Persons living with HIV report experiencing disproportionately higher rates of severe and chronic pain,Reference Miaskowski, Penko, Guzman, Mattson, Bangsberg and Kushel1 as well as mood and anxiety disorders,Reference Brandt, Zvolensky, Woods, Gonzalez, Safren and O'Cleirigh2 both of which are under-identified and often untreated in HIV primary careReference O'Cleirigh, Magidson, Skeer, Mayer and Safren3 and are associated with medication non-adherence and poorer quality of life.Reference Miaskowski, Penko, Guzman, Mattson, Bangsberg and Kushel1,Reference Brandt, Zvolensky, Woods, Gonzalez, Safren and O'Cleirigh2 To date, these symptoms have only been monitored by subjective patient reports. Although these symptoms inherently involve a subjective perceptive experience, these subjective experiences might be tied to observable and quantifiable alterations in functioning.Reference Jacobson, Weingarden and Wilhelm4 The present lack of objectively assessed behaviours is highly problematic given that both pain severity and mood and anxiety disorders are associated with substance-use disorders among people living with HIV.Reference Tsao and Soto5 In particular, psychiatric comorbidity may alter pain perceptions among those with HIV and consequently fuel prescriptions of opioids, thereby putting people with HIV at an increased risk of opioid substance-use disorders. In addition to the need for objective measures of these symptoms, subjectively monitoring these symptoms requires substantial time and cost for both patients and their medical providers.Reference Insel6 Thus, sole reliance on subjective reports of pain severity, pain chronicity and mood and anxiety symptoms has many unintended, adverse consequences.

Based on these problems, there is a need to develop objective biomarkers of these symptoms to augment current self-report assessment procedures, and hopefully reduce unnecessary pharmacotherapy for pain due to inaccurate self-reports (i.e. prescriptions for opioids, among others).Reference Cunningham7 Just as importantly, objective biomarkers may facilitate timely, cost-effective solutions to monitor pain and worry severity among people living with HIV. Digital phenotyping, the use of passive sensor data (e.g. from smartwatches, smartphones) collected from daily life to make health inferences, presents a viable solution to these notable problems.Reference Insel6 No research to date has investigated the use of digital phenotyping to assess pain or anxiety symptoms in persons living with HIV. Specifically, psychomotor and sleep disturbances have previously been found to be related to pain severity and can be continuously monitored by using a wearable sensor.Reference Long, Palermo and Manees8 Thus, to address the need for continuous, low-cost and objective measures of pain and anxiety severity, we used passive actigraphy dataReference Wadley, Mitchell and Kamerman9 (measuring psychomotor and sleep patterns based on movement recordings) to predict pain chronicity, pain severity and worry severity among persons living with HIV. We hypothesised that we could accurately predict these factors by using actigraphy data alone.

Method

Participants

A total of 68 patients (70.58% female, 100% Black, Meanage = 41.28, s.d.age = 8.11, 39.71% unemployed, 19.11% working part time, 41.18% working full time, 54.41% with chronic pain) living with HIV were recruited from Charlotte Maxeke Johannesburg Academic Hospital in South Africa (for more details, see Supplementary Material available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2019.168).Reference Wadley, Mitchell and Kamerman9 All participants had HIV for at least 1 year, but participants had been living with HIV for 7.48 years on average and had been receiving antiretroviral therapy for 5.18 years on average. Regarding the HIV disease severity, 67.64% of the participants had a CD4 (cluster of differentiation 4; a glycoprotein occurring on immune cells) count below 200, suggesting that the participants were likely to experience severe and life-threatening HIV progression.Reference Post, Wood and Maartens10 Participants were not eligible for the actigraphy study if they had a physical, neurological or respiratory complaint that impeded their ability to walk, or if they had an infant less than 1 year old as each of these conditions might also alter participants' natural psychomotor and sleep patterns. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. The Human Research Ethics Committee (Medical) of the University of the Witwatersrand (clearance no: M140538) approved the following data collection.Reference Wadley, Mitchell and Kamerman9

Symptom severity

Participants completed measures of symptom severity at baseline. To measure chronic pain, participants were asked whether they experienced pain most days over the past 3 months. Those with chronic pain also reported their worst pain severity using the Brief Pain Inventory.Reference Wadley, Mitchell and Kamerman9 This instrument assesses the worst pain severity on an 11-point Likert scale from 0 (‘no pain’) to 10 (‘the worst pain you can imagine’). Worry symptom severity was assessed by asking how much participants worried about: (a) health, (b) money, (c) availability of food, (d) pain, (e) their family, and (f) fatigue on a 5-point Likert scale from ‘not at all’ to ‘nearly all the time’.Reference Wadley, Mitchell and Kamerman9 These items were summed to create a dimensional measure of worry severity. All symptom severity data was used for analysis.

Actigraphy

One week of patient actigraphy data was collected in 1 min epochs, measuring the frequency and intensity of movement during day- and night-times.Reference Wadley, Mitchell and Kamerman9 Actigraphs consist of accelerometers which record acceleration (and are designed to measure movement patterns of the individual). See Supplementary Material for more details.

Analyses

Digital biomarkers were created from the actigraphy data, using idiographic results from the Differential Time-Varying Effect Model (which measured lagged autoregressive relationships overall, as well as during day- and night-times), spectral analysis (which measured oscillation patterns overall, as well as during day- and night-times) and the distributions of the movements (i.e. mean, median, mode, skewness, kurtosis and quantiles of movement intensity overall, as well as during day- and night-times).Reference Jacobson, Weingarden and Wilhelm4,Reference Jacobson, Chow and Newman11 Psychomotor patterns are thought to reflect movements predominantly during daytime periods or patterns consistent across both day- and night-time, whereas sleep patterns were thought to be measured specifically to night-time periods. Biomarkers were not tied to the specific study protocol (i.e. not related to the study day, day of the week or day of the year), increasing the likelihood that these measurements would be more broadly generalisable. Extreme gradient boosting (a machine learning method) with an ensemble approach was used to analyse the data. Leave-one-out cross-validation was used to control for over-fitting. Primary outcomes were the correlations between predicted and observed worry and pain severity scores, and the kappa agreement between the predicted versus observed chronic pain status.

Results

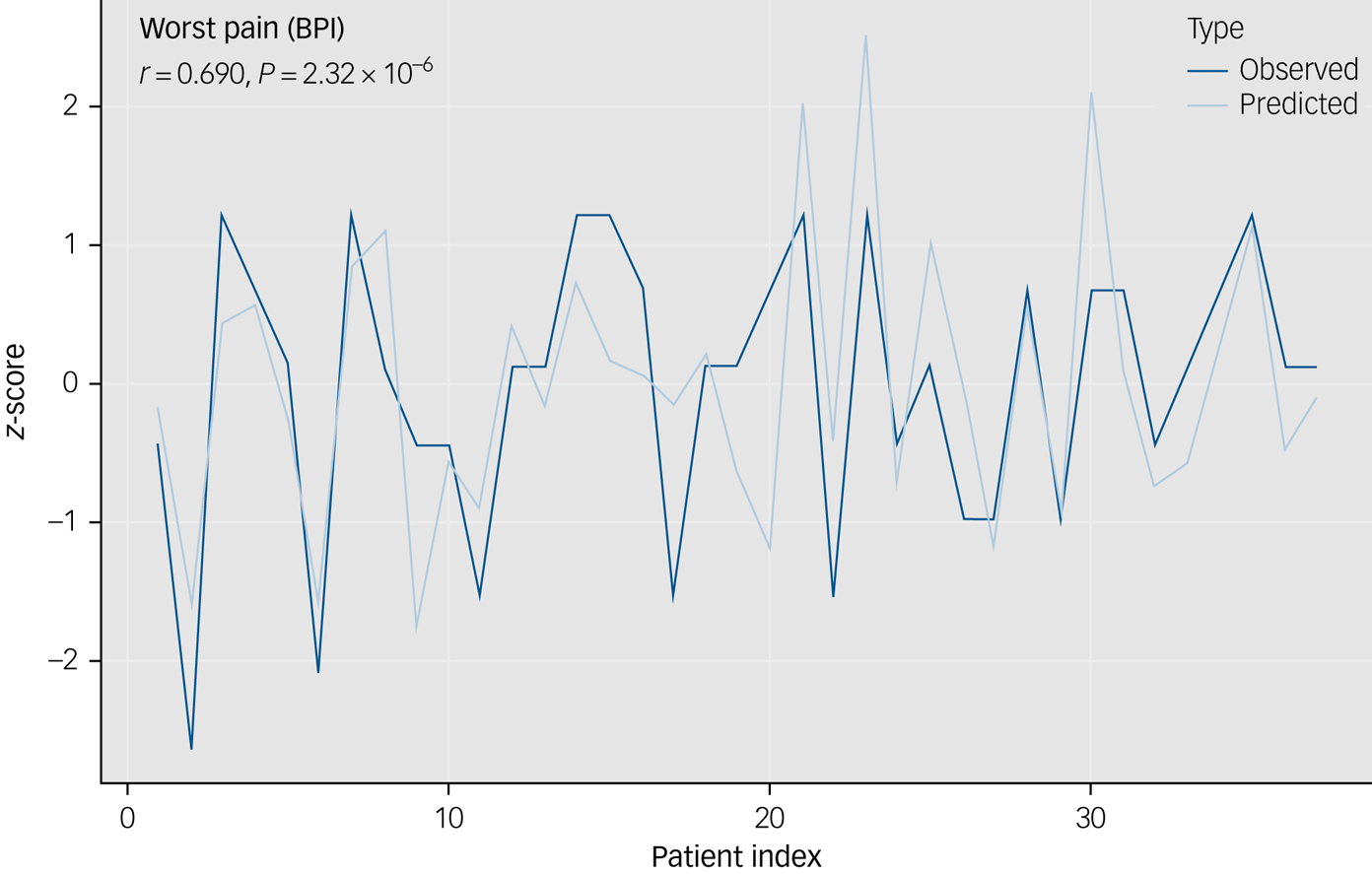

The correlation between predicted and observed values was strong for both the worst pain severity (r[35] = 0.690, 95% CI 0.472–0.828, P < 0.001) and worry symptom severity (r[65] = 0.642, 95% CI 0.476–0.764, P < 0.001) (Fig. 1). Predicted and observed pain remained strong when predicted worry severity was controlled (r[35] = 0.640, 95% CI 0.399–0.798, P < 0.001). The kappa agreement of predicted versus observed patients with chronic pain was moderate (kappa 0.485, accuracy 74.63%, P < 0.001, sensitivity 0.700, specificity 0.784).

Fig. 1 This graph depicts the observed and predicted z-scores of patients' worst pain.

Discussion

These findings demonstrate that objective passive movement data can be used to accurately detect pain symptom severity, pain chronicity and worry severity among persons living with HIV. These results suggest that objective psychomotor and sleep patterns may be used to accurately and objectively detect pain and worry severity and chronicity. These results are particularly notable given that symptom monitoring is important in delivering optimal care to this patient population. As anxiety and mood are centrally important in HIV disease management,Reference Brandt, Zvolensky, Woods, Gonzalez, Safren and O'Cleirigh2 these results may have important implications towards pain management and care in this patient population. Nevertheless, the current work has limitations: we were unable to assess symptom changes across time (given the cross-sectional nature of the self-report measures) and we do not know if changes in treatment planning may result if medical providers are provided with this information (i.e. reduce unnecessary increases in opioid dosages and ultimately limit opioid-use disorders among people with HIV).Reference Insel6 Future work should conduct randomised controlled trials to determine whether using these objective digital biomarkers could effectively direct persons living with HIV to specific psychopharmacological therapies or supportive psychotherapies instead of opioid treatments, compared with more traditional self-report methods alone (i.e. a checklist including symptoms of pain severity, depression, anxiety and substance use). Moreover, remote symptom monitoring based on objective digital biomarkers may support patient-centred outcomes by facilitating more timely intervention and allowing for more efficient use of HIV and other healthcare services in resource-limited settings.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2019.168.

Acknowledgements

The current manuscript uses public-use data made available from A. L. Wadley, D. Mitchell and P. R. Kamerman.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.