Optimal nutrition in paediatric intensive care (PIC) plays an important role in improving patient outcomes through sustaining organ function and preventing dysfunction of the cardiovascular, respiratory and immune systems(Reference Irving, Simone and Hicks1, Reference Briassoulis, Zavras and Hatzis2). Enteral nutrition (EN) is preferential to parenteral nutrition in critically ill patients for reasons including maintaining gut integrity and reducing the risk of infection(Reference Simpson and Doig3). A recent guideline found that EN in PIC was interrupted in nearly one-third of patients due to intolerance to feeds (high gastric residual volume (GRV), emesis or diarrhoea), blocked/misplaced feeding tubes or medical procedures requiring fasting(Reference Mehta, McAleer and Hamilton4). Many of these interruptions were avoidable and impacted on patient outcomes(Reference Mehta, McAleer and Hamilton4). Other factors that impact on EN include fluid restriction and feed intolerance related to haemodynamic instability and inappropriate feed stoppage due to poor adherence to guidelines(Reference Rogers, Gilbertson and Heine5, Reference Tume, Latten and Darbyshire6). It was decided, therefore, to describe the present knowledge of healthcare professionals and the practices surrounding enteral feeding in the UK and Irish PIC units (PICU) and propose recommendations for practice and research.

Methods

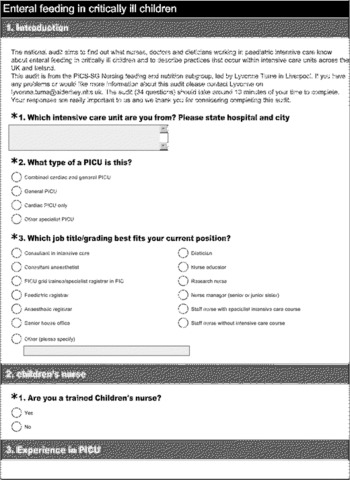

The present cross-sectional (thirty-four item, predominantly close-ended) survey was developed to describe the present knowledge of healthcare professionals and the practices surrounding enteral feeding in the UK and Irish PICU (see Appendix). The Paediatric Intensive Care Society Study Group's (PICS-SG) group lead was approached to determine if ethical approval was required, but they determined that it was not required for the present study. The study was approved by the PICS-SG and registered as an audit with the National Health Service (NHS) Trust.

No suitable and validated pre-existing tool was identified; hence, the survey team (the three authors and a consultant nurse (Andy Darbyshire) from a PICU) developed the survey using an iterative process of question development and refinement. The intention of the present survey was not to develop a fully validated tool, but to create a tool with sufficient robustness. The processes undertaken aimed to provide a level of face and content validity. The tool was initially developed as a paper-based pilot tool, with input and review from the Trust's Research and Review Committee; this thirty-seven-item tool was then piloted in a single centre with 118 staff (64 % response rate). Following this pilot study, three questions were removed, the method of determining energy requirements (as so few medical or nursing staff knew this), a question about laxative use that was problematic and a question about dietetic referral, as these were not felt to specifically address the study aims.

The final version was then transferred across to an electronic format to be sent out nationally. The question domains and specific questions were built on an extensive review of the literature and experiential knowledge of the practice. The survey was designed to be user friendly, unambiguous and to minimise the time burden for completion. This meant that careful decisions were taken about the breadth and depth of the survey, resulting in some potential valuable domains not being addressed (e.g. dietitians' workload in PICU and specific prescribing practices). The survey was designed using single response answers, multiple response answers, ranked answers and free text, as appropriate to specific questions. Careful instructions about how to complete the survey were provided. This cross-sectional, thirty-four-item electronic survey (on SurveyMonkey®; www.surveymonkey.com) was sent out to all PICU listed in the Paediatric Intensive Care Audit Network (PICANET) database (http://www.picanet.org.uk). The link to this e-survey was emailed to all lead consultants, lead nurses and all members of the PICS-SG in November 2010 and asked to forward this survey link to up to ten members (various disciplines and experience) of their team.

The acceptable unit response rate was set at 70 %. Two reminders were sent if a unit had not responded. As the study was exploratory, most results were analysed descriptively and involved the differences in enteral feeding practices across the PICU. Inferential data analysis was undertaken in SPSS v15 (SPSS, Inc.) by L. T. and examined; wherever possible, the difference between nurses', doctors' and dietitian's views of enteral feeding were compared using the χ2 test (a P value < 0·05 was considered significant). Most results are presented by individual responses (as per the aim of the survey), but where appropriate, unit responses are presented. Percentages do not always add up to 100 % (e.g. where the staff members were asked to identify the ‘top three factors’).

Results

The overall PICU response rate from the e-survey was 90 % (27/30 PICU; 108 individual responses, 1–21 responses per unit, mean unit response rate 3).

Demographics of the respondents

Of the PICU staff responding to the survey, 41 % (11/27) were from combined cardiac and general PICU, 48 % (13/27) were from general PICU, 7 % (2/27) were from cardiac intensive care units (ICU) and 5 % (1/27) from other specialist ICU. There was a cross-section of respondents (Table 1; 69 % (74/108) had over 5 years PIC experience). The overall breakdown of the professional groups was: 59 % (n 64) nursing staff (most were children's nurses); 27 % (n 29) medical staff; 13 % (n 14) dietitians; and 1 % (n 1) physician assistants.

Table 1 Breakdown of respondents (n 108) (Number of respondents and percentages)

PIC, paediatric intensive care; ICU, intensive care unit.

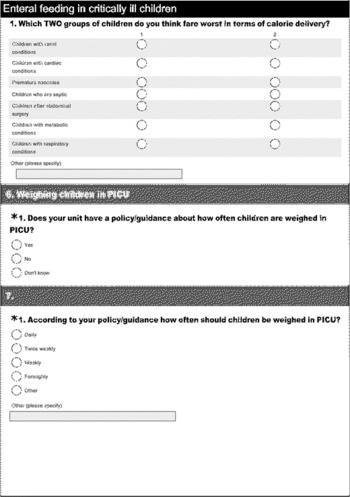

Feeding on paediatric intensive care units

Most units (96 %; 26/27) had some written guidance (although brief and generic) on EN; and 85 % (88/103) of staff, across all professional groups (P= 0·672), thought that guidelines helped to improve energy delivery in the PICU. There was a perception by respondents that two groups of critically ill children fared worst in terms of energy delivery; these were children with cardiac conditions (77·6 %) and children after abdominal surgery (61·5 %). A number of contraindications to enteral feeding in PIC were cited with suspected necrotising enterocolitis (NEC), the most common contraindication to EN (88 %, 91/104), followed by post-operative abdominal surgery (46 %, 48/104), high serum lactates (11 %, 11/104) and post-operative coarctation of the aorta (11 %, 11/104) (Fig. 1). In terms of assessing weight gain in critically ill children, less than one-half of respondents (29·9 %) said their unit had a policy for how often children were weighed, and one-third of respondents (37·5 %) said this was weekly, with 31·3 % saying twice weekly. However, when asked when they thought children in a PICU should be weighed, over one-half (51·9 %) said when the child had been on the PICU for more than 1 week.

Fig. 1 Perceived contraindications for enteral feeding, in response to the question ‘Which of the following conditions do you think are absolute contraindications to enteral feeding?’. (A colour version of this figure can be found online at http://www.journals.cambridge.org/bjn).

When asked about how much of the child's prescribed energy intake they actually received, 70 % (75/107) of the staff stated that, on average, they thought children got less than 60 % of their prescribed energy intake and 30 % (32/107) of them stated they received more than 60 % of their required energy. This did not differ by professional group (P= 0·489). Fluid-restrictive policies (60 %), the child just being ‘too ill’ to feed (17 %), surgical post-operative orders (16 %), nursing staff being too slow in starting feeds (7 %), frequent procedures requiring fasting (7 %) and haemodynamic instability (7 %) were key factors identified in poor energy delivery. In terms of starting and stopping enteral feeds, 45 % (45/101) of the respondents said there was ‘no target start time’ for enteral feeding; 25 % (24/101) stated ‘just when the child was stable enough’ (see Fig. 2); and 24 % (24/101) of the respondents stated their guidelines were to start feeds within 4–6 h of admission. Across all professional groups (P= 0·615), the highest ranking reason to stop EN was when NEC was suspected (66 %, 57/87), followed by high GRV (32 %, 19/60) or gastrointestinal bleeding (29 %, 10/35). The top three signs used to determine feed tolerance were the amount of GRV, the absence of vomiting, followed by no abdominal distension and bowel sounds. All three professional groups placed a similar level of importance on GRV as an indicator to stop feeds (P= 0·173).

Fig. 2 Starting times for enteral feeds in the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU), in response to the question ‘Does your unit have a target time for starting enteral feeds after PICU admission? and if so what is this?’. (A colour version of this figure can be found online at http://www.journals.cambridge.org/bjn).

Gastric residual volumes

What constituted an ‘acceptable’ level of GRV varied markedly (50 different and subjective responses) ranging from 3 (47 %) to 10 ml/kg (11 %) for a 5 kg infant. Broadly, it was felt that GRV had to be calculated by a percentage of what had been fed (range 25–100 %) or how many hours worth of feed remained (range 3 to >6 h worth of feed) or an amount in ml/kg (responses ranged from 4 to 5 ml/kg over a 4-h period). There were no significant differences between professional groups (P= 0·903). The differences were more pronounced for an acceptable GRV in a 50 kg adolescent (range 100 ml (1 %; 0·5 ml/kg) to 400 ml (12 %; 8 ml/kg)). For an adolescent, the majority expressed the acceptable level as ‘percentage of feed given’ (range >25 to >70 % of feed). There were no differences between professional groups (P= 0·174). In terms of patient-related factors that affect GRV, 63 % (54/86) of respondents said the site of the feeding tube was ‘most important’, followed by whether continuous feeds were used and the amount of gastric juice the patient produced. In terms of technical factors, 66 % (52/79) said that the position of the feeding tube would be the most important factor affecting aspirate volume obtained. Migration of the feeding tube and other factors such as syringe size, type of feeding tube and nurse's technique were rated less important in affecting the amount of aspirate obtained. For both technical- and patient-related factors, nurses placed significantly more importance on the site of the feeding tube than did doctors or dietitians (P= 0·021).

Improving feed tolerance and fasting for procedures

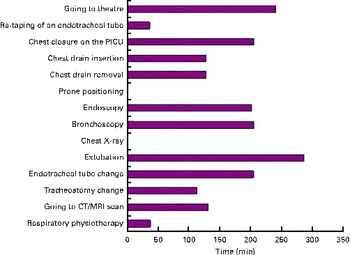

The first action that the respondents (77 %, 48/52) would use to improve feed tolerance would be to stop the feeds for a while and re-check the aspirate, followed by changing the continuous feeds and then starting a pro-kinetic agent. There was no difference between professional groups (P= 0·610). A total of 42 % (24/57) of the respondents stated that they would change from bolus to continuous feeds if the child was very ill, 32 % (30/93) stated that their standard regimen used continuous feeds. Significantly more nurses would consider changing to continuous feeds (P= 0·019) if the child was not tolerating bolus feeds. Most respondents (82 %) said they always or sometimes used pro-kinetic agents. In all, 86 % (87/101) stated that they used trophic feeds, although each provided a different response about what constituted trophic feeds. The most common definition of trophic feed was between 2 and 15 ml/kg every 1–3 h or 2–10 ml/h. When asked about how early would parenteral nutrition be considered after feed intolerance, 34 % of respondents stated between 48 and 72 h; 33 % said between 24 and 48 h; 19 % saying more than 72 h; 2 % stating < 24 h; and 11 % did not know. Although we did not specifically ask about naso-jejunal (or post-pyloric) feeding, a number of answers alluded to considering this, with a clinician from one unit claiming it was their default method to feed enterally. Fasting children for procedures on PIC was a significant problem and there was considerable variation across respondents about which procedures required fasting (Fig. 3) and the duration of fasting required (mean fasting time, Fig. 4). All staff fasted children for extubation and for theatre.

Fig. 3 Pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) procedures that patients were fasted for, in response to the question ‘For an average intubated and naso-gastrically fed child on the PICU which of these procedures would you fast the child before? Please tick all that apply’. CT, Computerised tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging. (A colour version of this figure can be found online at http://www.journals.cambridge.org/bjn).

Fig. 4 Mean total fasting (before and after), in response to the question ‘For the procedures you indicated previously that you would fast the child for how long would they be fasted for? (minutes in total before and after the procedure)’. PICU, paediatric intensive care unit; CT, computerised tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging. (A colour version of this figure can be found online at http://www.journals.cambridge.org/bjn).

Discussion

To our knowledge, there have been no previous surveys of the UK and Irish paediatric ICU practices and staff views on enteral feeding. Previous surveys have primarily focused on adult intensive care nurses and found that practices regarding management of enteral feeding varied widely among nurses and that nursing practices alone may be contributing to underfeeding in critically ill patients(Reference Mateo7–Reference Hill, Nielsen and Lennard-Jones10). Four prospective cohort studies show that guidelines help improve energy delivery in the PICU(Reference Briassoulis, Zavras and Hatzis2, Reference Tume, Latten and Darbyshire6, Reference Petrillo-Albarano, Pettignano and Asfaw11). Most PICU had some written guidance on EN and most respondents (85 %) believed that guidelines helped improve energy delivery in the PICU. Most staff perceived that, on average, children in PICU got less than 60 % of their prescribed energy intake; this is consistent with the reported studies in critically ill children of energy delivery ranging from 37 to 60 % of the child's predicted requirements(Reference Rogers, Gilbertson and Heine5, Reference Tume, Latten and Darbyshire6, Reference deNeef, Geukers and Dral12, Reference Taylor, Preedy and Baker13).

In terms of absolute contraindications to EN in PIC, suspected NEC was the most prominent with immediate bowel rest as a key treatment strategy in the management of suspected NEC(Reference Lee and Polin14). Although 12 % of respondents' proposed high serum lactates as an absolute contraindication, PIC evidence does not support this. However, in adult patients (n 128), a high admission serum lactate was highly predictive of gastrointestinal dysfunction(Reference Cresci and Cue15). Coarctation of the aorta reduces systemic and mesenteric blood flow pre-operatively and mesenteric blood flow is also altered post-operatively(Reference Ho and Moss16). Although 12 % of respondents stated coarctation of the aorta as a contraindication, there is only one published case of NEC in a neonate where coarctation of the aorta was identified(Reference Hasegawa, Yoshioka and Sasaki17). Most of these perceived contraindications seem to be based on risk aversion strategies.

In relation to the initiation of enteral feeds, although 45 % of respondents had no specific target start time to start EN, 24 % stated they would start within 4–6 h of PICU admission. A systematic review of early enteral feeding ( < 36 h after ICU admission) compared to late in critically ill adults showed that early enteral feeding was associated with significantly lower incidence of infections (P≤ 0·0006) and a reduced length of hospital stay (P= 0·004)(Reference Marik and Zaloga18). Another meta-analysis demonstrated that even earlier enteral feeding ( < 24 h of ICU admission) reduced mortality in critically ill adults(Reference Doig, Heighes and Simpson19). Others have showed that early ( < 6 h after ICU admission) EN was possible and improved time to achieve energy goal; however, there is no evidence of the effect of early EN on outcomes in children(Reference Petrillo-Albarano, Pettignano and Asfaw11).

The concept of trophic feeding originated in feeding preterm infants and has demonstrated some benefits in them(Reference Burrin, Stoll and Jiang20–Reference McClure and Newell22). However, a Cochrane review could not recommend this practice(Reference Bombell and McGuire23). Despite the uncertainty about whether benefits seen in preterm neonates can be extrapolated to critically ill children, trophic feeding is widespread in PICU in the UK and Ireland. A total of 86 % of the respondents used trophic feeds. However, what was considered trophic varied considerably. The concept of early ‘trickle’ or ‘trophic’ feeds was recommended in the American Society for parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN) adult nutrition guidelines(Reference McClave, Martindale and Vanek24) and tested in a randomised controlled trial in ventilated adults with respiratory failure(Reference Rice, Mogan and Hays25). Limited evidence supports the theory and practicalities of trophic feed administration.

The GRV featured prominently in the decision to both stop EN and to determine feed tolerance, and was similar for all professional groups; however, evidence to support the use of GRV is problematic. The risk of potential aspiration of gastric contents is reported as high in critically ill patients and a major risk factor for the development of pneumonia(Reference Metheny, Clouse and Chang26). However, this level of risk is difficult to quantify. Multiple factors can affect the gastric emptying rate and thus an increase in GRV in PIC children(Reference Gonzalez27–Reference Fruhwald, Holzer and Metzler29). The direct measurement of gastric emptying is difficult in clinical practice; only one PICU in the UK measures gastric emptying time on all children. Additionally, the correlation between GRV and gastric emptying remains unclear(Reference Fruhwald, Holzer and Metzler29). The present results show both a large variation in what is considered an acceptable GRV and the variations in how GRV is measured across PICU. Given that, in PICU, the majority of children are aged < 12 months, then it is unsurprising that uncertainty increases when considering larger children and adolescents. Considerable debate occurs about the utility of GRV measurement in critically ill patients receiving EN. An adult study found that early EN without GRV monitoring improved the delivery of EN and did not increase vomiting or ventilator-associated pneumonia(Reference Poulard, Dimet and Martin-Lefevre30). These findings are supported by a further randomised controlled trial of 328 adults that found that a GRV of 500 ml was not associated with any adverse events or gastrointestinal complications(Reference Montejo, Minambres and Bordeje31). In measuring GRV, there is a presumption that the measured volume is accurate. However, various factors affect this, including the syringe size, the type and lumen size of the feeding tube, position of the patient and the feeding tube in the stomach and aspiration technique(Reference Gonzalez27, Reference Metheny32). Small lumen tubes, small size aspirating syringes and collapsible soft feeding tubes can all produce falsely low GRV, as can adherence of the tip of the tube to the gastric mucosa or positioning within the stomach where gastric fluid has not accumulated(Reference Gonzalez27, Reference Metheny32). The respondents appeared to be unaware of some of these factors when making decisions about the GRV. Technical factors affecting GRV (e.g. equipment used and nurse's technique) were rated less important in affecting the amount of aspirate obtained – implying a reduced awareness of these factors. For both patient and technical factors, nurses played significantly more importance on the site of the feeding tube, perhaps reflecting their core responsibility in confirming the tube placement.

Stopping feeds for a while and rechecking aspirate was the first course of action that respondents proposed, followed by changing the continuous feeds and then starting a pro-kinetic agent. Although the adult ASPEN guidelines recommend the use of pro-kinetic agents(Reference McClave, Martindale and Vanek24), a systematic review in neonates was unable to make any recommendations, and the present ASPEN paediatric guidelines do not recommend their use(Reference Mehta, McAleer and Hamilton4). Despite this, 82 % of respondents said they sometimes or always used pro-kinetic agents. Significantly more nurses would consider changing to continuous feeds (P= 0·019) if the child was not tolerating bolus feeds. Furthermore, just over one-half of our respondents said their default method to start EN was continuous nasogastric feeds. No studies have ever shown continuous feeds to be superior to intermittent feeds in terms of GRV. Only one randomised controlled trial (n 45) has examined continuous v. bolus feeds in PICU patients, and this showed no differences in GRV between the two methods(Reference Horn, Chaboyer and Schluter33). Studies in preterm infants also found no difference in GRV, although they showed a higher GRV in the continuously fed group(Reference Kocan and Hickisch34–Reference Schanler, Schulman and Lau37).

The critical care literature (adult, child and neonatal) frequently cites feed interruptions as a major problem for reducing energy delivery in ICU(Reference Mehta38). A small study revealed that feed interruptions for procedures requiring fasting occurred in 43 % children in one 24-h period (mean fasting time was 8·9 h)(Reference Tume, Latten and Darbyshire6). This is consistent with other paediatric studies(Reference Rogers, Gilbertson and Heine5) and adult ICU studies(Reference Morgan, Dickerson and Alexander39, Reference O'Meara, Mireles-Cabodevila and Frame40). The present study showed considerable variation across respondents for both the procedures that children were fasted for and the mean fasting time. Critically ill children are likely to have delayed gastric emptying, and the mean fasting time in the present survey before extubation or anaesthesia was 6 h, which seems reasonable. Although neither the procedures fasted for nor the duration of fasting are based on any evidence, the degree to which these are applied within a unit does significantly make an impact on the amount of enteral feed delivered and reflects a unit's risk aversion strategy.

Limitations

Because the unit response rate varied from 1 to 21 (mean 3) responses per unit, some larger units may be over-represented in the results. In addition, our technique of secondary invitation of respondents by selected lead individuals within a unit could introduce selection bias and we acknowledge this; however, guidance was provided to them to circulate to a mix of professionals with varying degrees of experience and education. There was a predominance of nursing respondents (59 %) and, although this arguably over-represents one disciplinary perspective, it does reflect the reality of staff mix in PICU. Again, because of our design, we do not know details about non-responders, and this again may introduce bias in our sample. The small numbers of non-PIC-trained staff (both doctors and nurses) did not allow the comparison between PIC education of staff and responses, and the small cell frequencies in some analyses was a limitation when undertaking the χ2 test. Given the issue of GRV, in retrospect, perhaps we could have asked whether GRV was discarded or returned, and it would also have been interesting to ask about the use of post-pyloric feeding, which we did not. The large number of free comments provided by respondents made quantitative analysis challenging, but reflects the PIC experience of these clinicians, the variability of patient conditions and ages and gives insight into the range of views. However, the survey's strengths are its multi-disciplinarity and the 90 % response rate from across the UK and Ireland.

Recommendations for practice and research

Practice recommendations include improving the standardisation and consistency for EN. Agreed fasting times for regular interventional procedures on PICU would improve feeding times, as would an agreed method of measuring GRV and defining an acceptable volume. The results of this survey clearly illuminate the diversity and uncertainty about the management of EN in PIC. The authors propose that the present study provides a robust first step in identifying the core areas of concern and inconsistency and that the development of national consensus guidelines for EN in PIC is warranted. Such guidelines would need to be built upon both robust evidence and the expert consensus from across the UK with the potential for the guidelines to use a traffic light system (red – contraindicated, orange – unsure, green – acceptable) to assist in decision making. Enhanced education about factors affecting GRV should be provided to the PIC staff. A national multi-disciplinary PIC EN research and advisory group should be established to promote more collaborative research and improve nutrition in PIC across the UK and Ireland. In terms of research priorities, the most accurate method for the measurement of GRV, determining the risk of aspiration in critically ill children, its relationship to GRV and whether this is this the same across all age profiles are key priorities. Other priorities include evidence for measuring gastric emptying time in critically ill children and whether this affects nutritional outcomes (feed tolerance and energy delivery) and the role of the dietitian in clinical feeding problems in the PICU.

Conclusions

The present survey has highlighted the variability of the present enteral feeding practices across the UK and Ireland, particularly with regard to the use of GRV and fasting for procedures. These findings are similar to other published work internationally in terms of practice variations, but highlight a number of recommendations for both practice and research, which the PIC and dietetic communities should act on.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank all the PICU staff in the UK and Ireland who participated in the present survey and PICS-SG for supporting this project and Mr Andy Darbyshire for his involvement in this project. The author's contributions are as follows: L. T., B. C., L. L. designed the study; L. T. collected and analysed the data; L. T., B. C., L. L. wrote the manuscript. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix