Introduction

In many Western countries, governments see active citizenship as an important theme. A neoliberal philosophy has influenced and changed health-care systems during the last decade. Now, citizens should take personal responsibility and participate in society as independent individuals. This responsibility also concerns health and welfare (Verhoeven and Tonkens, Reference Verhoeven and Tonkens2013). The worldwide trend in health care is that older adults with chronic conditions and physical impairments continue to live at home (Cartier, Reference Cartier2003; Bjornsdottir, Reference Bjornsdottir2009; Jacobs, Reference Jacobs2019). Policies are directed towards self-management and informal care from family and friends.

If living at home is no longer possible – e.g. due to severe physical impairments – admission to a residential care facility (RCF) is permitted. How is participation achieved in a facility that is a place to live as an individual, as well as a place where the resident is dependent on others to receive appropriate care? The authors focus on older adults with psychical impairments due to age-related decline and chronic health conditions (further to be called: residents with physical impairments). Generally speaking, these persons are able to make decisions on how they want to live their lives, but are often not able to execute the decisions they make themselves. The focus of this review article is to gain insight into which facilitators and barriers influence autonomy of older adults with physical impairments.

Living in residential care influences autonomy. The authors are investigating this influence because they have the presumption that intervening on these facilitators and barriers for this specific group will create better opportunities for their autonomy.

The concept of participation is discussed in the light of diverse psychological and sociological research and is described with words such as ‘control’, ‘agency’, ‘mastery’, ‘autonomy’, ‘self-management’ and ‘self-determination’ (Morgan and Brazda, Reference Morgan and Brazda2013). The authors of the current review chose to use the word autonomy because of the decisional versus executional polarity. This polarity was described by Collopy (Reference Collopy1988) as follows: a resident can have a desire and make decisions on how she/he wants to live her/his life, even if she/he cannot actualise them.

Moreover, in RCFs, several residents with physical impairments live together and can simultaneously have incompatible needs and wishes (Bolmsjö et al., Reference Bolmsjö, Sandman and Andersson2006). Autonomy is given shape in a relational context between staff and other residents (Abma et al., Reference Abma, Bruijn, Kardol, Schols and Widdershoven2012; Baur and Abma, Reference Baur and Abma2012; Gleibs et al., Reference Gleibs, Sonnenberg and Haslam2014; Oosterveld-Vlug et al., Reference Oosterveld-Vlug, Pasman, van Gennip, Muller, Willems and Onwuteaka-Philipsen2014). McCormack (Reference McCormack2001) challenges the ‘individualistic concept of autonomy’ as used in neoliberal tradition and gives a different view based on interconnectedness and person-centred care.

The aforementioned relationship between autonomy and person-centred care can help to study autonomy in more detail. The aim of person-centred care is to place residents at the centre: in other words, each resident is seen as a unique person with a personal history, future and life goals. With person-centred care, care-givers can respect and enhance autonomy of residents in the last phase of their lives (Danhauer et al., Reference Danhauer, Sorocco and Andrykowski2006; Donnelly and MacEntee, Reference Donnelly and MacEntee2016). McCormack and McCance (Reference McCormack and McCance2017) formulated a leading theory of person-centred practice (PCP) which can help to reflect upon facilitators and barriers to autonomy. It offers a theoretical, evidence-based framework. PCP is seen as a multi-dimensional concept and it is still developing. It takes into account person-centred outcomes (e.g. involvement in care), person-centred processes (e.g. sharing decision-making), the care environment (e.g. appropriate skills mix in the nursing team), prerequisites of staff (e.g. providing holistic care) and the macro context (e.g. health and social care policy) (McCormack and McCance, Reference McCormack and McCance2017).

A better understanding of the factors that strengthen autonomy (facilitators) or undermine autonomy (barriers) can help to enhance practices in RCFs that lead to interventions to preserve and facilitate autonomy of older adults with physical impairments living in RCFs. For a better understanding, the authors will underpin the concept of autonomy for older adults living in RCFs with a description that will be derived from the literature.

A systematic literature review will be executed with the research question: which facilitators and barriers to autonomy of older adults with physical impairments due to ageing and chronic health conditions living in RCFs are known?

Method

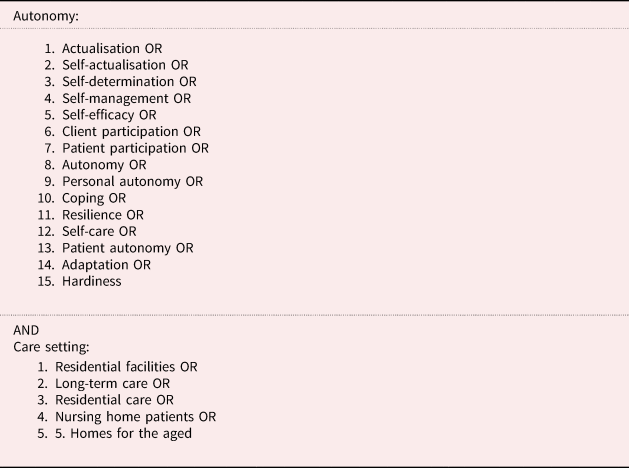

To answer the research question, a systematic literature search was conducted in the following databases: PubMed, CINAHL, Social Services Abstracts, Sociological Abstracts and PsycINFO. These databases include articles about care, cure and psycho-social functioning. For the central aspects, living in an institution for long-term care and autonomy, the thesaurus (Social Services Abstracts, Sociological Abstracts and PsycINFO), MESH terms (PubMed) and headings (CINAHL) were used to select search terms that best matched the research question (Table 1). The search was conducted in March 2016 and updated in July 2017. A limit of ten years (beginning from 2006) was chosen, because the neoliberal approach of participation and the role of autonomy has only been put into laws and regulations over the last decade. The question of how autonomy can be enhanced for the more vulnerable members of society also emerged in this period.

Table 1. Search terms and strategy

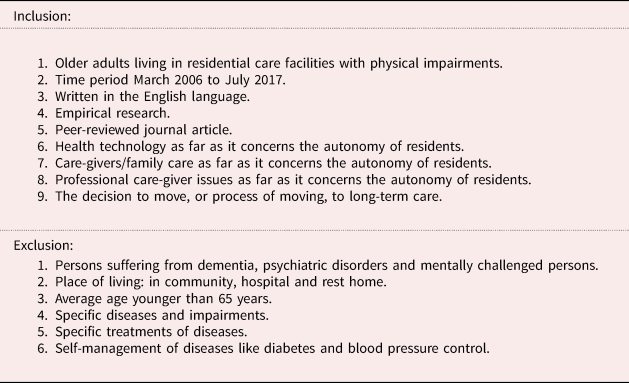

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were established to be sure to review articles that concern the residents under study, namely older adults with physical impairments due to ageing and chronic conditions who live in RCFs (Table 2).

Table 2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for autonomy and its facilitators and barriers

Selection

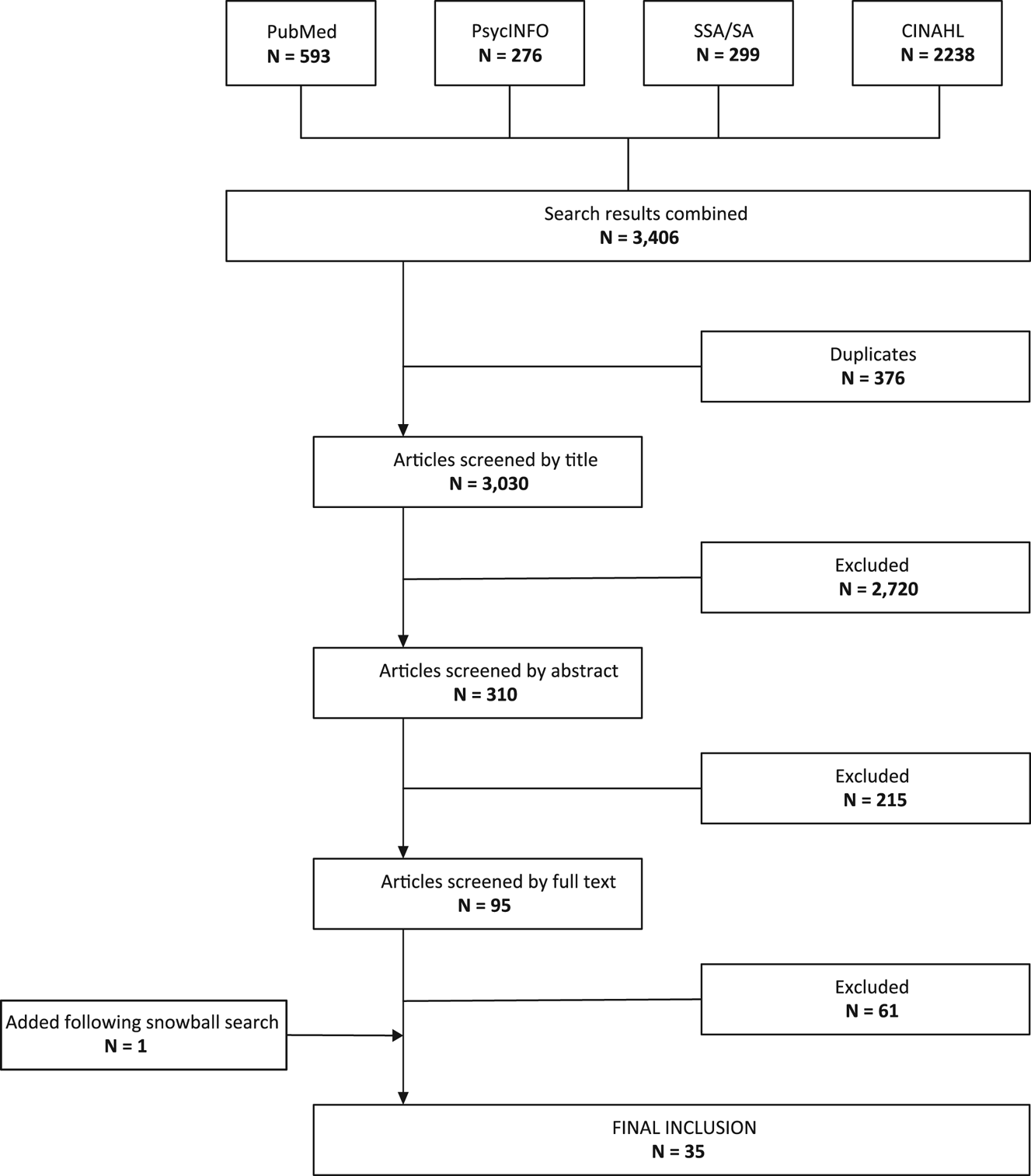

Figure 1 shows the results of the database search. Using the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 2), the titles of the 3,030 unique articles were screened by the first author (JvL). When in doubt, the article went to the next stage. Selection by abstract was performed independently by JvL and three co-authors (KL, IdR and BJ). These co-authors each reviewed one-third of the articles and JvL reviewed all the articles. Afterwards, the selections were discussed in pairs of reviewers in order to reach a consensus. When no consensus was reached on an article, it was included in the next stage. The same procedure was followed for the full-text selection. When no consensus about inclusion or exclusion was reached in this stage, a third author was consulted and a consensus was reached.

Figure 1. Flowchart of the database search of facilitators and barriers to autonomy.

Note: SSA/SA: Social Services Abstracts and Sociological Abstracts.

Data extraction and quality assessment of the articles

The data extraction of the full texts was performed using a format wherein the authors independently noted the description and the position of autonomy (i.e. cause, mediator or result). Apart from one article (Brandburg et al., Reference Brandburg, Symes, Mastel-Smith, Hersch and Walsh2013), the descriptions were given in the Introduction section in which the authors clarify how they were going to use the concept in their study.

Subsequently, the authors noted facilitators and barriers as given in the Results sections of the articles. Afterwards JvL and KL, JvL and IdR, and JvL and BJ compared and discussed the extracted data in order to compare and interpret the data.

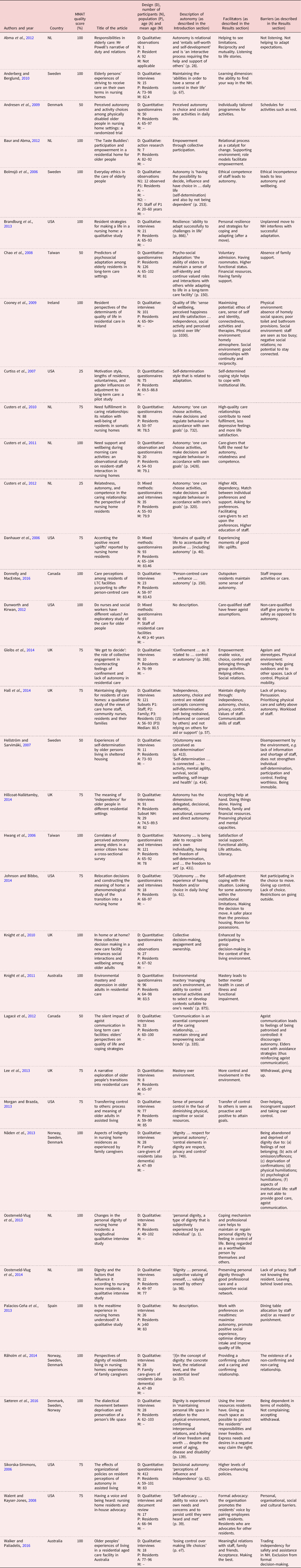

Each article was also assessed on quality, again independently by JvL and KL, IdR and BJ. The results of the assessed quality were also discussed in bilateral sessions. Because the systematic review includes articles with qualitative, quantitative and mixed-methods designs, the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) was used to assess the quality of the selected articles. The MMAT is developed to facilitate the concurrent appraisal of articles with different designs, and provides elements to assess the quality of the articles to be included (Pace et al., Reference Pace, Pluye, Bartlett, Macaulay, Salsberg, Jagosh and Seller2012). In order to do so, four elements for studies with a qualitative or quantitative design are defined; for mixed-method designs, 11 elements are defined. The scores are reported in column 3 of Table 3.

Table 3. Description of the included articles and results

Notes: 1. Given in the Results section. MMAT: Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool. NL: The Netherlands. USA: United States of America. NH: nursing home. ADL: activities of daily living. LTC: long-term care.

Data synthesis

The facilitators and barriers (see Table 3, columns 7 and 8) were organised by JvL, KL, IdR and BJ in three themes derived from the PCP framework (McCormack and McCance, Reference McCormack and McCance2017). Because a large group of facilitators and barriers found in the included articles concerned the residents themselves, the authors decided to add the theme ‘characteristics of residents’. The current article thus uses four themes that affect autonomy, namely characteristics of residents, prerequisites of professional care-givers in RCFs, processes in the relationship between residents and professional care-givers, and the care environment. When the context of the facilitators and barriers in an included article was not clear enough to assign it to one theme, the authors chose to assign it to more than one.

The included studies did differ in method and quality. However, the authors decided not to exclude the six articles scoring below 75 per cent because they provided relevant information on the research question. Moreover, in the analyses and presentation of the results, articles with a low MMAT score will not dominate.

Elements from the descriptions (Table 3, column 6) were used to make a general description of autonomy for older adults with physical impairments in RCFs.

Reliability

The authors started with an individual review of ten abstracts using the inclusion and exclusion criteria. In a meeting, they discussed the similarities and differences in the selection. The same was done in the stage of the full-text selection, this time with two articles. In this way, a uniform selection procedure of abstracts and full texts was achieved. At each selection stage, the first author (JvL) reviewed all the articles and the co-authors (KL, IdR and BJ) each reviewed one-third of the articles. The articles were discussed bilaterally between JvL with KL, IdR and BJ. When no consensus was reached, the article was reviewed again in the next stage. At each stage, the articles switched to another reviewer. The stage of data extraction and quality assessment was also preceded by a meeting with all reviewers to discuss the analysis and assessment process.

Results

The search identified 3,030 unique articles, of which 35 were included. Table 3 (column 2) shows that most of the articles originate from North-West Europe, Australia and North America. The MMAT scores (column 3) vary from 25 to 100 per cent. Generally speaking, the methodological quality of the articles is appropriate: the mean quality score is 82.9 per cent and 19 articles score 100 per cent. Column 5 shows us the designs (‘D’). Qualitative designs (23 articles, 65.7%) were used most frequently, followed by quantitative (nine articles, 25.7%) and mixed-methods designs (three articles, 8.6%). Interviewing (22) is the method most used. In three articles, these interviews are combined with questionnaires and one of the interview studies is combined with a document review. There are ten questionnaire studies, of which two combined the questionnaire with observations. The other methods used in the articles are observation (two) and action research (one). Seven articles evaluated the effect of interventions on autonomy. In 32 of the 35 articles (see column 5, ‘P’), the perspective of the resident was explored.

Description of autonomy in the included articles

For a better understanding of the facilitators and barriers to autonomy, the authors first aim to underpin the concept of autonomy for residents with physical impairments. The word autonomy is used in 16 articles (see column 6, description of autonomy, in Table 3). The polarity of decisional and executional autonomy (Collopy, Reference Collopy1988) was mentioned in four articles (Hwang et al., Reference Hwang, Lin, Tung and Wu2006; Sikorska-Simmons, Reference Sikorska-Simmons2006; Hellström and Sarvimäki, Reference Hellström and Sarvimäki2007; Hillcoat-Nallétamby, Reference Hillcoat-Nallétamby2014). Most of the other included articles only used one element of the polarity, the decisional aspect.

Autonomy, self-determination and dignity seem to be linked. Various relationships between these concepts were described in the included articles, as causes, intermediate factors or outcomes of one another. For example, dignity as a cause for autonomy (Nåden et al., Reference Nåden, Rehnsfeldt, Råholm, Lindwall, Caspari, Aasgaard, Slettebø, Sæteren, Høy, Lillestø, Heggestad and Lohne2013). Also, an opposite perspective is mentioned: autonomy, amongst other aspects, leads to dignity (Hall et al., Reference Hall, Dodd and Higginson2014). Dignity as a result of choice and autonomy is also described (Oosterveld-Vlug et al., Reference Oosterveld-Vlug, Pasman, van Gennip, Muller, Willems and Onwuteaka-Philipsen2014). Three articles use the motivational theory of Ryan and Deci (Reference Ryan and Deci2000): in this theory, autonomy leads to self-determination (Custers et al., Reference Custers, Westerhof, Kuin and Riksen-Walraven2010, Reference Custers, Kuin, Riksen-Walraven and Westerhof2011, Reference Custers, Westerhof, Kuin, Gerritsen and Riksen-Walraven2012). Self-determination is also seen as a sub-category of autonomy (Hellström and Sarvimäki, Reference Hellström and Sarvimäki2007).

Based on the elements from column 6 of Table 3 (description of autonomy), a description of autonomy was formulated in such a way that it best matches the population in this review: older residents with physical impairments in RCFs. In the current article, autonomy is described as a capacity to influence the environment (Knight et al., Reference Knight, Davison, McCabe and Mellor2011; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Simpson and Froggatt2013; Sæteren et al., Reference Sæteren, Heggestad, Høy, Lillestø, Slettebø, Lohne, Råholm, Caspari, Rehnsfeldt, Lindwall, Aasgaard and Nåden2016) and make decisions (Bolmsjö et al., Reference Bolmsjö, Sandman and Andersson2006; Hwang et al., Reference Hwang, Lin, Tung and Wu2006; Sikorska-Simmons, Reference Sikorska-Simmons2006; Hellström and Sarvimäki, Reference Hellström and Sarvimäki2007; Walent and Kayser-Jones, Reference Walent and Kayser-Jones2008; Andresen et al., Reference Andresen, Runge, Hoff and Puggaard2009; Cooney et al., Reference Cooney, Murphy and O'Shea2009; Anderberg and Berglund, Reference Anderberg and Berglund2010; Custers et al., Reference Custers, Westerhof, Kuin and Riksen-Walraven2010, Reference Custers, Kuin, Riksen-Walraven and Westerhof2011, Reference Custers, Westerhof, Kuin, Gerritsen and Riksen-Walraven2012; Knight et al., Reference Knight, Haslam and Haslam2010; Dunworth and Kirwan, Reference Dunworth and Kirwan2012; Morgan and Brazda, Reference Morgan and Brazda2013; Nåden et al., Reference Nåden, Rehnsfeldt, Råholm, Lindwall, Caspari, Aasgaard, Slettebø, Sæteren, Høy, Lillestø, Heggestad and Lohne2013; Gleibs et al., Reference Gleibs, Sonnenberg and Haslam2014; Hall et al., Reference Hall, Dodd and Higginson2014; Hillcoat-Nallétamby, Reference Hillcoat-Nallétamby2014; Johnson and Bibbo, Reference Johnson and Bibbo2014), irrespective of having executional autonomy (Hillcoat-Nallétamby, Reference Hillcoat-Nallétamby2014), to live the kind of life someone desires to live (Bolmsjö et al., Reference Bolmsjö, Sandman and Andersson2006; Walent and Kayser-Jones, Reference Walent and Kayser-Jones2008; Andresen et al., Reference Andresen, Runge, Hoff and Puggaard2009; Custers et al., Reference Custers, Westerhof, Kuin and Riksen-Walraven2010, Reference Custers, Kuin, Riksen-Walraven and Westerhof2011, Reference Custers, Westerhof, Kuin, Gerritsen and Riksen-Walraven2012; Knight et al., Reference Knight, Haslam and Haslam2010; Johnson and Bibbo, Reference Johnson and Bibbo2014; Sæteren et al., Reference Sæteren, Heggestad, Høy, Lillestø, Slettebø, Lohne, Råholm, Caspari, Rehnsfeldt, Lindwall, Aasgaard and Nåden2016; Walker and Paliadelis, Reference Walker and Paliadelis2016) in the face of diminishing social, physical and/or cognitive resources and dependency (Morgan and Brazda, Reference Morgan and Brazda2013; Sæteren et al., Reference Sæteren, Heggestad, Høy, Lillestø, Slettebø, Lohne, Råholm, Caspari, Rehnsfeldt, Lindwall, Aasgaard and Nåden2016), and it develops in relationships (Bolmsjö et al., Reference Bolmsjö, Sandman and Andersson2006; Knight et al., Reference Knight, Haslam and Haslam2010; Abma et al., Reference Abma, Bruijn, Kardol, Schols and Widdershoven2012; Baur and Abma, Reference Baur and Abma2012; Lagacé et al., Reference Lagacé, Tanguay, Lavallée, Laplante and Robichaud2012; Oosterveld-Vlug et al., Reference Oosterveld-Vlug, Pasman, van Gennip, Willems and Onwuteaka-Philipsen2013, Reference Oosterveld-Vlug, Pasman, van Gennip, Muller, Willems and Onwuteaka-Philipsen2014; Palacios-Ceña et al., Reference Palacios-Ceña, Losa-Iglesias, Cachón-Pérez, Gómez-Pérez, Gómez-Calero and Fernández-de-las-Peñas2013; Sæteren et al., Reference Sæteren, Heggestad, Høy, Lillestø, Slettebø, Lohne, Råholm, Caspari, Rehnsfeldt, Lindwall, Aasgaard and Nåden2016; Walker and Paliadelis, Reference Walker and Paliadelis2016).

Facilitators and barriers to autonomy of older adults with physical impairments in RCFs

The results of the literature review are organised into four themes of which characteristics of residents is the first theme. This theme is based on the included literature that provided rich information on the older adults themselves. The other themes are derived from the PCC framework: prerequisites of professional care-givers in RCFs, processes in the relationship between residents and professional care-givers, and the care environment (McCormack and McCance, Reference McCormack and McCance2017). Often the results reveal an ambiguity: aspects can either be facilitators or barriers. These will be elaborated on below, starting with the resident characteristics.

Characteristics of residents: facilitators

First, psycho-social characteristics of residents were identified (Table 4). Visits from family and friends help older adults to experience a sense of continuity of the life they lived before moving into the RCF (Hillcoat-Nallétamby, Reference Hillcoat-Nallétamby2014). As a consequence of these visits, the valued roles they used to have for family and friends can be maintained. This offers a sense of belonging and autonomy (Hwang et al., Reference Hwang, Lin, Tung and Wu2006; Chao et al., Reference Chao, Lan, Tso, Chung, Neim and Clark2008; Walent and Kayser-Jones, Reference Walent and Kayser-Jones2008; Cooney et al., Reference Cooney, Murphy and O'Shea2009; Oosterveld-Vlug et al., Reference Oosterveld-Vlug, Pasman, van Gennip, Muller, Willems and Onwuteaka-Philipsen2014). If older adults have financial resources, possibilities are created to make decisions on spending money and having choice and control in their lives in RCF (Chao et al., Reference Chao, Lan, Tso, Chung, Neim and Clark2008; Gleibs et al., Reference Gleibs, Sonnenberg and Haslam2014; Hillcoat-Nallétamby, Reference Hillcoat-Nallétamby2014). The presence of meaningful activities can give control and social engagement. Through these activities, older adults can help each other and, as a result, have useful recognised roles (Danhauer et al., Reference Danhauer, Sorocco and Andrykowski2006; Walent and Kayser-Jones, Reference Walent and Kayser-Jones2008; Custers et al., Reference Custers, Westerhof, Kuin, Gerritsen and Riksen-Walraven2012; Gleibs et al., Reference Gleibs, Sonnenberg and Haslam2014; Hillcoat-Nallétamby, Reference Hillcoat-Nallétamby2014; Råholm et al., Reference Råholm, Lillestø, Lohne, Caspari, Sæteren, Heggestad, Aasgaard, Lindwall, Rehnsfeldt, Høy, Slettebø and Nåden2014).

Table 4. Characteristics of residents

Also, diverse intrapersonal characteristics are distinguished. Coping skills, which older adults developed earlier in their life history, lead to more control over the situation and autonomy (Hwang et al., Reference Hwang, Lin, Tung and Wu2006; Curtiss et al., Reference Curtiss, Hayslip and Dolan2007; Cooney et al., Reference Cooney, Murphy and O'Shea2009; Anderberg and Berglund, Reference Anderberg and Berglund2010; Custers et al., Reference Custers, Westerhof, Kuin and Riksen-Walraven2010; Brandburg et al., Reference Brandburg, Symes, Mastel-Smith, Hersch and Walsh2013; Oosterveld-Vlug et al., Reference Oosterveld-Vlug, Pasman, van Gennip, Willems and Onwuteaka-Philipsen2013, Reference Oosterveld-Vlug, Pasman, van Gennip, Muller, Willems and Onwuteaka-Philipsen2014; Donnelly and MacEntee, Reference Donnelly and MacEntee2016; Walker and Paliadelis, Reference Walker and Paliadelis2016). Relations with staff are important for exercising autonomy. In these relationships, older adults’ need to be regarded as worthwhile persons can be fulfilled. Especially when residents lack family and friends who can act as advocates, relations with staff become more important (Chao et al., Reference Chao, Lan, Tso, Chung, Neim and Clark2008; Walent and Kayser-Jones, Reference Walent and Kayser-Jones2008; Oosterveld-Vlug et al., Reference Oosterveld-Vlug, Pasman, van Gennip, Willems and Onwuteaka-Philipsen2013, Reference Oosterveld-Vlug, Pasman, van Gennip, Muller, Willems and Onwuteaka-Philipsen2014; Gleibs et al., Reference Gleibs, Sonnenberg and Haslam2014; Hillcoat-Nallétamby, Reference Hillcoat-Nallétamby2014). The possibility of deciding themselves about moving into the facility seems to have a positive impact on the feeling of autonomy and control (Chao et al., Reference Chao, Lan, Tso, Chung, Neim and Clark2008; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Simpson and Froggatt2013; Morgan and Brazda, Reference Morgan and Brazda2013; Johnson and Bibbo, Reference Johnson and Bibbo2014).

The last characteristic of the residents is the level of physical functioning. A higher level results in more control and choice in activities. Also, there is a higher use of living and other spaces in the RCF. In addition, there are more possibilities for going out (Hwang et al., Reference Hwang, Lin, Tung and Wu2006; Chao et al., Reference Chao, Lan, Tso, Chung, Neim and Clark2008; Oosterveld-Vlug et al., Reference Oosterveld-Vlug, Pasman, van Gennip, Willems and Onwuteaka-Philipsen2013; Hillcoat-Nallétamby, Reference Hillcoat-Nallétamby2014).

Characteristics of residents: barriers

As said before, the aspects reveal an ambiguity, they can either be facilitator or barrier. The barriers are now given for the same aspects as above.

Psycho-social characteristics were identified, such as the absence of family and friends. In addition, being over-helped by others or receiving incongruent support are barriers to autonomy (Walent and Kayser-Jones, Reference Walent and Kayser-Jones2008; Morgan and Brazda, Reference Morgan and Brazda2013; Oosterveld-Vlug et al., Reference Oosterveld-Vlug, Pasman, van Gennip, Muller, Willems and Onwuteaka-Philipsen2014). If older adults do not have family and friends, they have to rely on staff or other residents for attention and help. Often older adults hesitate to state their wishes and needs. They suppose that staff are too busy. Sometimes older adults assume that complaining or asking for help will have a negative effect on the care they receive (Bolmsjö et al., Reference Bolmsjö, Sandman and Andersson2006; Hellström and Sarvimäki, Reference Hellström and Sarvimäki2007; Walent and Kayser-Jones, Reference Walent and Kayser-Jones2008; Cooney et al., Reference Cooney, Murphy and O'Shea2009; Lagacé et al., Reference Lagacé, Tanguay, Lavallée, Laplante and Robichaud2012; Morgan and Brazda, Reference Morgan and Brazda2013; Donnelly and MacEntee, Reference Donnelly and MacEntee2016).

Barriers in the intrapersonal characteristics, such as being unable to participate in the decision-making process of moving into the RCF, affect autonomy negatively (Chao et al., Reference Chao, Lan, Tso, Chung, Neim and Clark2008; Cooney et al., Reference Cooney, Murphy and O'Shea2009; Johnson and Bibbo, Reference Johnson and Bibbo2014; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Simpson and Froggatt2013). Furthermore, shared decision-making is not taken for granted, because rules and time schedules are often accepted by older adults (Hellström and Sarvimäki, Reference Hellström and Sarvimäki2007; Chao et al., Reference Chao, Lan, Tso, Chung, Neim and Clark2008; Walent and Kayser-Jones, Reference Walent and Kayser-Jones2008; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Simpson and Froggatt2013; Morgan and Brazda, Reference Morgan and Brazda2013; Johnson and Bibbo, Reference Johnson and Bibbo2014; Donnelly and MacEntee, Reference Donnelly and MacEntee2016; Sæteren et al., Reference Sæteren, Heggestad, Høy, Lillestø, Slettebø, Lohne, Råholm, Caspari, Rehnsfeldt, Lindwall, Aasgaard and Nåden2016; Walker and Paliadelis, Reference Walker and Paliadelis2016).

In physical functioning, as the last characteristic of residents, barriers are also found. Immobility and a diminished ability to communicate might act as barriers. A lack of energy can interfere with residents being able to live the lives they want to live (Hellström and Sarvimäki, Reference Hellström and Sarvimäki2007; Walent and Kayser-Jones, Reference Walent and Kayser-Jones2008; Oosterveld-Vlug et al., Reference Oosterveld-Vlug, Pasman, van Gennip, Willems and Onwuteaka-Philipsen2013, Reference Oosterveld-Vlug, Pasman, van Gennip, Muller, Willems and Onwuteaka-Philipsen2014; Gleibs et al., Reference Gleibs, Sonnenberg and Haslam2014).

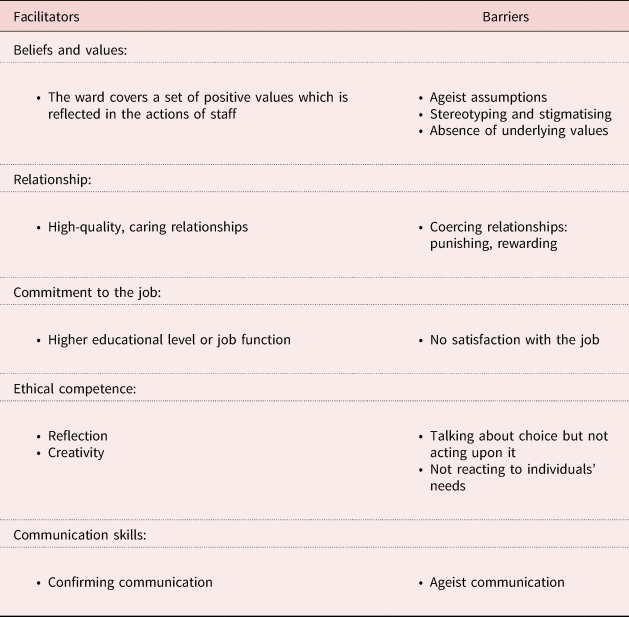

Prerequisites of professional care-givers in RCFs: facilitators

The second theme used to organise the results is the prerequisites of professional care-givers in RCFs (Table 5). The awareness of beliefs and values is established as prerequisite. Staff who are able to provide good professional care and are able to build high-quality relationships with residents help to preserve autonomy. So do staff who are able to treat residents with respect. The ability to take care of the physical appearance of residents also enhances autonomy (Custers et al., Reference Custers, Kuin, Riksen-Walraven and Westerhof2011; Oosterveld-Vlug et al., Reference Oosterveld-Vlug, Pasman, van Gennip, Muller, Willems and Onwuteaka-Philipsen2014; Råholm et al., Reference Råholm, Lillestø, Lohne, Caspari, Sæteren, Heggestad, Aasgaard, Lindwall, Rehnsfeldt, Høy, Slettebø and Nåden2014).

Table 5. Prerequisites of professional care-givers in residential care facilities

More highly educated nurses, and nurses in higher positions, seem to be more capable of supporting autonomy. They are more reflective in their attitude and have fewer ageist assumptions (Dunworth and Kirwan, Reference Dunworth and Kirwan2012).

Also, ethical competence and creativity of the staff are seen as facilitating autonomy (Bolmsjö et al., Reference Bolmsjö, Sandman and Andersson2006; Hall et al., Reference Hall, Dodd and Higginson2014).

Prerequisites of professional care-givers in RCFs: barriers

Barriers are also seen in the prerequisites. Dissatisfaction with the job and lack of ethical competence are barriers to autonomy. Negative beliefs and values such as ageist assumptions in staff, expressed in ageist communication and adverse relationships, are also barriers to autonomy (Bolmsjö et al., Reference Bolmsjö, Sandman and Andersson2006; Dunworth and Kirwan, Reference Dunworth and Kirwan2012; Gleibs et al., Reference Gleibs, Sonnenberg and Haslam2014; Hall et al., Reference Hall, Dodd and Higginson2014). An example of unethical behaviour in staff is seen when tables in the dining rooms are allocated as a punishment or reward for certain behaviours of older adults, thus leaving residents no choice of dinner companions (Palacios-Ceña et al., Reference Palacios-Ceña, Losa-Iglesias, Cachón-Pérez, Gómez-Pérez, Gómez-Calero and Fernández-de-las-Peñas2013). Another threat to autonomy is undignified care, like forced-feeding situations (Nåden et al., Reference Nåden, Rehnsfeldt, Råholm, Lindwall, Caspari, Aasgaard, Slettebø, Sæteren, Høy, Lillestø, Heggestad and Lohne2013).

Often encounters between staff and residents are scarce and show a lack of reciprocity. The last aspect in this theme is that staff seem unable to identify the underlying messages in the communication. This can lead to an unfulfilled desire for autonomy (Bolmsjö et al., Reference Bolmsjö, Sandman and Andersson2006).

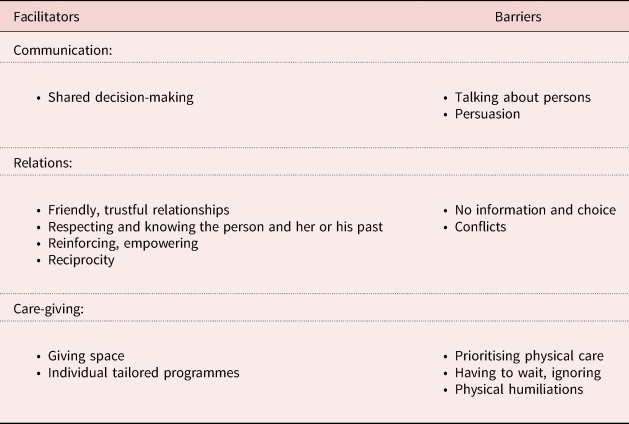

Processes in the relationship between residents and professional care-givers: facilitators

Communication is the first aspect that is distinguished in the processes between residents and care-givers (Table 6). Staff who have a good relationship with the older adults contribute to their need fulfilment. So do respectful communication and care for their physical appearance (Custers et al., Reference Custers, Westerhof, Kuin and Riksen-Walraven2010).

Table 6. Processes in the relation between residents and professional care-givers

Relations between residents and staff can reveal how diverse adaptive strategies are applied by older adults to have a life of their own in the RCF. Knowing and working with these individual strategies facilitates autonomy and assists older adults in dealing with problems (Andresen et al., Reference Andresen, Runge, Hoff and Puggaard2009; Brandburg et al., Reference Brandburg, Symes, Mastel-Smith, Hersch and Walsh2013).

Staff can find out what autonomy means for older adults by listening to life stories. These stories reflect the values of older adults in life, their personal identity and relations (Abma et al., Reference Abma, Bruijn, Kardol, Schols and Widdershoven2012). With an empowering strategy, involvement in care and shared goals can be realised and ownership is enhanced (Baur and Abma, Reference Baur and Abma2012; Sæteren et al., Reference Sæteren, Heggestad, Høy, Lillestø, Slettebø, Lohne, Råholm, Caspari, Rehnsfeldt, Lindwall, Aasgaard and Nåden2016).

Processes in the relationship between residents and professional care-givers: barriers

The lack of constructive communication can act as a barrier to autonomy. For example, when staff use routines, or impose activities of care or let older adults wait for help (Nåden et al., Reference Nåden, Rehnsfeldt, Råholm, Lindwall, Caspari, Aasgaard, Slettebø, Sæteren, Høy, Lillestø, Heggestad and Lohne2013; Palacios-Ceña et al., Reference Palacios-Ceña, Losa-Iglesias, Cachón-Pérez, Gómez-Pérez, Gómez-Calero and Fernández-de-las-Peñas2013; Oosterveld-Vlug et al., Reference Oosterveld-Vlug, Pasman, van Gennip, Muller, Willems and Onwuteaka-Philipsen2014; Donnelly and MacEntee, Reference Donnelly and MacEntee2016). The possibility of participating in decision-making can be hindered by a lack of information and choice (Hellström and Sarvimäki, Reference Hellström and Sarvimäki2007; Walent and Kayser-Jones, Reference Walent and Kayser-Jones2008). Furthermore, conflicts with staff might discourage older adults from expressing their wants and needs (Walent and Kayser-Jones, Reference Walent and Kayser-Jones2008; Lagacé et al., Reference Lagacé, Tanguay, Lavallée, Laplante and Robichaud2012; Hall et al., Reference Hall, Dodd and Higginson2014).

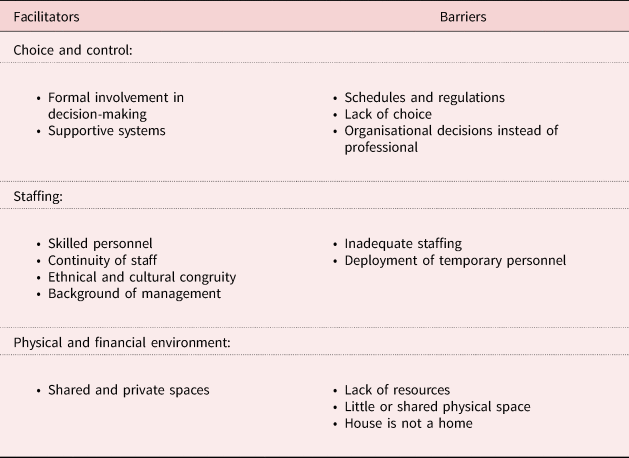

Care environment: facilitators

The last theme to organise the results is the care environment (Table 7). RCFs that have high levels of choice-enhancing policies and have adequate staff seem to increase the residents’ autonomy. Also, financial resources and a conforming physical outline seem to act as facilitators (Sikorska-Simmons, Reference Sikorska-Simmons2006; Walent and Kayser-Jones, Reference Walent and Kayser-Jones2008; Knight et al., Reference Knight, Haslam and Haslam2010). For example, the management can support the participation of older adults in organisational choices, such as selection of menu, gardening and social activities. This enhances the sense of mastery (Knight et al., Reference Knight, Davison, McCabe and Mellor2011; Baur and Abma, Reference Baur and Abma2012; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Simpson and Froggatt2013). Another example is the employment of skilled and permanent staff who share the same language, which facilitates autonomy (Walent and Kayser-Jones, Reference Walent and Kayser-Jones2008; Cooney et al., Reference Cooney, Murphy and O'Shea2009; Custers et al., Reference Custers, Kuin, Riksen-Walraven and Westerhof2011; Walker and Paliadelis, Reference Walker and Paliadelis2016; Dunworth and Kirwan, Reference Dunworth and Kirwan2012). A combination of appropriate shared and private spaces for older adults enhances choice, feelings of safety and participation (Chao et al., Reference Chao, Lan, Tso, Chung, Neim and Clark2008; Hall et al., Reference Hall, Dodd and Higginson2014; Hillcoat-Nallétamby, Reference Hillcoat-Nallétamby2014; Johnson and Bibbo, Reference Johnson and Bibbo2014).

Table 7. Care environment

Care environment: barriers

A lack of choice and control in daily life, such as the use of schedules, is found as a barrier. These schedules force older adults to fit their lives into routines, which might undermine autonomy. Also, routines for activities such as morning procedures, meals, washing, going to the toilet and bedtimes can act as barriers to autonomy (Curtiss et al., Reference Curtiss, Hayslip and Dolan2007; Andresen et al., Reference Andresen, Runge, Hoff and Puggaard2009; Hall et al., Reference Hall, Dodd and Higginson2014; Johnson and Bibbo, Reference Johnson and Bibbo2014).

Understaffing and employment of temporary employees can be barriers to autonomy. There is no time to get acquainted, to build relationships and to get to know the preferences of residents (Walent and Kayser-Jones, Reference Walent and Kayser-Jones2008; Hall et al., Reference Hall, Dodd and Higginson2014; Oosterveld-Vlug et al., Reference Oosterveld-Vlug, Pasman, van Gennip, Muller, Willems and Onwuteaka-Philipsen2014).

Shortages in resources due to directives and political decisions is one of the causes of understaffing. This affects autonomy because there are fewer staff to respond to older adults’ needs (Hellström and Sarvimäki, Reference Hellström and Sarvimäki2007; Gleibs et al., Reference Gleibs, Sonnenberg and Haslam2014). The physical outline of the building and decoration of the rooms influence the experience of feeling at home. RCFs that appear like a hospital have a non-confirming atmosphere (Cooney et al., Reference Cooney, Murphy and O'Shea2009; Lagacé et al., Reference Lagacé, Tanguay, Lavallée, Laplante and Robichaud2012; Nåden et al., Reference Nåden, Rehnsfeldt, Råholm, Lindwall, Caspari, Aasgaard, Slettebø, Sæteren, Høy, Lillestø, Heggestad and Lohne2013; Gleibs et al., Reference Gleibs, Sonnenberg and Haslam2014; Oosterveld-Vlug et al., Reference Oosterveld-Vlug, Pasman, van Gennip, Muller, Willems and Onwuteaka-Philipsen2014).

Discussion

The current literature review was executed to gain more insight into facilitators and barriers to autonomy of residents with physical impairments living in RCFs. Based on the literature search and the subsequent synthesis of the data of the included articles, the facilitators and barriers to autonomy were identified and organised. Three themes were based on the framework of PCP (McCormack and McCance, Reference McCormack and McCance2017). Particular aspects in the care environment act as barriers to autonomy. Relationships between staff and residents can either facilitate or inhibit autonomy, depending on the prerequisites of the care-givers and characteristics, e.g. coping skills, of the residents.

Although the framework includes elements of PCP, the care recipient her- or himself is not present in the model. In the current review, characteristics of residents that influence autonomy were determined. The theme ‘characteristics of residents’ is added to arrange the results of the older adults. The majority of the articles investigated this perspective, so a large set of attributes of residents that influence autonomy were distinguished.

Facilitators and barriers to autonomy can be allocated to elements of the PCP framework. The macro context, which contains aspects such as health policies and strategic frameworks, is not investigated in the included articles. The PCP framework seems to encompass all the distinguished influencing aspects for autonomy in the included articles. The culture change to more person-centred care can enhance autonomy. Realising a culture change in RCFs, however, is difficult with so many challenges to deal with (Donnelly and MacEntee, Reference Donnelly and MacEntee2016).

Based on the descriptions of the included articles, a description of autonomy was formulated. The authors established this description because it compiles the core elements of autonomy for older adults with physical impairments living in RCFs, as used in the included articles. Autonomy is described as a capacity to influence the environment (Knight et al., Reference Knight, Davison, McCabe and Mellor2011; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Simpson and Froggatt2013; Sæteren et al., Reference Sæteren, Heggestad, Høy, Lillestø, Slettebø, Lohne, Råholm, Caspari, Rehnsfeldt, Lindwall, Aasgaard and Nåden2016) and make decisions (Bolmsjö et al., Reference Bolmsjö, Sandman and Andersson2006; Hwang et al., Reference Hwang, Lin, Tung and Wu2006; Sikorska-Simmons, Reference Sikorska-Simmons2006; Hellström and Sarvimäki, Reference Hellström and Sarvimäki2007; Walent and Kayser-Jones, Reference Walent and Kayser-Jones2008; Andresen et al., Reference Andresen, Runge, Hoff and Puggaard2009; Cooney et al., Reference Cooney, Murphy and O'Shea2009; Anderberg and Berglund, Reference Anderberg and Berglund2010; Custers et al., Reference Custers, Westerhof, Kuin and Riksen-Walraven2010, Reference Custers, Kuin, Riksen-Walraven and Westerhof2011, Reference Custers, Westerhof, Kuin, Gerritsen and Riksen-Walraven2012; Knight et al., Reference Knight, Haslam and Haslam2010; Dunworth and Kirwan, Reference Dunworth and Kirwan2012; Morgan and Brazda, Reference Morgan and Brazda2013; Nåden et al., Reference Nåden, Rehnsfeldt, Råholm, Lindwall, Caspari, Aasgaard, Slettebø, Sæteren, Høy, Lillestø, Heggestad and Lohne2013; Gleibs et al., Reference Gleibs, Sonnenberg and Haslam2014; Hall et al., Reference Hall, Dodd and Higginson2014; Hillcoat-Nallétamby, Reference Hillcoat-Nallétamby2014; Johnson and Bibbo, Reference Johnson and Bibbo2014), irrespective of having executional autonomy (Hillcoat-Nallétamby, Reference Hillcoat-Nallétamby2014), to live the kind of life someone desires to live (Bolmsjö et al., Reference Bolmsjö, Sandman and Andersson2006; Walent and Kayser-Jones, Reference Walent and Kayser-Jones2008; Andresen et al., Reference Andresen, Runge, Hoff and Puggaard2009; Custers et al., Reference Custers, Westerhof, Kuin and Riksen-Walraven2010, Reference Custers, Kuin, Riksen-Walraven and Westerhof2011, Reference Custers, Westerhof, Kuin, Gerritsen and Riksen-Walraven2012; Knight et al., Reference Knight, Haslam and Haslam2010; Johnson and Bibbo, Reference Johnson and Bibbo2014; Sæteren et al., Reference Sæteren, Heggestad, Høy, Lillestø, Slettebø, Lohne, Råholm, Caspari, Rehnsfeldt, Lindwall, Aasgaard and Nåden2016; Walker and Paliadelis, Reference Walker and Paliadelis2016) in the face of diminishing social, physical and/or cognitive resources and dependency (Morgan and Brazda, Reference Morgan and Brazda2013; Sæteren et al., Reference Sæteren, Heggestad, Høy, Lillestø, Slettebø, Lohne, Råholm, Caspari, Rehnsfeldt, Lindwall, Aasgaard and Nåden2016), and it develops in relationships (Bolmsjö et al., Reference Bolmsjö, Sandman and Andersson2006; Knight et al., Reference Knight, Haslam and Haslam2010; Abma et al., Reference Abma, Bruijn, Kardol, Schols and Widdershoven2012; Baur and Abma, Reference Baur and Abma2012; Lagacé et al., Reference Lagacé, Tanguay, Lavallée, Laplante and Robichaud2012; Oosterveld-Vlug et al., Reference Oosterveld-Vlug, Pasman, van Gennip, Willems and Onwuteaka-Philipsen2013, Reference Oosterveld-Vlug, Pasman, van Gennip, Muller, Willems and Onwuteaka-Philipsen2014; Palacios-Ceña et al., Reference Palacios-Ceña, Losa-Iglesias, Cachón-Pérez, Gómez-Pérez, Gómez-Calero and Fernández-de-las-Peñas2013; Sæteren et al., Reference Sæteren, Heggestad, Høy, Lillestø, Slettebø, Lohne, Råholm, Caspari, Rehnsfeldt, Lindwall, Aasgaard and Nåden2016; Walker and Paliadelis, Reference Walker and Paliadelis2016).

Based on the included articles, the description focuses on decisional and relational autonomy. This might be explained because the literature search was performed for physically impaired older adults living in RCFs. These residents are generally able to make choices, but physical impairments can obstruct the execution of the decisions taken. They often need practical help from others to carry out their decisions. Also, the relational aspect was prominent in the included articles, which can be related to the fact that living in an RCF means living with other residents and staff, and thus in relation to others.

The aspect of forced autonomy, using force to make decisions and act upon them independently, was not present in the included articles. However, paternalism was present: making choices for persons who are able to make decisions on their own.

Nonetheless, we found barriers to autonomy related to force, for example the forced use of services, such as eating, following regulations, transfer to the residential care, and transfer of tasks and responsibilities. Autonomy, in the included articles, is often hindered by care-givers and institutions, and is not forced upon residents (Hwang et al., Reference Hwang, Lin, Tung and Wu2006; Hellström and Sarvimäki, Reference Hellström and Sarvimäki2007; Knight et al., Reference Knight, Davison, McCabe and Mellor2011; Dunworth and Kirwan, Reference Dunworth and Kirwan2012; Lagacé et al., Reference Lagacé, Tanguay, Lavallée, Laplante and Robichaud2012; Oosterveld-Vlug et al., Reference Oosterveld-Vlug, Pasman, van Gennip, Muller, Willems and Onwuteaka-Philipsen2014).

Strengths

In this review, results from articles that focus on dignity, self-determination and autonomy are aggregated. The different positions in the relationships between the three concepts and their intertwined use in the included articles made it rewarding to merge all facilitators and barriers. As a result of the merging, the review offers a comprehensive overview of factors that influence autonomy of residents with physical impairments living in RCFs.

The execution of the systematic review by four of the five authors was established first independently and later through meetings to achieve a uniform procedure at the start of each stage of the selection, quality assessment and data extraction. The first author assessed all articles. Three of the co-authors reviewed a selection of the articles. At each stage of the selection process, consensus was reached about inclusion or exclusion of articles by means of bilateral discussions.

Limitations

A limitation in organising the results according to the PCP framework is that some of the included articles lack specific information, so the allocation of a facilitator or barrier can be difficult. For example, the framework makes a distinction between being prepared for the job (prerequisites) and delivering care (person-centred processes). However, there is not enough information in the included articles about preparation for the job or educational background. The consequence is that it is difficult to allocate results such as communication to either prerequisites (communication skills) or care processes (communication). The same can be said for building relationships (prerequisite) and relations (care processes). In that case, barriers and facilitators were allocated to both themes, so a repetition is seen.

In this study, the authors aimed to include residents with physical impairments. However, it cannot be certain that persons with dementia were totally excluded because of the lack of precise information about the assessment of mental status. The content of the articles, however, gives confidence that the research is not done on persons with moderate or severe dementia.

The same can be said for the inclusion of persons with an average age of 65 years. The authors screened the articles thoroughly to exclude studies on residents under 65 years. However, if some individuals under this age participated in the studies, the authors calculated the mean age. The mean in all these articles was 77 years or more. This mean of 77 was used as a rationale to include the article as describing residents above 65 years. For three included articles, the authors were not able to calculate a mean age because the individual ages of the participants were not given. However, an age range of 49–102 (Oosterveld-Vlug et al., Reference Oosterveld-Vlug, Pasman, van Gennip, Willems and Onwuteaka-Philipsen2013), 62–103, (Sæteren et al., Reference Sæteren, Heggestad, Høy, Lillestø, Slettebø, Lohne, Råholm, Caspari, Rehnsfeldt, Lindwall, Aasgaard and Nåden2016) and 60–100 (Lagacé et al., Reference Lagacé, Tanguay, Lavallée, Laplante and Robichaud2012) was provided for the participants of their studies. The subject of the articles gives us the assurance that the group had age-related impairments.

Implications for practice and science

The current review leads to a better understanding of autonomy-enhancing elements for residents with physical impairments in RCFs. Autonomy is a broad, complex, multifaceted and relational concept that can be influenced by many factors in various ways. The results have implications for practice for both residents and care-givers, because they offer possibilities to preserve and enhance autonomy. The knowledge of facilitators and barriers established in this review can be used in the education of current and future nurses or other care personnel to make them aware of how to enhance autonomy. Based on the results in all four themes, RCFs can systematically develop autonomy-enhancing practices.

Scientifically, this study creates new knowledge and provides an actual overview on autonomy for older adults with physical impairments in RCFs and how to support autonomy. The results accentuate the influence of multiple aspects to achieve autonomy in RCFs.

More empirical research should be done on autonomy in practice. What significance does autonomy have for residents and staff and when is autonomy (not) enhanced or perhaps forced? Do we recognise (parts of) the description of autonomy in daily care practice? Because autonomy is a complex, relational and dynamic concept, it can best be investigated through observational methods that examine the perspectives of residents and care-givers. Shadowing is a method that can be used in an environment where autonomy is manifested, e.g. in RCFs (van der Meide et al., Reference van der Meide, Olthuis and Leget2015). Research can give insight into how factors established in this review interrelate and how they are expressed in the care process. It is advisable to investigate dimensions of the concept of autonomy other than executional and decisional autonomy which dominate in the results of this systematic review. It is possible that important aspects of autonomy – e.g. the relational aspect of autonomy – are getting less attention or can be overlooked if further research restricts itself to this polarity. More attention should also be paid to the facilitators and barriers in the macro context. RCFs are strongly dependent on government health policies and funding to achieve autonomy-enhancing practices.

Furthermore, the knowledge can be used in participatory transformational action research. Action groups with different stakeholders in RCFs can experiment with actions to strengthen autonomy. In this way, the perspectives of residents, care-givers and organisations can be studied in relation to each other. Supportive practices for autonomy can be identified and examined by means of this bottom-up development.

Author contributions

JvL performed the literature search and selection, assessed the quality of the selected articles, extracted data and constructed the tables. KL, IdR and BJ selected the articles, assessed the quality of the selected articles and extracted data. All the authors, including MJ, interpreted the findings and were involved in the drafting and revisions of the manuscript. They approved the publication of the article.

Financial support

This work was supported by De Wever, a care organisation in Tilburg. De Wever had no role in the research.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

Not applicable for a literature review.