I COINS IN THE ROMAN PROVINCES

Roman coinage forms an astoundingly rich body of material. That applies to coins struck by the centre as much as so-called provincial coinage. The latter can be roughly categorised as 1) coins struck by cities in the east of the Roman Empire, and for the Julio-Claudian period also in the west (in the western provinces, cities stopped issuing coins around the end of Claudius’ reign); 2) coinages issued in the name of federations of cities (koina) or coins celebrating alliances between cities (so-called homonoia-coins); 3) coins struck by ‘friendly kings’; and 4) so-called ‘provincial issues’ — mainly drachms, didrachms and tetradrachms, but also bronzes — that were mostly struck by important mints such as Alexandria, Antioch and Caesarea (in Cappadocia), probably under the supervision of Roman magistrates, to circulate in specific provinces.Footnote 1

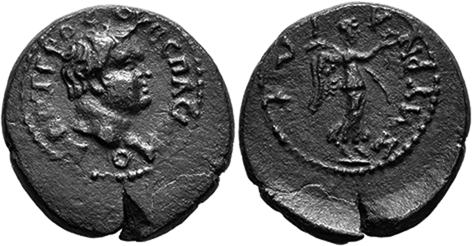

These various coins provide very useful information on a wide range of subjects. Through their iconography and legends, they allow us to ask questions about the expression of local identities, the relationships between different cities or the names and functions of imperial officials or members of local elites. Provincial coinage was, furthermore, issued for emperors or members of the imperial family, including otherwise rarely attested individuals, such as Domitian's cousin Vespasian the Younger, who is visible on the obverse of three coins from Smyrna, but never on central coinage (Fig. 1).Footnote 2 Provincial coinage also, of course, has implications for our understanding of monetisation in the Roman world. In the past decades, an immense amount of work has been done to make these coins readily available to historians of the Greek and Roman worlds. Of the utmost importance are the Roman Provincial Coinage (RPC) series, which provides a comprehensive typology of provincial coinage, and the Coin Hoards of the Roman Empire (CHRE) project, which assembles information about hoards of all coinages in use in the Roman Empire. Both of them have immensely enriched the possibilities for research into the Roman world. This review article aims to give an overview of where the RPC and CHRE projects are in terms of completion, and how classicists can make use of this exceptional material, asking entirely new questions and tracing wide-ranging developments. ‘Provincial coinage’, to make clear from the outset, is an umbrella-term of convenience, which has rapidly replaced the previously dominant use of ‘Greek imperial coins’ in academic debate.Footnote 3 The common denominator is that these coins were intended for use in the regions beyond the Italian peninsula, and were mostly not struck under central imperial control.

FIG. 1. Smyrnian bronze coin (19 mm), c. a.d. 94/5, with Vespasian the Younger on obverse (RPC II 1028): Leu Numismatik AG, Web Auction 18.1953. (Courtesy Leu Numismatik.)

II THE RPC PROJECT

Thirty years ago, Andrew Burnett, Michel Amandry and Pere Pau Ripollès published the first volume of the RPC series. They chose systematically to assemble and analyse all coin types that were not included in the Roman Imperial Coinage (RIC) series.Footnote 4 The latter records every published coin type issued by the centre (the emperor and those surrounding him) from 31 b.c. to a.d. 491. The purpose of RPC was to provide a standard typology of provincial coinage. This means that, like RIC, the RPC catalogue does not assemble individual specimens, but provides a systematic overview of coin types. RPC does not, therefore, replace the various excellent die-studies of particular mints produced over the years. Yet by providing a systematic treatment of provincial coins, RPC has rapidly established itself as a fundamental research tool for numismatic research, standing along the now digitally available RIC.Footnote 5 The core of the RPC catalogue were the ten main numismatic collections of London, Paris, Berlin, Munich, Vienna, Copenhagen, New York, Oxford, Cambridge and Glasgow. These were supplemented with additional material from trade literature and publications of hoards and excavations and from examination of coins in public and private collections, especially from Spain, to do justice to the coins from the western provinces. Many of these local coin types were previously difficult to find, and impossible to compare systematically. Suddenly, it became not only possible but even easy to check where which provincial coin types had been issued and how the striking of local coins in certain cities or regions developed over time. The project was, from the beginning, rightly hailed as an essential contribution to the study of the Roman world.Footnote 6

Roman provincial coinage is an apt term to describe the group as a whole, as these coins form an important source of information about life in the Roman provinces. Legends and imagery on the coins often took local considerations into account. From the start, the RPC project intended to catalogue all provincial coin types up to Diocletian's currency reforms (a.d. 295), which marked the end of local mintage in Egypt.Footnote 7 In the past thirty years, it has progressed far in this direction.

Two developments stand out. The first is the continuing publication of volumes, consistently well produced. Since the appearance of Volume I two decades ago, volumes have come out at a steady rate. The intervals have been substantial, but this is unsurprising, given the ambitions and scope of the project. Volume II, on Flavian coins, appeared in 1999, followed after another seven years by Volume VII.1 (2006), which assembled coins issued under the Gordians (a.d. 238–244,) though only those from the province of Asia. Its sister volume (VII.2) has recently been published (September 2022). Volumes III (a.d. 96–138) and IX (a.d. 249–254) appeared in 2015 and 2016. The various volumes differ substantially in the number of coins assembled, with, for example, the number of cities minting coins, and the average number of coin types per city, increasing significantly in the Antonine period, which is why there are, or will be, multiple parallel volumes for the period after a.d. 138. The result of progress so far is that there is a full overview in print of provincial coin types from the period 44 b.c.–a.d. 138 and for a.d. 249–255.Footnote 8 Volume IV.4, on Antonine coins from Egypt (which means Alexandria), will also appear sometime in 2022. Other volumes are at various stages of completion, but without clear expected publication dates.

These volumes offer more than their catalogues, though they are their core. All have extensive and excellent introductory chapters, supplying historical backgrounds to the period under discussion, and also to the cities and regions minting coins. These chapters also analyse patterns, indicating which authorities coined for different emperors, which cities and regions struck specific types of coins and what developments there were in coin types and denominations and in designs and legends, with attention to depictions and titles of emperors and members of the imperial family on the obverses and the often local interest of reverses. These introductions follow similar formats for the different books (they are identical for volumes I–II, but somewhat adapted for the later volumes). The published volumes, then, have truly changed the possibilities for scholars of the ancient world to incorporate the different coinages from the Roman provinces in their analyses. This, in itself, is a major achievement.

The second main development, which could not have been anticipated in 1992 but has greatly increased the value of the project, has been the development of the Roman Provincial Coinage Online database and website (https://rpc.ashmus.ox.ac.uk/). It is directed by Jerome Mairat and Chris Howgego, the former of whom is also responsible for the current website. In terms of content, RPC Online incorporates not only all the coins from the published volumes, but also subsequent additions. As provincial coins were issued in fairly small quantities, new coin types relatively regularly resurface, either through the publication of collections that were previously not accessible, or through being unearthed and made available through systems like the Portable Antiquities Schemes.Footnote 9 This is very different from central coinage, where new types are rarely found, and almost always cause massive academic debate, as was the case for the Augustan Leges et Ivra P R Restitvit coin, auctioned in the very year in which RPC I was published, or the Antoninanus issued for Domitian II found through metal-detecting in 2003.Footnote 10 The catalogue of Roman provincial coins, in other words, will remain to some extent a work-in-progress, even when the RPC project is brought to fulfilment, in contrast to the much more static collection of Roman imperial coin types. The supplements to the various published volumes of RPC give a sense of scale. Published supplements to the volumes up to 2019 added more than 500 pages of provincial coin types. All these ‘new’ coin types have been included in the RPC Online database which makes the publication of further supplements unnecessary (and means that the printed supplements are effectively out of date), which is one benefit of the digital collection.Footnote 11 It also indicates how much time and effort will have to be spent on keeping the database up to date.

Just as important as the supplements to the published volumes is the inclusion of the catalogues of volumes which are still in progress. Coin types from unpublished volumes are given temporary numbers pending print publication, but all information about the coins, including images, is available for consultation well in advance.Footnote 12 This has, of course, greatly increased the reach of the project. At the moment, only RPC V (a.d. 193–218) and X (a.d. 253–297) are not digitally available. Consequently, RPC Online has a full representation of coin types struck in the provinces between 44 b.c.–a.d. 192 and a.d. 218–253.Footnote 13 All told, the database currently contains approximately 47,000 entries. The level of completeness on the RPC website is clearly impressive, coming close to realising the project's ambition of providing a standard typology for the provincial coinage.

The website does not include the introductions to the various volumes, but provides a brief introduction of its own, with useful links and bibliographical references. It also provides links to additional (online) resources for studying provincial coinage, relevant maps, lists of countermarks and magistrates and some tabulations of the number of coins per reign, client king or region. It is not meant to compete with the much more thorough introductions to the published books, and these are the main reason to continue to consult the print versions. For all other purposes, the website is now superior. Even though a lot of work clearly went into supplying the printed volumes with useful indices, they cannot compete with the search possibilities of a digital environment. The current iteration of the website allows search by volume, mint location (city, region, province, alliance), chronology (reign, person on the coin, magistrates, date range), obverse and reverse legend (with easy Greek typing incorporated), obverse and reverse design and physical characteristics (metal, weight range and diameter range). It also allows for search results to be tabulated, and for issuing mints to be displayed on an integrated map. So even though the project is some way from completion, the web application is an extraordinarily powerful research tool.

iii rpc and roman historians

The RPC project, especially its online interface, opens up an astounding range of avenues of research. At the most basic level, it makes it possible to investigate how frequently specific types of coins were issued in various regions, and how this changed over time. Yet the assembled material also offers insights into the impact (or lack of impact) of the Roman Empire on almost all aspects of civic life in the provinces, and about how that impact was perceived. To illustrate just some of these possibilities, we give examples from the political, religious and economic spheres.

First, the political. Most obviously, the available provincial coinage makes it possible to trace the development of imperial portraiture and titulature in the various areas of the Roman empire. These are conveniently included in the published introductions, showing among other points the amazing variety in imperial titulature in legends.Footnote 14 But the fact that the Roman emperor became the standardised obverse type is a noticeable observation in its own right, as is the speed with which this process took place.Footnote 15 The number of coin types struck under the various emperors is tabulated in the website (https://rpc.ashmus.ox.ac.uk/reign), showing the multiplication of types over time. It is also easy to trace who was depicted on the obverse of the coins (Table 1).Footnote 16 Of course, these numbers can only be a rough guide to the coinage as a whole. The main purpose of RPC is to produce a standard typology of the provincial coinage of the Roman Empire. This is different from providing a full overview of all extant provincial coins. Different types may have been minted in different numbers. Detailed hoard analysis is a better, though still imperfect, guide to the actual composition of the coinage.Footnote 17 But the quantification of types can still be a useful exercise, as long as the frequencies calculated are recognised as just a rough proxy for the distribution of all coins. Here, the trend is clear.

Table 1. Provincial coin types depicting the imperial family.

*It is noticeable that there are only twenty-seven types depicting Titus and Domitian, which is a marked difference with central coinage, where 192 Vespasianic types show the sons together: http://numismatics.org/ocre/; search term ‘Titus and Domitian’. Cf. Claes Reference Claes2013: 70–2, 164–6.)

This brief overview instantly demonstrates how dominant the image of the emperor in the provinces rapidly became, and also suggests increased visibility of important members of the imperial family when they were uncontested (wives or sons who were indicated as probable heirs). Like central coinage, provincial coinage paid more attention to living members of the imperial family than to ancestral (deified) ones.Footnote 18

These numbers, and the ease with which these overviews can be created, tabulated and placed on a map (with one click), give a real and rapid sense of the numismatic presence of imperial portraiture in the provinces, and of the choices regions and cities made in associating themselves to the centre. Local considerations will often have been decisive. All provincial coins depicting Uranius Antoninus (a rival of Trebonianus Gallus in a.d. 253) were struck in Syrian Emesa. They make up eighty-seven of the 107 local coin types (all the other coins were issued for Antoninus Pius), making it likely that Emesa was a key location in Uranius’ bid for power. For the contemporary and short-reigning emperor Aemilian (a.d. 253) there are sixty-four entries in the RPC database, but divided over more locations: not only the mints of Viminacium, Parium, Iulia-Ipsus, Side, Amisus and Aegeae, but also the colony of Pisidian Antioch and the provincial mint of Alexandria. The list is somewhat haphazard, making it likely that local officials and their relation to or knowledge of new emperors played an important role in deciding which cities minted coins for which emperors.Footnote 19

RPC also contains invaluable information about local magistrates and where and how they interacted among themselves and with the emperors. Thus, several coins from Smyrna were explicitly struck under the auspices of the sophist Marcus Antonius Polemon (c. a.d. 90–144), whose name is on the reverse, and had a portrait of Hadrian's deified lover Antinous on the obverse (Fig. 2).Footnote 20

FIG. 2. Smyrnian bronze coin (39 mm), c. a.d. 134–135, issued under M. Antonius Polemon (RPC III 1978), Hunterian Museum: GLAHM:42506. (© The Hunterian, University of Glasgow.)

The iconography chosen for the reverse (bull and panther motifs) was new for Smyrna, but was used elsewhere to associate Antinous to Hermes and especially Dionysus. This linked the coins back to Polemon in a different way, since he held an important priestly role in the local festival dedicated to Dionysus.Footnote 21 Polemon's coins, then, connected Antinous to the local Dionysus cult, and to Polemon's own religious office. These coins did not depict the emperor, but it is clear that closeness to the ruler was implied. The various magistrates named on provincial coinage are conveniently assembled (https://rpc.ashmus.ox.ac.uk/magistrate) and can be arranged by city, reign or name of the magistrate. This makes it easy to find that, for instance, Cl. Rufinus was strategos at Smyrna under Gordian III.Footnote 22 Louis Robert used these coins to identify the Rufinus who appears in the Martyrdom of Pionios, an identification that played a central role in his demonstration that Pionios was martyred during the Decian persecution (not under Marcus Aurelius, as claimed by Eusebius) and that the text was based on an eye-witness source.Footnote 23 This sort of prosopographic information allows for wide-ranging research on the role and identity of local mint-magistrates, such as the extent to which they overlap with local elites attested in honorific epigraphy and literary sources. Preliminary work has been done in this field, but there is immense scope for further exploration.Footnote 24 Similarly, the tabulated list of coin types by city (https://rpc.ashmus.ox.ac.uk/city) allows for easy overview as to which cities only issued very rarely. For instance, Singara (in northern Mesopotamia) only issued seventeen coin types, all of them for Gordian III and Tranquillina, which suggest some sort of direct link between emperor and town.Footnote 25

Second, the religious sphere. Religious themes are ubiquitous on Roman provincial coins. Cities and regions expressed their identities on coinage mainly through depictions of patron deities or mythological figures closely associated with the history of the particular town or area.Footnote 26 An illustrative example is the coinage issued in Corinth, on which deities and myths that were of importance to this city, such as Poseidon, Aphrodite, Melicertes and Pegasus, figured widely. With the help of RPC it is now possible quickly to map the importance of specific divine or mythological figures for a certain city or area in a specific period and thus to draw comparisons between different locations and/or different periods. When we look at locally minted coins that refer to Asclepius, for example, a simple search on the RPC website demonstrates that out of 1,071 Asclepius types produced by 200 cities, 10 per cent of types were issued in Pergamum. This is, of course, not surprising, since Pergamum contained one of the most important cult places related to Asclepius. However, our search also reveals that most Asclepius types were produced under the Antonines (Antoninus Pius, 12.4 per cent; Marcus Aurelius, 10.3 per cent; Commodus, 12.7 per cent). The numbers under Commodus are particularly noticeable, since the total number of coin types issued during his reign (2,598) is substantially smaller than those under his two predecessors (5,359 and 5,475 respectively).Footnote 27 Although this analysis of coin types can only provide a rough guide to patterns in the coinage, the concentration of coin types in these reigns is noticeable. This suggests that RPC not only gives insights into particular religious trends in the provinces but also provides us with the possibility to see the impact of imperial actions on local cults. The surge in the production of local Asclepius coins under the Antonine dynasty may well reflect the imperial patronage of Asclepius’ cult from the reign of Hadrian. Whether these numbers are comparable with the number of Asclepius types that were issued under the reign of Caracalla, who also had a special connection with the healing god, will become clear when the coin types minted for this emperor are also included in the RPC database, hopefully at some point in the near future.Footnote 28

Another example which nicely demonstrates the impact of empire on local cult life is the way in which temples that were erected for the veneration of the emperor figured on provincial coins. In this particular case, it is not yet possible to make full use of the potential that RPC offers. Some of these temples can be traced by means of searching for ‘neokoros’ in the legends of the coin types that are listed in the RPC database. This type of search will not, however, result in a complete overview of temples related to the imperial cult, as the term ‘neokoros’ does not cover all images of temples in which the emperor was worshipped. Yet, when performing a general search for images of temples in the RPC database, it is not possible to filter out imperial sanctuaries or to sort the search results in the tabulated view. The latter problem also applies for the OCRE website, but that database allows for exporting search results to a CSV file; something which would also be of tremendous use when deploying the RPC database as a research tool.

Finally, there is the possibility of using provincial coinage to address economic questions. The end of provincial coinage in itself is a case in point. When, during the reign of Diocletian, the mint of Alexandria stopped issuing tetradrachms but instead minted imperial coinage, the Roman state finally presided over a unified monetary system in which coinage was produced by mints located in various places in the Empire.Footnote 29 That was the end result of a gradual process, with the local mints beginning to disappear from the end of the Severan era, and koinon coinage ending first in the Greek mainland and Balkans, and then in Asia Minor. How that trajectory played out cannot yet be traced easily through the RPC project, as Volume X (a.d. 253–297), under the direction of William Metcalf, is still ‘in progress’. Yet for the period which is (digitally) available, it is easy to trace the number of coin-issuing cities at different periods and place these on custom-made maps (Fig. 3a–c).Footnote 30

FIG. 3. Mints producing provincial coinage, by period: (a) a.d. 69–96; (b) a.d. 138–192; (c) a.d. 249–254.

These maps make the rise and decline of the number of mints instantly visible. They also clearly illustrate the geographic ‘lumpiness’ of the distribution of mints. Provincial coinage was always heavily dominated by mints in the Roman province of Asia (and to a lesser extent Pontus-Bithynia, Cilicia, Thrace, Pamphylia and Syria), and this tendency became if anything even more accentuated over time. It is also curious that Lycian cities never struck provincial bronze, although cities in Pamphylia, the other half of the joint province, did. As these maps make clear, ‘Roman provincial coinage’ is not at all the same as coinage in the Roman provinces. Local differences were of the utmost importance: only in the province of Asia do we find tiny towns striking their own coinage. Provincial bronze as a form of civic self-representation was never anything like a universal phenomenon.

The RPC project is also extremely helpful when analysing the ways in which cities shared dies when striking coins. As we have seen above, local content mainly appears on the reverse of provincial coinage, with the obverse reserved for emperors or members of the imperial family. These obverses are sometimes identical for several cities, indicating that they used the same die. This means either that there was more centralisation in coin-striking than assumed or that dies (or craftsmen using these dies) were moved between cities. When and how these dies were shared, and how the process developed, tells us much about interrelation between cities. RPC makes it possible to compute statistics about the number of shared dies per year and numbers of die-sharing cities, as was recently expertly done by George Watson (Table 2).Footnote 31

Table 2. Statistics on shared dies for cities in Asia Minor.

There is a noticeable increase in the Severan period (a.d. 193–238), and then again in the years a.d. 238–244, followed by a slow decrease, though numbers still remain well above Antonine levels (a.d. 98–138). The peak in the reigns of the Gordians may partly be a result of the state of publication. RPC VII.1 (which has assembled the material for that period) is based upon a complete die study and gives a comprehensive catalogue, rather than collecting (and then completing) material from the core collections as the other volumes do. Still, it is noticeable that die sharing seems not to have been used as a solution as cities faced increasing difficulties in striking their own coins. One might have expected collaborative efforts to become more common when the numbers of mints decreased due to external factors in the third century; instead, the number of die-sharing cities decreases.Footnote 32

Alternatively, the analysis of provincial coinage allows researchers to look at debasement of coins, for instance through the switch by the mint of Antioch from heavily debased tetradrachms to Antoniniani, or by searching by ‘metal’ (part of the ‘physical characteristics’ section of the advanced search options) and noting how ‘debased gold’ types feature heavily in the Bosporus kingdom.Footnote 33 Again, hoard data would be required for a more robust analysis, but the completeness of RPC and its easy-to-use interface is extremely helpful for establishing rough patterns.Footnote 34 Remaining on the subject of material fabric, it is noticeable that there are no datable leaded bronze coins after the reign of Domitian. Metal, size and weight (all included in the search criteria in the website) are especially interesting data since most provincial coins lack clear marks of value. Provincial denomination systems are therefore notoriously difficult to establish. What does become instantly clear is the enormous diversity of weight standards and denomination, sometimes within limited regions.

The published RPC volumes also regularly discuss circulation, although this is even more difficult than debasement to study through a catalogue that focuses on types rather than individual coins, and on place of minting rather than findspot.Footnote 35 Circulation is an important issue for provincial coins, which often circulated for extended periods of time. This is indicated by the amount of wear and by the inclusion in single hoards of coins that were issued centuries apart. It is a logical consequence of the fact that most cities issued coins only intermittently: something that can be traced on the website by selecting individual cities or regions, and then looking at date ranges. One result was that coins were frequently countermarked, to clarify or reaffirm the status of a worn coin, or to ‘appropriate’ coins struck by other cities. The latter seems to have been the case when the city of Aphrodisias countermarked coins from a range of cities by imprinting them with a small cult statue of Aphrodite.Footnote 36

IV ROMAN COINS AND ROMAN HOARDS

The usefulness of the RPC project for the Roman historian must by now be clear. Yet it is not without its difficulties. It is, by design, a standard typology. It therefore counts types, not coins. And it shows where coins were minted, not where they were found. So it is difficult to apply the material to questions of distribution and circulation. The only volume to escape these problems somewhat is RPC VII.1, which provides a full catalogue for its period and area. Yet this volume only discusses a single area for a period of six years. And even RPC VII.1 follows the organising principle of the project as a whole, by conventus (i.e. juridical districts). It is wholly understandable (and even recommendable) that RPC organises coin types systematically, and wants to be editorially consistent. However, the choice for conventus as central geographical unit is somewhat arbitrary — with, for instance, die-sharing taking place between cities belonging to different conventus.Footnote 37

These problems are now overcome by a recent (digital) numismatic project which should further ensure the systematic inclusion of Roman coins in historical analysis. The Coin Hoards of the Roman Empire (CHRE) project (https://chre.ashmus.ox.ac.uk/) started in 2013 with the massive ambition of collecting relevant information about all hoards containing coinage in use in the Roman Empire between 30 b.c. and a.d. 400. They defined a hoard as ‘any group of coins which appears to have been deposited together’. This ranges from several denarii found together (or even single gold coins) to the largest uncovered hoard: the Misrata hoard (Libya) with over 108,000 coins.

The scale of the results is staggering. In the first five years of the project, summary records for 12,144 hoards and single gold coins were placed online, bringing together approximately 3.5 million coins. The project is now in its second phase (2019–23), in which the goal is to complete geographical coverage, including Roman hoards which are found outside the Empire (Fig. 4). Moreover, the project now systematically records at coin level, including full description of single coins and their RIC or RPC number. The most recent count of material in CHRE stands at 16,400 hoards and single gold finds comprising over 6 million coins from inside and outside the Roman Empire.

FIG. 4. Distribution of coins in CHRE database by findspot.

Needless to say, this is a heavily collaborative effort, with a large number of people (including many volunteers throughout the world) responsible for entering the material, which then needs validating. The project is run by Chris Howgego and Andrew Wilson with support from Cristian Gazdac and Marguerite Spoerri Butcher (who was responsible for RPC VII.1). It is exemplary in the way it has joined forces with international organisations, scholars and graduate students.Footnote 38 Not all areas are equally well represented, though, and not all partners are equally active. Moreover, not all countries have systems equivalent to the Portable Antiquities Scheme, which means that coverage is uneven, with material from the UK, France, the Netherlands and Romania heavily overrepresented at the cost of, especially, Turkey, Greece and North African countries. Still, the amount of available data is extremely impressive and growing.

A first edited volume, based on a conference bringing together the main scholars involved in the project, is imminent and illustrates the range of themes and questions that can be addressed through this assembly of hoard data, with obvious attention to patterns of circulation and monetary reforms.Footnote 39 A second conference on ‘Crossing Frontiers: the Evidence of Roman Coin Hoards’ took place in April 2022. Since the summer of 2020, moreover, the CHRE website makes it possible to search at the level of individual coins. These can be searched by period, person, reign, denomination, material, mint, or aspect (such as banker's marks, hybrid, gilded or clipped). Results can be mapped on terrain maps and on imperium maps supplied by the Digital Atlas of the Roman Empire (https://dh.gu.se/dare/), and all hoard locations have been matched with the relevant Pleiades entries (https://pleiades.stoa.org). This allows, for instance, for instant mapping of all the locations at which coins were found, including a great many outside the borders of the empire (Fig. 4).

It also makes it possible to look at the distribution of coins from individual mints. It is only a couple of minutes’ work to find that the current material includes 4,384 coins that were minted in Alexandria, 3,997 of which are included with precise coordinates, so that they can be accurately mapped, generating the map in Fig. 5.

FIG. 5. Distribution of Alexandrian coins in CHRE database by findspot.

The pattern is skewed by local coverage and the presence of large hoards. It is also limited to data that has been validated, which explains the void in Egypt. The fact that there are more Alexandrian coins found in the Balkan and north-western provinces of the Empire than in Asia Minor probably tells us more about regional variation in the discovery and documentation of Roman coins than the original distribution. But that does not take away from the surprisingly wide circulation of Alexandrian coins on the basis of what has been documented. Looking at the distribution of coins, geographically and chronologically, has even helped to date moments of local violence more accurately.Footnote 40

At a practical level, all search results, and also the make-up of whole hoards like the Misrata one (or the Reka Devnia hoard of 81,000 coins), can be downloaded as CSV files, allowing for easy further analysis. Finally, CHRE provides a database of over 4,000 relevant items of bibliographic references which can be searched by author, title, year and type of publication. Too much research into Roman history still underappreciates coins as source material. This is at least partly because numismatic research can look daunting, and is still often inward-looking. Yet coins provide extremely valuable insights into how the Roman Empire functioned. They were continuously issued in large numbers and combine text and image. Thirty years ago, Chris Howgego ended his JRS review of RPC I with the conclusion that ‘there can now be no excuse for ignorance of the content of Roman provincial coinage, or for failure to appreciate its value as an historical source’.Footnote 41 Now, with RPC and CHRE readily available online, there really is no excuse any more.