1. Introduction

What is grammatical gender? How is it acquired and how does it change in situations of language contact or reduced input and use? Finally, what can studies on the acquisition and attrition/change of gender tell us about this somewhat mysterious linguistic category? In this paper, we discuss recent research on acquisition and change of grammatical gender, with a focus on Norwegian varieties, and we make an attempt at tackling these fundamental questions.

Grammatical gender is acquired relatively late in Norwegian, due to the nontransparency of gender assignment (Rodina & Westergaard 2013). A surprising finding in recent years is that feminine gender appears to be in the process of being lost in many dialects of Norwegian, including areas where the traditional three-gender system has been assumed to be quite stable in the spoken language, such as Tromsø (Rodina & Westergaard 2015) and Trondheim (Busterud et al. Reference Busterud, Lohndal, Rodina and Westergaard2019). Studies of Scandinavian heritage languages also show that the grammatical gender system is somewhat vulnerable in these populations (Heegård Petersen & Kühl Reference Heegård Petersen and Kühl2017 for Heritage Danish, Johannessen & Larsson 2015 and Lohndal & Westergaard 2016 for Heritage Norwegian). In the acquisition of gender in mono- and bilingual children, it is clear that there are some forms expressing gender distinctions that are in place much earlier than others. For example, the definite suffix is acquired several years before the indefinite article (see, among others, Rodina & Westergaard 2013). A similar pattern between bound suffixes and free-standing forms is found in attrition and change, where certain forms are more vulnerable than others.

In our view, a key to understanding the gender category lies in identifying the cues that children are sensitive to in the acquisition process. In turn, these cues should create the foundation for a formal theory of grammatical gender. This paper argues that data from acquisition and attrition/change can inform such a formal theory. Certain morphosyntactic forms are stable across speakers and populations, whereas others are vulnerable and subject to change. We discuss why that is and what this says about the nature of grammatical gender.

The structure of the paper is as follows: In section 2, we discuss the organization of grammatical gender systems in Norwegian, and in section 3 we outline our theoretical assumptions and formulate the research questions. Section 4 provides an overview of grammatical gender in contexts of acquisition, attrition, and dialect change. Section 5 outlines a formal analysis, and section 6 is a brief conclusion.

2. Grammatical Gender Systems in Norwegian

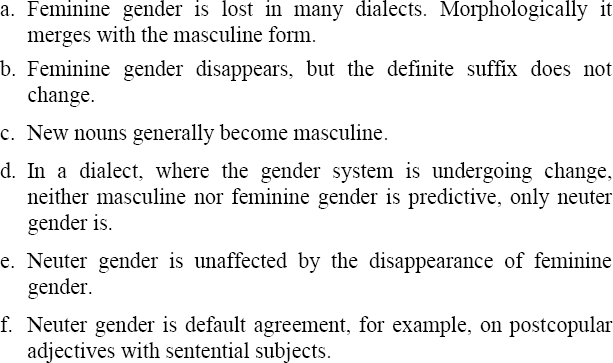

Norway is a country rife with dialectal variation (Haugen Reference Haugen1976, Vikør Reference Vikør1995): Every village essentially has its own dialect, and people mostly use their dialect in every aspect of life, making communication “polylectal” (Røyneland Reference Røyneland2009:7). Traditionally, the three-gender system (masculine, feminine, neuter) has been preserved “in the overwhelming majority of the Scandinavian dialects down to the present” (Haugen Reference Haugen1976:288; setting aside the Bergen dialect as a well-known exception with a two-gender system of neuter and common (masculine + feminine) gender; see Jahr 1998, Reference Jahr2001 and Nesse Reference Nesse2005). The following table illustrates the ways in which gender is typically expressed in many dialects (excluding pronouns). Gender agreement is only expressed in the singular, but we also provide the plural indefinite and definite suffixes here.

Table 1. The traditional gender system in many varieties of Norwegian (idealized version based on a three-gender dialect).

There is considerable syncretism between masculine and feminine, for example, in the adjectives (setting aside the exceptional adjective meaning ‘little’, which distinguishes all three genders, liten (m)–lita (f)–lite (n)). Norwegian also displays double definiteness, which involves marking definiteness both with a suffix on the noun itself and on a prenominal determiner in contexts where the noun is preceded by a demonstrative or modified, for example, by an adjective. In this case, there is also syncretism between the masculine and the feminine for the prenominal markers, with den being the common form and det being the neuter. The same applies to demonstratives and certain quantifiers, not illustrated in the table: denne bilen (m) ‘this car’, denne boka (f) ‘this book’, and dette huset (n) ‘this house’ for demonstratives, and all maten (m) ‘all the food’, all suppa (f) ‘all the soup’, alt rotet (n) ‘all the mess’ for quantifiers.

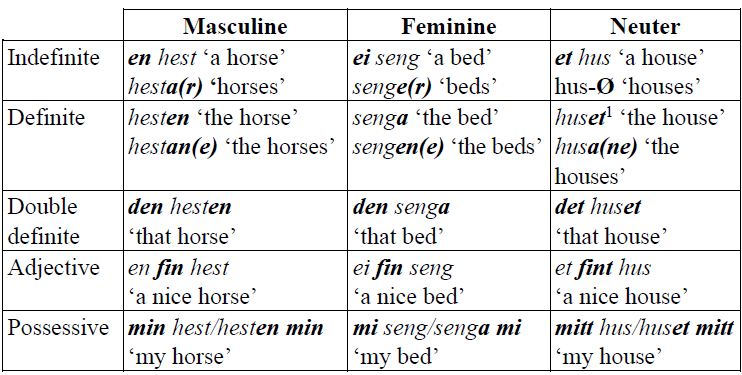

Some traditional Norwegian dialects have a system whereby each gender has two different definite suffixes. Table 2 provides a typical example from the dialect of Oppdal (Haugen Reference Haugen1982:69–78).

Table 2. Examples of inflectional forms in the dialect of Oppdal.

As the table shows, each of the three genders can be divided into two classes, often labeled strong and weak in the Germanic literature. There is also syncretism across some of the classes, for example, the strong feminines and the weak neuters have the same ending in the Oppdal dialect. It should be noted that table 2 is grossly simplified, as there are far more subclasses for each of the three genders if all patterns in the Oppdal dialect are taken into consideration (see Haugen Reference Haugen1982). There is also considerable variation in the morphosyntactic realization of gender and declension class across Norwegian dialects, as demonstrated in great detail by Skjekkeland (Reference Skjekkeland1997), but which we cannot cover here.

The classes in table 2 are often referred to as declension classes or inflection classes. These are often defined as groups of lexemes sharing a set of “inflectionally realised morphosyntactic properties” and “the inflectional markers” that realize them (Carstairs-McCarthy Reference Carstairs-McCarthy, Geert, Lehmann and Mugdan2000:630). As Aronoff (Reference Aronoff1994:66) puts it, an inflection class is “a set of lexemes whose members each select the same set of inflectional morphemes.” Further discussion of the relationship between declension class and gender may be found in Alexiadou Reference Alexiadou, Müller, Gunkel and Zifonun2004 and Vadella Reference Vadella2016.

Gender assignment in Norwegian is relatively nontransparent, in that there are very few, if any, reliable gender cues on the noun itself, unlike, for example, in Russian or Italian, where the morphophonological shape of a noun generally predicts its gender. Nevertheless, Trosterud (Reference Trosterud2001) has proposed as many as 43 different rules for gender assignment in Norwegian, comprising phonological, morphological, and semantic rules, as well as a masculine default. Unfortunately, most of these rules have a considerable number of exceptions, and some are quite specific (for example, words denoting buildings that are not used as permanent housing for humans are neuter), and it seems somewhat unlikely that learners of the language would acquire such rules or (semi-)regularities from input only. In an experiment using nonce words, Gagliardi (Reference Gagliardi2012) also shows that Norwegian children are not sensitive to the two cues argued to be the most reliable ones in Norwegian, the ending -e and reference to a female individual, both typical of feminine nouns, as in ei skjorte ‘a shirt’, ei søster ‘a sister’. This does not necessarily mean that gender assignment in Norwegian is completely arbitrary. For example, Bobrova (Reference Bobrova2013) shows that Norwegian adults relatively reliably distinguish between neuter and common (masculine + feminine) gender based on the animacy of a nonce word. However, what one ideally would like to see is how speakers perform on a set of nonce words that all refer to inanimates. This is investigated in ongoing work (Urek et al. 2018), and the findings suggest that there may be certain phonological patterns that adult speakers of Norwegian are (somewhat) sensitive to.

In a non-transparent system, frequency is important, and there is a considerable difference between the three genders in this respect, with the masculine being by far the most frequent gender. Based on the 31,500 nouns in the Nynorsk Dictionary, Trosterud (Reference Trosterud2001) has found that 52% of all nouns are masculine, 32% are feminine, and only 16% are neuter. In everyday use, the masculine is even more frequent: Rodina & Westergaard (2015) investigated samples of child-directed speech and found that token frequencies of masculine nouns make up as much as 62.6% of the input, while feminine and neuter nouns account for 18.9% and 18.5%, respectively.

Ongoing work suggests that there may be semantic as well as phonological cues or tendencies for gender assignment in Norwegian that speakers are to some extent sensitive to (Urek et al. 2018). For example, in a reading-based elicitation experiment where Norwegian native speakers had to read out nonce nouns and add an appropriate indefinite article, Urek et al. (2018) find that, although the masculine is clearly favored in all contexts, there is a statistically significant effect of certain final segments, with /-e/ often being linked to feminine gender and /-v/ to neuter. When the same nonce words are presented in an experiment with pictures (of novel inanimate objects), all participants produce exclusively masculine, suggesting that either semantics or the explicit instruction to add a gendered article may also play a role. However, further experiments are needed to better understand to what extent gender assignment in Norwegian is arbitrary or not.

Finally, we would like to mention gender assignment to loan words: Graedler (Reference Graedler1998) and Johansson & Graedler (Reference Johansson and Graedler2002) consider gender assignment to English borrowings in contemporary Norwegian based on corpus data. They find that 80–90% of the nouns are masculine, 10–20% are neuter, and very few are feminine (Johansson & Graedler Reference Johansson and Graedler2002:183). A considerable number of loanwords also fluctuate between masculine and neuter. Nevertheless, there are tendencies for certain endings on English nouns to correspond to a specific gender. For example, English loan words ending in -ing or -er are typically masculine in Norwegian, whereas monosyllabic nouns are typically neuter.

3. Theoretical Assumptions and Research Questions

The previous section illustrates the complexity of the Norwegian gender and nominal declension system. In this section, we discuss some relevant theoretical proposals and issues concerning grammatical gender and declension class before we present our research questions for this paper.

In the study of grammatical gender in Norwegian, a notoriously contested issue revolves around the definite suffix. This morpheme typically differs across the three genders, which has led scholars to analyze it as a real gender marker. For example, traditional Norwegian grammars (such as Faarlund et al. Reference Faarlund, Lie and Vannebo1997) consider the definite suffix to be an exponent of gender (see also Andersson Reference Andersson, Unterbeck, Rissanen, Nevalainen and Saari2000 and Dahl Reference Dahl, Unterbeck, Rissanen, Nevalainen and Saari2000 for a similar conclusion for Swedish). On the other hand, applying the definition given by Hockett (Reference Hockett1958), which states that “[g]enders are classes of nouns reflected in the behavior of associated words” (see also Corbett Reference Corbett1991), this suffix should not be considered to be an exponent of gender, but rather a declension class marker, as argued in Fretheim 1985, Lødrup Reference Lødrup2011, Rodina & Westergaard 2015, Lohndal & Westergaard 2016, Svenonius Reference Svenonius, Gribanova and Stephanie2017, and Busterud et al. Reference Busterud, Lohndal, Rodina and Westergaard2019. An in-between position is pursued by Enger (Reference Enger2004a:137), who argues that the suffix encodes gender to a certain degree (see also Berg Reference Berg, Fabrizio and Cennamo2019). Whether or not the definite suffix is an expression of gender or declension class also depends on what the relationship between gender and declension is in varieties of Norwegian, that is, whether gender can predict declension class or vice versa (see, in particular, Enger Reference Enger2004a).

From a crosslinguistic point of view, there is wide agreement that gender and declension class are distinct phenomena (see, among others, Roca Reference Roca1989; Harris Reference Harris1991, Reference Harris and Zagona1996; Halle Reference Halle, Booij and van Marl1992; Aronoff Reference Aronoff1994; Comrie Reference Comrie1999; Thornton 2001; Wechsler & Zlatić 2003; Alexiadou Reference Alexiadou, Müller, Gunkel and Zifonun2004; Kramer Reference Kramer2015; Svenonius Reference Svenonius, Gribanova and Stephanie2017). Formal approaches have developed different ways of capturing this distinction. For reasons of space, we only illustrate one approach here (see Kramer Reference Kramer2016 for an overview), which is couched within the theory of Distributed Morphology (DM). This approach argues that word formation consists of category-less roots that have to merge with elements of the functional vocabulary in order to form larger units (Marantz Reference Marantz1997; Alexiadou Reference Alexiadou2001; Arad Reference Arad2003, Reference Arad2005; Embick & Marantz 2008; Embick Reference Embick2015; De Belder Reference De Belder2011; Alexiadou & Lohndal 2017). For example, a root merges with a v to form a verb, and similarly, a root merges with an n to form a noun, as illustrated in 1.

(1)

A root has to be merged to ensure that a category is assigned, which Embick & Marantz (2008:6) label the categorization requirement. Kramer (Reference Kramer2015) argues that n is the locus of gender assignment, and she develops a comprehensive approach to gender within DM.

Next, let us consider how to account for declension class, given its importance for the analysis of grammatical gender in Norwegian. It is typically argued that declension class features play no role in syntax (see, among others, Harris Reference Harris1991, Reference Harris and Zagona1996; Aronoff Reference Aronoff1994; Oltra-Massuet Reference Oltra-Massuet1999; Alexiadou Reference Alexiadou, Müller, Gunkel and Zifonun2004; Embick & Halle 2005; Oltra-Massuet & Arregi 2005; Alexiadou & Müller 2008; Kramer Reference Kramer2015). This means that declension class features do not take part in syntactic operations such as, for example, agreement. For this reason, much work within the framework of DM argues that declension class information is inserted after syntax proper, in what DM labels the morphological component; that is, postsyntactically (see, among others, Embick & Halle 2005, Kihm Reference Kihm, Cinque and Richard2005, Halle & Matushansky 2006, Steriopolo Reference Steriopolo2008, Embick Reference Embick2010, Alexiadou Reference Alexiadou, Tsoulas, Hicks and Galani2011, Kramer Reference Kramer2015, Vadella Reference Vadella2016; see also Svenonius Reference Svenonius, Gribanova and Stephanie2017 for a somewhat different theoretical approach to some of the Norwegian data).

Space prevents us from going into the technical implementation in detail, but Kramer (Reference Kramer2015) argues that the declension class feature adjoins to the categorizing head, which is to say that 2a turns into 2b in the postsyntactic component (Vadella Reference Vadella2016, pace Alexiadou & Müller 2008).

(2)

Kramer (Reference Kramer2015:239) argues that for Spanish, this approach would require that roots are specified for which declension class they take. Kramer (Reference Kramer2015:238–239) discusses various ways in which this can be achieved technically, which in part depends on whether or not roots are allowed to carry declension class features. Since this is not important for present purposes, we set the specific choice of implementation aside here.

Given the empirical and theoretical landscape discussed above, several questions emerge, and in this paper we discuss the following:

(i) How is grammatical gender acquired across varieties of Norwegian?

(ii) How does grammatical gender change in Norwegian heritage language?

(iii) How does grammatical gender change across varieties of Norwegian?

(iv) How can one formalize grammatical gender in varieties of Norwegian and how could a formal model account for the answers to research questions i–iii?

Section 4 provides answers to questions i–iii, whereas section 5 outlines a formal analysis based on DM. This analysis captures the observed generalizations regarding grammatical gender in Norwegian, including the distinction between grammatical gender and declension class.

4. Gender Systems in Development: Stable Versus Vulnerable Cues

In this section, we address questions i–iii by providing a synopsis of recent studies on grammatical gender in Norwegian. Space does not allow us to go into great detail for each of the studies mentioned; rather, we attempt to summarize and extract generalizations across the following three domains: Acquisition, attrition, and dialect change.

4.1. Acquisition

Given the non-transparent nature of grammatical gender in Norwegian, one might expect delayed acquisition compared to other languages with more predictable gender assignment. Indeed, this turns out to be the case: Rodina & Westergaard (2015) provide experimental evidence that target-consistent gender assignment (of neuter gender) is not in place until approximately age 7 (with 90% accuracy). This is considerably later than in languages with more transparent gender assignment, for example, Russian or Italian (Kupisch et al. 2002, Rodina Reference Rodina2008).

The nontarget-consistent production attested in child data generally involves overgeneralization of masculine gender, argued to be the default in Norwegian and clearly the most frequently occurring gender in children’s input (see section 2). Occasional examples of this overuse of the masculine, affecting both feminine and neuter gender, are provided in Plunkett & Strömquist 1992 and Anderssen Reference Anderssen2006. A more systematic analysis is found in Rodina & Westergaard 2013, where corpora of two monolingual and two bilingual Norwegian-English children (Anderssen Reference Anderssen2006, Bentzen Reference Bentzen2000) were investigated. Their findings show that, although there is some variation across the four children and also across the different gender forms (for example, determiners, adjectives, and possessives), both the feminine and the neuter gender are affected to a considerable extent: For example, the feminine and neuter indefinite articles ei and et are replaced by the masculine form en 63% (69/109) and 71% (89/126) of the time, respectively, as illustrated in 3. Masculine gender, in contrast, is generally unproblematic, with only 1% nontarget forms (2/272).Footnote 2

(3)

These results differ from findings in languages with more transparent gender, where young children are found to overgeneralize a specific assignment rule rather than resorting to the default. For example, Russian children overgeneralize feminine gender to exceptional masculine nouns ending in -a, which is a typical feminine ending belonging to declension II (see, among others, Rodina & Westergaard 2012).Footnote 3

(4)

One consistent finding in the literature on the acquisition of Norwegian noun phrases is that there is a clear distinction between the definite and plural suffixes on the one hand and forms that show gender agreement with the noun on the other (the latter being true exponents of gender, according to Hockett’s Reference Hockett1958 definition). In Rodina & Westergaard’s (2013) study mentioned above, the findings based on the corpus data of the four children show that, while gender marking on determiners, adjectives, and possessives is highly problematic, the definite and plural suffixes are generally in place with the target-consistent form from early on: For the definite suffix, for example, the overgeneralization of the masculine -en ending to feminine and neuter nouns is only 4% for both genders (3/138 and 10/229, respectively).Footnote 4 This is in stark contrast to the nontarget-consistent production of gender forms on other targets, as illustrated for the indefinite article in 3 (63% and 71%). Similar findings are attested in experimental work (see, for instance, Rodina & Westergaard 2015, 2017 and Busterud et al. Reference Busterud, Lohndal, Rodina and Westergaard2019).

4.2. Attrition

In recent years, there has been some focus on Scandinavian languages as heritage languages, especially in North America. A heritage language is a language that is “spoken at home or otherwise readily available to young children, and crucially this language is not a dominant language of the larger (national) society” (Rothman Reference Rothman2009:156). Heritage speakers are simultaneous or successive bilinguals, and they often undergo a dominance shift around the age when they start school, from being dominant in the heritage language to becoming dominant in the majority language. In this process, their L1 may attrite as a result of reduced input and use, and, consequently, the language of adult heritage speakers is often somewhat different from the nonheritage variety (or the input that they received as children).Footnote 5

Grammatical gender in Norwegian heritage language in the USA and Canada has been investigated by a number of scholars, most notably Johannessen & Larson (2015) and Lohndal & Westergaard (2016). While they to some extent study the same data (the CANS corpus of elderly speakers who are mainly 3rd generation immigrants; Johannessen Reference Johannessen and Megyesi2015), they come to somewhat different conclusions: While Johannessen & Larsson (2015) claim that the gender system is relatively stable, Lohndal & Westergaard (2016) argue that grammatical gender is vulnerable. Coming back to the issue of definition raised in section 3, this discrepancy can mainly be explained as a result of different views on the definition of gender: While Johannessen & Larson (2015) follow the tradition in the study of Norwegian grammar, where the suffixes are considered to be gender markers, Lohndal & Westergaard (2016) assume the standard definition of gender in Hockett Reference Hockett1958 and Corbett Reference Corbett1991.

The reason why the choice of definition makes such a difference is that it determines the interpretation of the findings, which are essentially the same in both studies and correspond to what is found in child language data (see section 4.1): Most of the heritage speakers produce a high number of gender forms that deviate from the nonheritage variety. For example, according to Lohndal & Westergaard (2016), who studied 50 speakers in the CANS corpus, masculine gender is overgeneralized to feminine nouns 39% (92/236) and to neuter nouns as often as 48.8% (80/164) of the time. Examples are shown in 5: The masculine indefinite article is used with a feminine and a neuter noun in 5a and 5b, respectively. Crucially, however, the definite suffixes are virtually always retained with the baseline form.

(5)

Now, assuming that the definite suffix is an exponent of gender (see Johannessen & Larsson 2015), the data in 5 indicate that the gender system itself is intact. In contrast, assuming that the definite suffix only marks declension class (see Lohndal & Westergaard 2016), the conclusion is drawn based on the use of the indefinite article alone, and the same data suggest that gender is highly affected by attrition.

At first glance, Johannessen & Larsson’s analysis should be preferred: Most of the heritage speakers have an intact gender system, in that they use all three gender forms; they simply do not use them with the right nouns. That is, it is gender assignment that is vulnerable, which is not surprising given the non-transparency of the system. Furthermore, no speakers have a reduced gender system (of two genders instead of three), which has been attested for Russian heritage language (Polinsky Reference Polinsky2008). These observations may suggest that the gender system itself is intact, and it is only gender assignment that is vulnerable. Note, however, that a small subset of the speakers (9 individuals) seem to have no gender system at all, in that they only produce masculine forms (for nouns of all genders). Lohndal & Westergaard (2016) therefore argue that attrition of grammatical gender involves general erosion of gender assignment, which may eventually lead to a complete loss of gender distinctions.Footnote 6

4.3. Dialect Change

Many languages in the Germanic family have undergone changes in their grammatical gender systems, either a reduction from three to two genders (Dutch, Swedish, and Danish) or the complete loss of gender (English).Footnote 7 As mentioned in section 1, Norwegian dialects have traditionally retained a stable three-gender system, with the notable exception of the Bergen dialect, which changed into a two-gender system due to language contact with low German during the Hansa period (for example, Jahr 1998, Reference Jahr2001). Historically, it is known that the degree of correlation between gender and declension varies across Germanic languages (Kürschner & Nübling 2011), and there has been a diachronic tendency to align gender and declension in West Nordic (Bjorvand Reference Bjorvand1972, Enger Reference Enger2004a, Berg Reference Berg, Fabrizio and Cennamo2019).

In addition to the Bergen dialect, other contact varieties of Norwegian have also lost the feminine gender. This has taken place in dialects spoken in Northern Troms, where Norwegian has been in extensive contact with Saami and Kven (a variety of Finnish; Conzett et al. Reference Conzett, Johansen and Sollid2011). Furthermore, urban ethnolects spoken in Norway have been shown to display a gender system without the feminine (Opsahl Reference Opsahl2009). In both cases, nouns which previously displayed feminine agreement are now used with masculine agreement, which means that the new gender system has two genders, common (masculine + feminine) and neuter. Interestingly, the declensional suffixes are typically not affected by this change. Thus, while the feminine indefinite article ei is replaced by masculine en, the definite suffix is retained, resulting in the following pattern, which is also found in child language and heritage language data (see sections 4.1 and 4.2):

(6)

Recent studies indicate that this change is occurring also in other Norwegian dialects. Investigating a corpus of Oslo speech, Lødrup (Reference Lødrup2011) shows that the feminine gender is more or less lost among speakers in the capital, with older speakers using feminine forms very rarely and young speakers hardly at all. A similar development has been attested in Tromsø, in the north of Norway. Rodina & Westergaard (2015) carried out an experimental study with five age groups, showing that the feminine gender forms are rapidly losing ground: The feminine indefinite article ei is attested only between 7% and 15% of the time among three age groups of children, while adults (age 30 and above) use this form virtually 100% of the time, and teenagers are in the middle with 56% feminine forms. The same study has recently been carried out in Trondheim, a larger city in the middle of the country. The results show that the development toward a two-gender system is even more advanced there, with the youngest children producing the feminine form ei only 4% and adults as little as 35% of the time (Busterud et al. Reference Busterud, Lohndal, Rodina and Westergaard2019). In both locations, the definite suffix is virtually unaffected, however, leading to a system similar to that illustrated in 6.Footnote 8 This means that there is a simplification in the gender system, but a corresponding addition of complexity in the declension system, in that the new common gender now has two classes, the -en class and the -a class (corresponding to previously masculine and feminine nouns, respectively).

Lundquist et al. (Reference Lundquist, Rodina, Sekerina and Westergaard2016) use a Visual World Paradigm experiment to study noun anticipation effects triggered by the three gender forms of the indefinite article in two dialects in Northern Norway: Tromsø and Sortland (see also Lundquist & Vangsnes Reference Lundquist and Vangsnes2018 on yet a different dialect combination). This paradigm is ideally suited for studying how speakers make use of the gender form of an article to predict an upcoming target noun, and it has been widely applied to the study of grammatical gender (for example, Dahan et al. Reference Dahan, Swingley, Tannenhaus and Magnusson2000, Dussias et al. Reference Dussias, Valdés Kroff, Tamargo and Gerfen2013, Hopp Reference Hopp2016). Lundquist et al. (Reference Lundquist, Rodina, Sekerina and Westergaard2016) find that even though the Sortland speakers still make a three-way gender distinction in their production, they do not seem to use gender cues (that is, gender forms of the indefinite article) to anticipate feminine or masculine nouns. This is different for speakers of a (stable) two-gender dialect (the Tromsø speakers), who use the masculine as a predictive cue. Neuter is a predictive cue for speakers of both dialects. Based on these findings, Lundquist et al. (Reference Lundquist, Rodina, Sekerina and Westergaard2016) argue that in a context of language change (exemplified by the Sortland dialect), comprehension is affected before production.

Many factors have been suggested as the cause of the loss of feminine gender. Sociolinguistic factors are commonly used to explain the current development, focusing on what has been referred to as “educated casual style” (Torp Reference Torp, Bandle and Braunmüller2005:1428), a conservative variety of Bokmål, which has recently come to be considered a “posh” way of speaking in urban areas. As this style typically uses a two-gender system (that is, common and neuter), feminine forms are increasingly considered old-fashioned, rural, and “uncool” (Rodina & Westergaard 2015, Busterud et al. Reference Busterud, Lohndal, Rodina and Westergaard2019, Reference OpsahlOpsahl, this issue). However, some linguistic factors are also at play: Simplification is a common result of L2 acquisition and language contact, especially in morphology (see, in particular, Trudgill Reference Trudgill and Lohndal2013). Furthermore, the considerable syncretism between the masculine and the feminine makes it difficult to distinguish the feminine forms in acquisition (as the masculine forms are massively more frequent). Finally, the loss of the true gender forms and the retention of declensional suffixes has been related to the fact that the latter are acquired early (around the age of two), while the former are typically not target-consistent in place until age 6–7 (Rodina & Westergaard 2013, 2015). It is a generally accepted view that forms that are acquired early should be stable, while late-acquired properties are more vulnerable to change.

To summarize the discussion of stable versus vulnerable cues, across the different scenarios of acquisition, attrition, and dialect change, the following generalizations emerge: i) Feminine gender is subsumed by masculine in acquisition and attrition, and is thus also subject to diachronic change; ii) Even though it is acquired relatively late, neuter gender is stable; and iii) Free-standing gender forms develop differently from suffixes, in that the latter are acquired early and do not undergo change. In section 3, we asked how grammatical gender in varieties of Norwegian could be formalized in order to account for the findings from acquisition, attrition, and change (question iv). In the next section, we address this question and consider one way to account for these generalizations.

5. Toward a Formal Analysis

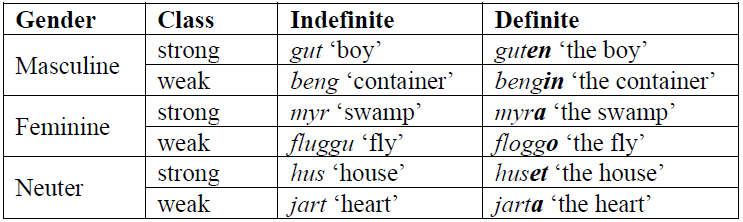

Given the data reviewed in section 4 together with the theoretical background in section 3, we now try to develop a formal analysis that can account for the findings. Let us first outline what this analysis should capture:

(7)

The facts behind 7a–e have been discussed above, while 7f refers to data such as 8.

(8) [At Marie kommer på konserten,] er spesielt.Footnote 9

that Marie comes on concert.def is special.n

‘That Marie comes to the concert is unusual.’

Sentential subjects do not have any gender features, yet the agreement on the postcopular adjective is neuter (across all dialects) and not the common form. This suggests that neuter is the default agreement gender in Norwegian, that is, the gender that shows up in the absence of any gender cues (“neutral agreement” in the words of Corbett & Fraser Reference Corbett, Fraser, Unterbeck and Rissanen1999). In contrast, default gender assignment in Norwegian is clearly masculine. Thus, one needs to distinguish between different types of defaults in Norwegian: An agreement default (neuter) and an assignment default (masculine; see Corbett & Fraser Reference Corbett, Fraser, Unterbeck and Rissanen1999, Enger Reference Enger2009).

How can one formalize the Norwegian gender systems in a way that also captures the directionality of the ongoing change? Using formal features, a range of options exist; space does not allow us to consider all of them and the question of whether or not the difference is notational or substantial. A core element in the analysis concerns the choice of the default. Here our attention is limited to the syntactic default, neuter.Footnote 10 We are also assuming that features can be multivalued, acknowledging that there are a range of issues facing the choice of feature ontology (see Corbett Reference Corbett2012 and Bank Reference Bank2014). Our proposal, then, involves the features in 9, which would be located on the categorizer n within a DM analysis (compare Kramer Reference Kramer2015). An empty feature matrix for neuter means that it is the default, or underspecified gender.Footnote 11

(9)

Turning to two-gender dialects, we argue that in these varieties, [gen: fem] has been lost, which forces a reanalysis of masculine gender, resulting in the following feature system:

(10)

Neuter has the same feature representation in both gender systems, since it is completely unaffected by the change.

Next, we consider the definite suffix and its relation to free morphemes (that is, true gender forms, according to Hockett Reference Hockett1958 and Corbett Reference Corbett1991). In section 3, we showed that the definite suffix in Norwegian has a controversial status, some arguing that, although it is an element that is attached to the noun and therefore does not agree with it, it is nevertheless an exponent of gender. In section 4, we reviewed data from acquisition, attrition, and change showing the difference between gender agreement on other words (for example, the indefinite article) and suffixes (expressing number and definiteness). Like Rodina & Westergaard (2015) and Lohndal & Westergaard (2016), we interpret these findings as evidence that the suffixes are different from true gender markers. More specifically, we develop an analysis whereby the definite suffix is considered a marker of declension class (see discussion in section 4.2). Typically, a dialect with the new two-gender system, as in 10, would have the declension classes and exponents in the singular definite shown in 11.

(11)

In many three-gender dialects (with the exception of dialects such as Oppdal, see table 2), there is a one-to-one correspondence between declension and gender: Classes I, II, and III correspond to masculine, feminine, and neuter, respectively, raising the question whether gender predicts declension class or declension class predicts gender (Enger Reference Enger2004a, Berg Reference Berg, Fabrizio and Cennamo2019). In a two-gender system with only common and neuter gender, there is a less transparent relationship between gender and declension class, in that common gender consists of two declension classes (I and II). Neuter declension class can then be treated as the elsewhere case, on a par with our analysis of neuter gender. Following Kramer’s (Reference Kramer2015) analysis outlined in section 3, a previously feminine noun phrase such as en bok ‘a book’ would then have the following analysis:

(12)

Example 12a is the narrow syntactic structure, whereas 12b is the structure after the declension class feature adjoins to the categorizing head in the postsyntactic component. The spell-out of 12a is boka, the relevant form in many dialects.

6. Conclusion

In this paper, we have discussed aspects of the grammatical gender system in varieties of Norwegian, relying on evidence from acquisition, attrition, and dialect change. We have identified a common pattern: The feminine gender is vulnerable, which is clearly seen in the disappearance of the indefinite article. The definite suffix, however, is not problematic: It is acquired early and shows no signs of either attrition or change. We have proposed an outline of a formal analysis that can capture the transition from a three- to a two-gender system in Norwegian, both for gender markers proper and for declension class markers.

Previous research is divided in terms of whether there are predictive cues for gender assignment in varieties of Norwegian. However, most of this work only considers gender assignment based on Norwegian words. As emphasized by Corbett (Reference Corbett1991), Thornton (Reference Thornton2009), and Audring (Reference Audring2016), among others, it is necessary to investigate gender assignment to loan words and nonce words to “uncover psychologically real and productive criteria that speakers exploit in ‘on-the-spot’ gender assignment” (Thornton Reference Thornton2009:17) rather than appeal to what Comrie (Reference Comrie1999:461) has labeled “postfactum rationalizations,” which often characterize some of the gender assignment generalizations proposed in the literature. As discussed in section 2, the picture for Norwegian is rather unclear when it comes to the nature of gender assignment. Much more research is needed in order to uncover the subtle cues and tendencies that speakers seem to be sensitive to.