Impact statement

Marine plastic pollution has evolved into another global environmental crisis that affects the health of people and the oceans. This evolution matches global political economic regimes as they shift from increasingly permissive and less protective of ecological systems and societal needs. As the member states of the United Nations prepare for a new treaty to end plastic pollution, it is important to ask what an effective agreement would look like. To do this, the foundational work of Karl Polanyi and versions of stage theory are reviewed. Polanyi argued that if markets are seen separate from society and are not restrained to protect nature and people, self-regulated markets would destroy society and nature across stages of less and less protective historical periods. Thus an effective agreement to reduce plastic pollution, all plastic production and use must be restrained – directed by the needs of people and nature.

Introduction

The United Nations Environment Assembly decided in March 2022 to create a new binding treaty to deal with plastic pollution. What would an effective policy look like? To answer this question, this paper places marine plastic pollution (MPP) in structural context to explain the social forces behind what is increasingly called the “plasticene” (Reed, Reference Reed2015; Tiller et al., Reference Tiller, Arenas, Galdies, Leitão, Malej, Romera, Solidoro, Stojanov, Turk and Guerra2019; Rangel-Buitrago et al., Reference Rangel-Buitrago, Neal and Williams2022).

Specifically, I rely on stage theory and the work of Karl Polanyi. Stage theory characterizes shifting expressions of economies such as the post-World War II (WWWII) “Fordist” economy and the following “neoliberal” period explained below. In 1944, Polanyi (Reference Polanyi2001) published one of the more important contributions to political economy of the 20th century, The Great Transformation, which provides important insight relevant to MPP.

The paper demonstrates that the answer to MPP problem depends on how the global plastic flow is embedded in socioecological protections. This is because 3–4% of plastic that leaks from annual global plastic production (Jambeck et al., Reference Jambeck, Geyer, Wilcox, Siegler, Perryman, Andrady, Narayan and Law2015) is dialectically constitutive with post-War stages of capitalism itself, that is, plastic and capitalism organize each other. Plastic flow is expected to “triple globally from 460 Mt in 2019 to 1,231 Mt in 2060” (OECD, 2022, p. 21). As capitalism and embeddedness change in stages so too does MPP and the appropriation of “cheap” ocean work (see Moore, Reference Moore2015) and unequal ecological exchange in a galloping treadmill of production (ToP).

Plastics in the global economy

Plastic was first made in 1907 but was “insignificant from a historical perspective” until WWII (Geyer, Reference Geyer2020a, p. 33). Since then, plastic is increasingly an essential “workhorse material” (Hahladakis, Reference Hahladakis2020, p. 12830) for economic production.

In the 1940s, plastic production grew as a WWII material for equipment but also a new form of oil refining, catalytic cracking, was used to make high-octane jet fuel. Olefins, like propylene, are a byproduct that “became the vital feedstock for the production of petrochemicals and plastics” (Huber, Reference Huber2012, p. 304) and “Massive petrochemical plants sprung up next to oil refineries in the United States and Europe” (Mah, Reference Mah2022, p. 5). Plastic commodities expanded at scale (Huber), linking plastic Fordist capitalism and war.

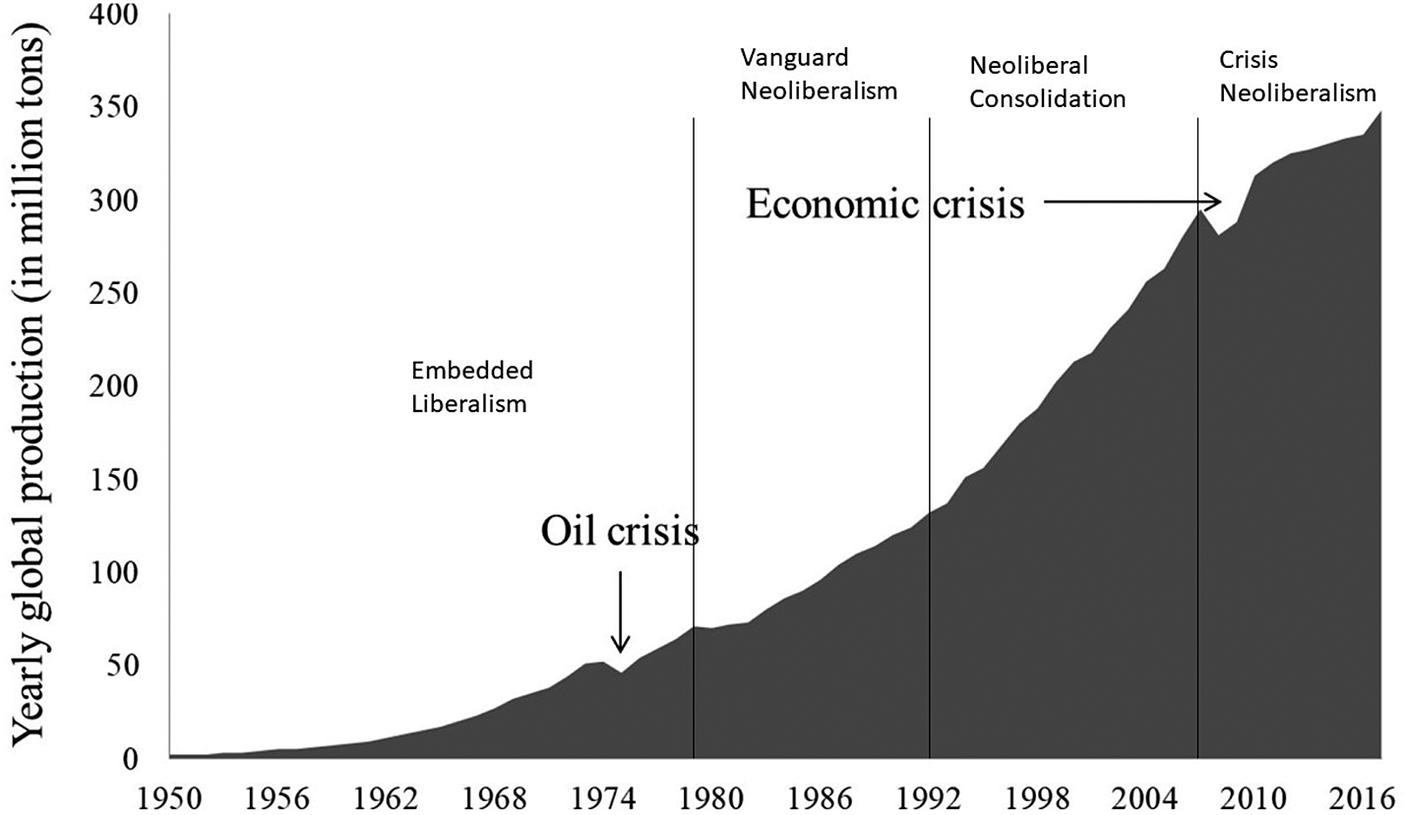

Plastic production intensifies again but much more dramatically in the neoliberal stage (1979–present) when plastics become the third most manufactured material behind cement and steel (Geyer, Reference Geyer and Letcher2020b; Rangel-Buitrago et al., Reference Rangel-Buitrago, Neal and Williams2022) and is seen as “inextricable” from modern living (Huber, Reference Huber2012, p. 307; see Figure 1). Neoliberalism puts the control of the economy primarily in private, not public, control (Centeno and Cohen, Reference Centeno and Cohen2012). Davidson (Reference Davidson2017) divides neoliberalism into three periods: the initial “vanguard” period (Reagan/Thatcher beginning), a period of consolidation where center-left parties adopt neoliberalism and solidifies neoliberal international hegemony, and crisis neoliberalism after the 2007 global recession. We see that the vanguard period increased the gross and pace of growth in plastic production, both of which grew again post-1992 until the 2007 crisis that temporarily slowed production (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Periodized plastic production. Adapted from da Costa et al. (Reference da Costa, Mouneyrac, Costa, Duarte and Rocha-Santos2020, p. 2) under CC BY.

Figure 1 shows that MPP part of the “Great Acceleration” – the exponential growth of problems like nitrogen pollution and biodiversity loss (McNeill and Engelke, Reference McNeill and Engelke2014) realized by the tendency to increase the ratio of products per unit of labor over time, hastening biophysical throughput in a treadmill (Stoner and Melathopoulos, Reference Stoner and Melathopoulos2015).

Plastic is a synthetic material that substitutes increasingly scarce natural resources and is “intrinsic” to the ToP (Foster et al., Reference Foster, Clark and York2011, p. 210) as much as post-War capitalism is intrinsic to plastic. ToP was first described by Alan Schnaiberg (Reference Schnaiberg1980) who recognized post-War capital investments greatly increased production necessitating equal increases in natural resources; also, the new production processes were energy and chemically intensive resulting in accelerating pollution, especially of synthetic materials like plastic. This means that the market partially evades a constraint described by van der Pijl (Reference van der Pijl, Albritton, Itoh, Westra and Zuege2001) who notes the regular phases of (1) original accumulation, (2) production, and (3) exhaustion, and then the process starts over again. Plastic is only becoming more abundant.

Successive cycles renew the process and the treadmill grows, also growing firm power and independence from government since the state increasingly depends on growth (Gould et al., Reference Gould, Pellow and Schnaiberg2015). While producers believe, “production is legitimately the exclusive province only of the owner/management/shareholder class,” (Gould et al., Reference Gould, Pellow and Schnaiberg2004, p. 303), steering production is essential to reducing MPP under ToP. Unfortunately, neoliberalism globalized the plastic flow, facilitating the transfer of waste to global South labor, markets, and ecosystems (Gould et al., Reference Gould, Pellow and Schnaiberg2004; Lewis, Reference Lewis2019).

While plastic helps avoid some natural resource exhaustion, it still consumes the ocean as a sink. Since the exhaustion of ecological sinks can interfere with production, I will call this contradiction “maximum pollution.” Maximum pollution is a field of obstacles that increasingly interfere with commodity production and accumulation as the pollution becomes progressively costly and unacceptable, like O’Connor’s (Reference O’Connor1991) “second nature.” Second nature is nature changed by capitalism, and even though it initially seems free, second nature later undermines capital accumulation, for example, mining the soil in agriculture. Further, second nature provokes social resistance with a self-aware civil society. Already, the increased attention from publics around the world has put the petrochemical industry on “high alert” as reported by Alice Mah:

‘We need to make plastic fantastic again,’ said a senior industry adviser in his keynote speech on the ‘Future of Polyolefins’ in January 2019. ‘We need to get the image of plastic in oceans out of the public’s mind’ (Mah, Reference Mah2021, p. 122).

Nevertheless, MPP is on the global agenda now, and the new treaty might embed the plastic flow. The treaty mandate calls for measures across the life cycle of plastic, which includes plastic production. It is not yet clear how this life cycle will be restrained or directed, however, MPP clearly requires authentic restraints, such as limits on the petrochemical industry, because it “endangers human health and causes disease, disability, and premature death at every stage of its long and complex life cycle” (Landrigan et al., Reference Landrigan, Raps, Cropper, Bald, Brunner, Canonizado, Charles, Chiles, Donohue and Enck2023, p. 71). However, will the treaty lean more on economic structures, or will it focus more on individual responsibility, like recycling? In other words, how will plastic become embedded, how much social protection will be instituted?

Embeddedness and social protection

Polanyi elaborated three concepts that help explain environmental crises – fictitious commodities, embeddedness, and double movements. Polanyi defines commodities as “objects produced for sale on the market” (p. 75). This means that things not produced for sale but are required for markets to function, like land (nature), labor, or money (Burawoy, Reference Burawoy2021 adds knowledge) are “fictitious commodities.” These require social institutions – social and ecological protections – to shield them from annihilation:

Undoubtedly, labor, land, and money markets are essential to a market economy. But no society could stand the effects of such a system of crude fictions even for the shortest stretch of time unless its human and natural substance as well as its business organization was protected against the ravages of this satanic mill (Polanyi, Reference Polanyi2001, pp. 76–77, emphasis in original).

Thus, economies must “always and everywhere” (Block, Reference Block2007, p. 5) be “embedded” in legal, cultural, and political restraints because a market economy will destroy itself without them. Current neoliberal governance has progressively thinned restraints: “the idea of the free market drives policies that are increasingly destructive,” a progression Stuart et al. (Reference Stuart, Gunderson and Petersen2020, p. 38, emphasis added) use to explain climate politics.

For example, “In disposing of a man’s labor power the system would, incidentally, dispose of the physical, psychological, and moral entity ‘man’ attached to that tag” (Polanyi, Reference Polanyi2001, p. 76). Similarly, if the market were the only authority, “Nature would be reduced to its elements, neighborhoods and landscapes defiled, rivers polluted, military safety jeopardized, the power to produce food and raw materials destroyed” (Polanyi, Reference Polanyi2001). Granovetter (Reference Granovetter1985) likened “disembeddedness” to the Hobbesian state of nature.

Polanyi argued societies react to the first movement of laissez faire to protect themselves through a second movement. These “double movements” were made up of a “wide range of social actors, to insulate the fabric of social life from the destructive impact of market pressures” (Block, Reference Block2008, p. 1). Further, these movements are “not simply national phenomena, but global phenomena” and laissez faire has been ascendant the past 200 years due to financial and military coercion from globally dominant powers, exported first from England and then the US (Block, Reference Block2008, p. 4).

However, Fraser (Reference Fraser2014) warns that Polanyi’s social protections are romantically communitarian and so as to avoid domination she adds a third movement of intersubjective consent. Nonetheless, she also argues that Polyani could never have known how dramatic the (holistic) social and ecological crisis would be (Stuart et al., Reference Stuart, Gunderson and Petersen2020 also make this point about climate change).

Another problem: Polanyi assumes a semi-autonomous public and state who comprehend a genuine public interest separate from economic elites, or “thick reciprocity” of meaningful relationships and a logic of solidarity beyond simple exchange (Block, Reference Block2008). If the public is too easily “purchased,” as Gramsci (Reference Gramsci and Buttigieg2011) believed, then there is a danger of a false counter-movement where the “protections” serve economic elites while appearing to solve a problem. For example, scholars (see, e.g., Ferguson, Reference Ferguson2018; Gunderson et al., Reference Gunderson, Stuart and Petersen2018; Stuart et al., Reference Stuart, Gunderson and Petersen2019, Reference Stuart, Gunderson and Petersen2020) have used this logic to critique carbon markets as false counter-movements that expand market power and protect fossil fuels. Avoiding a false counter-movement or an “empty institution” with no regulation (Dimitrov, Reference Dimitrov2019) will require a vigilant global civil. Just as in climate change, “a real solution” to MPP “would involve subordinating economic systems to social and environmental goals” (Stuart et al., Reference Stuart, Gunderson and Petersen2020, p. 36).

Stages of capitalist development

Here I review some of the more important liberal and Marxist brands of stage theory to put MPP in context as well as highlight broader global importance of authentic embedding of the plastic flow. The core tension between these two general orientations is over-embeddedness – how shall nature, labor, and money be distributed?

Modern liberal approaches

Enlightenment theorists like Mandeville, Locke, and Mill described social progress as a Eurocentric natural history (see Brewer, Reference Brewer1998). Smith (Reference Smith, Cannan and Cannan1976) thought evolving production methods, increased divisions of labor, and development of markets brought socioeconomic progress. Progress equaled economic growth and better material lifestyles, including luxury goods (Brewer, Reference Brewer1998). In Book IV of The Wealth of Nations, Smith elaborates on the “four-stage theory” defined by the mode of subsistence: hunting, pastoralism, farming, and commerce. This is explained in his discussion of a standing army (Chapter 1, Part 1) where each mode of subsistence requires different institutions that serve the specific needs of that stage. For example, “Among nations of hunters, the lowest and rudest state of society, such as we find it among the native tribes of North America, every man is a warrior as well as a hunter” (p. 213). A standing army is not needed. Pastoralists and farmers can form an army and subsist on their own. It is not until the commerce stage that this changes. If a carpenter joins an army, the carpenter has no subsistence on his/her own because “Nature does nothing for him, he does all for himself. When he takes the field, therefore, in defense of the public, as he has no revenue to maintain himself, he must necessarily be maintained by the public” (p. 217). Meanwhile, war becomes a “very intricate and complicated science” requiring a professional army. Smith’s four-stage theory explains that institutions need to solve problems that are incidental to progress (Harpham, Reference Harpham1984, p. 769). While Smith knew social protections could not be left to merchants, the main restraint was competition and institutions should be structured to increase the economic growth and natural freedom (see, e.g., Naggar, Reference Naggar1977), not restrain production.

Related, Meramveliotakis and Manioudis (Reference Meramveliotakis and Manioudis2021) argue that Mill was deeply impacted by the Scottish Enlightenment and Smith in particular. “Mill’s ‘stages theory of economic development’ is founded on the principle of succession and progress and its central premise ‘is the desire of increased material comfort’” which is brought to society through improvements in knowledge and then technology (Mill, Reference Mill1898; Meramveliotakis and Manioudis, Reference Meramveliotakis and Manioudis2021, p. 6).

Finally, both Rostow (Reference Rostow1960) and Organski (Reference Organski1965) proposed stages of economic development for poor countries to follow. For Rostow, “It is possible to identify all societies, in their economic dimensions, as lying within one of five categories” (p. 4):

-

1. Traditional society

-

2. Preconditions for take-off

-

3. Take-off

-

4. Drive to maturity

-

5. High mass-consumption.

Distancing from Marxism, Rostow states, “…although stages-of-growth are an economic way of looking at whole societies, they in no sense imply that the worlds of politics, social organization, and of culture are a mere superstructure built upon and derived uniquely from the economy” (p. 2). Economic changes are “the consequence” of political and social changes. The goal of institutions is to realize the “end of history” in mass consumption. Inequality between societies at different stages of production is natural, and pollution is an opportunity where “economic logic behind dumping a load of toxic waste in the lowest-wage country is impeccable” (former World Bank economist Lawrence Summers quoted in Foster, Reference Foster1993, online).

Still, both liberal and Marxist camps see history as linear and traditional societies are deemed backward (Chilcote, Reference Chilcote1994).

Liberal stage theory sees progress embodied in mass consumption and development. Problems growth are merely necessary nuisances – there is no maximum pollution. Notions of social protections are, as in Smith, guided by “the self-interest that lies at the heart of modern commercial society” (Harpham, Reference Harpham1983, p. 773). Thus, if the MPP treaty is made in the liberal view, and it almost certainly will be, it be less embedded with the distribution of land, labor, and money heavily favoring monopoly capital.

Marxist stage theories

Marxist theories see environmental problems, like MPP, as “metabolic rifts,” or disruptions in natural systems caused by capital accumulation processes. In ecological unequal exchange, nutrients from agricultural fields of the countryside become food for the urban core. When the nutrients are not replenished, the periphery is depleted to build the core and the human relation to the natural world is ruptured (Foster, Reference Foster1999). Metabolic rifts are always an imperial relationship. Global environmental problems are explained by the totalizing pursuit of profit, “subsuming all natural and social relationships” which “generates rifts in natural cycles and process…” (Foster et al., Reference Foster, Clark and York2011, p. 76).

The Uno School

Albritton (Reference Albritton2022), writing in the Uno tradition, the stages of capitalist development, “…consists of a more concrete set of interacting ideological, legal, and political practices dominated by a set of economic practices” (p. 5, 1). Albritton suggests four stages: mercantilism (1600–1775), liberalism (1740–1875), imperialism (1880–1914), and consumerism (1945–1975) where the dates indicate the “golden age” of each stage (p. 1). After consumerism, Albritton expects “disintegration of capitalism towards forms of barbarism that portend the end of human society as we have come to know it” through militarism and climate change – or a more humane socialism (p. 6). Uno (Reference Uno and Sekine2016) made considerable progress for stage theory through a thought experiment of a purely capitalist society where all relations are commodity relations and all noneconomic (e.g., use) value is either turned into commodity values or eliminated. Society operates through the dialectical logic of expanding capital and market imperatives (Sekine, Reference Sekine2020), that is, totally disembedded and set to devour itself and drown in waste.

The Regulation Approach School

In the “Regulation Approach” (RA) which “explores the interconnections between the institutional forms and dynamic regularities of capitalist economies,” Fordism plays an important role (Moulaert et al., Reference Moulaert, Swyngedouw and Wilson1988; Jessop and Sum, Reference Jessop and Sum2006, p. 3). The RA approach is attuned to the crisis tendencies of capitalism and attends to the historical ruptures of structure “as accumulation and its regulation develop in and through class struggle” (Jessop and Sum, Reference Jessop and Sum2006, p. 4). The accumulation type referred to as Fordism has four components:

-

1. Mass production of standardized goods under a technical division of labor and a Taylorist scientific management expectations.

-

2. A positive feedback between mass production and mass consumption, where economies of scale increase incomes and demand which lead to more investments and improved techniques that grow production. Not all firms need to be Fordist, but this second criteria means other related industries need to also increase their production, for example, the steel industry for car production.

-

3. It is a mode of regulation that includes, “an ensemble of norms, institutions, organizational forms, social networks, and patterns of conduct” that guide the Fordist firms, including Keynesian welfare standards such that “most citizens can share in the prosperity of economies of scale” (Jessop and Sum, Reference Jessop and Sum2006, pp. 60–62).

-

4. The broader social impacts are a normalized mass consumption of standardized commodities and a standardized set of collective services from a bureaucratic state/local government like education, unemployment, retirement, and health insurance. All of this normalizes ideals (nuclear family, private car ownership, suburban home).

In the post-War Fordist period, mass production began in earnest internationally, firms were regulated and were expected to be good “citizens,” currency exchange was regulated by the gold standard, and workers benefited from corporate profit with strong wages bolstered by unions (Moulaert et al., Reference Moulaert, Swyngedouw and Wilson1988). Ruggie (Reference Ruggie1982) called this period “embedded liberalism.” Plastic is mass-produced, but with restraint.

During this period, plastic production reached 2 Mt (Geyer, Reference Geyer2020a). As post-Fordist neoliberal institutions developed, plastic production grew by hundreds of times, for example, by 2015 the global 450 Mt of plastic was produced (Geyer, Reference Geyer2020a).

Nixon abandoned the gold standard in 1971 but neoliberalism was fully embraced by Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher who deregulated corporate obligations allowing the consolidated profit-making without shared benefit to communities or workers, increasingly less represented by unions. Meanwhile, social safety nets were reduced – all of which spurred yawning inequality (Jacobs and Myers, Reference Jacobs and Myers2014). As the post-Fordist global economy grew, “site-intensive factory machinery and fixed capital of ‘heavy modernity’ dissolve into outsourcing, batch production, and hypermobile capital” (Yaeger, Reference Yaeger2010, p. 523) – and plastic production grew at its fastest, most devastating, pace (Geyer, Reference Geyer2020a).

The Capital-Logic School

Related, in the Capital-Logic School (Hirsch, Reference Hirsch1978), the capitalist economy grows further from social control because of the internal logic of capital. This logic is to convert relations from noneconomic forms to commodity forms: “commodity form of relations between people and likewise between humans and nature is accepted as an unquestionable self-evident truth” (Altvater et al., Reference Altvater, Birgit and Scott1997, p. 454). Money as the super-commodity, “…enables all qualities to be reduced to one: it makes apples and pears, pneumatic drills and nappies the same and so renders them comparable on the market” (Altvater, Reference Altvater1997, p. 48). Thus, the Capital-Logic School sees capitalist development unfolding the internal logic of capital itself, and MPP can again be seen as a result of disembedded economic logic. This means that MPP and other environmental changes face the difficult realities of the, “actual governability of limited environmental space under the auspices (or in the context) of globalized, politically borderless, socially disembedded, and deregulated economic processes” (Altvater, Reference Altvater1999, pp. 47–48).

The Lenin School of imperialism and monopoly capital

Finally, the Leninist view that imperialism is the highest stage of capitalism (Lenin, Reference Lenin1939), has been extremely influential in later theorizing, such as Ernest Mandel’s theory of the “late capitalist” stage and the Uno School (McDonough, Reference McDonough1995). Preceded by Hilferding who proposed that finance capital – the combination of industrial and bank capital through the joint-stock company – was the highest stage because the pools of capital vastly expanded the scale of capitalism (Hilferding et al., Reference Hilferding, Bottomore, Watnick and Gordon2019). Hilferding argued that this expansion allowed for the creation of cartels and monopolies, protected by tariffs organized through capitalist political force; and undeveloped areas become increasingly valuable abroad, making war likely as strong states advance to claim new space through primitive accumulation. Lenin synthesizes these accounts to define the stage of imperialism as when:

-

1. the concentration of production through monopolies make a “decisive role in economic life”

-

2. banking and industrial capital pool together into a “financial oligarchy”

-

3. export of capital becomes central

-

4. “international monopolist capitalist associations…share the world among themselves”

-

5. “the territorial division of the whole world among the biggest capitalist powers is completed” (Lenin quoted in McDonough, Reference McDonough1995, p. 353)

Imperialism is a manifestation of monopoly capital pursuing ecological space and people to feed the commodification processes in a dynamic that would later inform the notions of dependency and underdevelopment in comparative politics, describing a flow of value-enriching wealthy core imperial states (Chilcote, Reference Chilcote1994). The reverse is also true: wealthy states export pollution, as they do plastic waste, to poorer countries who hope to capture some value in it (Bai and Givens, Reference Bai and Givens2021).

Lenin provides the foundation for Magdoff (Reference Magdoff1969), Sweezy (Reference Sweezy1970), and Braverman (Reference Braverman1998) – the “Monopoly School” which argues the concentration of capital into industrial oligopolies was the stage of capitalism from beginning of the 20th century. Yeros and Jha (Reference Yeros and Jha2020) write that the “concentration of capital persists today hand in hand with the escalation of primitive accumulation and war, while national sovereignty continues to fray in the peripheries…” (p. 78). Foster (Reference Foster2021) also applies the stage of monopoly capitalism as contemporary mode of accumulation that can help explain “contradictions specific to monopoly capitalism such as the growing role of waste in production” (abstract). Foster refers to monopoly capitalism as the advent of the modern giant corporation that no longer allows for competition from smaller, especially, family, firms; Schnaiberg (Reference Schnaiberg1980) adds that monopoly firms tend to have better control over their sources and processes, like petrochemicals. Indeed, some of the largest companies in the world are also among the largest plastic producers – for example, Dow Chemical, ExxonMobil, BASF (Plastics Technology, 2022), making MPP also a result of monopoly power. Monopoly capitalism grows the power and autonomy of large corporations and empowers them to push government for less regulation, and corporate power is all the more important in managing the plastic flow when governance is fragmented and the issue is complex and costly (Dauvergne, Reference Dauvergne2018; Mah, Reference Mah2022).

All the Marxist schools see something like MPP as a result of capital aggregating across stages where it increasingly abuses people and ecologies in larger and larger rifts.

Conclusion

Karl Polanyi imagined the development of capitalism through both the movement of laissez faire and its restraint in a double movement. Liberal stage theory sees mass consumption as human progress and problems that arise are necessary nuisances, embodying the first movement. Marxist stage theory embodies the second movement, warning that capital is ever striving to commodify everything. Polanyi, certainly over-confident that society would protect itself, did warn against the failure of the second movement which would result in a Polanyian nightmare and the coup de grace of a complete metabolic rift:

To allow the market mechanism to be sole director of the fate of human beings and their natural environment indeed, even of the amount and use of purchasing power, would result in the demolition of society (Polanyi, Reference Polanyi2001, p. 76).

For the plastic treaty to be effective, it must successfully embed plastic production, and restrain the market mechanism. Specifically, there will need to be serious restraints on monopoly capital in the petrochemical industry. Whether it does this or not will depend on whether global society lives up to Polanyi’s hope or if we pursue the Uno imaginary of universal commodity relations. From this stage of history, however, states and economic forces do not seem keen on anything but empty institutions (Dimitrov, Reference Dimitrov2019).

Open peer review

To view the open peer review materials for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/plc.2023.1.

Comments

Dear Editors,

This is a resubmission (remember a new invitation was created after initial decision was changed to R &R) for the inaugural issue.

I have uploaded my response to the reviewer but had to do it as “supplemental material” as there was no option for a response but I did not see it in the pdf the system produced, so I have added the response to the reviewer in the manuscript itself as I did not want to risk it not getting to the reviewer. I have also uploaded a track changes document as “supplemental material” for your review.

As noted in the response to the reviewer, who was really expert in this literature and really very helpful, I reconceptualized the approach given the suggestions as well as reorganized the paper to fully engage the suggestions. I have attempted to respond to each criticism and I would like to think this is a much improved paper, especially with the suggestion to better elaborate the issue of embeddedness, which has its own section now, positioned as a key tension. I have engaged the literature suggested as well, but also looking to related publications to those citations noted by the reviewer.

I appreciate the opportunity to rework this and hope it makes the mark. I have enjoyed working on this problem!

Peter Jacques