What is commonly known as the “Third Indochina War” consists of two related wars: the Vietnam–Kampuchea War from 1978 to 1990 and the brief Sino-Vietnamese War in February 1979. Although the latter military confrontation was brief, China and Vietnam were technically at war until the resolution of the Cambodian conflict in 1990. Unlike the “First” and “Second” Indochina Wars which lasted just as long, “the post-1975 period in general and the Third Indochina War in particular continue to be relegated to footnotes and epilogues.”Footnote 1 Although Edwin Martini made this observation in 2009, the state of the field has not changed much today.

Marshaling old and new Vietnamese, Cambodian, Chinese, Soviet, American, and Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) sources, this chapter takes an international-history perspective, focusing on the simultaneous decision-making of all sides directly or indirectly involved in the conflict, which, in the words of Odd Arne Westad, “created shockwaves within the international system of states.”Footnote 2 It adopts a chronological approach, following the life cycle of the conflict by first locating the origins of both wars from the interconnected perspectives of the three main protagonists – Vietnam, Cambodia, and China. Following that, the chapter will describe the conduct of both wars and their eventual resolution. This is where the Soviet Union, the United States (and its European allies), and ASEAN come into the picture. Although these actors were not directly involved in the fighting, they played a significant role in both prolonging the war and bringing about its end.

When it comes to the English-language historiography of the Third Indochina War we know a lot more about the Khmer Rouge – their origin and roots, ideology, policies and practices, and relations with Vietnam – from the scholarship of Ben Kiernan, Steven Heder, and David Chandler; about the root problems in Sino-Vietnamese relations culminating in the February 1979 war from noted Vietnam historian William Duiker, Chang Pao-min, King C. Chen, Eugene K. Lawson, Robert S. Ross, Anne Gilks, and Steven J. Hood. These studies, mostly by political scientists (David Chandler and William Duiker being the exceptions), were mainly published in the 1980s and were based primarily on contemporary information or open sources. Three of the best accounts of the conflict are: Grant Evans and Kelvin Rowley’s Red Brotherhood at War: Indochina since the Fall of Saigon; Nayan Chanda’s Brother Enemy: The War after the War; and Stephen J. Morris’ Why Vietnam Invaded Cambodia: Political Culture and the Causes of War. Then there was a long lull before the publication of The Third Indochina War: Conflict between China, Vietnam and Cambodia, 1972–79 edited by Odd Arne Westad and Sophie Quinn-Judge,Footnote 3 which essentially focuses on developments in the 1970s leading to the conflict but does not really come to grips with the two key questions: Why did Vietnam launch its invasion of Cambodia (then known as Kampuchea) on December 25, 1978? And why did China attack Vietnam on February 17, 1979 and withdraw a month later? Bringing this overview of the state of the field to a close are three recent books published in 2014, 2015, and 2020 respectively: Brothers in Arms: Chinese Aid to the Khmer Rouge 1975–1979 by Andrew Mertha; Deng Xiaoping’s Long War: The Military Conflict between China and Vietnam 1979–1991 by Xiaoming Zhang (which is useful to read alongside Edward C. O’Dowd’s Chinese Military Strategy in the Third Indochina War: The Last Maoist War); and, the most recent, Kosal Path’s Vietnam’s Strategic Thinking during the Third Indochina War, which has a chapter on Vietnam’s decision to invade Cambodia in which he argues that the geopolitics (the alliance between Democratic Kampuchea and China backed by the United States) was a more significant reason for the war than the border conflict and the historical animosity between Cambodia and Vietnam.Footnote 4

Vietnam–Cambodia Relations, 1962–75

Phnom Penh fell to the Khmer Rouge on April 17, 1975, about two weeks ahead of the Vietnamese communists who captured Saigon on April 30. The timing was deliberate on the part of the Khmer Rouge, to make the point that they can achieve victory without Vietnamese assistance and in fact even quicker. Relations between the Vietnamese communists and the Khmer Rouge gradually but consistently deteriorated after Pol Pot took over the leadership of the Khmer Rouge in July 1962. The Khmer Rouge had for many years been constrained by both Hanoi and Beijing, which favored the strategy of supporting Norodom Sihanouk because he turned a blind eye to Vietnamese communist activities along the border. The March 1970 coup against Sihanouk by the pro-American Lon Nol changed everything. Thereafter, the Khmer Rouge demonstrated greater autonomy and assertiveness vis-à-vis Hanoi. The movement was not, however, completely unified in its stance. There were differences between the Saloth Sar (aka Pol Pot) group, who wanted a revolutionary overhaul of Cambodian society, and detractors, who aspired to restore Sihanouk to power. The latter group was more in line with Vietnamese and Chinese thinking. Hanoi had great difficulty managing its relations with the Khmer Rouge thereafter. In fact, as Vietnamese communist forces were withdrawing from Cambodia in the days before the signing of the Paris Agreement on Vietnam in late January 1973, the Khmer Rouge attacked them. On January 26, 1973, when Vietnamese paramount leader Lê Duẩn met the senior Khmer Rouge official known as “Brother Number Three,” Ieng Sary, in Hanoi to inform him that North Vietnam would sign the Paris Agreement the next day, he tried unsuccessfully to persuade the Cambodian Communist Party to coordinate its strategy with North Vietnam. Pol Pot was adamant that the fighting must continue and that there would be no truce with the Lon Nol regime and/or the United States. Pol Pot was afraid that the United States and Sihanouk might cut a deal behind his back. To Pol Pot, the Vietnamese communists’ deal with Washington was simply a sellout. Because North Vietnam’s top priority was the war, the Hanoi leadership tried to play down its problems with the Khmer communists.Footnote 5

The reality, as Sihanouk confided to the French ambassador to China after returning from a brief visit to the communist-controlled area of Cambodia in late March–early April 1973, was that anti-Vietnamese feelings within the Cambodian Communist Party were rapidly growing. Sporadic fighting between both sides occurred soon after Sihanouk’s visit. As long as the “revolution” had not been won, both sides were cognizant of the fact that they still needed each other. The withdrawal of the Vietnamese communists from Cambodia after the signing of the Paris Peace Accord inadvertently provided the opportunity for Pol Pot and those who supported him, who had always wanted to get out of Vietnam’s shadow, to liberate the country ahead of the Vietnamese. A revised history of the Cambodian Communist Party published in 1974 hardly mentioned Vietnam. Phnom Penh fell on April 17, 1975. We still do not know what the Vietnamese leadership thought of the liberation of Cambodia, which occurred while they were deeply engrossed in their own war in southern Vietnam.Footnote 6

In the months after April 1975, both countries had their hands full putting their own houses in order. Attention at the beginning was essentially focused, understandably so, on internal developments and putting in the structures to realize their respective vision(s) of a socialist or communist society. As for relations between Vietnam and Cambodia, it remained unchanged from what it was pre-April 1975 – poor, but nowhere near the brink of a total breakdown.

This is perhaps a good point to pause and briefly consider the idea of the “Indochina Federation.” There were apparently two schools of opinion within the Vietnamese communist movement on the issue of its relations with Cambodia and Laos. One was for a unified Indochinese communist party, with Vietnam assuming the role of a big brother. The other advocated a loose form of unity between the three Indochinese countries whereby assistance could be given to each other as and when the need arose. This was the arrangement that the Chinese favored, whereas Lê Duẩn and his closest associates were for a unified communist movement led by Vietnam. In the minds of Lê Duẩn and those close to him, it was the Chinese who had forced them to accede to the French demand that the problems of Cambodia and Laos be separated from those of Vietnam at the 1954 Geneva Conference on Indochina.Footnote 7 Although most Vietnam specialists have concluded that the idea of an Indochina Federation was abandoned in the late 1930s, there is no doubt that Vietnam continued to retain a neocolonialist attitude toward both Cambodia and Laos. The Khmer Rouge perspective of Vietnam as having always wanted to annex and swallow Cambodia, as well as exterminate the Cambodian race, was the most extreme. As the Black Book (issued by the Khmer Rouge in September 1978) pointed out, one of the means by which the Vietnamese hoped to achieve their goal was through the strategy of an “IndoChina Federation.”Footnote 8

Vietnam–China Relations, 1971–5

The twists and turns in Vietnam–China relations share some parallels with the relationship between Vietnam and Cambodia. That relationship, which had never been really warm, turned complicated in July 1971 (coincidentally around the time when relations between the Khmer Rouge and the Vietnamese communists were turning bad) with the announcement of US President Richard Nixon’s forthcoming visit (to take place in May 1972) to Beijing. The Vietnamese were informed on July 13, by Zhou Enlai, who had traveled to Hanoi to personally convey the news, two days before the rest of the world would learn of it. Sino-Vietnamese relations gradually declined from this point. Although Chinese influence remained strong in North Vietnam for the duration of the Vietnam War, it had diminished considerably by 1973 as a result of Sino-US rapprochement.Footnote 9

The high profile given to senior Khmer Rouge official Khieu Samphan’s April 1974 visit to Beijing, where he met Mao Zedong, contrasted with the low-key publicity of Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRVN) Prime Minister Phạm Vӑn Đồng’s visit in the same month, adding fuel to the already strained Sino-Vietnamese relations. Vietnamese Workers’ Party (VWP) Politburo member and DRVN Deputy Prime Minister Lê Thanh Nghị’s two visits to Beijing in August and October 1974, respectively, extracted little economic and military assistance from China. Significantly, by August 1974, because of health reasons, Zhou Enlai was no longer able to oversee Sino-Vietnamese relations.Footnote 10 Zhou underwent surgery for cancer in June 1974 and was last seen at an official function in January 1975. After that, he effectively retired for medical treatment and died in January 1976.

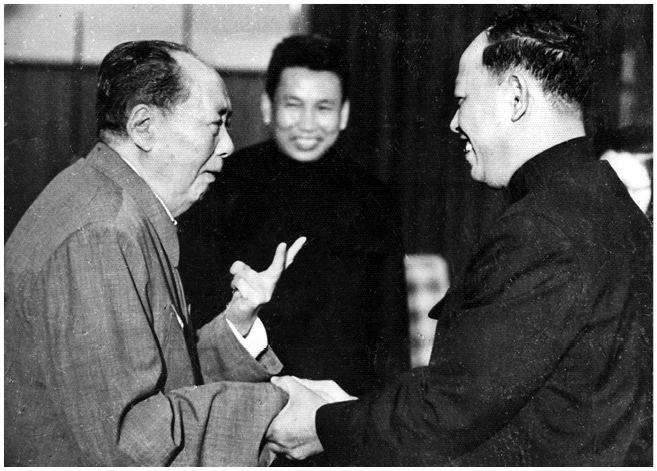

Figure 15.1 Chairman Mao Zedong greets Khmer Rouge Foreign Minister Ieng Sary while Khmer Rouge leader Pol Pot looks on (1970s).

Pol Pot’s visit to Beijing in June 1975 was, however, well received by the Chinese, and Mao lavished much praise on Pol Pot and the success of the Khmer Rouge. Pol Pot, for his part, projected himself as an ideological disciple of Mao. As Qiang Zhai noted, “realising the determination and strength of the Khmer Rouge, Chinese leaders had apparently taken the position that if they wanted to maintain their influence over the Vietnamese and the Russians in Cambodia, they must back Pol Pot.”Footnote 11 Lê Duẩn’s first visit to Beijing in September 1975, not long after the unification of Vietnam, was also in sharp contrast to that of Pol Pot’s visit in June. Most significantly, the Vietnamese leadership’s refusal to accept Mao’s “Three Worlds” theory, which required Hanoi to oppose the Soviet Union, affected Sino-Vietnamese relations. The Khmer Rouge, on the other hand, never managed to develop a close relationship with Moscow.

The “battle lines” were thus more or less drawn by the end of 1975. Sino-Vietnamese and Vietnam–Kampuchean relations became interweaved. At the 4th Congress of the VWP in December 1976, the VWP merged with the Southern-based People’s Revolutionary Party of Southern Vietnam to create the Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV). At the same meeting, all the ostensibly pro-China groups, as well as those who had reservations about a unified Indochinese communist movement under Vietnam’s leadership, were purged. Sino-Vietnamese relations went quickly downhill from then and did not recover until the 1990s. The harsh treatment of ethnic Chinese by Hanoi and border issues between Vietnam and China that emerged in 1977 were thus mere symptoms or consequences of a much deeper malaise.

Vietnam–Kampuchea Relations, 1975–7

Newly independent countries are especially sensitive about their territorial integrity. Both Vietnam and Cambodia had land and maritime border problems or disagreements that resulted in sporadic skirmishes soon after April 1975. Between that time and December 1977, the Vietnamese did make a number of attempts to settle the border dispute. In June 1975, Phan Hiền met with Kampuchean officials, and both sides agreed to the establishment of provincial liaison committees to resolve their problems at the local level and, if that failed, to raise the issues to higher authorities. In the same month, Pol Pot led a delegation to Hanoi to discuss the Vietnamese seizure of the Cambodian island of Poulo Wai, which was subsequently returned to the Kampucheans in August. Lê Duẩn had traveled to Phnom Penh in August for further discussions on the border disputes. It was reported in the Vietnamese media that both sides reached a “complete identity of views,” but it was short-lived. The reason their border disagreements (which were by no means irreconcilable) could not be resolved and instead grew out of hand was the ongoing power tussle within Kampuchea in 1976–7 that finally saw Pol Pot (the arch-anti-Vietnamese) and his faction or clique emerge as the dominant power in the country in September 1977. It is difficult to go into the specifics of the divisions within the Khmer Rouge. As Bern Schaefer, who has explored the East German archives, noted, the Vietnamese incessantly complained to their East German counterparts that it was hard to determine the real background of the Khmer defectors or cadres because “their files have been destroyed.”Footnote 12 Memoirs by Khieu Samphan (president of Democratic Kampuchea 1976–9)Footnote 13 and Heng Samrin (head of state of the Vietnamese-backed People’s Republic of Kampuchea 1979–81 and General Secretary of the Khmer People’s Revolutionary Party 1981–91) reveal to some extent the schism in the Khmer Rouge regime and the extermination by Pol Pot of those seen as aligned with the Vietnamese.Footnote 14

Because the border issues remained unresolved, except for the brief lull between mid-1975 and 1976, the fighting continued, and this grew from skirmishes to increasingly large-scale clashes, particularly from late September 1977. According to Bùi Tín, the fighting became progressively more severe especially after a massacre at Châu Đốc on the night of April 30, 1977, which was also the second anniversary of the fall of Saigon.Footnote 15 In September 1977, the intensified border conflict coincided with Pol Pot’s highly publicized and triumphant visit to China, where he was warmly welcomed by Hua Guofeng, Mao’s successor. His visit was preceded by a lengthy speech revealing the existence of the Communist Party of Kampuchea and extolling its singular role in the revolutionary struggle. Hanoi tried to get the Chinese to mediate without success. The warm welcome of Pol Pot and the Chinese failure to mediate – it is not clear whether it was a case of unwillingness or inability – created the impression, in the eyes of the Vietnamese, that Beijing supported Khmer Rouge actions. According to Soviet sources, the presence of Chinese military personnel training and arming the Khmer Rouge, and building roads and military bases, including an air force base in Kampong Chhnang that made it possible for military planes to reach Hồ Chí Minh City in half an hour, forced the Vietnamese “to think about the real threat to [their] security rather than about an Indochinese federation.”Footnote 16 In addition, on July 18, 1977, a Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation was signed between Vietnam and Laos. Vietnam thus consolidated its “special relationship” with Laos with little opposition. In the view of Hanoi, if it were not for Beijing’s conspicuous support for the Khmer Rouge, Phnom Penh would have followed the path of Vientiane. China was thus seen as the obstacle preventing the Vietnamese from realizing their aspiration of an Indochinese Federation – a repeat of what happened in 1954.

On September 30, 1977, there was a Politburo meeting in Hồ Chí Minh City chaired by Lê Duẩn to evaluate the situation. The Politburo came up with two options: (a) facilitate a victory of the “healthy,” namely pro-Vietnam forces inside Cambodia; or (b) pressure Pol Pot to negotiate in a worsening situation. The first (opening) move to achieve either option was to modify Vietnam’s border-war strategy from defensive to offensive. The Vietnamese made one further, and futile, attempt to get the Chinese to intercede with the Khmer Rouge when Lê Duẩn met with the Chinese leadership in Beijing in November. The November meeting also showed the strains in Sino-Vietnamese relations.Footnote 17 On December 25, 1977, to the surprise of the Khmer Rouge, Vietnamese forces invaded eastern Cambodia and briefly occupied the territory, in retaliation for the Khmer Rouge attack on Tây Ninh province in September, before withdrawing.Footnote 18 It was clearly an exercise of intimidation and a warning to the Khmer Rouge. Not to be cowed, Phnom Penh also surprised the Vietnamese by breaking off diplomatic relations on December 31, 1977. The tensions and dispute between the two fraternal communist countries, which had been kept away from the limelight, finally became public.

Why did the Vietnamese not go all the way in December 1977, stopping 24 miles (39 kilometers) from Phnom Penh, and then withdrawing and waiting another twelve months before invading the country? One reason was that in 1977–8 there were some members of the party who held the view that “the contradictions between the US and China would prevent the formation of an anti-Soviet and anti-Vietnamese alliance,” and as such the anti-Maoists led by Deng Xiaoping in China would eventually choose the Soviet Union, and Vietnam by extension, over the United States.Footnote 19 These people would need to be convinced or neutralized. Thus, we first need to consider the state of Vietnam’s relations with the Soviet Union and the United States until the end of 1977 before focusing on the critical year 1978.

Vietnam–Soviet–US–China Relations, 1975–7

While the Vietnamese communists also had their disagreements with the Soviets – they continued to refrain from siding with the Soviet Union in the Sino-Soviet ideological dispute, and they continued to procrastinate over joining the Moscow-led Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (COMECON) – the 1973 annual report by the Soviet Embassy in Hanoi on the relationship between the two countries was, overall, positive.Footnote 20 Sino-Vietnamese animosity clearly played into the hands of the Soviet Union, which seized the opportunity to increase its influence in Vietnam.

As for the United States, Hanoi was keen to normalize relations with Washington after the 1973 Paris Peace Accord, but circumstances were not propitious. While the American military might have withdrawn from Vietnam, the war had not really ended. Shortly after the fall of Saigon in April 1975, Prime Minister Phạm Vӑn Đồng extended a formal invitation to the United States to normalize relations on one precondition: Washington must fulfill its commitment to provide reconstruction aid to Vietnam as stated in Article 21 of the 1973 Paris Peace Accord. The Ford administration, however, was only prepared to discuss normalization of relations without any precondition. Aid would be considered only once the American side was satisfied that the Vietnamese were seriously addressing the missing in action (MIA) issue, a high-priority concern for Washington. Thus, for the first one and a half years after the fall of Saigon (May 1975–December 1976), the two sides were locked into inflexible stances. There was one further reason the Ford administration was not forthcoming with the Vietnamese, which was that “Vietnamese–American normalization would have hampered US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger’s geopolitical strategy.” Kissinger’s foremost concern was, and always had been, the balance of US–Soviet relations and the strategic importance of the China factor in the equation. As Steven Hurst put it, “easing Chinese fears of Soviet–Vietnamese collusion would have reduced the incentive to normalize with the United States on terms acceptable to Washington.”Footnote 21

The arrival of a new president in the White House appeared to provide both sides with a fresh opportunity to revisit the issue of normalization of relations. The State Department’s perspective on and approach to relations with Hanoi differed from Kissinger’s. As mentioned above, the new US secretary of state, Cyrus Vance, and his assistant for Far Eastern and Pacific affairs, Richard Holbrooke, placed ASEAN at the core of American policy in Southeast Asia. In the case of Vietnam, they saw it as a country “trying to find a balance between overdependence on either the Chinese or the Soviet Union,” thus offering “an opportunity for a new initiative.” It was in America’s interest, Vance believed, to wean Vietnam of its dependence on China and the Soviet Union.Footnote 22 The Carter administration, however, shared the same position as that of its predecessor – that reconstruction aid, which the Vietnamese wanted, could only be discussed after the MIA accounting had been satisfactorily concluded. This did not appear to be a difficult task, since the House Select Committee on Missing Persons in Southeast Asia, which delivered its final report in late 1976, concluded that there were no American POWs alive in Indochina. The American side was hopeful of a quick agreement. But negotiations in 1977 to bring about normalization still failed, because Hanoi insisted that the United States was legally bound to provide aid. And as a rebuke to Washington’s refusal to fulfill what the Vietnamese considered to be its legal obligation, Hanoi stubbornly refused to bring the MIA accounting to a close. Subsequent dropping of such words and terms as “precondition,” “legal,” “delinking of aid,” “MIA,” and “normalization” became verbal gymnastics. The bottom line was the Vietnamese continued to expect American aid, which they badly needed, as a precondition for normalization. After the failure of the March and May 1977 meetings, there were no more substantial discussions. In October, Deputy Foreign Minister Nguyễn Cơ Thạch met Holbrooke during the United Nations (UN) General Assembly, and both agreed to meet for further talks to find a compromise solution. Subsequently, Phan Hiền and Holbrooke met in Paris from December 7 to December 10, 1977, but could not resolve their differences.

Meanwhile, the Hanoi leadership was pleased to see the fall of the Gang of Four in Beijing in October 1976. Although, unlike Hồ Chí Minh, Lê Duẩn had never been close to the Chinese leadership, he expected that Sino-Vietnamese relations would improve under Deng Xiaoping.Footnote 23 However, Deng, unlike Zhou Enlai, did not have any particular attachment to the Vietnamese. As Qiang Zhai put it, “this absence of emotional ties to the Vietnamese and a visceral bitterness about what he perceived as Hanoi’s ungratefulness and arrogance help explain why he had no qualms about launching a war in 1979 ‘to teach Vietnam a lesson.’”Footnote 24 By the end of 1977, the only country that Vietnam could count on, if push came to shove, was the Soviet Union.

Vietnam–Kampuchea, 1978

In Kampuchea, attempts to organize Pol Pot’s overthrow by a mutiny of the Eastern Zone military forces (aligned with Vietnam) ended in a complete disaster for the anti–Pol Pot rebels in June 1978. That led to the Vietnamese decision to invade Kampuchea. The worsening of Sino-Vietnamese relations corresponded with the rupture in Vietnam–Kampuchea relations. Chinese public statements in 1978 clearly showed that Beijing’s sympathies lay with the Khmer Rouge regime. China suspended all aid to Vietnam at the end of May 1978 and recalled all its specialists in the country on July 3. Vietnam joined COMECON on June 29. Finally, at the 4th Plenum of the CPV Central Committee in July 1978, a resolution was passed identifying China as Vietnam’s primary enemy.

By the summer of 1978, the “battle lines” had widened, with Vietnam and the Soviet Union on the one side, and Kampuchea and China on the other. Chinese Foreign Minister Huang Hua, in a May 1978 conversation with President Carter’s national security advisor, Zbigniew Brzezinski, succinctly described the Chinese perspective of developments in Indochina. This was a “problem of regional hegemony”; Vietnam’s goal was to dominate Kampuchea and Laos and establish the Indochinese Federation, and “behind there lies the Soviet Union.” Rightly or wrongly, the Chinese saw Moscow as supporting, if not directing, Vietnamese regional aspirations. Vietnam had already achieved its dominance over Laos but was encountering difficulties in Cambodia. Vietnamese–Kampuchean tensions were “more than merely some sporadic skirmishes along the borders.” They constituted a major conflict that “may last for a long time,” that is, as long as Vietnam persisted in realizing its goal.Footnote 25

A Beijing official presumably told Nayan Chanda that during one of the regular Chinese Politburo meetings in July 1978, the leadership decided in “absolute secrecy” to “teach Vietnam a lesson” for its “ungrateful and arrogant behaviour.” Apparently, this issue had already been raised at the May 1978 Politburo meeting. There were some who disagreed, but Deng Xiaoping was able to make a persuasive case by arguing that: (a) limited military action would demonstrate to Moscow that China “was ready to stand up to its bullying”; and (b) Moscow would not want to get militarily involved. The Chinese idea was to frame the military action as part of a “global antihegemonic strategy serving broader interests,” rather than just a bilateral conflict between Vietnam and China. For this, Beijing first needed to improve its relations with the United States, noncommunist Asia, and the West. As for when to punish the Vietnamese, the decision would be made at the appropriate time.Footnote 26 In August 1978, the Chinese advised Pol Pot to prepare to wage a protracted war. Vietnamese Foreign Minister Nguyễn Cơ Thạch claimed that Vietnam signed the treaty with the Soviet Union only after China began to concentrate its military forces on the Vietnamese border and made serious preparations for an invasion.Footnote 27

We will recall that the Vietnam–US negotiations to normalize relations that had been held up until the end of 1977 were unsuccessful. In May 1978, Vietnam tried to resuscitate the normalization discussions by hinting that it would drop its long-held precondition of reconstruction aid.Footnote 28 But the Vietnamese vacillated on this until late September 1978, before Nguyễn Cơ Thạch finally confirmed it. By this time, the “window of opportunity” was already fast closing. In April 1978, President Carter had given permission to National Security Advisor Brzezinski to visit Beijing, which he did in May. It was, in Carter’s view, a “very successful” trip.Footnote 29 Like Kissinger, Brzezinski aimed to balance US–Soviet relations and the strategic importance of China in this equation. Normalization of relations with Vietnam was secondary on his agenda. Brzezinski’s view differed from the State Department’s. Thanks to the support of President Carter, he prevailed. Besides Brzezinski, the tensions between Vietnam and Kampuchea, Vietnam’s joining of COMECON, and China’s opposition all worked against Vietnam. John Holdridge recalled that in September 1978, about the time that he was assigned to be national intelligence officer for China, he became aware of “the tremendous influence that Vietnam and Cambodia exercised on US–China relations.”Footnote 30 After the Vietnamese dropped their precondition, Washington agreed to normalize relations – but in 1979, and not before Sino-US normalization had taken place in December 1978. Carter made the decision on October 11 to focus on China. Thus, by mid-October 1978, Hanoi knew that Washington’s priority was China and that Vietnam–US normalization would not happen any time soon. This, plus the failure of both Foreign Minister Nguyễn Duy Trinh (late 1977 and early 1978) and Prime Minister Phạm Vӑn Đồng (in September–October 1978) to improve relations with ASEAN countries, compounded Vietnam’s sense of insecurity and reaffirmed the view that the Soviet Union was the only country it could rely on. Soon after, on November 3, Vietnam signed the Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation with the Soviet Union. According to Stephen J. Morris, there is no evidence that Moscow instigated or urged the invasion of Kampuchea.Footnote 31 But this does not mean that Moscow was not aware of Hanoi’s intention. Nor did they attempt to discourage the Vietnamese.

By late November 1978, when the rainy season had ended, most observers expected a large-scale attack of Kampuchea by the Vietnamese. Defense analysts in Singapore were of the view that Hanoi had two options: an all-out invasion leading to the capture of Phnom Penh and the occupation of Kampuchea, or “a more prudent military option,” which was to close in on the Khmer Rouge troops deployed along the border and destroy or disperse them without occupying the whole country. The destruction of this army would enable pro-Vietnamese Kampuchean armed forces to occupy Kampuchean territory with relative ease while Pol Pot’s troops were engaged with the Vietnamese Army. The first option was likely to provoke a major Chinese military response. No one could predict for certain whether the recently signed defense treaty between the Soviet Union and Vietnam would deter the Chinese. An all-out invasion would also likely damage Hanoi’s standing in the Third World. ASEAN states would surely view it as “naked aggression,” and Japan and the West would be “greatly disturbed” and be less inclined to give aid to Vietnam.Footnote 32 In the end, Vietnam chose the first option, believing that “in two weeks, the world will have forgotten the Kampuchean problem.”Footnote 33 In retrospect, and as the Vietnamese themselves subsequently admitted, that was a strategic mistake.Footnote 34

Preparation for the invasion of Kampuchea began in earnest in early December. On December 7, 1978, the People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN) was given the go-ahead to activate what was called the “General Staff’s Combat Readiness Plan for Cambodia.” The order of battle comprised 18 divisions, 600 armored vehicles, 137 aircraft, and as many as 250,000 men. The invasion was scheduled to begin on January 4, 1979, when the rice harvest was ready and the terrain dry. However, the Khmer Rouge caught wind of the impending invasion and launched a preemptive strike across the southwestern border of Vietnam on December 23, prompting Hanoi to bring forward its plan to December 25, although the PAVN was not yet completely ready. The Khmer Rouge preemptive action gave Vietnam a convenient pretext to retaliate.

Although the Vietnamese military conducted an “efficient and effective campaign” overall, the Khmer Rouge “put up a tenacious fight while withdrawing,” inflicting heavy losses on advancing PAVN armored units.Footnote 35 The Vietnamese took Phnom Penh on January 7 “virtually without a shot,” ending the violent, genocidal reign of the Khmer Rouge.Footnote 36 However, Hanoi’s plan to “free” Sihanouk (who had been kept under house arrest by Pol Pot) so that he could head – and legitimize – a “Cambodian liberation front” backed by the Vietnamese was foiled by Pol Pot, who released the prince on January 5. Sihanouk left for Beijing the next day. On January 10, 1979, the pro-Vietnamese People’s Republic of Kampuchea (PRK) was established in Phnom Penh, with Heng Samrin as the head of state.

The Sino-Vietnamese War and the Regional Response

The Chinese launched an attack on Vietnam on February 17, 1979.Footnote 37 The Chinese attack did not surprise ASEAN countries. Singapore leader Lee Kuan Yew recalled in his memoir that when Deng Xiaoping visited his country in November 1978, a possible Vietnamese invasion of Kampuchea was very much on the Chinese leader’s mind, and in Lee’s as well. He probed Deng on the Chinese response if indeed the Vietnamese crossed the Mekong River. From the conversation with Deng, he concluded that China would not sit idly by.Footnote 38

While ASEAN countries felt that Vietnam could not be let off the hook without repercussions, none could officially support the Chinese action for the same reason that they could not support Vietnam’s invasion of Kampuchea.Footnote 39 Having strongly opposed the Vietnamese invasion of Cambodia, ASEAN countries had a problem “coming to terms” with the Chinese invasion. ASEAN “could not reasonably endorse” the Chinese action. Fortunately, Chinese troops withdrew a month after the attack, “and so ASEAN was let off the hook.”Footnote 40 Singapore was of the view that “by combining diplomatic moves with military pressure against Vietnam, China had brought about the isolation of Vietnam and her economic impoverishment.”Footnote 41 Lee Kuan Yew, who found the Vietnamese so tough even in defeat, was thankful that the Chinese had punished the Vietnamese.Footnote 42 But in the wake of the attack, Mushahid Ali, deputy director (international) covering China at the ministry of foreign affairs, recalled that Singapore was concerned about how far and long China would pursue its “punishment” of Vietnam, and the regional repercussions of all that. Thailand was less troubled by the Chinese action.Footnote 43 Whatever the reservations some quarters of the Thai leadership might have had about China, they needed the support of Beijing (and Washington) against the Vietnamese. On the other hand, the attack “enhanced the suspicions” that Malaysia and Indonesia already had of Beijing. They were also concerned about the growing Sino-Thai relationship.Footnote 44 Malaysian Minister of Home Affairs Ghazali Shafie noted in a November 1979 speech on “Security and Southeast Asia” that Beijing was trying “to get the Soviets committed further and further into the bottomless pit in which the United States found herself once in Vietnam.” The Chinese needed to make the Soviets “bend and bleed” for aiding the Vietnamese until they could not withstand the strain any more, and then they “would lose Indochina altogether.” When that happened, “China would be free to pursue her own ‘hegemonism’ in Asia.”Footnote 45 Malaysian Deputy Prime Minister Seri Mahathir Mohammed noted that “perhaps China’s invasion did have a salutary effect on Vietnam but it also demonstrated unequivocally the willingness of China to act regardless of the usual norms of world opinion.”Footnote 46 On March 5, China announced the beginning of its troop withdrawal from Vietnam after having achieved its objective. All Chinese troops were withdrawn by March 16. Although the Soviet Union did not come to the aid of the Vietnamese during the war, the Soviet military presence in Vietnam accelerated thereafter.Footnote 47

Termination of War

Notwithstanding their distrust of China, the ASEAN states collaborated with the Chinese to oust the Vietnamese from Cambodia. The task of terminating the war began almost immediately after the invasion. The initiative was taken by ASEAN. On January 12, 1979, a special ASEAN foreign ministers’ closed-door meeting was convened in Bangkok, capital of Thailand, the country most anxious to discuss the invasion owing to the implications of the Vietnamese invasion, given the Thais’ geographical proximity and role during the Vietnam War. This meeting marked the beginning of the decade-long process to bring the war to an end. ASEAN, however, did not envisage a military solution to the conflict.

Because the two main protagonists were supported by China and the Soviet Union, respectively, there could be no solution as long as China and the Soviet Union were involved in protecting their respective interests. Of the two, the Soviet Union carried a heavier burden, having essentially to bankroll the Vietnamese. Thus, it would be up to the Soviets to decide the cost factor. Without Soviet assistance, Vietnamese determination would reach its limits.Footnote 48 Beijing concurrently aimed to isolate Vietnam and impose heavy costs on the Vietnamese for the invasion. Indeed, for years afterwards, Vietnam, still recovering from the Vietnam War, was forced to support considerable forces on its northern border to forestall a possible second Chinese attack.Footnote 49

The chessboard was further complicated by the involvement of the United States. ASEAN members believed that the United States was the only country that could provide aid to the noncommunist side matching that of the Soviet Union to Vietnam or of China to the Khmer Rouge.Footnote 50 However, there were few expectations of the American role at the initial stage. The United States had not overcome the “Vietnam syndrome.” Besides, American officials were doubtful of the capabilities of the noncommunist forces, as well as being skeptical of ASEAN’s ability to stay the course. In December 1981, the Reagan administration for the first time agreed to provide the noncommunist Khmers with “administrative and financial propaganda and other nonlethal assistance.” The amount was, however, insignificant compared to US aid to other parts of the world.Footnote 51 Washington also did not want to dispense aid directly.

The processes of glasnost and perestroika initiated by Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev and the eventual withdrawal of Soviet forces from Eastern Europe that led to the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1990, as well as the ending of the Sino-Soviet dispute, transformed the global geopolitical situation against which the Cambodian problem had been played out. The Soviet defeat and withdrawal from Afghanistan presaged the Vietnamese withdrawal from Cambodia in 1989.Footnote 52

The stalemate over Cambodia lasted until around 1986–7, when there was a flurry of political and diplomatic activities aimed at finding a political solution. Whereas in the past the Vietnamese had always insisted that the situation in Kampuchea was “irreversible,” Hanoi now expressed a willingness to reach a solution by political means. After years of no communication between the Coalition government of Democratic Kampuchea (CGDK)Footnote 53 and the Vietnamese-installed PRK, Sihanouk and Hun Sen met for the first time at the end of 1987. They accepted two-stage talks – first amongst the various Khmer factions and then amongst Vietnam and other interested countries. In effect, the Sihanouk–Hun Sen talks were proxy talks with Vietnam. The Soviet Union had in the past refused to discuss the Kampuchean problem on the grounds that it was not involved. Now, Moscow, under Gorbachev, demonstrated a willingness to play a helpful role in the seeking of a political solution. Moscow’s change of mind coincided with new developments within Vietnam. There was, within the Vietnamese leadership echelon, “a reappraisal of [Vietnam’s] endemic poverty and its performance vis-à-vis the relative prosperity and dynamism elsewhere in Southeast Asia.”Footnote 54 Indeed, the reassessment began as early as 1984, which accounted for Hanoi’s first announcement that it was prepared to withdraw forces as early as 1985 (which, of course, no one wanted to believe).

Conclusion

The Soviet Union completed its withdrawal from Afghanistan in February 1989, and the first Sino-Soviet summit since 1959 was held in May that same year. Even the United States, which had been rather uninterested in the Cambodian problem, was willing to discuss the issue with the Soviet Union at summit level. China, which as late as 1988 still refused to talk directly with the Vietnamese, held back any possible progress to resolve the problem. The first Sino-Vietnamese meeting (at the vice-ministerial level) in nine years took place in January 1989. It was not until September 1990 that both sides reached agreement with regards to Cambodia, mostly on Chinese terms. Both countries finally normalized relations in November 1991. By this time, Lê Duẩn (July 1986) and Lê Đức Thọ (October 1990) – the key architects of the Vietnamese invasion – had passed away, and a new generation of leaders had replaced them. Vӑn Tiến Dũng, who led the 1978 invasion and who was “the least inclined to cooperate with China,”Footnote 55 had retired. All these changes made it possible to convene the second International Conference on Cambodia in Paris in October 1991, which finally ended the conflict.

With hindsight, it is possible to view the Vietnamese invasion of Kampuchea (now Cambodia) as the start of the slow end of the Cold War in Southeast Asia. Nayan Chanda rightly pointed out that although the Vietnamese were victorious in 1978–9, it was to be a “hollow” victory, “literally and metaphorically.” In the words of one Vietnamese official, “in the end, this is our version of Afghanistan.”Footnote 56 Conversely, China, which had supported the Khmer Rouge, was the “ultimate winner,” as it managed to turn “defeat into victory.”Footnote 57 Cambodia is the strongest ally of China in Southeast Asia today. Vietnam, for its part, is still making up for lost time.