1. Labor market divides, risks and policy preferences

While earlier literature on the welfare state pitted a homogenous labor movement against capital, more recent political economy accounts have shown that different parts of labor may not have similar policy preferences (e.g., Rueda Reference Rueda2007; Schwander and Hausermann Reference Schwander and Hausermann2013; Rovny and Rovny Reference Rovny and Rovny2017; introduction, this symposium). Different workers may face distinct risks of becoming unemployed and may as a result develop divergent labor market policy preferences.

However, there remains disagreements concerning how best to conceptualize and operationalize the difference between insiders and outsiders (Marx and Picot, this symposium). On the one hand, the labor market status approach posits that workers are separated into different segments along contractual lines (e.g., Rueda Reference Rueda2007; Vlandas Reference Vlandas2013). Insiders in permanent full-time employment tend to be protected from the risk of becoming unemployed by employment protection legislation, whereas outsiders are either unemployed or in insecure temporary contracts. This in turn shapes differences in individual policy preferences—for instance, insiders are found to favor much less generous unemployment benefits than outsiders.

On the other hand, the occupational unemployment approach contends instead that the risk of unemployment in different occupations constitutes the key determinant of preference formation (Rehm Reference Rehm2009; Rehm Reference Rehm2011; Schwander and Hausermann Reference Schwander and Hausermann2013, Rehm Reference Rehm2016). In this view, workers in a high-unemployment occupation would be outsiders and would therefore develop distinct policy preferences from workers in low-unemployment occupations, regardless of their contractual status.

These two approaches are generally assumed to rely on alternative proxies of who the outsiders are but there is no a priori reason to expect them to be mutually exclusive measures of labor market risk. I argue that status and occupation capture complementary dividing lines in the labor market because they capture distinct types of risks. Labor market status focuses on the different risks that employed and unemployed workers face, whereas the occupational approach focuses on the different risks that both the employed and unemployed in different occupations face. The former therefore emphasizes how current labor market status shapes risk while the latter approach uses occupational unemployment to derive a measure of future risk that cuts across insiders and outsiders. The occupational approach lumps together the employed and unemployed in a given occupation, whereas dualization theory posits a divergence between the interests of employed and unemployed individuals regardless of their occupations.

Conceptualizing these two approaches as complementary rather than substitutes has important implications for our understanding of policy preferences in post-industrial labor markets. We should expect that (1) the unemployed and temporary workers have more pro-outsider policy preferences than permanent workers; and that (2) workers in high-unemployment occupations have more pro-outsider policy preferences than those in low-unemployment occupations. Finding support for both propositions in the same empirical model is necessary to show that both approaches have explanatory power.

The rest of this article investigates empirically the effect of labor market status and occupational unemployment on individual policy preferences. In doing so, it addresses four empirical questions. First, are the variables capturing both approaches statistically significant? Second, what is the magnitude of the effect of these variables on labor market policy preferences? Third, does this magnitude vary depending on the labor market policy preference under consideration? Fourth, how do the variables capturing both approaches interact?

2. Public opinion data on individual policy preferences

To test the empirical relevance of both approaches I rely on a cross-national survey comprising the four waves on the “role of government” compiled by the International Social Survey Program (ISSP Research Group, 2008). My analysis covers 17 countries (see Online Appendix for details) for which there is relevant data at four points in time (1985, 1990, 1996 and 2006). I construct three binary dependent variables that capture labor market policy preferences using respondents’ agreements with the following three statements:

1. “Government’s responsibility to provide a decent standard of living for the unemployed;”

2. “Government’s responsibility to provide a job for everyone who wants one;”

3. “Government should spend more money on the unemployed.”

The first two dependent variables are recoded 1 if the respondent answers “definitely should be” or “probably should be”, and 0 otherwise. The third variable is recoded 1 if the respondent answers “spend much more” or “spend more”, and 0 otherwise. Several independent variables are included to reflect the different ways of measuring labor market risks of the two approaches discussed above. To capture the status approach, two binary variables are created: the first takes value 1 if the respondent is unemployed, and 0 otherwise; the second takes value 1 if the respondent is in part-time work, and 0 otherwise. It is also conceivable that the status of the spouse matters, so I create a variable “spouseinsider” which is equal to 1 if the spouse of the respondent is in full-time employment, and 0 otherwise. To capture the occupational approach, a measure of occupational unemployment is included.Footnote 1 I expect respondents that are currently unemployed and/or in high-unemployment occupations to hold more pro-outsider policy preferences. My empirical analysis controls for a range of factors identified in previous literature: gender and age because younger and female respondents should be more favorable to labor market policies given their higher exposure to unemployment; education (in years) to capture the level of skills of the respondent; union membership; and the occupation of the respondent.

3. The determinants of individual labor market policy preferences

I run a logistic regression analysis which includes country fixed effects to account for unobservable country heterogeneity and reports robust standard errors clustered by country. To assess the relative importance of each independent variable, I plot the semi-standardized coefficients of the logistic regression (i.e., coefficients are rescaled by the standard deviation of the variable in the data). The line around the point estimate represents the 95 percent confidence interval. A positive coefficient suggests the independent variable increases the probability of the dependent variable being 1, or in our case the probability of the respondent having pro-outsider policy preferences.

The results shown in Figure 1 suggest that occupational unemployment and being unemployed both have large positive effects on the probability of having pro-outsider policy preferences but the magnitude of the effect depends on the dependent variable under consideration. Occupational unemployment has the smallest effect on wanting governments to provide for unemployed living standard and the largest effect on wanting governments to provide jobs for everyone. By contrast, being unemployed has a smaller effect on wanting governments to provide a job for everyone than for the other two dependent variables. This is consistent with the notion that the two approaches represent distinct dividing lines: high-occupational unemployment makes you most concerned about jobs, while being unemployed makes you most concerned about the standard of living of the unemployed.

Figure 1. The determinants of labor market policy preferences.

Being female has a much stronger positive effect on “jobs for everyone” than the other two dependent variables, and having an insider spouse negatively affects preference for benefits especially strongly. Two variables are not statistically significant: respondents in part-time work do not have significantly different policy preferences and the variable capturing the respondent’s education is not statistically significant. Finally, being a union member is associated with higher support for pro-outsider policies.

Next, I include in the analysis the occupation of the respondents, whether respondents are married, and whether respondents work in the public sector. Given the surprising non-significant result for years of education in Figure 1, I use instead a crisper—binary—variable capturing whether the respondent has no secondary education. I focus on one dependent variable—whether the government should spend more on unemployment benefits—both for reasons of space and because it captures most accurately support for pro-outsider policies.

The results are shown in Figure 2. Occupational unemployment, being unemployed and being female remain statistically significant while union membership does not. Having no secondary degree has a statistically significant positive effect on the probability of supporting greater government spending on unemployment benefits, while being in part-time work remains statistically insignificant. Being married or in the public sector has no effect.

Figure 2. The occupational determinants of labor market policy preferences.

When assessing the effect of different occupations, I do not include occupational unemployment which would risk being collinear. Plant and machine operators, as well as those in elementary occupations and craft workers, are all more likely to agree that governments should spend more on unemployment benefits. These findings are consistent with the notion that workers with more specific skills—i.e., skills that are less easily transferred to other companies/sectors—have strong pro-unemployment benefits preferences (e.g., Iversen and Soskice Reference Iversen and Soskice2001).

However, the effect for these three occupations is not much stronger than for service workers and clerks which tend to have lower skill specificity. These mixed results reflect an important difference between the status and occupational approaches on the one hand, and the skill specificity approach on the other. Whereas the former two have direct risk implications, the effect of skill specificity is more theoretically ambiguous. Specificity affects both the value of the worker to the employer (because the employer co-invested in the specific skills) and the vulnerability of the worker to unemployment (because the worker co-invested in non-transferable specific skills). The risk of skill-specific workers further depends on the type of capitalism (Hall and Soskice, Reference Hall and Soskice2001): coordinated market economies (CMEs) have institutions in place, such as unemployment benefits and dismissal protection, which reduce the risk for workers of investing in specific skills. At the same time, there may be a higher demand (and higher return) for specific skills in CMEs than elsewhere. Given these complex theoretical expectations, it is perhaps not surprising that the results may be more about the level than the specificity of skills: there is, for instance, a strong effect for elementary occupations, which have low but general skills.

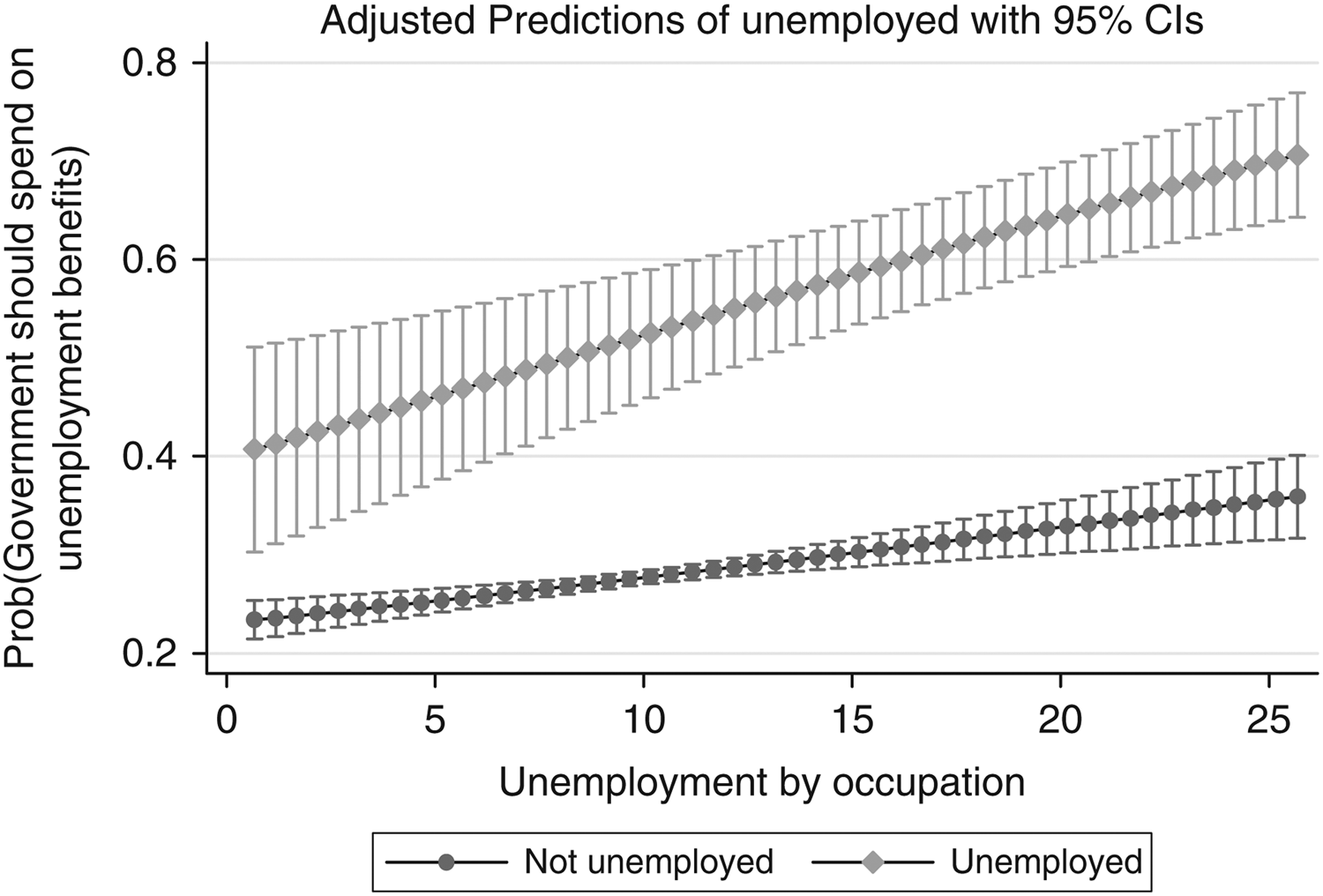

The results discussed so far confirm that both labor market status and occupational unemployment have significant independent effects. Figure 3 plots the results of a model that interacts whether the respondent is unemployed with occupational unemployment. Higher occupational unemployment is associated with stronger preferences for pro-unemployed policies among both unemployed and employed workers. But being unemployed has a strong effect regardless of occupational unemployment and the effect of occupational unemployment is stronger among those that are unemployed. Current labor market status therefore appears to be a more important driver of preferences for more government spending on unemployed benefits than the occupational risk of unemployment.

Figure 3. The effect of being unemployed on the predicted probability of supporting unemployment benefits conditional on occupational unemployment.

Last but not least, I turn my attention to the analysis of the fourth round (2008) of the European Social Survey data, which has data on whether respondents are on a temporary or permanent contract, unlike the ISSP. For reasons of space, details on the variables and full results are available in the Online Appendix. The results suggest that being unemployed and—to a lesser extent—being in a temporary contract makes it more likely that respondents think “the unemployed is government responsibility.” The alternative specification for the respondent’s partner confirms that the labor market status of a respondent’s spouse also affects their preferences: having an unemployed spouse makes it more likely to have pro-unemployed views. Being a union member, a part-time worker, and having more education have no effect. The effect of occupations themselves seem less clear cut, but being in an elementary occupation continues to have the largest positive effect on being pro-unemployed.

4. Conclusion

In this article, I have argued that the competing approaches to conceptualizing and identifying dividing lines between individuals in post-industrial labor markets entail distinct causal logic. In analyzing the effect of both labor market status and occupational unemployment, this empirical contribution can be seen as part of a broader exercise in conceptual clarification and theoretical consolidation (see also Marx and Picot, and Kemmerling, this symposium).

I find empirical support for both the occupational and labor market status approaches. An explanation of individual policy preferences that relies exclusively on occupational exposure to unemployment or differences in labor market status is therefore incomplete. Both approaches capture different forms of inequality that shape policy preferences in post-industrial labor markets. Occupational unemployment measures how the preferences of both unemployed and employed workers within an occupation are affected by the level of unemployment in that occupation. Current labor market status instead captures how the unemployed (and temporary workers) may have different preferences from the (permanently) employed across occupations.

While the discontinuous nature of labor market status is more consistent with Rueda’s initial formulation of the dualization theory (cf. Marx and Picot, this symposium), occupational unemployment represents an important additional dividing line in post-industrial labor markets. My findings further suggest that the status approach holds greater explanatory power. The unemployed exhibit significantly different policy preferences from employed workers at all occupational unemployment levels and occupational unemployment exacerbates the divergence in policy preference between outsiders and insiders.

The multiple dividing lines within the labor market that these two approaches highlight may help us make sense of the decline in class voting that has taken place in the last three decades and the electoral difficulties of social democratic parties (see introduction in this symposium). The recognition that workers’ preferences are fragmented along both occupational and contractual lines therefore has important implications for key contemporary debates in political science.

Supplementary Material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2018.42

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to two anonymous reviewers and the editors of PSRM for helpful comments. Silja Hausermann and Achim Kemmerling provided valuable feedback on previous versions of the manuscript. The author also benefited from discussions with Georg Picot and Paul Marx on this topic. Many thanks as well to the participants of the 2013 joint session of the European Consortium of Political Research (ECPR) in Mainz.