Trust is central to the relationship between doctor and patient. An important skill in psychiatry therefore is the ability to relate to and effectively treat patients in whom the capacity for trust is diminished as a consequence of psychopathology. The focus of this article is paranoid personality disorder, a condition in which mistrust of other people is the cardinal feature. It is not an uncommon disorder, with a prevalence in community samples of around 1.3% (Reference Torgersen, Oldham, Skodol and BenderTorgersen 2005), rising to up to 10% in psychiatric out-patient samples (Reference Bernstein, Useda and SieverBernstein 1993). Despite this, the research base on the disorder remains relatively sparse (Reference Bernstein, Useda, O'Donohue, Fowler and LilienfieldBernstein 2007).

Diagnosis

Clarifying the diagnosis of a patient with paranoid thinking is an essential first step to management, with ramifications for prognosis, treatment and medicolegal issues such as involuntary treatment or criminal responsibility. The DSM–IV–TR criteria for paranoid personality disorder (American Psychiatric Association 2000) have been criticised for underrepresenting the typical affective and interpersonal features of the disorder, features that give a richer sense of the typical presentation (Reference Bernstein, Useda, O'Donohue, Fowler and LilienfieldBernstein 2007) (Box 1).

Box 1 Paranoid personality disorder: DSM v. Berstein

| DSM–IV criteria (summarised) | Primary traits identified by Berstein (2007) |

|---|---|

|

|

As with all personality disorders, diagnosis is dependent on longitudinal evidence that mal-adaptive features of feeling, thinking and behaving are enduring over time. Collateral data are thus essential to demonstrate that the features are not confined to particular situations (such as clinical encounters) and that they have been in evidence since adolescence or early adulthood.

The most likely differential diagnoses are as follows.

Normality

A normal response to unusual circumstances should always be considered as part of the differential diagnosis of a patient with cross-sectional features suggestive of paranoid personality disorder. Features of personality disorders in general can be considered as extreme, maladaptive variants of normal traits (Reference Widiger, Frances, Costa and WidigerWidiger 2002). Dimensional rather than categorical analysis seems especially applicable to paranoid thinking: ‘one person's paranoia is another's due caution, and one person's trust is another's gullibility … normal development entails learning that “not everyone who seems trustworthy is trustworthy” ’ (Reference Blaney, Millon, Blaney and DavisBlaney 1999: p. 343). Suspiciousness may be adaptive in certain environments, and determining how much interpersonal trust is appropriate in a given situation may indeed be a ‘vexing judgemental dilemma’ (Reference KramerKramer 1998). Members of minority groups in particular may show defensive thinking that is understandable in the broader social context rather than being indicative of mental disorder (see later).

An epidemiological study of a community sample in New Zealand found that 12.6% demonstrated at least some paranoid features (Reference Poulton, Caspi and MoffittPoulton 2000), and nearly half of American college students report experiences of paranoid thinking (Reference Ellett, Lopes and ChadwickEllett 2003). Thus, many people manifest mistrust and suspicion from time to time but because they are transient, modifiable and not significantly disruptive, such phenomena are not pathological.

Clinically significant paranoid thinking may therefore best be conceptualised as an over-generalised form of a common and adaptive psychological process which, in its normal form, has some evolutionary value by facilitating the detection of threats to the self by other people. Conceptual models that emphasise continuity (although not equivalence) with normality may be helpful when attempting to engage people with paranoid personality disorder in treatment.

Other personality disorders

People with other personality disorders may show clinical features that superficially resemble those of paranoid personality disorder.

Schizoid personality disorder

Schizoid personality disorder is characterised by social withdrawal. However, individuals with the disorder are indifferent to other people, not desiring interpersonal contact, rather than being suspicious of them, as in paranoid personality disorder.

Schizotypal personality disorder

This disorder is characterised by a degree of suspiciousness of other people, but also involves distinct oddities of belief and thinking quite different from those seen in paranoid personality disorder.

Avoidant personality disorder

As with paranoid personality disorder, avoidant personality disorder is characterised by a degree of mistrust of other people and consequent social withdrawal, the difference being that the avoidant person is much less ready to see malevolence in other people; their problem is that they lack confidence and believe that they themselves will perform inadequately in social situations.

Narcissistic personality disorder

Narcissistic personality disorder is characterised by an overly inflated sense of entitlement and grandiosity. Generally, there is preoccupation with the need for praise rather than overwhelming suspiciousness of others' intent, although paranoid features redolent of paranoid personality disorder may emerge under stress (Reference Young, Klosko and WeishaarYoung 2003).

Antisocial personality disorder

The key characteristic of antisocial personality disorder is recurrent transgression of others' rights. Individuals with paranoid personality disorder may harm others as part of what they view as revenge or even as a pre-emptive strike. It may be difficult, however, to distinguish the post hoc rationalisations of antisocial individuals for their interpersonally harmful behaviours from genuinely paranoid thinking about the malevolent intent of the victims.

Borderline personality disorder

People with borderline personality disorder may develop stress-related paranoid ideation and anger, but, unlike in paranoid personality disorder, these are not enduring features.

Comorbid disorders

Comorbidity of paranoid personality disorder with other personality pathology is common, occurring in more than half of cases (Reference Widiger, Trull, Widiger, Frances and PincusWidiger 1998). In forensic populations, antisocial personality disorder is commonly comorbid with paranoid personality disorder (Reference Blackburn and CoidBlackburn 1999).

Social anxiety

Paranoid personality disorder may initially present with anxiety complaints but careful mental state examination will reveal the underlying paranoid core features. There is some overlap with anxiety disorders such as social phobia and social anxiety: both may entail social withdrawal and concerns about others' evaluation of the self. The crucial distinction is that in paranoid personality disorder there is a perception of planned harm to self by malevolent others, not merely a preoccupation with negative events in the future or with exposure to public scrutiny. Comorbidity may occur: one study (Reference Reich and BraginskyReich 1994) suggests that over half of those with paranoid personality disorder also suffer from panic disorder.

Depression

There is a complex relationship between mood and paranoid thinking. Depressive disorders may present with paranoid symptomatology, often with the underlying theme that the persecution by others is in some way deserved: so-called ‘bad-me paranoia’ (Reference Chadwick, Trower and Juusti-ButlerChadwick 2005). A careful longitudinal history will distinguish the disorders; if clear symptoms and signs of a depressive illness are present then these need to be vigorously treated before a diagnosis of paranoid personality disorder can be made with any confidence.

Delusional disorder

In practice, delusional disorder generally the most problematic differential diagnosis. By definition, people with paranoid personality disorder do not display persistent psychotic symptoms, whereas delusional disorder is a condition characterised by persistent non-bizarre delusions in the absence of other features of a psychotic illness. This distinction, however, merely begs the question of how to distinguish delusions from the intensely held, idiosyncratic (sometimes called ‘overvalued’) ideas of a person with paranoid personality disorder. One key distinction is the degree to which reality testing is impaired: in paranoid personality disorder, individuals can at least entertain the possibility that their suspicions are unfounded or that they are overreacting, whereas a diagnosis of delusional disorder is likely warranted when beliefs of persecution are held with incorrigible conviction, resulting in extensive effects on behaviour (Reference Skodol, Oldham, Skodol and BenderSkodol 2005). To further complicate the issue, delusional disorder may emerge gradually or it may be associated with a precipitating stressful event against a background of a vulnerable paranoid personality, although this is by no means always the case (Reference Blaney, Millon, Blaney and DavisBlaney 1999).

In practice, mental health clinicians often disagree about specific cases, and the reliability with which individuals manifesting paranoid behaviour can be differentially classified has not been empirically determined (Reference HaynesHaynes 1986). Genetic studies have similarly been unable to disentangle delusional disorder from paranoid personality disorder (Reference WinokurWinokur 1985), although it now appears that both disorders are probably genetically distinct from schizophrenia (Reference Asarnow, Nuechterlein and FogelsonAsarnow 2001; Reference Cardno and McguffinCardno 2006).

This diagnostic problem can be viewed as part of a wider debate about the boundaries of psychosis, and the resurgent idea that psychotic symptoms are best conceptualised as dimensional phenomena on continua with normal experiences (Reference Claridge and ClaridgeClaridge 1997; Reference van Os, Hanssen and Bijlvan Os 2000; Reference Bentall and TaylorBentall 2006). In his classic paper, Reference StraussStrauss (1969) suggested four criteria for determining the threshold into clinical psychotic illness:

-

• degree of conviction regarding the objective reality of the unusual experience

-

• degree to which a cultural or stimulus determination of the experience is absent

-

• amount of time spent preoccupied with the experience

-

• implausibility of the experience.

Others (Reference Claridge and ClaridgeClaridge 1997) have emphasised that the key distinction is not simply the level of symptoms but rather their effect on day-to-day coping abilities, i.e. the functional impairment they cause.

The distinction is challenging and is of more than mere academic interest, having clear clinical implications. Except at times of severe decompensation, people with personality disorders are generally not appropriate candidates for coercive treatment nor, if their behaviour leads to offending, do they generally qualify for consideration of a criminal defence based on lack of criminal responsibility. Those diagnosed with delusional disorder, however, may be candidates for involuntary treatment and may be considered as lacking criminal responsibility should they offend as a result of their disorder (Reference Bronitt, Mcsherry, Bronitt and McSherryBronitt 2005).

Although this differential diagnosis will never be easy, the distinction will be assisted by a carefully documented history and chronology of the development of the patient's paranoid thinking, as well as a careful mental state examination.

Other psychotic illnesses

Schizophrenic illnesses must be considered in the differential diagnosis of paranoid personality disorder; the presence of persisting psychotic symptoms and other features of schizophrenia will generally make this differential clear. Other psychotic illnesses that may present with paranoid features include:

-

• chronic organic psychoses such as those developing in the wake of dementia;

-

• substance-induced psychoses: beware, however, that individuals with paranoid personality disorder may well also misuse substances and develop such disorders;

-

• brief reactive psychoses secondary to acute stressors (Reference Munro and MunroMunro 1999): again, comorbidity may occur and a paranoid personality disorder may confer vulnerability to such brief psychotic episodes (Reference Miller, Useda, Trull, Adams and SutkerMiller 2001), particularly in the context of acute stress such as drastic environmental change (e.g. imprisonment, migration, induction to the military).

(See Key points 1.)

Psychological processes

An understanding of paranoid thinking and behaviour in general can assist the clinician in understanding and treating the patient with paranoid personality disorder. Although most proposed models have focused on a single specific process, in reality it seems likely that multiple cognitive, behavioural and social processes are usually involved, and these interact and become mutually reinforcing. Thus, the mechanisms discussed below (based on studies involving participants with a variety of paranoid disorders) should not be viewed as exclusive, competing theories but rather as descriptions of various possible alternative pathways to paranoia, the relative importance of each varying between and within individuals over time.

Cognitive biases

People with high levels of paranoid thinking have an externalising, personal attributional bias: a tendency to explain negative events in their life by blaming others rather than reflecting on their own potential contribution to circumstances (Reference Bentall, Corcoran and HowardBentall 2001, Reference Bentall and Taylor2006). The normal self-serving bias, whereby negative events are attributed to external circumstances, is exaggerated and distorted (Reference Campbell and SedikidesCampbell 1999), being skewed towards other people and their supposed malevolent intent. There is a corresponding tendency to underuse contextual information when explaining negative outcomes (Reference Gilbert, Pelham and KrullGilbert 1988).

Reference Bentall and TaylorBentall (2006) suggests that this attributional bias is a psychological defence against underlying low self-esteem, activated when there is perceived threat to the individual's positive view of themselves. Although there is some evidence that self-esteem is generally low in individuals with paranoia in both clinical (Reference Garety and FreemanGarety 1999) and non-clinical samples (Reference Martin and PennMartin 2001; Reference Ellett, Lopes and ChadwickEllett 2003; Reference Combs and PennCombs 2004), the relationship between self-esteem, paranoid thinking and behaviour is complex. As mentioned earlier, there is evidence, for example, of subgroups with particularly low self-esteem and low mood who feel the perceived persecution to be justified – ‘bad-me paranoia’ (Reference Chadwick, Trower and Juusti-ButlerChadwick 2005). In such cases it may be that the supposed defence of external attribution of blame is only partially successful in warding off depressive feelings.

Information processing factors

In general, attributions that invoke contextual, situational factors require more information and more cognitive resources than external, personal attributions. As cognitive load increases, people tend to use external, personal, ‘paranoid’ attributions as a kind of default option (Reference Gilbert, Pelham and KrullGilbert 1988). This may relate to the mooted association between paranoid disorders and brain damage (Reference MunroMunro 1988). Similarly, perceptual deficits that reduce the availability of relevant social information, most notably in the realm of impaired hearing, have long been associated with increased risk of paranoid thinking (Reference Thewissen, Myin-Germeys and BentallThewissen 2005).

More subtle functional impairments that affect social skills have been linked to paranoia. Deficits in emotional and social perception tasks have been associated with social anxiety and subclinical paranoia (Reference Combs and PennCombs 2004). Paranoid thinking has also been linked to deficits in ‘theory of mind’: the ability to understand the intentions and mental states of others (Reference Kinderman, Dunbar and BentallKinderman 1998). This may contribute to difficulties in constructing situational (as opposed to personal) attributions for negative social interactions, since failure to understand the viewpoint of another person may encourage personal attributions. For example, if a colleague passes a person in the street without greeting them, a failure to understand that the colleague may, for example, have been distracted by worry (a situational attribution) may encourage the personal attribution that the colleague is rude.

The hypervigilance of individuals with paranoia appears to be related to an attentional bias whereby they are more likely to both notice and remember (and hence ruminate on) threat-related information, a processing bias that has been demonstrated in both clinical (Reference Garety and FreemanGarety 1999) and non-clinical (Reference Combs and PennCombs 2004) populations.

Interpersonal processes

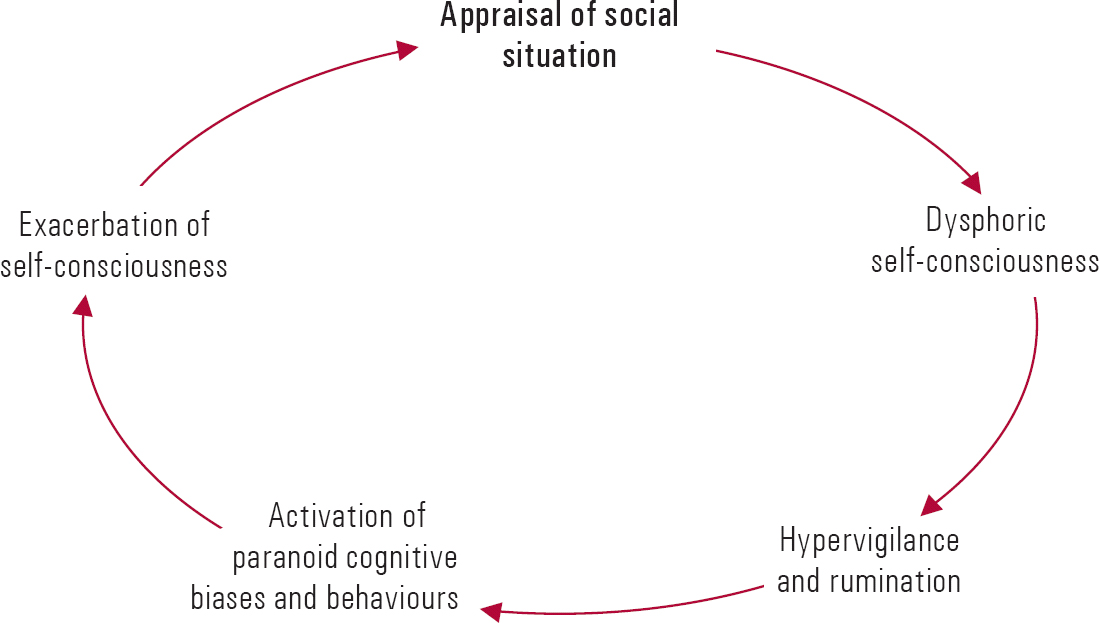

In ‘normal’ populations, certain kinds of social situation appear to encourage paranoid thinking. Such situations are likely to severely exacerbate the pathological behaviour and thinking of those with pre-existing paranoid personality traits. A model based on a review of such social effects (Reference KramerKramer 1998) proposes that particular social situations are more likely to be appraised in such a way as to lead to ‘dysphoric self-consciousness’; this in turn leads to hypervigilance and rumination, and activation of paranoid cognitive biases and behaviours. These may exacerbate the feelings of self-consciousness, and hence feed a vicious cycle (Fig. 1). Specific situations that predispose to such cycles include:

FIG 1 The cycle of dysphoric self-consciousness (Reference KramerKramer 1998).

-

• feeling different from the rest of the social group, for example because of gender, race or level of experience

-

• feeling under the evaluative scrutiny of other people with more power, for example professional seniors

-

• a sense of uncertainty regarding social status, for example when new to a group.

Similarly, others (Reference Mirowsky and RossMirowsky 1983; Reference HaynesHaynes 1986) have emphasised that paranoid thinking is likely to emerge in situations involving:

-

• sudden social loss or isolation

-

• acute disruption of usual social networks

-

• exposure to environments in which previous social skills may not be useful, for example immigration or imprisonment

-

• acute sensory deficits

-

• actual powerlessness and victimisation.

Paranoid personality disorder, by definition, implies enduring features that will be evident even in the absence of such circumstances. However, an understanding of how paranoid thinking can be engendered by such situations not only helps to predict when the features of paranoid personality disorder are likely to become more apparent, but also assists in the differential diagnosis between paranoid personality disorder and normal responses to extraordinary circumstances.

The spiral of escalating paranoia

These various cognitive, behavioural and social processes may become mutually reinforcing, leading to malignant spirals of escalating paranoia. Such processes can make therapeutic change particularly difficult to effect.

The following self-perpetuating processes are commonly active in those with paranoid personality disorder.

-

• It is generally possible to find evidence of malign intent in at least some people some of the time: this is readily taken as confirmatory evidence that the person was ‘right all along’ to be suspicious.

-

• Conversely, if others' behaviour is apparently benign, this can be interpreted as a ‘front’ or as ‘trickery’.

-

• It is logically impossible to prove a negative, for example for a spouse to prove that he or she is not having an affair. The very absence of evidence can be interpreted as confirmation of a ‘cover up’.

-

• People with paranoid personality disorder are generally socially withdrawn, and when they engage in interpersonal encounters they show a tendency to be hypervigilant and suspicious. This may put others off approaching someone with the disorder and may even cause them to be hostile and exclusionary of that person. Such scenarios may confirm the person's suspicions and exacerbate their isolation – a self-fulfilling prophecy termed ‘reciprocal determinism’ (Reference HaynesHaynes 1986). This dynamic can be seen in querulant, persistent complainers, who become increasingly unreasonable in their dealings with organisations and generally elicit progressively more hostile and negative treatment from those in authority (Reference Mullen and LesterMullen 2006).

-

• Persistent social withdrawal disrupts social feedback and hence there may be few challenges to the world-view of someone with paranoia: it is difficult to learn from experience that people can be trusted if interpersonal experiences simply never occur.

Hence, paranoid thinking and behaviour can be remarkably resistant to change – a self-sustaining, self-defeating cycle (Reference KramerKramer 1998).

The risk of violence

In light of their tendency to view others' actions as hostile, it would appear obvious that people with paranoid personality disorder would be at increased risk of interpersonal violence. Most research data derives from samples with paranoid features that often fall short of a diagnosable para1noid personality disorder and are generally present in combination with other significant risk factors. Hence, although there is convergent evidence that paranoid traits do indeed increase risk of violence, it should not be assumed that an individual with paranoid personality disorder is necessarily at high risk of such behaviour.

In cross-sectional studies, paranoid personality features have been associated with histories of both violent (Reference MojtabaiMojtabai 2006) and antisocial behaviours in general (Reference Berman, Fallon and CoccaroBerman 1998), even when antisocial and borderline pathology is statistically controlled for. Similarly, high levels of delinquency in teenagers have been associated with paranoid features such as feeling mistreated, victimised, betrayed and the target of false rumours (Reference Krueger, Schmutte and CaspiKrueger 1994). A large American longitudinal study (Reference Johnson, Cohen and SmailesJohnson 2000) found that paranoid traits in adolescence predicted violence and criminal behaviour in later adolescence and early adulthood, even after controlling for various possible confounding variables.

In non-clinical populations, a meta-analysis (Reference Bettencourt, Talley and BenjaminBettencourt 2006) concluded that the personality feature of high rumination, which would be expected in paranoid personality disorder, is associated with a tendency to aggressive behaviour, but only under provoking conditions. This suggests that violence in people with paranoid features generally requires some level of provocation. Note, however, that owing to their various distortions in thinking and perceiving, their threshold for feeling provoked may be abnormally low; another study (Reference Johnson, Cohen and SmailesJohnson 2000) found that paranoid symptoms were associated with initiating physical fights. There is also ample evidence that specific suspicions about the fidelity of intimate partners, commonly seen as a feature of paranoid personality disorder, are associated with an increased risk of threatening and initiating violence against the partner and others (Reference MullenMullen 1995).

Pathways to violence in paranoia

There are various possible explanations for the increased risk of violence in those displaying paranoid thinking. Contemporary models of aggression (Reference Anderson and BushmanAnderson 2002) emphasise the role of biases in cognitive processing, affect-regulation and social information processing. Those with paranoid biases tend to perceive situations to be more provocative than is warranted and to view the world as hostile and threatening; their often fragile self-esteem and their sensitivity to social status may render them hypersensitive to perceived challenges to status as well as to personal safety. Hence, an individual with paranoia may be motivated to engage in both retaliatory and pre-emptive violent strikes on others (Reference Berman, Fallon and CoccaroBerman 1998). They are also likely to be both highly suspicious and unforgiving of perceived attacks, tending to ruminate on past transgressions by others; such tendencies to bear grudges may also increase their risk of violence. In addition, the ‘malignant spiral’ discussed earlier, whereby hostility is readily evoked in others by the suspicious, odd behaviour of people with paranoia, may well increase the likelihood that they will encounter actual hostile behaviour from others, which in turn would further increase the likelihood of aggression.

Comorbid disorders are of particular importance when assessing and managing the risk of violence in an individual with paranoia. The combination of a paranoid tendency to see others as threatening with low internal constraints against violence (for example as part of an antisocial personality structure) is particularly concerning (Reference Blackburn and CoidBlackburn 1999). Similar considerations may apply when acute mental illness supervenes in paranoid personality disorder, resulting in lowered inhibitory thresholds for violent behaviour because of psychotic, mood or anxiety symptoms (Reference Kennedy, Kemp and DyerKennedy 1992; Reference Buchanan, Reed and WesselyBuchanan 1993; Reference TaylorTaylor 1998; Reference Hodgins, Hiscoke and FreeseHodgins 2003).

As well as violence, paranoid personality features have been associated with other problem behaviours, including stalking (Reference Mullen, Pathe and PurcellMullen 2000), the uttering of threats (Reference MacDonaldMacDonald 1963) and abnormal complaining behaviours (Reference Mullen and LesterMullen 2006).

(See Key points 2.)

Treatment of paranoid personality disorder

None of the possible treatments for paranoid personality disorder has been subjected to randomised control trials. Notwithstanding this, the condition should not be viewed as untreatable and there is a degree of consensus with respect to general principles when attempting to safely manage the disorder (Reference Gabbard and GabbardGabbard 2000; Reference FaginFagin 2004).

General principles

Differential diagnosis and comorbidity

As discussed above, diagnostic formulation, including consideration of comorbid personality pathology and/or mental illness, is critical in understanding and managing paranoid personality disorder.

Treatment aims

Appropriate long-term treatment goals (Reference Bernstein, Useda, O'Donohue, Fowler and LilienfieldBernstein 2007) include helping the patient to:

-

• recognise and accept their own feelings of vulnerability

-

• increase their feelings of self-worth

-

• develop a more trusting view of others

-

• verbalise their distress, rather than use counterproductive strategies such as shunning or intimidating others.

As with all personality disorders, progress is likely to be slow – some suggest that at least 12 months may be required before determining whether treatment is effective (Reference Bateman and TyrerBateman 2004).

Countertransference

Patients with paranoid personality disorder are likely to engender strong countertransference feelings of defensiveness and even aggression in the clinician. Clinicians should avoid reactive counterattacks, which will probably result in disengagement or even violence. Conversely, they should also beware of minimising the risk of violence because of over-optimism or simple denial, particularly with female patients. They should be open and firm when necessary, and explain why particular decisions have been made, particularly decisions that may be unwelcome. Resistance should be expected.

Sensitivity to rejection and to authority

Patients with paranoid features are likely to be brought to treatment by others rather than referring themselves. Coercive treatment is generally neither ethically nor legally justified in the absence of comorbid mental illness. It is possible to engage those with paranoid personality disorder in meaningful treatment but a forceful or duplicitous approach is unlikely to bear fruit. The clinician should avoid arousing suspicion: for example, the patient should be informed if contact occurs between different clinicians involved in their care. The source of information contained in the file (whether it is derived from the patient or someone else) should be clearly stated. It is important to help the patient to save face and feel that they have some control over their life and their treatment.

Boundary management

Paranoid individuals may be particularly prone to misunderstand a clinician's acts of kindness or words of encouragement as a cover for more malevolent intentions. An overly ‘warm’ therapeutic style is therefore not indicated. Close physical contact, or even overly close seating, should be avoided. An individual with paranoia is likely to require more than the usual amount of body space. In general, group therapy should be avoided (Reference Gabbard and GabbardGabbard 2000).

Mood symptoms

The clinician should be alert to changes in the patient's mood. For patients who successfully engage in treatment, an understandable sadness (and possibly suicide risk) may emerge as they develop insight into how their paranoid behaviours have isolated them. Antidepressant medication should be considered if there is clinical evidence of an emergent depressive illness.

Psychotherapy

Psychosocial residential treatment with psychotherapy may bring about long-term gains in functioning for individuals with severe personality disorders, including those with paranoid features (Reference Chiesa and FonagyChiesa 2003). Individual supportive dynamic psychotherapy (Reference Gabbard and GabbardGabbard 2000) and schema therapy (Reference Young, Klosko and WeishaarYoung 2003) have also been advocated for paranoid personality disorder.

Possibly the most useful for the general psychiatrist, however, is Beck and colleagues' model of cognitive therapy for paranoid personality disorder (Reference Beck, Freeman, Davis, Beck, Freeman and DavisBeck 2004). The basic tenet is that clinical paranoia can be construed as a systematised and overgeneralised form of an ordinary adaptive psychological process. The core cognitive schema is posited to concern feelings of inadequacy, and so the initial aim of such therapy is to enhance the individual's sense of self-efficacy, while openly accepting that they will be mistrusting of clinical intervention, particularly in the early stages. In parallel with this, social skills such as assertion, communication and empathy can also be enhanced. In the longer term, the tendency to attribute blame is challenged and modified, with the aim of terminating the malignant spirals involved. Specific targets therefore might include the beliefs that other people are always malicious and deceptive, or that it is necessary to be constantly on the look out for threats. The technique of ‘collaborative empiricism’, whereby therapist and patient jointly examine the patient's beliefs in the light of objective evidence, may be useful. In this process, the possibility that the patient's suspicions regarding others may contain a kernel of truth should be acknowledged if appropriate (Reference Bernstein, Useda, O'Donohue, Fowler and LilienfieldBernstein 2007).

Pharmacotherapy

The role of pharmacotherapy in pure paranoid personality disorder is not well established. If such disorders are viewed as existing on a spectrum with a delusional disorder (Reference Kendler and GruenbergKendler 1982) then it might be reasonable to try an antipsychotic medication (Reference Grossman and MagnavitaGrossman 2004). However, no such medications are currently formally licensed for this indication.

Obviously, comorbid conditions such as depression and anxiety disorders, or emerging psychotic illnesses, may require appropriate medication.

(See Key points 3.)

Conclusions

A certain degree of suspiciousness with respect to the intentions of others is normal, particularly in certain social situations. However, such thinking may be maladaptive and pathological in extent. Paranoid features are found in a whole variety of contexts: in previously healthy individuals subjected to abnormal stress; in mental illness; and in those with personality disorders, most notably in paranoid personality disorder. Although empirical data regarding paranoid personality disorder are limited, an understanding of underlying psychological processes and adherence to certain management principles can assist psychiatrists in assessing and treating this challenging and disabling condition.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None.

MCQs

-

1 The following features are not consistent with a diagnosis of pure paranoid personality disorder:

-

a persistent questioning of an intimate partner about their activities

-

b rumination about a co-worker's attempt to embarrass the patient 2 years ago

-

c a restricted affective range in clinical encounters

-

d a belief that a neighbour has been repeatedly breaking into the patient's house and put an odourless poison in his fruit

-

e an impoverished social life.

-

-

2 The self-serving attributional bias:

-

a is usually pathological

-

b is exaggerated in paranoid personality disorder

-

c refers to a tendency to meet one's own physiological needs before those of others

-

d refers to a tendency to attribute positive events to external circumstances

-

e is absent in paranoid disorders.

-

-

3 The following have not been related to an increased likelihood of paranoid thinking:

-

a deafness

-

b deficient theory of mind

-

c being a new university student

-

d being a recent immigrant

-

e having good social supports.

-

-

4 Accepted treatments for uncomplicated paranoid personality disorder include:

-

a cognitive therapy

-

b electroconvulsive therapy

-

c involuntary medication with injectable antipsychotic agents

-

d group therapy

-

e anxiolytics.

-

-

5 When working with paranoid personality disorder patients, it is useful to:

-

a adopt a warm therapeutic style

-

b disclose personal details about one's own life

-

c scrupulously avoid suggesting that their concerns about others might have any basis in reality

-

d firmly insist that the patient accept medication

-

e engage in ‘collaborative empiricism’.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | f | a | f | a | f | a | t | a | f |

| b | f | b | t | b | f | b | f | b | f |

| c | f | c | f | c | f | c | f | c | f |

| d | t | d | f | d | f | d | f | d | f |

| e | f | e | f | e | t | e | f | e | t |

KEY POINTS 1 The most likely differential diagnoses

|

|

|

KEY POINTS 2 The processes of paranoia

|

KEY POINTS 3 Treatment of paranoid personality disorder

General principles for the clinician

|

Psychotherapy

|

Pharmacotherapy

|

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.