LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this article you will be able to:

• understand and explain the rationale and relevance of a person-centred and context-sensitive approach to the patient's problems

• understand and use the concept of second-order (reflective and values-sensitive) professionalism, by recognising the concept of the social contract

• point out possible implications of person-centred professionalism for specialty training.

One of the paradoxes of the current state of mental healthcare is that we have never known more about mental disorders and simultaneously been more uncertain about the science as well as the practice of psychiatry. This is remarkable. There has been a huge increase in empirical research on genetic, neurobiological, psychological and social determinants of mental disorder. Treatment protocols are mostly evidence based today and have led to better quality of care. Reform in legislation and organisation of care has led to increased patient participation at all levels of policy-making.

Yet, despite these improvements there is much unease about psychiatry, both as a science and as a practice. There is no consensus on what mental disorders ‘are’. Most determinants of mental illness lack specificity. There are differing views on where psychiatry should be heading: towards increased biomedical reductionism and a reunion with neurology (Insel Reference Insel and Wang2010), towards a branch of complexity science and/or network theory (Friston Reference Friston, Redish and Gordon2017; Borsboom Reference Borsboom, Cramer and Kalis2019) or towards a primarily practical, context-sensitive and recovery-oriented discipline that enables clinicians to adopt a flexible, values-based stance with respect to their role (Slade Reference Slade2009; Bhugra Reference Bhugra, Tasman and Pathare2017; van Os Reference van Os, Guloksuz and Vijn2019).

How should psychiatrists deal with the uncertainties of their profession and the ambiguities of their role? How are they going to shape the interactions with their patients? If negotiation of values is at the heart of the profession as Woodbridge & Fulford (Reference Woodbridge and Fulford2004) claim, how are clinicians taught to practise this? How could psychiatrists argue for the legitimacy of their profession?

This article argues for a second-order, ‘wise’ professionalism that enables clinicians to better address the daily needs of their patients and provides them with a vocabulary that helps them negotiate about the values-laden dimensions of their role in different contexts. There exists a bewildering number of new approaches to professionalism in psychiatry. This article does not offer yet another model, but sketches a way of thinking that helps clinicians to ‘design’ and legitimise their interactions with patients and the healthcare system. This way of thinking starts at grass-roots level, bottom-up, within practice. So, let us start.

Symptoms: their interactions and relations

Signs and complaints of a psychiatric disorder develop within a web of relations. The (fictitious) case vignette in Box 1 gives an impression.

BOX 1 Case vignette: Peter

Peter is a 24-year-old history student. For the past couple of months, he has suffered from depressive complaints. Peter enters the consulting room and begins to describe what he experiences: lack of concentration, apathy, sleeping problems, anhedonia and negative ideations. He is finding it difficult to finish his studies. He is almost a year behind and feels bad about the lack of progress. His psychiatrist listens to what he says. She pays attention to his physical appearance, his psychomotor behaviour and the tone of his voice. She asks some questions, aiming at clarification and more precision. She checks whether Peter's condition fulfils the criteria of a psychiatric disorder (major depressive disorder, especially). While doing so, she gets a feeling for the contact between Peter and herself. She asks about Peter's interpretation of what is going on and what friends and relatives say about the situation. In doing so, she shows her interest and her eagerness to know Peter better. She weighs the opinions of others against her own professional impressions. Thus, she develops an image of Peter as a person and about the role of depression in the story of his life. She also begins to know what is going on at a deeper level. She notices a mixture of transferential reactions in Peter: his dependence, his signs of distrust in her and a tendency to devalue her attempts to understand him. She begins to feel an inclination to prove her competence and commitment.

(Adapted from Glas Reference Glas2019a, p. 23)The psychiatrist listens and observes. She applies scientific knowledge by asking specific questions. She uses common-sense understanding to assess the impact of Peter's condition on his relationships and self-image. She implements communicative skills by probing for underlying patterns that signify what kind of person Peter is. She displays organisational talent by working within a limited time span. She strikes a balance between what Peter himself needs to tell her and what she needs to know from a professional point of view.

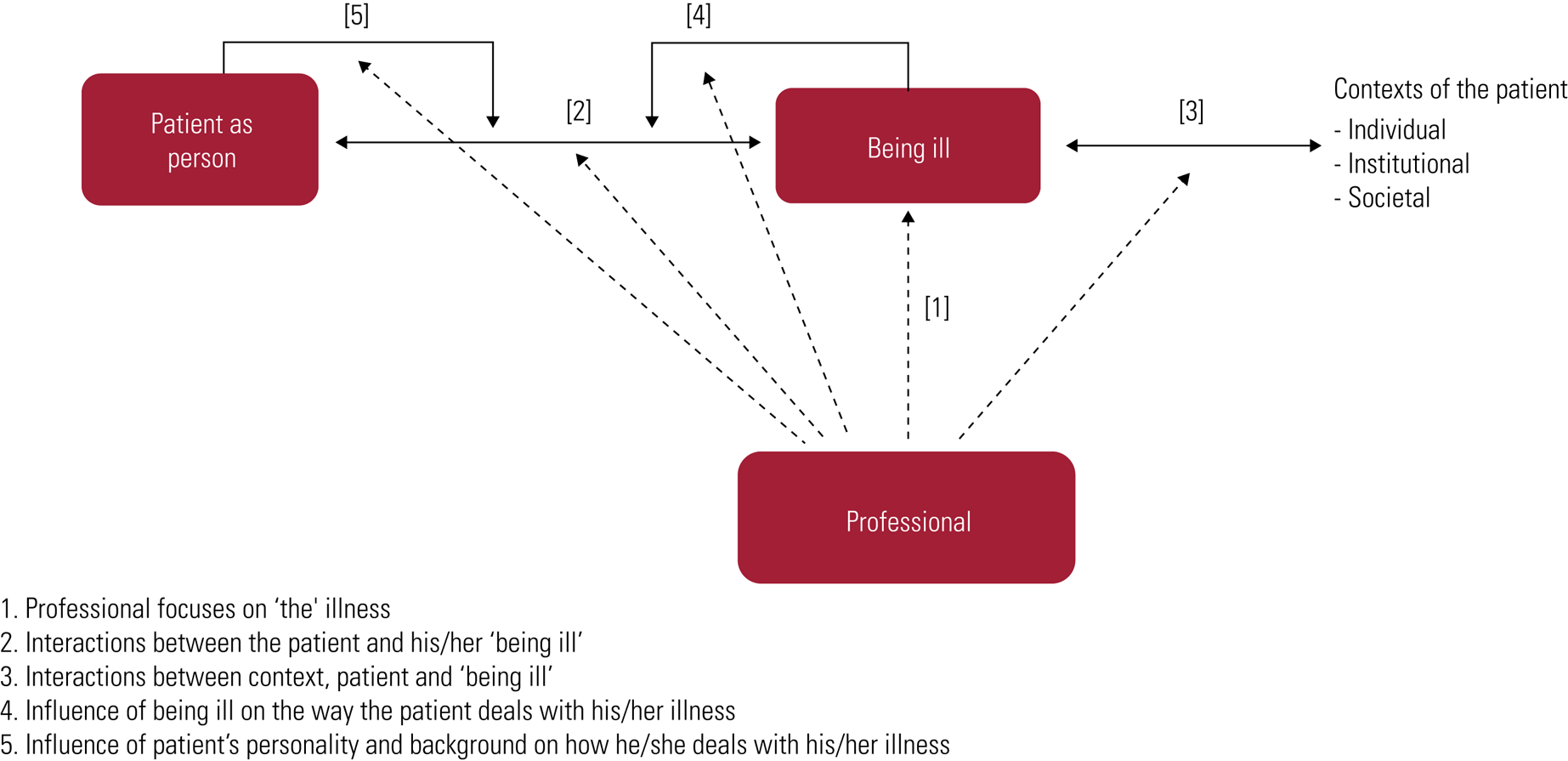

Figure 1 tries to capture the web of relations in which the doctor–patient interaction evolves. Peter talks about his complaints, the psychiatrist focuses on signs and symptoms (relation [1]). By narrating what is going on, by showing how he feels about it, Peter relates to his illness [2]. The psychiatrist investigates the impact of what relatives and friends say about Peter's condition [3]. She is curious to find out whether the delay in Peter's study has financial or other consequences [3]. She gets an impression of how Peter's illness affects how he relates to that illness. Peter's feelings of helplessness and powerlessness have a significant impact on how he deals with his complaints [4]. She also pays attention to the influence of person-related factors on how Peter relates to the illness (influence of [5] on [2]). Such person-related factors are, for instance, personality traits, biographically determined preoccupations and personal values. Peter's initial transferential tendencies [5] and the subtle countertransferential reactions of the psychiatrist contain important messages about the kind of person-related factors that should be considered in order to acquire a proper view on how to conduct the treatment process.

FIG 1 The professional pays attention to interactions between patient, illness and context.

This diagram of interactions and relations shifts the clinician's focus to person-bound (self-relational) and contextual aspects of the patient's condition (Miles Reference Miles and Mezzich2011a). The boxes in Fig. 1 (the illness, the patient as person, the professional role) do not exist by themselves, but should be viewed as shaped and determined by interactions. To illustrate the relevance of this broader perspective, we focus again on Peter. One of his most pressing complaints is his demoralisation. The diagram helps to understand that this demoralisation may signify at least three different things. Demoralisation can be seen as a symptom of depression [1]; it can be interpreted as resulting from the influence of the depression on how Peter relates to his illness [2]; and it can be considered as a latent character trait that has become manifest due to the depression [5]. There are, moreover, combinations of these three kinds of demoralisation.

To add to the complexity, psychopathological phenomena such as demoralisation are often layered. This layeredness may be seen as a result of long-lasting, self-amplifying and/or looping interactions and relations. Peter's self-image, for instance, is negative because of the depression [1] [2] [4] and this affects his interactions with peers [3], who, as a result, may react by distancing themselves or adopting a parental attitude [3], which, in turn, may reinforce Peter's feelings of inferiority and insufficiency and exacerbate his demoralisation [5]. This will also negatively affect his willingness to be treated [2].

The psychiatrist's interpretation is another influential contextual factor [3] with sometimes uncertain consequences. Establishing a diagnosis such as depression and pointing out how demoralisation fits in the picture may lead to recognition and relief, but also to increased negative self-evaluation and (self-)stigmatisation.

A more radical implication of this complexity is that symptoms should be seen as products of interactions instead of as immediate expressions of underlying psychopathology. Symptoms are often layered and, especially in chronic illness, the product of interactions between oneself (as patient), one's self-image, one's perception of others, including the clinician, the factual behaviour of others and the impact of all these factors on how one deals with the illness. What psychiatrists see is not merely the expression of an underlying disorder, but the result of these often self-amplifying and/or looping interactions and their internalisation by the patient (Hacking Reference Hacking, Sperber, Premack and Premack1995; de Haan Reference de Haan2020; Double Reference Double2021).

The clinician in the web of interactions and relations

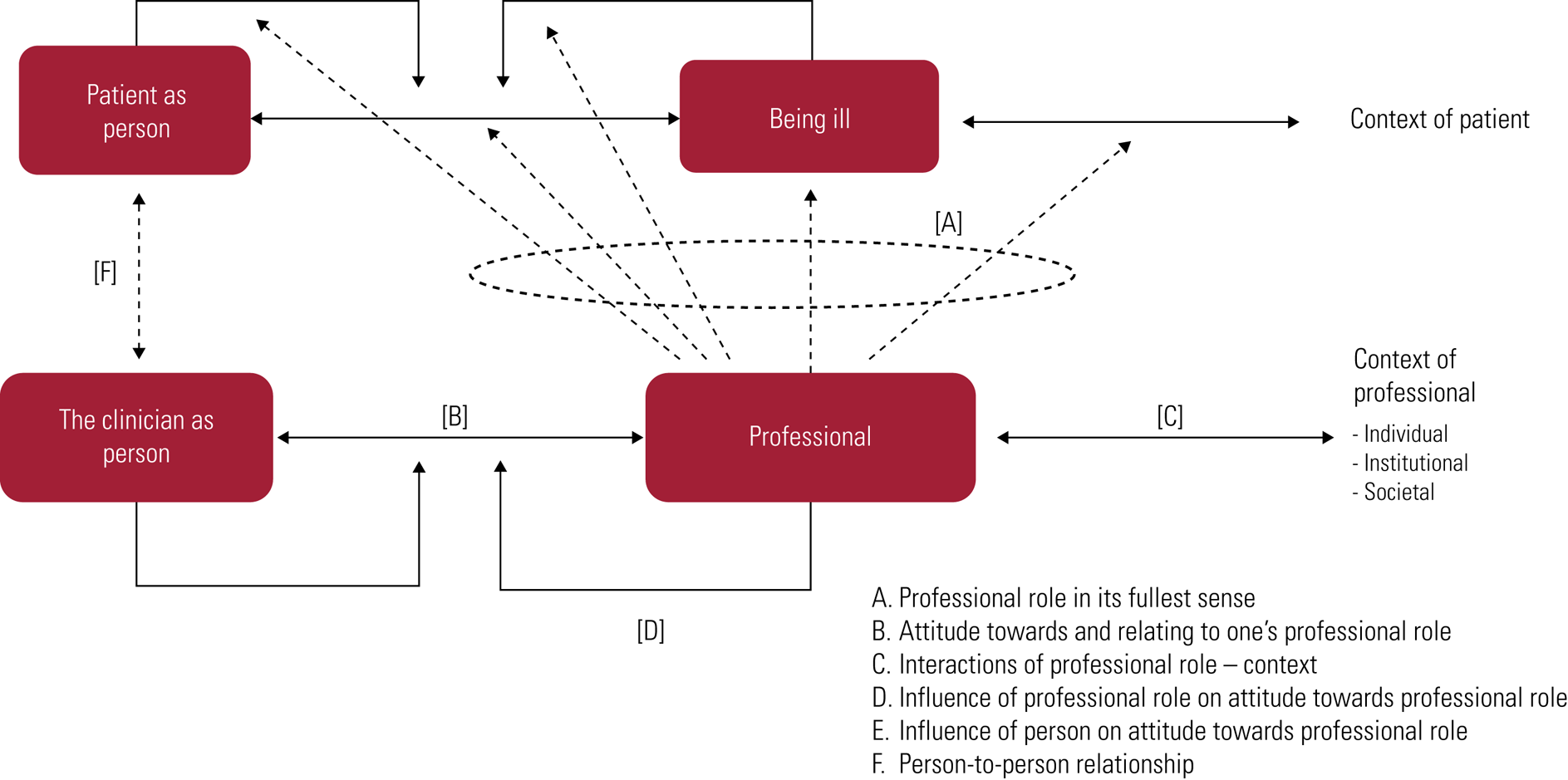

The clinician is also part of a web of relations and interactions. The main message of Fig. 2 is that clinicians do not coincide with their expert role (relation [A]) and need to see themselves as co-designers of the many interactions in which they are involved [B]–[F]. Since these interactions are values-laden, clinicians need to appropriate the vocabulary that is needed to address these values-laden dimensions.

FIG 2 In their professional role, the clinician relates in different ways to that role.

Figure 2 indicates that professionals are persons who relate to their role [B]; and by doing so, interact with and function within a multilayered context [C]. By interacting with the patient (micro-level) they also interact with the administrative, legal and financial aspects of the healthcare system (meso-level). Clinicians are also increasingly asked to respond to the many societal expectations of their role. They must account for what they do and respond to the demands of public health agencies and authorities that are responsible for certification and quality control (macro-level). All these contexts influence one another [C].

One's self-relating as a clinician is influenced by one's professional development. Ideally this self-relating amounts to an identity that is skilful, stable, personal, context-sensitive and open to what is new in the field [D]. Part of one's training as a specialty trainee (resident) is to grow in one's role as a future psychiatrist and to experience that this role fits. This is (and remains) a dynamic process in one's professional development. Contexts may change and may make clinicians feel ill-suited for roles they once performed effortlessly. Person-related factors such as personality traits and biographically determined biases, sensitivities and preoccupations help shape one's identity as a clinician [E]. They become manifest in one's countertransferential reactions. Moral sensitivity and the capacity to reflect on one's own biases and inclinations belong to the core competencies for ethically appropriate role fulfilment. Finally, there is also, usually mostly implicitly, the reality of two persons sitting in a room, with their personal histories, biases, vulnerabilities and convictions [F]. There may be rare moments in which it is appropriate in the interaction with the patient to point out not only what kind of professional one wants to be, but also why and how this fits with who one is as person, with one's world-view and/or core concerns. The above suffices, I guess, to state that professionals are more than a bundle of competencies and skills and do not coincide with their expert role (Radden Reference Radden and Sadler2010; Glas Reference Glas, Peteet, Lynn Dell and Fung2018).

The social contract as basis for professional practices

Apart from being experts, professionals are also bound by what is called the social contract (for an introduction see: Freidson Reference Freidson2001; Sciulli Reference Sciulli2005; Hafferty Reference Hafferty2006; Bloom Reference Bloom, Standing and Lloyd2008; Bhugra Reference Bhugra and Malik2011). The term sounds somewhat abstract but refers to something concrete, i.e. the interactions and negotiations at meso- and macro-level between professional organisations, governmental agencies, insurance companies, administrative bodies, representatives of the judiciary and public administration, and patient representatives. All these interactions and negotiations aim at the provision of good healthcare and have as outcome ‘the’ social contract. The contract defines the conditions and criteria for adequate care given the impact of psychiatric problems on patients’ lives and society. Conditions are usually aiming at some form of control: financial, legal, institutional, societal and in terms of security. The criteria involve standards for good clinical practice. The contract entails a transaction. By embracing appropriate attitudes and behaviours and by proving to be committed to integrity, accountability, altruism and the public good, doctors are granted to receive something in return: a salary and the privilege of defining criteria for adequate role fulfilment and for entry to the profession. The contract establishes and confirms in other words that professionals are worthy of the public's trust because they are working for the patients’ and the public's good (Swick Reference Swick2000; ABIM Foundation 2002).

The concept of social contract is important because it defines the jurisdictions under which professionals perform their duties. There is a public debate about the boundaries and legitimacy of the psychiatrist's role and this debate is settled on grounds that are defined by the social contract. The notion of social contract illustrates, moreover, that values and norms are inherent to professional practice and even belong to the very core of professionalism. The negotiations about the psychiatrist's role are ultimately negotiations about values, i.e. about what different stakeholders deem to be important and desirable with respect to the psychiatrist's role in dealing with people with a mental illness.

What is stated here may sound like a rational, deliberate and tranquil exchange of views leading to policies based on a democratic process of decision-making. Reality is much messier, of course. Who is responsible for what? Difficult questions may arise here. Should all troublesome and difficult behaviour of citizens be put on the table of mental healthcare providers? Who is responsible for the mental health consequences of individualism, urbanisation, social inequality and stigma? And who should warn against the negative influences of living in a culture in which privacy is threatened, information can no longer be trusted and so much importance is attached to status, working performance and physical appearance? Our conceptual framework suggests that professionals should show responsibility by informing policy makers and the public about the social and societal factors that predispose to psychopathology. Professionals may give relevant and important suggestions about how to mitigate these factors; and if they cannot be mitigated, how to deal with them in order to prevent mental health problems from becoming unmanageable.

Renegotiating the social contract as part of reflective and values-sensitive professionalism

Let us focus now on a fictitious case vignette (Box 2) that illustrates how changes in the social contract shape the psychiatrist's role and may affect the psychiatrist's core values. John's situation is not rare nor is his response. For many years John's professionalism coincided with what he and others considered to be his expert role. This coincidence lasted so long that it shaped John's professional identity. The financial, administrative, and societal contexts have changed, however, and now John's role does not fit any longer. The result is a mismatch between what the healthcare system expects from John and what he sees as his identity and proper role. John does not find a way to preserve and use his expert knowledge and skills and, at the same time, creatively and flexibly transform his role into something that meets the current requirements. This is not an easy job, of course; and none of us would probably be able to do this alone. What one misses in his reactions, however, is the awareness that clinicians do not coincide with their expert role (Fig. 2, relation [A]) and need to see themselves as co-designers of the many interactions in which they are involved [B]–[F]. The social contract on which his role is based has considerably changed, but John fails to recognise this. He and his colleagues do not define themselves as a group that co-designs the interactions at the meso- and macro-levels of organisation of healthcare. The result is a response that is passive and resistant. John recognises his negativism but has no tools to change it. He lacks the knowledge and skills to address meso- and macro-level processes in healthcare; and feels, as a result, powerless about the many transformations in the delivery of care in his facility.

BOX 2 Case vignette: John

John is a 59-year-old psychiatrist in an addictions clinic. He is head of two units and loves his work. He is creative and unconventional and can turn almost every crisis into something positive. His success as a clinician has made him a respected and highly valued member of the medical staff. Recently the situation has changed. Financial constraints, changes in the composition of the team and huge administrative requirements have made professional life almost impossible. His appointment has been reduced, both in the number of hours and in the kinds of activities he is allowed to do. He used to do almost everything: diagnostic work, psychoeducation, group psychotherapy, family therapy, pharmacological treatment and so on. Now, triage has become one of his main duties as well as lobbying for the transfer of his patients to other units and out-patient settings. Consultations with insurance companies and managers in the hospital take lots of time and effort. Too little is left of what made his professional life so valuable and interesting. He loved to motivate patients, to help them change their lifestyle and face the underlying problems. But now, his job has become administrative to a large extent. ‘Does it make sense at all, that I am here, in this clinic, doing all this work, instead of understanding and motivating patients?’, he asks. He notices that he has become cynical about his job and about his role. He has complained about the changed conditions in the medical staff, but they said they couldn't do very much about it. John recognises his own passivity and negativism but does not see how to transform his own crisis into something positive.

This analysis does not imply, of course, that each clinician should see themselves as a negotiator with representatives of insurance companies or the public administration. What is needed is awareness of the intrinsic relevance of the contextual changes just mentioned and a vocabulary that helps to identify and discuss the concerns, values, interests and virtues that are at stake in the negotiations at meso- and macro-levels. The voice of the profession is (via representation) of crucial importance in these negotiations. Doctors are, after all, health advocates. Their values aim at what matters to patients.

The above illustrates that John's problem is not only individual and existential, but also societal and an expression of tensions in the system. There is, indeed, an existential problem because of the changes in his role, but this is half of the story. The other half is about John's ability to relate to changing conditions at a meso- and macro-level of interaction. John defines his problem in terms of authenticity. He considers the contextual changes as a threat to his authenticity. Authenticity is a virtue that comes to expression in the ability to remain faithful to one's core values. But this faithfulness does not imply resistance to any kind of change. It is compatible with adaptation, if the process of adaptation is carried out in a genuine and values-sensitive way that stays close to one's core values and concerns. Sensitivity to values presupposes the ability and willingness to amplify one's reflective space. This is done by taking notice of the meso- and macro-level dimensions of professionalism. John could, for instance, raise his voice in his own professional organisation; discuss his worries with the administrators of the hospital; search for common ground between him, the administrators and patient representatives; take part in the council of hospital employees; participate in advocacy groups; raise public awareness of what is going on in the sector, for instance on social media; or become politically active. Professionalism entails the awareness of and the ability to negotiate about the conditions under which healthcare is delivered. This means that, occasionally, professionals must redefine and reinvent their identity. This is difficult, of course. But it is not impossible if all stakeholders keep aiming at the preservation of the common good: good care for the mentally ill and sufficient protection of the public sphere.

Implications for psychiatric education

Norms, preferences, interests and values play an important role in the formation of professional identity. They are transmitted via specialty training programmes, role models, the culture of mental health institutions, and by the expectations of patients, their families, other stakeholders and society.

Values also determine one's responses to the institutional dynamics within mental healthcare and to the societal role of psychiatry. They are therefore relevant not only at the level of practical decision-making but also in broader contexts. They are also present in implicit working models in the minds of clinicians (and patients), for example in the ideas they have about the nature of mental disorder and the proper role of the psychiatrist.

Much of what has been said so far corresponds with the principles of values-based practice (VBP) (Fulford Reference Fulford and Radden2004; Dudas Reference Dudas2021). Here, I want to draw a complementary picture of what a values-sensitive approach means for psychiatric education (Boxes 3 and 4 for more background).

BOX 3 A broader conceptual framework: the normative practice approach

The story told here is part of a larger one (known as the ‘normative practice approach’; see Glas Reference Glas2019b), which has the ambition of explicating the intrinsic norm-responsiveness of the web of relations in which healthcare professionals do their job. The idea is that healthcare should be viewed as a practice that responds to a variety of norms or principles, i.e. qualifying norms (norms that define the nature and purpose of the practice), foundational norms (principles and insights on which the practice is based; usually, scientific and technological expertise, insight into design, engineering and the like) and, finally, conditioning norms (norms or principles that refer to the legal, administrative, institutional and economic conditions that enable practitioners to fulfil their role).

BOX 4 A broader conceptual framework: the intersection of clinical and scientific knowing

One other element of the larger story is epistemic and suggests a view on the relationship between science and clinical knowing. The relationship between these two can be understood as determined by a difference in epistemic stance (see also Montgomery Reference Montgomery2005; Miles Reference Miles and McLoughlin2011b). Scientists aim at an understanding of underlying patterns and mechanisms, and focus on what holds in general. Clinicians are interested in particulars, the illness of the individual patient at a particular point in time.

The difference in epistemic stance is paralleled by a difference in contexts. Scientists develop their insights by fixing and standardising the experimental conditions. Clinicians try to understand by focusing on contextual detail and development in time.

Theories can be seen as cognitive artefacts that help organise one's knowledge in a particular field of science. Clinical expertise consists in the ability to make use of these artefacts, or prototypical derivatives of them, by intuiting their relevance in a wide variety of contexts. This intuiting entails the ability to assess the relevance of a particular piece of knowledge (the cognitive artefact) in a particular context (Miles Reference Miles and McLoughlin2011b). This context is shaped by the web of relations that we discuss in the text. This assessment is, in a way, also norm-responsive: it is an ability to assess relevance and to attribute meaning – given a certain body of theoretical knowledge – to a situation (the illness) that can be seen as a node in a web of norm-responsive relations. The success of the intuiting corresponds, in other words, to the adequacy of the interpretation of what matters in that situation, understood as a nodal point in a web of norm-responsive relations. Phrased differently: the translation of scientific findings into clinical practice can be seen as involving a change of stance that is enabled by the capacity to make abstract knowledge relevant (and concrete) in new contexts, understood as webs of relations. This translational capacity is still little understood, except for the role of statistics in decision-making. In values-based practice, there exists a tendency to separate science and values-based clinical practice and view them as more or less isolated, albeit complementary pillars. In my view there is more overlap and interaction.

I see three concrete applications (summarised in Box 5).

BOX 5 Recommendations for specialty training

• Give first-year specialty trainees a grass-roots level introduction to the philosophy of psychiatry by teaching them to recognise implicit models of mental disorder in the interaction with patients and by practising values-sensitive communication about these working models and their implications.

• Offer third- and fourth-year specialty trainees learning experiences in the broader (meso- and macro-) contexts of mental healthcare; teach them to recognise and address the perspectives of other stakeholders.

• Acquire second-order professionalism: invite specialty trainees to reflect on, deal with and actively design their role given the broader contexts in which they practise (Fig. 2, relation [C]) and their own history with the professional role ([B], [D], [E]).

First, in the early years of specialty training, I recommended that a couple of hours are devoted to teaching and discussion about the concept of mental disorder. Figure 1 could be used to explain that illnesses are not things in themselves and that symptoms are not just expressions of underlying dysfunctions but also often a result of personal and contextual reactions to the initial manifestations. Some well-known models of mental disorder can be better understood with the help of the diagram. I refer to Box 6 for an explanation of how this could work. The idea is not to give a philosophical and theoretical exposé, but to let specialty trainees themselves experience and detect how they communicate about what is going on in the patient and, especially, about the diagnosis. How do they explain what the patient experiences? Which model of disease are they implicitly or explicitly applying? And are they aware of the implicit disease model held by the patient? Is there a tension between these models? How do they communicate and adapt their role when there exist contradictory views on the nature of the patient's mental illness? The focus of this module is on Fig. 1 and the balance between the different relations/interactions.

BOX 6 Introduction to concepts of disease

Classical biomedical approaches see disorders as real entities out there in the world, i.e. as things with an existence in themselves located in the brain (Boorse Reference Boorse1975). This view decontextualises psychiatric illness and sees it as an external condition that should be separated from coping and other psychological processes (Fig. 1, relations [2]–[5]).

According to another dominant view (constructivism; Hacking Reference Hacking, Sperber, Premack and Premack1995) mental illnesses are relational and a social construction, i.e. a product of social circumstances (absolutisation of relation [3]); this view denies the relative autonomy of certain disease processes [1].

The pragmatic (or practical kind; Zachar Reference Zachar2015) approach views illness categories and classifications as practical tools that help organise one's work, given the purposes of that work.

There is no deeper meaning in the concepts clinicians use and they may use whatever concepts they need to reach their goal: improving the lives of patients [2], alleviating the burden of it for others [3] and the patient [4], [5]. There is also an ideological view that denies that mental illnesses exist [1] (Szasz Reference Szasz1961). The very concept of mental disorder is based on a category mistake (the application of the wrong concept to certain behavioural phenomena. According to this view, all relations in Fig. 1 are based on misconception and lead to oppression of deviant persons by the medical establishment. For a concise overview see Kendler et al (Reference Kendler, Zachar and Craver2011).

The second application consists in a series of learning experiences in other, broader contexts than the consulting room. The idea behind this proposal is that the ability to adequately address stakeholders in these broader (meso-)contexts has become a significant part of the psychiatrist's job (Wynia Reference Wynia, Latham and Kao1999; ABIM Foundation 2002; Mitchell Reference Mitchell and Ream2015). Current curricula tend to offer insufficient input for the acquisition of skills and attitudes that are relevant in these broader contexts. Several of these contexts are relevant and potentially instructive. One of the easiest activities to organise could be to give consultations and/or teach about mental problems and mental healthcare in non-medical settings. These activities could be employed in schools (both primary and secondary schools); on social media; in science cafés; by interacting with patient or advocacy groups; or by interacting with other non-governmental organisations that aim at the welfare of psychiatrically disabled persons. Another example is to organise internships in which the specialty trainee is allowed to accompany members of the board of the clinic or the head of finances and/or administration to meetings with other parties, such as representatives of insurance companies, certification agencies and public administrators. Specialty trainees could accompany medical directors in their consultations with the head of the local police, the mayor and other administrators with a responsibility for public safety. They could be asked to report and reflect on their experiences and to summarise what they learned from the interactions and communications. Figures 1 and 2 could be used to structure these reports. The focus is on one's actions and interactions in the wider (meso- and macro-) context of current mental healthcare.

Third, more emphasis could be put on the competence of professionalism. Here Fig. 2 could be used as a heuristic framework to guide one's reflections. Professionalism is, as we have seen, more than the ability to perform the (medical) expert role [A]. It also involves the second-order competence of being able to reflect on, deal with and shape one's role depending on the wider context [C], one's own history with the professional role [B], [D] (Birden Reference Birden, Glass and Wilson2014) and one's personality and existential stance [E]. Personal psychotherapy remains, of course, an important route towards the achievement of a reflective stance. Other contexts for the acquisition of the skills just mentioned are individual supervision and coaching, group supervision and mentorship; role switching (chairing a session; learning to interact with superiors and non-medical members of the organisation); and collaboration with other parties outside the facility, such as patient organisations, advocacy groups, experts by experience, people that are present in the social media, and so on.

Conclusions

The article offers a philosophically informed perspective on person-centred psychiatry by viewing it as an attempt to do justice to the person- and context-bound aspects of psychiatric illness. It describes the role of the psychiatrist as (co-)regulator of relationships, not only the relationship with the patient but also with stakeholders in meso- and macro-contexts of healthcare. It pleads for inclusion of philosophical reflection in psychiatric education and for internships at the intersection between healthcare and the social domain during specialty training. It shows how this amounts to a second-order, reflective, values-sensitive and ‘wise’ professionalism. The critical point in this second-order competency is recognition of the inherent normativity of the relations in which the professional role is embedded. This normativity is made explicit, at least partially, by the social contract that defines the jurisdictions and boundaries of the profession.

Psychiatrists currently often lack the skills and the vocabulary to operate in this often highly polarised and politically laden arena. They should learn to do so, however. Based on a clear view on the nature and boundaries of their practice they should acquire the sensitivity and skills that are needed to negotiate the terms of the social contract with relevant stakeholders. The conceptual and values-oriented framework sketched here may help clinicians to focus on what is essential and to responsibly design and legitimise their interactions with patients and the healthcare system.

Funding

This work received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of interest

None.

An ICMJE form is in the supplementary material, available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bja.2021.75.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

1 Person-centred care:

a puts the patient's values above the clinician's values

b focuses on treatment and care and not so much on diagnosis

c denies the existence of mental disorder

d solves the weaknesses of the biopsychosocial model of George Engel

e is Hippocratic in that it focuses on the person in the illness instead of on the illness in the person.

2 In Fig. 1, arrow [4] (the impact of the illness on how patients deal with that illness) indicates that:

a illnesses are sometimes self-enhancing

b illnesses are sometimes consciously self-imposed

c illnesses are sometimes just an expression of one's personality

d illnesses are sometimes a product of one's imagination

e illnesses are sometimes a product of the context.

3 Clinicians relate to their professional role, which means that they should:

a always try to limit the influence of their personality on how they fulfil their role

b always make their personal biases with respect to their role explicit to each patient

c try to adapt and change their personality to the professional role they are supposed to fulfil

d learn to reflect on and selectively use the influence of their biographies and personal values on how they shape their role

e try to become as non-transparent and equanimous as possible, given the risk of boundary transgressions.

4 Teaching person-centred care in specialty training involves all the following activities, except:

a following an introductory course on models of disease

b learning to adopt the role of health advocate in non-medical settings

c telling every patient about one's own personal involvement with the professional role

d reflecting on one's personal history with the professional role

e making values-sensitive aspects of one's treatment proposals explicit to patients and colleagues.

5 Medical professionalism is based on a social contract, but that contract does not include criteria and regulations with respect to:

a the economic conditions for psychiatric practice

b the legal conditions for psychiatric practice

c the institutional conditions for psychiatric practice

d the establishment of a psychiatric diagnosis

e the social conditions for psychiatric practice.

MCQ answers

1 e 2 a 3 d 4 c 5 d

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.