INTRODUCTION

Architectural sculpture and freestanding carved monuments marked urban landscapes across the pre-colonial Maya region. During the Classic period (a.d. 250–900), these artistic traditions demonstrated sufficient consistency in form, content, technique, and material over time and space to become a key component in scholarly definitions of lowland Maya culture. Such a singular view of these works, however, masks significant local differences in sculpting practices across the lowlands and through time, even within a single ancient city. Ongoing advances in Classic Maya archaeology and political history (Houk et al. Reference Houk, Arroyo and Powis2020; Martin Reference Martin2020), in turn, encourage more nuanced interpretation of how local production of stone sculpture was bound up in regional participation in cultural exchange and the institution of divine kingship (compare Earley Reference Earley2019; Golden et al. Reference Golden, Scherer, René Muñoz and Vasquez2008; Vázquez López Reference Vázquez López, Banach, Helmke and Źrałka2017).

In the western Maya lowlands, an area that we define as roughly delimited by Comalcalco in the far north, Tonala in the south and west, and the Usumacinta River Valley and San Pedro Mártir River floodplains in the east (Figure 1), Classic era sculptures exhibited great diversity in architectural placement, form, and hieroglyphic and iconographic content. Sculptural traditions varied systematically between major western political centers, most notably Palenque, Piedras Negras, Tonina, and Yaxchilan (see Clancy Reference Clancy2009; Miller Reference Miller and Houston1998; O'Neil Reference O'Neil2012; Tate Reference Tate1992). Each royal court and its attendant artisans developed a unique style amidst ongoing exchange with each other, spurring emulation and innovation across the region (Miller Reference Miller and Houston1998; O'Neil Reference O'Neil2012; Proskouriakoff Reference Proskouriakoff1950). By emphasizing distinct formats of freestanding and architectural sculpture, courtly artisans in the Maya west participated in the broader Classic Maya tradition of monumental production, but did so in very local forms—a practice that in some cases was a conscious elite strategy to “promote a specific set of memories and then to enter them time and again on the mental slate through both visual images and written texts” (Miller Reference Miller and Houston1998:194; see Earley Reference Earley2015; Golden et al. Reference Golden, Scherer, René Muñoz and Vasquez2008). Dynastic representatives not only memorialized their deeds on these monuments; they presented narratives that inscribed their community's place in the western Maya world (Miller Reference Miller and Houston1998:194).

Figure 1. Regional map showing location of Classic-period Maya political centers. Triangles indicate capitals governed by k'uhul ajaw; squares indicate capitals governed by ajaw. Map by Golden.

A key player in western Maya geopolitics, the Sak Tz'i' dynasty developed its own approach to stone sculpture that expressed the polity's position relative to neighboring allies and antagonists alike. Recent fieldwork at the archaeological site of Lacanjá Tzeltal has confirmed that it was the seat of the Sak Tz'i' polity during much of the Late Classic period (a.d. 600–900; Golden et al. Reference Golden, Scherer, Houston, Schroder, Morell-Hart, Álvarez, Van Kollias, Talavera, Matsumoto, Dobereiner and Firpi2020). Hieroglyphic inscriptions proved critical to identifying Sak Tz'i' epigraphically and, ultimately, to locating its major center on the ground (Golden et al. Reference Golden, Scherer, Houston, Schroder, Morell-Hart, Álvarez, Van Kollias, Talavera, Matsumoto, Dobereiner and Firpi2020; see Anaya Hernández et al. Reference Anaya Hernández, Guenter and Zender2003; Bíró Reference Bíró2005). But what can those same monuments tell us about the polity's position in the western Maya region, beyond their linguistic contents? More broadly, too, what can practices of sculpting stone at Lacanjá Tzeltal reveal about the formation of Classic Maya political identity and the relationship between political and cultural exchange? Placing its sculptural tradition in western Maya context reveals how Lacanjá Tzeltal's Classic era community employed monumental sculpture to simultaneously participate in regional politics and construct a distinct political identity. Sak Tz'i' sculptors engaged with other western traditions but consciously deviated from them in key facets, an approach that paralleled the polity's struggle to establish its autonomy in a geopolitical landscape dominated by its neighbors.

Following a brief discussion of approaches to innovation and traditionalism in Classic Maya art, we discuss the recently documented corpus of monuments at Lacanjá Tzeltal, Chiapas, elaborating on initial descriptions by Laló Jacinto (Reference Laló Jacinto1998) and Golden and colleagues (Reference Golden, Scherer, Houston, Schroder, Morell-Hart, Álvarez, Van Kollias, Talavera, Matsumoto, Dobereiner and Firpi2020) (Table 1). We examine evidence for looting at the site and as yet unsuccessful attempts to draw connections to unprovenanced Sak Tz'i' inscriptions. Subsequently, we present a paleographic analysis of Lacanjá Tzeltal Panel 1 that situates its hieroglyphic features within the Sak Tz'i' corpus and relates it to regional trends in Classic Maya hieroglyphic writing, especially to the tradition at Palenque. Finally, we address the implications of the sculptural data for understanding Lacanjá Tzeltal's place in the Sak Tz'i' realm and the polity's position in the western Maya region. In addition to offering insights into the kingdom's cultural history and political identity, we voice lingering questions that will guide future fieldwork at the site.

Table 1. Summary of sculpted stone monuments documented to date at Lacanjá Tzeltal, Chiapas.

SCULPTURE, INNOVATION, AND POLITICAL IDENTITY IN THE MAYA WEST

Stone sculptures loom large in archaeological interpretations of the ancient past as both expressions and instruments of political assertion, ritual participation, and social identity. They convey meaning through their physical presence in the world, but are also mobilized in meaning-making activities of cultural, political, or ceremonial import. Through incorporation into performances of political power, social integration, or ritual, sculpted monuments are “culturally marked as being a certain kind of thing” and thus acquire a contextually contingent meaning (Kopytoff Reference Kopytoff and Appadurai1986:64; see DeMarrais et al. Reference DeMarrais, Castillo and Earle1996; Inomata Reference Inomata2006). Often their significance is intimately tied to social, religious, or political authority as “lieux de mémoire” in the sense of Nora (Reference Nora1989:7), sites “where memory crystallizes and secretes itself” in visible expressions of cultural and political identity (compare Stuart Reference Stuart1996; Wu Hung Reference Hung1995). They thus become what Barth (Reference Barth and Barth1969:14) calls “diacritical features” or explicit loci of group identity, whether at the time of initial production or retrospectively among their inheritors.

Monumental sculpture is never an unequivocal tool of elite authority, however. The relative constancy of sculpted works’ form belies “their capacity for metamorphosis, an endless recycling of their meaning and an unpredictable proliferation of their ramifications” (Nora Reference Nora1989:19). As is evident from ongoing contestation of the past and future of Confederate statues in the United States today (Cox Reference Cox2021; Winberry Reference Winberry1983), sculptures are iteratively reinterpreted over time, and exposition inherently makes them vulnerable to resignification, sometimes in unanticipated ways. They may be mobilized to challenge or relocate power—in some cases, the same power that they were meant to represent—through subversive “counter-monumental performances” that provoke “disturbance, contestation and irresolution” of monuments’ meaning and role in memory-making (Moshenska Reference Moshenska2010:7, 23; see also O'Neil Reference O'Neil2009; Osborne Reference Osborne2017; Young Reference Young1992). Classic Maya viewers, too, recognized and exploited this potential, resignifying monumental expressions of elite identity through intentional destruction, defacement, looting, or displacement (see Golden et al. Reference Golden, Scherer, Kingsley, Houston, Escobedo, Iannone, Houk and Schwake2016; Harrison-Buck Reference Harrison-Buck, Iannone, Houk and Schwake2016; Just Reference Just2005; Martin Reference Martin, Colas, Delvendahl, Kuhnert and Schubart2000, Reference Martin2017).

The significance of monumental sculpture is grounded, in part, in the cultural dynamics of innovation and conservatism underlying its production. Whereas innovation entails change through the “adoption of an invention on a collective scale” (Roux Reference Roux and Shennan2010:217), conservatism or traditionalism retains familiar practices in the face of alternatives so that “adoption lag[s] far behind awareness-knowledge of a new idea” (Rogers Reference Rogers1983:250; compare Dietler and Herbich Reference Dietler and Herbich1989; Frieman Reference Frieman2021; Weissner Reference Weissner1997). Both phenomena, however, are best understood as scalar. No tradition arises ex nihilo from innovations alone, and even the most conservative traditions entail a baseline level of variability in production: “in every case that one can think of, copying involves repetition … But in this act of repetition … something else happens. Difference manifests itself in repetition and marks a transformation that happens within repetition” (Boon Reference Boon2010:91; compare Inoue Reference Inoue2018; Wong Reference Wong2013).

Yet conservatism and innovation are as much sociopolitical phenomena as they are technological developments. The decision to create new practices or to adopt those invented by others “is not a binary choice, but is a multi-staged process deeply embedded” in sociocultural context (Frieman Reference Frieman2021:80). Archaeologists have tended to assume that socially or politically central communities were primary sites of innovation (Champion Reference Champion1989; Chase-Dunn and Hall Reference Chase-Dunn and Hall1991; Rowlands et al. Reference Rowlands, Larsen and Kristiansen1987). Geographically or politically marginal ones, in contrast, are often said to react to changes coming in rather than generating their own (Hartz Reference Hartz1969; Kopytoff Reference Kopytoff and Kopytoff1987). But more recent research emphasizes peripheries’ own innovative potential as places of cultural encounter whose artistic developments may influence the center (Bhabha Reference Bhabha1994; Eberl Reference Eberl2018:65–99; Lightfoot and Martinez Reference Lightfoot and Martinez1995; Stein Reference Stein2002). In some cases, Ogundiran (Reference Ogundiran2014:21) argues, the innovative character of communities who occupy what he calls “crossroads interstices” may actually provoke intervention by expansionist neighbors.

Early research on core–periphery cultural tensions in Classic Maya contexts highlighted the southeastern lowlands, where material practices integrated Maya and non-Maya traits (Schortman and Urban Reference Schortman and Urban1994; Schortman et al. Reference Schortman, Urban and Ausec2001). At a regional level, the murals of Cacaxtla offer a striking case of artists innovating a local style inspired by foreign—in this case, Central Mexican and lowland Maya—canons (Brittenham Reference Brittenham2015; Foncerrada de Molina Reference Foncerrada de Molina and Robertson1980; Kubler Reference Kubler and Robertson1980). But innovative dynamics of marginality–centrality played out more locally, too, in interactions between Maya polities of varying cultural and political influence (Halperin and Martin Reference Halperin and Martin2020; Iannone Reference Iannone2011). Sculptors at the minor polity of Chinkultic, for instance, engaged with iconographic trends from powerful peers in the Usumacinta River Basin, even as Chinkultic elites remained largely disengaged from those political networks (Earley Reference Earley2015, Reference Earley2019). In constructing an authority fundamentally based on a warrior identity, they adopted representational modes from distant neighbors but combined them in distinct ways or created local variants to establish a sculptural style that was “both innovative and consistent” (Earley Reference Earley2019:304). When such stylistic positioning is undertaken consciously, the extent to which an artistic community perceives itself—or is perceived by others—as adhering to existing practices or innovating new ones can be core to its cultural identity (compare Dietler and Herbich Reference Dietler and Herbich1989; Guernsey Reference Guernsey2012; Schortman Reference Schortman1989).

As noted, the western area of the Classic Maya world stands out for great diachronic and, especially, synchronic variability in sculptural traditions. Stelae (often paired with altars) were the predominant monumental form in the Central Peten, where major sites such as Tikal or Calakmul are known for their largely planar, rectangular, upright stones sculpted in bas-relief (see Jones and Satterthwaite Reference Jones and Satterthwaite1982; Marcus Reference Marcus1987). But these differed notably from the high-relief, in-the-round stelae representing individuals at Tonina and from the sculpture of Piedras Negras, where innovative bas-relief stelae were canvases for scenes of courtly ritual (O'Neil Reference O'Neil2012; Proskouriakoff Reference Proskouriakoff1950:118–119, 121, 136, 138). Architectural panels, in turn, were increasingly carved in high relief at Piedras Negras but in bas-relief at Palenque and Pomona (Stuart Reference Stuart1996:150; see McHargue Reference McHargue1995:205–243; Proskouriakoff Reference Proskouriakoff1950:136–137), whereas the Yaxchilan kingdom established itself as master of the inscribed stone lintel (Golden et al. Reference Golden, Scherer, René Muñoz and Vasquez2008:263; Proskouriakoff Reference Proskouriakoff1950:147).

Even within the diverse landscape of the west, however, Sak Tz'i' represented an outlier—a status that we argue was an intentional, sculptural expression of the polity's relative autonomy in regional geopolitics. The title ajaw (“lord”) denoted a class of high-ranking nobility whose numerous members included both rulers, including that of Sak Tz'i', and non-rulers (Houston and Stuart Reference Houston, Stuart, Inomata and Houston2001; Martin Reference Martin2020:238–248). K'uhul ajaw (“holy lord”), in contrast, was reserved for a more exclusive rank and is considered to have been both a specific statement of rulership and a general claim to power and authority (Houston and Stuart Reference Stuart1996; Martin Reference Martin2020:69–77; Mathews Reference Mathews and Patrick Culbert1991). For a polity to be ruled by a mere ajaw was not unusual, especially in the western region. Other kingdoms whose ajaw rulers lacked the k'uhul prefix included neighboring La Mar and Bonampak, who by the eighth century were close allies, if not subordinates, of Piedras Negras and Yaxchilan, respectively (Mathews Reference Mathews and Robertson1980; Zender Reference Zender and Stone2002), as well as more distant Lakamtuun, a polity whose history remains poorly understood but that was likely based farther south along the Lacantún River (Stuart Reference Stuart1996:154, Reference Stuart2007; see Rivero Torres Reference Rivero Torres1992; Schroder et al. Reference Schroder, Golden, Scherer, Murtha and Firpi2019).

Yet the Sak Tz'i' polity was highly divergent from its ajaw-governed peers, by virtue of its prominence in foreign inscriptions and its apparent maintenance of political sovereignty throughout the Classic era. Moreover, the great quantity and diversity of Sak Tz'i' stone monuments are unprecedented for a kingdom ruled by an ajaw who lacked the k'uhul prefix claimed by most independent kings during the Late Classic period. Lacanjá Tzeltal's sculptures resembled other western Maya productions in form and iconographic and hieroglyphic content, a testament to its artisans’ awareness of regional sculptural trends. Nevertheless, as we outline below, local monumental experimentations demonstrate that this lesser court functioned as a center of cultural innovation, and that the lords of Sak Tz'i' may have fostered such distinction to underscore their independent political identity.

PRIOR RESEARCH ON THE KINGDOM OF SAK TZ'I'

For nearly three decades, the Sak Tz'i' kingdom was known only from stone inscriptions in private and museum collections in western Europe and North America (Table 2), as well as from occasional references to actors described as Sak Tz'i' lords on monuments at Bonampak, El Cayo, Piedras Negras, Tonina, and Yaxchilan (Beliaev and Safronov Reference Beliaev and Safronov2009; Bíró Reference Bíró2005; Houston cited in Stuart Reference Stuart1987:10). In addition to offering initial clues concerning the kingdom's geographic location (Anaya Hernández et al. Reference Anaya Hernández, Guenter and Zender2003; Schele and Grube Reference Schele, Grube and Schele1994:111, 116), the unprovenanced inscriptions indicated that Sak Tz'i' rulers were independent actors who exercised prominent influence on regional politics but never achieved the hegemonic power of neighboring dynasties whose kings claimed the lofty k'uhul ajaw title. Identification of the kingdom's capital thus promised to fill in significant holes in the epigraphic and archaeological record of the western lowlands (compare Graham Reference Graham2010:453–467, 491–496; Guenter Reference Guenter2005; Scherer et al. Reference Scherer, Golden, Houston and Doyle2017).

Table 2. Unprovenanced monuments that have been attributed to the Sak Tz'i' polity.

The discovery in 2014 of the well-preserved Panel 1, whose hieroglyphic text includes the polity's emblem glyph or dynastic title and the name of a Sak Tz'i' ruler, K'ab Kante' (Golden et al. Reference Golden, Scherer, Houston, Schroder, Morell-Hart, Álvarez, Van Kollias, Talavera, Matsumoto, Dobereiner and Firpi2020:78–80; see Houston cited in Stuart Reference Stuart1987:10), along with subsequent archaeological research at the site, now permit us to say that Lacanjá Tzeltal was once a seat of the Sak Tz'i' dynasty, though it was unlikely to have served this role throughout the entire Classic period. The royal court probably established itself at Lacanjá Tzeltal after a.d. 600, building their pyramids and palaces atop earlier ruins (Golden et al. Reference Golden, Scherer, Houston, Schroder, Morell-Hart, Álvarez, Van Kollias, Talavera, Matsumoto, Dobereiner and Firpi2020). Initial excavations indicate that Lacanjá Tzeltal was occupied by the Middle Preclassic period (750–450 b.c.; Golden et al. Reference Golden, Scherer, Houston, Schroder, Morell-Hart, Álvarez, Van Kollias, Talavera, Matsumoto, Dobereiner and Firpi2020:77, 81). However, the absence of Early Classic (a.d. 250–600) materials suggests little to no occupation during that time, after which the site again saw significant, if shallow, construction during the Late Classic era, before final abandonment sometime in the Terminal Classic period (a.d. 800–900).

THE MONUMENTS OF LACANJÁ TZELTAL

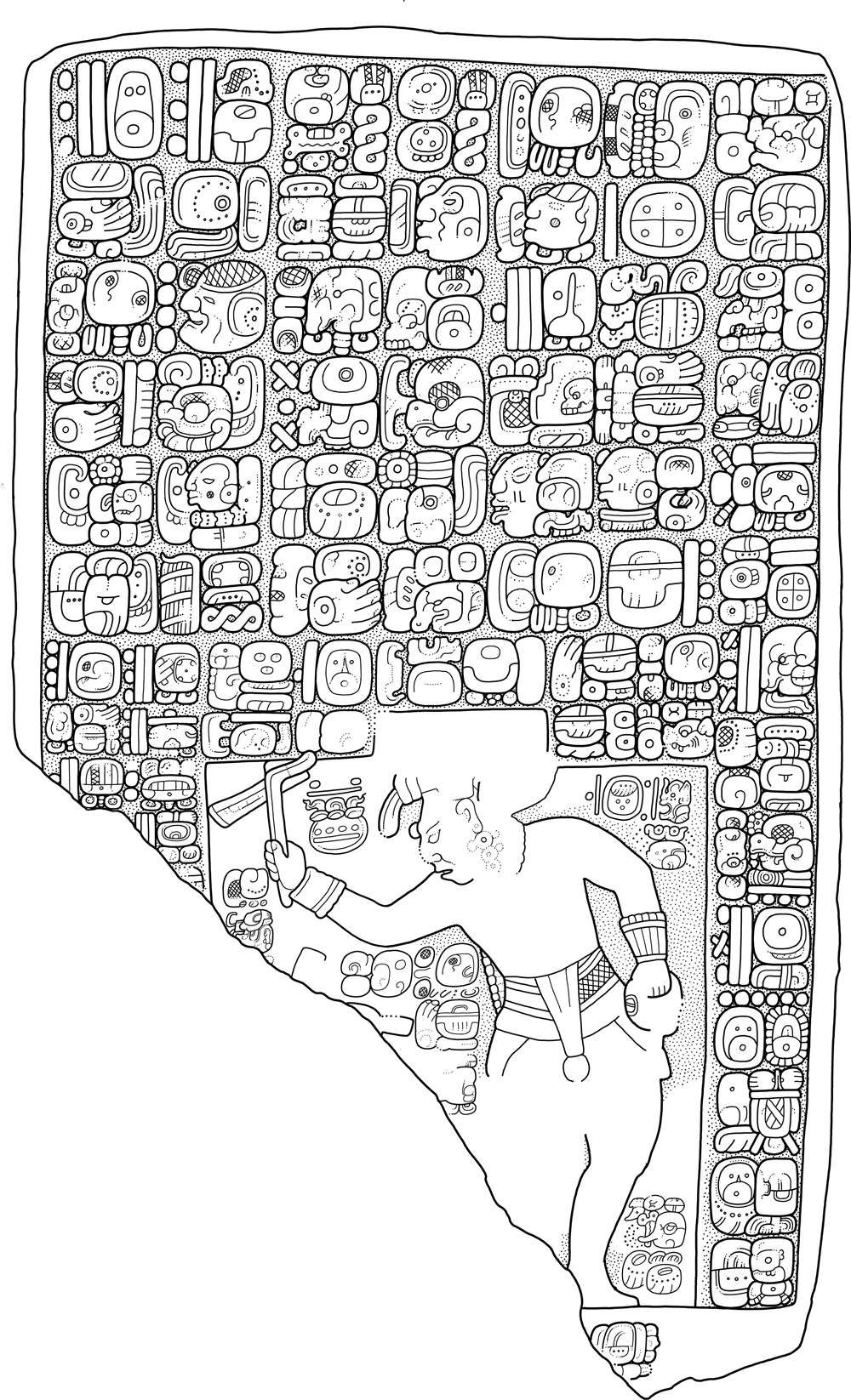

To date, 58 stone monuments and 12 monumental fragments have been documented at Lacanjá Tzeltal (Table 1). Although the settlement is built over a travertine substrate, the nearby hills are limestone and were likely the source for the medium- to fine-grain limestone from which all the monuments were carved. Eleven sculptures have an irregular form that defies easy categorization, for which reason we have labeled them as Miscellaneous Sculpted Stones (MSS), following the example of prior archaeological projects such as that at nearby Piedras Negras (Satterthwaite Reference Satterthwaite1965; compare Stuart and Graham Reference Stuart and Graham2003). An additional eight remain partially buried and are identified as Unclassified Monuments pending future excavation. Panel 1 is the best-preserved sculpture at Lacanjá Tzeltal and retains the only legible multi-glyph inscription (Figure 2; see Golden et al. Reference Golden, Scherer, Houston, Schroder, Morell-Hart, Álvarez, Van Kollias, Talavera, Matsumoto, Dobereiner and Firpi2020:78–80). Most other monuments are badly eroded; few preserve discernible traces of iconography, and only five present hieroglyphs that are still (partially) recognizable, although we have not yet been able to turn over fallen monuments to equally document all their surfaces.

Figure 2. Lacanjá Tzeltal Panel 1. The central image shows the eighth-century Sak Tz'i' lord K'ab K'ante' as the rain god Chahk. Drawing by Houston.

Prior to our local collaboration, four monuments (Panel 1; Stelae 14, 16, 24) had been moved by the landowner to protect them, and their original positions are not known. The other sculptures remain on site, where most are concentrated on Plaza Muk'ul Ton (“Monuments Plaza” in Tzeltal, the language of the adjacent modern community) or in one of three monument piles (Figure 3). Fourteen monuments are likely still in situ (Altars 1, 2, 5, 11; Stelae 2–5, 11, 13, 15, 21, 22; MSS 8). The only ones that are unequivocally associated with each other, however, are Stelae 3–5, whose aligned bases suggest that they were originally erected in a row on the north platform of Str. E5-13, facing Plaza Muk'ul Ton. Most of the site's sculptures seem to have been moved from their original placement, as will be discussed below.

Figure 3. Map of Lacanjá Tzeltal site core, indicating the locations of documented monuments. Monument Piles 1–3 are enclosed in red and numbered. Map by Atasta Flores Esquivel, modifications by Matsumoto.

The extent of damage to the monuments at Lacanjá Tzeltal reflects long-term exposure of the carved surfaces, differences in surface preparation or carving, and, in some cases, targeting by looters. Of those on site, 48 monuments and all 12 monumental fragments are still partially or completely exposed to the elements, and most remain vulnerable to further damage through looting or disturbance by local cattle. Furthermore, numerous sculptures on site at Lacanjá Tzeltal bear scars from hand or chainsaws with which fragments were removed in the recent past (Table 3). They thus present an opportunity to explore links to unprovenanced inscriptions that have been attributed to the kingdom of Sak Tz'i' (Table 4), which would significantly improve our understanding of Lacanjá Tzeltal's settlement history and position in the Classic Maya political sphere (see Bíró Reference Bíró2005; Golden et al. Reference Golden, Scherer, Houston, Schroder, Morell-Hart, Álvarez, Van Kollias, Talavera, Matsumoto, Dobereiner and Firpi2020). However, we have been unable to establish any definitive associations thus far.

Table 3. Monuments at Lacanjá Tzeltal from which portions were previously extracted with metal tools.

Table 4. Dimensions of unprovenanced Sak Tz'i' monuments.

Arguably the most significant unprovenanced monuments ascribed to the Sak Tz'i' polity are the so-called Denver and Brussels Panels, two sections of what was originally a larger hieroglyphic narrative (Figure 4; Berlin Reference Berlin1974). Their text details military victories and political machinations of a Sak Tz'i' ajaw, likely in the late seventh century (Bíró Reference Bíró2005:2–8; Schele and Grube Reference Schele, Grube and Schele1994:111, 116). The most obvious candidate at Lacanjá Tzeltal for the carcass of either or both panels is the truncated Stela 13 whose base remains in situ, but it is impossible to know how tall that stela originally stood. Another possibility is that either the Denver or Brussels Panel originally belonged to Stela 9, a columnar monument whose front was shaved off (Figure 5; Table 4). However, each of Stela 9's two extant fragments preserves a finished end, and their cut surfaces reach a combined height of just 144 cm, well short of either unprovenanced panel (Table 4).

Figure 4. (a) Denver Panel. Photo AC.8658-014 © Denver Museum of Nature and Science; (b) Brussels Panel. Photograph © RMAH, Brussels. The unprovenanced panels, which record mid-seventh-century political relations between Sak Tz'i' and its neighbors La Mar and Ak'e, were presumably part of a larger text that is now lost.

Figure 5. North fragment of Lacanjá Tzeltal Stela 9, a columnar monument whose far end and face were cut off and removed by looters. Photograph by Matsumoto.

We have yet to confidently identify a Lacanjá Tzeltal sculpture with a more quadrilateral outline and looting scars that could represent the carcass of any of the other monuments that have been attributed to Sak Tz'i' (Table 4). Although more sculptures may well be recovered from the site over the course of future investigations, it is also possible that some of the unprovenanced pieces were produced elsewhere. Prior scholarship proposed Plan de Ayutla as a likely candidate for the seat of the Sak Tz'i' court (Anaya Hernández et al. Reference Anaya Hernández, Guenter and Zender2003; Bíró Reference Bíró2005:13–14, 31–32; Martos López Reference López, Alberto, Golden, Houston and Skidmore2009), and Golden and colleagues (Reference Golden, Scherer, Houston, Schroder, Morell-Hart, Álvarez, Van Kollias, Talavera, Matsumoto, Dobereiner and Firpi2020) posit that Lacanjá Tzeltal may well have been one of two or more political centers over the course of the polity's history (compare Houston Reference Houston2016; Martin Reference Martin2005). The unprovenanced monuments’ origin(s) could thus reflect a history of transporting stone sculptures between Sak Tz'i' capitals or, perhaps, a legacy of monumental production at an unknown subsidiary site (Golden et al. Reference Golden, Scherer, Houston, Schroder, Morell-Hart, Álvarez, Van Kollias, Talavera, Matsumoto, Dobereiner and Firpi2020:Table 1).

LACANJÁ TZELTAL MONUMENT PILES

One of the more enigmatic features of Lacanjá Tzeltal concerns the distribution of its sculptural corpus. Significant quantities of extant sculptures are concentrated in three piles, designated areas in the site core where monuments, both fragmented and whole, have been heaped in front of the remains of larger buildings (Figure 3). They contain not only sculptured pieces that have been cataloged as monuments (see Table 1), but also worked stones that appear to have been more architectural in nature. According to conversations with the landowner and his older brother (their grandfather originally acquired the land in the 1960s, when it was still forested), the piles have been there for as long as they can remember and have not accumulated as the result of recent activity from farming, ranching, or looting.

Monument Pile 1 is located on Plaza Muk'ul Ton at the corner of Str. E5-13 and E5-14 (Figure 6). Its contents are primarily distributed among two concentrations, a larger one to the north and a smaller one to the south, separated by a rounded depression. It is the smallest of the three piles and has the highest proportion of architectural remains and only four documented monuments: Altar 3, Stelae 6 and 7, and Unclassified Monument 10. Monument Pile 2 is positioned on Plaza Ts'ahk (“Wall Plaza”) in front of the south side of Str. E-13, arranged in a rough half-circle along the edge of a depression that lies immediately to the south (Figure 7). More obviously than the others, Pile 2 is located next to and on top of an architectural mound. However, it remains unclear whether this or other architecture here was originally associated with the pile's monumental sculptures, which include Altars 6, 8, and 9; Stelae 17 and 18; MSS 3–6 and 9–11; and Unclassified Monuments 1–9. Finally, Monument Pile 3 is directly associated with the remains of Str. E5-18 and located in front of the north side of the platform denominated Str. E5-17 (Figure 8). Like Pile 1, its contents are roughly divided into two south and north concentrations.

Figure 6. Monument Pile 1. The white ruler south (to the left) of Altar 3 provides a scale of 2 m. Photograph and photogrammetric model by Matsumoto.

Figure 7. Monument Pile 2. The white ruler west of (above) Stela 17 provides a scale of 2 m. Photograph by Matsumoto; photogrammetric model by Golden.

Figure 8. Monument Pile 3. The white ruler between Altar 10 and Fragment 9 provides a scale of 2 m. Photograph and photogrammetric model by Matsumoto.

It is unlikely that the monuments in these piles rest in their original positions, but their initial contexts and circumstances of relocation remain unclear, as does whether the piles were created in pre-colonial times or more recently (see also Satterthwaite Reference Satterthwaite1958:58). The Lacanjá Tzeltal piles clearly differ from the workshops excavated at Xultun, where archaeologists discovered a series of monumental stone blocks abandoned in the process of quarrying, along with quarriers’ tools (Clarke Reference Clarke2020). Given their apparently haphazard composition and the monuments’ variable states of intactness, the piles may represent ancient monument dumps, such as those identified at Kaminaljuyu (Parsons Reference Parsons1986:6–7, 52–54) or, on a smaller scale, at Tikal (Jones and Satterthwaite Reference Jones and Satterthwaite1982:61). Considering that the region was largely uninhabited following the Classic-period abandonment, aside from semi-mobile Lacandon communities of the historic era, it is tempting to see the piles as acts of desecration associated with the Sak Tz'i' dynasty's collapse. Such ninth-century, post-collapse movement of sculptures is documented at Piedras Negras, where the site's small column altars were gathered and placed in Str. O-7 (Golden et al. Reference Golden, Scherer, Kingsley, Houston, Escobedo, Iannone, Houk and Schwake2016:118; Satterthwaite Reference Satterthwaite, Weeks, Hill and Golden2005d [1958]:332–338). Indeed, it is difficult to imagine why later Lacandon inhabitants would have been compelled to pile up the monuments (compare Stanton et al. Reference Stanton, Brown and Pagliaro2008), which include many but not all of the site's smaller, more mobile sculptures.

Nonetheless, only one sculpture between the piles at Lacanjá Tzeltal, MSS 1 in Pile 3, displays clear cuts from a metal tool, either scars from attempted looting or idle knocks from passing agriculturalists (Figure 9). The dispersed surface burning visible on some sculptures likely reflects recent slash-and-burn agricultural practices at the site, not the residue of wanton destruction. We thus refer to these assemblages neutrally as “piles” rather than “dumps,” because even if they did result from ceremonial activity, the ambiguity of its archaeological signature requires more evidence than is currently available to distinguish between “reverential” or “desecratory” behavior (Pagliaro et al. Reference Pagliaro, Garber, Stanton, Brown and Stanton2003:76). We do hope, however, to address these questions through future excavations, which may reveal more information about known monuments, additional sculptures that are still buried, or insights into the piles’ origin and relation to adjacent architectural features.

Figure 9. Miscellaneous Sculpted Stone 1 at Lacanjá Tzeltal. The unusually-shaped sculpture is the only one among the three monument piles with clear cuts from metal tools, but it nonetheless appears to be intact. Photograph by Matsumoto.

SCULPTURAL FORM

The sculptural corpus of Lacanjá Tzeltal is at once very typical of and notably divergent from Classic Maya regional trends. The stela is the most common sculpted form at Lacanjá Tzeltal, and many stelae were originally paired with altars, echoing Central Peten conventions but differing from nearby Piedras Negras or Yaxchilan. Yet other works at Lacanjá Tzeltal are morphologically very unusual, almost experimental compared to neighboring centers. The most notable outlier is MSS 1, a cylindrical monument with one tapered end and traces of carving on its underside (Figure 9), but other components of the Lacanjá Tzeltal corpus show more systematic deviations from typical Classic Maya traits. In the following, we highlight three especially striking phenomena: columnar sculptures, so-called squat monuments, and use of a single ballcourt altar. All these practices find analogues at other Classic Maya centers but their combination at Lacanjá Tzeltal is unique, underscoring the community's cultivation of an identity that was both politically and culturally distinct from its neighbors. Moreover, they offer inroads into better understanding sculptural monumentality as an expression of and instrument in western Maya sociopolitical relations.

Columnar Monuments

Lacanjá Tzeltal features five columnar monuments, which have been classified as Stelae 2 and 8–11 and demonstrate conspicuous differences in circumference, ranging between 155 cm (Stela 2) and 310 cm (Stela 8), as well as in height, varying from 114 cm (Stela 10) to 256 cm (Stela 2) in their present states (Figure 10; Table 5). Although all five are fragmented and broken along their vertical axes and three manifest scars from looting, three still retain traces of surface carving, with only glyphs on Stela 11 and images of standing figures and hieroglyphic inscriptions on Stelae 2 and 10 (Figure 10). Only two, Stelae 10 and 11, are still standing in situ. However, the landowner and other local members of the field team commented that they had seen other, similar monuments at the acropolis that may now be buried under rubble, suggesting that additional sculpted columns remain to be located.

Figure 10. Lacanjá Tzeltal Stela 2, a columnar monument with eroded hieroglyphs and a standing figure. The upper portion of the stela's carved face has been looted. (a) Photograph and (b) photogrammetric model by Matsumoto.

Table 5. Columnar monuments at Lacanjá Tzeltal.

There are few documented examples of tall, freestanding, columnar monuments in the Maya region generally and in the western zone in particular. A basalt column erected at Naranjo in the valley of Guatemala may date to the mid-eighth century b.c. and may thus represent the earliest example of this form in the Maya area (Arroyo cited in Stuart Reference Stuart, Guernsey, Clark and Arroyo2010:285, Figure 12.1b). In general, however, erection of larger columns as freestanding monuments is better attested in northern Yucatán sites such as Sayil and Uxmal (Earley Reference Earley2015:162–163; see Pollock Reference Pollock1980). Within the western area, Stela 2 from Santa Elena Poco Uinic has what Palacios (Reference Palacios1928:123) describes as a “pillar-like shape,” although he does not include measurements. One probable column altar now in the Saint Louis Art Museum, dating to a.d. 715 and possibly originating from Bonampak, approximately 40 km southeast of Lacanjá Tzeltal, stands at just 57 cm tall and has a maximum diameter of 23 cm (Miller and Martin Reference Miller and Martin2004:141, Plate 172; compare Earley Reference Earley2019:Figure 16c). Such diminutive, drum-like altars are in fact characteristic of the Yaxchilan kingdom, generally standing no more than some 50 cm tall (Grube and Luin Reference Grube and Luin2014; Tate Reference Tate1992:185, 204, 220, 229, 231, 235). A taller example is found at Piedras Negras, in contrast, where the fragmented, columnar Stela 46 measures 51–57 cm in diameter and 157 cm in height (Morley Reference Morley1938:77). Morley (Reference Morley1938:77–78) compared it with the site's columnar altars based on shape but noted that Stela 46 differed by virtue of its eroded inscription, much greater height, and lack of direct association with a stela. Yet the columnar monuments at Lacanjá Tzeltal are taller still than the column altars at Piedras Negras (Golden et al. Reference Golden, Scherer, Kingsley, Houston, Escobedo, Iannone, Houk and Schwake2016:118; Satterthwaite Reference Satterthwaite, Weeks, Hill and Golden2005c [1944], Reference Satterthwaite, Weeks, Hill and Golden2005d [1958]:332–338) or even more distant Tikal (Jones and Satterthwaite Reference Jones and Satterthwaite1982:83–85).

One inspiration or natural analog for upright, columnar monuments may have been speleothems. Caves were central to Classic Maya cosmology as places of emergence and interface with the underworld and its denizens (Bassie-Sweet Reference Bassie-Sweet1996; Brady Reference Brady1989; Brady et al. Reference Brady, Scott, Neff and Glascock1997; Thompson Reference Thompson1959). As Bassie-Sweet (Reference Bassie-Sweet1991:82–84, 110–126) first proposed, speleothems were ritually significant precisely because of their physical links to these spaces (see also Brady et al. Reference Brady, Scott, Neff and Glascock1997). Some were clearly modified in situ by ancient visitors, but others were occasionally relocated to the settlement core (Brady et al. Reference Brady, Scott, Neff and Glascock1997, Reference Brady, Cobb, Garza, Espinosa, Burnett, Brady and Prufer2005), the best-known Usumacinta example of which is the carved stalactite at Yaxchilan known as Stela 31 (Helmke Reference Helmke2017). Another possibility is that the sculpted cylinders were skeuomorphs evoking wooden columns that once stood in Maya buildings or even natural trees, to judge from a reference at Xcalumkin to columnar stone roof supports as te' (“wood; tree”; Graham and von Euw Reference Graham and von Euw1992:173; see also Doyle and Houston Reference Doyle and Houston2014:141, n1). Regardless of the columnar form's conceptual origin, however, Lacanjá Tzeltal remains regionally unique in its strong emphasis on column production. This feature would have been immediately apparent to any visitor familiar with the monumental traditional of western Maya courts.

“Squat” Monuments

We introduced the category “Miscellaneous Sculpted Stone” (MSS) for Lacanjá Tzeltal to account for unusually shaped sculptures that do not fit easily into pre-existing classifications. The most confounding members of the group are a series of short, thick monuments that have been designated as MSS 3–11 (Table 6). To account for possible distinctions among them without establishing a definitive classification or impeding future comparison with other Maya sculptures, we identify this MSS subclass as “squat monuments” to highlight their dense, blocky form.

Table 6. “Squat monuments” at Lacanjá Tzeltal.

The squat monuments are generally as wide as many of the site's stelae (Table 6). However, unlike the narrow and tall stelae, the squat monuments' length is not much greater than their width. Even those that are more rectangular than square, like MSS 3–7, are much lower and stouter than Lacanjá Tzeltal's stelae (Figure 11). Their bulky forms also contrast with the Lausanne Stela or miniature stelae from the northern lowlands, which preserve the proportions typical of Maya stelae, just at a reduced scale (compare Miller and Martin Reference Miller and Martin2004:191; Zender Reference Zender and Reents-Budet2012). The squat monuments are notably thicker than most quadrilateral Maya sculptures, their breadth and width being roughly equal (Table 6). As a result, their footprint is more square in shape, in contrast with the rectilinear footprint of typical Classic Maya stelae, panels, or lintels.

Figure 11. Miscellaneous Sculpted Stone 7, whose eroded central image shows a standing figure holding a horizontal ceremonial bar. Photograph by Matsumoto.

The iconography on MSS 7 suggests that at least some squat monuments were displayed vertically like stelae (Figure 11). Nonetheless, only MSS 8 appears to be in situ, complicating interpretation of their intended function. Some squat monuments may have supported other monuments or structures, functionally comparable to the burdened Atlantean figures shown on the central tablet in Palenque's Temple of the Sun or on Lintel 1 from Laxtunich (Houston et al. Reference Houston, Doyle, Stuart and Taube2017; Robertson Reference Robertson1991:95). But anything they sustained likely would have been perishable, as no stone candidates have been found (cf. e.g., Scott Reference Scott1978:30–45). Another possibility is that the squat monuments at Lacanjá Tzeltal served as altars, similar to the thick, rectilinear monuments identified at lowland Maya sites such as Chac II and Zacpetén (Pugh Reference Pugh2003:420; Smyth and Rogart Reference Smyth and Rogart2004:36), as well as in Central Mexico (e.g., Pohl Reference Pohl1998). Nonetheless, the squat monuments do not bear concentrated scorch marks as we might expect of altars on which burnt offerings were placed directly (compare, e.g., Palenque [Johnson Reference Johnson2018:86, Figure 28]; Altun Ha [Pendergast Reference Pendergast1982:110]; Piedras Negras [Satterthwaite Reference Satterthwaite, Weeks, Hill and Golden2005b (1933)]).

No other western Maya polity produced sculptures similar to the squat monuments, whose form is remarkably rare throughout the Maya area. The best morphological correlates are found in the Central Peten. La Naya Stela 4 (l. 83 cm, w. 64 cm, th. 40 cm), La Pochitoca Stela 1 (l. 156 cm, w. 73 cm, th. 49 cm), Tikal Stela 36 (l. 108 cm, w. 82 cm, th. 38 cm), and Yaxha Stela 4 (l. 187 cm, w. 126 cm, th. 66 cm), for example, all demonstrate similarly stocky proportions (Grube Reference Grube and Wurster1999:267–268; Jones and Satterthwaite Reference Jones and Satterthwaite1982:76; Mayer Reference Mayer1999:166). Most have been dated on stylistic grounds to the Preclassic or Early Classic period, although La Naya Stela 4 is probably a Late Classic creation (Grube Reference Grube and Wurster1999:253, 265; Grube and Martin Reference Grube and Martin2004:10; Jones and Satterthwaite Reference Jones and Satterthwaite1982:76; Mayer Reference Mayer1999:167). It is feasible that Lacanjá Tzeltal sculptors were influenced by the Central Peten tradition; as we discuss below, this parallel is among several that point to a non-local origin for the Sak Tz'i' court.

Central Ballcourt Marker

Of the altars at Lacanjá Tzeltal, only Altar 11 has been archaeologically excavated, as part of initial explorations in the ballcourt by Scherer and colleagues (Reference Scherer, Matsumoto, Schnell, Golden, Schroder, Scherer and Golden2019; Figure 12). At 97–105 cm in diameter and 14.5–18.0 cm in height, the Late Classic sculpture is the largest intact, rounded altar at the site. Although eroded, its carved upper surface preserves a scene of two figures shown in profile who face each other across a single column of three or four eroded glyph blocks (Figure 12). Kneeling with their arms bound behind their backs, they probably represent captives whose bent legs may be tied as well. They are immediately enclosed by abstracted, open centipede jaws representing the underworld and signaling the men's fate as sacrificial offerings (Taube Reference Taube, Ruiz, Sosa and Ponce de León2003:413–416, Figure 6). An intermediate ring embellished with 21 indented dots encircles the scene immediately outside the centipede maw, in an arrangement resembling the lunar disk with solar elements that rings the seated figure on an unprovenanced altar at the North Carolina Museum of Art (object no. 82.14).

Figure 12. The carved upper surface of Lacanjá Tzeltal Altar 11 showing two bound captives and ringed by a line of eroded hieroglyphs. Photograph by Scherer; photogrammetric model by Golden.

Finally, a horizontal row of 24 glyph blocks marks the outer limit of the carved surface. Unfortunately, all hieroglyphs are eroded except for the numerical prefixes and day sign cartouche of an illegible Calendar Round date (4 [tzolk'in] 2 [haab]; Figure 12). Further excavations directly below the altar revealed a cache with partial obsidian blades, chert fragments, bits of spondylus shell, and small greenstone pieces, all arranged around a chert spear point—the latter deposited under the monument so that it directly aligned with the column of glyphs between the kneeling captives. As pointed out by an anonymous reviewer, obsidian in particular has been found in other caches below ballcourt markers or altars in the western area, including a symbolically significant set of nine blades found under ballcourt monuments at Tonina, Chiapas and Quen Santo, Huehuetenango (Becquelin and Baudez Reference Becquelin and Baudez1979:79–87; Fox Reference Fox1996:485; Wölfel and Hernández Reference Wölfel and Hernández2017:86–87). However, the extent to which this represents a regional rather than a generally Classic Maya trend remains to be determined (e.g., Fox Reference Fox1996:485). Most obsidian recovered from the sub-Altar 11 cache represented debitage, and neither the two blades nor the chert point demonstrated clear evidence of human or animal protein when subjected to residue analysis (Roche Recinos Reference Roche Recinos2021:232–233).

Ball court altars at western Maya centers such as Piedras Negras (Satterthwaite Reference Satterthwaite, Weeks, Hill and Golden2005a [1944]:Figure 8.1), Tenam Rosario (Agrinier Reference Agrinier, Ochoa and Lee1983:243), Tonina (Mathews Reference Mathews1983:6–7), or Yaxchilan (Morley Reference Morley1931:136–137) were positioned in sets of three along the central playing alley. Excavations at the ends of the Lacanjá Tzeltal ball court, however, failed to produce additional altars, indicating that Altar 11 was placed in isolation. Lacanjá Tzeltal's I-shaped ballcourt thus appears to follow the pattern attested at nearby Plan de Ayutla, where a single column demarcated the center of the playing field (Martos López Reference López, Alberto, Golden, Houston and Skidmore2009:Figure 4). Measuring 1.1 m in height and 52 cm in diameter (Martos López Reference López, Alberto, Golden, Houston and Skidmore2009:65), the uncarved Plan de Ayutla stone formally resembles the columnar stelae of Lacanjá Tzeltal. It was set in such a fashion, however, that only its circumferential top projected above the playing alley, whereby it superficially resembled a typical ball court altar.

CARVED SURFACES

Although many monuments at the site are now eroded, Stelae 1–8, 10, and 24 and MSS 3 and 7 preserve traces of what appears to have been a preferred motif at Lacanjá Tzeltal: a standing figure, in a frontal pose with both sandaled feet turned outward, wearing a headdress and holding a long object. Further details are now largely indiscernible due to erosion, but the persons on Stelae 1, 3, and 10 and MSS 7 clearly hold a ceremonial bar (Figures 11 and 13). Most monuments at the site demonstrate shallow to moderate relief carving, which was typical of stelae throughout much of the Maya lowlands but not in western kingdoms like Piedras Negras, where sculptors favored moderate to high relief, or Tonina, where most extant stelae were carved in the round. An exception at Lacanjá Tzeltal is Stela 1, whose high-relief figure is particularly notable for its sculptured head that extends out up to 15 cm from the background (Figure 14). None of the Lacanjá Tzeltal stelae retains legible glyphs with identifying information about the standing figures, but their appearance on multiple publicly displayed monuments suggests that they represented local rulers who either commissioned the sculptures or were ancestors of those who did (cf. Stuart Reference Stuart1996).

Figure 13. Lower fragment of Stela 3 showing a standing figure holding a diagonally positioned ceremonial bar. Photograph and photogrammetric model by Matsumoto.

Figure 14. Upper fragment of Lacanjá Tzeltal Stela 1 showing eroded sculptured head. Photograph by Matsumoto.

A low-relief carving of an upright ruler with a ceremonial bar is perhaps the most common conservative motif in Classic Maya royal sculpture and is especially characteristic of stelae (see Proskouriakoff Reference Proskouriakoff1950:88–89). Yet it is rare among western Maya polities, where stelae iconography is notably diverse and sculptors explored greater depth of relief (Miller Reference Miller and Houston1998; O'Neil Reference O'Neil2012). The ceremonial bar was rarely depicted at western courts, and then more often with minor political figures than with the king. The bar is absent from monuments at Piedras Negras (Proskouriakoff Reference Proskouriakoff1950:89), where stelae instead depict lords seated on scaffolds, holding spears, and receiving captives or scattering from pouches. At Yaxchilan most stelae show lords receiving captives, dancing, or scattering; sculptors there, as well as at nearby Bonampak and Lacanha, also favored profile views of their protagonists, even if their legs faced outward (Proskouriakoff Reference Proskouriakoff1950:22). Some stelae at Tonina and the one stela at Palenque show lords clutching ceremonial bars (see Graham and Mathews Reference Graham and Mathews1996; Graham et al. Reference Graham, Stuart, Mathews and Henderson2006; Miller Reference Miller and Trejo2000:181), but they were all carved in the round similar to the stelae of Copan (McHargue Reference McHargue1995; Proskouriakoff Reference Proskouriakoff1950). In contrast, the bas-relief representation of a standing figure with a ceremonial bar at Lacanjá Tzeltal, which may be echoed on a fragmented stela at neighboring El Palma (Velázquez Valadez Reference Velázquez Valadez, García-Bárcena, Moll, Cossío, Santamaría and Valadez1986:Figure 6), recalls sculptural traditions in the central lowlands, where such staid conventions predominated throughout the Classic period.

In other regards, however, the artisans at Lacanjá Tzeltal drew iconographic inspiration from their western neighbors. Late Classic monuments at Piedras Negras, such as Stelae 1, 3, 6–9, and 25–26 (see Maler Reference Maler1901), are reminiscent of Lacanjá Tzeltal Stela 1 in their high-relief, frontal representations of rulers with ceremonial bars (compare Miller Reference Miller and Houston1998:208). But other Lacanjá Tzeltal stelae with more complex scenes strongly resemble monumental imagery at western Maya courts as well. Stela 15 portrays at least two figures standing in two separate registers (Golden et al. Reference Golden, Scherer, Houston, Schroder, Morell-Hart, Álvarez, Van Kollias, Talavera, Matsumoto, Dobereiner and Firpi2020:75; Ramiro Talavera and Kollias Reference Ramiro Talavera, Van III Kollias, Scherer and Golden2018:Figures 9.8–9.9). Stacked iconographic registers are rare in Maya sculpture but do appear on Stelae 1 and 2 from La Mar (Maler Reference Maler1903:Plate XXXVI), a frequent antagonist of Sak Tz'i'. The fragmentary Stela 14, in turn, shows the torso of a figure in profile, probably a courtier based on his relatively kempt appearance, kneeling before a standing person now visible only as a partial torso and extended right arm (Figure 15). Regionally, this theme is closely associated with Palenque but also resembles broader compositional emphases on a standing ruler flanked by kneeling subordinates found at Yaxchilan and Piedras Negras. Such monumental scenes at the latter sites, however, tend to appear more static (compare Schele and Mathews Reference Schele and Mathews1979:Nos. 141–142; Stone Reference Stone, Diehl and Berlo1989:162–163; Stuart Reference Stuart2005b:Figure 4). Similarly, the incomplete Stela 12 at Lacanjá Tzeltal shows the lower bodies of two kneeling captives or supplicants, one grasping feathers, whose soles face the viewers (Golden et al. Reference Golden, Scherer, Houston, Schroder, Morell-Hart, Álvarez, Van Kollias, Talavera, Matsumoto, Dobereiner and Firpi2020:Figure 7), a highly unusual pose also found on the Temple XIX stucco pier at Palenque (Stuart Reference Stuart2005b:Figure 4). The missing upper portion of Stela 12 once depicted an authority figure, presumably seated on a throne (Golden et al. Reference Golden, Scherer, Houston, Schroder, Morell-Hart, Álvarez, Van Kollias, Talavera, Matsumoto, Dobereiner and Firpi2020:75, Figure 7). Similar scenes of elevated lords presiding over genuflecting subordinates are found elsewhere in the Usumacinta River area, including at Piedras Negras, La Mar, Yaxchilan, and Palenque (Miller and Brittenham Reference Miller and Brittenham2013:154–158; Miller and Martin Reference Miller and Martin2004:Figure 52; Scherer and Golden Reference Scherer, Golden, Scherer and Verano2014).

Figure 15. Lacanjá Tzeltal Stela 14 showing a man, probably a courtier, kneeling before a standing figure. 3D model by Golden.

Another notable factor in visual and monumental culture at Lacanjá Tzeltal is stela height. Although only Stelae 3, 4, 7, 11, 17, 21, and 22 seem to preserve their original vertical measurements, they and the surviving partial stelae at Lacanjá Tzeltal that are over 2 m tall suggest two general groupings according to height. One set (Stelae 1–4, 9, 12, 15, 21, 22) reached a minimum of 212 cm and sometimes exceeded 250 cm. The tallest complete stela, Stela 3, stood at 244 cm, but was probably surpassed by the now fragmentary Stelae 1, 2, and 9, which in their current states reach between 237 and 256 cm tall. The base or top of over one dozen other stelae at the site are now incomplete, too, but they originally may have reached similar heights. The other, shorter group comprised monuments such as Stelae 7, 11, and 17 that ranged between approximately 150 and 175 cm in height.

Many stelae at Yaxchilan, including the 150 cm tall Early Classic Stela 27 (Tate Reference Tate1992:261), would have fit comfortably into the shorter group at Lacanjá Tzeltal, although some, like the eighth-century Stelae 1, 4, and 11 and the seventh-century Stela 19, reached at least 400 cm in height (see Tate Reference Tate1992:162–264). Starker contrasts are apparent with Piedras Negras, however, where almost all known, complete stelae stand over 225 cm tall and more than a dozen over 400 cm (Stuart and Graham Reference Stuart and Graham2003; Teufel Reference Teufel2004:377–470). There, one observes a general trend toward increasing stela height, with the Early Classic Stelae 30 and 42 both under 300 cm and four of the tallest five, Stelae 17, 19, 23, and 40, ranging from 437 to 485 cm, being late eighth-century products (see Mathews Reference Mathews, Willey and Mathews1985:Table 1; Morley Reference Morley1938:47; Teufel Reference Teufel2004:377–470). Thus, even if the Lacanjá Tzeltal stelae demonstrated a comparable increase in height over time—a scenario that cannot be confirmed on present evidence—they remained well below the average for stelae at the two neighboring dynastic powers.

Overall, Lacanjá Tzeltal Stelae 12, 14, and 15 and Panel 1 feature more dynamic, complex representations than Stelae 1–8, 10, and 24 and MSS 3 and 7. Proskouriakoff (Reference Proskouriakoff1950:23) first observed an iconographic transition among Late Classic Maya monuments from frontal and more static to profile and more dynamic human representation, and Miller (Reference Miller, Jeremy A. and Henderson1989) argues that this and other modes of iconographic conservatism were persistent even in later monuments produced by sculptors at the Central Peten hegemon Tikal. As such, the latter, relatively conservative group of bas-relief monuments, each of which displays a standing figure facing forward with a ceremonial bar, may represent a cultural, if not also a chronological shift among Lacanjá Tzeltal sculptors. Their architectural distribution—namely, the clustering of Stelae 1–7 in front of Str. E5-13 and of Stelae 12 and 15 in front of Str. E4-1 (Figure 3)—could thus reflect parallel shifts in spatial emphasis for monument dedication. We wonder, too, if such changes in sculptural representation reflect a court that originated from the central lowlands but whose artisans increasingly engaged with western traditions after its relocation, emulating specific themes and conventions as well as an overall diversification and innovation of sculptural forms, including taller stelae. In the absence of secure dates, however, the hypothesized timeline remains untested for now.

PALEOGRAPHY

Among the monuments on site at Lacanjá Tzeltal, traces of hieroglyphic inscriptions are only evident on Stelae 2–7, 10, 11, 14, 16, and 24. Of these, just three contain legible signs, all calendrical. Scherer et al. (Reference Scherer, Golden, Schroder, Dobereiner, Whittaker, Golden and Scherer2015:21) identified a legible period-ending of 9.8.0.0.0 (August 23, 593) on Stela 11 that possibly marked its dedication date, but the moment has since been buried under rubble from a looter's trench on the east side of Str. E5-7 and could not be redocumented in subsequent investigations. Consequently, our paleographic analysis relies on Panel 1 (Figure 2). Multiple discrepancies are apparent between Panel 1 and the other Sak Tz'i' inscriptions, but several are especially salient in political and cultural context. For example, the title “lord of Ak'e'” (Ak'e' ajaw) is enhanced with the prefix k'uhul on every Sak Tz'i' monument, including Lacanjá Tzeltal Panel 1, except for the Brussels Panel (compare, e.g., Dumbarton Oaks Panel 1 from Lacanha, Stuart Reference Stuart2007:42). Comparison with nearby Piedras Negras and Yaxchilan indicates that scribes tended to be locally consistent in whether they wrote k'uhul in another polity's emblem glyph (Matsumoto Reference Matsumoto2021:250), suggesting either that the Denver and Brussels Panels represent an earlier stage of the scribal tradition that produced the other Sak Tz'i' inscriptions, or that they perhaps originated from a different scribal community altogether.

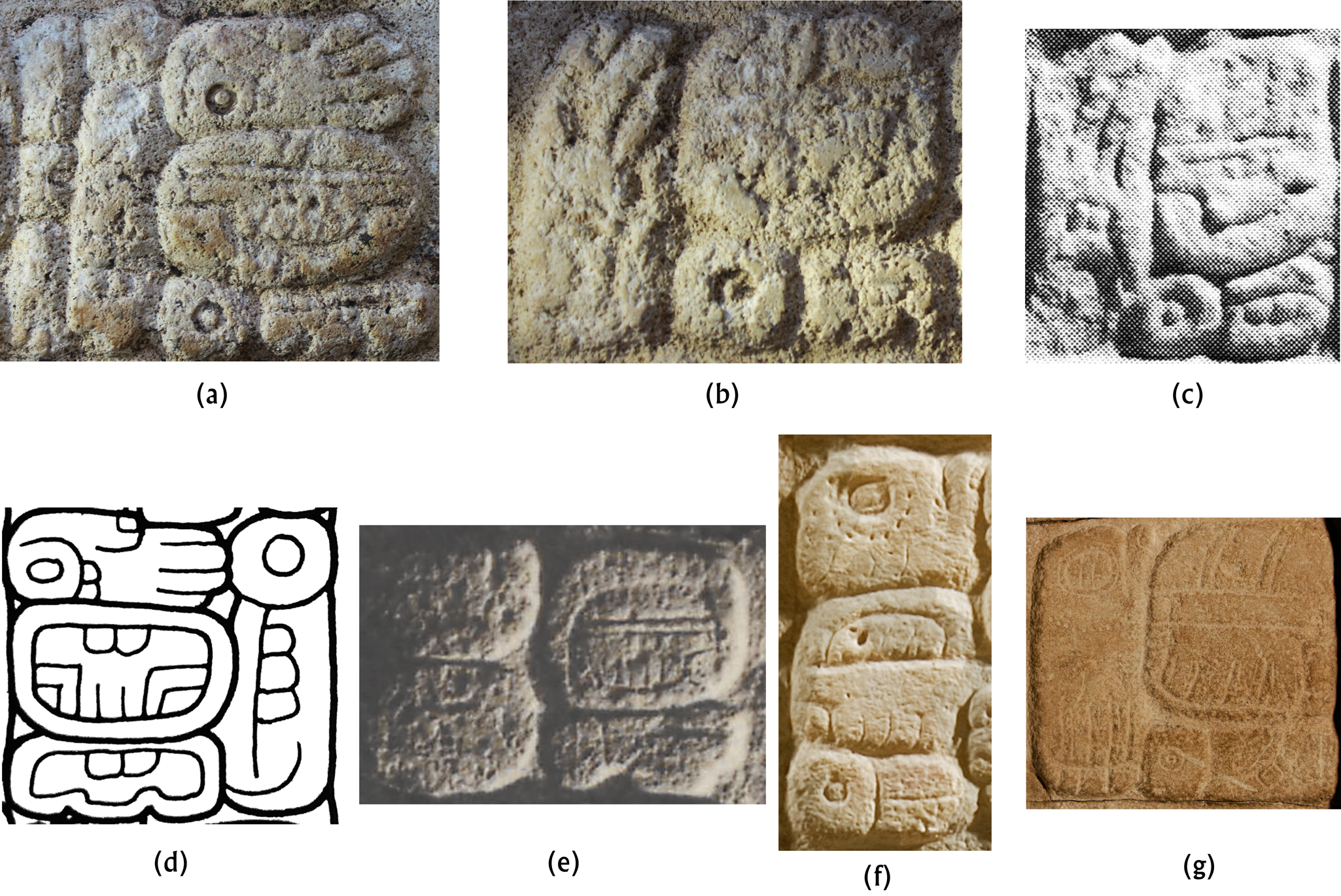

A more significant divergence affects spellings of K'ab Kante', the name of at least two separate Sak Tz'i' lords (see Golden et al. Reference Golden, Scherer, Houston, Schroder, Morell-Hart, Álvarez, Van Kollias, Talavera, Matsumoto, Dobereiner and Firpi2020). All spellings on Panel 1 deploy the logograph T1531st K'AB (Figures 16a and 16b), as on the unprovenanced Nuevo Jalisco Panel (Bíró Reference Bíró2011:Figures 162a and 162b), the Lausanne Stela, and the Caracas Panel—the latter albeit in reference to an individual described as the “divine lord of Ak'e'” (Figures 16c and 16d). (All Maya hieroglyphs are referenced according to the current glyph catalog of the Textdatenbank und Wörterbuch des Klassischen Maya project; Prager and Gronemeyer Reference Prager, Gronemeyer, Gülden, van der Moezel and Elsbergen2018.) In contrast, the first component of the name K'ab Kante' is written syllabically as k'a[ba] (T0669st [T0501st]) on the Brussels and Denver Panels, as well as on Piedras Negras Stela 26 (Figures 16e–16g). Within a given polity, logographic spellings of local rulers’ names are sometimes accompanied by phonetic complements but are rarely replaced with syllables only (though cf. ahk “turtle” in dynastic names at Piedras Negras, Matsumoto Reference Matsumoto2021:Tables 4.2, 4.5). A prominent dynastic name whose orthography in monumental inscriptions varied precisely along these lines is Waxaklajuun Ubaah K'awiil. At Copan, the second component of the local Late Classic king's name is consistently written logographically with T0757st BAAH. Elsewhere, however, the name is often (under-)spelled with just T0501st ba, both in foreign references to the Copan ruler (Looper Reference Looper2001:Figures 2, 4, 22; Tsukamoto and Esparza Olguín Reference Tsukamoto, Olguín, Houston, Skidmore and Golden2015:Figures 6, 12) and in citing a local dynast with the same name, as at Naranjo, Peten (Graham Reference Graham1978:86). Because dynastic names were not only politically meaningful but also frequent components of monumental texts, deviations from typical orthography would have been “marked” in a semiotic sense (Battistella Reference Battistella1996; Jakobson Reference Jakobson1984:1–12), salient precisely because they contrasted with what local scribes and readers perceived as the norm.

Figure 16. Spellings of the name K'ab Kante' using (a–d) the logograph K'AB or (e–g) syllabic k'a-b'a, on (a–b) Lacanjá Tzeltal Panel 1 (a.d. 775); (c) Caracas Panel (a.d. 754); (d) Lausanne Stela (a.d. 864); (e) Piedras Negras Stela 26 (a.d. 628); (f) Brussels Panel (a.d. 693); (g) Denver Panel (a.d. 693). Images (a–b) by Jeffrey Dobereiner and Whittaker Schroder; (c) courtesy of Sotheby's; (d) by Simon Martin; (e) by Teobert Maler, Ibero-Amerikanisches Institut; (f) © RMAH, Brussels; (g) © Denver Museum of Nature & Science.

Despite their differences, a shared Sak Tz'i' affiliation of Lacanjá Tzeltal Panel 1 and the unprovenanced monuments is supported by their exclusive preference for the dog-head logograph T0752st TZ'I' in the title Sak Tz'i' ajaw (Figures 2 and 4). Some inscriptions at other sites, in contrast, represented tz'i' syllabically (El Cayo Panel 1, Maler Reference Maler1903:Plate XXXV; Piedras Negras Stela 26, Maler Reference Maler1901:Plate XXXIII; compare Houston cited in Anaya Hernández et al. Reference Anaya Hernández, Guenter and Zender2003:Figure 2; Stuart Reference Stuart1987:10). Parallel tendencies for foreign emblem glyphs to include more phonetic specificity are found in references at La Amelia to the Mut polity emblem glyph of Dos Pilas and Aguateca, to which the phonetic complement mu was prefixed. Likewise, the name of Yaxchilan king Yaxun Bahlam IV's foreign wife, Ix Mut Bahlam from Zapote Bobal (Martin and Grube Reference Martin and Grube2000:131), is spelled on that site's Lintel 17 with a rare postposed phonetic complement (MUT-tu, Stuart Reference Stuart1993). Her title Ix Hix Witz Ajaw, too, is represented there and on Lintel 43 with a wi-tzi sequence that is atypical of the Zapote Bobal emblem. Thus, the phonetically explicit version of tz'i' suggests a weaker attachment to T0752st TZ'I', whose canine form was probably considered iconic of the Sak Tz'i' polity. Consequently, scribes who identified with the “White Dog” polity purposefully would have deployed the emblematic logograph, whereas only foreign scribes would have spelled tz'i' syllabically.

Among the unprovenanced inscriptions attributed to the Sak Tz'i' polity, then, the position of Lacanjá Tzeltal Panel 1 remains equivocal. The Caracas Panel, despite being badly recarved, demonstrates the most paleographic similarity but is also the closest to Panel 1 chronologically (Figure 17; Table 2). The Stendahl Panel and Lausanne Stela are more difficult to situate, given their greater temporal distance from Panel 1's dedication and palpably distinct hands (Mayer Reference Mayer1987:Plate 33; Miller and Martin Reference Miller and Martin2004:Plate 107). The current evidence thus does not clearly indicate whether the unprovenanced Sak Tz'i' inscriptions were composed at Lacanjá Tzeltal. Zooming out to consider the broader regional context, however, we can nonetheless begin to contextualize Lacanjá Tzeltal's scribal tradition within the western region. There are several paleographic clues that the scribes of Panel 1 engaged with communities to the north, especially Palenque and Piedras Negras, a pattern that accords well with our earlier observations regarding parallels in sculptural form and content of imagery.

Figure 17. Caracas Panel, the unprovenanced Sak Tz'i' monument demonstrating the greatest paleographic similarity to Lacanjá Tzeltal Panel 1. Photograph courtesy of Sotheby's.

One rare hieroglyph on Panel 1 is a variant of T0088st ji with a stripe along the central vertical axis (Figure 18a). It is not unprecedented in the Maya corpus but was much more frequent in the Central Peten (Figures 18b and 18c). The closest western analogues are found on Late Classic monuments at El Cayo, a subsidiary of Piedras Negras (Chinchilla Mazariegos and Houston Reference Chinchilla Mazariegos, Houston, Laporte, Escobedo, Villagrán and de Brady1993), and the more distant Palenque, including the unprovenanced Dumbarton Oaks Panel 2 that has been attributed to the latter kingdom (Figures 18d and 18e). Interestingly, the striped T0088st variant is even attested as far south as Quirigua (Figure 18f). Another salient form on Panel 1 is a conflation of the head variant T1521st ji with T0526st KAB in the phrase u-kabijiiy (“the doing of; the tending of”; Figure 19a; Stuart Reference Stuart and Scarborough2005a:283–284, Reference Stuart2011:2–3). Scarce in the Classic Maya corpus generally, occurrences in the western region are known at Bonampak and Piedras Negras but are overwhelmingly concentrated at Palenque, where scribes created at least nine examples on monuments dedicated between the mid-seventh and late eighth centuries (Figures 19b–19d). The combination is somewhat more widespread in the Central and Eastern Peten, but the only other lowland site with a half-dozen or more uses in monumental inscriptions seems to have been Quirigua (Figures 19e–19h). These details hint at the wide-ranging networks of exchange into which Lacanjá Tzeltal's scribes were integrated, however indirect their ties to more distant polities may have been.

Figure 18. Unusual variant of T0088st ji with a vertical stripe down the middle on (a) Lacanjá Tzeltal Panel 1 (A.D. 775). Image by Jeffrey Dobereiner and Whittaker Schroder; (b) La Corona Panel 1 (A.D. 677). Image by Matsumoto, courtesy of the Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología de Guatemala; (c) Uxul Stela 13 (A.D. 662). Image by Proyecto Arqueológico Uxul; (d) El Cayo Altar 4 (A.D. 731). Image by by Matsumoto, from Montgomery Reference Montgomery1995:Figure 51; (e) Palenque Tablet of the Scribe (early/mid-eighth century A.D.). Gift of the Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1958. © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University, 58-34-20/53743 (detail); (f) Dumbarton Oaks Panel 2 (early eighth century A.D.). Image by Matsumoto, © Dumbarton Oaks, Pre-Columbian Collection, Washington, DC; (g) Quirigua Stela F (A.D. 761). Gift of the Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1958. © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University, 58-34-20/73898 (detail).

Figure 19. T1521st ji conflated with T0526st KAB in the phrase u-kabijiiy (“the doing of; the tending of”) on (a) Lacanjá Tzeltal Panel 1 (A.D. 775). Image by Jeffrey Dobereiner and Whittaker Schroder; (b) Bonampak Sculptured Stone 5 (A.D. 752). Gift of Ian Graham, 2004. © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University, 2004.15.1.7128.1 (detail); (c) Piedras Negras Panel 3 (A.D. 782). Image by Matsumoto; (d) Palenque Tablet of the 96 Glyphs (A.D. 783). Gift of Ian Graham, 2004. © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University, 2004.15.1.1769.2 (detail); (e) Step VI of Naranjo Hieroglyphic Stairway 1 from Caracol (A.D. 642). Image by Teobert Maler, Ibero-Amerikanisches Institut; (f) La Corona Panel 1 (A.D. 677). Image by Matsumoto; (g) Uxul Stela 17 (Late Classic). Image by Nikolai Grube, Proyecto Arqueológico Uxul; (h) Quirigua Stela C (A.D. 775). Gift of the Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1958. © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University, 58-34-20/73894 (detail).

The major Palenque inscription that is temporally closest to Lacanjá Tzeltal Panel 1 is the Tablet of the 96 Glyphs from a.d. 783 (Miller and Martin Reference Miller and Martin2004:Figure 71). Its concentration of calligraphically and hieroglyphically unique signs is unparalleled in the history of Maya writing but nonetheless includes intriguing correspondences with Panel 1. In addition to several uses of T0011st u, for example, the Tablet of the 96 Glyphs shares with Panel 1 several T0679st i variants with dots above the base, large-nosed and large-lipped human head variants, X-shaped number fillers, and a strikingly similar [KAB]ji conflation (Figure 19d). Moreover, most of these traits are uncommon elsewhere in the western area (compare Matsumoto Reference Matsumoto2021:Figure 8.17b, Table 17.12), reinforcing the likelihood that Palenque scribes exercised significant influence on their peers at late eighth-century Lacanjá Tzeltal.

Supporting these paleographic similarities are additional correspondences in iconographic and narrative content between Lacanjá Tzeltal Panel 1 and monuments at Palenque. The scene on Panel 1 of K'ab K'ante' brandishing a weapon over a now-missing subordinate aligns with the western Maya tradition of emphasizing scenes of captive-taking and presentation in monumental iconography (Figure 2; Miller Reference Miller and Houston1998; Proskouriakoff Reference Proskouriakoff1950:5). Yet even more notably, it demonstrates parallels with the Palenque-area panel at Dumbarton Oaks (see Houston and Taube Reference Houston, Taube, Pillsbury, Doutriaux, Ishihara-Brito and Tokovinine2012), in that the local ruler is shown dancing in the guise of the rain god Chahk, with his characteristic axe and manopla in hand. Similarly, the Lacanjá Tzeltal inscription memorializes a royal death and subsequent mortuary rites much in the same spirit as the funerary panels found at Piedras Negras and its allied centers, including El Cayo and the locale featured on the unprovenanced K'an Xook Panel, as well as on the Stendahl Panel (Golden et al. Reference Golden, Scherer, Houston, Schroder, Morell-Hart, Álvarez, Van Kollias, Talavera, Matsumoto, Dobereiner and Firpi2020; Tokovinine Reference Tokovinine, Rivera and Fort2006). In addition, the opening passage on Panel 1 includes a lengthy discussion of primordial times akin to the content of panels at Palenque but unusual in regional context (see Golden et al. Reference Golden, Scherer, Houston, Schroder, Morell-Hart, Álvarez, Van Kollias, Talavera, Matsumoto, Dobereiner and Firpi2020:78–79).

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

The identification of Lacanjá Tzeltal and its connection with the Sak Tz'i' polity represented a major breakthrough in Classic Maya studies, permitting scholars to finally tie the known epigraphic entity to a physical site and its archaeological history (Golden et al. Reference Golden, Scherer, Houston, Schroder, Morell-Hart, Álvarez, Van Kollias, Talavera, Matsumoto, Dobereiner and Firpi2020). Yet as so often happens, many of the development's promises remain tantalizingly out of reach. Archaeological excavations at Lacanjá Tzeltal have yet to recover an in situ inscription with an emblem glyph or other unequivocal evidence of the polity's presence. Moreover, our understanding of the Late Classic occupation remains limited. One unexpected finding from initial investigations is that much monumental architecture at the site represents one or two phases of Late Classic construction overlaying a significant Late Preclassic (400 b.c.–a.d. 200) settlement established before the advent of hieroglyphic writing (Golden et al. Reference Golden, Scherer, Houston, Schroder, Morell-Hart, Álvarez, Van Kollias, Talavera, Matsumoto, Dobereiner and Firpi2020:73, 81; compare Saturno et al. Reference Saturno, Stuart and Beltrán2006). Future excavations will help us determine whether local settlement stretches at least as far back as the early seventh century, corresponding with the earliest historic mention of Sak Tz'i' on Piedras Negras Stela 26. Until then, however, the relatively shallow Classic-era occupation requires us to consider that Lacanjá Tzeltal may not have been the only Sak Tz'i' capital.

Paleographic and archaeological research offers similarly ambiguous conclusions. Lacanjá Tzeltal's on-site corpus of stone sculpture is uniquely robust for a site governed by an ajaw rather than a more elevated k'uhul ajaw. Most monuments appear never to have been carved with iconography or hieroglyphs, and the few that were have since been badly damaged by human and natural intervention. Nonetheless, Panel 1 contains enough hieroglyphs to draw some insights into the monument's position within the Sak Tz'i' polity and the involvement of Lacanjá Tzeltal's scribes and sculptors in regional networks of hieroglyphic exchange. Indeed, their position is especially interesting in the context of the political history of Sak Tz'i'. Notable here is the lack of significant sculptural correspondences with monuments at prominent southern neighbors Bonampak or Yaxchilan. Panel 1 was dedicated during an interval of increasing confrontation with Yaxchilan, which eventually culminated in the defeat of Sak Tz'i' lord Yete' K'inich at the hands of a Yaxchilan-Bonampak alliance (Anaya Hernández et al. Reference Anaya Hernández, Guenter and Zender2003:187; Golden et al. Reference Golden, Scherer, Houston, Schroder, Morell-Hart, Álvarez, Van Kollias, Talavera, Matsumoto, Dobereiner and Firpi2020:79, Table 1; Mathews Reference Mathews and Robertson1980). That Lacanjá Tzeltal scribes would have been disinclined to engage with Yaxchilan during this interval is reasonable and may point to further tensions that escape mention in the known epigraphic record. Clearly, Lacanjá Tzeltal was politically removed enough from Yaxchilan's orbit to resist any imposition on its local cultural tradition, unlike Yaxchilan's subsidiary sites (Golden et al. Reference Golden, Scherer, René Muñoz and Vasquez2008:253, 263). Scribal connections between Lacanjá Tzeltal and Tonina, conversely, may have comprised part of the broader interactions of Sak Tz'i' with Tonina, leading up to the latter's capture of a later Sak Tz'i' ruler, Jats' Tokal Ek' Hix, at the end of the eighth century (Anaya Hernández Reference Anaya Hernández2001:71–72; Bíró Reference Bíró2005:26–27; Golden et al. Reference Golden, Scherer, Houston, Schroder, Morell-Hart, Álvarez, Van Kollias, Talavera, Matsumoto, Dobereiner and Firpi2020:Table 1; Martin and Grube Reference Martin and Grube2000:188–189).

The affiliation with Palenque is the most compelling sculpturally but perhaps the most surprising epigraphically. Piedras Negras Stela 26 memorializes the taking of a captive from Sak Tz'i' alongside another from Palenque and thus implies that they were allied in conflict against their common, victorious enemy in 628 (Anaya Hernández et al. Reference Anaya Hernández, Guenter and Zender2003:186; Bíró Reference Bíró2005:2, 31). This initial epigraphic reference to Sak Tz'i' is, to our knowledge, the only one that includes Palenque—at almost 100 km distant the major western center most geographically removed from Lacanjá Tzeltal. Nonetheless, current understanding of Classic Maya geopolitics makes it historically reasonable to posit that the cultural exchange with Palenque evident in Lacanjá Tzeltal's sculptures represented an extension of the political alliance memorialized several generations earlier at Piedras Negras. Like Sak Tz'i', Palenque remained at odds with Piedras Negras for most of its subsequent recorded history: during the late seventh century, the two kingdoms jostled for control over Santa Elena, a small but strategically located settlement in eastern Tabasco (Martin Reference Martin2020:263–268), and a Palenque sajal or local noble captured a Piedras Negras sajal in the early eighth century (Martin and Grube Reference Martin and Grube2000:173).

Importantly, too, Palenque's broader military activity in the late seventh century extended its influence southward over La Mar and Anaite, based on references at Tonina to captives from those sites who are tagged as vassals of Palenque's king (Martin Reference Martin2020:271–272; Martin and Grube Reference Martin and Grube2000:170, 181–182). No epigraphic record survives of interaction between Palenque and Sak Tz'i' during this period, but circumstantial evidence supports the idea that both Lacanjá Tzeltal and La Mar would have been convenient allies for Palenque in its recurring conflicts with Tonina; the most easily traversed route from Palenque led southward past La Mar and Lacanjá Tzeltal before turning westward to go up into the highlands to Tonina (Martin and Grube Reference Martin and Grube2000:181). Nearby La Mar may have offered Lacanjá Tzeltal an additional source of Palenque-based influence, too, considering its political connections to the northern overlord and similarities in the tiered arrangement of stela iconography.

In addition, contact with Lacanjá Tzeltal artisans would have been supported by Palenque's economic engagement with Maya polities farther south, such as Cancuen. Workshops at that site were a likely source for at least some of the jade used in K'inich Janaab' Pakal's funerary mask (Kovacevich et al. Reference Kovacevich, Neff, Bishop, Neff and Speakman2005; Neff et al. Reference Neff, Kovacevich, Bishop and Nadal2010:134–135), even if later production stages were realized locally at Palenque (Melgar Tísoc et al. Reference Melgar Tísoc, Ciriaco, Nadal, Castro and Lowe2013:153–156). Excavations at Cancuen have recovered Chablekal Fine Gray wares believed to have been imported from Palenque (Kovacevich Reference Kovacevich, Hirth and Pillsbury2013:265, 268–269). Comparison of monumental iconography and hieroglyphs additionally points to substantial interchange between elite artisans at Palenque and Copan even farther south (Matsumoto Reference Matsumoto2021:460–465; Proskouriakoff Reference Proskouriakoff1950:116–117, 121–122; Riese Reference Riese, Boone and Willey1988). One Copan inscription may even document the marriage of a woman from Palenque's royal family into the local dynasty (Marcus Reference Marcus1976:145; Martin Reference Martin2020:184, n19; Riese Reference Riese, Boone and Willey1988:181–186). Merchants, royal entourages, and others traversing the route from Copan or Cancuen up to Palenque would have passed by and likely through Sak Tz'i' territory (see Martin Reference Martin2020:184, 306), bringing with them knowledge of cultural practices that they encountered along the way (compare Demarest et al. Reference Demarest, Andrieu, Torres, Forné, Barrientos and Wolf2014:Figure 1).