Introduction

On Monday last the members of the Orange societies of this town this year resolved to commemorate the exploits of the Prince of Orange by a public procession, before dining at their various club-houses. London-road, near the monument, was the place appointed for the formation of the procession, and thither the members of the various lodges proceeded at an early hour. A little before ten o’clock a large body of men was seen advancing up London-Road. They wore overall smocks, and had the appearance of navigators or men employed at the dock works. Some of the men were armed with large stones, which they had brought from a distance, whilst others bore sticks or staves in their hands. No sooner had the body of men arrived near the monument than they discharged a volley of stones at the Orangemen. The Orangemen, of course, resolved upon repelling their aggressors, and a regular melee then took place; stones flew about almost as thick as hail, and the Orangemen fought with their hands, sticks, or whatever instruments they could bring into requisition. (Gore’s Liverpool General Advertiser 17/07/1851)Footnote 1

The riots in Liverpool in July 1851 reveal two significant connections with time. The first, and most obvious, is the place of the July Twelfth celebrations in Liverpool’s social and cultural scene. This annual celebration has a convoluted history. The date commemorates the victory of Irish Protestant forces over supporters of the deposed Catholic king, James II, at the Battle of Aughrim in 1691. However, after the foundation of the Orange Order in 1795, the celebration also came to be associated with Prince William of Orange’s original victory over King James II, at the Battle of Boyne a year earlier (Leniham Reference Lenihan2003). From Ireland, this tradition was brought over to Liverpool in the early nineteenth century, becoming a focal point for sectarianism for more than a century (Roberts Reference Roberts2015: 142; see also Neal Reference Neal1988; Waller Reference Waller1981). The riots of 1851 resulted in nearly 100 arrests, and the role of these annual celebrations in fomenting violence was not lost on local commentators. Gore’s Liverpool General Advertiser (17/07/1851) declared,

We hope this will be the last party procession in Liverpool, and that the magistrates will strenuously prohibit them in future. The Orangemen held themselves justified in walking this time, if one folly can justify another, by the procession which the Hibernian societies held on St Patrick’s day. But this fruitful source of disturbance must for ever be suppressed.

However, these events reveal another, equally important, connection with time. Political gatherings, especially those on this scale, are constrained and structured by the everyday schedules of their participants. In this case, those involved in the July Twelfth celebration were clearly absent from work on that particular Monday, and so too were the crowds of people who opposed them. The fact that the “large body of men” who originally attacked the Orangemen are described as wearing “overall smocks” and having “the appearance of navigators or men employed at the dock works,” suggests that they may have come from work. But, if so, they don’t seem to have been constrained to stay there by their employers. This deep connection between protests and people’s ordinary daily, weekly, and annual calendars opens up two parallel strands of research. The first is to explain the temporal patterns of political protest (McAdam and Sewell Reference McAdam, Sewell, Goldstone, Doug, Perry, Sewell, Sidney and Charles2001). The other is to use records of political events to uncover historical patterns of time use (Harrison Reference Harrison1986). This essay is primarily concerned with the latter, using three catalogs of political events to try to answer several questions about time use in Britain over the long nineteenth century.Footnote 2

The historiography in this area is still heavily indebted to the work of E. P. Thompson. In his classic portrait, preindustrial England was characterized by irregular rhythms of work: in place of orderly “clock time,” people’s lives were oriented around discrete tasks and the natural cycles of the sun, the moon, and the seasons, while bouts of idleness followed stretches of extremely intense working. All this changed with the Industrial Revolution, when the discipline of relentless steam power and factory labor triggered a painful transformation in the way time was understood and in people’s patterns of work and play (Thompson Reference Thompson1967). Although Thompson’s account remains enormously influential, there have been numerous challenges to it, with some questioning how irregular the preindustrial world really was, and others arguing that those older cultures of work persisted far into the industrial era.

In a period for which systematic time-use survey data is unavailable, it has been extremely difficult to test Thompson’s hypotheses systematically. In fact, the extensive literatures that have developed examining the tradition of Saint Monday, the “industrious revolution,” and people’s changing perceptions of time rely on a fairly narrow evidential base. Therefore, despite the ingenuity of several generations of historians, there is much that we don’t know and several points of disagreement.

This essay makes a modest contribution to that evidential base by using political events as a proxy for time use. I draw on three event catalogs: one covering political meetings in northern England between 1790 and 1848 (Navickas Reference Navickas2020); one covering riots in Manchester, Liverpool, and Glasgow between 1800 and 1939 (Tiratelli Reference Tiratelli2019); and one covering contentious gatherings in Britain from 1758 to 1834 (Tilly and Horn Reference Tilly and Horn1988). These catalogs provide new evidence for several debates in nineteenth-century social history. First, they suggest that Monday was a popular day of holiday across Britain in the early nineteenth century, before declining slowly in the mid-1800s. It therefore supports what I will call the “orthodox narrative” about the tradition of Saint Monday against its recent challengers. Second, these sources provide evidence that political organizers in the early nineteenth century generally respected the Christian reluctance to “profane” the Sabbath with worldly affairs. Third, these catalogs also provide some speculative evidence that time became more ordered and structured as the nineteenth century wore on. Further research and alternative sources will be needed to validate these three arguments. But I hope that they can contribute to a growing body of evidence about time use in the nineteenth century.

Labor, Time Discipline, and Industriousness

The research program that most directly followed Thompson’s interest in the relationship between patterns of work and industrialization has emerged around Jan de Vries’s account of the “industrious revolution”: a dramatic transformation of work and consumption in Britain, which de Vries locates in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries (de Vries Reference Vries1994, Reference Vries2008). De Vries’s work was originally motivated by an empirical puzzle: although the real value of wages seems to have been stagnant for most of this period, “probate inventory studies and direct consumption measurements … [reveal] an ever-multiplying world of goods, a richly varied and expanding material culture, with origins going back to the seventeenth century and exhibiting a social range extending far down the social hierarchy” (de Vries Reference Vries1994: 254–55). To reconcile these seemingly opposed trends, de Vries argues that increased demand for market-supplied goods, alongside changes in relative prices, led households to reallocate time away from leisure activities and production for direction consumption, toward wage labor (de Vries Reference Vries1994: 257; see also Koyama Reference Koyama2012). This transformation in British attitudes to work, play, and desire constituted a consumer revolution (c.f. Litvine Reference Litvine2014) and laid the foundations for the later period of industrialization.

This argument has a prestigious sociological inheritance, echoing Marx’s work on the generalization of wage labor and Weber’s interest in the cultural roots of capitalism. But, as an empirical proposition, it has prompted skepticism in some quarters. In principle, increased working could mean three things: working more intensely, working longer hours per day, and/or working more days per year. Measuring any of these three elements accurately for the early modern period is fraught with difficulties, and different sources and methodological approaches have produced conflicting findings. On the skeptical side, Gregory Clark has questioned whether agricultural workers really could have increased their labor by the proportions that de Vries suggests (Clark Reference Clark2001; Clark and van der Werf Reference Clark and Van Der Werf1998). He cites records from estates in Bedfordshire, Cambridgeshire, Northamptonshire, and Derbyshire, which show that agricultural laborers already worked nearly 300 days a year in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries (that is hard manual labor, six days a week, all year round, with only a few scattered holidays over Christmas, Easter, and Whitsun). In a more systematic comparison of annual salaries with daily wages, and daily wages with piece rates, Clark also argues that the intensity of work was high and stable across the early modern period. This chimes with recent evidence from court depositions in the rural southwest of England, which suggests that, between 1500 and 1700, “the demands of rural life in a complex, commercialized economy, in a society obsessed with order and with a well-developed disciplinary infrastructure, meant that long hours of regular, clock-orientated, often closely policed work, were a fact of life” (Hailwood Reference Hailwood2020: 121).

However, other scholars have argued that the early modern working year was much shorter than is conventionally assumed. Judy Stephenson (Reference Stephenson2020), for example, used records from a masonry firm working on the construction of Saint Paul’s Cathedral in the early eighteenth century to argue that workers faced a highly irregular working year, with demand for labor operating as the key constraint.Footnote 3 While this suggests that there was the potential for increased working, other historians have argued the case more directly. Robert Allen and Jacob Weisdorf (Reference Allen and Weisdorf2011) use wage and price series to calculate the number of days that rural and urban laborers would need to work to buy a fixed basket of goods. On this basis, they argue that agricultural workers saw two industrious revolutions between 1525 and 1830, both driven by hardship and high prices.Footnote 4 But for urban workers, they argue that the “growing gap between their actual working year and the work required to buy the basket provides great scope for a consumer revolution” (Allen and Weisdorf Reference Allen and Weisdorf2011: 715). Jane Humphries and Weisdorf (Reference Humphries and Weisdorf2019) come to a similar conclusion through a different method. Borrowing Clark’s logic, they assume perfect arbitrage between daily wages and annual salaries, reasoning that, if one was higher than the other, then workers would swap between the two. Using a wide sample of annual and daily contracts, they then calculate how many days you would need to work at a day rate to earn the equivalent of an annual salary, and so argue that labor input increased steadily between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Further supporting evidence (albeit from a later period) comes from Hans-Joachim Voth’s pioneering use of court witness statements to track who was doing what when (Voth Reference Voth1998, Reference Voth2000, Reference Voth2001). Looking at depositions from the Old Bailey in London and the Northern Assize circuit, Voth argues that there was a significant increase in labor input between 1760 and 1800, followed by a plateau through to the 1830s. Interestingly, Voth also argues that the working day was fairly constant throughout this period (7 am–7 pm), but that the number of days worked increased to more than 330 days a year. Those extra days came from two sources. The first was a decline in the number of religious and political holidays; a claim supported by literary sources (Freudenberger and Cummins Reference Freudenberger and Cummins1976) and by the scarcity of holidays observed in factory records from the late eighteenth century (e.g., Peers Reference Peers2009: 51–57), but contradicted by evidence from construction workers (Stephenson Reference Stephenson2020: 413) and agricultural laborers (Clark and van der Werf Reference Clark and Van Der Werf1998: 836–37) in the early 1700s. Voth’s second source of increased working days, and the one that I will focus on in this essay, was the disappearance of Saint Monday.

Saint Monday, the Sabbath, and the Ordering of the Working Week

The tradition of Saint Monday has an important place in Thompson’s depiction of preindustrial work patterns. He describes the normal working week as characterized by “alternate bouts of intense labour and of idleness,” with Monday as “Sundayes brother” and work slowly picking up in the latter half of the week (Thompson Reference Thompson1967: 72–23). This tradition of taking an impromptu holiday on Monday was in part associated with licentiousness and heavy drinking, but more material concerns also appear in Thompson’s account: he cites a report to the US Consul in 1875 that claimed that “Monday idleness is, in some cases, enforced by the fact that Monday is the day that is taken for repairs to the machinery of the great steelworks” (Young Reference Young1875: 408–9: cited in Thompson Reference Thompson1967: 74). In this portrait, Saint Monday was closely associated with an irregular pattern of work. It was not an officially ordained holiday, but rather characterized a working week that was highly variable, task-oriented, and, at times, haphazard. Most importantly, it represented the autonomy of individual artisans over the labor process and over their own time. For Thompson, the erosion of this tradition in the face of industrial capitalism was therefore an attack on the independence and agency of the British working class.

Voth broadly agrees with Thompson that the erosion of Saint Monday was bound up with the development of industrial capitalism. And he is similarly pessimistic in his evaluation of that change: more work and less leisure put real pressure on the living standards of the British working class, despite the huge growth in national wealth triggered by industrialization (Voth Reference Voth2001: 1080; see also Allen Reference Allen2009). But the details of Voth’s history of Saint Monday represents a substantial attack on the orthodox account of its rise and fall. Saint Monday is generally assumed to have emerged in the mid- to late 1700s, rather than finding its roots in the distant past (Hailwood Reference Hailwood2020: 105–7; Rybczynski Reference Rybczynski1991). It is also normally believed to have endured into the mid-nineteenth century, even surviving into the 1920s and 1930s in some places (Walton Reference Walton2014: 206–7). Voth, in contrast, argues that Saint Monday was widespread in London in the 1760s but had largely disappeared by 1800, and that there is little evidence to support its existence at all in northern England (Voth Reference Voth2000, Reference Voth2001).

Voth’s intervention in fact continued a debate that had been raging since the 1970s. Early attempts by social historians to test Thompson’s thesis initially relied on literary sources, which abound with references to Saint Monday all the way through the nineteenth century (see Hopkins Reference Hopkins1982). According to Douglas Reid’s (Reference Reid1976) influential account, Saint Monday remained common until the mid-1800s, when it was gradually eroded by the Saturday half-day movement, which united employers concerned with enforcing labor-discipline with moral campaigners concerned to promote temperance and respectability amongst urban workers. Therefore, while agreeing with Thompson about the nature of Saint Monday, these authors suggested that it lasted far beyond the birth of industrial capitalism.

However, these accounts have been criticized for their reliance on the complaints of employers, rather than direct measurement of working time. In particular, the various reports of Parliament’s Children’s Employment Commission feature heavily, and the overwhelming majority of their witnesses were employers, who may well have been predisposed to complain about ill-discipline and unruly workers. One response to this methodological challenge has been to turn to microhistory. Peter Kirby (Reference Kirby2012) examined work records from Wylam Colliery, Northumberland, between 1775 and 1864 to track changing patterns of work in the coal field. His central finding is that, while there were no full shutdowns of the colliery on Mondays, short working was extremely common, and that this tradition only disappeared with the emergence of half-day Saturdays in the 1850s. Kirby also argues that the tradition of Saint Monday probably reflected the physical exhaustion of workers, rather than drinking and revelry. Sarah Peers’s (Reference Peers2009) analysis of work records from Quarry Bank Mill, Cheshire, in 1790 also shows that Monday absenteeism was common for male and female workers of all grades. However, by framing her findings in the language of “resistance,” she returns to a quasi-Thompsonian perspective, seeing absenteeism as evidence of working-class agency in the face of industrial capitalism. Interestingly, two recent studies from eighteenth-century London—one of masons working on the construction of Saint Paul’s Cathedral from 1700 to 1709 (Stephenson Reference Stephenson2020), and another of clerks at the Bank of England in 1783 (Murphy Reference Murphy2017)—found no evidence of Saint Monday at all in those particular (and somewhat unusual) workplaces.

Given the obvious limitations of using sources from a single location, other quantitative studies have instead relied on indirect measures of time use. Jeremy Boulton (Reference Boulton1989) used data on the timings of weddings from across England as a proxy, finding that the early modern period had a highly irregular working week, which gradually came to be structured around a Sunday–Monday weekend in the early nineteenth century. This pattern is particularly noticeable in the big cities of Birmingham, Manchester, and London, with far less evidence of Saint Monday in rural areas. Reid (Reference Reid1996) took a similar approach, arguing that the timing of marriages in Birmingham, Bristol, Blackburn, and Manchester show that Saint Monday was widely observed across England in the early nineteenth century; but it then slowly declined, first in the factory towns, and then more generally by the end of the century.

Mark Harrison took a similar approach but used the broader category of “mass phenomena” (public meetings, parades, demonstrations, etc.) as a proxy for time use, constructing a catalog of 245 crowd events in Bristol between 1790 and 1835 (Harrison Reference Harrison1986; for commentary see Landes Reference Landes1987 and Harrison Reference Harrison1987). Harrison’s central claim is that the working week in the early nineteenth century was “ordered, predictable and long,” revolving around a “working Saturday, domestic Sunday and outdoor Monday” (Harrison Reference Harrison1986: 136, 157). Harrison is explicit in his belief that Saint Monday was a quasiofficial holiday, rather than a side effect of heavy drinking and disorderly behavior. This contradicts Thompson’s focus on irregularity and is needed to sustain Harrison’s general argument that time in the early nineteenth century was “structured, respected and constraining” (ibid.: 166). However, this claim is difficult to assess because, as I will go on to argue, he provides no points of comparison. We therefore cannot say whether the working week in early-nineteenth-century Bristol was any more or less ordered than at any other point in history.

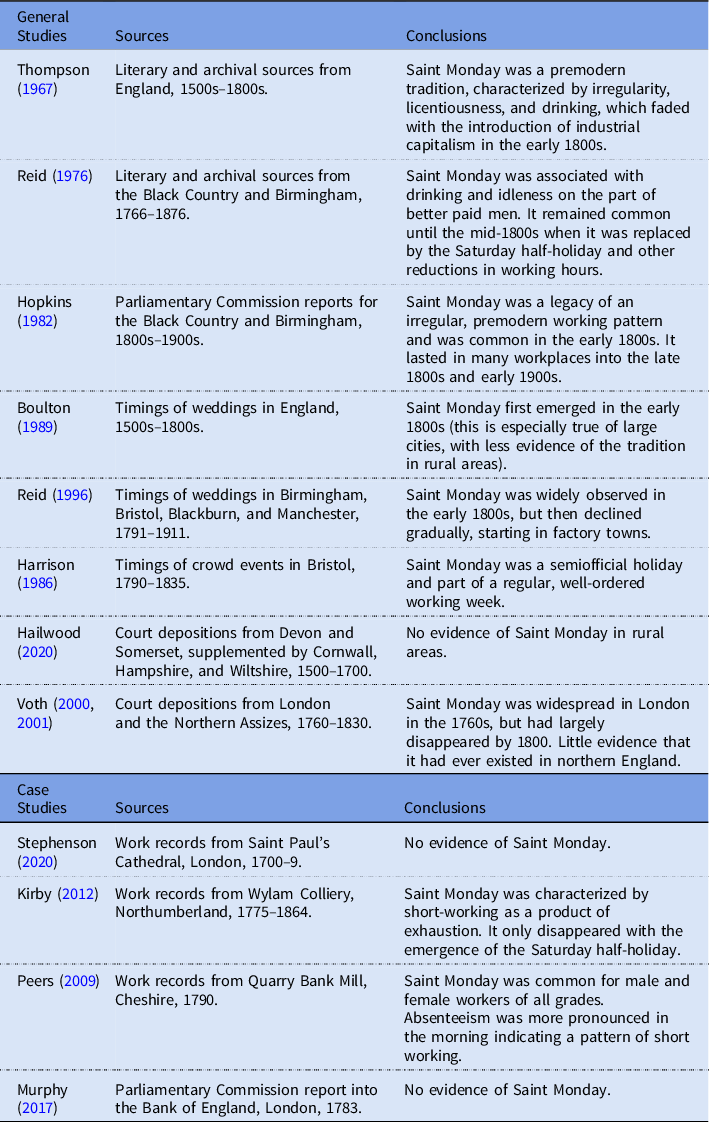

The existing literature therefore leaves us with numerous unresolved debates about the existence, nature, and evolution of Saint Monday (summarized in table 1). Given the type of indirect evidence used in this essay, I will not be able to comment on questions about whether Saint Monday represented premodern irregularity, an official holiday, or something else entirely. However, these catalogs of political events do allow us to test the “orthodox narrative” about its emergence and decline, a narrative that claims that Saint Monday developed in the mid- to late eighteenth century and started to decline in the middle decades of the nineteenth, a process that happened faster in factory towns than elsewhere.

Table 1. Evidence on the existence, evolution, and nature of Saint Monday

If there are significant debates about Saint Monday, then the position of Sunday as a religiously ordained day of rest might be thought to be better established. Indeed, Sundays are the point of continuity at the heart of both the modern weekend and Thompson’s irregular, preindustrial week. However, it is worth noting that religious groups were perennially concerned about the violation of the Sabbath and there were recurring campaigns to defend it, especially from new urban temptations (Roberts Reference Roberts2004). Moreover, recent quantitative research on rural areas in south west England in the early modern period shows that work continued right the way through the week: with no evidence of Saint Monday and almost as much work on Sundays as there was mid-week (Hailwood Reference Hailwood2020: 107).

The available evidence therefore suggests that, between the early modern period and the Industrial Revolution, British workers worked harder. But where those extra days of labor came from is difficult to ascertain. Voth has suggested that a decline in the observance of holidays and Saint Monday in the late 1700s account for the increase. But this runs against a wide range of studies that argue that the tradition of Saint Monday was observed until at least the mid-nineteenth century. The evidence on the observance of the Sabbath and the ordering of the working week is less systematic and therefore harder to summarize, but it is clear that there are significant gaps in our knowledge here too. The purpose of this essay is therefore to add another piece of empirical evidence to these puzzles, using the timings of political events to examine the prevalence of Saint Monday and the structure of the working week over the long nineteenth century.

Data and Methods

The logic behind using crowd events as a proxy for time use is that any event depends on large numbers of people being available: without people, there’s no crowd, and without a crowd, there’s no event. Contemporary social movements are painfully aware of this. To take just two examples, the routine of gilet jaunes activism in France was structured around a regular Saturday morning protest (Harding Reference Harding2019), while across the Middle East, protests are often timed to coincide with the end of Friday prayers (Ketchley and Barrie Reference Ketchley and Barrie2019). Working backward, we can therefore attempt to infer patterns of time use from the timings of events. In particular, this essay uses political events as proxies to examine three aspects of time use in the long nineteenth century: the tradition of Saint Monday, the observance of the Sabbath, and the overall ordering of the working week.

To take one example, in July 1853, a riot took place in Glasgow:

On Monday afternoon, a serious riot occurred in King Street…[.] The row was commenced by a fellow named Peter McBrady, who having quarrelled with the police, took the liberty of knocking down one of their number…[.] Latterly, through the aid of an additional body of police, McBrady was secured and conveyed to the Central Police Office. Before this could be effected however, a disorderly mob of ruffians made a desperate attack upon the police. (Glasgow Sentinel 23/07/1853)

This account reveals that, on a Monday afternoon, there were crowds of people milling around on King Street, who were willing and able to attempt to rescue McBrady from the police. This therefore suggests that Monday afternoons were not a normal time for work. One example would obviously be inconsequential as evidence, but the aim of proxy studies is to amass large catalogs of events and so to provide a quantitative measure of time use over time.

All studies using events as proxies for time use (whether those are weddings, mass phenomena, or religious ceremonies) rely on the assumption that those who participate are representative of the wider working population. In some senses this is a fairly heroic assumption. But there are two reasons to think that, treated cautiously, this approach can bear fruit. The first is that the three catalogs deployed in this essay cover a huge range of different kinds of events: from royalist celebrations to Chartist revolts, bread riots, and meetings of local associations. They should, therefore, capture a fairly wide range of society. Indeed, the impression given by sources is that there was huge variation in the kind of people involved: the young and the old, people from different trades, from various ethnic backgrounds, and even from different classes (for further support of this logic see Harrison Reference Harrison1988: 121–27). However, it is difficult to test this impression in greater detail because the descriptions of the crowd given by most sources are extremely case specific: in industrial riots they refer to people’s trades, in Chartist meetings to their class, in Catholic demonstrations to their ethnicity, and so on. This leads to the second reason to be optimistic about the value of proxy studies: most quantitative assessments of crowd participation for this period confirm these qualitative impressions. In particular, George Rudé’s classic analysis of the “faces in the crowd” shows that they did represent a fairly wide cross-section of working society (Hobsbawm and Rudé Reference Hobsbawm and Rudé1968; Rudé Reference Rudé1956, Reference Rudé1962, Reference Rudé1964).Footnote 5 For those unpersuaded by these arguments, I perform a robustness test in the section “Robustness Test,” repeating key pieces of analysis on a subset of “large” events that ought to be more representative of the wider working population.

This essay relies on three catalogs. The first is a catalog of 2,227 political meetings from northern England between 1790 and 1848 (Navickas Reference Navickas2020). These are taken from records of self-defined public meetings contained in newspapers and local primary sources. The second is a catalog of 414 riots from Manchester, Liverpool, and Glasgow between 1800 and 1939 (Tiratelli Reference Tiratelli2019). Riots are here defined as public, collective violence against people or property involving more than 20 participants, and the catalog was populated using keyword searches of a range of digital newspaper archives (The Annual Register [an annual reference work published in London, 1758–1994], The Times [a daily newspaper published in London from 1785], and all the local newspapers from the three cities included in the British newspaper archive as of August 2016). The third is Charles Tilly’s famous catalog of 8,088 contentious gatherings occurring in southeast England from 1758 to 1820 and in Britain as a whole from 1828 to 1834 (Tilly and Horn Reference Tilly and Horn1988). Contentious gatherings are defined as occasions on which at least 10 persons assembled in a publicly accessible place and either by word or deed made claims that would, if realized, affect the interests of some person or group outside their own number. Again, Tilly’s catalog is drawn principally from newspapers and published annuals.Footnote 6

Each of these catalogs has its own advantages and disadvantages. Katrina Navickas’s catalog of political meetings contains a large number of events from a fairly wide temporal period. However, a large proportion of them come from Manchester and its neighboring towns, a region that is often considered to have been one of the first to transition to the “modern” factory system and “modern” patterns of time use (Reid Reference Reid1996; see also Bohstedt Reference Bohstedt1983). The advantage of the second catalog is that riots are essentially unplanned events, which means that people would not have been able to organize an absence from work in advance. That catalog is also very long, collecting data in a consistent manner over 140 years of history. However, it is the smallest of the three. Tilly’s catalog is the largest and most widely used for the study of popular contention in this period. But it has two noticeable drawbacks: first, the catalog is not consistent as it shifts in geographical scope after 1828; second, it doesn’t contain a record of the time of the event, which makes it impossible to determine whether the event took place inside of normal working hours or not. By combining all three, I hope to be able to mitigate the limitations of each individual catalog.

One more general limitation of the sources is worth mentioning. Previous work has shown that there is substantial variation in time use across different parts of Britain, often as a result of different local economic conditions. In an ideal world, these datasets would record who attended these events and so would allow us to see which workers were out of work at particular times. However, none of the catalogs provide that information (largely because of the difficulties outlined in the preceding text).Footnote 7 In the absence of individual-level data, the next-best option would be to make inferences from the location of the event (as in Reid’s comparison of factory and workshop towns). Two of the catalogs do provide specific locations and so I will make some comparisons, principally between the pioneering industrial economy of Manchester and other more diverse settings. But, unfortunately, Tilly’s catalog of contentious events only provides information on the county in which each event took place, a very large geographic area that would contain many different economic conditions.

In each of the tables that follow, I exclude strikes and turnouts that by definition take place during working hours (in all three catalogs this is a relatively small number of events). I also exclude any events without accurate dates, leaving final sample sizes of 1,452 political meetings, 311 riots, and 5,495 contentious gatherings. These represent events that could in principle have taken place on any day of the week, either inside or outside of normal working hours. As Voth (Reference Voth1998) argues, this approximates (very roughly) the random hour recall method of time-use surveys, giving us a snapshot of whether people were in or out of work at that particular time. However, this data cannot be regarded as a properly random sample and this represents a substantial limitation to my analysis. As such, any conclusions derived from the three catalogs will be necessarily provisional and probably imprecise. Nevertheless, I hope that the general patterns observed in the timings of these political events can enrich the evidential base for studying time use in the long nineteenth century.

Results

Saint Monday

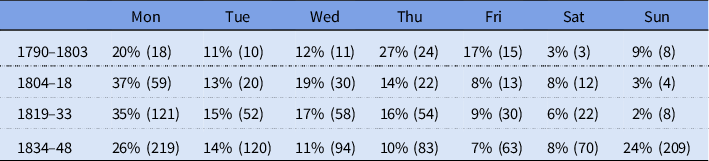

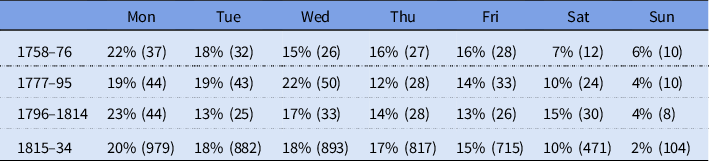

The timings of political meetings in northern England show a strong and consistent preference for meeting on a Monday (table 2). Across the period, the proportion of meetings taking place on that day varies from one in five to nearly two in five, far higher than the one in seven you would expect by random chance. The pattern is also strongest in the first few decades of the nineteenth century, supporting those accounts of Saint Monday that make it coextensive with industrialization (e.g., Hopkins Reference Hopkins1982; Kirby Reference Kirby2012; Reid Reference Reid1976). It also flatly contradicts Voth’s claim that Saint Monday was never widely observed in northern England (Voth Reference Voth2000, Reference Voth2001). The only other days that attract unexpectedly high numbers of meetings are Thursdays between 1790 and 1803, and Sundays between 1834 and 1848. The latter will be dealt with in the discussion of Sabbatarianism that appears in the following text, but the concentration of meetings on a Thursday in that earlier period deserves some comment. These were overwhelmingly loyalist and patriotic meetings, often in honor of royal birthdays or in opposition to republicans and radicals. In fact, the number is inflated somewhat by the four separate celebrations of the king’s birthday, which took place across Carlisle on Thursday June 4, 1801, and the three interconnected loyalist demonstrations in Bradford on Thursday December 20, 1792.Footnote 8

Table 2. Political meetings in northern England by day, 1790–1848 (n = 1,452)

Source: Navickas Reference Navickas2020.

Notes: Percentages are the proportion of meetings taking place on that day per period (counts in brackets).

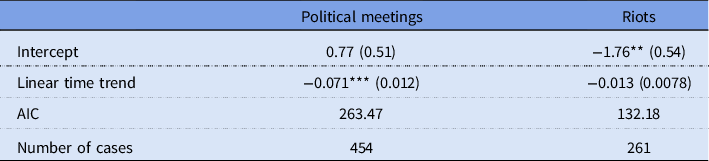

This initial analysis supports the idea that Monday was not a regular day for work in the early nineteenth century. Indeed, the extremely low concentration of meetings on a Saturday also supports Thompson’s description of work rates accelerating throughout the week, building to a frenetic pace on Friday and Saturday (Thompson Reference Thompson1967: 75). But a more stringent test of the popularity and prevalence of Saint Monday requires looking at the proportion of riots taking place on a Monday and inside of normal working hours. Following Voth (Reference Voth2001), I code the normal working day as running from 7 am to 7 pm and restrict the sample to only those meetings that contain a description of the time at which the meeting took place. This reduces the size of the sample considerably (to 454). It is also an inexact science because not all accounts contain a precise timing. In these cases, my procedure was as follows: when the meetings were described as happening in the “afternoon,” “day,” or “morning” they were counted as occurring during working hours; those described as taking place in the “evening” or at “night” were counted as occurring outside working hours. As table 3 shows, before 1818 nearly three in every 10 meetings were arranged for normal working hours on a Monday. This is even higher than the 20 percent that Harrison finds in his catalog of crowd events in Bristol (Harrison Reference Harrison1986). This proportion then drops to less than 1 in 10 for the period between 1819 and 1848. Although the relatively high proportion of events taking place on Monday evenings might indicate a tradition of short working, the overall pattern implies that Saint Monday was on the decline before 1850. Indeed, a simple, bivariate logit regression shows that the log odds of a given meeting occurring during normal working hours on a Monday decreases with each passing year (coefficient: –0.071, p < 0.0001; see appendix table A1).

Table 3. Political meetings in northern England by day and working hours, 1790–1848 (n = 454)

Source: Navickas Reference Navickas2020.

Notes: Following Voth (Reference Voth2001), working hours are counted as 7 am to 7 pm. When the meetings were described as happening in the “afternoon,” “day,” or “morning” they were counted as occurring during working hours. Meetings described as taking place in the “evening” or at “night” were counted as outside working hours. Percentages are the percentage of meetings taking place at that time and day per period (counts in brackets).

These results suggest that the decline of Saint Monday might have started in the early nineteenth century. In fact, after narrowing the analysis to Reid’s classic factory towns, Manchester and Blackburn, this pattern becomes even stronger. In those two towns, the number of political meetings taking place on Monday fell from 55 percent in the 1800s and 1810s, to 18 percent 20 years later. Between 1819 and 1848, the proportion of events taking place on Monday in normal working hours was just 2 percent (looking at all the other towns in the catalog, the figure is 11 percent). These findings therefore corroborate the orthodox narrative, supporting the idea that the decline of Saint Monday started earlier in places where factory work was more widespread.

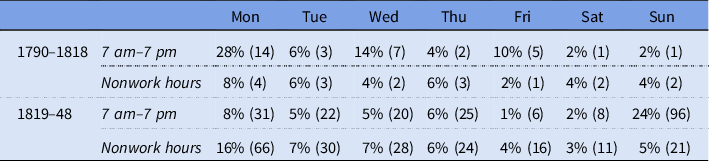

Turning to the catalog of riots in Manchester, Liverpool, and Glasgow, we find further evidence confirming the prevalence of Saint Monday outside of London. Until the 1860s, Monday remained the most popular day for rioting, and was then displaced by a modern Saturday–Sunday weekend (table 4; incidentally, the fact that the modern weekend shows up so clearly in this data should help to reassure readers that these proxies are in fact tracking real changes in everyday time use). This late transition reinforces the orthodox narrative about Saint Monday: that it reached its peak in the early 1800s, before gradually declining.

Table 4. Riots in Manchester, Liverpool, and Glasgow by day, 1800–1939 (n = 311)

Source: Tiratelli Reference Tiratelli2019.

Notes: Riots taking place as part of a strike were excluded. Percentages are the proportion of riots taking place on that day per period (counts in brackets).

Looking again at the precise time of the events (and following the same coding procedure as above), there is a clear reduction in the proportion of riots taking place on a Monday during normal working hours after 1870 (table 5). Again, the high number of riots taking place on Monday evenings in the early period might also point to short working. However, this data needs to be interpreted with some caution because, after dropping riots without any record of the time at which they took place, the number of cases is rather small (falling to 261—more than the 245 events that Harrison analyses, but over a longer period). A bivariate logit regression finds that the log odds of a given riot taking place during normal working hours on a Monday decreases over time (coefficient: –0.013), a finding that approaches but does not meet conventional levels of statistical significance (p = 0.11; see appendix table A1). It’s also worth noting that the decline in Monday rioting happens later in Liverpool and Glasgow than in industrial Manchester—something that mirrors the findings described in the preceding text and lends weight to the idea that the demise of Saint Monday was bound up with the expansion of the factory system and connected movements for a Saturday half-day and restricted working hours.

Table 5. Riots in Manchester, Liverpool, and Glasgow by day and working hours, 1800–1939 (n = 261)

Source: Tiratelli Reference Tiratelli2019.

Notes: Riots taking place as part of a strike were excluded. Following Voth (Reference Voth2001), working hours are counted as 7 am to 7 pm. When the riots were described as happening in the “afternoon,” “day,” or “morning” they were counted as occurring during working hours. Riots described as taking place in the “evening” or at “night” were counted as outside working hours. Percentages are the percentage of riots taking place at that time and day per period (counts in brackets).

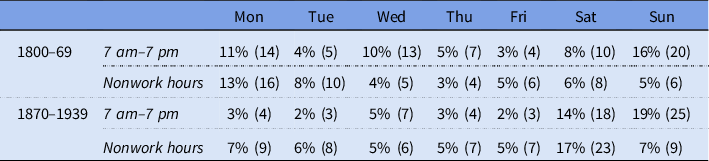

Tilly’s catalog does not suffer from limited sample size, being one of the largest collections of historical events available for the United Kingdom. It is also numerically dominated by events from the county of Middlesex, which covered most of London, and therefore expands the geographic boundaries of this essay. Table 6 shows that contentious gatherings are heavily weighted toward the start of the week: Monday is the most popular day in most periods, and the number of events then declines over the following days, with very few falling on Saturday or Sunday. This supports the idea that work accelerated throughout the week. But the differences between Monday and other weekdays are not particularly high and fluctuate without trend across the period. Given that information on the precise time of gatherings is not available from this catalog, we unfortunately cannot repeat the analysis of working hours performed in the preceding text. This means that evidence from contentious gatherings can only provide qualified support for the idea of a widespread national tradition of Saint Monday. But it does imply that there was some reduction in work early in the week, and that this continued for much longer than Voth’s estimates for the establishment of a six-day week allow.

Table 6. Contentious gatherings in Britain by day, 1758–1834 (n = 5,495)

Source: Tilly and Horn Reference Tilly and Horn1988.

Notes: Strikes and turnouts were excluded from these counts. Percentages are the proportion of gatherings taking place on that day per period (counts in brackets).

Overall, the evidence from these three catalogs supports the orthodox narrative. Saint Monday appears to have been widely observed in the early nineteenth century, including in northern England, with roots possibly stretching back to the 1760s. More significantly, its decline seems to have started earlier in factory towns like Manchester, before spreading to the rest of the country in the middle decades of the nineteenth century.

Sabbatarianism

These three catalogs also give us a window into the observance of the Sabbath in nineteenth-century Britain. The idea that Sundays were a divinely ordained day of rest was a “touchstone of cultural commitment” to Christianity for much of this period (Roberts Reference Roberts2004: 168). And, although never as powerful as the American “Sunday closing” movement that flourished in the 1820s and pioneered new forms of social movement organizing, there was a British movement to counter the “profanation of the Sabbath” from at least the 1790s (Stamatov Reference Stamatov2011). Initial attempts to extend Sunday trading restrictions through legislation were fairly unsuccessful, but the idea that the Sabbath was being profaned by commerce, leisure, and public disorder grew throughout the war years and flourished in the 1820s, where it was linked to wider fears about social stability and cultural degradation (Roberts Reference Roberts2004; see also Bushaway Reference Bushaway1982; Hind Reference Hind1986: 390–91).

The evidence from the catalogs of contentious gatherings and organized political meetings shows that political activists were loath to organize events on a Sunday. Until 1834, it was rare for the proportion of events taking place on the Sabbath to exceed 5 percent (tables 2 and 6). But this changed in the 1830s and 1840s, when Sunday meetings became relatively commonplace (24 percent of meetings in that period took place on a Sunday; see table 2). These Sunday meetings are fairly heterogeneous, including trade union and socialist meetings, and demonstrations at churches and sermons. But one particularly prominent category is Chartist lectures like the following:

MANCHESTER. Mr. James Leach will lecture in the Carpenters Hall, on Sunday, (to-morrow,) at half-past six o’clock in the evening. There will also be a Discussion, in the Large Anti-Room of the above Hall, to commence at half-past two o’clock in the afternoon. Subject “Are the Chartists justified in uniting the Land question with the agitation for the Charter?” (Northern Star 22/07/1843)

It’s important to recognize that the decision by Chartist organizers to violate the Sabbath was not an attempt to usurp the Church and the Sunday Service. Local Chartists instead tended to organize meetings as “additional afternoon or evening meetings, churchyard overspill meetings, or visited friendly churches … with a trusted cleric” (Yeo Reference Yeo1981: 130). In fact, the overlap between Chartism and Methodism may have made Sunday a natural choice of day for radical politics in this period (Lyon Reference Lyon1999; Thompson Reference Thompson1963: 350–401).

The data from the catalog of riots reinforces this impression. The first thing to note from table 4 is that the proportion of riots taking place on a Sunday is significantly higher than for planned events like meetings. This reflects the fact that riots were structured by the simple availability of people, while those organizing meetings also faced public relations constraints and may not have wanted to be seen to be violating the Sabbath. The significance of this concern with optics becomes clear when it is placed in the context of Tilly’s famous account of the evolution of protest in Britain (Tilly Reference Tilly1995, Reference Tilly2008). He argues that between the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, a new form of protesting emerged: the modern social movement, with its particular repertoire of protest and its displays of worthiness, unity, numbers, and commitment. Given the central role that religious movements played in pioneering these new forms of protest, it should not be surprising that political organizers were keen to be seen to be upholding moral shibboleths and thus proving their respectability and their “worthiness” (Stamatov Reference Stamatov2011; Tilly Reference Tilly1995: xix).

The second point to note in table 4 is that the proportion of riots taking place on a Sunday increases into the twentieth century. This suggests that the profanation of the Sabbath became more common over time, and that the pattern seen in the data for political meetings from the 1830s and 1840s reflects a wider shift in attitudes toward the Sabbath, rather than something particular to the Chartist movement and their religious connections. Whether the Chartists’ preference for Sunday meetings was a cause of that shift, or a reflection of it, is difficult to ascertain. The most plausible argument is probably that it worked to accelerate a preexisting trend.

The Ordering of Time

The question of the ordering of the working week is difficult to test for two reasons. First, although the phrase is widely used, it is rarely explicitly operationalized. Here, I interpret a well ordered week as one in which all events occur in their designated place. Simplifying somewhat, a perfectly ordered week would be one in which all political events took place on the same day and at the same time. Orderedness can then be operationalized as a measure of inequality. The second challenge is that the phrase is often used in the absolute. For example, Harrison claimed that the working week in early-nineteenth-century Bristol was ordered but didn’t assess how ordered it was compared to other times or places (Harrison Reference Harrison1986). This matters because it is hard to imagine any human behavior that is completely randomly distributed across time or space. And, if some form of ordering is commonplace, then the crucial question is the comparative one: how ordered is this or that phenomenon. I can only begin to address these two issues here and a huge amount of research will need to be done before we can reach any firm conclusions about how ordered time was in Britain in this period. Nevertheless, we can make a start by looking at the distribution of political events from 1758 to 1939.

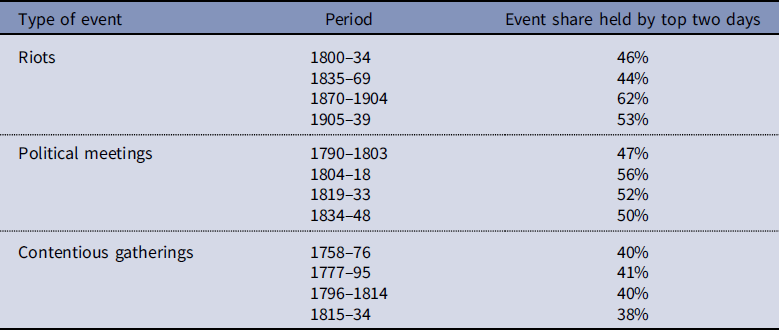

In terms of the ordering of the working week, the evidence is mixed. Although the percentage of riots taking place on the top two days of the week increases over the nineteenth and early twentieth century, there is no clear trend in the distribution of political meetings or contentious gatherings (table 7). This suggests, although the evidence is necessarily tentative, that the working week became more regular in the latter half of the nineteenth century, but not before.

Table 7. Political events and the ordering of the working week, 1758–1939

Sources: Tilly and Horn Reference Tilly and Horn1988, Navickas Reference Navickas2020, and Tiratelli Reference Tiratelli2019.

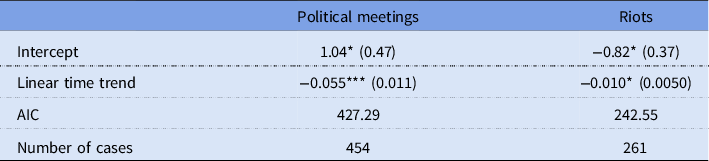

Firmer evidence can be found for the ordering of the working day. The timings of meetings and riots reveal sharp declines in the number of events taking place during normal working hours (tables 2 and 4). In fact, bivariate logit regressions show that the log odds of a given event taking place during normal working hours between Tuesday and Friday (days that were definitely normal working days) decrease with each passing year (Meetings: –0.055, p < 0.0001; Riots: –0.010, p = 0.038; see appendix table A2). Taken together, this indicates that the working day became more clearly demarcated as the nineteenth century wore on and that, while the working week may have had a discernible shape by 1800, its boundaries became more firmly established over time.

Robustness Test

To address concerns about whether participants in political events were representative of the wider working population, I repeat several key pieces of analysis on a subset of “large” events (working on the assumption that an event with more participants is like a survey with a larger sample size). This presents two additional challenges. The first is that newspaper estimates of the number of participants (which is where most of the information in these catalogs comes from) are notoriously imprecise. Second, data on the number of participants is only available for two of the catalogs and for a small subset of events (6 percent of Navickas’s political meetings and 21 percent of Tilly’s contentious gatherings). This considerably reduces the number of events available for analysis. I then restrict the analysis to three subsets of “large” events: those with at least 100, at least 500, and at least 1,000 participants. The results from this robustness test are encouraging. Looking first at large political meetings, I find a high proportion of events taking place on a Monday (between 30 and 40 percent depending on the cutoff point used to determine “largeness”). I also reproduce the finding that the number of events taking place on a Sunday increases in the 1830s and 1840s. Unfortunately, the number of cases with data on the precise time of an event as well as the number of participants is too small to allow for meaningful analysis of whether they took place during normal working hours and whether the working day became more firmly bounded over time. Turning to the second catalog, large contentious gatherings also cluster on Mondays, with very few events taking place on a Saturday or Sunday. Overall, this robustness test therefore reinforces my support of the orthodox narrative about Saint Monday, and my claims about the decline of Sabbatarianism in the Chartist period.

Conclusion

Our understanding of the patterns of time use in eighteenth and nineteenth century Britain has improved considerably since E. P. Thompson’s pioneering work in the late 1960s. However, the difficulty in finding accurate and systematic records of time use means that there are many areas of uncertainty and many unresolved debates. This essay supplements the body of evidence in this area, using political events as proxies for time use over the long nineteenth century. This reveals three patterns. First, it provides evidence supporting the orthodox narrative about Saint Monday against Voth’s critique. The timings of meetings, riots, and gatherings suggest that, in the early nineteenth century, Mondays would find many people out of work across the country. This tradition was waning in some industrial towns by the 1820s, with the rest of the country following a few decades later. Second, while the pattern of rioting shows that Sundays were often a day of rest, political organizers were clearly reluctant to openly call on their supporters to violate the Sabbath by deliberately hosting political events on that day. However, this changed during the 1830s and 1840s, perhaps facilitated by the close connections between Chartism and radical Christianity. Third, these catalogs suggest that the working week and the working day became more structured over the nineteenth century, although this is the most speculative of the three conclusions. An operationalizable definition of “orderedness” should, however, help to facilitate future research on that question.

There are three limitations to my analysis that deserve to be noted explicitly. First, the event catalogs used here are proxy measures and may be biased by various local traditions in the organization of politics. This means that any conclusions derived from the patterns of political events need to be compared against alternative sources. I have tried to do so in the discussion in the preceding text, but new evidence will no doubt continue to change our understanding of time use in this period. Second, as these sources are largely derived from newspapers, they do not allow us to draw any conclusions about people’s own comprehension of time and their practices of time-telling. These subjective dimensions play a key role in Thompson’s portrait of the temporality of industrializing Britain and, again, would merit further study. Third, this analysis does not distinguish between men and women. Due to the nature of the proxy events used in this essay,Footnote 9 we should probably assume that these results largely reflect men’s experience and that there is no reason to suppose that what was true for men was also true for women.

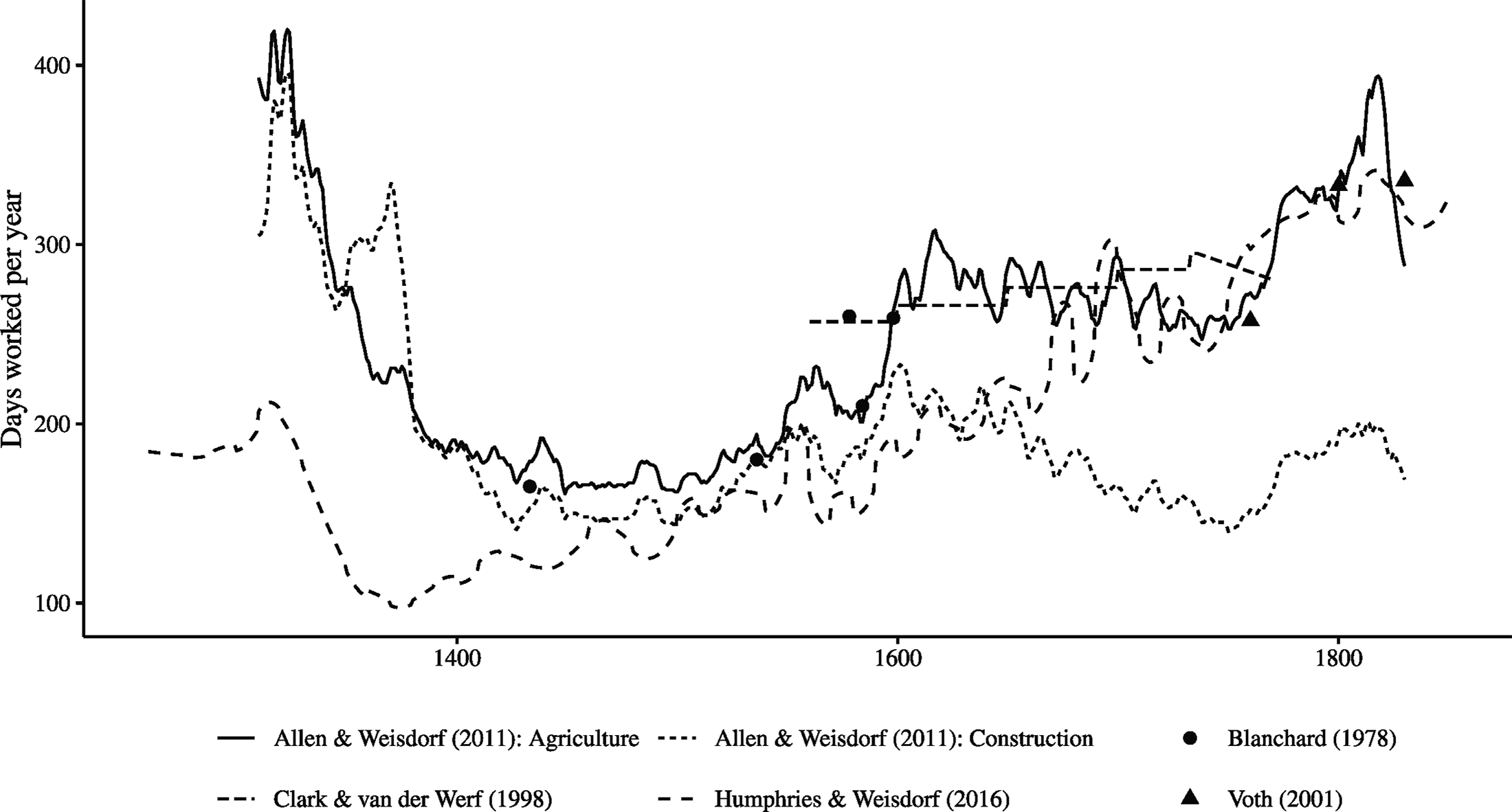

Putting the main findings of this essay in the context of the wider literature on time use and industrialization also raises some significant questions. A variety of different estimates of total labor input find that people were working harder in the centuries leading up to the Industrial Revolution, and especially in the period between 1750 and 1800 (see figure 1; the major exception is Clark and van der Werf Reference Clark and Van Der Werf1998). Although there are three potential sources of increased industriousness (working more intensely, working longer hours per day, working more days per year), the importance of the decline of Saint Monday to Voth’s argument leaves us with a puzzle. If Saint Monday was in fact gaining popularity over the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, then where did those extra working hours come from? I cannot attempt to solve that puzzle here, and Voth does also draw attention to a decline in religious holidays, but this is clearly an area that requires further research.

Figure 1. Estimates of days worked per year in England, 1260–1850.

Sources and notes: Allen and Weisdorf (Reference Allen and Weisdorf2011) estimate the total number of working days needed to purchase a basket of goods for agricultural laborers in Southern England and builders in London; Blanchard (1978) estimates days worked per year for English miners; Clark and van der Werf (Reference Clark and Van Der Werf1998) assume perfect arbitrage and divide the annual salary by the day wage for agricultural laborers in Britain; Humphries and Weisdorf (2016) repeat the arbitrage calculation for a larger sample of annually and casually contracted workers in different trades across Britain; and Voth (Reference Voth2001) estimates days worked on the basis of court records and witness accounts from London and northern England.

Finally, answering these questions may have implications beyond the remit of specialist historians. In recent years, debates have raged over the temporal effects of digital technology, the demise of the 9–5, the erosion of barriers between work and leisure, and the persistence of women’s “second shift” (Gershuny and Sullivan Reference Gershuny and Sullivan2019). Revisiting these historic debates about the effects of industrialization on time use could therefore provide us with important clues for analyzing the impact of the technological and social revolutions of the twenty-first century.

Table A1. Log odds of a given event occurring on a Monday during normal working hours (7am - 7pm)

Sources: Navickas (Reference Navickas2020), Tiratelli (Reference Tiratelli2019)

Notes: Coefficients are in log odds form with standard errors in brackets. Linear time trend is set to 0 for the first year in each catalogue. Estimated via logit regression.

*** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05.

Table A2: Log odds of a given event occurring during normal working hours (7am - 7pm) between Tuesday and Friday

Sources: Navickas (Reference Navickas2020), Tiratelli (Reference Tiratelli2019)

Notes: Coefficients are in log odds form with standard errors in brackets. Linear time trend is set to 0 for the first year in each catalogue. Estimated via logit regression.

*** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05.