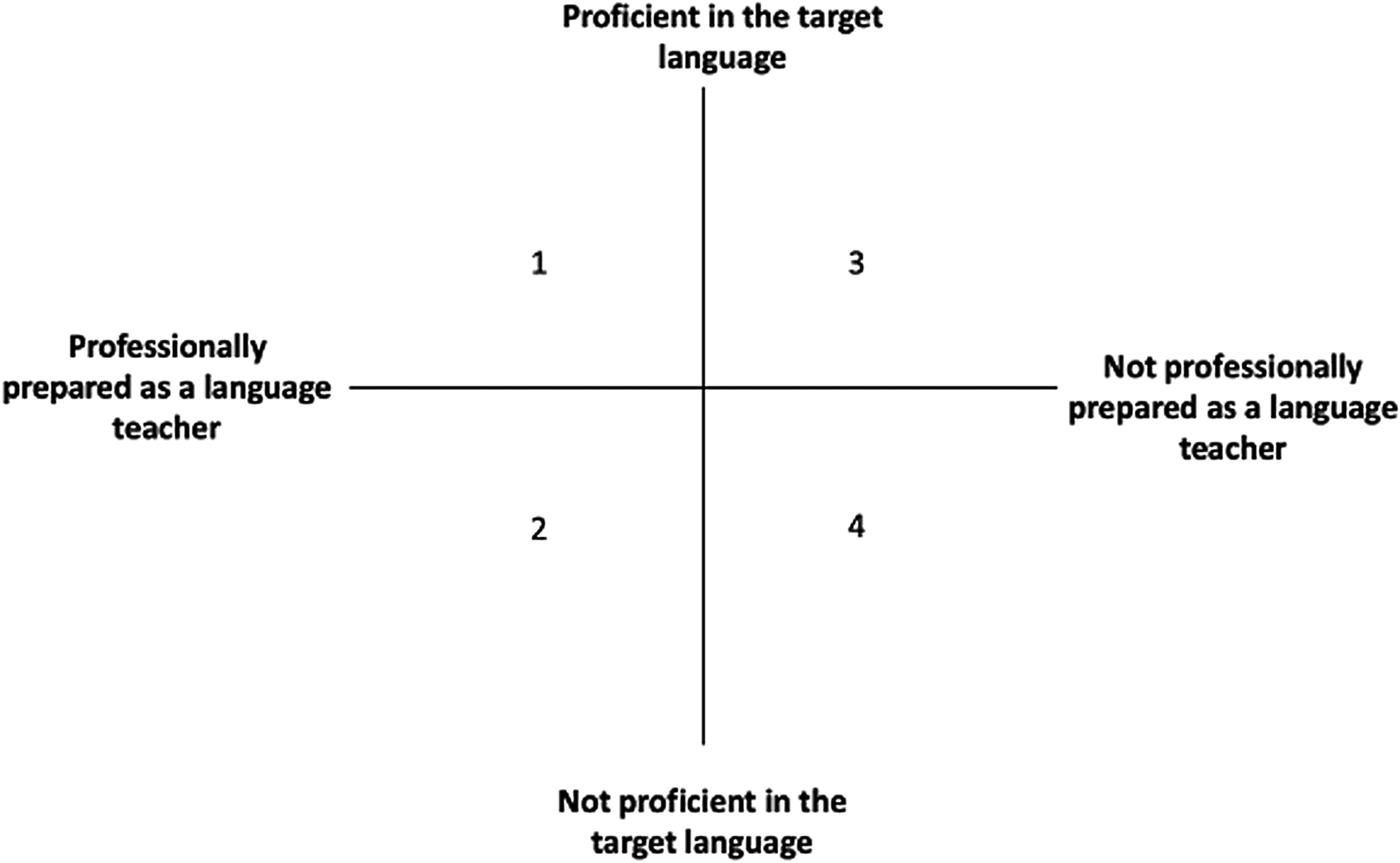

The demarcation of ELT professionals as mutually exclusive and juxtaposed categories of identity (i.e., NESTs and NNESTs) with their own idiosyncratic (dis)advantages results in the prevalence of ideologies, discourses, and practices damaging the overall professional stature of the ELT profession (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. The consequences of the prevalent juxtaposition of ELT professionals based on idealized nativeness

More important, operating in a professional ecosystem whose core values are shaped by such value-laden divisions, major stakeholders often feel compelled to externalize stance (i.e., attitudes) and behaviors (i.e., preferences) toward ELT professionals, which ultimately connect the dots about their qualities, qualifications, and legitimacy as teachers. Consequently:

• teachers may begin making judgments of their professional selves, questioning their legitimacy, personal/professional self-esteem, and even in-class performance through a set of discourses such as “inferiority complex” (Medgyes, Reference Medgyes1994), “I-am-not-a-native-speaker syndrome” (Suarez, Reference Suarez2000), “Stockholm syndrome” (Llurda, Reference Llurda and Sharifian2009), or “impostor syndrome” (Bernat, Reference Bernat2008);

• students seem to idealize “nativeness” as an index for authenticity and authority (Lowe & Pinner, Reference Lowe and Pinner2016), a gateway for successful teaching, and a model and target for learning (Alseweed, Reference Alseweed2012);

• parents (especially when they do not speak English themselves) invest in their children's language development by extrapolating from language expertise (i.e., often equated to “NSs”) to language teaching expertise (i.e., thereby, “NESTs”) (Colmenero & Lasagabaster, Reference Colmenero and Lasagabaster2020; Sung, Reference Sung2011); and

• administrators may use all the arguments above as a springboard to create a “supply-demand” argument serving as a “customer-driven” justification for discriminatory practices in hiring processes and workplace settings (Selvi, Reference Selvi2014).

Main stakeholders in ELT, particularly students (e.g., Subtirelu, Reference Subtirelu2013) and parents (e.g., Colmenero & Lasagabaster, Reference Colmenero and Lasagabaster2020; Sung, Reference Sung2011), exhibit a preference for NESTs over NNESTs in the teaching and learning of aural skills (listening and pronunciation/speaking) (e.g., Chen, Reference Chen2008; Walkinshaw & Oanh, Reference Walkinshaw and Oanh2012; Watson Todd & Pojanapunya, Reference Watson Todd and Pojanapunya2009) and the attainment of “authentic” models of the language (Lowe & Pinner, Reference Lowe and Pinner2016) and cultural knowledge (e.g., Lasagabaster & Sierra, Reference Lasagabaster and Sierra2005), especially as their proficiency level increased (e.g., Levis et al., Reference Levis, Sonsaat, Link and Barriuso2016; Madrid & Cañado, Reference Madrid and Cañado2004) in various contexts in Asia (e.g., Chun, Reference Chun2014; Huang, Reference Huang2019; Sung, Reference Sung2014; Trent, Reference Trent2012; Tsou & Chen, Reference Tsou and Chen2019), the Middle East, (e.g., Buckingham, Reference Buckingham2014), Europe (e.g., Lasagabaster & Sierra, Reference Lasagabaster and Sierra2005) and the U.S. (e.g., Aslan & Thompson, Reference Aslan and Thompson2017; de Figueiredo, Reference de Figueiredo2011).

While this treatment of NESTs may be an extension of the broader literature on perceptions (and therefore sound “intuitive” for some), it does not do any justice to understanding the tensions, complexities, and contradictions embedded in the literature. First and foremost, while some studies reported a clear preference for NESTs over NNESTs (e.g., Alseweed, Reference Alseweed2012; Karakaş et al., Reference Karakaş, Uysal, Bilgin and Bulut2016; Rao, Reference Rao2010; Tsou & Chen, Reference Tsou and Chen2019), others reported no significant differences (e.g., Aslan & Thompson, Reference Aslan and Thompson2017; Chun, Reference Chun2014; Guerra, Reference Guerra and Martínez Agudo2017; Han et al., Reference Han, Tanrıöver and Şahan2016; Inbar-Lourie & Donitsa-Schmidt, Reference Inbar-Lourie and Donitsa-Schmidt2020; Lipovsky & Mahboob, Reference Lipovsky, Mahboob and Mahboob2010; Wang & Fang, Reference Wang and Fang2020), even an inability to differentiate between them (e.g., Ali, Reference Ali and Sharifian2009). In cases where the problematic construct of (non)nativeness is taken out of the equation, stakeholders based their preference on pedagogical skills and characteristics such as extensive declarative and procedural knowledge of the English language (Mullock, Reference Mullock and Mahboob2010). Second, learners’ perceptions of relative and comparative (dis)advantages of the two may not always lead to their preferences based on this perspective. Yeung (Reference Yeung2021) argued that “perceptions and preferences, while akin to each other, could be discussed or treated as two distinct concepts in explaining people's choices” (p. 66). To exemplify, in a study with Chinese students, participants exhibited a clear preference toward NESTs, despite their perceived unfamiliarity with students’ language-related problems, educational backgrounds, and local culture (Rao, Reference Rao2010). Third, the preference literature also spurred a recent interest in understanding the impact of teachers on students’ learning (e.g., Alghofaili & Elyas, Reference Alghofaili and Elyas2017; Pae, Reference Pae2017; Schenck, Reference Schenck2018). The recent findings indicate that students’ preferences did not have an impact on their motivation to learn English (Pae, Reference Pae2017). While Schenck (Reference Schenck2018) reported a positive impact of NESTs on lexical sophistication of speech, Levis et al. (Reference Levis, Sonsaat, Link and Barriuso2016) argued that there is no causal relationship between NESTs and better pronunciation (and NNESTs and worse pronunciation). Fourth, parallel to the recent expansion of English as the medium of instruction (EMI) practices and explorations, scholars examined the impact of teachers’ linguistic identity. Interestingly, students exhibited a preference for native English-speaking EMI instructors (e.g., see Inbar-Lourie and Donitsa-Schmidt [Reference Inbar-Lourie, Donitsa-Schmidt, Doiz, Lasagabaster and Sierra2013] for Israel, Jensen et al. [Reference Jensen, Denver, Mees and Werther2013] for Denmark, and Karakaş [Reference Karakaş2017] for Turkey) as a gateway for improving their English proficiency even though this language focus is often ignored by the instructors (Airey, Reference Airey2012) and valued less as compared with context expertise (Coleman et al., Reference Coleman, Hultgren, Li, Tsui and Shaw2018) and international expertise (Inbar-Lourie & Donitsa-Schmidt, Reference Inbar-Lourie and Donitsa-Schmidt2020).

As we explore the preference literature (and related trends) in the context of current debates about NESTs and NNESTs, we come to the same conclusion: the literature is complex, multifaceted, messy, inconclusive, and often contradictory. Furthermore, the problem with the preference literature manifests itself at (at least) two distinct yet interrelated levels. Ideologically, the notion of preference reduces individual characteristics and pedagogical qualities and qualifications into a construct (NEST/NNEST) encapsulating monolingual ideologies and linguistic hierarchies (Rudolph et al., Reference Rudolph, Selvi and Yazan2015). Methodologically, it is characterized by conflicting and contradictory results and makes decontextualized and universalized generalizations about a category of teachers based on a small group of participants.

4.5 Alternative terms for language teachers’ linguistic identities: What's in a name?

NS and NNS (and their extensions, NEST and NNEST) have been widely employed in the ELT and language teacher education literature and professional settings worldwide. As these terms gained traction over time, so did criticisms of them. Initially, these criticisms gravitated to the unquestionable universal supremacy of NS as the ideal speaker with an absolute proficiency living in a completely homogeneous linguistic environment. Recognizing the theoretical insufficiency and practical consequences of this term, scholars offered some alternatives to NS (e.g., “proficient user of English,” [Paikeday, Reference Paikeday1985], “more or less accomplished users of English” [Edge, Reference Edge1988], “language expert” [Rampton, Reference Rampton1990], “English-using speech fellowship” [Kachru, Reference Kachru1992], and “competent users” [Holliday, Reference Holliday and Sharifian2009], among others). Concomitantly, others adopted a similar strategy to resist a native speakerist orientation to expertise and/or language proficiency by offering alternatives to NNS (e.g., “bilingual speakers” [Jenkins, Reference Jenkins1996], “multicompetent speaker” [Cook, Reference Cook1999], and “L2 user” [Cook, Reference Cook2002], among others).

Even though the idealized NS is “an abstraction with no resemblance to a living human being” (Braine, Reference Braine and Kamhi-Stein2004, p. xv), this construct forms the basis and extrapolation of idealization from linguistic expertise to pedagogical expertise. When combined with the other dimensions (e.g., race, ethnicity, gender, physical appearance, localness, among others), this premise serves as the bedrock of discrimination and discriminatory practices. Recognizing the problematic and contested nature of these terms, scholars created new terms as alternatives to NNESTs in the past two decades (see Table 4).

Table 4. Alternative labels to “NNEST”: A review of the literature (in chronological order)

The motivation behind new descriptors is twofold: First, they create more neutral and liberatory spaces by moving away from formulations defining teachers based on the other (i.e., NEST) using a deficit perspective (i.e., with the “non-” prefix). Second, they either foreground teachers’ strengths (e.g., multicompetent, bilingual/multilingual/plurilingual, etc.) or underscore their complex sociolinguistic experiences and identities as language users and professionals (e.g., transnational, translingual, etc.). Even though these alternative terms may not serve as direct replacements for the existing terms or the problematic demarcation among ELT professionals and may even lead to problematic associations (e.g., NESTs as monolingual; see Ellis, Reference Ellis2016), they are powerful in reflecting tensions, complexities, and diversity within the field through various alternative or imagined identity options (Jain, Reference Jain2014). Soon, we envision that the quest for new professional spaces for ELT professionals will continue with more additions that highlight all-encompassing common denominators capturing diversity within ELT professionals – experience, expertise, and professional development.

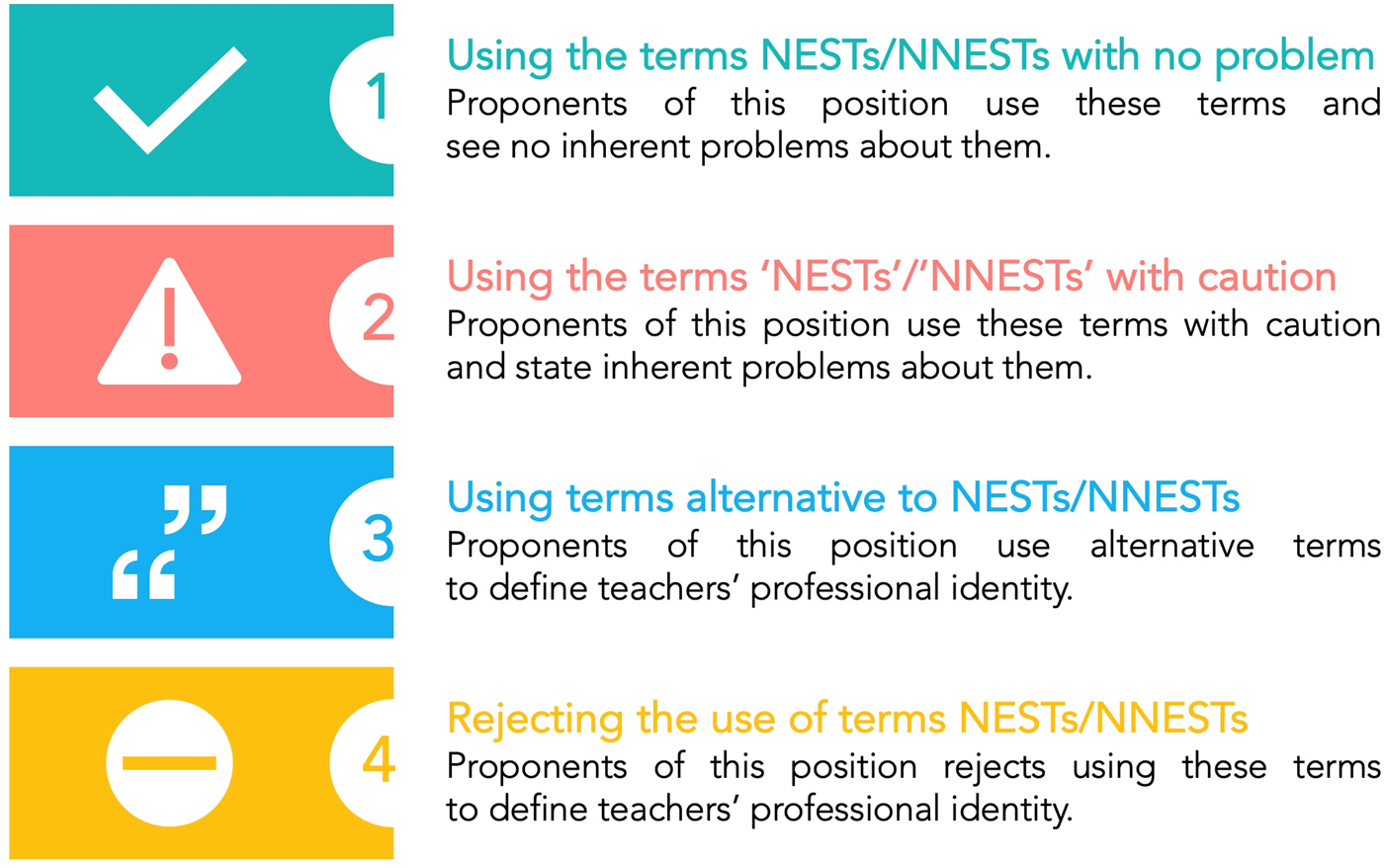

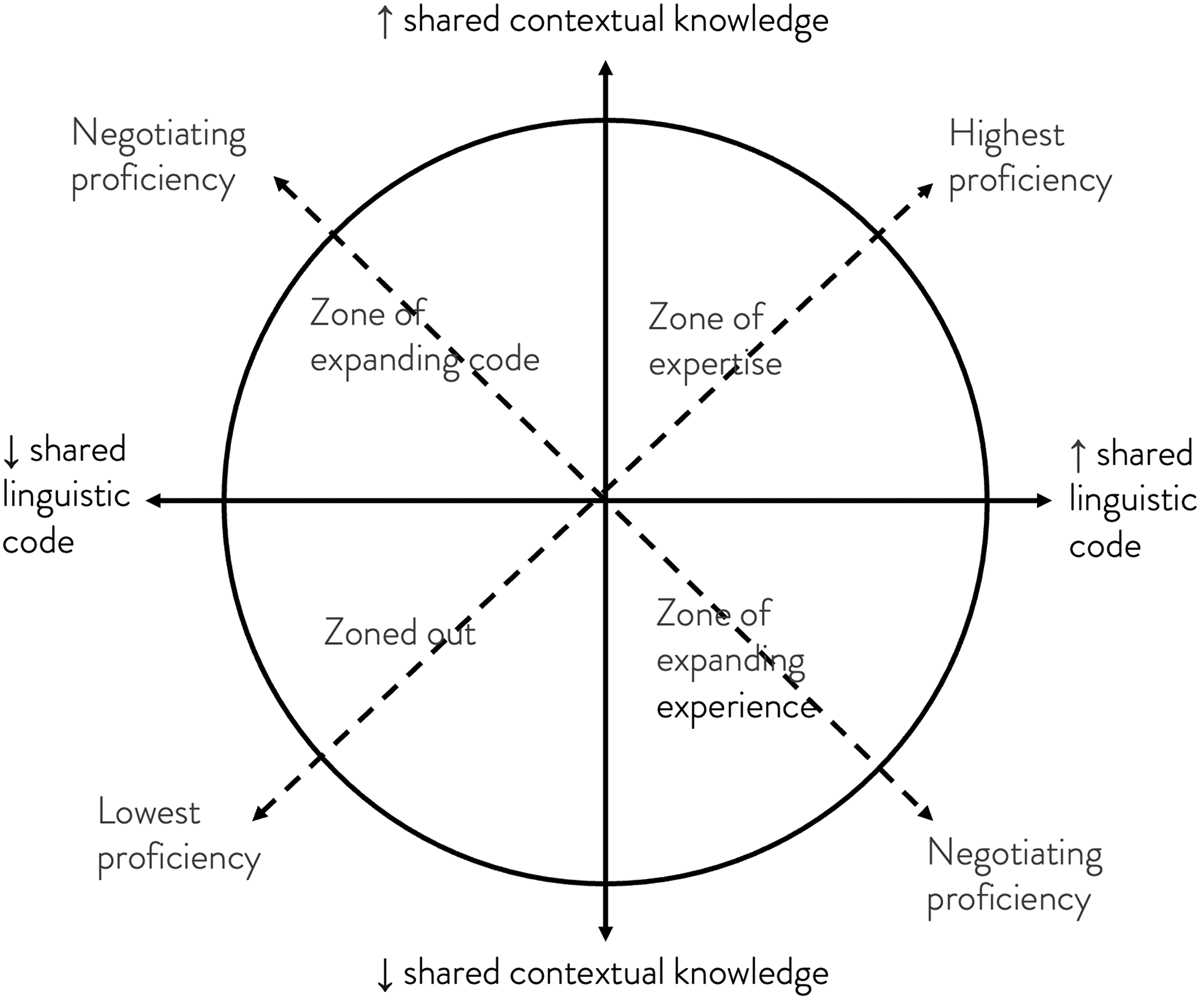

The nomenclature debate affords a powerful lens to examine various ideological positions on using the NEST/NNEST terms in the ELT field. As summarized in Figure 3, most ELT professionals rely on these terms, which adds to the reification of a professional discourse around these notions, avoidance of the structures of inequity, marginalization, and discrimination, and struggles of advocacy and resistance. Others rely on these terms with caution, often indexed by the consistent uses of inverted commas (Holliday, Reference Holliday, Swan, Aboshiha and Holliday2015) but recognize and justify the ideological, discoursal, professional, and practical implications of their use. As delineated above, a growing number of scholars use the nomenclature debate as an intellectual springboard to create new terms that recognize the diversity within ELT professionals. Finally, an increasing number of critically oriented scholars reject the use of these terms owing to their insufficiency in addressing the complexities embedded in personal/professional identity and interaction and making universalized/essentialized statements about ELT professionals.

Figure 3. Four ideological positions on the NEST/NNEST nomenclature debate (based on Selvi, Reference Selvi2014, Reference Selvi, Mann and Walsh2019b)

4.6 Discrimination and discriminatory practices in hiring and the workplace

The theoretical discussions on legitimacy and power enacted through the valorization of “standard English” and particular dialects (and their users) and stigmatization of others (and their users) (Lippi-Green, Reference Lippi-Green2012) have real-life consequences for millions of ELT professionals who are un/willingly subjected to this artificial polarity as a category of linguistic (as in NS/NNS) and professional (as in NEST/NNEST) identity. For this reason, employability and recruitment as “a form of gatekeeping to the teaching profession” (Alshammari, Reference Alshammari2021), or “the elephant in the room” (Jenkins, Reference Jenkins2017, p. 373), has been a prominent focus informing research efforts and advocacy practices in this area. A quick look at the current scholarship reveals several important findings and future directions:

1. First and perhaps most disturbingly, despite anti-discrimination laws and the ongoing professional responses (e.g., BC TEAL, 2014; CATESOL, 2013; TESOL, 1992, 2006; TESOL Spain, 2016) proscribing any unfair and unequal treatment based on linguistic and non-linguistic grounds, today, the ELT profession is still characterized by blatant or subtle discrimination and discriminatory practices in hiring processes, salary, and in the workplace. Collectively, such forms and contexts serve as manifestations that normalize discrimination through institutionalized practices, weave them into the fabric of the ELT profession, and define professional benchmarks and realities for ELT professionals.

2. Research to date has confirmed the omnipresence of idealized native speakerism as the most salient discriminatory dimension in hiring practices in ELT in the Middle East and Asia (e.g., Alshammari, Reference Alshammari2021; Doan, Reference Doan2016; Mahboob & Golden, Reference Mahboob and Golden2013; Ruecker & Ives, Reference Ruecker and Ives2015; Selvi, Reference Selvi2010; Wang & Lin, Reference Wang and Lin2014), North America (e.g., de Figueiredo, Reference de Figueiredo2011; Ramjattan, Reference Ramjattan2019b), the U.K. (e.g., Clark & Paran, Reference Clark and Paran2007), Australia (e.g., Phillips, Reference Phillips2017), and Central and South America (e.g., Garcia-Ponce et al., Reference Garcia-Ponce, Mora-Pablo and Lengeling2021; Mackenzie, Reference Mackenzie2021), among others. The widespread and flagrant utilization of “nativeness” as a requirement in job advertisements appears both in the physical (e.g., Mahboob & Golden, Reference Mahboob and Golden2013; Selvi, Reference Selvi2010) and online worlds (e.g., Curran, Reference Curran2020, Reference Curran2021; Ruecker & Ives, Reference Ruecker and Ives2015). Such practices often position “native” speakers of English and ELT as a gendered, classed, and raced practice in the broader neoliberal restructuring of education that produces inequality and injustice for all ELT professionals (Block, Reference Block2017).

3. Discrimination based on speakerhood (i.e., [non-]nativeness) is not limited to recruitment policies and practices but also traverses into the workplace and manifests itself in various ways. These other forms of discrimination include, inter alia, widespread division of labor and legitimacy (NNESTs for receptive skills and NESTs for productive skills) (Choi & Lee, Reference Choi and Lee2016) and approaches to authenticity (Lowe & Pinner, Reference Lowe and Pinner2016), institutionalized dehumanizing impositions stripping teachers of their personal/professional identity by assigning them Anglicized names and forcing them to lie about their backgrounds (Tezgiden Cakcak, Reference Tezgiden Cakcak2019), microaggressions as institutionalized regimes of inequality and marginalization faced by ELT professionals of color (Lee & Jang, Reference Lee and Jang2022; Ramjattan, Reference Ramjattan2019c), and being subject to less payment, more teaching loads, and professional qualifications (Lengeling & Mora-Pablo, Reference Lengeling, Mora-Pablo, Roux, Vazquez and Guzman2012; Wong et al., Reference Wong, Lee, Gao, Copland, Garton and Mann2016).

4. Discrimination based on speakerhood is not the only axis characterizing the undemocratic and unethical employment landscape in the ELT profession. Recent studies adopted intersectional approaches in exploring practices, institutions, and policies, maintaining and exacerbating inequalities and hierarchies in the hiring practices and workplace settings. Some of these foci and nexuses include race (and raciolinguistics) (e.g., Daniels & Varghese, Reference Daniels and Varghese2020; Flores & Rosa, Reference Flores and Rosa2015; Jenks, Reference Jenks2017; Ramjattan, Reference Ramjattan2019a, Reference Ramjattan2022; Rivers & Ross, Reference Rivers and Ross2013), accent (Matsuda, Reference Matsuda2012), gender (e.g., Appleby, Reference Appleby2013; Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi2014; Park, Reference Park2015), and ethnicity (e.g., Kubota & Fujimoto, Reference Kubota, Fujimoto, Houghton and Rivers2013). Collectively, we adopt a more complex and multifaceted approach to understanding discrimination as a multifaceted construct based on many dimensions, including skin color, ethnicity, nationality, gender, age, religion, disability, sexual orientation, and other physical attributes – both individually or in some combination, and in a context-dependent manner (e.g., Whiteness [or lack thereof] may be an index of professional qualification and legitimacy in various contexts).

5. Drawing upon poststructuralist theory and moving beyond the earlier intersectional accounts, an emergent body of literature, emanating predominantly from Japan, challenges the uniformity of experiences pertinent to privilege, marginalization, and discrimination in ELT (e.g., Appleby, Reference Appleby2016; Houghton & Rivers, Reference Houghton and Rivers2013; Jenks, Reference Jenks2017; Kubota & McKay, Reference Kubota and McKay2009; Lowe, Reference Lowe2020; Rudolph, Reference Rudolph2019; Rudolph et al., Reference Rudolph, Selvi and Yazan2015). Documenting privilege enjoyed by and discrimination and discriminatory practices against NESTs (Lowe, Reference Lowe2020), the literature provides a forceful critique that calls for reconceptualizing native speakerism as a contemporary social problem rather than an ideological construct (Houghton & Rivers, Reference Houghton and Rivers2013) in a contextually sensitive manner conducive to individuals’ sociohistorical negotiations of being and becoming (Rudolph et al., Reference Rudolph, Selvi and Yazan2015). The most significant contribution of this line of research is twofold: first, documenting the fluid constructions of privilege-marginalization within and across “categories” of being in and beyond the classroom (Rudolph, Reference Rudolph2016) and, second, broadening the conceptual scope of criticality beyond juxtaposed binaries of NESTs and NNESTs. Collectively, the new research prioritizes (in)equity, privilege, marginalization, and discrimination by moving away from the universalized/essentialized links between binaries of identity and lived experiences (i.e., “NESTs are privileged and NNESTs are marginalized”) to a dynamic position (i.e., “All ELT professionals may potentially experience privilege and marginalization in relation to their perceived/ascribed identities in a given context”) (Yazan & Rudolph, Reference Yazan and Rudolph2018).

These theoretical discussions and practical explorations broaden, complexify, and diversify the multifaceted nature of discrimination in ELT. In this picture, the nomenclature debate (enacting various ideological positions through strategic lexical manipulations) will continue to serve as an ideological fault line for the ELT professionals. Therefore, there have been calls for taking a broader approach to understanding how markets influence our ways of knowing the world (Block, Reference Block2017), entangled with the local complexities of language, power, struggle, history, and dominance (Pennycook, Reference Pennycook2020).

4.7 Methodological developments, approaches, tools, and explorations

The methodological developments in the NNEST research literature follow the conceptual push to: (a) go beyond the binary and universal categorization of language teachers as NEST and NNEST and (b) explore the complexity in the experiences and identities of English language practitioners in their professional life. Moussu and Llurda's (Reference Moussu and Llurda2008) review includes the following methods in the early decade of research on NNESTs: “non-empirical reflections on the nature and conditions of NNS teachers, personal experiences and narratives, surveys, interviews, and classroom observations” (p. 132). In the current review, we approach researchers’ methodological choices in two dimensions: methodological genre (e.g., case study) if articulated and the methods used to gather data. We made five main observations that we will discuss below. First, scholars have used qualitative research methods the most with a specific emphasis on the methods within the traditions of ethnography and case study, while there are still recent quantitative-oriented studies. Second, an increasing number of scholars have relied on the affordances of mixed-methods approaches by combining quantitative and qualitative data (mostly explanatory design). Third, following Pavlenko's (Reference Pavlenko2003) seminal work, more scholars have analyzed teacher education classroom data collected through the implementation of innovative teacher learning activities that include the questioning of language ideologies (including ideologies of “nativeness”). Fourth, researchers experimented with the use of new qualitative data sources (e.g., arts-based techniques) and combined analyses of multiple data sources (e.g., policy documents and interviews). Fifth, there has been an increase in the use of autoethnographic methods, which scholars individually or collectively used to analyze the relationship between themselves, others, and discourses.

First, the studies that have been published since the last review (Moussu & Llurda, Reference Moussu and Llurda2008) used qualitative methods predominantly. Most of those studies do not specify a methodological genre in their research design. They tend to describe how they have followed the qualitative methods of data collection (typically interviews and observations) and analysis in general (e.g., Aneja, Reference Aneja2016a; Ateş & Eslami, Reference Ateş and Eslami2012; Brown & Ruiz, Reference Brown and Ruiz2016; Doan, Reference Doan2016; Galloway, Reference Galloway2014; Park, Reference Park2012). Some of those qualitative studies solely used interview data (Atay & Ece, Reference Atay and Ece2009; Copland et al., Reference Copland, Mann and Garton2020; Huang, Reference Huang2019; Leonard, Reference Leonard2019; Song, Reference Song2016b), while others drew from multiple data sources. For example, Galloway (Reference Galloway2014) analyzed teachers’ interviews, diaries, and focus groups without following a specific methodological genre of qualitative research to examine a multilingual NNEST's experience with her “fake American” accent in Japan. The studies that follow a specific methodological genre of qualitative research usually choose case study (e.g., Faez & Karas, Reference Faez and Karas2019), ethnography (e.g., Appleby, Reference Appleby2016), or narrative inquiry (e.g., Fan & de Jong, Reference Fan and de Jong2020; Rudolph et al., Reference Rudolph, Yazan and Rudolph2019) and sometimes combine the affordances of different genres eclectically (Burri, Reference Burri2018; Menard-Warwick et al., Reference Menard-Warwick, Bybee, Degollado, Jin, Kehoe and Masters2019; Yan, Reference Yan2021; Zheng, Reference Zheng2017). For example, Menard-Warwick et al. (Reference Menard-Warwick, Bybee, Degollado, Jin, Kehoe and Masters2019) utilized an ethnographic case study to examine how English language teachers “appropriate historically-available discourses about English and ELT for their own identity development” in urban Guatemala, rural Nicaragua, and a Tibetan refugee community in India (p. 367). Moreover, another line of qualitative research uses content analysis or (multimodal) critical discourse analysis in the studies that examine job advertisements and recruitment documents (e.g., Ahn, Reference Ahn2019; Alshammari, Reference Alshammari2021; Daoud & Kasztalska, Reference Daoud and Kasztalska2022; Lengeling & Mora-Pablo, Reference Lengeling, Mora-Pablo, Roux, Vazquez and Guzman2012; Mahboob & Golden, Reference Mahboob and Golden2013; Rivers, Reference Rivers, Copland, Garton and Mann2016; Ruecker & Ives, Reference Ruecker and Ives2015; Selvi, Reference Selvi2010). In addition to the exponential increase in qualitative studies, researchers used quantitative research methods (mostly via questionnaires) to reach out to broader populations of participants who are teachers, students, parents, and school administrators (e.g., Aslan & Thompson, Reference Aslan and Thompson2017; Azian et al., Reference Azian, Raof, Ismail and Hamzah2013; Buckingham, Reference Buckingham2014; Clark & Paran, Reference Clark and Paran2007; Moussu, Reference Moussu2010; Shibata, Reference Shibata2010). For example, Aslan and Thompson (Reference Aslan and Thompson2017) used “a semantic differential assessment scale that consisted of adjective pairs (e.g., approachable vs. unapproachable)” to understand “learners’ situated perceptions about teachers of English as a second language (ESL) in the classroom” (p. 277).