Introduction

Issuers seeking to go public may take many factors into consideration when choosing listing venues that best suit their private needs, such as the geographical link of their businesses with a particular market, the market valuation at the initial public offering (IPO) stage, and the regulatory space for founders to maintain control.Footnote 1 Financial globalisation has given issuers more freedom to carry out jurisdiction shopping and has thus intensified stock market competition. Against this backdrop, the dual-class share structure (DCSS) has obtained growing acceptance in the global listing community over recent years, such as in Hong Kong (2018),Footnote 2 Singapore (2018),Footnote 3 and China (2019).Footnote 4 Also, the UK authority has recently removed the DCSS taboo on the London Stock Exchange (LSE) Premium Main Market to sharpen its competitive edge in the post-Brexit era.Footnote 5

The DCSS is not novel in the global listing community, which has historically experienced varied positions in many jurisdictions. Whilst empirical legal studies examining the impact of voting mechanism alteration, ie conversion from one-share-one-vote (OSOV) to DCSS or the other way round, on corporate value change on a jurisdiction-specific basis have generated an enormous body of literature,Footnote 6 the impact of the DCSS on inter-jurisdictional market competition is rarely explored empirically. Has the supply-front reform of introducing the DCSS helped the involved stock markets attract issuers to reshape the landscape of market competition? If so, to what extent? If not, what are the reasons?

The research gap arises probably from the difficulty in finding suitable jurisdictions, in which policy differences and changes concerning the DCSS may serve as a determinant of inter-jurisdictional market competition. Also, cross-country data collection may have presented considerable challenges. Attempting to narrow the research gap, this paper, based on hand-collected data, seeks insights by examining the efficacy of the DCSS in helping the Chinese and Hong Kong stock markets attract Chinese issuers, compared to that in the US. The US, China and Hong Kong stand out as good choices for such an empirical study because they have global financial centres with five of the top ten stock exchanges, which compete with each other for Chinese issuers.Footnote 7 Moreover, both China and Hong Kong have recently removed the long-standing DCSS taboo to respond to competitive pressure from the US, and thus the policy changes have provided a context for detecting the impact of the DCSS on inter-jurisdictional market competition.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Section 1 discusses the reasons for the removal of the DCSS taboo in the Chinese and Hong Kong stock markets. Certain concerns are drawn from both a theoretical analysis of the DCSS's benefits for market development and an empirical study of US-listed Chinese DCSS issuers covering two decades (2000–2019) to reflect competitive pressure as a driver of the Chinese and Hong Kong policy changes. Section 2 explores the landscape of listings with a DCSS in the Chinese and Hong Kong stock markets in the post-reform era and finds the infrequent dual-class listings. Sections 3 and 4 propose and test two hypotheses, ie low demand and limited allowance, to explain the infrequent dual-class listings in China and Hong Kong. Section 5 considers policy implications for both the involved jurisdictions and beyond. The paper ends with concluding remarks.

1. The introduction of the dual-class share structure in China and Hong Kong to attract Chinese issuers

On 30 April 2018, Hong Kong enacted new listing rules to revisit the DCSS in its stock market.Footnote 8 This was followed by the establishment of the Shanghai Stock Exchange Sci-tech Innovation Board (SSE STAR Board) on 13 June 2019 with the introduction of the DCSSFootnote 9 and then the removal of the DCSS taboo on the Shenzhen Stock Exchange ChiNext Board (SZSE ChiNext Board) on 12 June 2020.Footnote 10 This section deciphers the aforesaid Chinese and Hong Kong stock market reforms from both theoretical and empirical perspectives.

(a) The benefits of the DCSS

Equity ownership generally represents an entitlement to residual cash flows and votes.Footnote 11 In many jurisdictions, publicly traded companies must ensure that all shares carry one vote per share, thereby granting shareholders the same proportion of voting rights provided they hold the same amount of shares. This is generally known as the proportionality concept or the OSOV principle.Footnote 12 Through aligning voting power with cash-flow rights, the OSOV principle allows shareholders to voice their viewpoints proportionally to their equity ownershipFootnote 13 so as to ensure shareholder democracy and then to encourage investment.Footnote 14 In contrast, DCSS companies issue different classes of shares with disparate voting power.Footnote 15 Through holding superior voting shares, corporate founders can thus become controlling shareholders with disproportionate equity ownership.Footnote 16

Issuers seeking to go public may have had several rounds of equity financing that have largely diluted founders’ shareholding.Footnote 17 Consequently, out of the concern for losing control, founders may be reluctant to float their companies unless they are granted safeguards to maintain managerial autonomy.Footnote 18 Owing to its function of combining the advantages of public fundraising in the stock market with the maintenance of corporate control, the DCSS is attractive to founders.Footnote 19 Accordingly, from the standpoint of stock markets, as founders often have a decisive say on choosing the listing venue, permitting the DCSS can enhance their attractiveness to prospective issuers.Footnote 20

Besides, the DCSS can counteract market short-termism to foster entrepreneurship. Investors may have an economic incentive to get immediate investment returnsFootnote 21 and pursue takeover premiums with disruptive changes to incumbent management,Footnote 22 as observed by empirical research that a diminishingly shortened period of shareholding is emerging for short-term returns.Footnote 23 Given this, permitting founders to maintain control to a certain degree can utilise their idiosyncratic visions for corporate long-term value creation without paying attention to temporary stock price fluctuation and hostile takeover challenge.Footnote 24 This is particularly meaningful to many Chinese technology sector companies, which had a relatively short operating history and negative net profits at the time of listing.Footnote 25

Financial globalisation has enabled issuers to conduct jurisdictional arbitrage. As such, the benefits of the DCSS in boosting market development account for their ever-expanding acceptance in the global listing community. Also, China and Hong Kong have removed the DCSS taboo to make their bourses more capable of competing with their US counterparts. The following subsection employs an empirical perspective to understand inter-jurisdictional market competition as a driver of the Chinese and Hong Kong policy changes.

(b) Competitive pressure as a driver: an empirical analysis of Chinese companies’ US listings

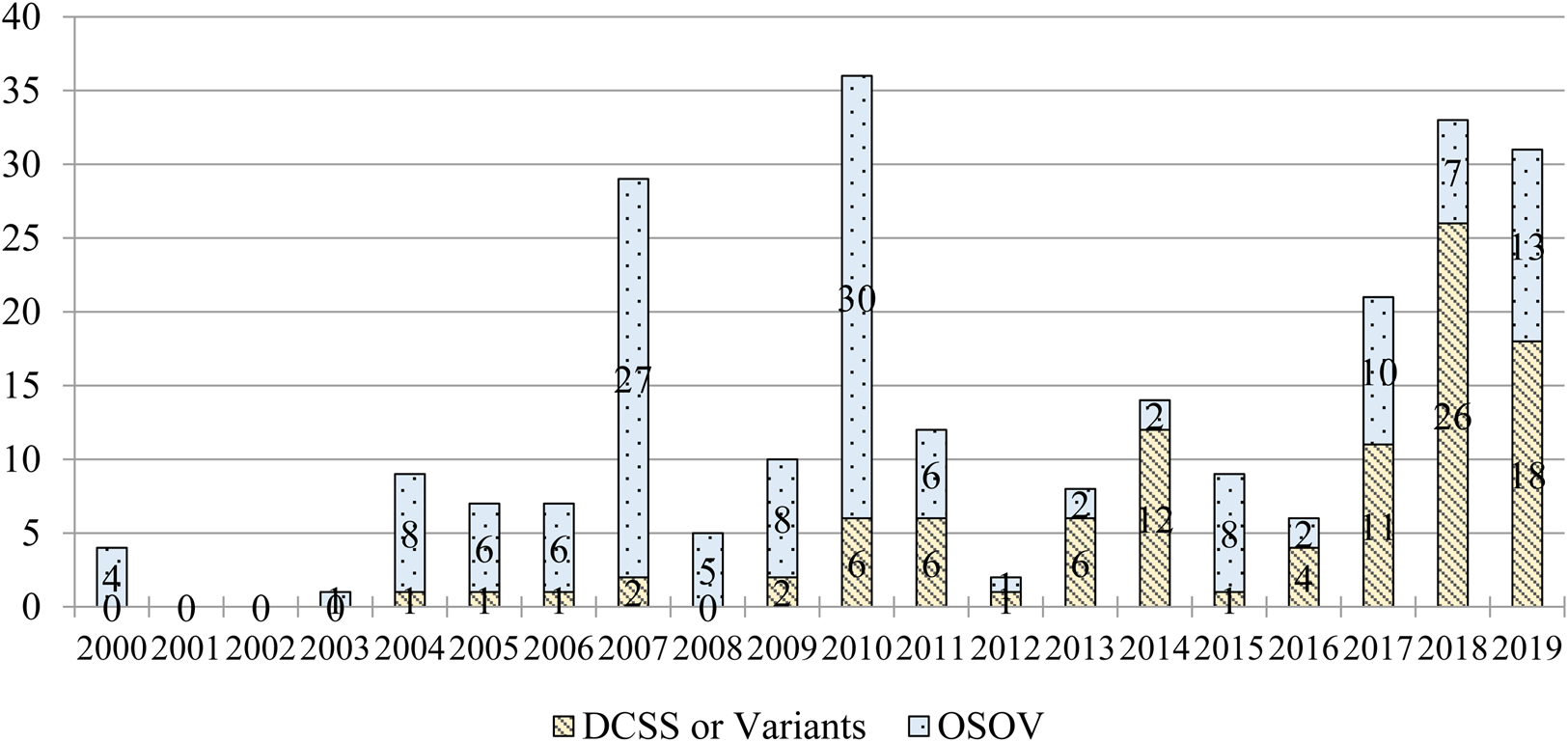

Chinese companies’ US listings commenced in 1992 when China Brilliance Automotive Inc went public on the NYSE.Footnote 26 Thereafter, hundreds of Chinese issuers floated in the US. From 2000 to 2019, 244 Chinese issuers were listed on either the NYSE or NASDAQ; of these, 98 adopted a DCSS or variant, accounting for 40.2% of the total US-listed Chinese issuers in number (see Figure 1). Moreover, three companies (stock symbols: NETS, SOHU and SINA) have witnessed the US listing of their spin-offs (stock symbols: DAO, SOGO and WB respectively), all of which have issued dual-class shares.

Figure 1. The use of a DCSS or variant by US-listed Chinese companies in 2000–2019

Figure drawn by the author. Data as of 31 December 2019. Data are collected from the NYSE, NASDAQ and SEC. Companies that have gone public via a reverse acquisition are excluded. Chinese SOEs, dual-listed companies and blank check companies are excluded. Delisted companies are counted. Companies that have converted their voting mechanisms from the OSOV to DCSS or the other way round are classified according to their initial voting arrangements.

To make further comparisons between the US-listed Chinese DCSS issuers and their OSOV counterparts, this paper excludes six companies (stock symbols: SINA, CCM, NOAH, VIPS, HEBT and ATHM) because they have converted their voting mechanisms from the OSOV to DCSS or the other way round. As such, the comparison subjects are 97 US-listed Chinese DCSS issuers and their 141 OSOV counterparts. Some empirical findings are as follows.

As at 31 December 2019, 18 out of the 97 DCSS issuers (18.6%) were delisted, compared to 79 delisted companies out of the 141 OSOV counterparts (56.0%). As for the 79 DCSS companies and 62 OSOV companies that remained quoted, the total market capitalisation of the former was US$898.9 billion, while the latter was US$117.6 billion (see Table 1). Thus, the lower delisting rate and much larger market capitalisation can reflect the financial dominance of DCSS issuers in the landscape of Chinese companies’ US listings, compared to their OSOV counterparts.

Table 1. Comparison between US-listed Chinese DCSS and OSOV companies

Note: Table drawn by the author. Data as of 31 December 2019. Data are collected from the NASDAQ and YCharts Database.

Moreover, the total market capitalisation of the 79 US-listed Chinese companies with a DCSS or variant (US$898.9 billion) equated to 10.6% of the combined market capitalisation of all the 3,584 companies listed in the Chinese stock market or 18.4% of the combined market capitalisation of all the HKEX-listed companies at the end of 2019.Footnote 27 Perhaps more noteworthy is the manner in which the US-listed Chinese business giants dominate the technology scene, consistently developing technologies, boosting innovations and expanding business territories. This is the background against which moves by Chinese and Hong Kong policymakers to introduce the DCSS to enhance the attractiveness of their global financial centres to Chinese issuers are to be considered.

2. The use of the dual-class share structure in the post-reform Chinese and Hong Kong stock markets

Given that over 40% of Chinese companies listed in the US used a DCSS or variant in 2000–2019, market expectations would be that the Chinese and Hong Kong stock market reforms of introducing the DCSS on the supply side would have attracted many Chinese companies to go public in China or Hong Kong with the issuance of dual-class shares. However, the market practice has shown a different picture.

At the end of 2021, 371 Chinese companies were quoted on the SSE STAR Board with only four of them acting as DCSS issuers.Footnote 28 In parallel, from the removal of the DCSS taboo on the SZSE ChiNext Board on 12 June 2020 to 31 December 2021, 279 Chinese issuers floated on the SZSE ChiNext Board with the use of a DCSS by none of them. As for the landscape of Hong Kong, from 30 April 2018 to 31 December 2021, 322 Chinese companies went public on the HKEX Main Board; of these, only six used a DCSS.Footnote 29

The fact that DCSS use is not popular in the Chinese and Hong Kong stock markets is more striking when compared to the continued prevalence of Chinese issuers’ US dual-class listings in the same period. From 13 June 2019 to 31 December 2021, 82 Chinese companies went public in the US with the adoption of a DCSS by 47 of them, while from 30 April 2018 to the end of 2021, 120 Chinese companies floated in the US with the use of a DCSS by 74 of them (see Table 2).

Table 2. Comparison of listings with a DCSS in China, the US and Hong Kong

Table drawn by the author. Data are collected from the HKEX, SSE, SZSE, NYSE and NASDAQ. Companies that have transferred from the Hong Kong Growth Enterprise Market to the HKEX Main Board are excluded. Dual-listed companies are excluded.

The US practice has revealed the competitive advantage of admitting the DCSS in accommodating Chinese issuers, whereas the infrequent dual-class listings in China and Hong Kong in the post-reform era indicate that the benefits of the DCSS in enhancing stock market attractiveness are merely a myth. The diametrical efficacy of the DCSS seems perplexing. The following sections propose and verify two hypotheses, ie low demand and limited allowance, to explain the unpopularity of listing with a DCSS in the Chinese and Hong Kong stock markets in the post-reform epoch.

3. The low demand hypothesis, methodology and evidence

In light of the cost-benefit analysis, when making a decision, a rational person compares the potential costs and benefits associated with the project decision to determine whether it makes sense.Footnote 30 This means that for it to be legally possible to adopt a DCSS is only the starting point – if founders are actually to exercise this option, the benefits of doing so must exceed the costs. For founders, generally, the benefits of conducting a dual-class listing lie in two aspects, ie the private benefits of control and listing premiums. If the two aspects are incompatible, rational persons would make a trade-off to maximise their interests, as revealed by scholarly studies that some companies have ceased DCSS usage in exchange for investment opportunities and value enhancement.Footnote 31

Given that the DCSS was newly introduced in the Chinese and Hong Kong stock markets, it is not surprising that investors may fear the potential risks of buying into dual-class companies, and the market fear may impinge negatively on the market valuation of a dual-class listing. Therefore, if substitutes are available, DCSS usage may not be in high demand. Instead, rational issuers are likely to give more weight to higher share price and employ the proportionality doctrine to signify good corporate governance to the stock market pricing mechanism.Footnote 32 Put differently, the low viability of the DCSS in the Chinese and Hong Kong stock markets may be attributed to the use of substitutive instruments.

To test the low demand hypothesis, this paper first examines the availability of substitutive control-enhancing instruments under the Chinese and Hong Kong legal frameworks and then investigates whether and the extent to which the use of substitutes may have accounted for the unpopularity of DCSS usage. To enrich comparative legal analyses, some facets of securities regulation and market practice in the Anglo-American stock markets will also be discussed, while relevant implications will be considered later in Section 5.

(a) The use of PSSs and SVAs as substitutes for the DCSS in China and Hong Kong: a theoretical perspective

Under the Chinese and Hong Kong regulatory frameworks, substitutive control-enhancing instruments typically include the pyramid shareholding structure (PSS) and shareholder voting agreement (SVA).

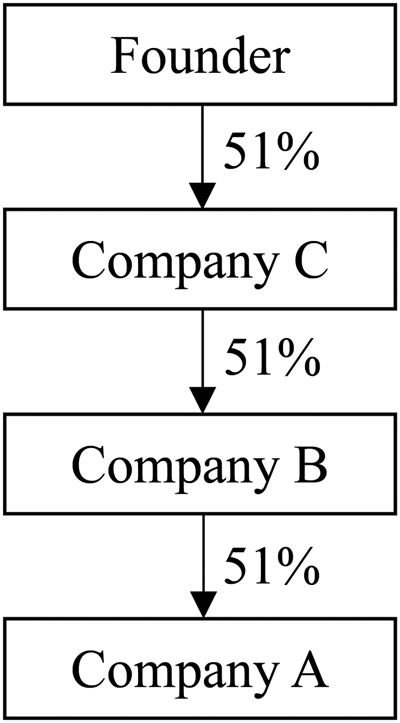

A PSS employs a multi-firm hierarchy to leverage founder control, in which a high-tier company holds a large portion of the shares of a low-tier company, which in turn holds the shares of a lower-tier company, and as such, the major shareholder of the high-tier company can have a disproportionate say on the corporate affairs of companies at low tiers.Footnote 33 As illustrated in Figure 2 below, assuming the adoption of the OSOV principle and that the founder holds 51% of the equity stake in Company C, which itself owns 51% of the shares in Company B, which in turn owns 51% of Company A, through the corporate chain, the founder has 51% of the voting power in Company B by holding 26% of the equity ownership (51% * 51%). The divergence between cash-flow and voting rights can be further amplified at the bottom tier,Footnote 34 as shown that Company A is 51% controlled by the founder who holds only 13% of the equity stake (51% * 51% * 51%).

Figure 2. An illustrative example of the PSS

Figure drawn by the author.

The PSS enables the founder to divest his equity stake in Company A while not losing control. For this to be effective, the critical condition is that the founder has the majority voting rights but not entire equity interests in companies at each tier of the PSS.Footnote 35 Apart from that, the creation of a PSS may be subject to other limits, depending on how the PSS is constructed. Generally speaking, the founder could establish a PSS before or after the listing of the operating entity in either an upwards or downwards manner.

If the PSS is constructed upwards prior to IPO, the founder will need to introduce intermediate companies between himself and Company A and attract investment into the intermediate companies.Footnote 36 In detail, the founder may take the following steps: (i) incorporate Company B as his wholly-owned corporate entity; (ii) transfer his 51% of the equity stake in Company A to Company B; (iii) sell 49% of Company B to unaffiliated investors; (iv) incorporate Company C as his wholly-owned corporate entity; (v) transfer his 51% of the equity stake in Company B to Company C; (vi) sell 49% of Company C to unaffiliated investors; (vii) list Company A. In this way, the founder can dilute his ownership in Company A from 51% to 13% while not losing control. However, the effectiveness of such corporate restructuring and equity financing processes would depend on whether the founder could manage to introduce unaffiliated investors. As shown in Figure 2, the more the tiers are inserted in the PSS, the greater the separation of the founder's equity stake and voting rights in Company A. Accordingly, the decreased equity stake may amplify the founder's incentive to extract private benefits of control.Footnote 37 Consequently, potential investors may regard the creation of intermediate companies as a sign that the founder aims to conduct control extractionFootnote 38 and may vote with their feet to buy into other companies.

If a PSS is constructed downwards before IPO, the founder may take steps as follows: (i) incorporate Company B as a wholly-owned subsidiary of Company A; (ii) transfer Company A's business to Company B; (iii) sell 49% of Company B to unaffiliated investors; (iv) incorporate Company C as a wholly-owned subsidiary of Company B; (v) transfer Company B's business to Company C; (vi) sell 49% of Company C at IPO; (vii) list Company C. Whilst such a PSS can leverage founder control, it may encounter resistance from involved investors. In many jurisdictions, such as the UK, IPOs represent an effective exit route for investors who often sell out their stakes in the investee company shortly after IPO.Footnote 39 Thus, if Company A were to be listed, the initial investors of Company A could exit completely for investment returns. In contrast, upon the creation of the PSS, the business would be transferred from Company A to Company C with the latter to serve as the listed entity. As a result, the initial investors of Company A could only sell a proportion of their equity stake in Company C at the IPO stage, ie 12.25% at most (49% * 51% * 49%).Footnote 40 For this reason, forming a PSS downwards may be resisted by Company A's initial investors at the beginning.

Alternatively, a PSS could be established upwards or downwards post IPO. However, forming a PSS upwards post IPO may raise a mandatory offer issue, besides the difficulties in attracting unaffiliated investors into the intermediate companies.Footnote 41 In detail, if Company B and Company C were to be introduced after the listing of Company A, Company B would need to acquire the founder's 51% of the equity stake in Company A. In China, Hong Kong and many other jurisdictions including the UK, an acquirer (and persons acting in concert with him, if there are any) who has acquired 30% or more of the shares of a listed company is required to make a mandatory offer to all other shareholders of the company.Footnote 42 Thus, the founder should be cautious about triggering mandatory offer requirements. The founder could, instead, attempt to form a PSS downwards post IPO. However, transferring the listed operating entity's business to a new company initially controlled by the founder and afterwards listing the transferee may, in many jurisdictions, constitute a related-party transaction and require minority shareholder approval.Footnote 43 On these grounds, forming a PSS post IPO is not easy either, regardless of whether it is conducted upwards or downwards.

Besides the PSS, the SVA is another instrument that can leverage founder control. An SVA is a voluntary contract governing the relationship of signatory shareholders,Footnote 44 whereby involved shareholders agree to vote as a single block to exert considerable influence on corporate affairs, such as the election of board members.Footnote 45 Take Yunyong Electronics and Technology Co Ltd (stock symbol: 688021), a STAR-listed company, for example: Yunyong's largest two shareholders – who hold 33.75% and 22.5% of the total shares – have entered into an SVA, thereby becoming co-controlling shareholders with 56.25% of the total voting power.Footnote 46

The functions and effects of SVAs can be replicated by persons acting in concert of their own accord, nevertheless with an extra proof of voting coalition.Footnote 47 If any shareholder who is a party to the SVA were to exercise his voting power in a manner contrary to the SVA, other signatory shareholders would have a locus standi to initiate a contractual claim against the non-complying shareholder.Footnote 48

The use of an SVA to leverage founder control is not uncommon amongst private companies. In the listed company sphere, however, whether an SVA is workable or not depends considerably on the ownership structure of the involved company. In China and Hong Kong, where the stock markets are dominated by publicly traded companies with block holders, it is relatively easy for the founder to conclude an SVA with a few block holders to become co-controlling shareholders, as revealed by the Yunyong case. In contrast, in jurisdictions in which listed companies usually have a highly dispersed ownership, eg the US and the UK, SVAs may not act as effective substitutes for the DCSS because it is fairly difficult, if not impractical, for the founder to enter into an SVA with a multitude of minority shareholders to achieve collective control.Footnote 49

In fact, the founder's ownership of the operating entity also determines how difficult it is to set up a PSS. Figure 2 showcases a scenario in which the founder once owned 51% of the operating entity and then adopted a PSS to divest his ownership while maintaining control. In practice, the founder may have considerably diluted his ownership in the operating entity in pre-IPO equity financing (say, to 5%), but nevertheless aims to use a control-enhancing instrument to obtain no less than 51% of the voting rights after the listing of the operating entity. If so, the potential landscapes are as follows: (i) by using a PSS, the founder will need to incorporate at least four tiers between himself and the operating entity;Footnote 50 (ii) by using an SVA, the founder will have to collaborate with other shareholders who have at least 46% of the operating entity; (iii) by using a DCSS, the founder will need to set the weighted voting ratio between per superior voting share and per inferior voting share to be 20:1 or greater.Footnote 51 It seems that neither a PSS nor an SVA is as neat as DCSS usage to achieve founder control.

To make further comparisons, this paper examines the 10% of ownership and 20% of ownership scenarios. If the founder has 10% of the ownership in the operating entity and aims to obtain at least 51% of the voting rights, he will need to insert at least three tiers between himself and the operating entity in a PSS or conclude an SVA with other shareholders who own at least 41% of the operating entity or use a DCSS with a minimum weighted voting ratio of 10:1.Footnote 52 In the 20% of ownership situation, the corresponding conditions would be a PSS with at least two tiers between the founder and the operating entity or an SVA with other shareholders owning 31% or more of the operating entity or DCSS usage with a minimum weighted voting ratio of 5:1 (see Table 3).Footnote 53

Table 3. The comparison between the use of the PSS, the SVA, and the DCSS

Table drawn by the author.

Based on the discussion above, it could be seen that to maintain control over the operating entity, the less equity ownership the founder has, the more tiers he will need to insert in a PSS or the more shareholders he will have to collaborate with to reach an SVA, and vice versa. By comparison, the level of the founder's ownership in the operating entity only decides on the minimum weighted voting ratio in the use of a DCSS. The US listing rulebook does not set a cap on the weighted voting ratio in DCSS usage, while the newly revised UK listing regime requires the ratio not to exceed 20:1.Footnote 54 However, public shareholders may not understand or care about different weighted voting ratios. Thus, whilst DCSS usage with a weighted voting ratio of 5:1 or 20:1 may not cause substantial distinction in attracting investors, the founder's ownership of the operating entity determines the extent to which a PSS or an SVA could be used as an adequate substitute for the DCSS.

The equity ownership of many listed companies in the Anglo-American stock markets is highly dispersed, as opposed to its Chinese and Hong Kong counterparts. This accounts for the market preference for using the DCSS rather than the PSS or SVA to achieve founder control in the US listed landscape. Also, it means that even if the PSS and SVA may act as effective substitutes for the DCSS in China and Hong Kong, the availability of these control-enhancing instruments may not challenge the necessity of introducing the DCSS in the LSE Premium Main Market. Before casting light on policy implications for the UK and the wider community, the following subsection investigates the use of PSSs and SVAs in the Chinese and Hong Kong stock markets empirically.

(b) The use of PSSs and SVAs as substitutes for the DCSS in China and Hong Kong: an empirical study

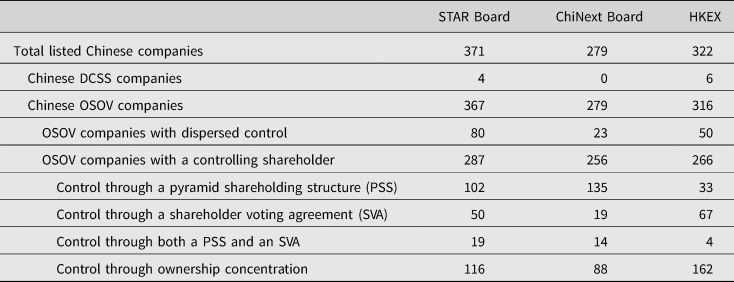

Based on an exhaustive examination of the prospectuses of the 962 Chinese OSOV companies listed on the SSE STAR Board, SZSE ChiNext Board and HKEX Main Board, this paper looks into their capital structure and control mechanisms and explores whether and the extent to which substitutes have been adopted to decrease the need for DCSS usage. Some noteworthy empirical findings are as follows.

First, the voting power concentration of the involved Chinese issuers was high. As of 31 December 2021, 367 and 279 Chinese OSOV issuers were listed on the SSE STAR Board and SZSE ChiNext Board respectively. Of these 646 Chinese OSOV issuers, only 103 had a dispersed control structure (including 80 STAR-listed companies and 23 ChiNext-listed companies), whilst the remaining 543 companies (84.1%, including 287 STAR-listed companies and 256 ChiNext-listed companies) had a controlling shareholder with no less than 30% of the total voting power.Footnote 55

Secondly, the use of a PSS and/or an SVA was prevalent. Amongst the 543 companies, the founders became controlling shareholders by adopting a PSS in 237 companies (including 102 STAR-listed companies and 135 ChiNext-listed companies), concluding an SVA in other 69 companies, and using both in other 33 companies. In addition, the founders of the remaining 204 companies (including 116 STAR-listed companies and 88 ChiNext-listed companies) achieved control by means of concentrated equity ownership,Footnote 56 either individually or with the support of persons acting in concert with them, which was based on consanguinity or affinity rather than contractual ties.

The empirical study regarding the Chinese OSOV issuers listed in Hong Kong from 30 April 2018 to 31 December 2021 produces similar findings. In this period, 316 Chinese OSOV companies went public on the HKEX Main Board; of these, 266 issuers (84.2%) had a controlling shareholder. Amongst the 266 issuers, 33 adopted a PSS, while other 67 counterparts employed an SVA to leverage founder control. Meanwhile, four companies used both a PSS and an SVA. In parallel, the founders of the remaining 162 companies achieved control by virtue of concentrated ownership (see Table 4).

Table 4. The control mechanisms of Chinese OSOV companies listed on the SSE STAR Board, SZSE ChiNext Board, and HKEX Main Board

Table drawn by the author. Data as of 31 December 2021. Data are collected from the SSE, SZSE and HKEX. The data of the SSE STAR Board, SZSE ChiNext Board and HKEX Main Board are counted from 13 June 2019, 12 June 2020 and 30 April 2018 respectively.

The empirical findings above reveal the existence of market needs to maintain founder control amongst a vast majority of Chinese issuers. However, owing to the availability of other control-enhancing instruments or ownership concentration as substitutes, a dual-class listing may be attractive but not essential. That is to say, the DCSS is not actually in high demand in the Chinese and Hong Kong stock markets, as might be anticipated.

4. The limited allowance hypothesis, methodology and evidence

The DCSS functions by decoupling the proportionality between voting power and equity stake to leverage founder control. This may nevertheless generate perils to public investors whose voting rights are adversely distorted. Generally speaking, the DCSS can impinge negatively on investor protection in two regards, ie management entrenchment and control extraction.

Where there is a controlling shareholder with a decisive say on director election and then manager employment, the management team would look to serve the interests of the controlling shareholder and be entrenched to public investors. As a result, not only would public investors be powerless to rectify managerial misconduct, but also the disciplinary function of takeovers in ensuring ‘the market for corporate control’ would become invalid.Footnote 57 Although similar problems may also occur in OSOV companies if block holders exist, evidently, the use of the DCSS is more likely to create a self-perpetuating oligarchy with entrenched management.

Also, the DCSS can aggravate the extraction of private interests, based on controlling shareholders’ decisive force in electing board members and passing resolutions at general meetings.Footnote 58 For example, controlling shareholders can pay their owner-director jobs excessive remuneration,Footnote 59 withdraw corporate funds,Footnote 60 tunnel corporate assets via related party transactions,Footnote 61 engage in empire building,Footnote 62 conduct buy-out at undervalue,Footnote 63 and pursue non-pecuniary benefits such as reputation and prestige.Footnote 64 The extraction may result in a downside of the share price that would damage the equity value of all shareholders, pro rata to their equity ownership. Therefore, extraction conducted by rational controlling shareholders is subject to a cost-benefit analysis by comparing the potential loss to the value of their equity stake with the expected gains of private interests.Footnote 65 In OSOV companies, control is achieved through crystallising a considerable amount of shares. The concentrated ownership can serve as a tie to bind controlling shareholders’ equity stake with the share price to mitigate the incidence of expropriation, ceteris paribus.Footnote 66 In contrast, DCSS usage enables certain shareholders to achieve control through a far smaller proportion of equity stake and, as such, the relatively low loss from the potential share value downside is more likely to incentivise controlling shareholders to extract private benefits.Footnote 67

Due to the perils of the DCSS, it is necessary to reinforce investor protection. Within the framework of the DCSS, the protection of investors and the attractiveness to issuers may represent competing interests. It means that adding weight to investor protection may reduce the market attractiveness to issuers, and vice versa. Investor protection can be achieved through employing ex ante regulatory measures to mitigate the incidence of opportunist behaviours, which may nevertheless make the involved stock market unattractive or even closed to issuers. Therefore, the low viability of the DCSS in China and Hong Kong may be attributed to the limited allowance caused by the restrictive ex ante regulatory measures in use.

To verify the limited allowance hypothesis, this paper first compares the differences between the US, China and Hong Kong in the ex ante regulation of DCSS usage and then investigates the extent to which the differences may have generated impact empirically.

(a) The disparity in ex ante regulation of DCSS usage

New Issuer Doctrine: The US stock market adopts a new issuer doctrine,Footnote 68 under which existing listed issuers are banned from converting their voting mechanism from OSOV to DCSS. Likewise, China and Hong Kong prohibit issuers that do not employ a DCSS at the IPO stage from distorting the voting proportionality thereafter.Footnote 69 The reasonableness lies in the fact that post-IPO investors buying into DCSS companies do not have a prior stake in the investee companies, and thus their rights are not reduced by a dual-class IPO. In contrast, if an existing listed company could, after flotation, create a new class of shares in favour of founders, the entitlement of other shareholders would be unfairly prejudiced.

Segmented Venue: DCSS usage is permitted in the whole NYSE and NASDAQ segments. By contrast, Chinese flotation with a DCSS is ringfenced to the SSE STAR Board and SZSE ChiNext Board, in which investors are required to have relatively sophisticated securities trading experience and high risk-bearing capacity.Footnote 70 As for the sell side, the controlling shareholder, actual controller and the largest shareholder of a DCSS issuer are bound to a lock-up period of 36 months, which is much longer than counterpart OSOV listings (ie 12 months).Footnote 71 As such, by restricting the usage scope to segmented boards with relatively sophisticated investors and a prolonged lock-up period for issuers, it is expected to mitigate the potential negative impact of introducing the DCSS on the whole Chinese stock market.

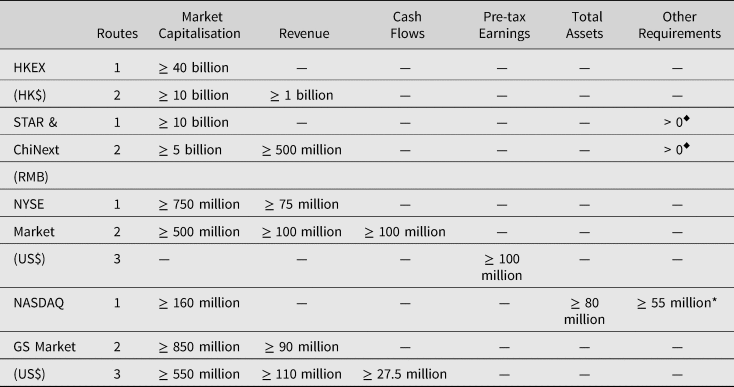

Higher Financial Threshold: DCSS usage on the SSE STAR Board must meet a high financial threshold through either of the following routes: (i) Pure Market Capitalisation Test: no lower than RMB ten billion in expected market capitalisation; or (ii) Market Capitalisation with Revenue Test: no lower than RMB five billion in expected market capitalisation with no less than RMB 500 million in revenue in the most recent year prior to listing.Footnote 72 It should be noted that, besides the valuation and revenue requirements, the SZSE ChiNext Board also requires DCSS issuers to have positive net profits.Footnote 73 Such financial requirements are overall harsher than that of the NYSE and NASDAQ premium segments (see Table 5).

Table 5. Comparison of the financial standards of DCSS usage in the US, China and Hong Kong

♦ positive net profits in the most recent year before listing (required by the ChiNext Board only).

* stockholders’ equity of no less than US$ 55 million.

Table drawn by the author. Source: SSE STAR Board Listing Rules, r 2.1.4; SZSE ChiNext Board Listing Rules, r 2.1.4; NYSE Listed Company Manual, r 103.01(B); NASDAQ Stock Market Rules, r 5315, and HKEX Main Board Listing Rules, r 8A.06.

Minimum Founder Shareholding: Chinese listing regimes require holders of superior voting shares (primarily, the founders) to own no less than 10% of the equity stake.Footnote 74 As discussed above, control abuse conducted by a rational person is subject to a cost-benefit analysis by comparing the potential loss from the downside of share value with the expected gains of private interests. Given this, the 10% minimum shareholding requirement can partly tie the founders’ equity interests with the company's share value to mitigate the incidence of opportunist behaviours.

Maximum Weighted Voting Ratio: China does not permit the maximum weighted voting ratio between per superior voting share and per inferior voting share to exceed 10:1,Footnote 75 given that the high/low vote ratio determines the extent to which a controlling shareholder can hold the minimum shareholding without losing control.Footnote 76

Minimum Public Votes: In China, DCSS issuers are required to grant inferior voting shares at least 10% of the total votes, whereby public investors can convene extraordinary general meetings to voice their opinions.Footnote 77

Information Disclosure: The Chinese listing rulebooks require DCSS issuers to warn investors of DCSS risks and the measures adopted for investor protection in the prospectus, articles of association and periodic financial reports.Footnote 78 Also, the lock-up arrangement of superior voting shares, transfer restrictions, the circumstances that would cease DCSS usage, and alteration of superior voting power should be disclosed,Footnote 79 which is essential for investors to make informed decisions.Footnote 80 In comparison, the US stock market does not make specific stipulations of disclosing DCSS usage and associated risks. However, due disclosure of various risks that may damage investors’ interests is a principle-based rule in the USFootnote 81 and, as such, most of the disclosure obligations written into the Chinese rules also fall into the disclosure scope in the US.

Anti-dilution Principle: To safeguard public investors, both the Chinese and US stock markets employ an anti-dilution provision, prohibiting DCSS issuers from diluting the voting power of public investors.Footnote 82 If dilution occurs through any corporate activity, eg the buy-back of OSOV shares, holders of superior voting shares must take appropriate actions to restore the dilution, such as by converting some superior voting shares to OSOV shares.Footnote 83

Breakthrough Principle: DCSS issuers in China are bound to a breakthrough principle that mandates superior voting shares to vote on the OSOV basis to weigh public investors’ voices more heavily than would ordinarily be the case in general meetings.Footnote 84 The circumstances that can trigger the re-ordering of voting rights normally involve key corporate matters, including the change of the articles of association, alteration of the rights attached to superior voting shares, appointment or removal of independent directors and audit firms, and corporate merger, split or dissolution.Footnote 85 The breakthrough principle is expected to limit the range in which superior voting power could be abused. For example, the election of independent directors on the OSOV basis can ensure director independence to counteract control abuse via board-level decisions.Footnote 86

Enhanced Corporate Governance Criteria: DCSS usage in China is subject to extra internal inspection for better corporate governance. Public limited companies incorporated in China are required to adopt a two-tier board structureFootnote 87 with the supervisors holding the powers to monitor directors and executives,Footnote 88 convene extraordinary general meetings and propose resolutions,Footnote 89 and file lawsuits against directors and executives in the event of fiduciary duty violation.Footnote 90 Upon introducing the DCSS, the supervisory board is entitled to play a larger role in counteracting agency risks, which can monitor whether the compliance-based rules specific for investor protection are obeyed or not and publish its opinions in annual reports.Footnote 91

Mandatory Sunset: Recent debates have tended to pivot less on ‘to be or not to be’ concerning the DCSS but more on a middle-ground issue, ie how should DCSS usage be subject to ‘sunset clauses’, which means that DCSS usage will cease if a given circumstance occurs.Footnote 92 China does not employ a time-based sunset requirement as a universal regulatory norm. However, unlike the US, which leaves the bespoke adoption of sunset circumstances to company-specific private ordering, China employs event-based provisions as public regulatory intervention to cease DCSS usage, such as where the beneficiaries of superior voting shares resign from the board or are incapacitated from performing director duties.Footnote 93 Besides, the private sale of superior voting shares is stipulated as a sunset event.Footnote 94 Since the DCSS anchors its value in enabling founders to counteract market short-termism, if superior voting shares are sold, the basis of employing a DCSS to achieve founder control would no longer be justified and thus the superior voting power granted to the founders should cease.

Most Chinese rules regulating DCSS usage have been transplanted from the HKEX.Footnote 95 In contrast, the US stock market adopts fewer ex ante regulatory measures other than the new issuer doctrine, information disclosure requirement and anti-dilution principle (see Table 6).

Table 6. The restrictions on DCSS usage in the US, China and Hong Kong

Table drawn by the author.

(b) The impact of the ex ante regulation on DCSS usage

Having recognised the jurisdictional disparity in ex ante regulation, this paper now explores its impact on DCSS usage in China and Hong Kong. For the purpose of comparative quantitative analysis, only two measurable aspects are examined, ie the dual-class listing financial criteria and the maximum weighted voting ratio. The empirical findings are as follows.

As shown in Table 2 above, from 13 June 2019 to 31 December 2021, 82 Chinese companies went public in the US, with the adoption of a DCSS by 47 of them. Through examining the prospectuses of the 47 US-listed Chinese DCSS issuers, this paper discovers that, of these, 12 did not meet the financial criteria of conducting a dual-class listing on the SSE STAR Board, and 13 issuers attached more than ten votes to each superior voting share, which was not permitted in China. In addition, eight of the 47 companies failed to meet both the maximum weighted voting ratio and the dual-class listing financial criteria of the SSE STAR Board. That is to say, the Chinese ex ante regulatory strategies blocked 33 of the 47 US-listed Chinese DCSS issuers (70.2%) from carrying out a dual-class listing on the SSE STAR Board.

Likewise, from 12 June 2020 to 31 December 2021, 56 Chinese companies were listed in the US, with the use of a DCSS by 31 of them. Of the 31 dual-class companies, 13 did not satisfy the financial criteria of using a DCSS on the SZSE ChiNext Board, and one was actually blocked from floating on the SZSE ChiNext Board due to attaching more than ten votes to its superior voting shares. Meanwhile, 15 companies failed to meet both requirements. That is to say, 29 of the 31 US-listed Chinese dual-class issuers could not have gone public on the SZSE ChiNext Board with a DCSS. This reveals that, compared to the regulation of the SSE STAR Board, the requirement of positive net profits of the SZSE ChiNext Board has further affected DCSS usage.

The empirical analysis of the Hong Kong stock market receives similar findings. From 30 April 2018 to 31 December 2021, of the 74 US-listed Chinese DCSS issuers, 28 did not meet the financial threshold of listings with a DCSS on the HKEX, and 15 companies attached more than ten votes to each superior voting share. In addition, 17 issuers failed to satisfy both requirements (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. The impact of ex-ante regulation on DCSS usage in the Chinese and Hong Kong stock markets

Figure drawn by the author.

From the empirical analyses above, it can be seen that while the ex ante regulatory strategies employed in China and Hong Kong can ringfence DCSS usage to issuers with high profile and relatively low governance risks to consolidate investor protection, the other side of the coin is that such restrictive rules have closed the Chinese and Hong Kong stock markets to certain Chinese issuers who have instead voted with their feet to go public in the US. In other words, the limited allowance has substantially affected DCSS usage in China and Hong Kong.

To say the least, assuming Chinese issuers take only the control issue into account when choosing the desired listing venue, ceteris paribus, can the introduction of the DCSS in China and Hong Kong considerably change the landscape of stock market competition with the US? It is hard to say, but the answer is probably negative. For one thing, the Chinese and Hong Kong bourses require superior voting shares to carry ten votes per share at most. By comparison, neither the NYSE nor NASDAQ requires a cap on the weighted voting ratio, exemplified typically by the allowance of non-voting shares. That is to say, the proportionality-distorting mechanisms in the US can grant Chinese issuers a higher level of control, compared to listing with a DCSS in China or Hong Kong.

For another, both the NYSE and NASDAQ exempt non-US companies from being bound to the new issuer doctrine, provided the company law of their home country allows the change of voting structure post listing.Footnote 96 The primary jurisdiction of incorporation of US-listed Chinese companies is the Cayman Islands, followed by the British Virgin Islands.Footnote 97 Both permit the reorganisation of share capital at any time subject to the approval of three-quarters of the total votes.Footnote 98 In practice, five US-listed Chinese companies (stock symbols: VIPS,Footnote 99 CCM,Footnote 100 NOAH,Footnote 101 SINAFootnote 102 and HEBTFootnote 103) converted their voting arrangements from the OSOV to DCSS post listing. Therefore, the US regime can grant Cayman/BVI-incorporated Chinese issuers greater flexibility in choosing the voting structure at the IPO stage, compared to going public domestically or in Hong Kong, where the new issuer doctrine is implemented without any exception. On these grounds, introducing the DCSS in China and Hong Kong seems unlikely to reshape the landscape of stock market competition with the US significantly, provided there are no other legal innovations to generate synergy effects.Footnote 104

5. Policy implications for involved jurisdictions and beyond

Drawing on the discussion above, it can be seen that in the US, permitting DCSS usage with the relatively lenient ex ante regulation has played an important role in accommodating Chinese issuers, although it may not be the only determinant.Footnote 105 In contrast, the Chinese and Hong Kong stock markets have employed many restrictive rules that have caused limited allowance to substantially affect DCSS usage. The diametrical viability and efficacy of the DCSS may suggest the necessity for China and Hong Kong to relax the harsh restrictions. However, this would prompt concern about competing interests, ie investor protection against DCSS perils. Given this, policy implications should be put in a broader context for consideration.

Investor protection relies on both ex ante regulation and ex post remedy,Footnote 106 which are to some extent complementary or alternative. It means that the availability of effective post-event remedy can decrease reliance on ex ante regulation, and vice versa. As clearly reflected by the US experience, the shortage of ex ante regulatory measures does not imply poor investor protection, which instead anchors its strength deeply in the ease and effectiveness of securities enforcement. In fact, China introduced a US-style securities class action mechanism, namely the special securities representative action (SSRA) mechanism, upon the modification of its Securities Law in December 2019.Footnote 107 Most recently, the first SSRA, ie China Securities Investor Services Centre v Kangmei Pharmaceutical Co, was ruled on by the court on 12 November 2021.Footnote 108 In this case, the wrongdoers were required to bear strict liabilities to pay compensation of RMB 2.459 billion to the affected investors, an amount even larger than the monetary settlement of the US securities class actions against Alibaba (US$250 million, equivalent to RMB 1.75 billion).Footnote 109 It is noteworthy that in the court decision of the first SSRA, the involved accounting firm and accountant were held to bear joint and several liability for their negligence. As such, it is expected that gatekeepers would perform gatekeeping duties prudently to find and avoid fraudulent activities so as to maintain market integrity. In addition, five independent directors were found liable for signing the annual reports without discovering the misconduct. Thus, the court decision has given a strong signal that independent directors must duly play their supervisory role rather than acting as little more than rubber-stamp authorities.Footnote 110 In this way, Chinese authorities have shown a strong determination to ensure investor protection.

Given the purpose of introducing the DCSS, the implementation of the SSRA mechanism has provided a basis for relaxing the harsh ex ante regulation of DCSS usage, thereby enhancing market attractiveness to issuers while not compromising investor protection. Such a policy implication may also make sense in Hong Kong, given that it has proposed the introduction of a class action regime.Footnote 111 However, this paper cannot say, on the basis of the existing empirical findings, what degree of restrictions are optimal for China and Hong Kong.

Reforming listing regimes to promote business success for social welfare is by no means a public policy concern specific to China and Hong Kong. Indeed, many other jurisdictions face similar challenges. Take the UK for example: the LSE Premium Main Market is materially under-represented by high-tech companies, largely due to the DCSS taboo.Footnote 112 Moreover, the LSE Premium Main Market experienced a significant decline (over 50%) in the number of listed companies in recent years.Footnote 113 Against this backdrop, the UK has reintroduced the DCSS on the LSE Premium Main Market to attract global issuers. Meanwhile, out of the consideration that public investors should be safeguarded against DCSS perils, several strict usage conditions have been adopted.Footnote 114 In the UK listed sphere, most issuers have a highly fragmented capital structure. Thus, although the PSS and SVA are permissible in the UK, they may not be used as adequate substitutes for the DCSS. This means that it is necessary to reintroduce the DCSS for the global competitiveness purpose. However, some of the ex ante regulatory measures, such as the mandatory time-based sunset requirement (ie five years post IPO) and restricting DCSS usage to blocking takeovers, are not well designed; this may considerably undermine the attractiveness of the LSE Premium Main Market to potential issuers.Footnote 115

The evidence finding and explaining the low efficacy of the DCSS in the Chinese and Hong Kong stock markets can provide some empirical lessons for the global listing community. First, it is not unwise for policymakers to consider the availability of substitutive control-enhancing instruments under their legal and regulatory frameworks that may, to a large extent, decide the necessity of introducing the DCSS. Otherwise, introducing the DCSS would be a rather pointless exercise if there is little demand. Secondly, in the event of visiting the DCSS, policymakers need to think hard about global competitiveness and strike a balance between market openness and investor protections, given that overly restrictive ex ante regulatory measures would undermine the benefits of the DCSS in fostering stock market attractiveness to issuers.

Conclusion

The DCSS can combine the advantages of public fundraising to expand the company with the maintenance of managerial autonomy and is thus attractive to founders. From the standpoint of stock markets, since founders usually have a decisive say on choosing the listing venue, permitting the DCSS may enhance their attractiveness to prospective issuers. Against the backdrop of financial globalisation, with the ever-expanding stock market competition, a growing number of jurisdictions have introduced the DCSS to attract issuers.

However, the empirical analyses of the Chinese and Hong Kong stock markets reveal that the DCSS does not necessarily help stock markets attract issuers. For one thing, owing to the fact that most Chinese issuers have block holders, DCSS usage may not be in high demand as expected because other control-enhancing instruments and ownership concentration have served well as substitutes to achieve founder control. For another, due to stringent ex ante regulation, many US-listed Chinese DCSS issuers could not have met the conditions for DCSS usage in China or Hong Kong. As a result, the DCSS has borne low viability and efficacy in China and Hong Kong in the post-reform era; this may encourage policymakers to think about relaxing the harsh ex ante regulation.

Drawing on the empirical lessons from the Chinese and Hong Kong stock markets, for other jurisdictions at the crossroad of (re)visiting the DCSS, it is not unwise for policymakers to ponder both the availability of substitutive control-enhancing instruments under their legal frameworks and the balance they aim to strike between investor protection and market openness.