Background

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by the novel SARS-CoV-2 virus strain emerged in Wuhan, China in late 2019 and has since been declared a pandemic.Reference Wang, Horby, Hayden and Gao1 As of 21 April 2020, there have been over 2.4 million people with COVID-19 and 163 thousand deaths because of COVID-19 worldwide, with about half in the European region. The UK, the fifth most affected country, has reported over 124 000 people with COVID-19 and over 16 500 deaths.2 The challenges of this pandemic to health systems, such as the National Health Service in the UK, include workforce scarcity, insufficient infrastructure and limited testing capacity.Reference Willan, King, Jeffery and Bienz3

During epidemics, people with psychiatric disorders may be more susceptible to infections, experience complications and have more difficulties accessing health services.Reference Yao, Chen and Xu4 Individuals with psychiatric disorders have been shown to have impaired access to somatic healthcare and physical health screeningReference Lamontagne-Godwin, Burgess, Clement, Gasston-Hales, Greene and Manyande5,Reference Rodgers, Dalton, Harden, Street, Parker and Eastwood6 because of a mismatch between patient needs and health systemsReference Björk Brämberg, Torgerson, Norman Kjellström, Welin and Rusner7,Reference Nease8 and stigma;Reference Nankivell, Platania-Phung, Happell and Scott9 therefore, many psychiatrists are worried that patients with psychiatric and substance use disorders may be precluded from receiving timely and appropriate testing.Reference Druss10

In addition, individuals with a psychiatric disorder may be at increased risk for COVID-19 complications because of comorbid conditions (cardiovascular, respiratory and metabolic conditions, such as obesity)Reference Simonnet, Chetboun, Poissy, Raverdy, Noulette and Duhamel11–Reference Rubino, Kelvin, Bermejo-Martin and Kelvin14 and potential reduced adherence with government measures. However, these issues have remained debatable given the current lack of epidemiological data on associations between psychiatric disorders and COVID-19 testing rates and testing outcomes. More research has therefore been called for to address these questions during and after the COVID-19 pandemic.Reference Holmes, O'Connor, Perry, Tracey, Wessely and Arseneault15

Aims

To address the questions of whether psychiatric disorders have any association with frequencies of testing and the results of such tests, we have targeted a large population-based study (the UK Biobank)Reference Bycroft, Freeman, Petkova, Band, Elliott and Sharp16,17 to perform association analyses of psychiatric disorder diagnoses with COVID-19 testing probability and such test results. We hypothesised that people with psychiatric disorders are tested for COVID-19 less frequently than people without a psychiatric disorder and that people with psychiatric disorders more frequently test positive than people without psychiatric disorders.

Method

The full UK Biobank cohort consists of 502 505 individuals recruited between 2006 and 2010, out of which 157 366 participants have information on a mental health questionnaire.Reference Davis, Coleman, Adams, Allen, Breen and Cullen18 The composition, set-up and data gathering protocols of the UK Biobank have been extensively described elsewhere.Reference Sudlow, Gallacher, Allen, Beral, Burton and Danesh19,Reference Miller, Alfaro-Almagro, Bangerter, Thomas, Yacoub and Xu20 We made use of data from UK Biobank participants whose COVID-19 test results were released on 21 April 2020 under application access code 55392.Reference Pinzón-Espinosa21 COVID-19 test results in the UK Biobank, reported in data field 40 100, are mostly derived from samples from nose/throat swabs (or a lower respiratory tract sample in intensive care settings), on which polymerase chain reaction is performed. The UK Biobank data field 40 100 is accompanied by the following statement: ‘We are releasing COVID-19 test results from 16 March 2020 onwards, as after this date UK testing was largely restricted to those with symptoms in hospital. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 from samples taken from hospitalized patients after this date can, at least for now, be viewed as a surrogate for severe disease.’22 The first data wave released comprises results from 16 March to 16 April, 2020.22 Before analyses, duplicate entries of test results were removed from the COVID-19 testing results by selecting the latest test results for each participant.

UK Biobank has received ethics approval from the National Health Service National Research Ethics Service (ref 11/NW/0382). We used the STROBE cross-sectional reporting guidelines to assess research quality.Reference von Elm, Altman, Egger, Pocock, Gøtzsche and Vandenbroucke23

For our main analyses we selected ICD-10 diagnoses from UK Biobank data field 41270.24 We compared testing frequency and testing outcome in individuals with and without a diagnosis of a psychiatric disorder (F codes). To check whether testing frequency and test results resemble other health conditions, we then included several additional ICD-10 diagnoses in the analyses: (a) individuals with respiratory or cardiovascular diseases as these are particularly at risk for admission to hospital following infection with COVID-19 (ICD-10 codes Jxx and I0x–I7x); (b) people with metabolic diseases as these are highly prevalent among people with psychiatric disorders and may contribute to much of their generally poor health (codes E0x–E1x and E4x–E7x); and (c) those with central nervous system neurological disorders, as a comparison category of diseases resembling psychiatric disorders with regards to symptomatology and hypothesised neurobiological underpinnings (G0x–G4x). A more detailed description on conditions included is available in the supplementary Table 1 (available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2020.75).

Subsequently, we investigated each of the major psychiatric disorder categories with a prevalence above a threshold of 5% (n = 74) among individuals within the subsample that had test results available. We therefore included substance use disorders (F1x), mood disorders (F3x), and anxiety disorders (F40–F41) in the analyses.

All data was analysed in R v3.6.1.25 We applied two statistical tests to answer the following primary research questions.

(a) Are people with a psychiatric disorder more or less likely to undergo COVID-19 testing than people without such a diagnosis? To answer this first question, we used two-sided Fisher's exact tests to examine distributions of individuals tested compared with the full UK Biobank cohort.

(b) Are people with a psychiatric disorder more or less likely to test positive for COVID-19 compared with those without such a diagnosis? To answer this second question, we ran logistic regression models, using the COVID-19 test results as a dichotomous outcome (negative/positive), with the ICD-10 diagnoses or mental health categories as predictors. We report the change in log odds (β) from these models.

Age, gender, body mass index and assessment centre were used as covariates in the logistic regression models as the first three have been associated with both psychiatric disorders and COVID-19, and assessment centre was added to these models to prevent regional differences having an impact on the results. To assess the robustness of our findings, we further ran a sensitivity analysis additionally covarying for socioeconomic status, as measured through the Townsend Deprivation Index, which has previously been used in the UK Biobank,Reference Tyrrell, Jones, Beaumont, Astley, Lovell and Yaghootkar26,Reference Townsend, Phillimore and Beattie27 and pre-existing cardiovascular, respiratory and metabolic conditions as these are commonly observed in people with psychiatric disorders.

Secondary analyses included population-level information on mental health based on mental health questionnaire items asking participants whether they had ever experienced a core symptom of the major mental health categories (data category 136). For example, the two questions on depression were ‘Have you ever had prolonged feelings of sadness or depression?’ and ‘Have you ever had prolonged loss of interest in normal activities?’, tapping into the two core symptoms of major depressive disorder of depressed mood and anhedonia.Reference Malhi and Mann28 If participants had an affirmative response to either of these items, we scored the depression mental health category as present, otherwise as absent. This way, we aimed to examine relationships of the presence versus absence of mental health symptoms (depressive, manic, anxiety, addiction, psychotic experiences, self-harm and happiness items) with both testing probability and testing results in this general population cohort. To test this, we used identical analysis approaches as for the primary analyses, i.e. Fisher's exact tests and logistic regression with the same covariates as mentioned above. We also ran a sensitivity analysis for this secondary analysis by including the abovementioned additional covariates, similar to the primary analyses. We ran these analyses with and without including individuals with a diagnosis of psychiatric disorder to disentangle whether people with any such diagnosis are driving results, and to what extent continuous measures of mental health are associated with COVID-19 testing probability and outcome. Please see the supplementary Tables 2 and 3 for an overview of all mental health items and more information on these analyses.

Results

The UK Biobank subsample with COVID-19 test results available consisted of 1474 unique individuals. Of these, 842 tested negative (57.1%) and 632 tested positive (42.9%) for the virus. Individuals tested were significantly older than those not tested in the UK Biobank (58.2 years (s.d. = 8.8) v. 57.0 years (s.d. = 8.1); P = 2.2 × 10−7), there were more men among those tested (54.4%) than among those not tested (46.6%), P = 2.1 × 10−9, and the average Townsend Deprivation Index was lower among those tested than among those not tested (−0.16 (s.d. = 3.53) v. −1.30 (s.d. = 3.09), P < 10−16). There were no significant differences in age (P = 0.51), gender (P = 0.14) or socioeconomic status (P = 0.13) between those testing positive versus negative.

COVID-19 testing and ICD-10 diagnoses

Individuals with a psychiatric disorder were overrepresented among those tested, making up 23% of this sample compared with 10% in the full UK Biobank cohort (P < 0.0001; Table 1). This overrepresentation was similar to, or even higher than, that of people with diagnoses of cardiovascular, respiratory, metabolic, or neurological conditions (Table 1). Furthermore, this overrepresentation was also present for each of the specific psychiatric disorder categories investigated (Table 1).

Table 1 Comparison of number of individuals present in the full UK Biobank cohort with those among the COVID-19 tested subset, per diagnostic group, ordered by decreasing ratioa

a. The columns indicate the number of individuals with a specific diagnosis in either the full UK Biobank cohort or in the tested subset, and the resulting ratio. The numbers in brackets indicate the corresponding percentage of individuals. The P-value is determined by Fisher's exact test.

In Table 1, the numbers of the individual categories add up to more than the total number of tested individuals. This is because of comorbidity i.e. the majority of individuals in the UK Biobank have more than one ICD-10 diagnosis, and particularly individuals with psychiatric disorders have high rates of comorbidity. We have provided an overview of this comorbidity in Supplementary Table 2.

Among those tested, individuals with a diagnosis of a psychiatric disorder significantly less frequently tested positive for COVID-19 compared with those without such a diagnosis (P = 0.01, β = −0.35; Fig. 1a). When looking into specific psychiatric disorders, we found that particularly individuals with substance use disorders were significantly less likely to test positive (P = 0.0002; β = −0.70; Fig. 1b). Although people with anxiety and depressive disorders were also less likely to test positive than those without such a diagnosis, these results were non-significant.

Fig. 1 Bar plot of change in log odds for testing positive, by ICD-10 diagnosis.

The pattern of results did not change in our sensitivity analysis where we additionally covaried for pre-existing cardiovascular, respiratory and metabolic conditions, as well as socioeconomic status; both general psychiatric disorder and substance use specifically remained significantly associated with test outcome (Supplementary Fig. 1).

COVID-19 testing and mental health

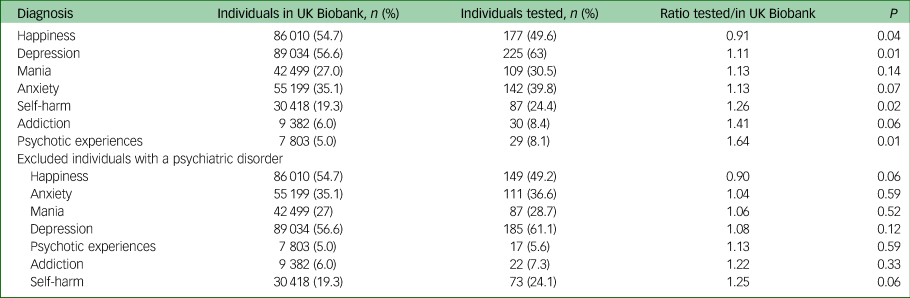

Please see Table 2 for the prevalence of affirmative responses to mental health items among the full UK Biobank cohort versus those among individuals tested for COVID-19. As shown in the top half of Table 2, there were significant differences in responses between those in the full cohort compared with those in the tested subsample. However, these differences were much smaller than those found for diagnostic categories, and they were no longer significant after excluding individuals with a psychiatric disorder (bottom half).

Table 2 Comparison of number of individuals in the full UK Biobank cohort and those among the COVID-19 tested subset, per mental health questionnaire categorya

a. The columns indicate the number of individuals with an affirmative response to a specific category in either the full UK Biobank cohort, or among the tested subset, and the resulting ratio. The numbers in brackets indicate the corresponding percentage of individuals. The P-value is determined by Fisher's exact test. The top half of the table indicates numbers across all participants, the bottom half the numbers after excluding individuals with a psychiatric disorder diagnosis.

We further found no statistically significant associations between responses to the mental health items and test results, as shown in Fig. 2. These results stayed the same after correcting for the additional covariates (see supplementary Figures 2 and 3 for the full results).

Fig. 2 Bar plots of odds ratios for testing positive, per mental health category based on affirmative responses to mental health questions in the mental health questionnaire in the UK Biobank, after excluding individuals with a psychiatric disorder diagnosis.

Discussion

Main findings

Contrary to our hypotheses, we found that individuals with psychiatric disorders have been more frequently tested for COVID-19 compared with those without a diagnosis. Furthermore, among those tested, individuals with psychiatric disorders, substance use disorders in particular, had lower odds of testing positive than individuals without such a diagnosis. We believe these are important findings as they carry the potential to reduce stigma: while people in the general population may be concerned that individuals with psychiatric disorders do not comply with containment measures and are thus susceptible to contract COVID-19 our findings may help counter such concerns. Our findings also may help diminish concerns over limited healthcare access preventing people with psychiatric disorders from undergoing testing.

Interpretation of our findings

Before we elaborate on explanations for our findings, it is important to contextualise the high rate of positive tests relative to the total test number in the UK Biobank total study population (42.9%). The UK Biobank data provided testing results gathered from 16 March to 16 April 2020, when it was not part of any routine visit or protocol; as per the UK Biobank data-release information provided to researchers, only people showing severe symptoms were tested. Our data-set reflects the beginning of the pandemic in the UK, when testing was largely restricted to those with symptoms in hospital, i.e. people with severe cases, and when testing capacity was low. In this regard, the UK Biobank states that SARS-CoV-2 testing can be viewed as a surrogate for presentation of severe COVID-19 symptoms.22

Possibly, people with psychiatric disorders are being tested more frequently because of comorbid conditions, higher levels of anxiety about contracting COVID-19 or perhaps a combination of both. Furthermore, referring physicians’ concerns about COVID-19 in people with psychiatric disorders may contribute to relatively high testing rates. Such reasoning may also, at least in part, explain higher rates of negative COVID-19 test results in people with psychiatric disorders.

Frequently observed negative test results could also be related to their higher chances of somatic illness relative to individuals without such a diagnosis or even with other pre-existing conditions. For example, patients with psychiatric disorders may present to hospitals with COVID-19-like symptoms but could be presenting an exacerbation of chronic pulmonary disease related to high rates of smoking, metabolic syndrome and sedentary lifestyle, further aggravated by late presentation to healthcare services because of poor living conditions or lack of social support. Such situations in patients with a history of psychiatric illness may lead to higher likelihoods of presentations of acute somatic illness requiring admission to hospital and thus, from March 2020 onwards, COVID-19 testing.

A final underlying reason for the low chances of positive COVID-19 testing in patients with a psychiatric history may be that they live relatively more socially isolated than people without such diagnoses. A non-controlled study has shown people with psychosis and mood disorders have about 1.7 social contacts in a week outside home, workplace or healthcare settings, and moderate feelings of loneliness.Reference Giacco, Palumbo, Strappelli, Catapano and Priebe29 Furthermore, a study on the relationship between living alone and psychiatric disorders using the 1993, 2000, and 2007 National Psychiatric Morbidity Surveys in the UK found a positive association between both variables that was up to 84% explained by loneliness.Reference Jacob, Haro and Koyanagi30 Among young adults in modern Britain, relatively lonely individuals have been shown to be more likely to have depressive, anxiety, and alcohol use disorders.Reference Matthews, Danese, Caspi, Fisher, Goldman-Mellor and Kepa31 Thus, lonelier, more socially isolated people such as those with psychiatric disorders may normally, and now even more so, be in confinement and have less social contact than people without psychiatric disorders, reducing the likelihood of testing positive for COVID-19.

Our results also show the frequency of individuals with a neurological condition undergoing testing being high, comparable with psychiatric disorders in the UK Biobank sample. This could be explained from a symptom-level perspective: psychiatric disorders show the most substantial overlap with neurological disorders regarding symptom domains such as cognitive function, behavioral alterations and mood. One example would be the high rates of depressive symptoms in Parkinson's diseaseReference Poewe, Seppi, Tanner, Halliday, Brundin and Volkmann32 and multiple sclerosis.Reference Silveira, Guedes, Maia, Curral and Coelho33 Furthermore, dementias and other types of brain disorders causing behavioral symptoms are grouped within psychiatric disorders in ICD-10;24 these show high degrees of symptom overlap with neurodegenerative disorders, especially regarding mood and cognitive functioning.Reference Scarioni, Gami-Patel, Timar, Seelaar, van Swieten and Rozemuller34,Reference Leyhe, Reynolds, Melcher, Linnemann, Klöppel and Blennow35 Therefore, people with neurological conditions, either comorbid with psychiatric conditions or presenting symptomatology overlapping with psychiatric symptoms, being both within the realm of brain functioning, would be expected to be affected similarly in the context of COVID-19.

Furthermore, when looking at the symptom level in the UK Biobank sample (mental health questionnaire items), no relationship was found between testing likelihood or outcome and continuous measures of depressive, manic, anxiety, addiction, psychotic experiences, self-harm or happiness items in those without a past or current diagnosis of psychiatric disorder. Therefore, people with clinical cases of psychiatric disorders, and not subsyndromic individuals, appear to drive our primary findings. Statistical power may currently hamper these analyses.

Limitations

Limitations of this study include the relatively small sample size, the fact that the UK Biobank is not fully representative of the general population,Reference Keyes and Westreich36–Reference Abdellaoui38 absence of replication in other cohorts and lack of information on indications for testing at the level of the individual. The small sample size precluded individuals with diagnoses of some less prevalent psychiatric disorders, such as schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder and bipolar disorders, to be represented in the analyses. Furthermore, assessment centre was used as a proxy for geographical location, and this variable was set at the start of recruitment, for example if individuals moved after the initial assessment this was not possible to take this into consideration.

Finally, detailed clinical information on indications for testing are unavailable for each individual, precluding us from running subgroup analyses per clinical indication. Nonetheless, the UK Biobank data gathered testing results from 16 March 2020 onwards when it was not part of any routine visit or protocol; as per the UK Biobank data-release information provided to researchers, only people showing severe symptoms were tested. This makes it relatively likely that patients were not tested routinely prior to admission for psychiatric reasons. Furthermore, although we believe having testing rates of other complementary exams would have been helpful to compare the COVID-19 testing with routine testing, we do not have information on other diagnostic procedures during admission, such as urine toxicology.

Implications

Despite the aforementioned limitations, two preliminary conclusions can be drawn based on the current data-set given the convergence of findings for a range of psychiatric disorders and similarities between testing probabilities. First, individuals with a psychiatric disorder are not less likely to undergo testing for COVID-19 than those without psychiatric disorders. Second, patients with psychiatric disorders do not test positive more frequently than people undergoing testing without such conditions. We encourage other researchers to perform similar analyses in other cohorts, as well as further research when more data from the UK Biobank become available, for example into associations between extended psychiatric symptom-level data, COVID-19 symptom severity and mortality.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2020.75.

Data availability

UK Biobank data are available through a procedure described at http://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/using-the-resource/.

Acknowledgements

The authors are extremely grateful to the participants who took, and continue taking, part in the UK Biobank cohort study. This research has been conducted using the UK Biobank Resource under Application Number 55 392. The authors also thank Tobias Kaufmann for his input to our analyses and manuscript.

Author contributions

All authors conceived the study and interpreted the results. D.v.d.M. analysed the data. J.P.-E., D.v.d.M. and J.J.L. wrote the manuscript, which was revised by B.D.L., J.K.T., C.H.V. and S.G. J.P.-E. and D.v.d.M. are the guarantors.

Declaration of interest

All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; J.P.-E. declares he has served as a CME speaker for Lundbeck, unrelated to this work, while the rest of the authors declare no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

ICMJE forms are in the supplementary material, available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2020.75

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.