1. Introduction

Since the early days of computational linguistics, research in natural language generation (NLG)—traditionally characterised as the task of producing linguistic output from underlying nonlinguistic data—has often been considered as the ‘poor sister’ in relation to work in natural language understanding (NLU). Over the years, a variety of reasons have been offered as to why this might be the case, such as a perception that NLG is comparatively easy, and so not a problem requiring significant attention. Or, in a similar vein but with a little more nuance, the view that to do NLU satisfactorily you have to understand every way that something might be said, whereas to do NLG, you only need to find one way to say something. Or the observation that, at least until recently, there was a whole lot of text out there that could profitably be subject to automated interpretation, but there was not a whole lot of data demanding explanation.

Whatever the reason, NLG was for a long time a niche interest. I have not carried out a detailed analysis of the papers published in worthy venues over the last few decades, but I think a reasonable guess is that, averaged over the years, only around 10–15% of the papers published in NLP conferences and journals are concerned with generating language, whereas 85–90% are concerned with language understanding. The predominance of NLU work has been so great that, for many people, the term ‘Natural Language Processing’ is synonymous with ‘Natural Language Understanding’, silently disenfranchising those who might want to do language processing in the other direction.

As it is in the research world, so it is in the commercial world. It is only in the last 7 or 8 years that NLG has achieved some commercial prominence, although there were in fact earlier entrepreneurial experiments, as we will review below. But today, although it remains a small part of the overall commercial NLP market, NLG is a recognised industry sector. If you want a sign of such recognition, look no further than global research and advisory firm Gartner, whose first ‘Market Guide for Natural Language Generation Platforms’ was released in 2019. There is no doubt that there are real use cases out there for NLG technology, and people are willing to pay for them.

So how did we get here, just exactly where is ‘here’, and where are we going?

2. The early days

I mark the point of entry of NLG into the mainstream media consciousness as an article published in Wired magazine on 24 April 2012. Entitled ‘Can an Algorithm Write a Better News Story Than a Human Reporter?’, this showcased Chicago-based NLG company Narrative Science and its work in creating sports and finance stories from underlying datasets. The story has been cited and linked to many times since by journalists writing about NLG.

But Narrative Science, founded in 2010, was not the first company to attempt the commercialisation of the technology. That credit probably goes to CoGenTex, founded in 1990 by Dick Kittredge, Tanya Korelsky and Owen Rambow. With a strong theoretical basis in Igor Mel’uk’s Meaning-Text Theory, the company’s most widely known work involved bilingual generation of English and French texts; its FoG weather report generation system was arguably the first operationalised NLG application. Producing multilingual output has often been seen as a great use case for NLG, on the assumption that it is less risky to generate output in different languages from a single common input than to generate one language and then use machine translation on the output to get the others.

There were other attempts to produce commercially viable NLG applications during the 1990s, most notably in the context of form letter generation: both Stephen Springer with his colleagues at Cognitive Systems in the USA and JosÉ Coch at GSI-Erli in France built applications whose purpose was to automate the production of fluent tailored responses to customer queries and complaints—a process that was massively time consuming for humans, with considerable variation in output quality, but fairly straightforward for an automated tool.

But looking back today, these attempts at commercialisation were pretty much just fleeting blips on the radar. If you wanted to invest in language technologies in the 1990s, you would be wiser to put your money into information extraction or speech recognition.

3. The data-driven wave

Fast forward: by the time the earlier-mentioned Wired article appeared, things had changed considerably. In particular, five companies that are now the most visible in the commercial NLG space had either been formed or were on the verge of being founded. In order of appearanceFootnote a:

• Ax Semantics: founded 2001 in Germany; raised US$6m; https://en.ax-semantics.com.

• Yseop, founded 2007 in France; raised US$12.8m; https://www.yseop.com.

• Automated Insights, founded 2007 in North Carolina; raised US$10.8m prior to being acquired in 2015; www.automatedinsights.com.

• Narrative Science, founded 2010 in Chicago; raised US$43.4m; www.narrativescience.com.

• Arria NLG, founded 2013 in the UK based on an earlier company called Data2Text; raised US$40.3m; https://www.arria.com. Footnote b

The market offerings of these companies tend to fall into two streams. First, as in many other technology domains, it is common for the vendors to offer bespoke application development via a professional services model: the customer believes they have a problem that can be solved with NLG, and the vendor will build and maintain the corresponding solution for them. Second, generally developed on the basis of learnings and experience acquired from activity in the first stream, it is common for the vendors to offer self-service toolkits that third parties can use to develop their own applications, typically these days via a SaaS model.

Making money under the first stream is a challenge for a new technology area, because rational price points are not well established, and companies risk either underbidding to get the business or scaring away the customer with sticker shock. Plus, it is hard to scale a professional services business, which risks scaring away investors. Making money under the second stream can be tricky too because it demands significant skill in both user interface and general product design. It is not unusual for a customer to optimistically attempt their own development using the vendor’s toolkit, find it is just too hard to achieve the results they want and return to the vendor with a request to engage their professional services team after all.

Of course, the particular mix of these two streams of activity offered by any given vendor varies. Ax Semantics appears to have gone the self-service toolkit route from very early on. Automated Insights offered free trial usage of its Wordsmith NLG platform in 2014, following which there were rumours (subsequently unfulfilled, as far as I can tell) that Narrative Science’s Quill product would be made accessible to third parties in a similar fashion, and Arria introduced its self-service NLG Studio tool around 2017. With the exception of Ax Semantics, who have for a long time provided extensive publicly accessible online documentation, most vendors have tended to be just a little shy about revealing too much about what their technology actually looks like and how it works. Typically, there will be a requirement to sign up for a demo and interact with a salesperson, perhaps based on the vendor’s fear that, unchaperoned, the naked body under the sheets will not be quite as attractive to the customer as they have been led to expect.

Functional transparency has increased significantly, though, with the more recent integration of NLG capabilities into business intelligence (BI) tools. An objection to the adoption of NLG technology frequently encountered by any NLG salesperson is summed up in the popular clichÉ that a picture is worth a thousand words, and it is certainly clear that if you just want an easy-to-absorb presentation of how a stock price has changed over time, for example, then it is hard to beat a line on a graph. There are, of course, a variety of arguments you can make for text over graphics, but at the end of the day, life’s too short for tight shoes: it makes most sense to take the path of least resistance by giving the customer both text and graphics.

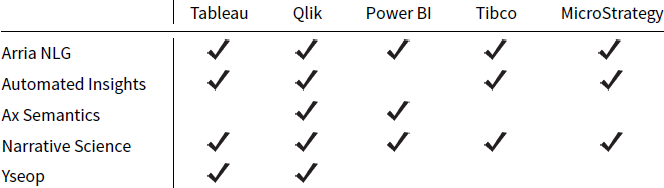

But in order to do that you face a problem: your customers are already used to the pixel-perfect graphics produced by the likes of Tableau and that sets the bar very high indeed. The response to that challenge? If you cannot beat them, join them. And thus we have the advent of NLG plug-ins for BI platforms: what might be considered a multimodal marriage made in heaven. Arria NLG, Automated Insights and Narrative Science have been at the forefront of this move. Here is a wee table that shows which NLG vendors offer, or have offered – sometimes the current status of the product is unclear – integration with each of the main BI tools.

This is, to the best of my knowledge, up to date at the time of writing, but it stands a good chance of being out of date by the time you read this, since the vendors appears to be actively competing on this dimension.

Not represented in this table are other integrations that the NLG vendors have attempted to leverage – and there are quite a few, since piggybacking your tool on platforms that already have a large user base is a very sensible user acquisition strategy. In the early days of its Wordsmith product, Automated Insights offered an Excel plug-in, as did Yseop with its Savvy product. More recently, Arria has announced a similar forthcoming integration. Narrative Science, meanwhile, has developed Lexio, a tool which produces business newsfeeds from Salesforce data. Ax Semantics offers integrations with a number of e-commerce platforms, which speaks to their business origins, whereas all the others see various kinds of financial reporting as key use cases for NLG, Ax Semantics has historically been more focussed on the automation of product descriptions from databases.

To the extent that you can tell from the clues to functionality that are surfaced by these various products, all the tools are ultimately very similar in terms of how they work, which might be referred to as ‘smart template’ mechanisms. There is a recognition that, at least for the kinds of use cases we see today, much of the text in any given output can be predetermined and provided as boilerplate, with gaps to be filled dynamically based on per-record variations in the underlying data source. Add conditional inclusion of text components and maybe some kind of looping control construct, and the resulting NLG toolkit, as in the case of humans and chimpanzees, shares 99% of its DNA with the legal document automation and assembly tools of the 1990s, like HotDocs (https://www.hotdocs.com). As far as I can tell, linguistic knowledge, and other refined ingredients of the NLG systems built in research laboratories, is sparse and generally limited to morphology for number agreement (one stock dropped in value vs. three stocks dropped in value).

I say all this not to dismiss the technical achievements of NLG vendors, but simply to make the point that these more sophisticated notions are unnecessary for many, if not most, current applications of the technology. In fact, not only are concepts like aggregation and referring expression generation of limited value for the typical data-to-text use case: in a tool built for self-service, they are arguably unhelpful, since making use of them requires a level of theoretical understanding that is just not part of the end user’s day job. Much more important in terms of the success of the tool is the quality and ease of use of its user interface.

But if you are an NLG vendor who is offended by this characterisation and you do indeed make use of sophisticated linguistic processing in your toolset to achieve something that would be otherwise difficult or painful, then please accept my apologies. I could not find the evidence of that on your website, but if you would like to drop me an email and arrange a demo of said capability, I will eat my hat and update this piece accordingly in its next iteration.

Aside from the five most prominent players mentioned above, there are now a considerable number of other NLG vendors active in the space. The following list is unlikely to be exhaustive, and I would be grateful to be told of any companies focussing on NLG that I have missed:

Infosentience (https://infosentience.com), founded 2011 and based in Indiana: appears to be focussed on sports reporting, but their website does suggest some other use cases have been addressed.

Linguastat (http://www.linguastat.com), founded 2005 and based in San Francisco; focusses on product descriptions.

Narrativa (https://www.narrativa.com), founded 2015 and based in Madrid, with offices in the United Arab Emirates; sees its target market as consisting of the usual suspects: financial services, e-commerce, healthcare and telecoms.

Phrasetech (https://www.phrasetech.com), founded in 2013 and based in Tel Aviv: their website suggests that their technology has rich theoretical underpinnings, so I am hoping they will be provoked by my challenge above.

Retresco (www.retresco.de), founded in 2008 and based in Berlin: the case studies on their website describe applications in product description, real estate, sports reporting, traffic news, and stock market reporting.

Textual Relations (https://textual.ai), founded in 2014 and based in Sweden: focusses on product descriptions, producing output in 16 languages.

VPhrase (https://www.vphrase.com), founded in 2015 and based in India: their website describes a large set of case studies across a range of industries and claims multilingual capabilities.

2txt (https://2txt.de), founded in 2013 and based in Berlin: primary focus is product descriptions.

Based on the information and examples provided on these vendors’ websites, I suspect in most cases their underlying technology is similar in concept to that used by the five major players. Textual relations may be an exception here, since multilingual output is one place where linguistic abstractions might be expected to be of value.

4. The neural revolution

So, today’s commercial NLG technology appears to be relatively simple in terms of how it works. Nonetheless, there is a market for the results that these techniques can produce, and much of the real value of the solutions on offer comes down to how easy they are to use and how seamlessly they fit into existing workflows.

But in terms of underlying technology for generating language, there is of course a new kid on the block: neural text generation, which has radically revised the NLG research agenda. The most visible work in this area is represented by OpenAI’s GPT-2 transformer-based generator, the announcement of which, along with an initial refusal to publicly release the full trained model, led to some controversy in early 2019. Was OpenAI being sincere when it claimed it had results so good that it was fearful of their misuse in disinformation campaigns? Or was it just trying to generate media hype by making such a claim? We will probably never know.

But it is fun to play with. In text generation mode, you give GPT-2 some seed text, and it will continue your text for you. You can try it out at https://talktotransformer.com. Lots of journalists did. The Economist challenged GPT-2 with a youth essay question on climate change and assessed the results.Footnote c The New Yorker Magazine explored whether GPT-2 could learn to write for the magazine.Footnote d

Sometimes the results produced by GPT-2 and its ilk are quite startling in their apparent authenticity. More often than not they are just a bit off. And sometimes they are just gibberish. As is widely acknowledged, neural text generation as it stands today has a significant problem: driven as it is by information that is ultimately about language use, rather than directly about the real world, it roams untethered to the truth. While the output of such a process might be good enough for the presidential teleprompter, it would not cut it if you want the hard facts about how your pension fund is performing. So, at least for the time being, nobody who develops commercial applications of NLG technology is going to rely on this particular form of that technology.

At least, not for the free-to-roam ‘street dog’ version of text generation exemplified by the GPT-2 demo mentioned above. But put the neural NLG puppy on a short leash and things start to get interesting. This is what Google has done with Smart Compose, which tries to predict what you might say next as you type an email. If you have not already experienced this, or do not have access to Gmail, there are a number of demos easily locatable on the web.Footnote e LightKey (https://www.lightkey.io) goes further and offers full-sentence predictions, ‘allowing you to compose emails four times faster, with confidence’. Well, I am not sure about the confidence bit: Google had to add a filter to prevent the gender-biased generation of pronouns.Footnote f

Nonetheless, I believe this is a better indicator of where we will see neural NLG start to provide commercial utility: the augmentation of human authoring. The same technology can be used to offer predictions as to what to write next, or to make suggestions for alternatives for what has already been written. And so Microsoft has recently introduced an AI-driven ‘Rewrite Suggestions’ feature in its Editor product.Footnote g And QuillBot offers a product that uses AI to suggest paraphrases, recently raising over $4M in seed funding. You can try out their technology on their website at https://quillbot.com.

Of course, human authoring has been augmented by tools like spelling correctors and grammar checkers for decades. But what is interesting about these more recent developments is that, to reuse a distinction that will be familiar to researchers in NLG, we have transitioned from having the machine offer suggestions about how to say something to a situation where the machine offers suggestions about what to say.

There are risks here: I am reminded of a recording of a voice call I once listened to of a customer ordering a pizza via a telephony-based spoken-language dialog system, where, after several iterations of the system misrecognising ‘no anchovies’ as ‘with anchovies’, the worn-down customer gave up and accepted the system’s interpretation in preference to her own request. It is easy to imagine contexts where, through laziness, inattentiveness or indifference, you might accept the system’s suggestion even if it does not express the original intention you had in mind. Will ‘it wasn’t me, the computer wrote it’ become a legal defence?

Conscious that neural text generators might be good enough to produce C-grade essays, a piece in The Conversation argued that banning the software would be a losing battle, and that it would be more productive to allow students to use the technology to generate first drafts.Footnote h Hmm, but if you only care about getting a pass grade, why would you bother with revision? Here I am reminded of SciGen, the 2005 experiment run by a trio of MIT students who got a computer science conference to accept a nonsense paper written by their language-model-based algorithm.Footnote i

Notwithstanding these concerns, I think this is where the future lies: intelligent co-authoring, where the machine breaks through writer’s block by offering suggestions as to where to go next, while always being under your control. In the end, it would not matter whether the word you chose was the one that you typed, or an alternative that you selected from the machine’s offerings.

5. Conclusions

There are other uses of modern NLG technology that we have not touched on here. For example, companies such as Persado (https://www.persado.com) and Phrasee (https://phrasee.co) use machine learning to determine the most effective copy for email subject lines and other advertising text; apps like Microsoft’s Seeing AI provide automatically generated descriptions of imagesFootnote j and there are a variety of ways in which NLG is being used in chatbots. But we will leave those themes for another time.

In the above, we have distinguished two quite different NLG technologies. Today’s commercial NLG technology, as used for converting data into text, is conceptually very simple. But despite that simplicity, it is effective and clearly able to provide the basis for a number of viable businesses. This technology base will doubtlessly persist into the future because it provides utility for those who are blind to tables of numbers, or who find it useful to have a verbal delivery of the insights embodied in complex datasets.

Tomorrow’s NLG technology, however, is a completely different beast, which will see its application in quite different contexts. In particular, neural NLG is set to redefine our notion of authorship. Back in 2012, the journalist who wrote the Wired article mentioned earlier asked Kris Hammond of Narrative Science to predict what percentage of news would be written by computers in 15 years. With an understandable reluctance to become a hostage to fortune, Hammond eventually suggested ‘More than 90 percent’. Today, 8 years later and halfway towards the prediction horizon, that looks perhaps a little optimistic. But ask what proportion of texts might be co-authored with machine assistance in even the next 5 years, and I would bet we are looking at a very big number.