The skeletons of 12 people, including adults, children and adolescents, were found in a pit at Uğurlu, on the island of Gökçeada, Turkey. The bodies were thrown into the pit and covered by large stones. Such burial pits are unique in Anatolian and Aegean prehistory, the only exception being the death pit at Domuztepe (Kansa et al. Reference Kansa, Gauld, Campbell and Carter2009). The island of Gökçeada (Imbros) is about 17km from the Gelibolu Peninsula in the North-eastern Aegean (Figure 1). Stratigraphic excavations at Uğurlu have clarified the spatial extent of the settlement from the initial Neolithic occupation onwards (6800 cal BC), and brought to light evidence of a 5500 cal BC transition to a communal building, which is marked by major changes in pottery production, subsistence economy, settlement organisation and building plans (Erdoğu Reference Erdoğu2014, Reference Erdoğu2017). This transitional period also saw the creation of 30 pits surrounding the communal building in the western part of the settlement.

Figure 1. Location of Uğurlu in the North-eastern Aegean.

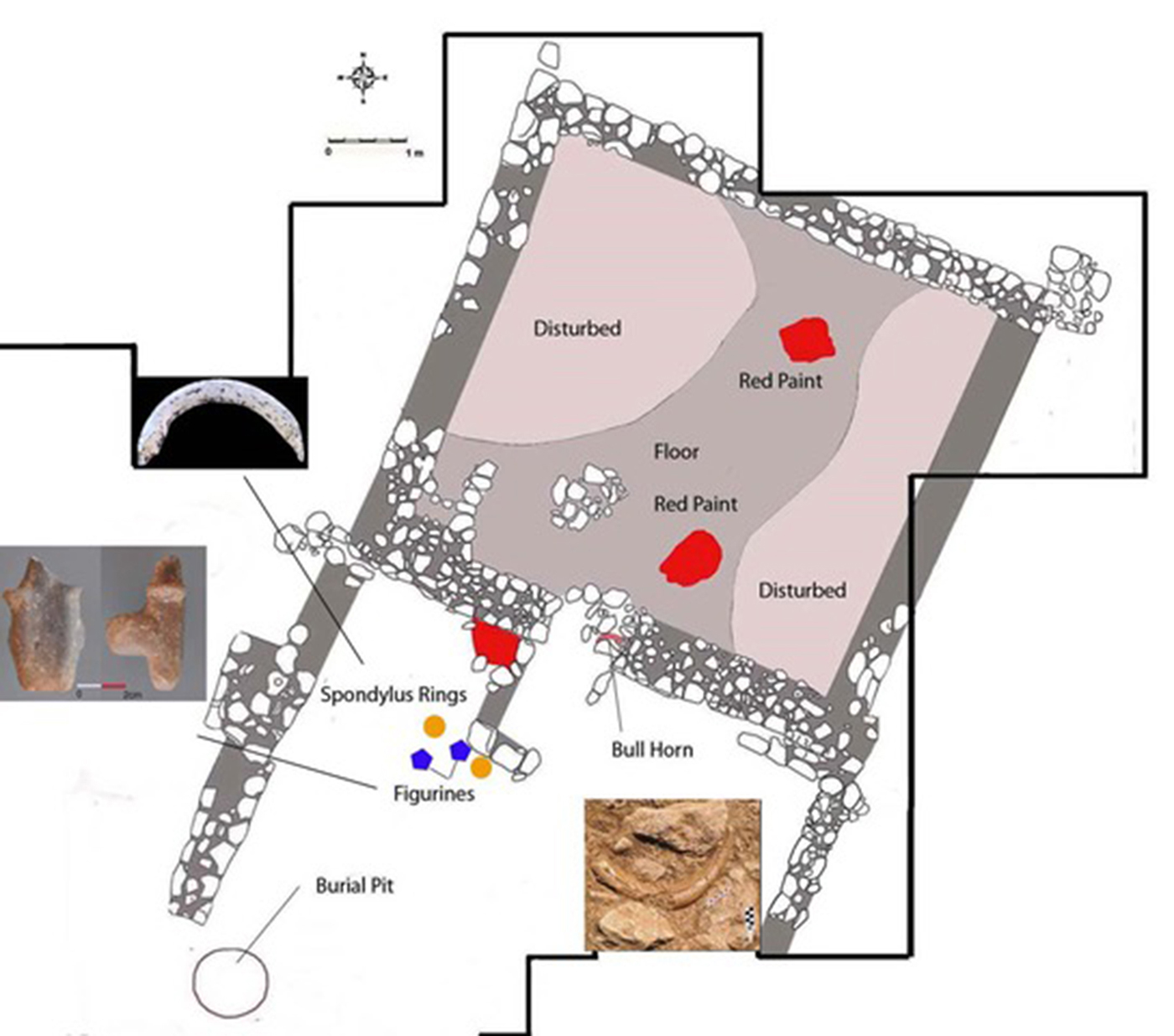

The communal building is rectangular in plan, measures approximately 7m wide × 7m long, and is constructed with stone walls (Figure 2). The building was poorly preserved and damaged by surface activities. A large bull's horn was found on the threshold of the building. The floor of the building was plastered with burnt lime mixed with soil and sediment. Traces of red paint remain on parts of the floor's surface, including near the entrance. Building decorations with animal horns and paintings on walls and floors appear as early as the Pre-Pottery Neolithic A in the Near East, and are often related to communal or public buildings (Verhoeven Reference Verhoeven2002). No finds were discovered on the floor. On the other hand, some significant finds, such as two clay figurines and Spondylus bracelets, were found just outside of the building, close to the entrance.

Figure 2. Plan of the communal building and the location of the burial pit (figure credit: Uğurlu Archive).

Around the communal building, 30 pits were excavated. The inner walls and bottoms of the pits were plastered with yellow-coloured clay, between 30 and 50mm thick. The pits were circular in shape, some as deep and wide as 1m. Pits were deliberately infilled with large stones and fragments of pottery and animal bones. Among the pottery, ‘eared pots’ reminiscent of human skulls were significant. Within the pits were bracelets or rings made from Spondylus gaederopys, pendants of Cerastoderma, bone and flint tools, stone axes and clay and marble figurines (Karamurat Reference Karamurat2018).

The burial pit was found in the courtyard of the communal building. It measures approximately 1 × 1.2m across and about 1.5m in depth. Although the excavation of the pit is not yet complete (at least two individuals are still in the ground), 10 skeletons have been lifted and studied in detail using the technique developed by Buikstra and Ubaleker (Reference Buıkstra and Ubaleker1994) (Figures 3–6). All age groups and both sexes are represented, including a three-year-old child and adult males and females (Table 1). Two AMS dates from the stratigraphically highest and lowest skeletons so far removed yield a result around 5300 cal BC (Table 2). These remains were concurrent with the communal building. All skeletons, except one (skeleton 6), were fully articulated. The positions of the skeletons suggest that they were thrown into the pit rather than carefully placed. The juxtapositions of the extremities of different individuals and the chronology of depositions suggest that bodies were thrown into the pit one by one, probably simultaneously or within a short period of time that did not allow for the earlier skeletons to decompose. Small and large stones, around 100g to 80kg in weight, were thrown in after each body. Skeletons were heavily damaged by stones, and display breaks to fresh bone as well as dry bone. No pathological lesions were observed on the bones; trauma-related breaks would be difficult to recognise, however, due to the bone breaks caused by heavy rocks immediately post-mortem. One skeleton belonged to a 10–12-year-old child (skeleton 6) whose lower body was disturbed, probably during decomposition by the weight of other skeletons and large stones. Some skeletal parts of other individuals show slight displacements from their anatomical positions due to gravity, which suggests that there were voids within the burial pit, which allowed for collapse.

Figure 3. Adults and adolescents from the top layer of the burial pit; metric scale: 10cm (photograph credit: Uğurlu Archive).

Figure 4. Intertwined burials and large stones; metric scale: 10cm (photograph credit: Uğurlu Archive).

Figure 5. An adult female among large stones; metric scale: 10cm (photograph credit: Uğurlu Archive).

Figure 6. An adult female and animal bones at the lower layer of the burial pit; metric scale: 10cm (photograph credit: Uğurlu Archive).

Table 1. Age and sex distribution of individuals from grave pit 88.

* Skeleton numbers represent stratigraphical order, e.g. skeleton 1 is the highest one in the burial pit. Overall age categories: infant) 0–3; juvenile) 3–12; adolescent) 12–20; young adult) 20–30; mature adult) 30–40s; old adult) approximately 50+.

Table 2. Conventional and calibrated radiocarbon dates from the Uğurlu communal building and burial pit.

Some fragmented and disarticulated animal bones were found distributed throughout the pit. At the bottom of the pit, articulated forearm and leg bones of two young cattle were also found. Neither cut marks nor burning were detected on the bones; these partially articulated extremities must therefore have been thrown in still fleshed. The remains of young cattle might have been part of ritual offerings. Excavation of this burial pit continues, and it is not yet clear whether the remains of the 12 individuals were part of local burial customs or ceremonial sacrifices.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Jarrad W. Paul for his kind corrections to the language, and Cem Öztürk for his comments on animal bones. Uğurlu projects are supported by the Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism. We also wish to thank the Turkish Science Foundation (TÜBİTAK project no: 114K271) for radiocarbon dates.