The grey old man in the corner

Of his father heard a story,

Which from his father he had heard,

And after him I have remembered.Footnote 1

These words, the closing lines of the 1861 published version of the Llyn y Fan Fach legend, encapsulate the permanence of, and enduring fascination with, this ancient folktale. Since its earliest formulation many centuries ago, and through countless variations as a result of oral transmission from one generation to the next, the story of the Welsh ‘Lady of the Lake’ – a tale which also explains the origins of the Physicians of Myddfai – has continued to enthral and animate human imaginations through to the present day. According to Sioned Davies, the story is ‘one of the most popular of all Welsh legends and is to be found in almost every collection of Welsh folktales’;Footnote 2 and for Juliette Wood, the legend ‘somehow seems so typically Welsh with its otherworld fairy bride, poignant sense of lost love, and its doctor-magician sons’.Footnote 3 The Doctor of Myddfai, a collaboration between Peter Maxwell Davies and David Pountney, is one of many creative reimaginings of this famous Welsh folktale. The work, Davies's third large-scale opera, composed in 1995, occupies an important position within the composer's output for the opera house and theatre. However, whereas a significant amount of scholarly attention has been afforded to Davies's music-theatre works of the 1960s, such as Eight Songs for a Mad King (1969), and the first two full-scale operas, Taverner (1962–8) and Resurrection (1986–7), The Doctor of Myddfai has been somewhat neglected in the literature by comparison.Footnote 4

One of the main reasons for this neglect is perhaps connected to the widely held opinion that Davies's works from the 1980s onwards – a period in which he was composing (among many other works) symphonies, concertos and string quartetsFootnote 5 – are in some way more ‘mainstream’ and conservative, and therefore less worthy of attention, than the more radical works of his earlier period – a group of compositions which should also include Resurrection, which despite its completion date was started in 1963.Footnote 6 However, I would argue that this viewpoint is unhelpfully reductive and unjustly dismissive of the later works, the majority of which are highly stimulating and powerful musical statements that invite close, detailed scrutiny.Footnote 7 This is certainly the case with The Doctor of Myddfai. Two additional factors make this work significant in relation to the composer's overall dramatic output: firstly, as will be discussed below, many dramatic themes in the opera have their origins in his earlier music-theatre works, operas and chamber operas; and secondly, given that the work completed a ‘trinity’ of large-scale operas, it seems highly likely that it held a personal significance for the composer, especially if one takes into account the following comment taken from Davies's private journal of 1974:

(I remember, in a moment of insight ten or more years ago, seeing a lifetime's work of 3 operas, Taverner, Resurrection, and a third one seen/heard from afar, taking place in something akin to, if not actually in, an enclosed order, in a musical condition of ever expanding & intensifying CONTEMPLATIO)Footnote 8

Previous commentary on The Doctor of Myddfai has been published in two distinct formats: reviews for newspapers and journals, mostly clustered around the first performances of the work in 1996 and the release of the Collins Classics recording in 1998; and isolated references within various journal articles and book chapters, ranging from brief mentions to more general discussions. This article, therefore, is the first in-depth study of this work and brings new insights to the discussion of a major British opera of the late twentieth century. Drawing on a body of primary source material, including Davies's sketches for the work and his own unpublished private journals,Footnote 9 this article will examine the opera from two perspectives: the first explores the work's dystopian setting, particularly in relation to political concerns and environmental anxieties; the second focuses on the opera's articulation of Welsh identity, particularly through the use of Welsh folklore, native landscape and place, and indigenous musical signifiers. The intersection of these two elements – the work's celebration of Welshness and its dystopian qualities – imbues the opera with an intrinsic yet highly productive sense of tension and opposition. These characteristics are assimilated into both the libretto and the music and contrive to propel the narrative forward to its compelling conclusion.

The Llyn y Fan Fach folktale and the Physicians of Myddfai

The Llyn y Fan Fach folktale belongs to the supernatural legend tradition in which an ‘otherworld woman marries a mortal, but eventually returns to her world leaving him and their children’.Footnote 10 According to Juliette Wood, about three dozen variants of this ‘fairy bride’ legend exist in Wales alone, ranging from the tenth to the twentieth century.Footnote 11 But the tradition is also widespread in northern and western European countries where the woman is sometimes in animal form, such as a seal, and in other versions a mermaid.Footnote 12 In Wales, however, ‘she appears in human form and her return is motivated by the violation of some taboo’.Footnote 13 In the Llyn y Fan Fach legend, the taboo is a specific condition of the marriage: namely, that the bride must not receive three causeless blows from her husband. In the tale, the lake is used as an entrance or gateway to the supernatural world.Footnote 14 By bringing humans into contact with the liminal otherworld, and by making a taboo a central part of the narrative, the story moves beyond the realms of the supernatural and into the anthropocentric world, where the character of the husband is tested, including the ways in which he reacts when he encounters difference – a difference that is both attractive and dangerous. But place and cultural specifics are important to the meanings of this story, too. The tale is rooted in Myddfai, Carmarthenshire, and its surrounding areas, and mentions specific locations: the lake itself, Llyn y Fan Fach (‘lake of the small hill’ – see Figure 1); Blaensawdde, near Llanddeusant (the hamlet in which the man and his mother live in the opening of the tale); Esgair Llaethdy, near Myddfai (the farm that the husband and wife move into when they marry); and Llidiad y Meddygon (‘The Physicians’ Gate’) and Pant y Meddygon (‘The Dingle of the Physicians’) (the places where the woman would meet with her sons after she had returned to the lake).

Figure 1. Llyn y Fan Fach, from Picws Du looking towards Waun Lefrith (22 July 2020) [© Nicholas Jones].

The following summary of the legend, by Sioned Davies, is based on a version collected by William Rees in 1841:

[The folktale] tells of a young lad living in the Myddfai area of Carmarthenshire who every day tends his sheep near Llyn y Fan Fach. One day, he sees a beautiful maiden rising from the lake and immediately offers her some bread. She rejects it saying, ‘Cras dy fara! / Nid hawdd fy nala’ (‘Hard-baked is thy bread! / ’Tis not easy to catch me’). He returns home that evening and his widowed mother bakes him more bread; however, the following day the maiden again rejects it saying, ‘Llaith dy fara! / Ti ni fynna’ (‘Unbaked is thy bread / I will not have thee’). On the third day the lad offers her bread that is slightly baked and to his joy, the maiden accepts it and consents to the marriage on condition that the lad is able to recognise which maiden he loves. He chooses correctly and the father gives his daughter a dowry, namely as many sheep, cattle, goats, pigs and horses that she can count in one breath. She proceeds to count, in fives; as she does so, the animals appear out of the lake. A further condition of the marriage is that she must not be struck more than three times without a cause.

The couple are married and settle at Esgair Llaethdy farm where three sons are born to them. Then, one day, the husband rebukes his wife for being slow in fetching horses for them to attend a christening and taps her shoulder with one of his gloves – the first blow. On another occasion they are at a wedding where everyone is happy and joyful; she, however, begins to sob whereupon the husband taps her shoulder – the second blow. Finally, when she laughs at a funeral, he taps her shoulder again – the third and final blow. The wife returns to the lake, accompanied by her sheep and cattle; even oxen ploughing a nearby field follow her, dragging the plough into the lake – it is said that the mark of the furrow can still be seen to this day. But every now and then she returns to this world to meet her sons and teach them about the medicinal properties of plants and herbs that grow locally, and they become famous physicians, the Physicians of Myddfai, attested in Welsh literary tradition from the fourteenth century onwards.Footnote 15

According to Sioned Davies, the legend is a ‘good story, full of tension and drama. Moreover, its basic structure and style is representative of the best of storytellers with its threefold repetition, its clever use of formulae and its passages of dialogue.’ Its aetiological elements, such as the mark of the furrow or the place-names, also aid the recall of events. ‘These names connect the story with the local landscape; they are constant reminders of the significance of the Myddfai area and the legend associated with it’; and the mark of the furrow, which the story says is still visible, relates ‘the past to the present time’.Footnote 16

William Rees's 1841 version of the legend, written in English, was published in 1861 as the preface to The Physicians of Myddfai.Footnote 17 This publication also includes a series of medical remedies based on several medieval manuscripts that date back to the fourteenth century.Footnote 18 These remedies purport to be have originated from Rhiwallon Feddyg (Rhiwallon the Physician) – who, according to the Llyn y Fan Fach legend, was the couple's eldest son – and his three sons, Cadwgan, Gruffudd and Einion, who were Physicians to Rhys Gryg, Lord of Dinefwr in the thirteenth century. Gryg granted them ‘rank, lands, and privileges at Myddfai, for their maintenance in the practice of their art and science, and the healing and benefit of those who should seek their help’.Footnote 19 Thus the succession of Myddfai physicians – the Meddygon Myddfai – renowned for their knowledge of medical practice and learning, can be traced directly from Rhiwallon through to John Jones (the last member of the family of physicians in the direct male line, according to folklore), who died in 1739.Footnote 20 Pountney argues that the likelihood is that the early herbal healers used the folktale to legitimise their practice,Footnote 21 but Wood points out that the fusion of folklore and historical fact is particularly noteworthy as it was the ‘first time this story of an otherworld bride was attached to the quite genuine, but presumably independent, traditions and medieval medical texts associated with this family of famous physicians’.Footnote 22

Into the Orwellian ‘envelope’

Writing in the late 1880s, E. Sidney Hartland presciently observed that the Llyn y Fan Fach legend ‘is still living as a folk-tale, and is apparently even yet possessed of sufficient vitality for growth’.Footnote 23 From a purely artistic point of view, the tale has proved to be highly adaptable with numerous creative reinterpretations of the story appearing throughout the twentieth century to the present day. These include the 1948 novel Iron and Gold by Welsh writer Hilda Vaughan – in which the author ‘introduces a twentieth-century feminist spin in its critique of the social construction of gender roles and the nature of marriage’Footnote 24 – and the 2010 ballet The Lady of the Lake, composed by Thomas Hewitt Jones and produced by Independent Ballet Wales (now Ballet Cymru).Footnote 25 David Pountney's own reimagining of the folktale in his libretto for The Doctor of Myddfai presents a bleak, futuristic dystopian landscape, beset by a mysterious plague and led by an unsympathetic and deficient government. The folktale's combination of legend and historical reality suggested to him ‘a way of using the tale as the basis for a modern libretto’ and he invented ‘a somewhat Orwellian “envelope” into which to set the tale’,Footnote 26 thus enabling him to project a story with universal themes that resonate beyond the confines of its Welsh origins. Pountney's libretto draws on characteristics that are integral to dystopian fiction, including suffering and injustice, loss of individualism, government control and environmental crisis; it also displays what M. Keith Booker describes as ‘oppositional and critical energy or spirit’, which is typically employed at the service of social or political critique.Footnote 27

In the published libretto for the opera, Pountney provides the following synopsis:

[Act I scene 1] The Doctor is retelling the legend to his child. She knows the story well, but the Doctor is distracted, constantly thinking of his patients. A strange new disease has broken out. Whenever anyone receives a blow in the rain, it develops into an horrific and incurable bruise, spreading inexorably over the whole body. The sick are driven to gather beside a lake, where they sing in desperation. The Doctor can get no information from official sources about this disease; he resolves to go and confront the government.

[Act I scene 2] Faced with an unhelpful and hostile bureaucracy, the Doctor discovers that he has inherited certain magical powers. [Scene 3] He gains access to the Ruler himself. The Ruler listens to the Doctor's story, but finally dismisses him. [Scene 4] He cannot allow such private and remote stories to affect his grand strategy. But the Doctor's story has disturbed him. He seeks consolation with a woman ‘from the usual agency’. [Scene 5] But the woman turns out to be the Doctor, who now confronts the Ruler on a truly personal level. At the climax of their scene, the Doctor strikes him. It is raining. The Ruler is now infected.

[Act II scene 1] The State Council meets to debate the crisis caused by the Ruler's mysterious absence. The meeting, tense and acrimonious, is twice disturbed by inexplicable interruptions. At the third, the Doctor appears, and begins to explain his origins, but he is interrupted by the Ruler, who demands to be taken to the lake to be cured.

[Act II scene 2] At the lake, the Doctor refuses to cure the Ruler, saying that he is concerned with nations now, not with individuals. The sick, hearing of the Doctor's presence, trample him to death in their desperation for a cure. [Scene 3] The Child arrives, and orders the Ruler to walk into the lake. As the new Doctor of Myddfai, she takes control.Footnote 28

As one can gather from this synopsis, Pountney's libretto is not a simple, straightforward retelling of the legend, yet the futuristic world shares a deep connection to its mythical past. As Simon Rees has perceptively observed: ‘The folktale begins as a myth and ends as a justification for the medical expertise of a group of historical doctors, whereas [the] libretto starts with a realistic, vivid description of a future society, but as the story progresses the mythical and allegorical elements come back out of the text, and we see that we're looking at an archetype again.’Footnote 29 Indeed, the two stories – the folktale itself and Pountney's dystopian scenario – share a complex and beguiling relationship: they are juxtaposed and superimposed, interleaved and enmeshed, a strategy that creates not only tension and opposition but also a particular ‘aura’ or atmosphere that can sometimes be disorientating or simply strange.

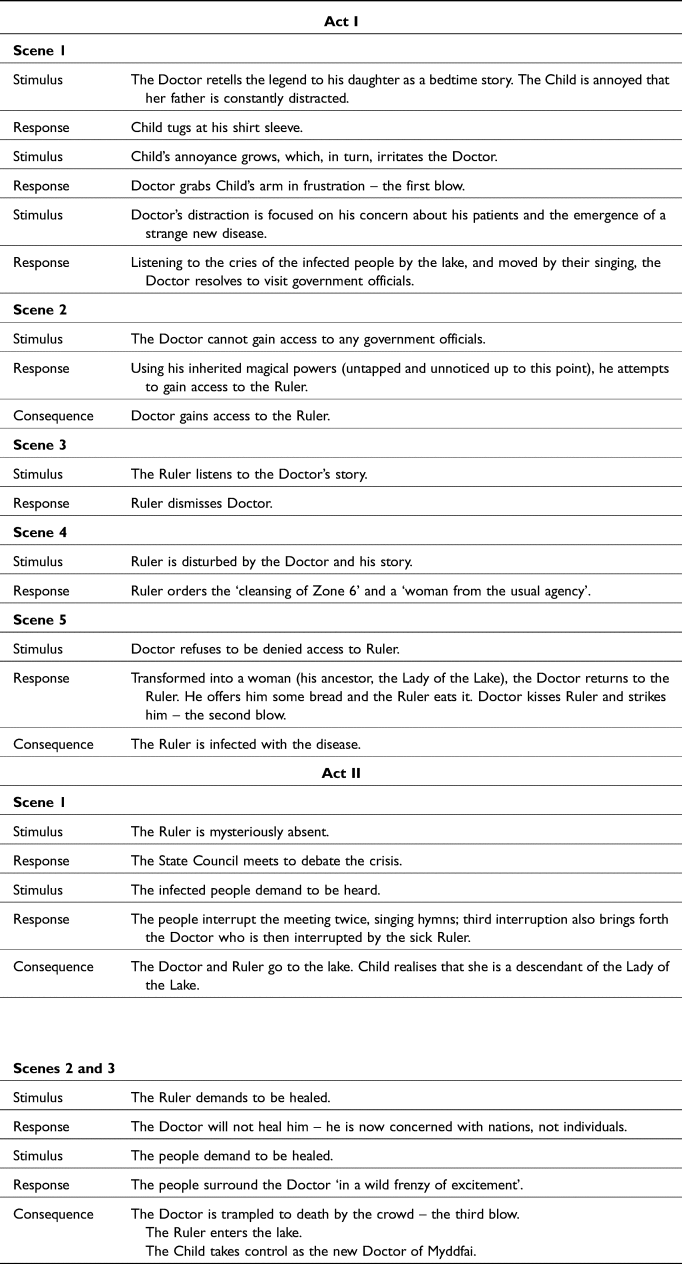

Sioned Davies has valuably analysed the structure of the folktale's narrative in relation to a series of episodes consisting of three main categories: stimulus (marking a change in the story environment which prompts a character to respond in some way); response (a description of the character's behaviour in response to the event); and consequence (marking the attainment or non-attainment of the character's goal).Footnote 30 Sioned Davies's analysis is summarised in Table 1. Davies outlines an overarching two-episode sequential story, where the ‘condition’ is laid down by the fairy bride in the first episode and broken in the second. Both episodes have a tripartite structure, or three sub-episodes: three attempts by the man to win the woman's hand, and three causeless blows. As the libretto for the opera is characterised by the blurring of the boundaries of legend and reality, such clear-cut episodes of stimulus–response–consequence are more problematic to identify. Nevertheless, Table 2 is an attempt to propose such a sequence.

Table 1. The Llyn y Fan Fach legend, overall stimulus–response–consequence structure (after Sioned Davies).

Table 2 shows that Pountney has retained the ‘three-blows’ motif of the original tale, and extends the archetypal formula, or folkloristic trope, of the storyteller's threefold repetition technique into other areas of the libretto, including the dramatic triple interruption of the choral hymn singing in Act I scene 1 and Act II scene 1, and the unfolding of the folktale in three separate parts, first by the Doctor (Act I scene 1), then the Child (Act I scene 4), and finally by both the Doctor and the Child (Act II scene 1). He also makes emblematic use of the number three: in Act I scene 2, there are three Officials; in Act I scene 4, the Ruler makes reference to three Gainsborough paintings in his dressing room; in Act II scene 1, there are three Guards; in Act II scene 3, three girls appear in the lake; and in the closing moments of the opera, the Child exits the stage accompanied by the three Officials.Footnote 31 Pountney's modern story also consistently makes connections and allusions to various aspects of the folktale. These are sometimes articulated in an obvious way, such as the blows in the original corresponding to the touches, slaps or strikes in the modern story which, when received in the rain, result in incurable bruises and disease; or when, at the end of the opera, the names of the physicians’ medicinal plants and herbs are intoned first by the Doctor, then the three girls in the lake, and then finally the Child. But they are also made in more subtle ways, such as Act II scene 2, where reference is made to the mark of the plough (‘And here, where the red claw / Of my ancestors ploughs its furrow / Down the fan’);Footnote 32 or Act I scene 5 where the Doctor, surreally dressed as a woman, invokes the magic and mesmeric qualities of his Lady of the Lake ancestress, with a fish in her (his) hair and an offering of bread for the Ruler – a gesture that confuses the Ruler and prompts him to respond aggressively: ‘I am not a beggar.’Footnote 33 Pountney also reminds us that the folktale begins with the aftermath of a war, and the impact of a distant conflict is an important background element of the modern story.Footnote 34

Table 2. The Doctor of Myddfai, libretto, overall stimulus–response–consequence structure.

But the modern story also reflects some of the real-life issues that evidently preoccupied the librettist in the early 1990s. In his pre-premiere interview with Rees, Pountney states that the futuristic scenario has ‘a degree of resonance with contemporary ideas’, particularly in relation to the references to ‘a kind of arrogant continental government’.Footnote 35 He reveals that the libretto was written at a time when he was ‘profoundly sceptical about the whole idea of a bureaucratic superstate based in Brussels’, and this resulted in ‘a good deal of personal feeling about bureaucracy in the piece’.Footnote 36 The libretto therefore was written against the political backdrop, which remains relevant today, of the UK's strained relationship with Europe; but it was also written at a time when Welsh devolution was firmly on the agenda, a political aim that was eventually realised just fourteen months after the first performance of the opera in the referendum of September 1997.Footnote 37 Furthermore, Pountney draws attention to the mysterious malady that affects everyone in the work. He contends that although it is difficult to argue that the blows struck by the husband in the folktale are blameworthy (the three ‘strikes’ are gentle admonishments, not full-on punches), the disease in his libretto is a symptom of governmental mismanagement – however, he has left open to interpretation whether the cause is chemical (an attempt by the government to subjugate the population by foul means) or merely symbolic.Footnote 38

Nonetheless, the pollution of the atmosphere ‘has caused normal human contact to become something terrifying’.Footnote 39 At the start of the opera, while attempting to retell the folktale to his daughter, the Doctor is distracted by the voices of his patients that he can hear in his head. Towards the end of the scene, the Doctor, alone and distressed, exclaims:

Each day they come,

More and more pitiful stories,

Abject little dramas,

But now a creeping tide of death,

Whose cause I search and search.

I write, I ring,

But everywhere is silence –

Only the sound of suffering.

…

The officials have locked their doors.

We are cut off behind a curtain of rain.

And the dying can only gather beside the lake and sing.Footnote 40

When, at the start of the next scene (Act I scene 2), the Doctor arrives at the government offices, the First Official reprimands him for attempting to sit down: ‘Don't touch the chair. / The shaking of hands is considered unhygienic. / You should know that.’Footnote 41 While Pountney does not specify to which contemporary disease he is making reference, several reviewers at the time of the first performances suggested the HIV/AIDS pandemic.Footnote 42 Moreover, with its particular resonance within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, the scenario takes on a new, fresh perspective, bringing a hauntingly poignant present-day relevance to this part of the libretto. And yet, Pountney also emphasised that all of the topical resonances and political themes incorporated into the modern story ‘are treated in a strictly archetypal way, as elements in a modern mythology’.Footnote 43 For him, The Doctor of Myddfai ‘is not a didactic piece at all, but I would say deliberately elliptical’,Footnote 44 and that ‘any message it conveys should be first and foremost musical’.Footnote 45

Composer–librettist collaboration

The Doctor of Myddfai was commissioned by Welsh National Opera, with funds provided by the Arts Council of Wales, Arts Council England and S4C. It was first performed on 5 July 1996 at a ‘preview’ event at the New Theatre, Cardiff. The official premiere took place the following week, on 10 July, at the North Wales Theatre, Llandudno, with a repeat performance there three days later, followed by further performances later that year across the UK.Footnote 46

In her memoir, Judy Arnold (Davies's manager from 1975 to 2006) recounts that she first received a phone call about the project in May 1992 from Matthew Epstein, who at that time was General Director of Welsh National Opera.Footnote 47 With the calamitous 1987 Darmstadt production of his previous opera, Resurrection, still fresh in his mind, Davies was at first reluctant about writing another opera. According to Arnold: ‘Resurrection had proved to be a disaster. The director had taken no notice whatsoever of Max's own libretto and stage instructions, and what had emerged was an entirely different animal. Max was totally shattered by the experience.’Footnote 48 However, Davies gradually warmed to the idea of composing a new opera after he had received assurances from Epstein that a suitable director would be involved with the project from the outset. Epstein came back with a name – David Pountney – a suggestion to which Davies responded positively. Pountney had established a distinguished reputation as an opera director, mainly through his role as Director of Productions at Scottish Opera (1975–80) and English National Opera (1982–93); he also had a strong connection with Welsh National Opera, having first directed the company in 1975.Footnote 49 Pountney's role as librettist, however, was not communicated to either Davies or Pountney at this early stage; this came later, when Epstein met with them both to discuss the project at Arnold's London flat. ‘I had no idea what I was in for,’ admitted Pountney, ‘but as the conversation progressed it became clear that Max was to write an opera for WNO's 50th anniversary season, and … it also became clear that I was to attempt to supply a libretto’:

This was by no means obvious, because Max had always written his own words, very successfully in the case of the smaller-scale theatre works. I suppose the unspoken subtext was that I was being put on board to pilot a project that would be full-scale, but feasible within the constrained financial and practical limits of WNO in 1996. The brief was that the work should contain an element of Welshness, show off the company, and celebrate its chorus. Max and I regarded each other cautiously, and decided to go away and see what we came up with.Footnote 50

The relationship between composer and librettist progressed cordially. Both individuals spent the next few weeks trawling through Welsh literature, including the Mabinogion.Footnote 51 Even at this early stage, they had agreed to ‘write something modern, or at least with an immediate contemporary resonance’.Footnote 52 By the time they met in London in November 1992, they had alighted on the subject. In his private journal for that month, Davies writes: ‘Good meeting at the Colosseum with David Pountney – he has turned up an adaptation of a Welsh folk-tale which looks very promising. Lots of chorus work, a sexual transformation and present-day mythic elements. Suggested that the chorus should sing its hymns in Welsh.’Footnote 53

In fact, the folktale in question – a story that does not appear in the Mabinogion – was suggested to Pountney by a friend of his wife, Mary Uzzell Edwards, a teacher based in the Swansea Valley, who had dramatised the tale with several of her primary school classes.Footnote 54 Pountney found the story ‘immediately attractive’: ‘apart from the conventional “lady in the lake” beginning’ it possessed ‘the unusual feature for a folk-tale of emerging quite specifically into three dimensional historical reality’.Footnote 55 According to Arnold, ‘the idea was that David and Max would collaborate all along with the writing of the libretto. But this did not happen. David wrote the libretto in its entirety, sending drafts to Max as he went along for approval, all of which were accepted without demur.’Footnote 56 Given the fact that The Doctor of Myddfai was the first dramatic work for which Davies did not write his own libretto, the situation could have given rise to artistic conflicts of interest, disagreement and mistrust.Footnote 57 But in the end it turned out to be a wholly constructive process.

The final draft of the libretto was completed relatively early on in the whole process, on 2 November 1993.Footnote 58 The commission for the opera was also confirmed in that year, and the date for the premiere was set for June 1996.Footnote 59 In the interim, Davies was engaged in a period of exhaustive professional activity. This involved the fulfilment of various commitments with the BBC Philharmonic Orchestra and the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra (for both of which he was appointed Associate Conductor and Composer in 1992), in addition to the composition of the Eighth and Ninth Strathclyde Concertos (1993 and 1994), the Fifth Symphony (1994), The Beltane Fire (a 40-minute orchestral work, 1995), and nearly twenty other works besides – including The Three Kings (1995), a 50-minute cantata and the final work completed before work on the new opera commenced. The intensive nature associated with such a heavy workload clearly had an impact on the composition of The Doctor of Myddfai. In her memoir, Arnold relates that she had to attend a meeting with Anthony Freud (who had replaced Epstein at WNO in 1994) to inform him that Davies was behind in his schedule for completing the opera – a situation that was ‘very unusual’.Footnote 60 As it transpired, the date of the first performance of the work was pushed back by only one month.

According to his private journal, Davies started work on the opera in August 1995. Composition progressed slowly at first, but the pace increased during September; by mid-October, he was ‘working quickly’. On 17 October, he reported that ‘Myddfai is going well. … Had lunch with David Pountney – v. constructive.’ But on 4 November, he was somewhat less optimistic: ‘In Myddfai, I'm doing my best, what I can & all that. It is such an unholy rush – if I don't produce c.10 pages of full score out of the corresponding number of pages of sketch each day I feel guilty and depressed, and even this is too little, with an end of November deadline.’ He persevered but missed the deadline, eventually completing the work, at home in his croft house, Bunertoon, Island of Hoy, on 12 December 1995.Footnote 61

Into the ‘labyrinth’

Pountney's libretto provided Davies with a potent creative stimulus that reflected closely, to a remarkable degree, some of the composer's lifelong preoccupations as expressed in his previous operas, chamber operas and music-theatre works: namely, an aversion to bureaucratic officialdom, the corrupting capacity of political authority, the questioning of religious faith, the repression of individual identity, the exploitation of the environment, the predicament of an individual (or individuals) in extremis, and the topics of betrayal, madness and good versus evil. In a review of the first performance of the work, Stephen Walsh perceptively observed that ‘It might seem that … David Pountney was consciously synthesising a catch-all Max libretto.’Footnote 62 In similar vein, Roderic Dunnett also noted the many Daviesian resonances in Pountney's libretto, not least in the ‘Tanist’ relationship between Doctor and Ruler: ‘light, dark (or alternating) twin sides of the same coin’.Footnote 63 However, Dunnett also complained about what he regarded as the rather abstruse nature of the plot: ‘The pestilence which threatens Pountney's technologized bureaucracy, with its tortured ruler, smug aficionados and cowed acolytes, is – like much of the plot – deliberately nebulous.’Footnote 64 Dunnett's criticism of the plot is indicative of other reviews at the time. Andrew Clements, for instance, stated that whilst the libretto is located in the present day in an anonymous, bureaucratic state, ‘What the opera is really about is harder to divine.’ He also called attention to an aspect of the libretto with which other commentators found issue: ‘[Pountney's] text is prolix – there are just too many words to put over, with not enough space for the music to expand around them.’Footnote 65 Despite such reservations, though, Davies's music was generally well received by the critics. In relation to the score, for instance, David Murray found it ‘pithy and striking’; Paul Driver, ‘a model of theatrical efficacy’; and Geoffrey Alvarez, ‘sensitiv[e] to vocal tessitura and orchestral balance’.Footnote 66 Walsh effused that ‘The Doctor of Myddfai ranks with Davies's best theatre pieces, and it's certainly one of his most intriguing recent scores.’Footnote 67 From Davies's point of view, the first performance represented something of a personal triumph. In his private journal for July 1996, the composer records the following:

The new opera in Cardiff very positive. Had to make quite small adjustments but in most places the score works. Paul Whelan as the Dr. of Myddfai, Gwynne Howell as the Ruler and Lisa Tyrell as the Child beyond reproach, and the work of Richard Armstrong and all the music staff helpful as I never experienced before in the opera house, and self-effacing with it. Excellent staging – David Pountney's direction of his own opera & the sets, costumes and lighting all marvellous. For me the real heroes the chorus. Absolutely magnificent. And the orchestra were giving, forgiving & patient: this mostly R.A.'s [Richard Armstrong's] doing.Footnote 68

As mentioned above, Davies started composing music for the opera in August 1995. However, he had started to think about the project before this time. As the libretto, unusually, was not of his own creation, he understandably began by devoting a considerable amount of time studying the text, carrying the libretto around with him ‘on trains and planes’ and working on various aspects of the work's musical dramaturgy, including the crucial relationship between words and music and the overall arc of the drama.Footnote 69 He then proceeded to ‘define tonal areas which would not be related by direct tonality but by modal means’. When the writing stage began, he would take walks on Hoy, ‘plotting out in sound and establishing certain musical areas which are going to operate at certain times in the opera’ and ‘walking the connection between them’:

And that's the basic method – to have these big areas and then start filling in the threads which link them and going through the ‘labyrinth’ with all of the text. I have given different characters specific motifs which move and change as they change in the opera. The Doctor particularly, his development is musically quite interesting but there are things which remain the same. And I hope it sounds dramatic but it's a long slow process over the whole thing.Footnote 70

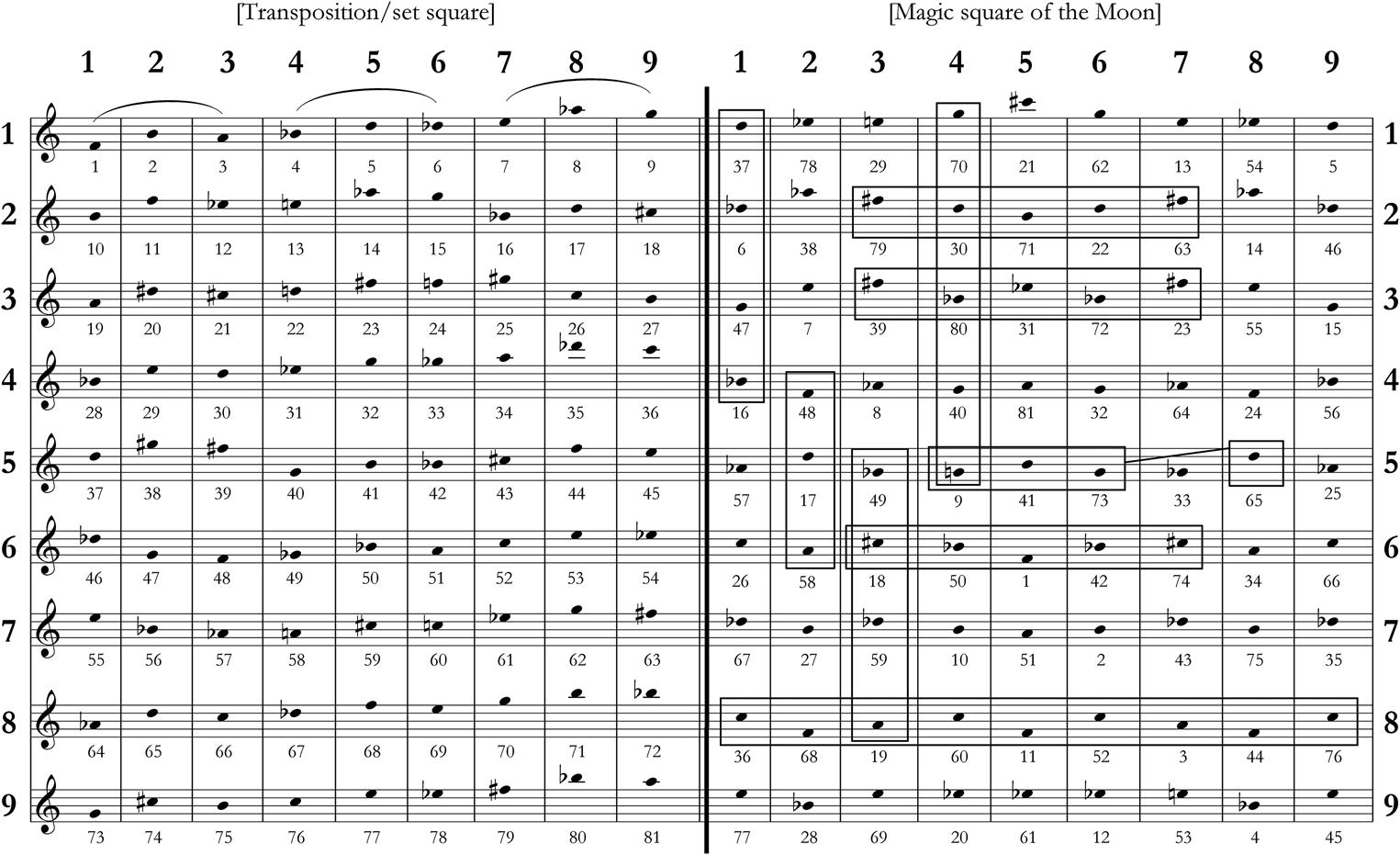

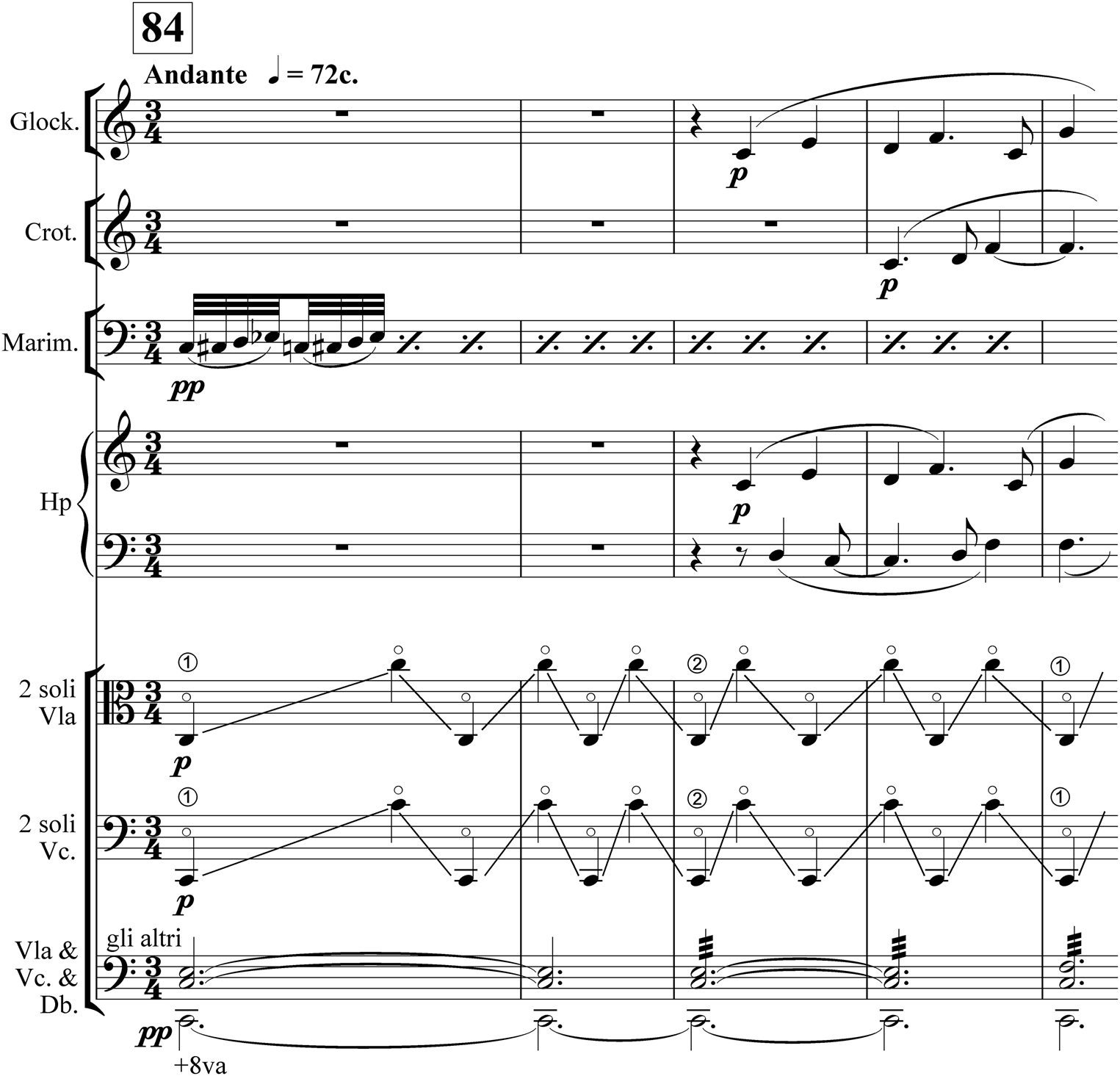

Central to this ‘long slow process’ is a tried-and-tested and highly idiosyncratic compositional technique which is underpinned by pre-compositional workings, including sets and pitch charts, and thematic material derived from transformation and magic square processes.Footnote 71 A page from these workings is given in Example 1. This example presents a pair of 9 × 9 squares, which together constitute the principal source material for the work: the original transposition square (or ‘set’ square, to use Davies's own labelling) is on the left, and the resulting magic square of the Moon – or ‘Luna’ – on the right (durational values for all pitch classes have been omitted). In the draft score for the opera, Davies appears to refer to these two squares combined as constituting the ‘doctor luna square complete’.Footnote 72 Example 1 also includes Davies's own boxed annotations to highlight certain tonal triads, such as F major and B minor, but also D minor, G major/minor, B♭ minor, E♭ minor and F♯ minor (the only anomaly to this tonal-triad rubric is the collection of notes in the top left-hand corner: G–B♭–D–D♭). The majority of these ‘tonal areas’, or pitch centres, are used in the opera.Footnote 73 The most prominent of these are B and F (the first two elements of the 9-note set in the left-hand square of Example 1): these function for the entire work as the ‘modal tonic’ and ‘modal dominant’ respectively. As Example 2 demonstrates, the pitch centre B is specifically associated with the Doctor himself; but he is also associated – especially in his vocal lines – with the pitch-classes D, F and G♯/A♭: I term this sequence of ic3 intervals the ‘Doctor axis’.Footnote 74 Other pitch centres are associated with different characters or concepts/topics: the Ruler with B♭ and the Child with D♭; the Child also shares the pitch centre B with the Doctor (and his axis); she also shares the same pitch centres as the People (B and C♯). In the first act, the modal dominant F is clearly associated with the rain, a natural element that causes the bruise (E♭), but in Act II scene 3, F is associated with the Myddfai herbal plants, natural resources that have healing properties;Footnote 75 in a similar vein, the pitch centre C (with minor third E♭, perhaps making a connection to the bruise) is related to betrayal in Act I, but changes in Act II scene 3 to signify innocence and hope (with major third E♮).

Example 1. Transcription of main transposition/set square and magic square for The Doctor of Myddfai, British Library MS Mus 1465, fol. 84.

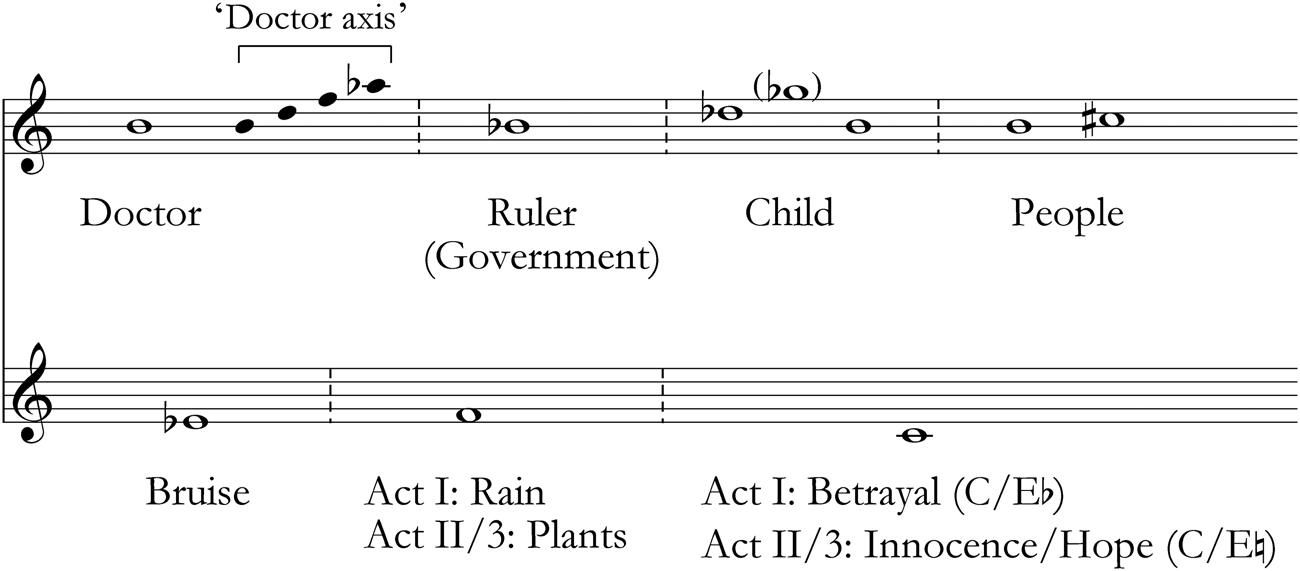

Example 2. Main pitch centres.

Example 3 fleshes this out in more detail: here, global pitch centres are mapped on to the overall structure of the opera, outlining an overarching harmonic framework operational throughout the opera. Example 3 also highlights the use of the ‘Death’ chord (D/F♯–E/G♯) at several points in the opera – labelled as such because in the opera Taverner it is associated with the figure of Death, both real and symbolic, and used, as a kind of ‘leitmotif’, in numerous works at the time and thereafter.Footnote 76 Its first appearance in The Doctor of Myddfai, in the first scene of Act I (on brass, with A/E♭ dyad), connects the folktale's ‘three causeless blows’ taboo to the futuristic story's incurable bruises, which ultimately lead to death. The second appearance, at the end of Act I (first on strings and then horns), underscores the libretto's second blow – the infection of the Ruler as a result of the Doctor's strike. The third appearance, at the end of Act II scene I (on strings), signals the murder of Minister No. 10; and the final appearance, towards the end of Act II scene 2 (again on strings), throws an ironically pessimistic light on the proceedings – ironic because it comes at the point where the Doctor is referring to the healing properties of the physicians’ plants and herbs – and is used to foreshadow the Doctor's death at the end of this scene.

Example 3. Main pitch centres in operation across the opera.

The elements of tension and opposition, both of which are deeply implanted into the libretto, are also very much in evidence in the music on three main levels. The first relates to the pitch centres outlined immediately above – the duality between F and B, B and B♭, B and D♭, and so on (this will be discussed further at various points below). The second level concerns musical style. In the opera, Davies employs three distinct stylistic languages: his own; a quasi-folk, modal idiom (also discussed below); and a satirical, parodic style which is used to depict the government. This latter style, for instance, is heard at the opening of Act II and sets the tone for the acrimonious meeting of the officials. Marked ‘alla marcia’, the music is sardonic and detached and initially spotlights a spiky piccolo theme (an ironic reworking of the alto flute line from Act I scene 1 at Fig. 1), jangling tambourine and lumbering timpani line; later (at Fig. 6) the music is characterised by jerky dotted rhythms on con sordini ‘wa wa’ brass, side drum and small suspended cymbal. However, the way in which Davies moves between these three different styles is seamless; his general approach is one of integration rather than disintegration. Nevertheless, although formal fragmentation and a fiery, hard-edged expressionist language are avoided (qualities that typify the theatre pieces of the mid-to-late 1960s), a sense of anxiety is ever-present, simmering ominously just below the surface.

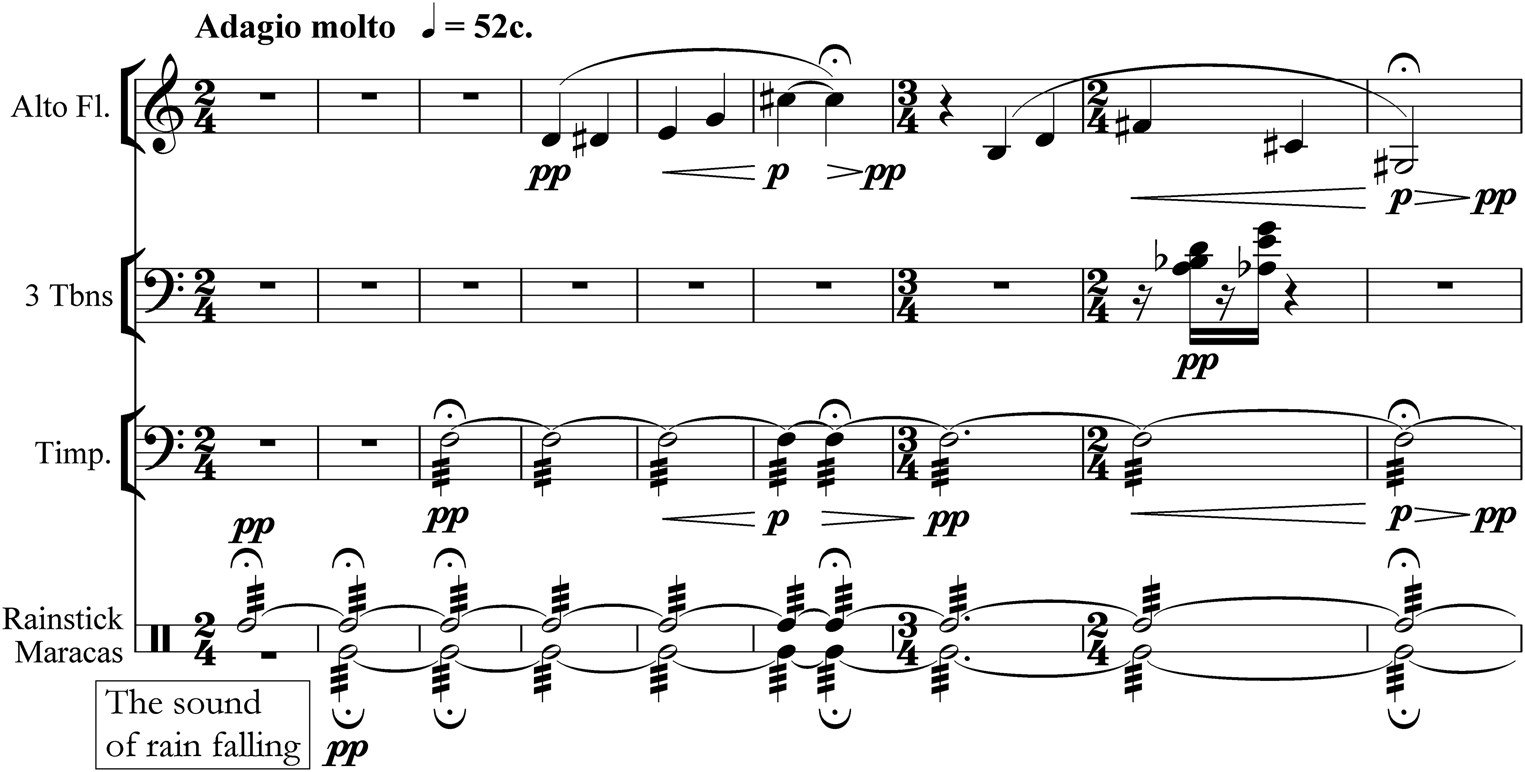

The third level is in relation to the main characters. The Doctor and Child are associated with particular instruments: the Doctor with the alto flute, and the Child with the harp. The Doctor's character is established right at the outset of the opera: set against the melancholic sound of falling rain, evoked by rainsticks and maracas, and supported by a modal dominant F tremolando in the timpani, the lugubrious and evocative tones of the alto flute effectively etch out the mysterious character of the Doctor (see Example 4).Footnote 77 Throughout the first scene of Act I, both the Doctor's and the Child's lines are rooted around the pitches associated with the ‘Doctor axis’, especially B and F. But when we next see the Child, at the start of Act I scene 4 (where she is relating the second instalment of the folktale), her line and the music that accompanies her are centred on D♭ mixolydian. The change in musical style at this point is quite striking: the music adopts a rather captivating and lighter folk-like character, and the overall effect is enhanced by the use of the harp – an instrument that is emblematic of Welsh folk music (see Example 5).

Example 4. Opening.

Example 5. Act I scene 4, Figs. 94–95+3.

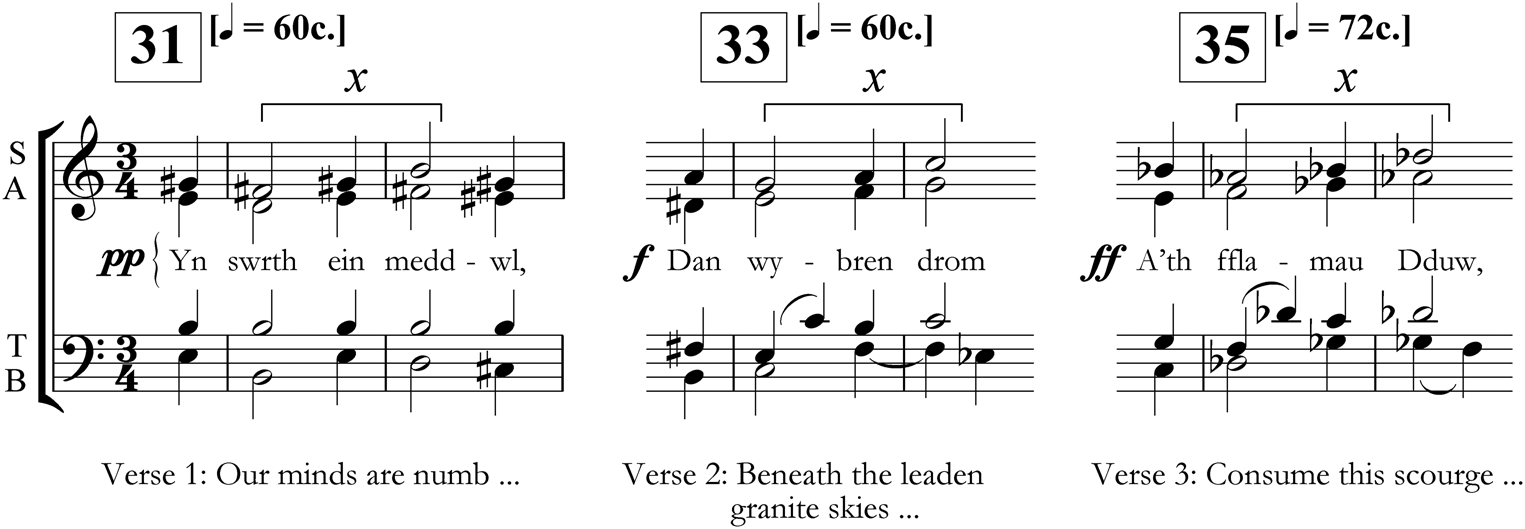

The Child also has her own motif. As can be seen in Example 5, it consists essentially of a rising perfect fourth (ic5), an interval which is filled, in its most basic form, by a root–second–fourth figure (x), or more decoratively by root–third–second–fourth (y) or root–third–second–third–root–fourth figures (z). This rising ic5 motif can be witnessed throughout this scene (where it is sometimes ‘corrupted’ to the tritone, ic6); it is also heard when the Child first returns in the second act (scene 1, Fig. 58), and fortissimo, in a theme on strings covering four octaves, in the transition to the next scene (Fig. 60+5). Furthermore, the basic version of this motif – x – is used in the music for the two Welsh hymns: a summary of its use in the first hymn is presented in Example 6. The fact that Davies associated this motif with both the Child and the People strongly suggests that he intended an intimate connection between the two, an idea that is given additional support by the fact that Davies employs a modal harmonic language for both and also that they share pitch centres; indeed, as a result of this firmly yoked relationship, it could be further argued that it is the Child who finally emerges as the person imbued with deep, genuine compassion for the plight of the citizens of Myddfai, and not the Doctor.

Example 6. Act I scene 1, opening chorus parts at Figs. 31, 33, 35.

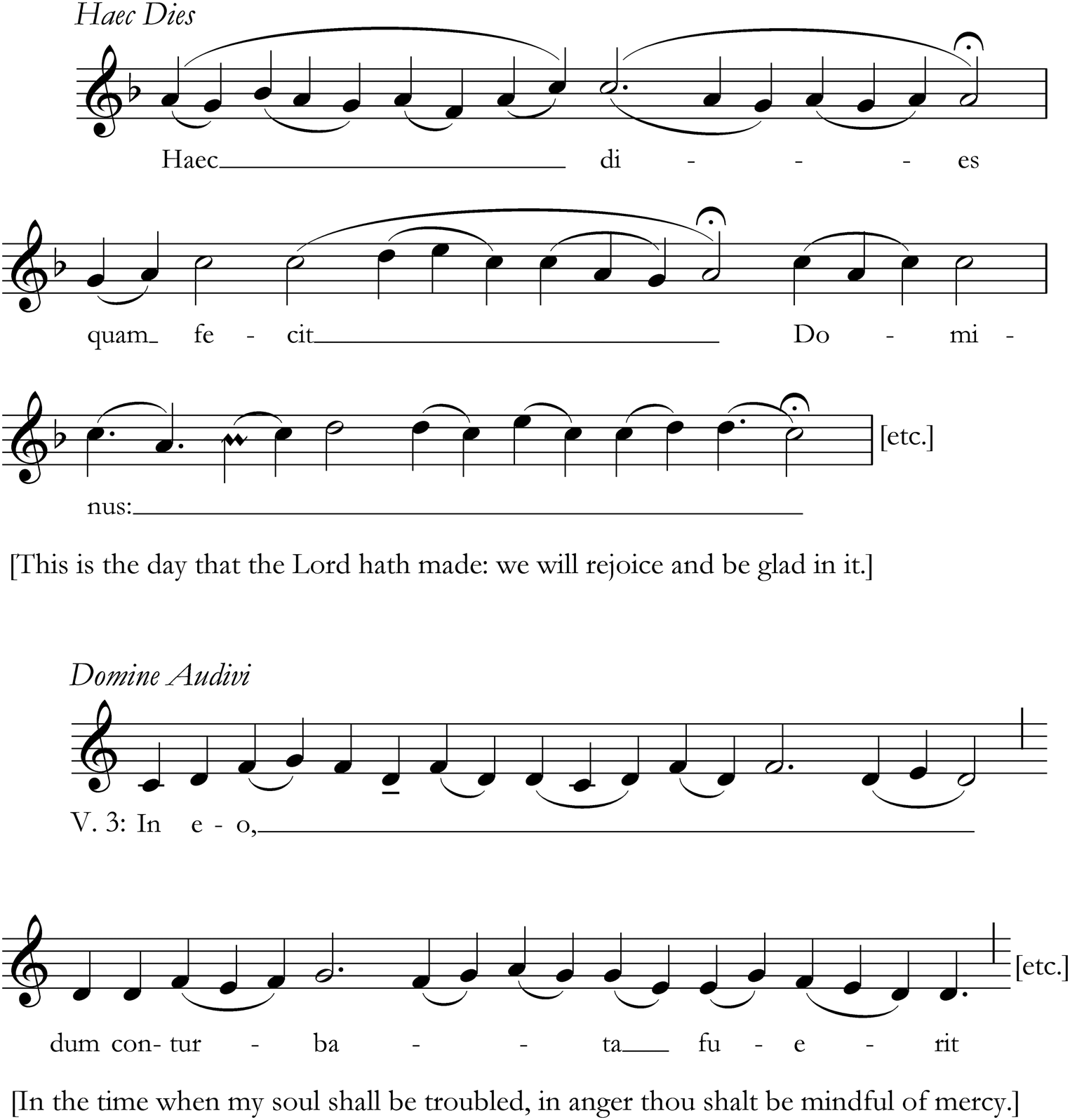

The pre-compositional materials for the opera indicate that the main sets originate from two plainsong sources: Haec Dies and Domine Audivi (see Example 7).Footnote 78 Whereas the Doctor's material throughout the opera seems to be taken from sets originating from the Haec Dies plainsong, the Child's and the People's ic5 motif appears to be originate from the Domine Audivi plainsong: motif x can be seen clearly at the start of the third verse, the portion of the plainsong that Davies decided to extract. Translations of both texts have also been provided in Example 7. Given Pountney's dystopian scenario, Haec Dies seems to be exquisitely ironic, but for Domine Audivi, the notion of showing mercy seems highly appropriate for the predicament of the People's suffering. This might also explain the brief but achingly beautiful episode in Act I scene 4, which also uses motif x (see Example 8). This constitutes the only moment in the opera that is purely diatonic, a B♭ major to G minor progression in the strings, which is suddenly and violently crushed by a shattering dissonance – consisting of a combination of B and F minor triads – in the woodwind and brass.

Example 7. Transcription of Haec Dies and Domine Audivi plainsongs, British Library MS Mus. 1420, fols. 2 and 3.

Example 8. Act I scene 4, Figs. 115+7–115+12.

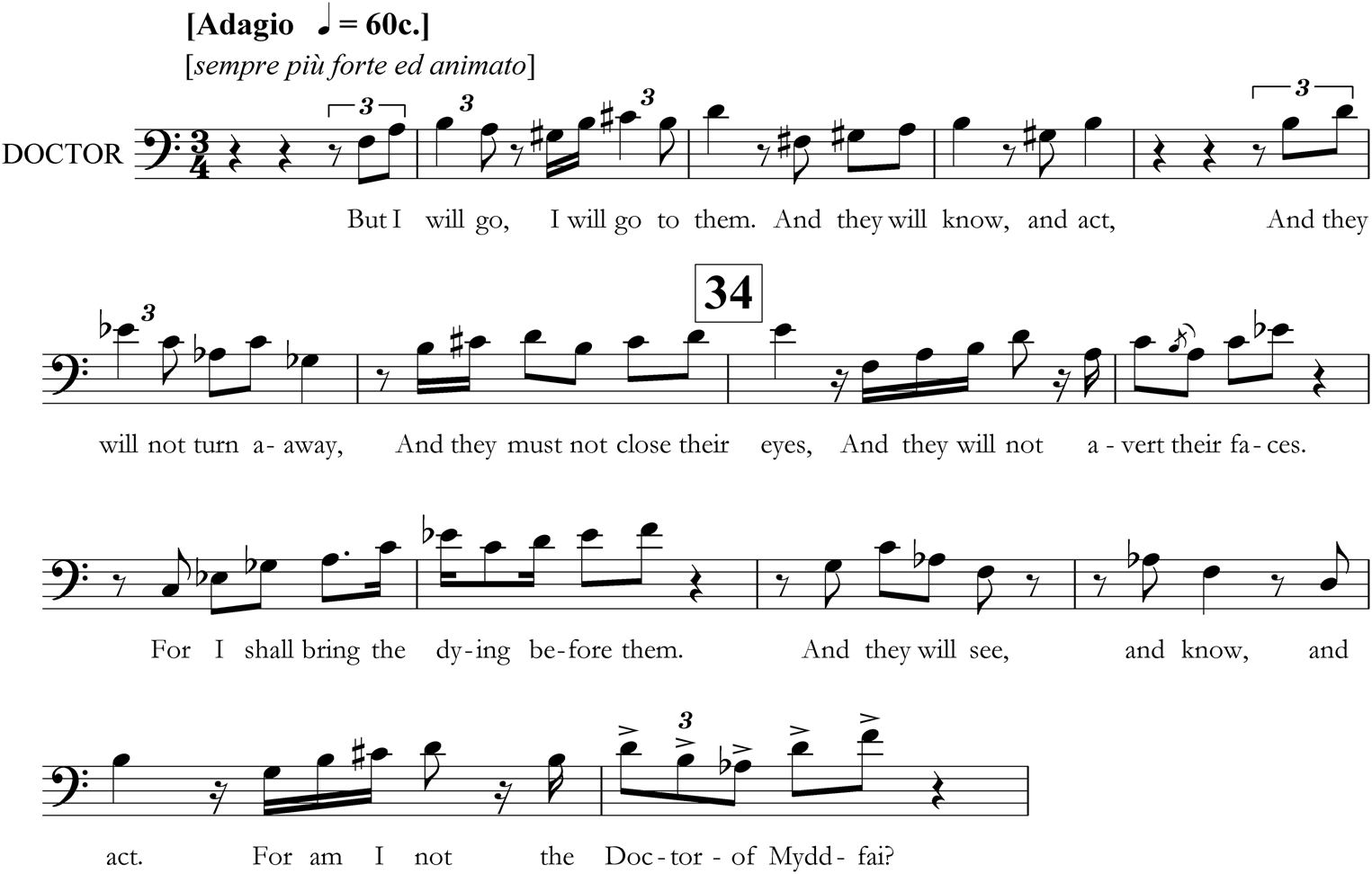

The Doctor also has a characteristic upward melodic ‘motif’, but it is much less fixed and more fluid and gesture-like in character than the Child's – an observation that suggests that whilst his character is continually in transformation, the Child's character remains more constant and stable. As well as establishing his pitch centre (underpinned by tremolando B in the timpani and B-based harmonies in the pizzicato strings), the first three notes that the Doctor sings – B–D–F♯ (at Fig. 2) – highlight the upward profile of the motif. These pitches are clearly derived from the second line of the Luna magic square, Example 1, elements 5–7 (and are also heard in the alto flute line at the start of the opera – see Example 4). The motif's intrinsic triadic property is retained on several occasions in the first scene (such as F–A–C at Fig. 10 and B–D♯–F♯ at Fig. 23), but on the whole, its upward motion is its most prominent feature, especially at the start of new entries. However, this is by no means consistent, and it should be stressed that the pair of squares that, combined, constitute the ‘doctor luna square’ (Example 1 – which is unfolded, very freely with elaboration, from Fig. 29 in the Doctor's part, row by row) and the ‘Doctor axis’ should also be considered as ‘motifs’ for this character. For instance, towards the end of Act I scene 1, a proud and defiant Doctor, propelled into action by the sound of suffering by the lake, resolves to visit the government (see Example 9). The Doctor's line here incorporates the upward motif throughout, draws freely from sub-units 1–2 of the Luna set square, and focuses on the pitches of the axis. And in Act II scene 2, when the people close in on the Doctor – ‘The healer. / Touch him.’Footnote 79 – the chorus's soprano line is based on the Doctor's Luna set square (Fig. 76), and later the lines of the whole chorus – ‘The Doctor? Gone!’Footnote 80 – are aligned to the pitches of his axis (Figs. 81+5–82).

Example 9. Act I scene 1, Figs. 33+2–35-1 (Doctor only).

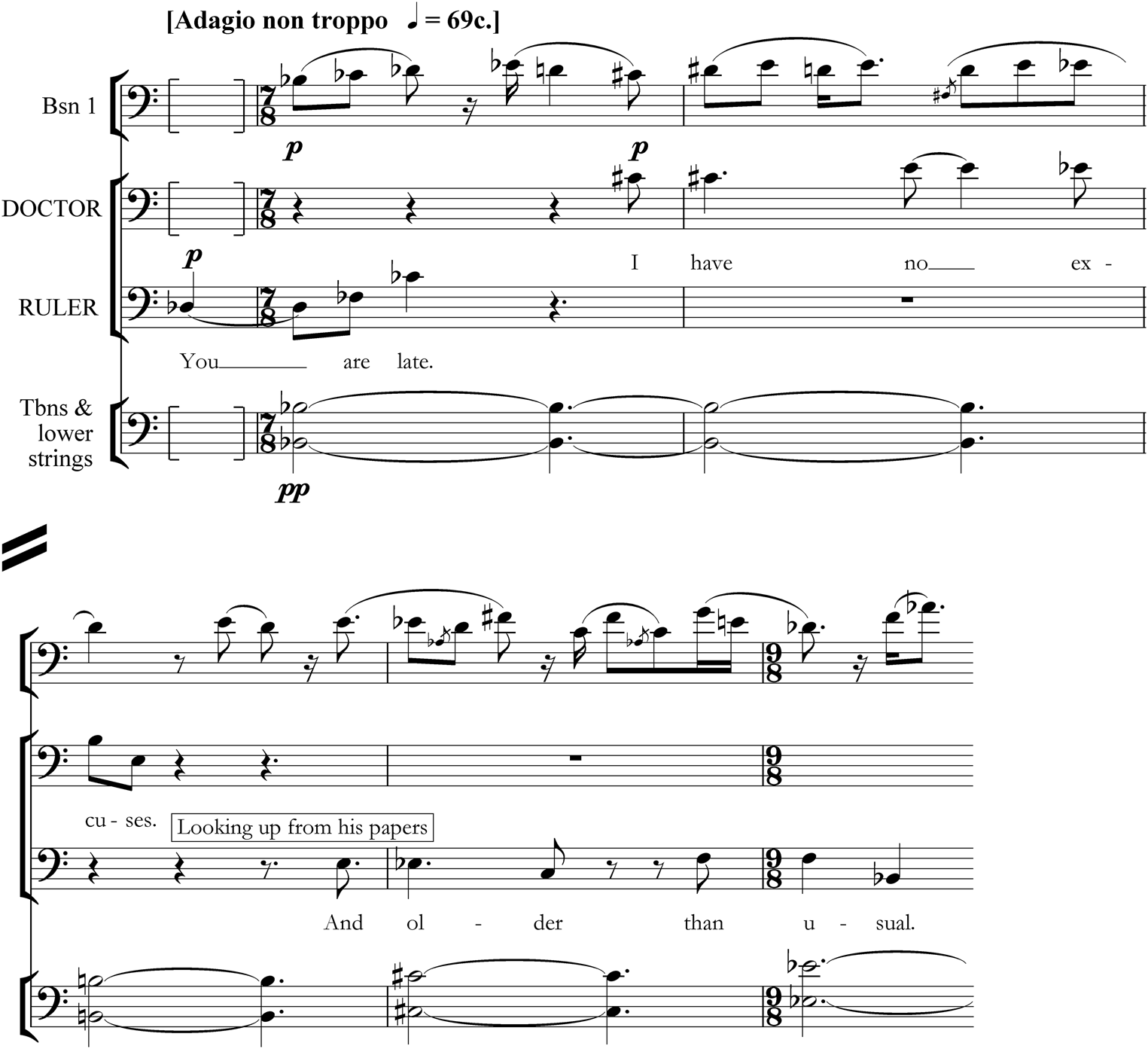

The B♭ pitch centre used for the Ruler is unrelated to the Doctor and was no doubt chosen to symbolise the incompatibility and inherent sense of conflict between the two protagonists. As the opera progresses, however, areas of connection between the two start to emerge. Example 10 shows their first exchange, in Act 1 scene 3 – a very tense encounter, with a dark and threatening undercurrent. It will be seen that the Ruler, too, appears to be associated with his own instrument, the bassoon, which unfolds an intricate, meandering melodic line drawn from an 8-note Mercury square, which again appears to be linked to the Ruler; this square is derived, like the Doctor's, from the Haec Dies plainsong.Footnote 81 It will also be noted that the Ruler's opening phrase is an upwards gesture – a feature that is used throughout this scene (especially at Fig. 81), thus providing the audience with an aural link to the Doctor's upward motif. But whereas the Doctor's vocal line, up to this point, has been mostly conjunct and ‘smooth’ in profile, the Ruler's vocal line is more disjunct, involving a greater number of leaps; moreover, the Ruler's pitches do not correspond with the Doctor's axis. However, as the Doctor starts to confront the Ruler with the stark reality of the public health crisis in ‘Zone 645’ – ‘It is the war – the war and the rain. / No authority dare speak its name. … And yet this poison is a fact. / The deaths it brings are facts.’Footnote 82 – the Ruler's lines become progressively more influenced by the axis. The turning point appears to occur around Fig. 83; certainly by Fig. 86, the Ruler has a long stretch of pitches based on the axis; and by the time we arrive at the end of the scene, the pitch sung by both men is B.

Example 10. Act I scene 3, Figs. 66+8–66+13.

Act I scene 3 comes at the point in the opera where the Doctor has just discovered, in extremis, the magical powers of his water spirit ancestress – a discovery that stirs an atavistic recollection in his own genetic makeup and sets in motion a train of events that lead ultimately to his own death and the rapid, yet perhaps inevitable rise of his daughter to a position of power as the new Doctor. Act I scene 5 plays a crucial part in this process. Here, his compassion as a healer starts to erode, and megalomania and insanity begin to take its place: not only does he strike and infect the Ruler but he also drinks wine from his lips, a kiss that acts as a powerful symbol of betrayal – a betrayal as his role of curer, a betrayal of the people and a betrayal of his role as father. At the same time, the Ruler, clearly disturbed by the Doctor's visit in scene 3, also starts to question and eventually lose control of his position. David Pountney, in his pre-premiere interview with Simon Rees, outlines the dereliction of duty and the failure of these two main characters. In the climactic duet in Act II scene 2, the Doctor has forgotten what his job is – to cure. He has become ‘a generalised curer, an idealist and a political manipulator’ and has now taken the place of the Ruler. The Ruler realises that there is no cure and that his past decisions have led to unforeseen problems elsewhere. As Pountney states: ‘The point about the Doctor and the Ruler is that they cross over: the Ruler becomes perceptive about individual human contacts, and the Doctor forgets what he has learned, and becomes Messianic.’Footnote 83 Moreover, there is an ‘irony’ in the sense that the Ruler cannot simply be characterised as an ‘idiotic fascist’: ‘On the contrary, he's a rather cultivated figure.’Footnote 84 Therefore, the Ruler emerges as a sort of ‘enlightened’ individual with an emerging sense of realisation to the predicament, whereas the Doctor loses his way completely and becomes blinded to the reality of the situation and steadily spirals downwards into a quasi-magical/mythical world.

For Davies, the complex character of the Doctor was highly appealing, and his ‘multifacetedness’ was an aspect that the composer tried to capture ‘musically, psychologically and spiritually’.Footnote 85 Certainly, the exchanges between the Doctor and the Ruler are among the most compelling moments in the whole opera,Footnote 86 and the manner in which their characters travel in opposite directions along the same continuum, crossing over in the middle, is powerfully realised musically. But composing music for characters who are in a personal state of transformation was nothing new for Davies; indeed, it is a feature that is common to his other dramatic works. In Taverner, for instance, we witness the demise of the eponymous central character as he is transformed from level-headed composer to destructive religious fanatic. For David Beard, Taverner is the ‘blueprint for Davies's obsession with dogma and transformation, established by an anti-authoritarian stance, [and] an interest in symbolism and betrayal’.Footnote 87 And for John Warnaby, The Doctor of Myddfai, rather than Resurrection, is the ‘true sequel’ to Taverner because of its ‘obvious political overtones’ and its ‘two-act form, its many characters, plus chorus and full orchestra’. Like the figure of Taverner, the Doctor is ‘driven by an inner compulsion, as he tries to grapple with the power of the state’.Footnote 88 And also like Taverner, we witness the gradual mental deterioration of the Doctor – a condition that belongs to a generic topic of madness that can be seen in other earlier operas and music-theatre pieces, such as Eight Songs for a Mad King, Miss Donnithorne's Maggot (1974) and The Lighthouse (1979), as well as the later Davies–Pountney collaboration, Mr Emmet Takes a Walk (1999). However, while Pountney thought of the libretto for The Doctor of Myddfai as ‘a kind of allegory’,Footnote 89 Davies's earlier works for stage and theatre, as Richard McGregor has pointed out, ‘tended to focus on real characters, human beings placed in extraordinary contexts’.Footnote 90 Therefore, although the opera can be interpreted as allegorical or symbolic, featuring a plot where the mythical/unreal and the factual/real are deliberately interwoven, overlaid and blurred, the main thrust of the drama is arguably visceral and powerful enough to make it appear ‘real’. Indeed, the work's curious concoction of opposites and contradictions can also be identified in earlier dramatic works by Davies that set his own libretti, and these features often manifest themselves through the figure of the Antichrist – a figure indistinguishable from the real Christ, but representing a total inversion of Christian beliefs. And even though this figure does not appear in The Doctor of Myddfai, the general notions of distinguishing the real from the unreal, the truth from falsity, sanity from insanity, and good from evil, are still unmistakably present.

A case in point concerns the Child. Even though her character, in comparison to the Doctor's or the Ruler's, is more stable and constant throughout the opera, there is some doubt as to what the future may look like under her new leadership. Although Pountney asserts that there is ‘certainly a grain of optimism at the end of the piece’, he concedes that ‘there are many strands for the music to pick up. One of them is that the knowledge of the use of plants has lain more or less dormant for a long time, and suddenly somebody who is about to be in a position of power has become reacquainted with it. That offers a possibility for both good and evil, like all types of knowledge.’Footnote 91 For Davies, the end of the opera, at the moment where the daughter pronounces herself as the new Doctor, is a ‘very touching moment towards which everything moves’: ‘Here is the innocence of the child shining out and taking the lead. There's something uncorrupted and incorruptible about that. And, all right, I'm not optimistic, but at the end of the opera in this figure of the child there is hope. It doesn't end in gloom and despair. It ends, even in the music, on a very bright and very full note.’Footnote 92 Davies's remarks here raise an interesting question: to what extent does the music provide a sense of fresh hope – of respair – at the end of the opera?

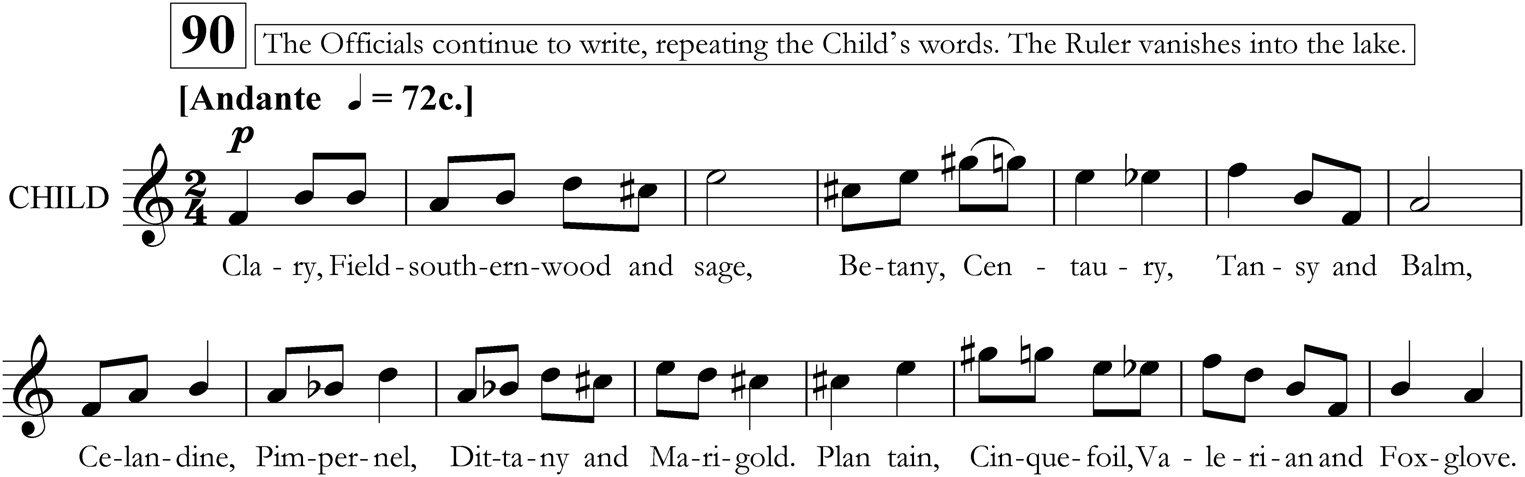

The final scene, Act II scene 3, opens with a musical evocation of the lake. Davies conjures a bewitching texture – a deep octave C on lower strings, glissando harmonics on two solo violas and cellos, and a flowing, chromatic figure on marimba (evoking the gentle ripples on the surface of the water) – that sets the scene for the entrance of the Child, signalled by her motif on harp and tuned percussion (see Example 11). The C-rooted harmony of this music strongly embodies the child's innocence and promotes hope for the future. This sentiment appears to be fulfilled, as the transference of the modal dominant F from its association with the rain in the first act to its association with the Myddfai herbal in this scene, begins with material given to the three lake maidens from Fig. 86+5: the melody here, derived from the first two sub-units of the Doctor's Luna set square, is then repeated by the Child at Fig. 90 (see Example 12). The Child's rediscovery of the healing properties of plants and flowers, and the intoning of their names (a moment which, according to Pountney, infuses the libretto with ‘lyricism’ and ‘a sense of sensuality and beauty’Footnote 93) leads eventually to Davies's ‘very bright and very full note’ – the final pitch-class B, the work's modal tonic, scored for full orchestra, covering three octaves, and rising via a slow crescendo from sffz:p to fff.

Example 11. Act II scene 3, Fig. 84.

Example 12. Act II scene 3, Fig. 90 (Child only).

But there is an alternative way to read this final scene. Firstly, we need to bear in mind the rather sinister manner in which Davies elects to set the moment where the Child, retelling the final instalment of the folktale at the end of Act II scene 1, finally makes the connection to her own lineage: ‘But she [the fairy bride in the folktale] left behind her healing power. / And all her children from that hour to this / Are Doctors of Myddfai … / That's me.’Footnote 94 Here, the music moves unexpectedly from modal D♭ to foreground the tritone A♭–D♮, accompanied by the Child's sinister laughter (Fig. 60). Secondly, the moment that the Child announces that she is the Doctor and that the war is over is overcast by the dark shadow of another tritone – this time the superimposition of the triads of B minor on strings and F minor on woodwind (Act II scene 3, Fig. 89).Footnote 95 And finally, the lead-up to Davies's ‘very bright and very full note’ is a moment, harmonically speaking, stricken with doubt and conflict; here, in a moment akin to the end of Act I, but with much more intensity, separate pitch centres are brought sharply into focus, one after the other: first B major (upper woodwind, glockenspiel and harp), then C♯ major (upper strings and crotales), then F minor (horns), and lastly the ‘Death’ chord-related A/E♭ dyad (lower woodwind, brass and strings) (see Example 3). The superimposition of these pitch centres generates a devastating dissonance – a piercing moment that serves to encapsulate the work's fundamental sense of opposition and tension – until it eventually gives way to the clarity and force of the single pitch-class B – Davies's ‘very bright and very full note’ – on full orchestra. Thus, the ending is poised on a knife-edge; its message and meaning ambiguous and left open to interpretation, offering the possibility for good or evil.

Articulating ‘Welshness’ in the opera

Writing in 1996, Pountney indicated that the commission brief for The Doctor of Myddfai ‘should contain an element of Welshness, show off the company, and celebrate its chorus’.Footnote 96 But how, exactly, is this ‘element of Welshness’ articulated in the opera?

Most obvious, of course, is the fact that the libretto is based on a Welsh folktale. But Pountney also deliberately places the action, both at the start and at the end of the opera, in ‘Zone 645’ – the government's name for Wales. Zone 645 is an abandoned fringe region, faceless and devoid of any individual identity and culture. At the start of Act I scene 2, the First Official asks the Doctor to state his business:

DOCTOR

I come from Wales.

FIRST OFFICIAL

There is no such place.

State your code and zone …

DOCTOR

I do not know such things.

… Could you not look up my zone?

FIRST OFFICIAL

All references to so-called countries

Have been officially expunged.

They were found to be divisive,

And a barrier to efficient continental policy.Footnote 97

In the face of governmental bureaucracy, negligence and oppression, the dying citizens in the opera sing two hymns in Welsh, the first by the lake (Act I scene 1) and the second outside the government's council room, the force of which breaks open one of the windows, interrupting the ministers’ meeting (Act II scene 1). The words for both hymns (written by Pountney and translated into Welsh by Elfyn JonesFootnote 98), and Davies's musical setting, allude to the rich tradition of congregational singing in Wales's nonconformist chapels (see Example 6). However, the people are spiritually as well as physically afflicted and express doubt in relation to their own religious convictions. They sing ‘Yn swrth ein meddwl, gwan ein ffydd’ (‘Our minds are numb, our faith is vague’) in the first hymn, a position that is intensified in the second by the use of the first person: ‘Megis plwm yw pwysau ’nghalon, / Megis plwm y glaw ei wedd’ (‘The rain soaked sky is leaden, / My heart weighs like a stone’).Footnote 99 Nevertheless, the hymns foster a deep sense of community and serve to tether the people – and the work – to a particular place and country, and in turn help them to a regain a sense of belonging and reclaim some of their lost cultural heritage and identity.

Another indigenous musical signifier, as already discussed, is the use of the harp to accompany the Child in Act I scene 4 (see Example 5). At least two critics at the time of the work's first performances drew attention to Davies's reference to the Welsh tradition of cerdd dant, or penillion – a form of improvised song with harp accompaniment.Footnote 100 It is noteworthy that the harmonic language for the hymns and the Child's song is predominantly modal; as a result, Davies effectively manages to allude to these Welsh musical traditions without feeling the need to resort to a parodic style characteristic of some of his earlier dramatic works. As McGregor rightly argues: ‘The stylistic cross-references which in other works are used to deliberately create a disjunction with the surrounding music (as for example the ‘pop group’ in Resurrection) are still present, but are integrated into the action in a way which is stylistically appropriate to the unfolding narrative.’Footnote 101

Davies's approach here is revealing, as it is reflected on the higher, broader plane, too. Indeed, one gets a clear sense that both composer and librettist approached the ‘Welshness’ part of the commission with much thought and consideration: here, Wales's cultural and traditional heritage is regarded with sensitivity and valued as a rich source for artistic inspiration. In short, the music and libretto, combined, serve to articulate a form of Welsh identity which manages to firmly avoid unwelcome elements of cliché and stereotype. However, the fact that the prestigious commission was awarded to a composer ‘born in Salford, now living in Scotland’ – and therefore not from the ‘west of Offa's Dyke’ – certainly raised a few eyebrows at the time.Footnote 102 Indeed, although Welsh National Opera is principally renowned for its productions of established repertoire and commitment to taking opera to a wide audience,Footnote 103 it has also shown throughout its history a dedication to commissioning new works, especially from Welsh composers. In 1953, for instance, the company staged Arwel Hughes's Menna (1950–1); this was followed by Grace Williams's The Parlour (1961) in 1966, Alun Hoddinott's The Beach of Falesá in 1974, William Mathias's The Servants in 1980, and Pwyll ap Siôn's bilingual opera Gair ar Gnawd/Word on Flesh in 2012. No doubt sensing that the commission had the potential to provoke controversy, Davies in his pre-premiere interview with Reynolds indicated that:

My father's family left North Wales in 1848 and went to the nearest industrial part they knew to find work and eventually finished up in Salford before I came on the scene. But I don't think it should be astonishing at all that somebody living in Orkney is interested in Wales because there you have a community which must have a lot in common with the Welsh in that it feels somewhat alienated from the centres … But apart from having that feeling of alienation from large cities in common, those places do exhibit an enormous indigenous culture which is of tremendous interest.Footnote 104

But Davies's interest extended beyond indigenous culture to the Welsh landscape and the specifics of place.Footnote 105 Six months prior to the first performances of the opera, Davies and Pountney paid a visit to Llyn y Fan Fach to witness the sublime setting of the lake and its surrounding areas first hand.Footnote 106 According to Geraint Owen, the rural setting of Myddfai is ‘classically Welsh’, characterised by ‘rolling green hills and pasture dotted with oak woodland’.Footnote 107 One of the central components of Pountney's plot involves the fatal disease caused by rain, quite possibly as a result of toxins being deliberately released into the atmosphere. In Pountney's dystopian scenario, Myddfai's once verdant and flourishing environment is plunged into deep crisis by human intervention. This certainly resonated with Davies's own, very close identification with the reality of environmental exploitation in the 1970s. As Karen J. Olson explains: ‘Soon after he moved to the islands, Davies became involved in Orkney's No Uranium campaign, a pro-environment antinuclear movement to block uranium mining in his new community.’Footnote 108 This resulted in Black Pentecost (1979) and The Yellow Cake Revue (1980), both of which support ‘anthropocentric environmentalism, that is, human-oriented environmental consciousness’.Footnote 109 Davies continued to champion and raise awareness of environmental issues after The Yellow Cake Revue, but the focus shifted away from the uranium debate towards climate change and global warming, as seen, for instance, in The Turn of the Tide (1993), Antarctic Symphony (2000), Last Door of Light (2008) and the Violin Concerto No. 2: Fiddler on the Shore (2009). As a result, as I have argued elsewhere, The Doctor of Myddfai can be read as a compelling environmental lament.Footnote 110 Certainly, the work tapped into the growing sense of anxiety that was being expressed in the 1990s in relation to environmental exploitation – anxiety that has become even more acute since then. In much the same way as the folktale's mark of the furrow relates the past to the present, the opera, through its engagement with environmental issues and public health and political concerns, continues to communicate powerfully and curiously directly to our own contemporary condition.

* * *

At the time of the work's premiere, Davies intimated that The Doctor of Myddfai would probably be his last opera.Footnote 111 But his creative partnership with Pountney proved to be a success, and Pountney went on to write the libretto and direct two further works for the stage – the music-theatre work Mr Emmet Takes a Walk (1999) and the opera (for student performers) Kommilitonen! (Young Blood!) (2010).Footnote 112 In June 2015, less than a year before his death, Davies attended the Savoy Hotel, London, to collect the prestigious South Bank Sky Arts Award for his Tenth Symphony: Alla ricerca di Borromini (2013). Close friend Sylvia Junge accompanied the composer that evening and recalls that in the reception beforehand, Davies and Pountney – who at the time was Artistic Director at Welsh National Opera – talked at length about reviving The Doctor of Myddfai and planned to meet at a later date to discuss matters further.Footnote 113 Regrettably, the meeting never took place and the opera has remained unstaged since 1996.