Mental health law permits and regulates the non-consensual treatment of mental disorders. This stream of law has typically focused on the status of the individual as a person with mental disorder. If the presence and severity of mental disorder are established formally, non-consensual treatment decisions may be justified, principally to reduce risk. The abilities needed for patients to decide for themselves about treatment have therefore tended to receive limited attention. Reference Hale1 A parallel stream of law has evolved aimed at safeguarding the freedom of individuals from battery or assault in a medical or surgical context. Inherent to this has been a concept of decision-making capacity or competence (DMC) as one of the necessary conditions for consent to be valid. The terms ‘capacity’ and ‘competence’ have overlapping meanings (and are used differently in North America and the UK) and for the purposes of this paper we take them to be equivalent. Although the concepts within this stream of law are old, it was not until the late 20th century that courts in the USA and UK began to systematically probe the abilities needed to decide treatment for oneself. A focus was on the decision-making abilities required for autonomous treatment choice. Reference Berg, Appelbaum and Grisso2,3 Because of the different historical origins of these two streams of law it became natural to think that DMC law was for medical and surgical patients only, yet the concept of DMC has been applied increasingly to psychiatric patients. In the USA in the 1960s and 1970s libertarianism and the civil rights movement pressed states to recognise the right of psychiatric patients to refuse psychotropic drugs. Reference Appelbaum4 Attention was directed towards reconceptualising mental health law in terms of consent and DMC. Reference Stone5,Reference Roth6 In England, the Mental Capacity Act which came into effect in 2007 now applies to any adult patient: medical or psychiatric, in addition to extant mental health law.

Attempts to operationalise the abilities required to make competent treatment decisions led to Grisso and Appelbaum's influential four abilities model based on an analysis of US case law. Reference Berg, Appelbaum and Grisso2,Reference Appelbaum and Grisso7 This became the MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool - Treatment (MacCAT-T). The four abilities - understanding, appreciation, reasoning and expressing a choice - overlap with the English legal definition (understanding, retaining, using and weighing, and expressing a choice). Concerns have been expressed that the DMC test, as currently understood, is ill adapted to the distinctive features of psychiatric illness that may undermine DMC which, it is argued, are unlike those seen in medical illnesses such as delirium and dementia - being more related to values and less related to cognitive processes. Reference Tan, Hope, Widdershoven, McMillan, van der Scheer and Hope8,Reference Fulford9 The MacCAT-T is a semi-structured interview, probing: (a) understanding relevant information thereby engaging in the process of informed consent; (b) appreciating that the information is relevant to the patient's predicament, not distorting its reality; (c) reasoning with the information in the sense of being able to manipulate it logically; and (d) expressing a choice - at all or without severe ambivalence. The MacCAT-T is a semi-structured interview that involves prompts and probes as well as anchors for scoring each ability on a short scale. The tool does not give a total score and the abilities are considered distinct, nor is it designed to provide, by itself, a simple binary (pass/fail) capacity assessment.

Cognitive impairment occurring in, for example, dementia or intellectual disability may be reducible to measurable psychological constructs (such as attention, memory), dysfunction of which would be expected to have an impact most on understanding. However, the psychopathology that may compromise competence in psychiatric patients is likely to centre on the harder to operationalise ‘use or weigh’ or ‘appreciation’ abilities. Our aim therefore was to compare the underlying components of mental capacity in two populations - acutely ill medical and psychiatric patients - and to uncover which abilities were particularly having an impact on judgements of DMC among those patients able to express a choice.

Method

We made use of data from two previously reported, separate studies. One comprised consecutive admissions to the acute adult psychiatric wards of the Maudsley Hospital London Reference Owen, Szmuker, Richardson, David, Hayward and Rucker10-Reference Owen, Richardson, David, Szmukler, Hayward and Hotopf12 and the other consecutive admissions to the acute adult medical wards of King's College Hospital, London. Reference Raymont, Bingley, Buchanan, David, Hayward and Wessely13 The two hospitals are adjacent and serve broadly the same inner-city catchment of South East London, which is characterised by ethnic diversity and wide disparities of health and wealth. Reference Hatch, Frissa, Verdecchia, Stewart, Fear and Reichenberg14 The methods are reported in detail elsewhere. Reference Owen, Richardson, David, Szmukler, Hayward and Hotopf12,Reference Raymont, Bingley, Buchanan, David, Hayward and Wessely13 The Joint South London and Maudsley and the Institute of Psychiatry NHS Research Ethics Committee approved the study.

Measurement of DMC

In both samples a clinician with more than 3 years' training in psychiatry and membership of the Royal College of Psychiatrists assessed DMC. The DMC test is time- and decision-specific. Patients were seen within a week of admission. The relevant treatment decision was determined. In the psychiatric hospital this was either a medication decision (if the treating team were mainly recommending this to stabilise a mental state) or a decision to be in hospital (for example if the treating team were recommending admission as a means of reducing suicide risk). In the general hospital the treatment decision was the most recently used intervention to investigate or treat the main reason for admission (such as intravenous antibiotics or an endoscopy).

The researcher conducted a clinical interview and used the MacCAT-T to guide a binary capacity judgement based on the English legal definition of DMC. Measurement of DMC therefore took the form of MacCAT-T ability scores (continuous variables) and a DMC judgement (binary variable). The scales for appreciation and reasoning were comparable for the two samples, although the scale for understanding was shortened from 0-6 to 0-4 in the medical sample. This limitation was accepted because of practical constraints on obtaining and disclosing precise information about diagnosis in acute medical settings where patients were often undergoing diagnostic investigations. Reference Raymont, Bingley, Buchanan, David, Hayward and Wessely13

Previous research has shown that the interrater reliability of the four abilities is generally good. Reference Okai, Owen, McGuire, Singh, Churchill and Hotopf15 For each of the samples we conducted a reliability study wherein interviews were recorded and transcribed, and transcriptions rated by a panel of senior clinicians. These studies of binary DMC judgements yielded kappa values exceeding 0.8, indicating excellent reliability. Reference Raymont, Buchanan, David, Hayward, Wessely and Hotopf16,Reference Cairns, Maddock, Buchanan, David, Hayward and Richardson17

Analysis

Analyses were restricted to patients who were fully communicating a choice (maximum scores on the ability to express a choice scale of the MacCAT-T). This was done because we did not want to include participants where the nature of DMC is clearly different between medical and psychiatric patients (for example inability to communicate a choice because of impaired consciousness) or where interpretation of DMC is difficult (for example ambivalence). To enable analysis of appreciation and reasoning, we stratified the analysis by good and poor understanding - since we suspected that these abilities are difficult to rate accurately when understanding is poor. Analyses were conducted in Stata IC/10.1 on Windows to compute descriptive statistics, simple significance tests as well as perform receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis and logistic regression tests for effect modification.

Results

Our previous papers provide detailed descriptions of participation rates and differences between participants and non-participants. For the medical sample, we attained a participation rate of 53%, and completed 159 assessments, with 34 participants not fully expressing a choice, leaving a sample of 125 (79%) participants in the present analyses. For the psychiatric sample, we achieved a participation rate of 57% and assessed 200 participants. Of these, 36 individuals did not fully express a choice, leaving 164 (82%) participants for the present analysis. Table 1 shows the demographic features of the two groups. As expected, the psychiatric sample was younger, had more men, more individuals from Black and minority ethnic groups, more single people and more people living in supported accommodation than the medical sample. Table 1 also describes the principal diagnoses in the two groups. In the medical sample, cardiac, respiratory and infectious disorders dominated. Delirium and dementia were not listed as principal diagnoses, however 25% of the sample had impairments on the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE <24) Reference Folstein, Folstein and McHugh19 indicating cognitive impairment and such impairments were strongly associated with DMC. Reference Raymont, Bingley, Buchanan, David, Hayward and Wessely13 In the psychiatric sample, psychotic episodes, schizophrenia and affective disorders (bipolar and unipolar) were the primary diagnoses in over 80% of participants.

Table 1 Demographic and clinical characteristics, and principal diagnoses (ICD-10 categories) 18 of the two samples

| Medical hospital (n = 125) |

Psychiatric hospital (n = 164) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | ||

| Age, years: mean (s.d.) | 62.7 (20.5) | 39.6 (11.5) |

| Male, n (%) | 61 (49) | 107 (65) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| White | 105 (84) | 89 (54) |

| Black | 18 (14) | 65 (40) |

| Other | 2 (2) | 10 (6) |

| Married/partner, n (%) | 37 (30) | 24 (15) |

| Living situation, n (%) | ||

| Alone | 58 (46) | 73 (45) |

| With family | 57 (46) | 50 (30) |

| Supported accommodation | 9 (7) | 22 (13) |

| Other | 1 (1) | 19 (12) |

| Without DMC, n (%) | 37 (30) | 85 (52) |

| Principal diagnosis, n (%) | ||

| Cardiac | 34 (27) | |

| Respiratory | 30 (24) | |

| Infectious | 19 (15) | |

| Neurological | 7 (6) | |

| Gastrointestinal | 6 (5) | |

| Alcohol-related | 7 (6) | |

| Haematological | 3 (2) | |

| Cancer | 2 (2) | |

| Endocrine | 2 (2) | |

| Unknown medical disorder | 15 (12) | |

| Psychotic episode | 40 (24) | |

| Schizophrenia or related | 34 (21) | |

| Unipolar depression | 39 (24) | |

| Bipolar affective disorder | ||

| Manic episode | 17 (10) | |

| Depressive episode | 6 (4) | |

| Personality disorder | 14 (9) | |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | 3 (2) | |

| Organic brain syndrome | 4 (2) | |

| Other psychiatric disorder | 7 (4) |

DMC, decision-making capacity.

Previous analysis of age, gender and ethnicity showed that these variables were not associated with DMC independent of mental disorder. Reference Owen, David, Richardson, Szmuker, Hayward and Hotopf11,Reference Raymont, Bingley, Buchanan, David, Hayward and Wessely13 Further analysis in the sample used for the present analysis was consistent with this interpretation (not presented).

The scores for each ability according to DMC category and setting are shown in Table 2. Unsurprisingly, in each group, patients without DMC showed poorer performance on each ability. Although reasoning and appreciation had the same scales in each sample, understanding was on a 0-4 scale in the medical sample and a 0-6 scale in the psychiatric sample complicating direct comparison. The understanding scores showed a similar distribution in both samples. The median understanding score was shifted towards the middle of the scale in those without DMC and was at the top of the scale in those with DMC. In the psychiatric sample the median was shifted towards the bottom of the scale in patients without DMC and was around the mid-point of the scale in the medical sample without DMC. In patients with DMC the median for appreciation was at the top of the scale in both samples. In the medical sample reasoning scores were shifted down in patients both with and without DMC. In those without DMC the median was shifted right to the bottom of the scale in the medical sample, whereas it was in the top half in the psychiatric sample.

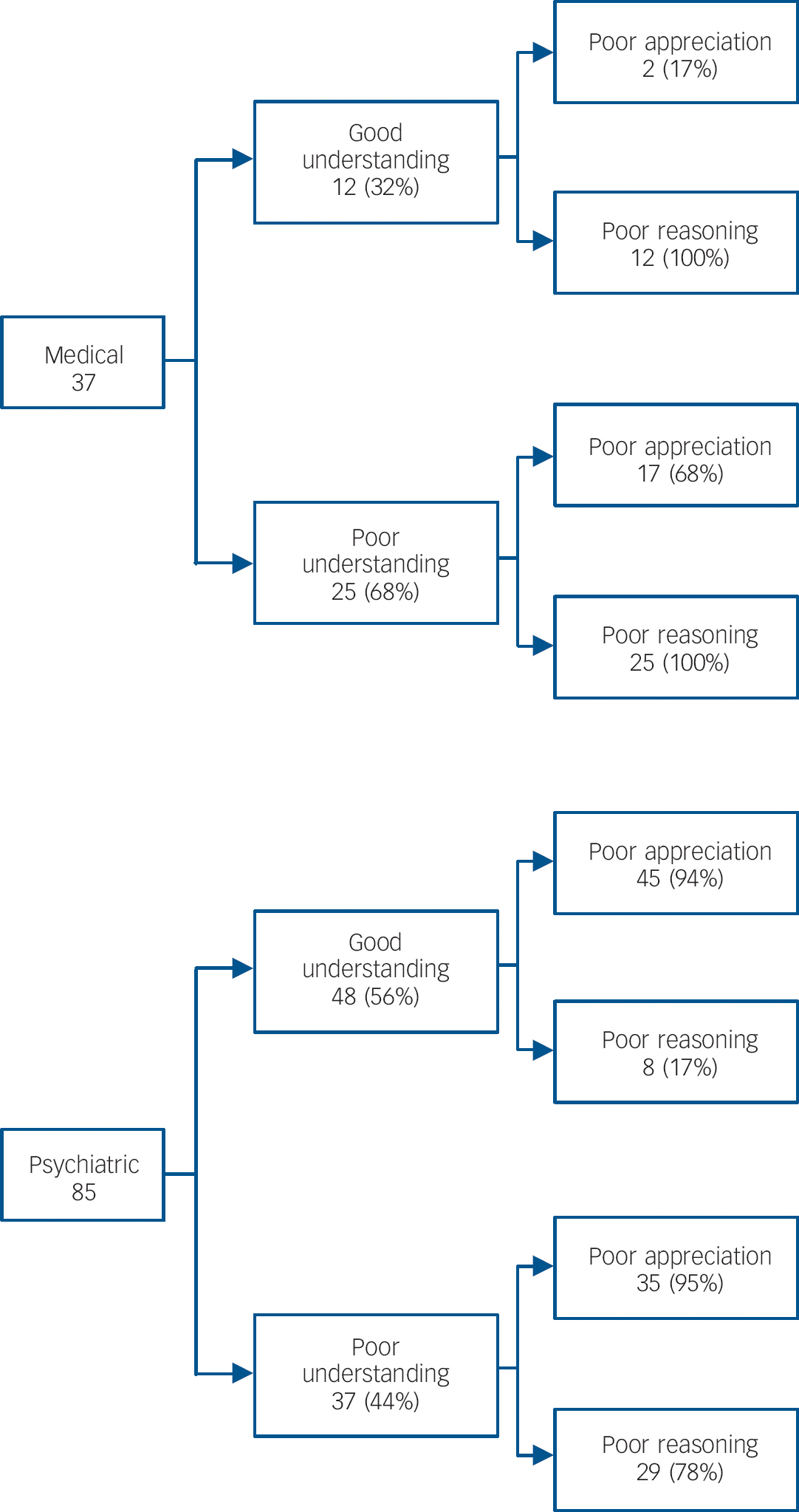

Table 3 shows the distribution of scores on appreciation and reasoning in patients who had poor understanding and for whom it is therefore difficult to engage in the process of informed consent. The majority of patients with poor understanding lacked DMC and there was no association between lacking DMC and being in a medical or psychiatric hospital (81% v. 93%, d.f. = 1, χ2 = 2.12, P = 0.14). For individuals without DMC, other abilities were also typically impaired - for example, 95% of the psychiatric group also had poor appreciation and 100% of the medical group also had poor reasoning. This table therefore indicates that if understanding is poor it is unlikely that the patient will have mental capacity and most patients will perform poorly on other abilities. There were a handful of individuals in whom understanding is assessed to be poor in whom capacity was judged to be present, but this small group typically had good scores on appreciation and/or reasoning.

Table 2 Descriptive statistics of legal abilities by hospital and decision-making capacity

| Medical hospital | Psychiatric hospital | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decision-making capacity, median (IQR) | Decision-making capacity, median (IQR) | |||||

| MacCAT-T ability | Scale range | With (n = 88) | Without (n = 37) | Scale range | With (n = 79) | Without (n = 85) |

| Understanding | 0-4 | 4 (3-4) | 2 (1-4) | 0-6 | 6 (5-6) | 4 (2-5) |

| Appreciation | 0-4 | 4 (3-4) | 2 (2-3) | 0-4 | 4 (3-4) | 1 (0-2) |

| Reasoning | 0-8 | 5 (4-6) | 1 (1-2) | 0-8 | 8 (7-8) | 5 (3-6) |

Each MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool - Treatment (MacCAT-T) ability was significantly lower in people without decision-making capacity compared with people with it (Mann-Whitney test; all P-values <0.0001).

Table 3 Patients with poor v. good scores on understandingFootnote a

| Medical hospital, n (%) | Psychiatric hospital, n (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | With DMC | Without DMC | Total | With DMC | Without DMC | |

| Poor understanding, total | 31 (25) | 6 (19) | 25 (81) | 40 (24) | 3 (7) | 37 (93) |

| Poor score on appreciation | 1 (17) | 17 (68) | 1 (33) | 35 (95) | ||

| Poor score on reasoning | 2 (33) | 25 (100) | 0 (0) | 29 (78) | ||

| Poor score on appreciation and reasoning | 0 (0) | 17 (68) | 0 (0) | 27 (73) | ||

| Good understanding, total | 94 (75) | 82 (87) | 12 (13) | 124 (76) | 76 (61) | 48 (39) |

| Poor score on appreciation | 2 (2) | 2 (17) | 4 (1) | 45 (94) | ||

| Poor score on reasoning | 25 (30) | 12 (100) | 0 (0) | 8 (17) | ||

DMC, decision-making capacity.

a. A poor score for each ability was defined as less than or equal to the mid-point of each scale and a good score was defined as more than the mid-point of the scale.

If understanding was adequate (Table 3) then a greater proportion of patients in the medical hospital had DMC compared with the psychiatric hospital (87% v. 61%, d.f. = 1, χ2 = 18, P<0.001). Table 3 indicates that patients with good understanding who fail the test of DMC do so for different reasons according to setting. In the medical patients, the small group with good understanding who lacked capacity, typically had adequate appreciation but all showed poor reasoning. For the psychiatric patients with good understanding who failed the capacity test, almost all had deficits in appreciation despite good reasoning.

These relationships are further explored in Tables 4 and 5. Table 4 shows sensitivities and specificities of appreciation and reasoning as though they were ‘tests’ of DMC in individuals with adequate understanding, stratified by setting. This shows that for medical patients, reasoning is a sound test for DMC - with high sensitivity and specificity, whereas appreciation has a very low sensitivity. For psychiatric patients the pattern is reversed: appreciation has excellent sensitivity and specificity, but reasoning appears a poor test, with low sensitivity.

When continuous scores of appreciation and reasoning were used in patients with good understanding, areas under the receiver operating curves differed significantly for both appreciation and reasoning according to hospital type (Table 5). Appreciation was a better predictor of impaired DMC in the psychiatric hospital and reasoning a better predictor in the medical hospital. On a more stringent test of effect modification by hospital site, this interaction between site and ability was only significant for appreciation (odds ratio for site×appreciation 0.16, P = 0.02; odds ratio for site×reasoning 1.2, P = 0.72).

Figure 1 gives an overview of the abilities in patients without DMC.

Table 4 Sensitivities and specificities of poor appreciation and poor reasoning as ‘tests’ for decision-making capacity in patients with good scores on understandingFootnote a

| Medical hospital (n = 94) | Psychiatric hospital (n = 124) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Specificity | Sensitivity | Specificity | |

| Poor score on appreciation | 0.17 | 0.98 | 0.94 | 0.95 |

| Poor score on reasoning | 1.00 | 0.70 | 0.17 | 1.00 |

a. Good score on understanding was defined as more than the mid-point of the scale (i.e. >3 in the psychiatric hospital and >2 in the medical hospital).

Table 5 Hospital comparison of receiver operating characteristic (ROC) areas for appreciation and reasoning as tests of decision-making capacity in patients with good understanding

| Medical hospital | Psychiatric hospital | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | ROC area under curve | n | ROC area under curve | χ2 (d.f. = 1) | P | |

| Appreciation | 94 | 0.69 | 124 | 0.97 | 11.83 | 0.0006 |

| Reasoning | 94 | 0.95 | 122 | 0.84 | 5.22 | 0.02 |

Fig. 1 Patients able to express a choice but without decision-making capacity.

Discussion

Main findings

For most patients who are able to express a choice but in whom understanding was rated to be poor, DMC was absent, and this was unrelated to the type of hospital they were in. Among patients able to understand information and express a choice, a higher proportion lacked DMC in the psychiatric hospital compared with the medical hospital (39% and 13% respectively). In these patients, the medical patient sample typically had poor reasoning associated with lack of DMC, whereas the psychiatric patients typically had poor appreciation.

Strengths and limitations

This study has limitations. Formal diagnoses of dementia or delirium were not made in the medical sample and psychiatric comorbidity (such as depression) was not analysed. However, the prevalence of cognitive impairment in this medical sample was high at 25%, with a strong association to loss of DMC. Reference Raymont, Bingley, Buchanan, David, Hayward and Wessely13,Reference Kim20

The assessments conducted in these two studies were made by different research clinicians at different times. This introduces the possibility of observer biases. However, there was high interrater reliability Reference Raymont, Buchanan, David, Hayward, Wessely and Hotopf16,Reference Cairns, Maddock, Buchanan, David, Hayward and Richardson17 and the judgements of DMC were checked by the same panel of experienced clinicians. We think it unlikely that the interpretation of DMC changed significantly in the period between the two clinical researchers' work in the medical and psychiatric hospital. We used psychiatrists to assess DMC - which reflects usual clinical practice, and although DMC is a legal, social and ethical concept the courts have looked to clinical expertise in their rulings on DMC. Using doctors with knowledge of psychopathology is therefore a strength of the study. However, some might argue that anthropologists or other social scientists may be better attuned than doctors to understand the relationships between patients' explanations and their cultural or religious background.

The MacCAT-T has often been used to collect scores without judgement of DMC and without clinical assessment, so a limitation to this study may be the way the tool is incorporated into clinical contexts and shaped by them with loss of objectivity. However, use of earlier versions of the MacCAT-T in clinical settings along more de-contextualised, psychometric lines received criticisms with regard to validity. Reference Kapp and Mossman21 Its authors developed the MacCAT-T, in part, to promote the incorporation of a tool into clinical and psychosocial assessment in a way that was both practical and flexible. Reference Grisso and Applebaum22 The MacCAT-T, although potentially reliable, has short scales with limited ranges. The subscales have different ranges and we were forced to use a fairly crude definition of impairment (scoring below the halfway point on each scale). This limits statistical analysis and was complicated by the different scales we used for understanding in the two samples.

To our knowledge this is the first study to explicitly compare patients in two settings - psychiatric and medical. Other studies have described abilities in different diagnostic groups, but typically have not compared these with the criterion of whether the individual does or does not have DMC. Reference Grisso and Appelbaum23-Reference Marson, Cody, Ingram and Harrell26 We therefore think this study adds helpful data to the literature. Next, we consider the four decision-making abilities in relation to our data before briefly discussing how our understanding of DMC might be advanced.

Understanding

The understanding ability is a pre-requisite for a patient's consent, or refusal, to be ‘informed’. To assess understanding it is necessary to ensure that information has been given to the patient in a manner clear enough to be understood. Grisso & Appelbaum advise beginning the capacity assessment with information disclosure and to test whether the patient has understood it by inviting them to paraphrase. Reference Grisso and Applebaum22 Memory, language and attention impairments are likely to interfere with this understanding ability as are altered emotional states or thought disorder. There is a question about how far the assessor, or systems around the assessor, need to go to adjust for, augment or ‘scaffold’ Reference Anderson, Forst, Hartmann, Jaeggi and Saar27 these disabilities to enable the patient to understand. The general principle is that assessment of DMC must ensure that lack of DMC is not founded on poor understanding when understanding has not been enabled or supported. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities 28,Reference Bartlett29 emphasises a right to this kind of support and it also features in DMC law. Reference Grisso and Applebaum22,30

How is poor understanding related to DMC? Our data indicate that poor understanding is usually inconsistent with DMC; few patients with poor understanding were judged to have DMC. But poor understanding alone does not seem to be the determining factor. The few with poor understanding with DMC had good appreciation or reasoning and those with poor understanding without DMC almost always had poor appreciation or reasoning as well. So we suggest that if there is lack of DMC with poor understanding, this typically reflects not poor understanding alone, but poor scores in two or all three of the abilities in question.

What of good understanding? Is it enough for DMC? Our data indicate, in both medical and psychiatric settings, that it is not enough. A fair percentage show good understanding but lack DMC because of poor appreciation or reasoning. Our data therefore suggest that poor understanding alone is neither a strong necessary nor sufficient condition for a lack of DMC and that understanding needs to be considered in relation to appreciation and reasoning to have a bearing on DMC.

Appreciation

Grisso & Appelbaum Reference Grisso and Applebaum22 suggest that a patient's non-acknowledgement of the diagnosis and recommended treatment should be counted as a failure of appreciation only when patients' choices are based on premises (beliefs) that: (a) are substantially irrational, unrealistic or a considerable distortion of reality, (b) are the consequence of impaired cognition or affect, and (c) are relevant to the treatment decision. Saks and colleagues Reference Saks and Behnke31,Reference Saks, Dunn, Marshall, Nayak, Golshan and Jeste32 have elaborated on (a) with a concept of ‘patently false belief’ with the aim of finding a standard between, on the one hand, impossible belief and, on the other, making doctors the final authorities on truth. Grisso & Appelbaum characterise appreciation as ‘the ability to apply the information abstractly understood to his or her own situation’. Reference Grisso and Applebaum22 Our data suggest that this ability is a more critical variable for DMC in the psychiatric hospital than in the medical hospital. The MacCAT-T however only captures this ability with two questions and a 0-4 scale (see the Appendix for the two questions and guidelines on rating inability).

Reasoning

Decision-making capacity law separates the decision-making process from the decision itself (otherwise the DMC test would become an ‘outcome test’). Grisso & Appelbaum Reference Grisso and Applebaum22 address this by focusing on the ability to ‘manipulate information rationally’, that is, ‘to engage in logical processes when using the information that they have understood and appreciate in arriving at a decision’. The essence of the ability, according to Grisso & Appelbaum, is ‘engaging in a process of weighing treatment options’. Caution needs to be exercised in interpreting this as a procedural reasoning standard, as there is plenty of evidence to suggest healthy human decision makers do not conform reliably to formal reasoning. Reference Sutherland33,Reference Owen, Cutting and David34 Caution also needs to be exercised in interpreting this as a substantive reasoning standard because the Mental Capacity Act 2005 states ‘a person is not to be treated as unable to make a decision merely because he makes an unwise decision’. Grisso & Appelbaum adapt a loose standard and draw attention to the connection that any reasoning inability must have to the disorder. An example of the questions the MacCAT-T uses to probe the reasoning ability is given in the Appendix together with the guideline on rating inability. Our data suggest that the reasoning ability is a more critical variable for DMC in the medical than in the psychiatric hospital.

Values and evaluation

Values and evaluation is arguably a feature of all of the above abilities Reference Kim20 but in relation to appreciation this seems particularly salient. With regard to the patient with anorexia who values thinness over and above life, Grisso & Appelbaum argue that the evaluative inability is included in an inability to appreciate. Reference Grisso and Appelbaum35 On MacCAT-T appreciation, the person is being assessed, in effect, on their ability to take reality as it is. How this is to be separated from the value judgements of society in general and from medical expertise in particular has been controversial as indeed has the question of whether it ought to be so separated. Reference Freyenhagen and O'Shea36 The Mental Capacity Act specifies DMC abilities somewhat differently to the four-ability model. Instead of referring to appreciation and reasoning abilities it specifies an ability to ‘use or weigh’. On the question of evaluation we may ask what was in the minds of the legislators when these words were being examined by them. The following Reference Hansard37 is an extract from an exchange between the government minister (Baroness Ashton) and the leader of the opposition (Earl Howe) in the House of the Lords during the parliamentary passage of the Mental Capacity Bill. Earl Howe sought to amend ‘use or weigh’ to ‘use, evaluate or weigh’.

Earl Howe: My question relates to individuals with depression. One of the features of those who are afflicted with depression is that they do not view the world in a normal way… their view of life is of something colourless; they are often preoccupied with intense feelings of self-denigration; and they lack hope… the decision-making process is skewed by those features of their illness. They do not use or weigh information in a normal way…

Baroness Ashton of Upholland: I understand what the noble Earl, Lord Howe, seeks to do, and I recognise that the amendment is probing. We think that the wording we have used incorporates evaluation as well…

Decision-making capacity assessment within the Mental Capacity Act thus seems to require an assessment of evaluative ability via ‘use or weigh’. Reference Tan, Stewart and Hope38

Advancing understanding of DMC

Although difficult concepts may only afford so much definitional precision, clinicians working in medical or psychiatric settings need to be aware of the relevant decision-making abilities and guard against idiosyncratic or erroneous interpretation. Our data suggest that clinicians, when assessing DMC, need to be sensitive not only to the decision at issue and its gravity or risk Reference Kim, Caine, Currier, Leibovici and Ryan39 but also to the kind of disorder - i.e. whether it is medical or psychiatric.

Some may fear that this sort of sensitivity to diagnosis could allow prejudicial assumptions to compromise the objectivity of DMC assessment. We think two observations are in order in connection with this concern. First, it is important to emphasise that sensitivity to diagnosis in the assessment process is not at all equivalent to a ‘status’ account of capacity or competence. The best protection against prejudicial assessments is not blindness to diagnosis, but insistence on a high standard of reason-giving in the conduct of assessments. Second, we would echo Gadamer's warning about the so-called prejudice against prejudice. Reference Gadamer40 The assessment of DMC is an interpretative endeavour, and interpretation always takes place in a context in which the interpreter arrives with orienting ‘pre-judgements’. Eliminating pre-judgement altogether would not lead to objective interpretation; it would make interpretation impossible. Objectivity is thus best served when pre-judgements are themselves responsive to evidence, subjected to critical scrutiny, and open to challenge and revision.

In advancing our understanding of DMC, it is worth pausing over one suggestive feature of Earl Howe's description of the way that depression can threaten DMC. He describes how the ‘world’ looks to the person with depression. Here the focus is not so much on the processing of information in the production of a decision, nor is the issue one of abnormal values. The question is rather whether DMC can be threatened by the distinctive way in which an individual encounters and makes sense of their world. Can the nature of that encounter itself disrupt DMC? If so, does it disrupt certain sorts of decisions but not others? Earl Howe's observation suggests that assessment of the ability to ‘use or weigh’ can sometimes require a distinctive skill-set on the part of the assessor: Reference Martin and Hickerson41 for example, the skills of understanding and unpacking the ways in which people with depression encounter the world in which their decisions must be made. More work will be required to translate that understanding into publically attestable judgements of whether such individuals have the abilities to decide for themselves about treatment - literally, make that decision their own. Reference Owen, Freyenhagen, Richardson and Hotopf42

Implications

Decision-making capacity is a concept that now crosses psychiatric and medical practice. Using a validated interview - the MacCAT-T - we show some evidence that appreciation and reasoning differ in their association with DMC judgements in psychiatric and medical settings. Both the appreciation and reasoning abilities and the ‘use or weigh’ abilities are normative abilities in that they all derive their meaning from the right to self-determination, or individual autonomy. Reference Owen, Freyenhagen, Richardson and Hotopf42,Reference Banner43

Law can tend towards assumptions that medical in-patients choose treatment autonomously and that psychiatric in-patients are of ‘unsound mind’ in relation to treatment. 44 Those assumptions are not well supported by evidence. Reference Owen, Richardson, David, Szmukler, Hayward and Hotopf12,Reference Raymont, Bingley, Buchanan, David, Hayward and Wessely13,Reference Okai, Owen, McGuire, Singh, Churchill and Hotopf15,Reference Fassassi, Bianchi, Stiefel and Waeber45 Policy-making is moving beyond these assumptions and debating whether DMC law is evolving to recognise differences in kinds of mental disorder or disability that obviate the need for two streams of mental health law. Reference Richardson46 This study adds data which, we hope, give some nuance to this policy debate and helps clinical and legal practitioners recognise that DMC assessment requires attention to the kind of mental disorder or disability present, as well as to the kind of treatment decision.

Appendix Examples from the MacCAT-T of how appreciation and reasoning abilities are probed, with guidelines on inability

| Ability | Example probe | Guidelines on inability |

| Appreciation | ‘That is what we [your doctors] think is the problem in your case. If you have any reason to doubt that, I'd like you to tell me so. What do you think?’ | Patient clearly does not agree that he or she has the disclosed disorder, with reasoning based on a delusional premise or some other belief that seriously distorts reality and does not have a reasonable basis in the patient's cultural or religious background. |

| OR | ||

| Patient believes that the symptoms are related to circumstances other than a medical/psychiatric disorder (e.g. psychotic symptoms seen as consequences of work-related stress). | ||

| OR | ||

| Patient clearly disagrees with symptoms or disorder, but with no comprehensible explanation offered. | ||

| ‘You might or might not decide that this is the treatment you want - we'll talk about that later. But do you think it's possible that this treatment might be of benefit to you?’ | Patient acknowledges at least some potential for the treatment to produce some benefit, but for reasons that appear to be based on a delusional premise or a serious distortion of reality. | |

| OR | ||

| Patient does not believe that the treatment has the potential to produce any benefit, and offers reasons that appear to be delusional or a serious distortion of reality. | ||

| Reasoning | ‘You think that treatment X might be best. Tell me what it is that makes that seem better than the others.’ | Patient can make no comparative statements. |

Funding

This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.