As medieval monks of Fleury knew from the vita written shortly after Abbo’s death in 1004, their former abbot had lived an eventful life, in which he had counselled kings of France, read and written widely, and spent time in England as Ramsey’s schoolmaster. This sojourn at Ramsey, though brief, had been fruitful, and the seeds of computistical learning which he had sown there would bloom in the writings of his former student, Byrhtferth.Footnote 1 However, while the great intellectual legacy of Abbo’s time at Ramsey has been widely recognized, less clear is what an eleventh-century Ramsey monk could have known about Abbo the man. At Fleury, Abbo’s murder while trying to ‘reform’ the rebellious Gascon monks of La Réole would inspire a saint’s cult to develop around him, and Aimo, his former student, to preserve his memory through the composition of a vita et miracula. But to what extent were the monks of Ramsey also involved in the process of preserving and promulgating Abbo’s (sainted) memory?

A previously unappreciated witness to Aimo’s Vita et miracula sancti Abbonis – Oxford, Bodleian Library MS Lat. Misc. c. 75 – offers new insights into Abbo’s legacy at Ramsey. This twelfth-century manuscript from Ramsey was unfortunately unknown to Robert-Henri Bautier and Gillette Labory, the most recent editors of Aimo’s Vita, but a close study of it reveals much about the textual transmission of Aimo’s Vita and the continued intellectual connections between Fleury and Ramsey. Moreover, close examination of the text itself is especially valuable, since a Ramsey interpolator has inserted additional information interesting both for Abbo’s time at Ramsey itself and for how the monks remembered it during the eleventh century. This article first introduces the manuscript and its history, before examining the textual variants in the Oxford manuscript for what they reveal about the Vita’s textual transmission, and proposing a stemma. It then analyses the Ramsey interpolations and considers the broader legacy of Abbo’s time there. Finally, it raises some possible implications of this manuscript for Abbo’s veneration.

Oxford, Bodleian Library MS Lat. Misc. c. 75 is a composite manuscript made up of seven disparate medieval components from the collection of the sixteenth-century ecclesiast and book collector, John Bale, bound together with no apparent logic save their large size of around 315 × 215 mm.Footnote 2 It is part six, fols. 144–75 of the current manuscript, which interests us. This comprises four quaternions, with two columns per page. The main text is the work of two scribes, each writing an English early gothic bookhand datable to the second half of the twelfth century. The first scribe is responsible for the first two quaternions (fols. 144–59), the other for the third and fourth (fols. 160–75).Footnote 3 This division also corresponds to a division in the texts copied. Part six of MS Lat. Misc. c. 75 contains an acephalous copy of Cassiodorus’s Historia tripartita (144r–148r); Aimo of Fleury’s Vita et miracula sancti Abbonis (BHL 3–4, 148v–159r); the Vita sancti Martialis (BHL 5552, 160r–172v); and an apocryphal letter by a Greek emperor (174v–175v), which appears to have been added later in the manuscript’s final blank folia. Based on Martial’s feast date (30 June) and the fact that the final blank folia have accrued the sort of additions common to end pages, these quaternions probably once formed part of a larger, two-volume legendary in which fols. 160–75 formed the end of the January-June volume. Fols. 144–59, containing part of the Historia tripartita and Aimo’s Vita Abbonis, presumably fell somewhere towards the end of the second volume as Abbo’s feast day falls on 13 November.Footnote 4 Since, in the catalogue of his library, John Bale describes these quires simply as ‘Haymo Floriacensis, de uita Abbonis monachi’ (Aimo of Fleury, Concerning the Life of the monk Abbo), the remainder of the manuscript was probably lost by the time he came to own it, plausibly a victim of the Reformation’s dispersal of monastic libraries.Footnote 5 A fourteenth-century inscription on 175v reveals that at that time the manuscript was owned by Ramsey Abbey; Given Abbo’s biographical connections to Ramsey and textual additions to the Vita Abbonis only found in this witness, it is highly likely that the manuscript was originally copied there.

This twelfth-century witness helps elucidate the textual transmission of Aimo of Fleury’s Vita Abbonis. Only three other complete medieval witnesses to Aimo’s Vita survive: Dijon, Bibliothèque municipale MS 1118, 91v–124v (s. ximed, copied at Fleury or its priory at Perrecy-les-Forges); Montpellier, Bibliothèque interuniversitaire, Faculté de Médecine MS 68, 56r–62v (s. xi2, copied at Saint-Bénigne de Dijon); and Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France MS lat. 12606, 141rb–146ra (s. xiiex, copied at Fleury).Footnote 6 In addition to the four complete witnesses, there also survives an extract from chapter 13 of Aimo’s Vita Abbonis in Vatican, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana Reg. lat. 1864, 73r–v (s. xi, copied in Northern France, possibly at Saint-Médard de Soissons).Footnote 7 Previous scholars have discussed this section of Vatican 1864, since it preserves Abbo’s acrostic poem Otto valens but, to the best of my knowledge, none have noted that it is not an independent witness to the poem.Footnote 8 Rather, it is an extract from Aimo’s Vita Abbonis, in which Aimo discusses Abbo’s poem, followed by the poem itself, which in some versions of the Vita is inserted into Aimo’s text. This extract is prefaced by a line turning this passage into a demonstration of the great learning of Fleury’s scholars.Footnote 9

In their 2004 edition, Robert-Henri Bautier and Gillette Labory used Dijon 1118 as the basis for their ‘best text’ edition, on account of its early date, close connection to Fleury itself and supposed lack of corrupted readings.Footnote 10 Generally, the Vita exhibits a low degree of textual variation and the majority of Bautier and Labory’s variant readings are orthographical or otherwise textually insignificant. Nonetheless, the Oxford witness is the most divergent of the witnesses and contains idiosyncrasies beyond minor textual errors. In chapter 13 of the Vita, the Oxford witness inserts the whole text of Abbo’s poem Otto valens, a variant shared only with Paris 12606 and the Vatican extract; in chapter 20 it alone inserts the text of Abbo’s epitaph, which otherwise only survives as a preface to the Vita in Dijon 1118, fol. 91; and, as discussed further below, it contains unique interpolations made at Ramsey.Footnote 11

Moreover, textual variants found in Oxford Lat. Misc. c. 75 enable us to establish its relationship to the other witnesses, to propose that the Oxford, Paris and Vatican witnesses reveal a potentially authorial revision of the Vita, and to construct a stemma. In chapter 13 of the Vita, the Vatican extract and Oxford and Paris manuscripts share a series of significant variants which reveal that they originate from a shared exemplar. Most notably, these three witnesses insert Abbo’s acrostic poem Otto valens in its entirety into Aimo’s text. However, unlike Paris 12606 and Vatican 1864, the Oxford manuscript preserves the poem’s acrostic layout and thus confirms Scott Gwara’s reconstruction of it, for which he also was unaware of the Oxford witness, and his supposition that Paris 12606’s exemplar arranged the poem as an acrostic rather than as lines of verse.Footnote 12

This insertion of the poem probably represents an authorial revision to the text.Footnote 13 In the version preserved in Dijon 1118 and Montpellier 68, Aimo describes Abbo’s poem, but states that he had not personally seen it (‘hanc epistolam ab his qui eam viderunt in hunc modum compositam fuisse didicimus’; we have learnt that this letter was composed in this manner from those who have seen it). Although Aimo includes extracts from several of Abbo’s letters in his Vita, gathering this material may have proved relatively challenging, since Abbo, unlike his contemporary Gerbert of Aurillac, appears not to have collected and curated his letters.Footnote 14 However, in the Oxford, Paris and Vatican manuscripts, Aimo’s apology has been replaced with a line stating ‘the text of that letter is likewise included in due course’ (cuius series epistole huiusmodi continetur ordine) and the poem is now included. At the same time, smaller shared changes, such as the emendation of imperfect subjunctives to present subjunctives, have been made which corroborate that the Oxford, Paris and Vatican manuscripts descend from the same exemplar.Footnote 15 Since the compilers of Paris 12606, Fleury’s twelfth-century legendary, drew upon this version of the Vita Abbonis, presumably this exemplar was an authoritative manuscript housed at Fleury.Footnote 16 The supposition must be that on later finding Abbo’s poem, Aimo revised his Vita.

Based therefore on these changes to chapter 13 and the presence of Ramsey-specific interpolations discussed below, the following stemma for the Vita Abbonis is proposed (Fig. 1):

Figure 1: The Textual Transmission of Aimo’s Vita Abbonis.

α = textual archetype; β = (authorial?) recension with Otto valens inserted; γ = Ramsey insertions; D = Dijon 1118; M = Montpellier 68; P = Paris 12606; O = Oxford Lat. Misc. c. 75 and V = Vatican 1864

Yet although the Vatican extract and the Oxford and Paris manuscripts share a common exemplar, the text of the Vita Abbonis underwent revisions between this lost Fleury manuscript and the version which was copied at twelfth-century Ramsey. At some point between its composition (datable to between 1005 and 1022) and the second half of the twelfth century, someone further revised the Vita with a Ramsey audience in mind. Oxford Lat. Misc. c. 75 is not just an English witness because it was copied in England; the text of the Vita has been ‘anglicized’ as well. Some of these changes are minor. Wording which assumes the reader is at Fleury has been modified (‘in hoc sacratissimo Floriacensi loco’ (in this most sacred place of Fleury) to ‘in sacratissimo Floriacensi loco’ (in the most sacred place of Fleury), for example, and the name of Æthelwine, Ealdorman of East Anglia and founder of Ramsey, is written ‘Æthelwinus’, rather than the French phonetic version, ‘Hehelguinum’, used by Aimo.Footnote 17 Similarly, whereas Aimo simply states that Abbo put on weight while living in foreign lands, the reviser makes explicit the implication that this was in England by inserting ‘which land is called England’ into Aimo’s text.Footnote 18

More significantly, the English reviser has also inserted textual additions relevant to Ramsey into Aimo’s text. In chapter 5 Aimo discusses Abbo’s time at Ramsey and states that Abbo ‘instructed some of the monks in the knowledge of letters’.Footnote 19 The Oxford manuscript follows this with the claim that ‘among those monks, there was one by the name Oswald, a man most learned and kind in all things’.Footnote 20 This cannot refer to St Oswald, bishop of Worcester and first abbot of Ramsey, both for chronological reasons and since he is already introduced earlier in the chapter. Rather, it likely refers to Oswald ‘the Younger’, monk and scholar of Ramsey and nephew of Bishop Oswald.Footnote 21 Ramsey’s mid-twelfth-century Liber benefactorum records that Oswald was an ephebus adolescens (youthful young man) during the abbacy of Eadnoth ‘the Younger’ (992–1006), which would accord with him receiving his preliminary education from Abbo during his 985–987 residence at Ramsey.Footnote 22 Given Oswald the Younger’s reputation at eleventh- and twelfth-century Ramsey as a scholar of great learning, it is interesting not only that he was taught by Abbo but that a Ramsey monk felt this worthy of record.Footnote 23

Equally interesting for Abbo’s time as Ramsey’s schoolmaster is an insertion made later in the work concerning Abbo’s lost Gospel commentary. Following the description in chapter 13 of Abbo’s literary compositions, the Ramsey reviser appends the following lines:

Sciendum est ergo quod ipse predictus uir de euuangeliis composuit insignem librum continentem pleniter exammusim categorias spirituales. Quem qui legerit noscere quiverit quam arduam uitam duxit. Hunc namque ut relatu multorum didicimus dictauit in Ramesyensi cenobio. Qui liber nuncupatur ABBO ut ipse.Footnote 24

This Gospel commentary by Abbo is also attested in a mid-fourteenth-century library catalogue from Ramsey, which mentions the ‘Liber Abbonis super quaedam euangelia’ (Abbo’s book upon some of the Gospels), and Michael Lapidge has speculated that the verses by Abbo which Byrhtferth tells us were inscribed in the front of Ramsey’s Bible pandect originally came from this work.Footnote 25 Unfortunately, this work by Abbo is now lost. There is no evidence that it was known at Fleury and, despite an otherwise lengthy discussion of Abbo’s compositions, Aimo appears unaware of its existence. Since the Oxford manuscript claims that this work was written while Abbo was at Ramsey, Fleury’s ignorance of Abbo’s commentary may be due to a circulation limited to Ramsey alone.

Biblical exegesis was an intellectual endeavour outside of Abbo’s usual areas of scholarly activity, namely computus and canon law.Footnote 26 Just as he wrote his only hagiographical composition, the Passio sancti Eadmundi, at the request of an English audience, so too did Abbo’s time at Ramsey compel him to embark upon the novel exercise of Biblical commentary.Footnote 27 Ramsey may have been a new foundation without an established academic pedigree, but his time as its schoolmaster compelled Abbo to broaden his intellectual portfolio. The Oxford witness’s claim that from his commentary one might know how hard a life Abbo had lived is peculiar, as Biblical commentary is rarely a format conducive to autobiographical reflection. However, since Abbo’s Quaestiones grammaticales – also written for a Ramsey audience – contains remarks on his unhappiness in England, it is possible that his Gospel commentary did similarly, especially if it were a relatively informal work compiled from his teaching notes.Footnote 28 In the years following his time at Ramsey, this work appears to have become a fundamental component of Abbo’s intellectual legacy there, as attested both by the Ramsey reviser’s interpolation of the Vita Abbonis and that the Gospel commentary had its own name, ‘Abbo’. Despite access at Ramsey to Gospel commentaries by Augustine and Jerome, Abbo’s work apparently remained influential into at least the eleventh century.Footnote 29

Although it is not possible to definitively identify when Aimo’s Vita Abbonis reached Ramsey, contextual evidence suggests this occurred relatively shortly after its composition. Abbo’s time in England localised already existing connections between English ecclesiasts and Fleury into an inter-communal Ramsey–Fleury relationship which would survive both Oswald’s death in 992 and Abbo’s in 1004.Footnote 30 The circulation of individuals, such as Oswald the Younger, and the gift of manuscripts, such as the ‘Ramsey Benedictional’ (Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France MS lat. 987), attest to the continued vibrancy of intellectual exchange between the two communities during the early eleventh century.Footnote 31 The Fleury monks also remained interested in the veneration of saints at Ramsey: the feasts of Oswald of Worcester’s death and of his translation in 1002 are recorded in the martyrology contained in Fleury’s chapterbook, while the feast of Eadnoth ‘the Younger’, bishop of Dorchester and former abbot of Ramsey (d. 1016), is entered in the margin by a later hand.Footnote 32 The transmission of Aimo’s Vita probably forms another piece of this continued connection. From the dedicatory epistle to the Vita, we know that Aimo sent a copy to Hervé, treasurer of the canons of St Martin at Tours and former student of Abbo; did the Life reach Ramsey as a gift to Byrhtferth and Oswald, Abbo’s former students there?

The Ramsey transmission of the Vita Abbonis also illuminates how the cult of Abbo’s sanctity developed in the years following his death. Although the historians Rodulfus Glaber (c. 980–c. 1046) and Ademar of Chabannes (c. 989–1034) both described Abbo’s death as a martyrdom and claimed that he worked posthumous miracles, Abbo was never widely venerated as a saint.Footnote 33 A combination of factors hindered the spread of his cult: the contentious nature of the claim that his death at La Réole was a martyrdom for monasticism; an apparent dearth, according to Aimo, of miracles; an aversion in West Francia to the cults of ‘modern’ saints; and that his feast fell on the same day as that of the already-popular St Brice.Footnote 34 This lack of popularity is seen both in liturgical calendars and the limited dissemination of Aimo’s Vita. Anselme Davril’s survey of catalogues of French liturgical manuscripts reveals that celebration of Abbo’s feast was limited to Fleury itself, though a small group of later martyrologies associated with Winchester mention Abbo’s feast.Footnote 35 Similarly, Abbo’s absence in the pre-1100 English calendars examined by Rebecca Rushforth further demonstrates that, despite Abbo’s English connections, his veneration was not widespread there either.Footnote 36 The Oxford manuscript of the Vita Abbonis thus reveals that, even if Abbo received minimal attention in Ramsey’s house history or liturgical commemoration, the monks remained interested in Abbo’s life into the twelfth century.Footnote 37

In conclusion, the witness to Aimo’s Vita et miracula s. Abbonis contained in Oxford, Bodleian Library MS Lat. Misc. c. 75 illuminates both the textual transmission of Aimo’s text itself and the intellectual world of eleventh-century Ramsey more widely. Against a backdrop of continued early-eleventh-century interaction between the Fleury and Ramsey monastic communities, the Oxford witness demonstrates that the Vita found English readers interested in Abbo’s legacy and desirous to make the text their own through the interpolation of passages concerning Abbo’s time at Ramsey. And in revealing that readers at eleventh-century Ramsey are likely to have had access to the Vita Abbonis, it raises further questions about possible Continental models which eleventh-century English authors of hagiography about recently-deceased ecclesiasts could draw upon. To those considering the nascent cults of murdered bishops, such as Eadnoth the Younger and Ælfheah of Canterbury, Aimo’s treatment of Abbo’s violent death could have provided an interesting comparison.Footnote 38

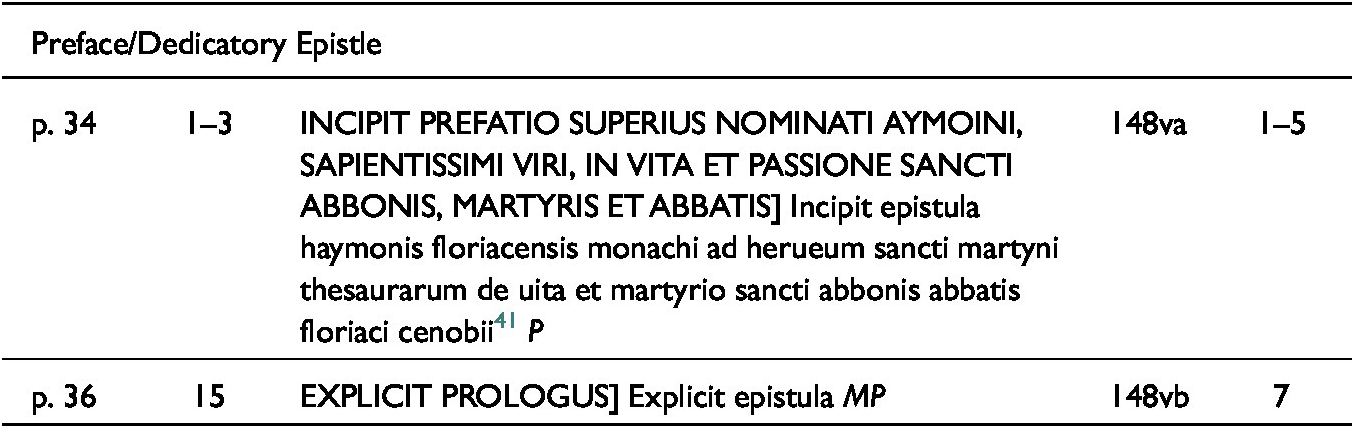

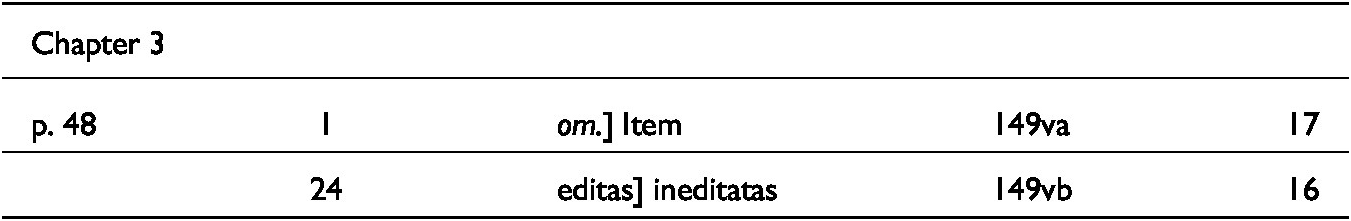

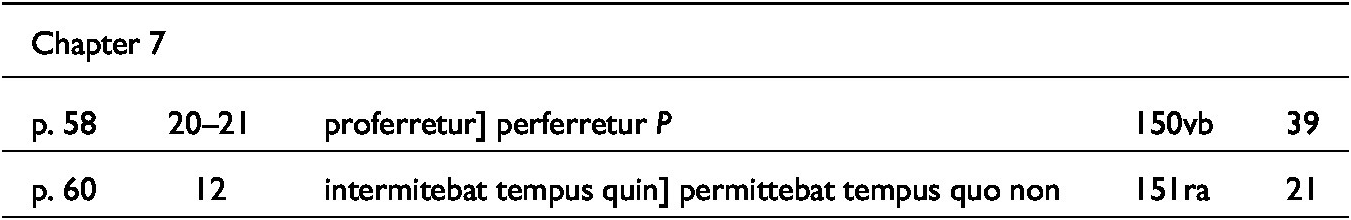

Appendix

Textual Variants in the Vita et Miracula sancti Abbonis found in Oxford, Bodleian Library MS Lat. Misc. c. 75

The text of the Vita Abbonis as found in Oxford Lat. Misc. c. 75 does not vary greatly from that printed by Bautier and Labory. However, since Bautier and Labory did not know of the Oxford witness, a supplement to their edition which marks where the two diverge will be useful for scholars interested in Ramsey and the textual transmission of Aimo’s Vita. Here the text of the Oxford witness is collated with the edition’s main text in order to provide a list of variants. Only textually significant variants are included and as a result this list does not mark common orthographic variants (e.g., ae/e, t/th, c/t) nor the variety of onomastic forms which generally accrue as a text is copied (e.g. on 152ra, Dionisii for Dyonisii, Ernulfo for Arnulfo). The Oxford manuscript has received the attention of a correcting hand; since these corrections are limited to remedying simple copying errors, they are taken as authoritative.

The text of the Oxford manuscript is primarily collated with the text of the Vita et miracula Abbonis as printed by Bautier and Labory in their 2004 edition and this edition provides the majority of the lemmata. At two points, however, the Oxford manuscript copies texts – namely Otto valens and Abbo’s epitaph – which were excluded from Bautier and Labory’s edition, but which survive in other manuscripts. For these the text of the Oxford manuscript has been collated against Gwara’s edition of Otto valens and Bautier and Labory’s edition of Abbo’s epitaph.Footnote 39

In order to facilitate comparison, when readings in the Oxford witness which differ from the printed editions are shared with other manuscripts, this is indicated through an expanded version of the sigla proposed by Bautier and Labory (Dijon 1118 = D, Montpellier 68 = M, Paris 12606 = P, Vatican 1864 = V). The insights which these shared readings offer into the manuscripts’ textual relationships are discussed more fully above, but it is worth briefly noting that some caution is required when approaching them. In creating their edition, Bautier and Labory followed a ‘best text’ approach and primarily replicated the Vita Abbonis as it is found in Dijon 1118. In doing so, they sometimes prioritized Dijon 1118’s errors over what was likely Aimo’s original text. For example, in chapter 6 they print lęctabatur; all other witnesses have letabatur, which makes far more sense and which they follow in their translation.Footnote 40 As a result, a shared set of readings between Oxford Lat. Misc. c. 75 and MP is not necessarily diagnostic of these witnesses sharing any closer exemplar than the text’s archetype.

Key to Textual Variants

Textual Variants