How does a good official become corrupt in China? Good officials, as we all know, are honest and righteous. However, after a period of time in office, some begin to take bribes and steal public resources. How does this happen? Exploring and understanding the mechanisms behind this interaction process is crucial, especially for China, the world's second largest and still fast-growing economy.

Transparency International found that among the 168 countries evaluated for its 2015 Corruption Perception Index (CPI), two-thirds scored less than 50 out of a perfect score of 100% transparency. Corruption is a particularly troubling phenomenon in developing countries because of its large negative impact (Cameron, Chaudhuri, Erkal, & Gangadharan, Reference Cameron, Chaudhuri, Erkal and Gangadharan2009). It has also been a prominent political and social problem in China during its recent social transformation period (Deng, Zhang, & Leverentz, Reference Deng, Zhang and Leverentz2010; He, Reference He2000; Ting, Reference Ting1997; Wedeman, Reference Wedeman2004, Reference Wedeman2012), as evidenced by the high-pressure anti-corruption campaign launched by the Chinese government and Communist Party leaders (Dai, Reference Dai, Rothlin and Haghirian2013; Guo & Li, Reference Guo and Li2015; Sun & Yang, Reference Sun and Yang2016; Wu, Reference Wu2016). The anti-corruption movement has become more and more vigorous in recent years (Han, Reference Han2016).

Early researchers’ work on the cause of corruption focused mainly on macro elements, such as political, ideological, and social factors. Montesquieu (Reference Montesquieu1794) believed that certain regimes were more inclined to be corrupted than the others, particularly authoritarian regimes. Mill's (Reference Mill1966) application of liberal theory considered corruption to be a result of governments’ interference in a free market economy. A more modern macro theory of corruption is modernisation theory, which asserts that a society's corruption level is determined by its level of modernisation (Huntington & Fukuyama, Reference Huntington and Fukuyama1968).

More recently at the individual level, researchers, mainly economists, have focused on officials’ behaviour as one influential factor in corruption. They have defined common corrupt activities as rent-seeking, a behaviour through which the officials use public power to grab benefits, or enterprises bribe officials to win public resources (Buchanan, Tullock, & Tollison, Reference Buchanan, Tullock and Tollison1983). The rent-seeking theory was developed under the framework of the principal-agent model, in which some situations require citizens (the principal) to authorise the power of allocating public resources to an agent, such as a civil servant (Mishra, Reference Mishra2004). The principal-agent relationship may cause asymmetry in information sharing, so the principal is unable to form an exact contract to regulate the agents’ performance due to the lack of relevant information. Thus, when the economic benefit is large and monitoring is limited, the agent may decide to act corruptly, and rent-seeking occurs. Low relative earnings, high unemployment, and advertising will also influence the acceptance of bribes (Goel & Rich, Reference Goel and Rich1989).

However, a simple agency framework is unable to provide a solid and convincing explanation for more complex scenarios (Lambsdorff, Reference Lambsdorff2002a). There is a common issue with interpretations based on economic theories, which all assume that corrupted officials are instrumental and benefit-seeking rent-seekers from the beginning and that corruption can be completed within a short period due to economic incentives and lack of monitoring. However, according to our study of corruption cases in China, these assumptions are not always consistent with actual corruption scenarios. First, for some corrupted officials, the benefits gained from bribery were so small that their value was far less than the risk of being caught. Furthermore, we found in some cases that bribery occurred after an unfair allocation of public resources, to close friends as a favour or from gratitude. Second, not all corrupt officials committed corruption at the beginning of their lieutenancy. Some officials with self-discipline stay away from corruption at first; some even proactively report and unveil the attempted bribes. In a word, political corruption cannot be considered as simply motivated by rent-seeking. Some officials might be enticed or seduced into corruption through an interpersonal process under certain social norms in which psychological factors play a very important role.

Cultural Factors in the Psychology of Corruption

Previous studies of corruption have found many factors associated with the extent of corruption. However, most of these cannot be applied directly to political interventions (Hunt, Reference Hunt2005). During recent years, researchers have begun to show interest in the role of Chinese culture in corruption, especially mianzi (face, 面子) and guanxi (relationships, 关系; Bedford, Reference Bedford2011; Han, Reference Han2016; Schramm & Taube, Reference Schramm and Taube2003; Yu, Reference Yu2008). In Chinese society, the interpersonal relationship can be categorised into two components: expressive components and instrumental components (Hwang, Reference Hwang1987, Reference Hwang2012a). As a result, there are three sorts of interpersonal relationships: the expressive tie (among members of such primary groups as family), the instrumental tie (opposite to the expressive tie, beyond family members in daily transactional life) and the mixed tie, with both elements, where an individual attempts to influence another person by means of renqing (norm of reciprocity) and mianzi (face). Development of the mixed tie goes through three successive stages: initiating, building, and using guanxi. Each stage has different goals, interactive behaviours, and rules of interaction (Chen & Chen, Reference Chen and Chen2004). An individual has to learn moral principles in accordance with the socio-moral order via socialisation to satisfy his/her own desire (Hwang, Reference Hwang2015b). In this case, the petitioner denotes the one who seeks social resources and asks other individuals in their social network for help. Then, the resource allocator will choose an appropriate rule for exchange. The Confucian ethical system of benevolence–righteousness–propriety (ren–yi–li, 仁-义-礼) is used to make this choice according to the Confucian model of mind. The system contains a proper assessment of the intimacy or distance of the relationship (ren), an appropriate rule for the exchange according to the closeness of the relationship (yi) and proper action after evaluating the loss and gain of exchange (li). Different distributive rules for exchange are applicable to different types of relationships (guanxi) during social interactions (Hwang, Reference Hwang2001, Reference Hwang2012b, Reference Hwang2015a). In cases of corruption, if the guanxi between the allocator (the government official) and petitioner (the potential briber) is a mixed tie, the rule of exchange becomes ambiguous and the allocator is likely to be caught in dilemma of renqing: whether the allocator accepts the petitioner's request to unfairly allocate the public resources, or whether the guanxi between the two will be damaged, with the allocator being blamed for breaking the norm of reciprocity (renqing) of Confucian society.

Based on the literature and present situations, we decided to study the process of how good officials become corrupt from the perspective of officials themselves in Chinese culture. Specifically, we aimed to answer this question: How exactly does corruption start between an official and a briber in Chinese cultural context? Many people in Chinese society use mixed ties to place themselves in a more favourable position within other people's network in order to gain access to other people's resources (Hwang, Reference Hwang1987). We can infer that if a would-be petitioner wishes to persuade a stranger (the official) to allocate in their favour, specific means should be designed to involve the potential allocator into the petitioner's own social circle. When the petitioner interacts with the official in the mixed tie, the corruption can happen. Hence, we sought to establish an interactive model of what we called psychological kidnapping to explain this process.

PILOT STUDY

The purpose of the pilot study was to explore corruption behaviours in China and to extract the core psychological characteristics of corrupt officials. The results were to be used as a reference criterion for selecting and analysing materials for the studies to follow, which aimed at exploring the behavioural mechanisms of corruption. This was the most important part of constructing the proposed psychological kidnapping model (Xu, Reference Xu2011).

Method

The researchers in this study read and discussed available corruption cases found in public newspapers and magazines published from 2007 to 2011. The discussion was designed to extract common psychological features of Chinese officials’ corruption.

Results

Through generalising from common characteristics of these corruption cases, we decided to focus on the following characteristics.

The Phenomena of How a Good Official Becomes Corrupt

There are many forms of corruption, and these are also found in the characteristics of corrupt officials. The focus of this study was particularly on officials who were innocent and upright to begin with yet gradually became corrupt. The motivations of corrupt officials appeared twofold: (1) We selected the group of ‘good officials’ instead of ‘rent-seekers’, because rent-seekers aim at seeking benefits and using public power for their own interests, which can be prevented by careful selection, whereas the ‘good-at-beginning’ officials become passively involved in corruption cases due to external influence from relationship with others. The stage of ‘becoming corrupt’ can be prevented by monitoring and supervision, which has important practical implications for policy making. (2) Psychologically, it is useful to study the process of how corruption occurs and develops as it can help identify the features of corruption mechanisms in social interactions.

The Interaction Process in Corruption

Corruption is an interactive behaviour. Most corrupt behaviours require two parties, namely the briber and the bribee (or petitioner and allocator). Deviating from the assumption of isolated individuals socialising to make rational decisions on the basis of self-interest in the West, the norms of reciprocity shaped by the hierarchical relationalism are intense in a Chinese context (Hwang, Reference Hwang1987; Liu, Yeh, Wu, Liu, & Yang, Reference Liu, Yeh, Wu, Liu and Yang2015). Both expressive and instrumental features of the relationship between the two parties change gradually through interactions.

The Conditions for Carrying Out Corruption

The process by which officials become corrupt is gradual. The bribee feels comfortable at the beginning, as with the frog swimming in warm water, unaware of the risk. After receiving many small-value ‘gifts’ from the briber, when being asked to allocate public resources unfairly, the bribee is likely to become aware of the danger. However, by this time, they have already been trapped and have no chance of escaping from a deeply embedded social reciprocal dilemma.

STUDY 1

The purpose of study 1 was to explore and identify the mechanisms and the interactive process by which good officials becoming corrupt.

Method

First, we chose cases from magazines such as Qiu Shi (求实), published by the Communist Party of China's (CPC) school in Jiangxi Province, which studies major issues in contemporary China at both theoretical and practical levels, and from Ji Jian Gong Zuo (纪检工作), published by the CPC Central Committee, which gives a comprehensive summary of the party's disciplinary inspections at the grassroots level. Only those cases that met the three standards established in the pilot study were selected: (1) the cases of a ‘good official becomes corrupt’, (2) the case materials that included the description of the social interaction between the bribed official and the briber, (3) the case materials that included the reasons why corruption happened. A total of 38 cases were selected and analysed.

Second, we categorised and coded the materials based on elements such as the characteristics of the bribers and the bribees respectively (e.g., their attitudes and principles, existing resources, interpersonal relationships and official behaviours), the premises (the cause of corruption, such as guanxi, threat, and so on), the key points (the tipping points throughout the course of the case), and the results of establishing the relationship, including accepting or rejecting the petitioners’ demands in each case. In this process, a descriptive model was established.

Third, based on the model established from the case studies, we formalised an outline and separately interviewed two former officials who were in charge of disciplinary inspections and supervision for the CPC. The purpose of the semistructured interviews was to verify and modify the descriptive model of psychological kidnapping. An analysis was conducted through a three-step coding process. The first step was to obtain meaningful units such as words and sentences from the interviews and define them conceptually. The second step was to group the meaningful units with similar meanings into one category and record the frequency of the units into one large category (Hsieh & Shannon, Reference Hsieh and Shannon2005). The final step was to conclude core categories and move toward a conceptual framework (Drever, Reference Drever1995; Galletta & Cross, Reference Galletta and Cross2013).

Results

The Definition of Psychological Kidnapping

Based on the case studies, discussions, and interviews, we found an interesting phenomenon in bribery cases within the context of Chinese culture, which was defined as psychological kidnapping. Psychological kidnapping is defined as a process in which the kidnapper, in order to attain his/her desired benefits and instrumental goals, develops an affective bond with the kidnapped, who gradually lowers defences and risk perceptions, allowing the kidnapper to use the established relationship to get special considerations and help from the kidnapped. The core of psychological kidnapping is the renqing dilemma (reciprocity).

The Character of Psychological Kidnapping

Relationship change in psychological kidnapping

One of the key elements in a successful kidnapping is the discrepancy in interpretations of the relation between the two people involved in the relationship. In the initial stage of the relationship, the kidnapper has a tendency to use expressive ways of communication that can be rendered as an individual's feelings of affection, warmth, safety, and attachment (Hwang, Reference Hwang1987) without revealing any instrumental intention. In the relationship consolidating stage, the kidnapper aims to gain the trust of the kidnapped by following the rule of expressive interaction. At these two stages, the kidnapped interprets the relationship as an expressive tie. However, in the next stage, when the kidnapper starts to use the relationship (i.e., renqing) for gaining public resources, the instrumental intention is revealed, and the kidnapped official is likely to feel forced to comply. At this point, if the kidnapped official interprets the relationship as a mixed tie, s/he is likely to be caught in a renqing dilemma; if the kidnapped interprets the relation as merely instrumental, s/he can instead formalise a benefit exchange relation with the kidnapper and become a rent-seeker. Then, the kidnapped becomes vulnerable and passive, while the kidnapper becomes mighty and positive. As the former Beijing Haidian District mayor, a corrupted official said: ‘After I had the power, the circle of my friends began to change. Many of my mistakes were caused by the organisation of my friends, they loved me but also hurt me.’

Subjects of psychological kidnapping

The subject positions involved in the psychological kidnapping process are metaphorically the kidnapper and the kidnapped. The kidnapper is the briber (or the petitioner), such as a business person or an interest group. The kidnapped one is the bribee (or the resource allocator), such as an official in public service. The purpose of the kidnapper in establishing a link with the kidnapped is to obtain public resources. They need to establish a secure expressive relationship, because in Chinese social life, social relations spread out gradually, from individual to individual, resulting in an accumulation of personal connections (chaxugeju 差序格局: differential modes of association); morality makes sense only in terms of these personal connections (Fei, Reference Fei1992). Chinese people often do not have a clear distinction between ‘public’ and ‘private’, but only make the judgment in accordance with social distance and closeness of interpersonal relationships (Yang, Reference Yang1995). Therefore, when the relationship between the two turns from strangers to friends, the kidnapped ones usually lower their risk perception and offer help to the petitioners. For example, the former director of Lin Hai Cultural Broadcasting Press and Publication Bureau was very down to earth and hardworking at the beginning of his political life. Because he liked orchids, some people met him in the name of ‘using orchids to make friends’. They continuously gave him precious live orchids as presents, and then became good friends due to the hobby. So, he helped those people who shared ‘friendship guanxi’ with him by using his power in their favour in spite of the law. This shows how he lowered his defences and eventually fell into the quagmire of corruption.

Realisation of psychological kidnapping

The process of being psychologically kidnapped is exactly the same as the ‘boiled frog’ syndrome. If you put a frog into a pan of cold water and turn on the heat, the frog will happily sit there without noticing that the water is getting hot, resulting in death. The kidnapped would feel comfortable at the beginning by enjoying the favour and expressive care offered by the kidnapper without consciousness of the potential danger. For example, the former deputy director of the Chongqing Police Bureau attributed his falling into corruption to ‘falling into the trap of boiled frog, I didn't have any ability to struggle when I finally realised it’. Also, the former communications bureau chief of Wushan County in Chongqing was regretful of making friends with people who had evil intentions, and said: ‘They [the friends] would pull me by a leash once I fell into their trap.’

The most important characteristic of the boiled frog syndrome is the imbalance between risk perception and the cost of rejecting the kidnapper's demands for the kidnapped. Risk perception is lowered by the kidnapper's affectional investment in the relationship and rejection costs, such as the renqing norm, sense of indebtedness, payback cost, and risk of whistle-blowing, which keep increasing as long as the kidnapped continues to accept affectional seduction from the kidnapper. Then the official falls into a coerced situation without even being aware of the danger.

The Interaction Process Model of Psychological Kidnapping

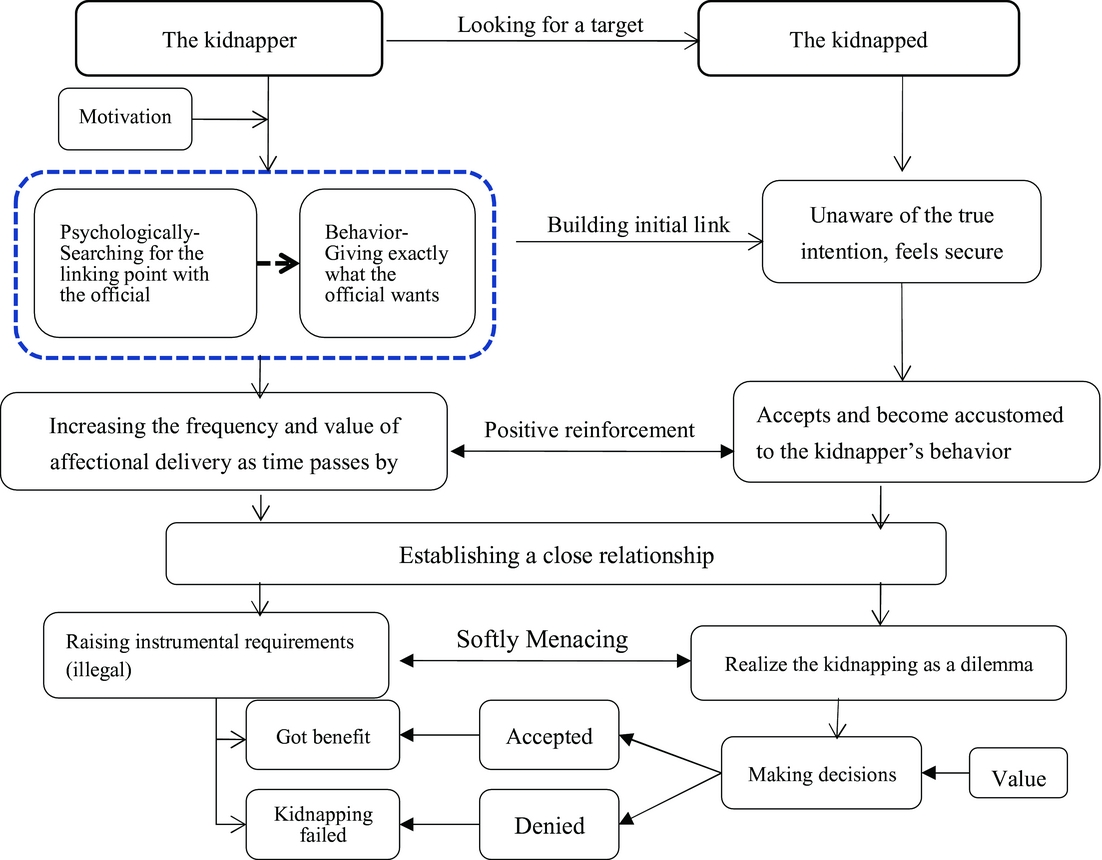

The psychological kidnapping process is a series of interactions between the kidnapper and the kidnapped. We built the descriptive model through analysing the key elements and junctures of the kidnapping process, such as the transformation point, psychological strategies, and risk perception (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Model of psychological kidnapping.

In the process of psychological kidnapping, the kidnapper actively seeks to build a relationship with those who have the authority to allocate resources. At an early stage, the kidnapper uses a series of psychological strategies to establish a close relationship with the kidnapped. The kidnapped accepts and gradually becomes accustomed to the behaviour of the kidnapper, without being conscious of the true instrumental intentions of the kidnapper. The guanxi will change from strangers to close ‘friends’. Later, the kidnapper will use affectional blackmail, such as ‘we are friends and you should help your friends’ to softly menace the kidnapped to corruption. When the kidnapped realises the true intentions of the kidnapper, the guanxi has been already established and the kidnapped is trapped in a renqing dilemma. If the kidnapped treats civic rights as personal, s/he would accept the demands from a ‘friend’ and become involved in corruption. However, if the kidnapped does not want to violate the principle of law and denies the demands from a friend (as a social network is a framework for evaluating the behaviour of people in appropriate situations; Barnes, Boissevain, & Mitchell, Reference Barnes, Boissevain and Mitchell1975), s/he may face the risk of being condemned or rejected, because when interacting with other people, one should start with an assessment of the relationship between oneself and others along two cognitive dimensions: intimacy/distance and superiority/inferiority. Instead of treating everyone with equal affection, according to the Confucian idea of benevolence, one should consider the principle of favouring the intimate (Hwang, Reference Hwang2001). The decision would depend on the judgment of risk and benefits.

STUDY 2

The purpose of study 2 was to sum up the characteristics and process of ‘good officials becoming corrupted’ and to confirm the psychological kidnapping model.

Method

Sample

A theoretical sampling method was used, which meant choosing the group and materials that could answer the most important questions of timing, scene, and participants for the issues of concern (Weiss, Reference Weiss1995). With psychological kidnapping, the concern is why good officials ‘fall into’ corruption. Therefore, the sampling process was conducted through openly published interviews of corrupt officials who were convicted within the nearest decades under the sampling frame of (1) non-rent-seeking officials, (2) the materials should depict the changing process of the official from incorruptible to corrupted, and (3) focusing on the role of renqing during the interaction between the official and the kidnapper. Under this framework, 19 cases were found suitable for the research purpose. The characteristics of these cases included: (1) the sources — the cases were from both government websites such as Xinhua Web, and non-government websites such as Phoenix Net or Tencent NetFootnote 1 ; (2) the region — the officials in these cases were from 12 provinces; (3) the positions — the officials worked in party and government offices, public institutions, or state-owned enterprises; (4) the rankings — the officials were from bureau to departmental level, mainly departmental or deputy departmental level.

Coding

Grounded theory was used in the coding, which is a widely used qualitative research technique (Hsieh & Shannon, Reference Hsieh and Shannon2005; Stemler, Reference Stemler2001) aimed at developing theories inductively from data, rather than testing existing theories or generating only themes (Service, Reference Service2009; Strauss, Reference Strauss1987). Three analysing perspectives were established according to the phenomenal model of psychological kidnapping: identity analysis, process analysis, and characteristic analysis. See Table 1.

Table 1 Text Analysis of Coding

There were three steps in the coding: open coding, axial coding, and selective coding. In open coding, data is read word by word to derive codes (Huberman & Miles, Reference Huberman and Miles1994) and capture key thoughts or concepts. We decomposed the text of the interviews into separate sentences, phrases or words, maintaining the units relevant to the question or phenomenon we were interested in. Then we grouped units with the same connotations, forming and naming new units (a1, a2, a3 . . .). To avoid the subjective bias of the coders, the coding of step 1 was done separately by four coders. Open coding extracted 148 units.

In axial coding, codes were sorted into categories based on how different codes were related and linked (Coffey & Atkinson, Reference Coffey and Atkinson1996). Researchers integrated the units identified in step 1, then organised and grouped them into meaningful units. Through this process, the scattered words or phrases could be collected and linked to each other, laying a foundation for the next coding step. The categorical units formed in this step were named by the capital letter ‘A’, as A1, A2, and so on; 21 categorical units were selected from this stage.

In selective coding, core units were chosen from 21 categorical units from the axial coding stage, named as B1, B2, and so on. The other units were gradually gathered around the core units (see Table 2). There were 11 second level categorical units that emerged through comparison and combination (B), which were divided into four groups: the official's character (B1-3), the official's psychological process (B4-5), the resource's character and delivery (B6-10), and the resources output process ending (B11). These secondary categories could be analysed from three possible perspectives: identity analysis, process analysis, and characteristic analysis.

Table 2 Coding, Categorical and Core Units in all 19 cases

Analysis

Identity Analysis

The results of data analysis showed that throughout the course of interactions between the briber and the official, the official's identity was consistent with that of a kidnapped individual, as the risk alert level decreased and the sense of menace appeared; while the briber's identity was consistent with that of a kidnapper, featuring resource delivery in the form of returned favours for instrumental purposes.

The kidnapper and the kidnapped have different characteristics in the kidnapping relationship. As the psychological kidnapping model shows, the kidnapped is honest, innocent and competent (B1) with no intention of rent-seeking at first (A1/2/3). Many people are attracted by the power of allocating public resources (B2) to build relationships with him/her (A11). At the same time, the official is in need of some personal resources that cannot be obtained by himself/herself (B3). Once the official accepts the personal resources delivered by the kidnapper, the perception of risk may decrease (B4) and the resources would be interpreted as renqing or favour instead of briberies (B6). However, when the ‘friend’ begins to ask for payback by requesting an unfair allocation of public resources, the official would feel a sense of being compelled (B5) and be trapped in dilemmas that place him/her in difficult moral predicaments, requiring him/her to weigh whether the moral end (helping friends) can justify the immoral means (corruption). Chinese people tend to rely on relationship orientation when they encounter moral judgments (Wei & Hwang, Reference Wei and Hwang1998). The renqing rule emphasises that once an individual receives a favour from others, s/he is obligated to reciprocate in the future. Refusing the kidnapper's request will result in a breakdown of mutual affection (ganqing polie, 感情破裂) and the kidnapped will be despised by other guanxi members as dishonest or lacking human feelings (Wang, Reference Wang2016). Therefore, the cost of saying ‘no’ to those who share strong ties is high.

On the other hand, the briber (kidnapper) depicts a self-image of being honest, considerate, and reliable at the beginning. During the relationship establishing process, s/he shows affection on the surface but has a hidden instrumental purpose (B8). Most of the gifts (including the emotional support) are delivered uninterruptedly from the kidnapper with high frequency, satisfying the need of the kidnapped with high personalisation, but nothing is asked for in return (B7). After gradual material delivery and emotional expression (B10), the guanxi bondage is formed. See Table 3.

Table 3 The Kidnapper and The Kidnapped's Characteristics

Process Analysis

The process of psychological kidnapping can be divided into three stages. See Table 4.

Table 4 Characteristics of Psychological Kidnapping in Different Stages

Stage 1: Attraction and acceptance

At this stage, the kidnapper's main goal is to establish a relationship. The official who has the power of allocating public resources (B2) is competent and a non-rent-seeker. The kidnapper delivers both material resources (personalised gifts) and emotional support to establish a relationship with the official (B7/9/10). As the former director of Wu Shan Transportation Bureau said: “We [with the kidnapper] just talked about our families that day. We found that we shared some common interests and we both were very pleased. I thought Zhou could be a great friend. And Zhou never mentioned the topic of contracting the project, which made me more determined about my own ideas.”

Stage 2: Trust and integration

At this stage, the relationship is strengthened continually. The official starts to accept the resources delivered by the kidnapper without noticing the true purpose of the kidnapper. The official is likely to evaluate the relationship as expressive ties (B6) based on the kidnapper's delivery style, such as high frequency and affectional influence, without asking any payback (B7/B9/B10); the perceptions of risk may decrease (B4).

Stage 3: Collusion or fracture

After a while, when the kidnapper feels that the relationship has been consolidated, s/he may make a request to use the official's power for allocating public resources as a favour (B8). At this time, the official cannot resist the request because of the favours (renqing) s/he owes to the kidnapper. Thus, the corruption begins (B5). The relationship will terminate if the official has retired or been investigated. The kidnapper would then stop delivering resources as soon as the official lost his/her power (B11).

Characteristics Analysis

The characteristics of psychological kidnapping can be summed up in terms of eight components: precondition, means, kidnapping point, psychological process, results, types, functions, and forms.

Precondition

First, the kidnapper uses affectional investments to establish a safe and reliable interpersonal relationship. The kidnapper delivers resources to the official from the beginning without asking for anything in return, which is strongly asymmetric regarding the reciprocal expectations. Second, the official is passive (A9). The official may feel a sense of ‘being led by the friends’ (B5), which means s/he has to obey her/his friends’ requirements, with a lower sense of authority and control, and more stress. It is a mutual selection process, with the kidnappers searching for officials who are easily enmeshed and the officials searching for people who can be true friends.

Means

From the start, the kidnapper aims to provide what the official likes or needs, be it hobbies, inexpensive collections, or assistance for family members. Affective interactions will increase the dependence of the kidnapped on the kidnapper.

The kidnapping point

The relationship between the kidnapper and kidnapped transforms from defensive (A8) to hard-to-refuse (A9). The early investment turns into benefits and who has the initiative changes. The kidnapper seeks a greater influence over the kidnapped to obtain the power controlled by the kidnapped. The turning point is when the kidnapped official feels safe about the relationship and the kidnapper feels that it is an appropriate time to make a request.

Psychological process

As mentioned in the identity analysis, the kidnapped official's risk perception declines step by step and the cost of rejecting the kidnapper's demand increases.

Results

There are two possible results of psychological kidnapping. First, the kidnapping is successful. Under this situation, the kidnapped accepts the requirements, so the kidnapper gains the benefits and rewards s/he has wanted, such as getting investment illegally or a job through the official's power, in order to take a shortcut. Second, the kidnapped refuses the requirements, so the relationship may be damaged. Under this situation, ‘revenge’ (i.e., whistle-blowing) may occur.

Types, functions, and forms

The types of psychological kidnapping are various, including political, economic, and affectional (family, marriage). The functions of psychological kidnapping are to protect oneself, gain resources and take advantage of others’ influence. There are two forms: (1) Direct kidnapping, which happens only between the kidnapper and the official who is kidnapped. In other words, the petitioner only ‘makes friends’ with an allocator to establish the expressive tie. (2) Indirect kidnapping, when the kidnapping happens among the kidnapper and the people around the official who is kidnapped, such as when the petitioner ingratiates him/herself with the allocator's spouse, children, other family members, and staff.

Outcomes

Process of Psychological Kidnapping

The psychological kidnapping process contains three main stages. In the first stage, the kidnapper initiates the relationship with the official by searching for a common link and starts to deliver resources to the official. In the second stage, as the relationship develops, the trust between the two parties is formed and a close tie is established. At this point, the kidnapper asks for almost nothing in return but continues to deliver resources to the official in order to strengthen the relationship. In the third stage, the kidnapper attempts to gain benefits by accessing the official's political power, perhaps through soft menace. At this point, the official has been subtly coerced to seize public resources on behalf of the kidnapper. It also includes the end stage, where the official loses power and the kidnapper stops delivering resources.

Characteristics of Psychological Kidnapping

There are three main characteristics of psychological kidnapping: (1) Concealed delivery, which is when the kidnapper hides his/her true purpose at the beginning by being nice to the official and delivering resources as affectional investments and which may give the official a sense of security. (2) Risk and cost imbalance, when the official's perception of risk is reduced by the affectional tie established through expressive resource deliveries by the kidnapper. However, the cost to resist the kidnapper's request keeps increasing, creating a cognitive dissonance, sense of indebtedness, possible damage to the social network, or the possibility of whistle-blowing, and thus the risk and cost become imbalanced. (3) Soft menace, which means that the kidnapper may use soft factors such as relationship, favour or stress to force the official to accept the request instead of overt violent menace. For example, an official said: ‘Whatever difficulties I encounter in my family, they [the friends] are always eager to help me. And when it comes to working together with them to make money, I cannot say no to them.’

Essence of Psychological Kidnapping

As a special tie, the mixed tie between the kidnapper and the kidnapped contains both an expressive component and an instrumental component. There is no obvious boundary between the components in Chinese culture. In an attempt to reach his instrumental goal, an individual sometimes establishes expressive ties with powerful others. However, it takes time for such a tie to form; therefore, it is necessary to hide the instrumental purpose before the relationship has been established, so the kidnapped is unaware of the truth and the danger. The kidnapper uses the expressive tie as an instrument to procure the desired material resources. As an official recalled: ‘Mr Zhou never mentioned contracting the project, which helped deepen our friendship. One day in 2003, when my daughter was about to start her university in another city, Zhou told me that he rented an apartment for my daughter right next to her school so that she could live nearby. I was so moved by his consideration and accepted this gift. . . . In early 2006, many roads in Wushan needed reconstruction. Zhou, who never asked any favour from me before, suddenly visited me, proposing to contract the project.’ During this process, their relationship changed from an expressive tie to an instrumental tie for the official who was kidnapped.

General Discussion

The current research used qualitative analyses method to study corruption cases and interviews with the authorities in question, to answer the question of how good officials become corrupt in a Chinese cultural context. By analysing the sequence and key points of the psychological kidnapping process, the researchers summarised the characteristics of the corrupt officials involved and the interpretation of their relationship. The concept and model of psychological kidnapping were raised as a result, which may provide a foundation for future studies on corruption psychology in Chinese culture.

There are some conditions for successful psychological kidnapping. The first and foremost is the dominance of the renqing principle. In Chinese culture, the rule of renqing is a derivative of the norm of reciprocity, which guides the social exchange of resources in the mixed tie (Buckley, Clegg, & Tan, Reference Buckley, Clegg and Tan2006; Lu, Reference Lu2012; Yang & Wang, Reference Yang and Wang2011). To ordinary people, Chinese ethics have a practice of such maxims as ‘do not forget what other people have done for you (知恩图报)’. After helping the official, the kidnapper can rightly look forward to a return, because a reciprocal action cannot be neglected by the official when the kidnapper is in ‘need’ (Hwang, Reference Hwang1987). In other words, a public official may receive certain types of favours from others in a guanxi network, such as getting assistance when encountering a difficulty. These favours thus cultivate a sense of obligation on the part of the kidnapped, who is willing to find ways to pay back the favour by using her/his resource allocation power. The reciprocity is so important that it helps to maintain the balance of the relationship, otherwise it may bring disgrace to the official's close associates.

Another condition is the guanxi orientation (or relationalism). In China, guanxi prescribes different sets of rules for identifying and dealing with in-groups and out-groups (Chib, Phuong, Si, & Hway, Reference Chib, Phuong, Si and Hway2013). According to the renqing rule, people should maintain a good guanxi, which is a complex construct of interpersonal interactions (Bell, Reference Bell2000; Chen & Chen, Reference Chen and Chen2004; Chou, Cheng, Huang, & Cheng, Reference Chou, Cheng, Huang and Cheng2006; Kriz, Gummesson, & Quazi, Reference Kriz, Gummesson and Quazi2013), with others in the ties mix. The normative function of a guanxi network is to enhance the opportunities, means, and incentives for public officials to engage in corruption (Zhan, Reference Zhan2012), which means that the principle of reciprocity (bao, 报) and the norm of gift-giving (songli, 送礼) could encourage government officials to meet the demand from guanxi networks, regardless of the legal norms designed by the state authority. When an individual's interpersonal behaviour is in violation of the renqing rule, his/her feelings of guilt may be initiated (Feng, Xu, Long, & Zhang, Reference Feng, Xu, Long and Zhang2015). Taking the norm of gift giving into account, the official who is kidnapped will feel shame and guilt if s/he refuses the petitioner's requests (Hwang, Reference Hwang1987). The norm of gift giving in a guanxi network helps bring down a major barrier to relationship establishment in corrupt cases (Li, Reference Li2011). Guanxi networks normalise corrupt transactions through the neutralisation process (Wang, Reference Wang2016), where the bribees use it to justify their behaviours and lessen their responsibilities.

Third, it is crucial for Chinese people to manage his/her self-image and maintain mianzi in front of others (Hu, Reference Hu1944; Hwang, Reference Hwang1987; Servaes, Reference Servaes2016), or what is called ‘face work’. The kidnapped should ‘give mianzi (给面子)’ to the kidnapper in order to exchange renqing (Zhai, Reference Zhai2005). Face is lost when the individual fails to meet essential reciprocal requirements (Ho, Reference Ho1976). If the official helps the kidnapper, they will both feel enhanced in social status and high self-esteem (you mianzi, 有面子). However, if the official refuses to help, he/she will make the kidnapper ‘lose mianzi (丢面子)’, which may cause him/her suffering uneasiness in the long run. As an official recalled:

I embarked on the road to crime in 2002. One afternoon, a Ji'nan economic and trade company staff Mr Chen asked me to help him by signing an import car quota. I did not agree at the beginning, because I was not in charge of the work. . . . But I had a good impression of his classmate Mr Wang, so Chen let Wang come to me again and again to ask for the favour. . . . Later, to give Wang a mianzi, I signed my name on the report by the company to the provincial Economic and Trade Commission Office.

Last, but not least, as an old proverb goes, ‘The barefoot is not afraid of that in shoes’, so the kidnapped officials are worried about their own benefits. They want to keep their honour and high status as a government employer, while the kidnappers have barely anything to lose. Moreover, in some cases of psychological kidnapping (such as political cases), refusing the requirements means fighting against a stronger invisible power which may lead to self-destruction.

The research about psychological kidnapping phenomena will have some practical value in constructing an ‘unwilling-to corrupt’ society. In the practice of reducing corruption in China, President Xi Jinping proposed to focus on creating a political atmosphere of ‘dare-not-to (不敢腐), unable-to (不能腐) and unwilling-to corrupt (不想腐)’ in the Fifth Plenary Session of the 18th CPC Central Committee, which has pointed out the direction for the current anti-corruption campaign (Liao, Reference Liao2009). The major threat of corrupt transactions is the risk of punishment (Lambsdorff, Reference Lambsdorff2002b). At the dare-not-to stage, a harsh punishment should be imposed on corruption to enhance the risk perception of officials. Because guanxi can facilitate corrupt transactions (Bian, Reference Bian1997; Wang, Reference Wang2014, Reference Wang2016) at the unable-to stage, setting up clear rules of social interaction is one way to evade the trouble of renqing as a pathway to corruption. Institutions should perfect and reinforce monitoring, such as being transparent. At the unwilling-to stage, the government should foster officials’ factual beliefs about the inherent immorality of corruption (e.g., the autonomous immoral disposition of corrupt officials) and justice analysis of cost-benefits between renqing and the law. Even reading essays about the morality of an action can change readers’ beliefs about its costs and benefits (Liu & Ditto, Reference Liu and Ditto2013). In addition, civil servants’ awareness of separating instrumental goals from expressive ties should be raised and strengthened by the government.

This study also had a few limitations. First, cases were all gathered from openly published interviews from magazines and newspapers, which might be influenced by political factors. Second, just as with other social characters, the officials were likely to shirk their responsibility in corruption by blaming circumstances or other persons for bad outcomes (Sedikides, Campbell, Reeder, & Elliot, Reference Sedikides, Campbell, Reeder and Elliot1998). People tend to restructure their actions to appear less harmful and minimise their role in the outcomes of their actions, or attenuate the distress that they cause to others in moral disengagement (Bandura, Reference Bandura1999; Bandura, Barbaranelli, Caprara, & Pastorelli, Reference Bandura, Barbaranelli, Caprara and Pastorelli2002). By blaming the kidnappers, the officials could retain some shred of morality for themselves and offer kidnapping as an excuse for corruption. Third, besides renqing, there may also be other social relationship concepts such as favour and face involved in the corruption interactions in Chinese culture society (Hwang, Reference Hwang1978). Therefore, other explanations need to be explored in the future.

Conclusion

A concept and model of psychological kidnapping was developed to answer the question of how good officials become corrupt. The process of psychological kidnapping includes three stages: attraction and acceptance, trust and integration, and collusion or fracture. The concealed delivery of resources, the imbalance of the official's risk and cost perceptions, and soft menace from the kidnapper are three important characters defining psychological kidnapping. Renqing plays an essential role in the process of psychological kidnapping.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the editor and two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments, and to the researchers who participated in the coding process.