Life on our planet is more hazardous now than it has ever been. During the past few decades, trends in disastrous events, both natural and man-made, have risen in number and increased in intensity. Reference Wijkman and Timberlake1 During the past 10 years, 83% of all disasters were triggered by natural hazards, specifically climate change-related events such as floods, storms, and heat waves. 2 A sustained increase in the number of climate-induced disasters has taken place, with up to 335, approximately 14% higher than during the previous decade. 2,Reference Chen, Bagrodia and Pfeffer3 It is clear that climate change has added more uncertainty and severity to natural incidences in a way that they can adversely affect man-made disasters (hybrid disasters), such as nuclear power plant accidents, other industrial accidents, wars, and conflicts. Reference Dixon, Bullock and Adams4–Reference Akpan-Idiok8

Compared with natural hazards, human-induced and socio-technical hazards appear to be harder to foresee and more complex to identify, with arguments about their causes and consequences often being political and contentious with long-term effects. Reference Beck9,Reference Baum, Fleming and Davidson10 These hazards provoke a serious disruption of the economy, agriculture, and health system, typically producing long-lasting effects such as disrupting public health and other basic infrastructure services, causing famine and disease, and often killing more people indirectly than those who die from combat. This disruption perpetuates underdevelopment. Reference Harding11

Although disasters may appear to be nondiscriminatory in their effects, numerous examples of discrimination can be seen in the wake of a disaster. Reference March12 The burden of a disaster is influenced not only by hazard events but also by the exposure and vulnerability of populations. According to several studies, women, children, the elderly, the socio-economically disadvantaged, and forcibly displaced populations are the most vulnerable groups to hazards. Reference Waisel13,Reference Schwerdtle, Bowen and McMichael14

During the past decade, unprecedented amounts of forced migration have occurred across the globe, causing a growing humanitarian crisis. One spatial study showed that climate-related disasters affect forced displacements over short- to medium-distances. Reference Conigliani, Costantini and Finardi15 According to the available data, by the end of 2021, there were 89.3 million forcibly displaced people worldwide. This includes 53.2 million internally displaced persons (IDPs), 27.1 million who flee their home country by crossing international borders, called refugees, and 4.6 million asylum seekers. 16

These forcibly displaced populations, including IDPs, who move within their country’s borders or refugees moving across international borders, have specific vulnerabilities compared with the general population of local people and other types of migrants. Reference Harris, Minniss and Somerset17–19 They face many difficulties with acculturation, financial strain, disease, and health service use patterns that should be considered by the government to support them. Reference Siriwardhana and Stewart20

Besides all the numerous negative impacts of disasters on our built and natural environments, the health impacts of disasters must not be overlooked. Reference Alipour, Khankeh and Fekrazad21–Reference Field and Barros23 These health impacts vary from immediate impacts, such as injury and death, to longer-term impacts, such as nutritional problems, respiratory system disease, infectious disease, and mental health problems. Reference Banwell, Rutherford and Mackey24–Reference Sapir27 This inevitable relationship between disasters and human health is not straightforward.

Disaster-induced human displacement is associated with an increased risk of physical and mental health disorders. 28 Evidence shows worse mental health outcomes and poorer physical health among the displaced population compared with the nondisplaced population. Reference Jang, Ekyalongo and Kim29 Disasters not only affect refugees’ health, both physically and mentally, but continue to threaten their health in the host countries. In ensuring health equity for this particularly vulnerable group, the forcibly displaced populations’ higher needs for health services should be taken into consideration.

While numerous studies have focused either on disasters and migration or disasters and health, and a few defragmented studies are available on specific health problems within these populations, limited consideration has been given to the nexus between disasters, migration, and health. Reference Hendaus, Mourad and Younes30–Reference Fukushi, Nakamura and Itaki33 A clear picture of the overall health problems that disaster-induced displaced populations encounter is lacking. As far as we figured out, there was no comprehensive review to provide a deep understanding of the health impacts of disasters on neglected displaced populations, map the field, provide an analytical reinterpretation, and identify gaps. Therefore, this review intends to fill this gap by highlighting areas where research is lacking to adequately address the health needs of these vulnerable populations.

Our scoping review examines the important interaction among these three factors, focusing on adverse health impacts among populations with mid- to long-term disaster-induced displacement. It will provide a clearer picture of the overall health needs of these populations. Furthermore, it can help the host country's health-care system better meet the health needs of the displaced population and ultimately build up a more resilient society, considering the interactions between this population and the native population.

Methods

This scoping review follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist Reference Tricco, Lillie and Zarin34 in combination with the Arksey and O’Malley methodological framework. Reference Arksey and O’Malley35 Multiple joint sessions were undertaken to ensure that the research team members shared a common knowledge of research design and data extraction forms. Details of each stage in this study are mentioned below.

Step One – Identifying the Research Question and Eligibility Criteria

The purpose of this review is to answer the following research question: What are the health problems of people who have been forcibly displaced due to disasters?

Considering the unclear border between some definitions, authors used the most recent United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) 16 emergency handbook to clarify words such as “refugee,” “illegal/undocumented migrants,” “stateless person,” and “IDPs.”

The novelty of the topic and our broad research questions made us use the scoping review to map the literature, summarize the depth and breadth of the field, provide an analytical reinterpretation of, and identify the gaps in the existing literature in the past three decades. The time frame has been chosen because the UN General Assembly announced the 1990s as the International Decade for Natural Disaster Reduction due to the big increase in disasters compared with previous decades. Reference Coppola36 There was a feasibility concern about the nature of scoping review studies, specifically between being broad and comprehensive at the same time in the data extraction process. To overcome this, inclusion and exclusion criteria for studies are defined and used.

Step Two: Search Strategy and Identifying the Relevant Studies

A comprehensive search strategy was developed, covering central issues relevant to the study. The key concepts have been defined using the research title and question. First, M.M. ran some pilot searches to make sure what types of related terms and databases were appropriate for this study. The PubMed, Web of Sciences, and CINAHL databases were chosen for peer-reviewed scholarly as well as gray literature from most relevant organizations, such as the World Health Organization (WHO) and UNHCR. The final search key terms were divided into three groups: disasters, displaced populations, and health problems, for papers published between January 1990 and June 2022 (Table 1).

Table 1. Keywords and search terms employed in the database searches

During this process, the author noted that a few highly cited papers were excluded because they did not contain words pointing to a health problem in their titles. So, to reduce the likelihood of missing relevant articles, the search was run once again without “health-related problems” keywords to keep it as comprehensive as possible. Furthermore, after removing duplications, another 463 papers were imported to the search results. The final search resulted in 3264 studies. The search outputs were entered into the Web-based Covidence software for future analysis, and 282 papers were recognized as duplications and were removed. 37

Step Three: Selecting Studies Through Screening Process

This step is reflected in PRISMA-ScR (Figure 1). In the title and abstract screening step, all 3264 studies were independently checked following the eligibility criteria provided below to identify the relevant one by M.M. and M.E., and conflicts in this phase have been solved by H.J. During this step, a set of eligibility criteria has been developed to better determine the “best fit” studies. It included:

-

Inclusion criteria: Study types include all original peer-reviewed studies, commentary, reviews, and gray literature in the time frame between January 1990 and June 2022. The population of interest was first-generation refugees and IDPs who had long-term displacements, not just emergency evacuations, and studies that reported at least one health impact (physical or mental) of disasters on forcibly displaced populations.

-

Exclusion criteria: Studies disseminated in languages other than English and papers whose full text was not available or did not focus on a specific topic directly were not included in this study. Financial disasters were excluded, so the population does not include migrant workers or any other type of planned migration. Also, it was decided to exclude asylum seekers because their health situation and health service use in the host country can be massively different because their claim for refugee status has not been determined yet and they are not recognized as official clients for the health system.

Figure 1. Flowchart of the search strategy and results.

There were many irrelevant studies in this step, which reflects the complexity of the topic and terminology and the fact that the search result was broader than being deep. Conflicts in this phase have been solved by H.J.

This was followed by a full-text review to identify more relevant papers to the topic and research questions. The full content of the articles has been independently reviewed by 2 researchers (M.M. and H.J.) and 1 conflict solver (M.E.). The main reasons for excluding papers were wrong population, wrong indication, unavailability of full text, focus on intervention instead of health problems, full text being in another language other than English, and focusing on adaptation strategies. The outcome yields 48 studies, which are imported into the data extraction phase.

Step Four: Data Extraction

Data were extracted from eligible publication included in the review (48 studies) using standardize data extraction tool in Covidence. Two reviewers (M.M. and Y.D.) independently extracted the data. Extracted data were checked by H.J. by M.M. and Y.D., and the senior analytic M.M. resolved any conflict or disagreement in this phase. Extracted data include study title, author, year of published, study aims and objective, methods, participants, study location, types of displacements, county of displacement, destinated county for IDPs, duration of being a refugee, reasons for displacement, key findings, limitations, and authors conclusion (see Table 2).

Step Five: Data Analysis and Synthesis

Thematic and content analysis were applied to understand the breadth and depth of the issues. In the thematic and content analysis, authors applied the “narrative review” approach to identify themes and sub-themes, followed by a summative approach to qualitative content analysis starts with identifying and quantifying certain words or content in the text to understand the contextual use of the words or content to develop the health challenges in forcibly displaced people due to disasters worldwide.

Two main themes were identified for data synthesis: physical health and mental health. Then the extracted data were re-read to identify the subthemes (M.M). The identified subthemes for physical health include physical trauma and injuries, drug resistance, communicable diseases, noncommunicable diseases, environmental hazards, and health-related behavioral problems. The identified subthemes for mental health include premigration trauma, postmigration traumas, psychological impacts of discrimination, PTSD, depression, anxiety, loneliness, stress-related disorders, behavioral problems, psychosomatic complaints, worsened mental health conditions, and suicidal ideation/suicide. M.M., F.D., and Y.D. read the extracted data of the studies independently and gave the scores for each study. If the sub-theme is discussed in a particular study, authors were given 1 point, and if not, 0 points. Data synthesis was checked, and conflicts were resolved by discussion among three team members (M.M., F.D., and Y.D.). The data synthesis final results were tabulated and provided as supplementary material.

Results

Of 241 full-text scientific papers and 12 gray literatures screened, 48 documents were identified as fully relevant to this study. Figure 1 summarizes the screening process based on the PRISMA-ScR diagram.

Descriptive Results

The original research on health problems due to increasing disasters in forcibly displaced populations shows a growing body of literature. During 1994–2014, there were only six papers, but this increased 550% to 39 for 2015–2020. The majority of original studies focused on a single hazard, whereas most of the systematic review papers and gray literature discussed disasters that originated from multiple hazards in a specific region or country. Several types of disasters were discussed in the 48 included papers; however, most of the papers focused on war and conflict, nuclear incidents, and complex disasters (such as the combination of a natural hazard and armed conflict) at 45%, 21%, and 23%, respectively (see Table 3).

Table 2. Data extraction format for each paper

Table 3. Share of each disaster category in the included papers

Geographical Distribution of Studies

The geographical distribution of studies based on countries shows Japan with the highest number of papers—nine papers all on IDPs resulting from the Fukushima nuclear power plant incident. Reference Fukushi, Nakamura and Itaki33,Reference Nomura, Blangiardo and Tsubokura38–Reference Sawano, Nishikawa and Ozaki43 Next was the United States, with four papers on IDPs affected by Hurricane Katrina and war refugees from Ukraine, Belarus, Russia, and Germany. Reference Myles, Swenshon and Haase32,Reference Foster and Goldstein44–Reference McGuire, Gauthier and Anderson46 Australia and Jordan conducted three studies on both refugees and their psychological and occupational health. Reference Chen, Hall and Ling47–Reference Ziersch, Walsh and Due49 All other countries, with only 1 paper, were Greece, Sweden, Kosovo, Serbia, Israel, Lebanon, Pakistan, Indonesia, Nepal, Bangladesh, Sudan, and Ethiopia, which included both IDPs and refugees discussing different health problems in these populations (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Geographical distribution of included papers based on country.

Figure 3. Themes of results analysis.

Based on the available data on the regions, the largest number of published papers came from Asia (central, northeast, and southeast), followed by the Middle East, North America, and Europe. Australia and Africa occupied the last two places (Table 4).

Table 4. Geographical distribution of included papers with specified location based on regions

IDPs were the most researched populations, reported 15 times in total across all studies, compared with refugees 13 times in the review timeframe (Table 5).

Table 5. Home region and destination region for forcibly displaced populations of included papers

The majority of systematic review papers concentrate on the physical health impacts of disasters on settled populations in developed countries. Reference Maltezou, Theodoridou and Daikos50,Reference Lebano, Hamed and Bradby51

Thematic and Content Analysis

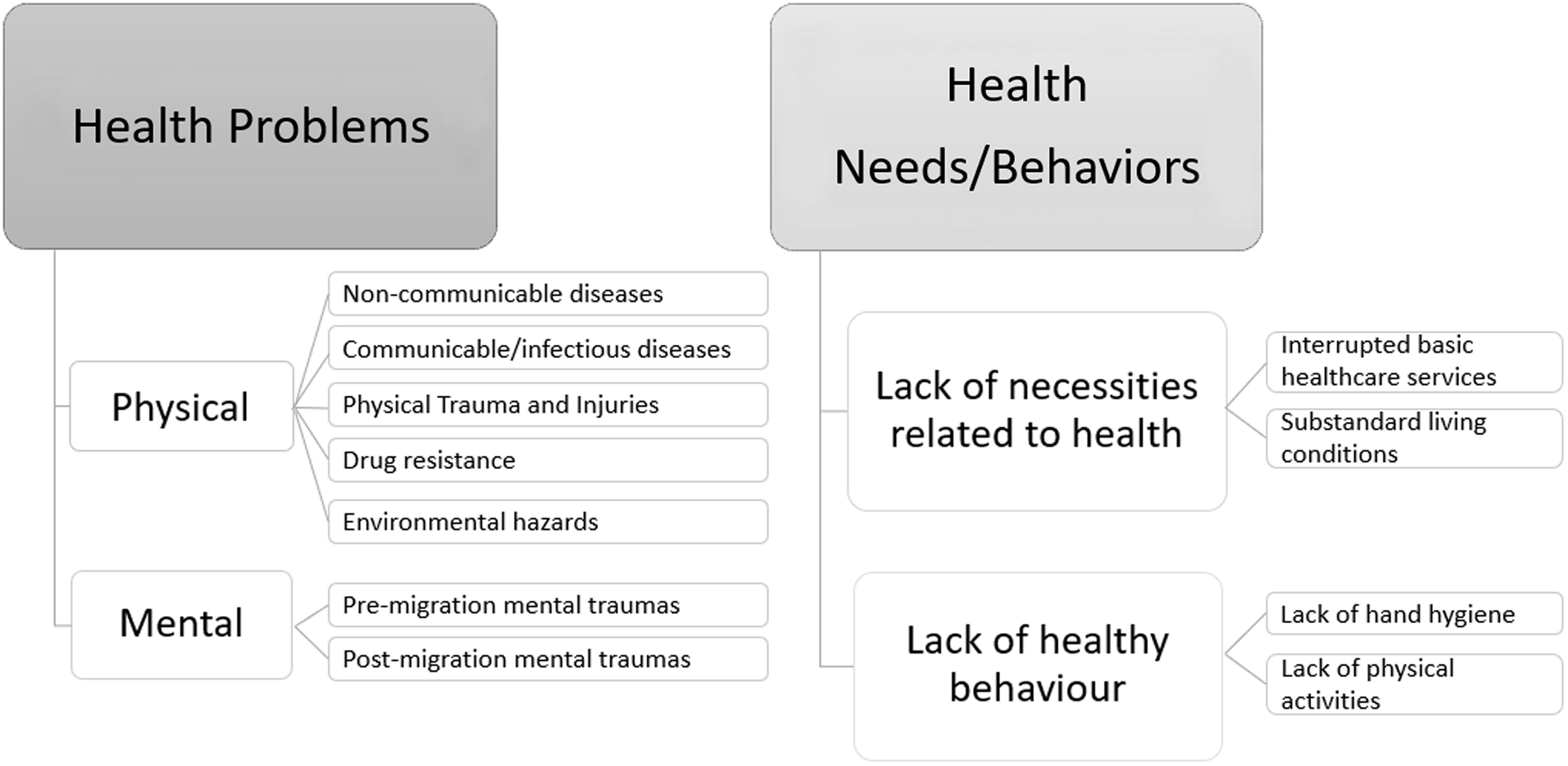

In the current study and response to our broad research question, researchers used the scoping review to map the literature, summarize the depth and breadth of the field, and create an analytical interpretation. Table 6 describes the main themes and sub-themes extracted from all of the 48 papers that were reviewed. The 4 main thematic categories included were “physical health impacts,” “mental health impacts,” “inadequate facilities and infrastructures,” and “lack of healthy behavior.” The numbers in the table show that some themes and subthemes appeared in multiple studies.

Table 6. The main themes and sub-themes extracted from included papers

Physical Health Problems

The findings of this study indicate physical health problems as the most discussed health problem among the displaced populations of the study—mentioned 91 times (see Figure 3).

Emerging new cases or worsened cases of noncommunicable diseases in the included studies consist of individuals who were more likely to have hypertension and hyperlipidemia, resulting in higher cardiovascular disease among IDPs impacted by the Fukushima nuclear accident. Reference Nomura, Blangiardo and Tsubokura38,Reference Hashimoto, Nagai and Ohira42 The other high-frequency drivers of noncommunicable disease was an unhealthy diet (malnutrition) among Syrian refugee children in Lebanon. Reference Chaya, Chalhoub and Jaafar52 Diabetes in Japan was in the next place. Reference Kuroda, Iwasa and Goto39 Afterward, the respiratory diseases were then discussed in a 20-y follow-up study on refugees from areas contaminated by the Chernobyl accident in the former Soviet Union, Reference Slusky, Cwikel and Quastel53 and substance abuse among Bhutanese refugees in Nepal. Reference Luitel, Jordans and Murphy54 Although the connection of these complications with previously mentioned hazards cannot be proven and it cannot be said that they are directly caused by the hazards, but these complications in the displaced population can be indirectly related to the hazards and challenges of displacement. Also, oral health conditions, occupational diseases, maternal and child health problems, and kidney disease Reference Lebano, Hamed and Bradby51 were described.

Compared with other communicable diseases, the COVID-19 pandemic, manifested as a global disaster, attracted more scholarly attention in developing countries. For example, studies on Rohingya refugees’ health situation in Myanmar and IDPs in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Bangladesh, and Yemen. Reference Pritchard, Collier and Mundenga55,Reference Patwary and Rodriguez-Morales56 Cholera prevalence among IDPs in South Sudan, malaria in Afghan refugees and IDPs in Pakistan, and TB control in the Syrian humanitarian crisis were discussed. Reference Peprah, Palmer and Rubin57–Reference Boyd and Cookson59 Intestinal parasites, meningitis, HIV/AIDS, dengue, diphtheria, and hepatitis have also been investigated, mostly in developing countries’ populations and IDPs. 28,Reference Li, Liddell and Nickerson60

Physical trauma and injuries were considered in a study undertaken 12 months after Hurricane Katrina that showed long-term displacement is associated with an increased risk of fractures in elderly individuals, Reference Uscher-Pines, Vernick and Curriero45 as well as literature on neurological disorders that accompany complex humanitarian emergencies and natural hazards. Reference Mateen61 The fourth subtheme extracted from a study on Syrian and African refugees settling in Europe was drug resistance. Reference Maltezou, Theodoridou and Daikos50

Environmental hazards, such as contaminated environmental factors (soil and water), were investigated. A qualitative study on young children as IDPs due to Haiti’s earthquake dealt with human feces and sharp objects in their public areas and nuclear radiation estimation using the oxidative stress marker urinary 8–hydroxy–2'–deoxyguanosine (8–OHdG). Reference Fukushi, Nakamura and Itaki33

Mental Health Problems

Mental health problems were considered the second main theme in this study, with 63 repetitions. It consists of two main subthemes: premigration migration traumas and postmigration traumas. A high percentage of Syrian refugees who were exposed to war scenes and who lost at least one family member before crossing the Lebanon borders experienced pre-migration traumas. Reference Hendaus, Mourad and Younes30 This was the same as a study on refugees from different countries in Middle East who faced traumatic events during their journey to Europe. Reference Arsenijević, Schillberg and Ponthieu62 While most studies concentrate on postdisaster mental health problems, the focus of many vary depending on location. Postmigration trauma studies mainly concentrate on PTSD or stress-related disorders in Middle East, South Asian, and African adult refugees, as well as refugee children’s psychological health in Australia. Reference Chen, Hall and Ling47,Reference Bryant, Edwards and Creamer48 Anxiety-related disorders were estimated to be high among long-term refugee populations in Europe and the United States, Reference Kien, Sommer and Faustmann63,Reference Bogic, Njoku and Priebe64 including post-Hurricane Katrina depression among IDPs, Reference McGuire, Gauthier and Anderson46 worsened mental health conditions and dementia (such as mental, behavioral, and neurodevelopmental disorders) in older populations. Reference Massey, Smith and Roberts65 An immediate increase in the rate of suicidal ideation/ suicide in evacuation areas compared with non-evacuees in Fukushima Prefecture, Japan, has been observed. Reference Orui, Suzuki and Maeda40 Loneliness, Reference Chen, Hall and Ling47 psychological impacts of discrimination on temporary refugee visa participants who experienced some discrimination in the Australian labor market, Reference Ziersch, Walsh and Due49 behavioral problems, psychosomatic complaints, Reference Kien, Sommer and Faustmann63 and violence Reference Patwary and Rodriguez-Morales56 have also been discussed.

Lack of Basic Necessities Related to Health

Interrupted basic health-care services and substandard living conditions caused by COVID-19 for people in overcrowded refugee camps who could not follow the physical distancing, self-isolation, and vaccination requirements, as well as not having enough access to adequate washing facilities and insufficient medical equipment and health-care workers. Reference Patwary and Rodriguez-Morales56,Reference Ahmad, Ahmad and Sadia58,Reference Nott66

Lack of Healthy Behavior

Displacement fosters a lack of healthy behaviors like insufficient hand hygiene and physical activity Reference Foster and Goldstein44,Reference Medgyesi, Brogan and Sewell67 as well as smoking and substance abuse.

Discussion

Disasters, whether natural, climate-related, or human-induced, adversely affect human physical and mental health, leading to significant morbidity and mortality in the involved populations. Reference Ebi, Vanos and Baldwin68,Reference Mazhin, Khankeh and Farrokhi69 Our review study explored the disasters’ long-term health impacts on forcibly displaced populations. In this review, the highest number of studies were conducted in Japan, a developed country with IDPs, while the biggest number of displaced populations who cross international borders are from developing countries to developed countries with few or no studies. This could be explained by Japan’s exposure to several severe disasters during the past 2 decades, as well as the country’s disaster management strategy. Reference Mavrodieva and Shaw70

Our results demonstrate that approximately 89% of the included studies addressed human-induced disasters. This shows that human-induced hazards have caused more vulnerability due to displacement and, accordingly, more health problems. In addition, in 2022, more than 6.3 million refugees left Ukraine for surrounding countries between February 24 and May 17. 71 This increasing number of displaced populations all around the world threatens people’s health through fundamental infrastructure destruction, food scarcity and starvation, and an increased risk of communicable diseases, injuries, and deaths. Reference Mugabe, Gudo and Inlamea72,Reference Hotez and Gurwith73

Disasters adversely impact the health of people in different ways. Our significant findings were described clearly as four major themes: people’s physical and mental health, lack of necessities related to health, and lack of healthy behavior. Other studies have also shown that forcibly displaced migrants face a triple burden of noncommunicable diseases, infectious diseases, and nonbehavioral health issues due to their condition. Reference Abbas, Aloudat and Bartolomei74 Also based on syndemic theory, the synergistic nature of stressors, chronic diseases, and environmental impacts on immigrant and refugee populations living in vulnerable conditions, we should consider the immigrant experience, including migration pathways, poverty, cultural distance, and a lack of social support. Reference Ofosu, Luig and Chiu75

In addition, refugees are a population with unique psychosocial challenges, sets of chronic noncommunicable diseases, and needs for various public health measures. Most of them have left behind or lost their relatives, friends, and colleagues. Most have lost their homes, properties, jobs, and schools and appeared in culturally and linguistically distinct situations. Their adaptation to the new environments largely depends on humanitarian support, rehabilitation, and care. Reference Zimba and Gasparyan76

Physical Health Problems

Regarding the effect of disasters on physical health (91 cases), the worsening of noncommunicable diseases (45) was the highest, followed by communicable (infectious) diseases (30). Among the noncommunicable diseases, cardiovascular diseases and nutrition-related health issues were the most identified in the literature. Noncommunicable diseases can be attributed to several causes. The forced displacements increase health risks, especially for vulnerable groups, including the elderly and those who have already been suffering from other diseases. Additionally, the sudden intense activity by formerly sedentary people, the “fight or flight” physiological response to danger, and the interruption of treatment for other medical conditions may result in or worsen the already existing health problems, especially cardiovascular diseases. Reference Mazhin, Khankeh and Farrokhi69,Reference March77 Similarly, the increased stress load during disasters significantly impacts these diseases. Nutrition-related health issues can be explained by the low quantity and quality of the food provided to refugees in their camps. Malnutrition critically affects children’s health, resulting in underweight, stunting of growth, and micronutrient deficiencies. Reference Fabio78–Reference Yaghi80 Rabkin et al. Reference Rabkin, Fouad and El-Sadr81 also concluded that forced migration caused by conflicts causes higher levels of chronic disease in the population.

Factors associated with communicable (infectious) diseases include, are not limited to, settings where there is a prevalence of poverty, overcrowding, poor sanitation, highly vulnerable individuals, restricted access to health care, impaired health system, and limited public health services and infrastructure. Reference Pritchard, Collier and Mundenga55,Reference Mateen61

In addition, malnutrition and a lack of immunization and access to sanitation and potable water exaggerated the exposure and potential for infection among IDPs and refugee children. Reference Murray79 The increased risk that refugees and asylum seekers have for infection with specific diseases can largely be attributed to poor living conditions during and after migration, as most asylum seekers arrive at their destination after a period in transit and have been subject to poor living conditions and changing disease epidemiology. Reference Eiset and Wejse82

Moreover, a high prevalence of neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) has been documented in populations displaced by conflict because NTDs generally affect the least advantaged people in poor societies, and already susceptible people become even more vulnerable when forced from their communities as IDPs, refugees, or forced migrants. Reference Errecaborde, Stauffer and Cetron83

Mental Health Problems

In our review study, the impact of disasters on mental health was identified in 63 cases. Results suggest that postmigration traumas had a much greater prevalence than premigration traumas. All these traumas can cause situations that may adversely affect the mental health of those who are direct witnesses to or directly affected by the disasters, as well as the family members and co-workers of the deceased victims. Reference Naushad, Bierens and Nishan84 The traumatizing potential of human-induced disasters appears to be greater than that of natural ones. Reference Myles, Swenshon and Haase32 Furthermore, ongoing or displacement-related stressors in the host country have an additional negative impact on the mental health of refugees and asylum seekers. Reference Miller and Rasmussen85 PTSD was the most frequently encountered problem (12 cases). Similarly, PTSD, one of the stress-related disorders, was described as the most common psychological disease after a disaster. Reference North, Nixon and Shariat86,Reference Wahab, Yong and Chieng87 Murray Reference Murray79 addressed displaced refugees’ children who could be affected by PTSD due to an extended length of nightmares, sorrowful reactions, negligence, social withdrawal, psychological stress, and interrupted sleep. A considerable rise in stress levels was identified in IDPs living in temporary housing following the complex disaster resulting from the earthquake and tsunami that led to the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant accident (FDNPP accident); these levels are positively correlated to the length of time living in temporary housing. Reference Fukushi, Nakamura and Itaki33

Based on studies of many refugee children who witnessed destruction, violence, displacement, and forced separation from their relatives, they have been profoundly affected by PTSD, depression, anxiety, and other emotional and behavioral reactions. Importantly, children in host countries who witness refugees’ painful sufferings have developed peritraumatic dissociative symptoms and anxiety. Reference Maftei and Dănilă88

Overall, providing support by accompanying family members can reduce refugees’ stress levels. However, psychological distress presenting as sleep disorders, nightmares, anxiety attacks, mutism, and depression would require more serious attention from parents and caregivers and psychological interventions. Some of the expert-recommended group interventions have include dance and art therapies for children accommodated in a safe environment, free from any noise triggers. Reference Izuakor and Nnedum89

Health Needs and Behaviors

The impact of disasters on health needs and health services was addressed in 14 studies. Disasters have been linked to humanitarian crises and enormous public health challenges, especially in low-income countries. Reference Donev, Onceva and Cligorov90 Hence, it is critical to provide the affected people with adequate potable water and sanitation facilities as crucial components of essential health services. Reference Mugabe, Gudo and Inlamea72,Reference Marwat, Ronis and Sanauddin91 This has been reflected in the study by Hendaus et al. Reference Hendaus, Mourad and Younes30 that found unequal access to health services between migrants and nonmigrants, particularly regarding mental and dental health.

Finally, a qualitative study of 36 public areas in Haiti’s earthquake IDP camps quantified the exposure of young children to unsafe and unhealthy residential sites that can contribute to illness and injury. Reference Medgyesi, Brogan and Sewell67 Similarly, Chung et al. Reference Chung, Harada and Igari41 found a significant association between post Fukushima IDPs’ lifestyles and the incidence of diabetes. Central to these settings are unhealthy behaviors, such as poor dietary choices, lack of physical activity, and stress due to displacement: all factors that have been associated with increasing the risk of diabetes.

Additionally, forced migrants may be at risk for substance abuse as coping mechanisms for traumatic experiences, co-morbid mental health disorders, acculturation challenges, and social and economic inequality. One in 3 forced migrants may be using alcohol in harmful or hazardous ways, and, when measured among current drinkers only, this estimate may be as high as 2 in 3. Reference Horyniak, Melo and Farrell92

The most important limitation of the study is the time period. Due to the extensiveness of the work, we did not include studies before the year 2000 in the study. The next limitation of this review was not addressing the health problems of planned immigrations due to natural and technological disasters. Another limitation of this study was the vagueness in the definition of disasters, which made it impossible to easily identify the effects of disasters on displaced populations. For this purpose, we used 2 independent authors in all stages of the study review and included more studies in the full-text review phase. This review only addressed the health problems of forcibly displaced people in the mid- to long-term time frame after disasters. It was not possible to make sure that all the health problems stated in the included studies were uniquely due to forced displacements and did not neglect other factors, such as ethnicity. Given this study is based on published literature, it can only reflect part of what is experienced “in the field” with many aspects of reality not covered here.

Conclusions

This study reviewed the published evidence on the health problems in disaster-impacted populations with a focus on adverse health impacts among populations that experienced mid- to long-term displacement. While fully recognizing the great diversity and complexity of displaced populations, contexts, health needs, and health outcomes, this scoping review does provide some reliable findings, highlighting key health problems and other adverse health outcomes among displaced people potentially associated with displacement due to disasters.

These findings can help the host countries’ health systems better meet the health needs of the displaced population and, ultimately, build a more resilient society by on-time response to health problems of forcibly displaced population, ensuring their access to health services and helping them returning to Their routine lives. Most referenced physical health problems, including noncommunicable diseases, respiratory diseases, and nutrition-related issues. Mental health problems were the second main theme, covering premigration and postmigration traumas, anxiety-related disorders, and psychological impacts. Lack of basic necessities related to health and lack of healthy behavior were also identified as important themes.

To date, and based on this review, it seems important that research and policy related to migration also considers the links among disasters, health, and migration as determinants of health in the new era of forced displacement, including climate change-driven displacements.

Given the diverse health impacts that arise in the context of disasters, responsive policies and approaches are required that address the vulnerabilities of communities at risk of, or involved in, forced migration, while supporting the adaptive potential of health outcome responses. The degree to which climate data are meaningfully integrated into health system resilience research exploring migration and health in the context of a changing climate warrants further consideration and analysis to maintain quality in this emerging nexus of research.

Governments and international organizations should create thorough plans for disaster response that pay special attention to the health requirements of forcibly relocated people. These plans should take into account a variety of threat exposures from such complex disasters. They should concentrate on making sure that displaced populations have access to health-care services, including support for their physical and mental health needs, both during and after disasters. Furthermore, it is essential to increase international cooperation between governments, humanitarian organizations, and research institutions due to the global dimension of the difficulties encountered by displaced populations. Collaboration can aid in the creation of uniform policies and procedures for attending to the medical requirements of displaced populations in various geographical locations.

Moreover, governments and humanitarian organizations should allocate enough funds to provide displaced populations the basic health services they need. This entails making sure that everyone has access to primary health care, mental health services, and specialized services for treating infectious diseases, noncommunicable diseases, and injuries brought on by trauma. Additionally, funds should be put aside to upgrade the infrastructure and facilities for health care in displaced areas like refugee camps.

To address the trauma, stress, and other mental health issues faced by those who have been displaced, governments and humanitarian organizations should invest in mental health services, such as screening, counselling, and therapy both in the immediate displacement and after settlement. To guarantee continuity of treatment for those who have been displaced, governments should take the long-term viability of health-care services into consideration.