The development of Standard Austrian German (SAG; de-AT) is closely linked to the development of Standard German German (SGG; de-DE) as spoken in Northern Germany. Traditionally, SAG is strongly geared towards SGG norms. The orientation towards SGG norms goes back to at least 1750, when Maria Theresia ordered the adoption of the Upper Saxonian norms in place at that time (Ebner Reference Ebner1969, Wiesinger Reference Wiesinger and Stickel1989). Since then, SAG pronunciation is modelled on SGG and Austrian newsreaders are instructed according to the norms of Duden's (2005) Aussprachewörterbuch and Siebs (Reference Siebs, de Boor and Diels1958, with an addendum for Austria) (Wächter-Kollpacher Reference Wächter-Kollpacher, Muhr, Schrodt and Wiesinger1995, Soukup & Moosmüller Reference Soukop, Moosmüller, Kristiansen and Coupland2011). This procedure leads to an inconsistent usage of SGG features in Austrian broadcasting media (Wiesinger Reference Wiesinger, Krech, Stock, Hirschfeld and Anders2009, Soukup & Moosmüller Reference Soukop, Moosmüller, Kristiansen and Coupland2011, Hildenbrandt & Moosmüller Reference Hildenbrandt, Moosmüller, Torgersen, Hårstad, Mæhlum and Røyneland2015). Therefore, from a methodological point of view, pronunciation used in the Austrian broadcasting media is unsuitable for defining SAG (Moosmüller Reference Moosmüller2015).

Instead, some authors claim that SAG needs to be defined according to criteria of acceptability and described against the background of the social and regional characteristics extracted from the results of analyses of acceptability (see Moosmüller Reference Moosmüller1991, Soukup Reference Soukup2009, Goldgruber Reference Goldgruber2011). According to these analyses, SAG is spoken by educated speakers with an academic background. Regionally, SAG is located in the urban centres, especially Salzburg and Vienna. Educated speakers who make use of South Bavarian characteristics are not considered as speakers of SAG (Moosmüller Reference Moosmüller1991).

The present description of SAG is based on two corpora, one collected from 1984 to 1988, comprising 100 speakers,Footnote 1 and the other from 2011 to 2013, comprising 48 speakers. A smaller corpus of six speakers was collected in 2002 (Moosmüller Reference Moosmüller2007). The examples presented below are collected from a 43-year-old male speaker, born and raised in Vienna, with an academic education, who served as the model speaker. His parents were also born and raised in Vienna and have an academic education.Footnote 2

Analyses of production reveal that SAG is largely the outcome of a contact situation (Brandstätter & Moosmüller Reference Brandstätter and Moosmüller2015). SAG stands between SGG and the Middle Bavarian dialects (MBDs). MBDs form the basis of SAG pronunciation, yet the phonological system is modelled on SGG. The differences are to be found in fine phonetic details, which will be described below.

Consonants

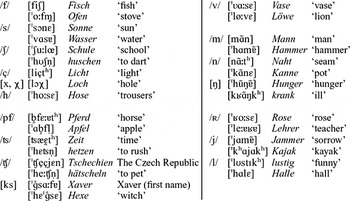

The table presents the consonant phonemes of SAG. A speaker-specific representation has to be assumed regarding the trill. The chart lists both the uvular trill and the alveolar trill. Most speakers make use of a uvular production (either trill or fricative). However, for those speakers who exclusively apply an alveolar production (either trill or approximant), /r/ has to be assumed. The chart also lists cases whose phonemic status is discussed in the literature. These are the velar nasal consonant [ŋ] (see e.g. Lass Reference Lass1984; Kohler Reference Kohler1995, Reference Kohler1999 for a phonemic status of [ŋ], see e.g. Vennemann Reference Vennemann1970, Dressler Reference Dressler and Goyvaerts1981 for an abstract analysis of [ŋ]), the affricates (see Ungeheuer Reference Ungeheuer, de Boor, Moser and Winkler1969, Kohler Reference Kohler1995 for a biphonematic analysis, Luschützky Reference Luschützky1985, Dogil & Jessen Reference Dogil, Jessen and Prinzhorn1989, Wiese Reference Wiese1996 for a monophonematic treatment; for an extensive discussion see Berns Reference Berns2013), and the complementarily distributed palatal and velar fricatives (see Dressler Reference Dressler1977; Kohler Reference Kohler1990, Reference Kohler1995; Wiese Reference Wiese1996).

In order to provide an impression of the phonological and phonetic variation present in the reading of the word lists, a narrow transcription was chosen in the illustration.

With the exception of the labiodental fricative, all obstruents are voiceless. Plosives are distinguished by aspiration (as measured by VOT) and closure duration (Moosmüller & Ringen Reference Moosmüller and Ringen2004). In formal speech styles, e.g. reading, the VOT of lenis plosives ranges between 5 ms and 20 ms; the VOT range of fortis plosives lies between 40 ms and 60 ms (Moosmüller Reference Moosmüller, Bose and Neuber2011a). In spontaneous speech, though, bilabial and alveolar fortis and lenis plosives might collapse, especially in word-initial position, so that packen ‘to pack’ and backen ‘to bake’ become homophonous: [ˈ

![]() ɑk

ɑk

![]() ].Footnote

3

Neutralisation of bilabial and alveolar plosives is a characteristic of MBDs. In the case of the velar plosive, lenition might occur before sonorants, e.g. klauben [ˈ

].Footnote

3

Neutralisation of bilabial and alveolar plosives is a characteristic of MBDs. In the case of the velar plosive, lenition might occur before sonorants, e.g. klauben [ˈ

![]() lɑ

lɑ

![]() b

b

![]() ] ‘to pick up’, Kraft [

] ‘to pick up’, Kraft [

![]() ʁɑftʰ] ‘strength’, Knie [

ʁɑftʰ] ‘strength’, Knie [

![]() niː] ‘knee’. Preceding front vowels, the velar plosive might be subjected to affrication (Moosmüller & Ringen Reference Moosmüller and Ringen2004), e.g. Kübel [ˈk

x

y:bœl] ‘bucket’. In intervocalic position, lenis plosives might be pronounced either voiced or as voiced fricatives, especially in unstressed positions, e.g. aber [ˈɑːbɐ] or [ˈɑːßɐ] ‘but’, oder [ˈoːdɐ] or [ˈoːðɐ] ‘or’, rege [ˈʀeːɡɛ] or [ˈʀeːɣɛ] ‘busy’. After nasal consonants, lenis plosives are voiced, e.g. Hunde [ˈhʊndɛ] ‘dogs’, except word-finally, e.g. Hund [hʊn

niː] ‘knee’. Preceding front vowels, the velar plosive might be subjected to affrication (Moosmüller & Ringen Reference Moosmüller and Ringen2004), e.g. Kübel [ˈk

x

y:bœl] ‘bucket’. In intervocalic position, lenis plosives might be pronounced either voiced or as voiced fricatives, especially in unstressed positions, e.g. aber [ˈɑːbɐ] or [ˈɑːßɐ] ‘but’, oder [ˈoːdɐ] or [ˈoːðɐ] ‘or’, rege [ˈʀeːɡɛ] or [ˈʀeːɣɛ] ‘busy’. After nasal consonants, lenis plosives are voiced, e.g. Hunde [ˈhʊndɛ] ‘dogs’, except word-finally, e.g. Hund [hʊn

![]() ] or [hʊntʰ] ‘dog’.

] or [hʊntʰ] ‘dog’.

The labiodental fricative /v/ is mostly pronounced as an approximant [ʋ]. In intervocalic position, /s/ might be voiced, e.g. Reise [ˈʀa

![]() zɛ] ‘journey’. The velar fricative [x] alternates with [χ], an alternation that has also been described for SGG (Kohler Reference Kohler1990). However, in SAG, [x] is also observed after [ɔ], i.e. the distribution of the velar and the uvular fricative is less clear-cut in SAG than in SGG (for comparison, see the realisations of Koch ‘cook’ and Loch ‘hole’ in the list of examples above). Generally, orthographic <h> is not pronounced in word-medial, unstressed position, e.g. Ehe [ˈeːɛ]Footnote

4

‘marriage’.

zɛ] ‘journey’. The velar fricative [x] alternates with [χ], an alternation that has also been described for SGG (Kohler Reference Kohler1990). However, in SAG, [x] is also observed after [ɔ], i.e. the distribution of the velar and the uvular fricative is less clear-cut in SAG than in SGG (for comparison, see the realisations of Koch ‘cook’ and Loch ‘hole’ in the list of examples above). Generally, orthographic <h> is not pronounced in word-medial, unstressed position, e.g. Ehe [ˈeːɛ]Footnote

4

‘marriage’.

The alveolar nasal consonant /n/ is usually subjected to both regressive and progressive place assimilation, e.g. anbeten [ˈɑm

![]() eː

eː

![]()

![]() ] ‘to worship’, Anfahrt [ˈɑɱfɑːt]Footnote

5

‘approach’, Angeber [ˈɑŋɡeːbɛ

] ‘to worship’, Anfahrt [ˈɑɱfɑːt]Footnote

5

‘approach’, Angeber [ˈɑŋɡeːbɛ

![]() ] ‘braggart’, geben [ˈ

] ‘braggart’, geben [ˈ

![]() eːb

eːb

![]() ] ‘to give’, kaufen [ˈkɑ

] ‘to give’, kaufen [ˈkɑ

![]() f

f

![]() ] ‘to buy’, Regen [ˈʀeːɡ

] ‘to buy’, Regen [ˈʀeːɡ

![]() ] ‘rain’.

] ‘rain’.

SAG features a wide variety of realisations of the trill. In approximately the past 40 years, the pronunciation norm has changed from an alveolar to a uvular trill. The latter is mostly pronounced as a fricative, either voiced or voiceless. Alveolar trills are still in use, mostly pronounced as an approximant. In final position and before consonants, the /ʀ/ is vocalised to either [

![]() ] or [ɐ], e.g. Vater [ˈfɑːtɛ

] or [ɐ], e.g. Vater [ˈfɑːtɛ

![]() ] or [ˈfɑːtɐ] ‘father’ or Kirche [ˈkɪ

] or [ˈfɑːtɐ] ‘father’ or Kirche [ˈkɪ

![]() xɛ]Footnote

6

‘church’. Preceding /ʀ/, the vowel quality of [+constricted]Footnote

7

vowels usually changes to [–constricted], before r-vocalisation takes place, e.g. Moor [mɔ

xɛ]Footnote

6

‘church’. Preceding /ʀ/, the vowel quality of [+constricted]Footnote

7

vowels usually changes to [–constricted], before r-vocalisation takes place, e.g. Moor [mɔ

![]() ]Footnote

8

‘bog’. Reduction of the sequence er to [ɐ] is only allowed in unstressed prefixes, e.g. verkaufen [fɛ

]Footnote

8

‘bog’. Reduction of the sequence er to [ɐ] is only allowed in unstressed prefixes, e.g. verkaufen [fɛ

![]() ˈkɑ

ˈkɑ

![]() f

f

![]() ] or [fɐˈkɑ

] or [fɐˈkɑ

![]() f

f

![]() ] ‘to sell’. However, reduction to [ɐ] is not allowed in prefixes without consonantal onset, e.g. erlauben [ɛ

] ‘to sell’. However, reduction to [ɐ] is not allowed in prefixes without consonantal onset, e.g. erlauben [ɛ

![]() ˈlɑ

ˈlɑ

![]() b

b

![]() ]Footnote

9

‘to allow’. Following /ɑ/, /ʀ/ is vocalised as well, however, the result of vocalisation, [

]Footnote

9

‘to allow’. Following /ɑ/, /ʀ/ is vocalised as well, however, the result of vocalisation, [

![]() ], is absorbed, e.g. Parlament [pɑːlɑˈmɛnt] ‘parliament’, rar [ʀɑː] ‘scarce’. In intervocalic position, /ʀ/ is preserved. Again, in case of a preceding [+constricted] vowel, a change in vowel quality takes place and [

], is absorbed, e.g. Parlament [pɑːlɑˈmɛnt] ‘parliament’, rar [ʀɑː] ‘scarce’. In intervocalic position, /ʀ/ is preserved. Again, in case of a preceding [+constricted] vowel, a change in vowel quality takes place and [

![]() ] emerges, e.g. Lehrer [ˈlɛ

] emerges, e.g. Lehrer [ˈlɛ

![]() ʀɐ] ‘teacher’.

ʀɐ] ‘teacher’.

The vocalisation of the lateral is a process of MBDs which might be applied in SAG. In most varieties of MBDs, front vowels preceding /l/ are rounded. The lateral is vocalised to [

![]() ] after rounded vowels. In the case of front rounded vowels, the vocalised lateral [

] after rounded vowels. In the case of front rounded vowels, the vocalised lateral [

![]() ] is absorbed by the preceding vowel, whereas it is preserved after back rounded vowels. It has to be emphasised that l-vocalisation in SAG is restricted to unstressed positions and to high frequent words, as in e.g. also [ɔ

] is absorbed by the preceding vowel, whereas it is preserved after back rounded vowels. It has to be emphasised that l-vocalisation in SAG is restricted to unstressed positions and to high frequent words, as in e.g. also [ɔ

![]() so] ‘also’ or halt [hɔ

so] ‘also’ or halt [hɔ

![]()

![]() ] ‘just’.

] ‘just’.

Vowels

In SAG, 13 vowels are distinguished. They are plotted here on the conventional vowel chart.Footnote 10

The vowels are best described with respect to their location of constriction,Footnote 11 tongue height, and rounding. Compared to the e-vowels and their rounded cognates, the i-vowels and their rounded cognates hold a more fronted constriction location. Therefore, /i/ and /e/ are distinguished by horizontally moving the tongue from a mid-palatal to a pre-palatal position, without considerable changes in tongue height. Acoustically, this difference is reflected by an approximation of F3 and F4 in the case of /i/, and an approximation of F2 and F3 in the case of /e/ (Stevens Reference Stevens1999: 277f.). The front vowels are subdivided into unrounded and rounded; the vowels on the right of the front-vowels cluster denote the rounded cognates, the vowels on the left of the front-vowels cluster denote the unrounded cognates. For the back vowels, X-ray studies on vowel articulation proved that a retraction of the tongue is needed to form a constriction in the upper pharynx for /o/ and /ɔ/ and in the lower pharynx for /ɑ/, while /u/ and /ʊ/ are articulated in the region of the soft palate (see e.g. Fant Reference Fant1965; Straka Reference Straka and Wängler1978; Wood Reference Wood1979, Reference Wood1982).Footnote 12

The intermediate position of SAG, between MBDs and SGG, is most apparent in the articulation of high vowels. Whilst MBDs distinguish high vowels by quantity, i.e. /iː i uː u/,Footnote

13

in SGG, they are distinguished by quality, i.e. /i ɪ y ʏ u ʊ/. Primary quantity distinction is assumed for the vowel /ɑ(ː)/ (Jessen et al. Reference Jessen, Marasek, Schneider and Clahßen1995, Simpson Reference Simpson1998). Since SAG is geared towards SGG, high vowels are distinguished by quality as well. However, only a few speakers are able to consistently sustain this distinction, as already observed over a century ago by Luick (Reference Luick1904, see also Wiesinger Reference Wiesinger, Krech, Stock, Hirschfeld and Anders2009). Most speakers, with speaker-specific differences, tend to neutralilze /i/ and /ɪ/, especially in velar context (Brandstätter & Moosmüller Reference Brandstätter and Moosmüller2015; for an articulatory analysis see Harrington, Hoole & Reubold Reference Harrington, Hoole and Reubold2012). Similar results have been obtained for the high vowel pairs /y–ʏ/ and /u–ʊ/ (Brandstätter, Kaseß & Moosmüller 2015). The model speaker produces [+constricted] high vowels in Mitte [ˈmitɛ] ‘center’, Fisch [fiʃ] ‘fish’, Licht [liçtʰ] ‘light’ (see examples illustrating consonants above), and Bus [

![]() usː] ‘bus’ (see examples illustrating vowels above).

usː] ‘bus’ (see examples illustrating vowels above).

A similar situation is to be found regarding the vowels /e/ and /ɛ/. In MBDs, the development of Middle High German ë led to a situation which was termed e-confusion in traditional dialectology (Kranzmayer Reference Kranzmayer1956, Scheuringer Reference Scheuringer1990). In the Viennese dialect, since the late 1960s, a merger of expansion is observed with regard to the e-vowels (Seidelmann Reference Seidelmann1971, Moosmüller Reference Moosmüller, Dziubalska-Kołaczyk and Dębowska-Kozłowska2011b), which has also spread to the western parts of Austria, e.g. Salzburg (Moosmüller & Scheutz Reference Moosmüller, Scheutz, Auer, Reina and Kaufmann2013). Muhr (Reference Muhr2007: 41) claims that in SAG, the quality of the open-mid vowel [ɛ] is rather closed and proposes to symbolise this vowel with [

![]() ]. In our data, we observed a speaker-specific treatment of this opposition. Most speakers distinguish /e/ and /ɛ/ according to SGG norms but some speakers make no clear distinction between these vowels; /ɛ/ is sometimes pronounced as [e], and /e/ is sometimes pronounced as [ɛ].

]. In our data, we observed a speaker-specific treatment of this opposition. Most speakers distinguish /e/ and /ɛ/ according to SGG norms but some speakers make no clear distinction between these vowels; /ɛ/ is sometimes pronounced as [e], and /e/ is sometimes pronounced as [ɛ].

Long /ɛː/, as exemplified by Käfer [ˈkeːfɐ] ‘beetle’, is still assumed by Iivonen (Reference Iivonen1987). In our material, however, /ɛː/ has completely merged with /e/ (Moosmüller Reference Moosmüller2007: 52).

With the exception of [ɐ],Footnote

14

which is the result of r-vocalisation, full vowels occur in unstressed positions, a further trait of MBDs. /e/, as in e.g. the prefixes be- or ge-, is pronounced [e], e.g. betrunken [

![]() eˈtʁʊŋk

eˈtʁʊŋk

![]() ] ‘drunken’ or gekauft [

] ‘drunken’ or gekauft [

![]() eˈkɑ

eˈkɑ

![]() ft] ‘bought’, and unstressed /ɛ/ is pronounced as [ɛ], e.g. Sonne [ˈsɔnɛ] ‘sun’ or Tische [ˈtɪʃɛ] ‘tables’. Reduced vowels, as exemplified in the transcribed passage below, are extremely rare. In labial context, unstressed /e ɛ/ might be rounded, as exemplified in Sippe [ˈsɪp

ft] ‘bought’, and unstressed /ɛ/ is pronounced as [ɛ], e.g. Sonne [ˈsɔnɛ] ‘sun’ or Tische [ˈtɪʃɛ] ‘tables’. Reduced vowels, as exemplified in the transcribed passage below, are extremely rare. In labial context, unstressed /e ɛ/ might be rounded, as exemplified in Sippe [ˈsɪp

![]() ] ‘clan’, Schule [ˈʃuːlœ] ‘school’, Hüte [ˈhyːt

] ‘clan’, Schule [ˈʃuːlœ] ‘school’, Hüte [ˈhyːt

![]() ] ‘hats’, or Hütte [ˈhʏ

] ‘hats’, or Hütte [ˈhʏ

![]() ː

ː

![]() ] ‘hut’.

] ‘hut’.

However, another MBDs process, namely the deletion of the vowel /e/ in the prefix <ge-> might occur in SAG spontaneous speech. As a typical feature of especially young SAG speakers, this process is applied in, e.g. gesagt ‘said’, which is reduced to [

![]() sɑːkt]. It has to be noted, however, that, contrary to MBDs, the quality of the stressed vowel /ɑ/ is preserved, whereas MBDs would demand /ɔ/.

sɑːkt]. It has to be noted, however, that, contrary to MBDs, the quality of the stressed vowel /ɑ/ is preserved, whereas MBDs would demand /ɔ/.

Diphthongs

Three diphthongs are distinguished in SAG: /a

![]() ɑ

ɑ

![]() ɔ

ɔ

![]() /.

/.

Diphthongs exhibit a large range of realisation variants. Ulbrich (Reference Ulbrich, Krech and Stock2003), who performed an auditive analysis of five Austrian newsreaders, counted 23 different realisations of the diphthong /a

![]() /, ranging from [a

/, ranging from [a

![]() ] to monophthongised [ɛ], 19 different realisations of the diphthong /ɑ

] to monophthongised [ɛ], 19 different realisations of the diphthong /ɑ

![]() /, ranging from [a

/, ranging from [a

![]() ]Footnote

15

to monophthongised [ɔ], and 23 different realisations of the diphthong /ɔ

]Footnote

15

to monophthongised [ɔ], and 23 different realisations of the diphthong /ɔ

![]() /, ranging from [ɔ

/, ranging from [ɔ

![]() ] to monophthongised [ɔ].Footnote

16

Similar results have been obtained in our data of Viennese SAG speakers (Vollmann & Moosmüller Reference Vollmann and Moosmüller1999, Moosmüller & Vollmann Reference Moosmüller and Vollmann2001). As an influence of the Viennese monophthongisation, which affected the Viennese dialect and changed the diphthongs /a

] to monophthongised [ɔ].Footnote

16

Similar results have been obtained in our data of Viennese SAG speakers (Vollmann & Moosmüller Reference Vollmann and Moosmüller1999, Moosmüller & Vollmann Reference Moosmüller and Vollmann2001). As an influence of the Viennese monophthongisation, which affected the Viennese dialect and changed the diphthongs /a

![]() / and /ɑ

/ and /ɑ

![]() /Footnote

17

to /æː/ and /ɒː/, respectively, a tendency to assimilate the onset of the diphthong to the offset can also be observed in the Viennese variant of SAG. Assimilation regarding tongue height can be observed in the case of /a

/Footnote

17

to /æː/ and /ɒː/, respectively, a tendency to assimilate the onset of the diphthong to the offset can also be observed in the Viennese variant of SAG. Assimilation regarding tongue height can be observed in the case of /a

![]() / → [æ

/ → [æ

![]() ]. In the case of /ɑ

]. In the case of /ɑ

![]() /, rounding of the onset might take place, resulting in [ɒ

/, rounding of the onset might take place, resulting in [ɒ

![]() ], and in the case of /ɔ

], and in the case of /ɔ

![]() /, delabialisation of the onset might occur, resulting in [ʌ

/, delabialisation of the onset might occur, resulting in [ʌ

![]() ]. It should be noted that in SAG, monophthongisation is restricted to unstressed positions.

]. It should be noted that in SAG, monophthongisation is restricted to unstressed positions.

Prosody

Intonation

Standard Austrian German is an intonation language. To convey postlexical meanings at a suprasegmental level, the prosodic parameters f0, duration, and amplitude are used (Wunderli Reference Wunderli1981: 292).

Intonation units are distinguished primarily by final syllable-lengthening and by resetting f0 between two intonation units. SAG shows an overall tendency of the f0 contour to gradually drift downwards over the course of an utterance, between a declining top line connecting the f0 peaks and a declining baseline connecting the f0 valleys. Imperative sentences have a higher and longer initial f0 (the nucleus contour is mostly H* or H*+^H; H*+L occurs less frequently) and a lower final f0 than declaratives, questions, and continuative utterances. This results in a higher mean f0 and a stronger overall declination. Declarative sentences show a negative overall slope as well, but it is weaker and restricted to the second half of the utterance. The nucleus contour of declaratives is mostly L*+H. Monotonal L* occurs more rarely. In most cases, partial questions are also pronounced with a declining f0, but they can also have the rising final contour typical of yes–no-questions. In yes–no-questions, the overall f0 movement is rising, although a negative slope in the first half of the utterance is common. The initial f0 and the mean f0 are higher in yes–no-questions than in declarative sentences. The final rise takes place mainly in the second half of the utterance, and the target point is the highest within the utterance. H*+^H is the most common nucleus contour, although L*+H can be observed as well. Like yes–no-questions, continuative utterances also have a final rise with the highest utterance frequency as target point, and, furthermore, they have the same nucleus contours H*+^H and L*+H. However, unlike yes–no-questions, mean f0 in continuative utterances is as low as in declaratives, the overall f0 contour is relatively flat, and the final rise has a smaller f0 range.Footnote 18

In a cross-linguistic study of the intonation of read declarative sentences in Standard varieties of German, Ulbrich (Reference Ulbrich2005) found some gradual differences between SAG and SGG. Her results suggest that compared to SGG, in SAG speakers make more and longer sentence-internal pauses. Moreover, speaking rate is lower and the f0 range over the means of all peaks and valleys within an utterance is larger. SAG also shows greater quantitative differences between accentuated and unaccentuated syllables, the former exhibiting longer duration. In pre-nuclear high tones and nuclear L*+H syllables, f0 range of rising f0 is larger in SAG than in SGG. Additionally, there is a steeper fall from a high-nucleus syllable.

In the realisation of information structure, duration, amplitude, and relative height of the focus peak are gradually increased with narrowing focus, while the mean f0 over the utterance decreases. In narrow contrastive focus, a high peak can be observed shortly before the focused word, followed by a steep fall, resulting in either <H*+L or <H+L* (Schmid & Moosmüller Reference Schmid and Moosmüller2013).

Word stress

Like SGG, SAG has variable word stress, which depends on morphological rules. Mostly, stress is realised on the lexical root, and, consequently, often on the first syllable. Affixes can either be stressed or unstressed. In compounds, stress usually falls on the first syllable. Additional syllables can have secondary stress. The position of word stress may have a distinctive function. It can be grammatically distinctive, e.g. ˈPerfekt ‘perfect (ling.), n’ and perˈfekt ‘perfect, adj’, or semantically distinctive, e.g. ˈübersetzen ‘to ferry across a river’ vs. überˈsetzen ‘translate’. Some stress placements differ from SGG, e.g. Kaˈffee ‘coffee’ or Taˈbak ‘tobacco’ (see Wiesinger Reference Wiesinger, Krech, Stock, Hirschfeld and Anders2009 for an overview).

Acoustic analysis of stressed and unstressed vowels in disyllabic words in nucleus position shows that SAG as well as SGG use f0, duration, intensity, and vowel quality (formants) to convey word stress. However, different tendencies are observed between the two language varieties, especially concerning f0 and formants: SAG speakers realise the unstressed vowels more often with higher f0 values than the preceding stressed vowels. Especially in the realisations of male speakers, formant values of stressed and unstressed e-vowels largely overlap. Unstressed vowels often preserve a full vowel quality.

Transcription of ‘The north wind and the sun’

Acknowledgements

The study was performed within the project ‘Gehobenes Deutsch in Österreich’, funded by the FWF from 1984 to 1988, and within the project I 536-G20 ‘Vowel tensity in Standard Austrian and Standard German’, funded by the FWF from 2011 to 2013. We are grateful for the helpful comments of three anonymous reviewers on an earlier version of the paper.