Introduction

Anaphora resolution research has investigated the process of resolving pronouns or noun phrases (NPs) to earlier or later items in the discourse, mainly focusing on the division of labor between null and overt pronouns in null-subject languages. In comprehension, studies on Italian have demonstrated that speakers have a clear preference for interpreting null pronouns as referring to subject antecedents (i.e., Marta in (1)), whereas overt pronouns are more likely to be referred to nonsubject antecedents (i.e., Piera in (1)).

“Marta wrote to Piera often when pro/she was in France”

This pattern of interpretation has been explained by Calabrese (Reference Calabrese, Fukui, Rapoport and Sagey1986), assuming that pro looks for an antecedent which is the “Subject of predication” or “Thema,” which is in turn the “expected” antecedent under the assumption that speakers are inclined to keep talking about the same referent. Carminati (Reference Carminati2002)’s Position of Antecedent Hypothesis (PAH) claims that in Italian null-subject pronouns corefer with antecedents in the specifier of the inflectional phrase (IP), and overt pronouns refer to antecedents lower in the clause.

The interpretation preferences in Spanish are less clear, with some studies reporting a subject antecedent preference for null pronouns and a weaker nonsubject preference for overt pronouns in comparison to Italian (Filiaci et al., Reference Filiaci, Sorace and Carreiras2014). In contrast, more recent research has demonstrated that in Spanish, in a specific clausal environment, null pronouns may refer to either subject or nonsubject antecedents, with no clear preference (e.g., Chamorro, Reference Chamorro2018; Chamorro et al., Reference Chamorro, Sorace and Sturt2016).

Previous research has compared Spanish and Italian anaphora resolution under the untested assumption that the two languages have comparable use of null and explicit pronouns (e.g., Filiaci et al., Reference Filiaci, Sorace and Carreiras2014). However, it is unclear from the existing corpus studies whether differences in the interpretation of anaphora may be linked to production patterns. The present study aims at contributing to fill this gap by comparing Italian and Spanish on comprehension and production.

Anaphora resolution in Italian and the PAH

Experimental work in Italian by Carminati (Reference Carminati2002) demonstrated that, in complex sentences, a null pronoun (pro) is interpreted in coreference with an antecedent in a prominent syntactic position (SpecIP), whereas an overt pronoun looks for an antecedent in a nonprominent syntactic position, a pattern of interpretation explained with the PAH. Carminati ran a series of experiments testing Italian anaphoric pronouns to test the validity of the PAH. For example, in a self-paced reading experiment, the author included sentences with a subordinate clause introducing subject and object referents followed by a main clause where either a null or an explicit pronoun was present, as illustrated in (2). The content of the main clause was semantically biased to allow subject (2.a) or object (2.b) disambiguation:

After Giovanni embarrassed Giorgio in front of everyone, Ø/he apologized repeatedly/felt offended.

In line with the PAH, Carminati observed faster reading times for null pronouns when they were disambiguated toward the subject in comparison to object disambiguation. Conversely, the author found that overt pronouns disambiguated toward the preceding object were read faster than those that were disambiguated toward the subject.Footnote 1 According to Carminati, the biases observed for pronoun interpretation in Italian are based on pragmatic principles. As claimed by Ariel (Reference Ariel1990, Reference Ariel, Sanders, Schilperoord and Spooren2001), the use of referring expressions is based on assessment of prominence of the antecedent and content of the referential expression. For example, a referring expression that is less conspicuous in terms of informativity, rigidity, and attenuation (such as a null pronoun) is likely to refer to a more prominent antecedent in the preceding discourse (i.e., the subject), in comparison to a referring expression that is more conspicuous (i.e., an overt pronoun). While there is still some disagreement in the literature regarding the factors that determine the prominence of discourse entities (Arnold, Reference Arnold2010, for a review), according to Carminati, structural positions have a clear association with prominence in Italian: more specifically, the SpecIP position carries more prominence than lower positions.

While Carminati (Reference Carminati2002) only analyzed anaphoric pronouns in Italian, Sorace and Filiaci (Reference Sorace and Filiaci2006) manipulated the position of the pronoun, testing the interpretation of overt/null pronouns preceding their antecedent (i.e., cataphoric pronouns, as in (3b)), and overt/null pronouns following their antecedent (i.e., anaphoric pronouns (3a)).

When pro/she crosses the road, the old lady greets the girl

For anaphoric pronouns (3.a), Sorace and Filiaci found 51% subject interpretations for null pronouns and 82% object interpretations for overt pronouns. For cataphoric pronouns (3.b), the authors found that the preference for subject antecedents in the case of null pronouns was 85%. Italian speakers also showed a preference for external referent interpretations for overt cataphoric pronouns (i.e., someone else not mentioned in the context: 64%), whereas object references for cataphoric pronouns amounted to 24%.Footnote 2

Anaphora resolution in Spanish and previous comparative research

Italian and Spanish use similar syntactic strategies to encode the information structure of a sentence, which in turn can affect how prominence is established in the discourse (see Filiaci et al. Reference Filiaci, Sorace and Carreiras2014, for a review). Despite the typological relatedness and the similarities at the level of information structure, previous studies on anaphora resolution have questioned the validity of the PAH to explain the interpretation of null and overt subjects in Spanish. Two studies have used the self-paced reading technique to test intrasentential anaphora resolution in semantically biased sentences (Filiaci et al., Reference Filiaci, Sorace and Carreiras2014; Keating et al., Reference Keating, Jegerski and VanPatten2016). Keating et al. (Reference Keating, Jegerski and VanPatten2016) measured subject and object antecedents’ preferences for Mexican-Spanish speakers, using sentences like (4).

After the policeman/the suspect spoke with the suspect/the policeman, pro/he admitted his guilt

While Keating et al. found a preference for null-subject pronouns to be resolved toward subject antecedents and for overt pronouns to be resolved toward object antecedents, the significance of the effects was not consistent across all measures and was partly limited to the analyses by participants. Thus, the authors were cautious in interpreting their results as supporting the PAH (Carminati, Reference Carminati2002). The validity of the PAH for Spanish has been challenged by Filiaci et al. (Reference Filiaci, Sorace and Carreiras2014), who compared the preferred interpretations of null- and overt-subject pronouns in Italian and Spanish with a self-paced reading task, using similar sentences as Keating et al. (Reference Keating, Jegerski and VanPatten2016). Filiaci et al. (Reference Filiaci, Sorace and Carreiras2014) found that Spanish and Italian speakers were equally fast at processing a null pronoun that referred to a subject antecedent and experienced the same processing cost when a null pronoun coreferred with an object antecedent. However, Spanish-speaking participants did not experience the same processing penalty as Italian speakers when an overt pronoun coreferred with a subject antecedent (see Keating et al., Reference Keating, VanPatten and Jegerski2011, for similar results on Spanish using an offline sentence comprehension task).

A study by Chamorro et al. (Reference Chamorro, Sorace and Sturt2016) tested anaphora resolution in Peninsular Spanish using an offline naturalness judgment task and an eye-tracking task during reading. Participants were presented with main–subordinate sentences like (5) and (6) in which a null or overt pronoun referred to a subject or an object antecedent, based on number cues disambiguation:

The mothers greeted the girl when she crossed a street with a lot of traffic.

The mother greeted the girls when she crossed a street with a lot of traffic.

Chamorro et al. (Reference Chamorro, Sorace and Sturt2016) found that Peninsular-Spanish speakers had a clear preference for the object as the antecedent of an overt pronoun. However, when participants were presented with a null pronoun matching either a subject or an object antecedent, the authors did not find a significant difference in ratings or eye-movement measures, showing a lack of subject bias (see Chamorro, Reference Chamorro2018, for similar results). It is worth noting that, in main–subordinate sentences, less clear results concerning the subject bias of the null pronoun have been shown for Italian as well (see footnote 2). Hence, it is not clear whether the lack of subject bias for the null pronoun in Spanish may reflect a difference between Italian and Spanish, or it may be an effect of clause order (Chamorro, Reference Chamorro2018, p. 13).

A study by Contemori et al. (Reference Contemori, Asiri and Perea Irigoyen2019) used main–subordinate (7a) order and subordinate–main (7b) order with explicit pronouns to test the interpretation preferences of Mexican-Spanish speakers. However, in contrast with previous research, the subordinate–main order included only overt cataphoric pronouns. While for cataphoric overt pronouns, participants’ preferences were equally distributed among subject, object, and external referent choices (7b), no preference for the subject/object referent was found for anaphoric explicit pronouns (7a). Notice also that in Contemori et al., no counterbalancing with null pronouns was present, which may have affected participants’ responses (see Fernandes et al., Reference Fernandes, Luegi, Correa, de la Fuente and Hemforth2018).

While she was in high school, Yolanda met Josefina

Finally, in a study looking at Spanish spoken by Catalan–Spanish bilinguals, Bel and García-Alcaraz (Reference Bel, García-Alcaraz, Judy and Perpiñán2015) found a preference for null pronouns to refer to subject antecedents and for overt pronouns to refer to object antecedents, an effect that was particularly strong in subordinate–main order compared to the main–subordinate order (see Bel et al., Reference Bel, Sagarra, Comínguez and García-Alcaraz2016, for similar results).

Table 1 summarizes the studies on anaphora resolution in Spanish described here.

Table 1. Results of studies looking at intrasentential anaphora in Spanish

Note. The table summarizes if the results support the position of antecedent hypothesis (PAH).

Although dialectal variation may exist, we can exclude that the mixed findings on anaphora resolution research may only be due to the type of variety of Spanish spoken by participants (e.g., Peninsular vs. Mexican). In fact, most of the mixed evidence in Spanish currently pertains the Peninsular variety (Bel & García-Alcaraz, Reference Bel, García-Alcaraz, Judy and Perpiñán2015; Bel et al., Reference Bel, Sagarra, Comínguez and García-Alcaraz2016; Chamorro, Reference Chamorro2018; Chamorro et al., Reference Chamorro, Sorace and Sturt2016; Filiaci et al. Reference Filiaci, Sorace and Carreiras2014). We will come back to the factors that may influence anaphora resolution in Spanish in the Discussion section.

Comparing comprehension and production of null/overt pronouns

Comprehension and production of referring expressions are strongly connected domains that may vary across closely related languages. European and Brazilian Portuguese are an example of how referential production patterns are connected to anaphora resolution biases. To illustrate, frequency of null pronoun use is higher in European than Brazilian Portuguese, whereas the opposite is observed for overt pronouns (e.g., Barbosa et al., Reference Barbosa, Duarte and Kato2005, report a rate of overt pronoun in Brazilian Portuguese of 56% and 22% in European Portuguese). In line with the different frequency of use of null/overt pronouns, speakers of the two varieties differ on their anaphoric interpretation strategies. For example, as shown by Fernandes et al. (Reference Fernandes, Luegi, Correa, de la Fuente and Hemforth2018), European-Portuguese speakers are less likely to refer a null pronoun to an object antecedent than an explicit pronoun (null pronouns interpreted as objects: 21% vs. overt pronouns interpreted as objects: 76%), whereas Brazilian-Portuguese speakers’ choices demonstrate a less clear-cut pattern (null pronouns interpreted as objects: 26% vs. explicit pronouns interpreted as objects: 46%) (see also Corrêa, Reference Corrêa1998, a.o.).

Even though Italian and Spanish are typologically related, we do not know if differences in anaphora resolution biases can be explained in terms of different production preferences in the two languages. To our knowledge, only one study has compared Italian and Spanish anaphora resolution, demonstrating similar interpretation of null pronouns and different interpretation for overt pronouns (Filiaci et al. Reference Filiaci, Sorace and Carreiras2014). In their study, Filiaci et al. have assumed that Italian and Spanish present similar rates of pronoun production. However, production studies on Italian are hardly comparable to those on Spanish. For instance, a corpus study by Lorusso et al. (Reference Lorusso, Caprin, Guasti, Brugos, Clark and Seungwan Ha2005) cited by Filiaci et al. (Reference Filiaci, Sorace and Carreiras2014) reports a rate of overt subjects produced in Italian that includes both explicit NPs and overt pronouns (36.3%). Because Lorusso et al. did not differentiate between overt-subject pronouns and overt-subject NPs in their corpus analysis of Italian, we cannot assess the comparability of Italian and Spanish in the production domain. Belletti et al. (Reference Belletti, Bennati and Sorace2007) report a 4% overt pronouns rate in the productions of a group of Italian native speakers, whereas Di Domenico and Baroncini (Reference Di Domenico and Baroncini2019) report a 6% overt pronouns rate. It is worth noting, however, that both studies counted only third-person subject anaphoric pronoun, and as such are not directly comparable to the rates reported for Spanish by existing corpus studies that have included additional persons/numbers. Consequently, we cannot exclude that interpretation biases may correlate with a different use of referential forms in Italian and Spanish, as in European and Brazilian Portuguese.

Our study has implications for linguistic and psycholinguistic theories that link comprehension and production. For example, probabilistic models of reference (e.g., Arnold, Reference Arnold1998; Kehler et al., Reference Kehler, Kertz, Rohde and Elman2008) assume that production patterns drive interpretation. As shown by Fernandes et al. for European and Brazilian Portuguese, exposure to sentences containing a higher number of overt pronouns increased comprehenders’ interpretation toward the object antecedent. Crucially, in Fernandes et al., Brazilian-Portuguese speakers showed more adaptation than European-Portuguese speakers over the course of the experiment, integrating prior statistical knowledge (high frequency of explicit pronouns interpreted toward subject antecedents) with the knowledge obtained in the experiment.

Similar biases in the use and comprehension of pronouns are expected also under linguistic accounts, hypothesizing that antecedent’s retrieval properties (together with semantic, syntactic, morphological, and phonological ones) are coded in the pronoun itself, driving both interpretation and production (e.g., Cardinaletti & Starke, Reference Cardinaletti, Starke and van Riemsdijk1999).

Finally, comprehension and production are expected to converge in adult speakers under the asymmetric grammar approach (Koster et al., Reference Koster, Hoeks, Hendriks, Grimm, Müller, Hamann and Ruigendijk2011). According to Koster et al. (Reference Koster, Hoeks, Hendriks, Grimm, Müller, Hamann and Ruigendijk2011), the grammar consists of direction-sensitive constraints that only have an effect on the output in production but not in comprehension, or vice versa. In the case of pronouns, an example of a constraint relevant for production is that pronouns are preferred to explicit forms such as full NPs, whereas a constraint relevant for comprehension is that less informative forms refer to the most prominent antecedent. While a constraint-based grammar would generate asymmetries between comprehension and production, adult speakers and comprehenders are expected to have the cognitive resources necessary to take into account the listener’s perspective, allowing them to decide on the best choice for production or interpretation of a referring expression (e.g., pronouns are preferred for production, but if the listener cannot interpret a pronoun in discourse, the speaker will choose a more explicit form).

The present study

Previous studies on Spanish anaphora resolution have looked at different varieties (Peninsular and Mexican), using various sentence contexts (main–subordinate and subordinate–main) and experimental methodologies (offline vs. online), leading to mixed results. Thus, it is still debated if the PAH can explain anaphora resolution preferences in Spanish. In addition, there is currently no comprehensive study that compared comprehension and production of referring expressions in Spanish and Italian (see Giannakou & Sitaridou Reference Giannakou and Sitaridou2020, for a comparison of Spanish and Greek in comprehension and production). Here, we analyze a variety of Mexican Spanish spoken in Ciudad Juárez, a city bordering the US.Footnote 3 Although we do not seek to generalize the findings across other varieties of Spanish, we aim to understand if there are differing preferred interpretations between null- and explicit-subject pronouns in this variety to assess the validity of the PAH for Spanish. In addition, to further clarify the role that overt and null pronouns have in comprehension, we first compare anaphora resolution biases with production preferences. In summary, the present study aims to address the following research questions:

-

(i) Is there a clear differing preferred interpretation between null- and explicit-subject pronouns in Italian and Spanish, that is, can the PAH explain anaphora resolution biases in the two languages?

-

(ii) Is the differing preferred interpretation comparable, or do the two languages differ on the interpretation of null- and overt-subject pronouns?

-

(iii) Are these differences linked to production preferences?

To this end, we conducted one comprehension (Experiment 1) and two production studies (Experiments 2 and 3) to compare Italian and Spanish anaphora resolution and choice of referring expressions.

Experiment 1: Comprehension

Participants

Thirty-three native speakers of Italian (mean age = 25; SD = 3; range = 20–30; females = 22) were recruited at the Università per Stranieri di Perugia in Italy. Participants were undergraduate and graduate students at the time of testing. The Italian speakers reported that they were born in Italy and that Italian was their native language. Italian speakers were late learners of additional languages (English, French, Spanish, Chinese, and Japanese).

Thirty-three speakers of Mexican Spanish (mean age = 23; SD = 4; range = 20–28; females = 18) were undergraduate students at the Universidad Autónoma de Ciudad Juárez in Mexico. The Mexican-Spanish speakers were born in Mexico and reported knowledge of English as a second language learned after age 6 at the intermediate level of proficiency.Footnote 4

Materials

Participants completed a sentence comprehension task that consisted of reading sentences and answering comprehension questions (e.g., Chamorro Reference Chamorro2018). Thirty-two semantically neutral sentences with intrasentential anaphora were created in Italian and translated in Mexican Spanish. The semantic neutralness was assessed by the authors using verbs in the main and subordinate clause with actions that could be performed either by the subject or object antecedent.

The experimental sentences contained two same-gender proper names, one in subject position and one in object position. Half of the sentences contained two male names and the other half contained two female names. Each sentence was manipulated to create four conditions, as illustrated in Table 2. The subject and object antecedents always appeared in the main clause. A null- or an overt-subject pronoun either preceded or followed the antecedents, to create two conditions with anaphoric pronouns, and two conditions with cataphoric pronouns. Notice that gender is not an informative cue here, due to the gender similarity of the two proper names.

Table 2. Example of an experimental sentence

After reading each sentence, participants answered a three-choice comprehension question, where one of the possible answers is the subject antecedent (George), one is the object antecedent (Lewis), and one is an external referent not mentioned in the sentence (Someone else), as shown in (8). Notice that the external referent interpretation is possible in null-subject languages, particularly in the case of cataphoric overt pronouns (e.g., Sorace & Filiaci, Reference Sorace and Filiaci2006). The position of the subject, object, and external referent answers was counterbalanced across items.

The experimental items were divided into four lists and, using a Latin square design, each list contained eight sentences per condition. Sixty-four filler sentences that did not contain a null- or overt-subject pronoun were included. Filler sentences contained a varying number of characters of different gender. Filler sentences consisted of one or two sentences, including conjunctions different than when.

Coding and analysis

The task was designed as a QuestionPro online survey. All Mexican-Spanish speakers took the survey online. Italian-speaking participants took either the online survey or completed a pen-and-paper version of the survey. Participants’ accuracy on the filler sentences was at least 85%, suggesting that all participants were paying attention to the task.

We conducted three separate analyses of the results: (a) one where the dependent variable is the number of subject interpretations (e.g., the pronoun is interpreted as Giorgio/Jorge), (b) one where the dependent variable is the number of object interpretations (e.g., the pronoun is interpreted as Luigi/Luis), and (c) and one where we use the external referent interpretation as dependent variable (e.g., the pronoun is interpreted as Qualcun altro/Alguien más/Someone else).

We used logistic mixed-effects regression modeling (LMER; Jaeger, Reference Jaeger2008) to analyze the number of subject interpretations (coded as 1 and 0), in the glmer function. We included in the model the following factors: language group (Italian vs. Spanish), type of pronoun (null vs. overt), and pronoun position (anaphoric vs. cataphoric). All interactions were allowed. The model included the maximal converging random-effects structure allowed by the design (Barr et al., Reference Barr, Scheepers and Tily2013). We followed up on interactions using planned comparisons with the Bonferroni correction.

Results

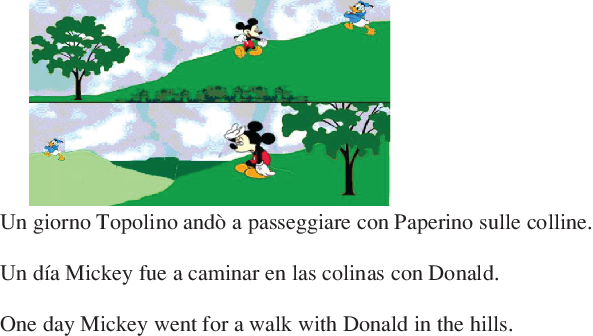

Table 3 summarizes the proportion of subject, object, and external referent interpretations given by the two groups of participants in the four experimental conditions.

Table 3. Proportion of subject, object, and external referent interpretation in Italian and Spanish, by type of pronoun and position of the antecedents (SD)

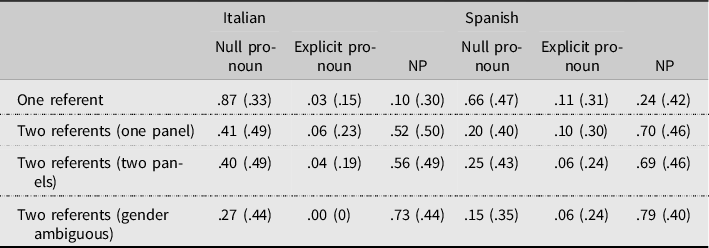

The results of the model where we analyze the subject interpretations as dependent variable are presented in Table 4.

Table 4. Full-model effects (dependent variable: subject interpretations)

Note. The maximal random-effects structure leading to convergence includes by-subject and by-item random intercepts.

The analysis of the subject interpretations revealed significant main effects of type of pronoun and pronoun position. In addition, significant interactions between Language group × Type of pronoun and Language group × Pronoun position emerged. Planned comparisons were conducted to investigate the two interactions. For the Language group × Pronoun position interaction, the planned comparisons showed that, in Italian, speakers chose the subject interpretation more often for cataphoric pronouns (.63) than anaphoric pronouns (.47) (ß = .93, SE = .16, t = 5.70, p < .0004; Intercept: ß = .34, SE = .27, t = 1.26, p = .2), whereas in Spanish this comparison was not significant (anaphora: .49; cataphora: .55). When we compared Spanish and Italian on the subject choices for anaphora (Italian: .47; Spanish: .49) and cataphora (Italian: .63; Spanish: .55), no significant differences emerged between the two languages.

For the Language group × Type of pronoun interaction, the planned comparisons showed that Italian speakers chose the subject interpretation significantly more often for null pronouns (.79) than Spanish speakers (.63) (ß = −1.01, SE = .23, t = −4.24, p < .0004; Intercept: ß =1.26, SE = .20, t= 6.06, p < .0001), whereas no difference emerged for explicit pronouns between the two languages (Italian: .31; Spanish: .42).

In addition, the planned comparisons demonstrated that in both languages participants chose significantly more subject interpretations for null pronouns than for explicit pronouns (Italian: .79 vs. .31: ß = 3.02, SE = .23, t = 12.94, p < .0004; Intercept: ß = .48, SE = .23, t = 1.237, p = .2; Spanish: .63 vs. .42: ß = .98, SE = .15, t = 6.26, p < .0004; Intercept: ß = .13, SE = .16, t = .82, p = .4). The results of the model where we analyze the object interpretations as dependent variable are presented in Table 5.

Table 5. Full-model effects (dependent variable: object interpretations)

Note. The maximal random-effects structure leading to convergence includes by-item random intercepts.

The analysis of the object interpretations revealed significant main effects of Type of pronoun, Language group, and Pronoun position. In addition, significant interactions between Language group × Type of pronoun, Language group × Pronoun position, and Type of pronoun × Pronoun position emerged. Planned comparisons were conducted to investigate the two-way interactions. For the Language group × Pronoun position interaction, the planned comparisons showed that Italian and Spanish did not differ significantly on the number of object interpretations for anaphoric pronouns (Italian: .48; Spanish: .47). However, for cataphoric pronouns, Italian-speaking participants chose the object interpretation significantly more often than Spanish-speaking participants (Italian: .19; Spanish: .08; ß = −2.37, SE = .30, t = −7.74, p < .0004; Intercept: ß = −2.37, SE = .30, t = −7.74, p < .0001).

In addition, the planned comparisons demonstrated that both Italian and Spanish speakers chose more object interpretations for anaphoric than cataphoric pronouns (Italian: .48 vs. .19: ß = −1.81, SE = .31, t = −5.73, p < .0004; Intercept: ß = −.94, SE = .31, t = −3.007, p <. .002; Spanish: .47 vs. .08; ß = −3.64, SE = .63, t = 5.72, p < .0004; Intercept: ß = −1.91, SE = .35, t = −5.33, p < .0001).

For the Language group × Type of pronoun interaction, the planned comparisons showed that Spanish and Italian speakers chose the object interpretation more often for explicit pronouns than for null pronouns (Italian: .54 vs. .13; ß = 2.70, SE = .22, t = −11.95, p < .0004; Intercept: ß = −.99, SE = .33, t = −2.94, p < .003; Spanish: .35 vs. .21; ß = −.76, SE = .16, t = −4.56, p < .0004; Intercept: ß = −1.04, SE = .15, t = −6.85, p < .0001).

When comparing Italian and Spanish, the planned comparisons showed a significant difference in the choice of object interpretations for explicit pronouns in the two languages (Italian: .54; Spanish = .35; ß = −.99, SE = .22, t = −4.33, p < .0004; Intercept: ß = −.09, SE = .15, t = −.63, p = .5), but not for null pronouns (Italian: .13; Spanish = .21; ß = .62, SE = .27, t = 2.23, p = .08; Intercept: ß = −2.07, SE = .27, t = −7.59, p < .0001).

For the Type of pronoun × Pronoun position interaction, the planned comparisons showed that for null pronouns, participants chose the object interpretation significantly more often for null anaphoric pronouns than for null cataphoric pronouns (null anaphora: .26 vs. null cataphora: .06; ß = 2.22, SE = .29, t = 7.65, p < .0004; Intercept: ß = −2.44, SE = .34, t = −7.18, p < .0001) and for explicit anaphoric pronouns compared to explicit cataphoric pronouns (explicit anaphora: .69 vs. explicit cataphora: .24; ß = 2.75, SE = .22, t = −12.15, p < .0004; Intercept: ß = −.26, SE = .24, t = −1.08, p = .2).

The planned comparisons further demonstrated that participants had a preference for the object interpretation for explicit pronouns in comparison to null pronouns, both in the case of anaphora and cataphora (null anaphora: .26 vs. explicit anaphora: .69; ß = −2.17, SE = .19, t = −11.14, p < .0004; Intercept: ß = −.09, SE = .22, t = −.42, p < .6; null cataphora: .06 vs. explicit cataphora: .24; ß = −1.94, SE = .29, t = −6.67, p < .0004; Intercept: ß = −2.88, SE = .37, t = −7.64, p < .0001). The results of the model where we analyze the external referent interpretations as dependent variable are presented in Table 6.

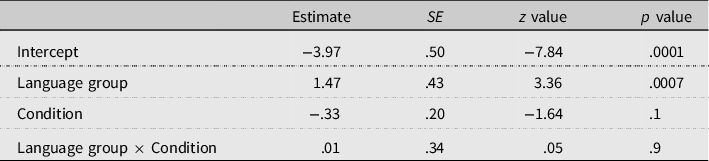

Table 6. Full-model effects (dependent variable: external referent interpretations)

Note. The maximal random-effects structure leading to convergence includes by-item random intercepts.

The analysis of the external referent interpretations revealed a significant main effect of pronoun position and a significant effect of type of pronoun, demonstrating that participants chose the external referent significantly more often for explicit pronouns (.17) than for null pronouns (.09). In addition, a significant interaction between Language group × Pronoun position emerged. Planned comparisons showed a significant difference in external referent choice between anaphoric and cataphoric pronouns in Spanish (anaphora: .02; cataphora: .35; ß = 2.72, SE = .54, t = 5.04, p < .0004; Intercept: ß = −2.35, SE = .26, t = −8.81, p < .0001), but not in Italian (anaphora: .03; cataphora: .16). The planned comparisons also revealed that while Italian and Spanish differed significantly in the choice of external reference for cataphoric pronouns (Italian: .16; Spanish: .35; ß = −.16, SE = .51, t = −.32, p = 1; Intercept: ß = −4.74, SE = .65, t = −7.26, p < .0001), no difference emerged between the two languages for anaphoric pronouns (Italian: .03; Spanish: .02).

Interim discussion

The results of the comprehension study reveal two main results. First, we found a clear division of labor between null and overt pronouns in both languages, as demonstrated by the Language group × Type of pronoun interactions that emerged in the null pronoun and explicit pronoun analyses. This result is in line with previous studies on Italian (Carminati, Reference Carminati2002) and Mexican Spanish (Keating et al., Reference Keating, Jegerski and VanPatten2016), and suggests that the PAH can explain anaphora resolution biases both in Italian and the variety of Mexican Spanish tested here.Footnote 5 Notice that Contemori et al. found a high rate of subject choices in the same variety of Mexican Spanish (38% here vs. 50% in Contemori et al.). This discrepancy is likely because Contemori et al. included in the materials only explicit pronouns and did not counterbalance the stimuli using null pronouns, which may have resulted in adaptation to the higher frequency of explicit pronouns (see Fernandes et al., Reference Fernandes, Luegi, Correa, de la Fuente and Hemforth2018, for similar results on Portuguese).

The second important result for the Language group × Type of pronoun interaction is that two differences emerged between Spanish and Italian: (a) Italian speakers chose the subject interpretation for null pronouns and the object interpretation for overt pronouns significantly more than Spanish speakers and (b) Spanish speakers allowed subject reference with overt pronouns and object reference with null pronouns significantly more than Italian speakers. These effects emerged regardless of the position of the pronouns (anaphoric vs. cataphoric), demonstrating a more flexible interpretation of both pronoun forms in Spanish compared to Italian. This is a new comparative result that is not in line with the study by Filiaci et al. (Reference Filiaci, Sorace and Carreiras2014). Filiaci et al. used a different experimental method (self-paced reading) and materials (anaphoric pronouns in unambiguous sentences; subordinate–main order), testing speakers of a different variety of Spanish. Several of these factors may have contributed to the different results observed and we will come back to this discrepancy in the general discussion.

Concerning the position of the pronoun (anaphoric vs. cataphoric), a Language group × Pronoun position emerged in the three analyses, demonstrating different effects.

In the analysis of the subject interpretations, Italian speakers chose the subject interpretation more often for cataphoric pronouns than anaphoric pronouns, a comparison that was not statistically significant in Spanish. As can be seen in Table 2, this effect in Italian is mainly driven by null pronouns in the cataphoric condition. We explain this result following Carminati’s (Reference Carminati2002) proposal, according to which postmatrix temporal clauses are verb phase (VP) attached. This in turn makes the object a tempting antecedent for the null pronoun in our anaphoric contexts, since it is contained in the currently parsed constituent. Another possible explanation of this result comes from Rizzi’s (Reference Rizzi, Petrosino, Cerrone and van der Hulst2018) proposal that c-command weakens the subject bias of the null pronoun. While in our anaphoric contexts both the subject and the object c-command the null pronoun, this is not the case in our cataphoric contexts.

The results of the Language group × Pronoun position further revealed a stronger preference for interpreting cataphoric pronouns as referring to an external referent in Spanish compared to Italian, and consequently a higher number of object interpretations in Italian than in Spanish. In addition, Italian speakers chose the explicit pronoun for cataphoric pronouns less often than Spanish speakers. While no previous study has analyzed the interpretation of cataphoric pronouns in Spanish, evidence on Italian demonstrated a high choice of external referents for cataphoric pronouns (e.g., Belletti et al. Reference Belletti, Bennati and Sorace2007; Sorace & Filiaci, Reference Sorace and Filiaci2006), a result that we do not replicate here. However, notice that previous studies used a task where pictures depicted subject/object/external referents. It is possible that the task created a more felicitous context for an external referent interpretation than choosing the “someone else” option in the present study. Spanish speakers had a stronger external referent interpretation than Italian speakers, which may reflect the weaker bias that both null and overt pronouns have in Spanish toward interpreting a cataphoric pronoun as rereferring to a subject or an object antecedent, respectively.

Experiment 2: Spoken production

Participants

Two new groups of Italian and Spanish speakers participated in Experiment 2. Thirty-two native speakers of Italian (mean age = 25; SD = 3; range = 20–30; females = 26) were recruited at the Università per Stranieri di Perugia in Italy. Participants were undergraduate and graduate students at the time of testing.

Twenty-six speakers of Mexican Spanish (mean age = 21; SD = 3; range = 19–34; females = 17) were undergraduate students at the Universidad Autónoma de Ciudad Juárez in Mexico.

The Italian speakers reported that they were born in Italy and that Italian was their native and dominant language. As common in European countries, Italian-speaking participants were late learners of a second or third language (English, French, Spanish, German, and Portuguese). Similarly, the Mexican-Spanish speakers were born in Mexico and reported that they were intermediate proficiency late learners of English (see footnote 4).

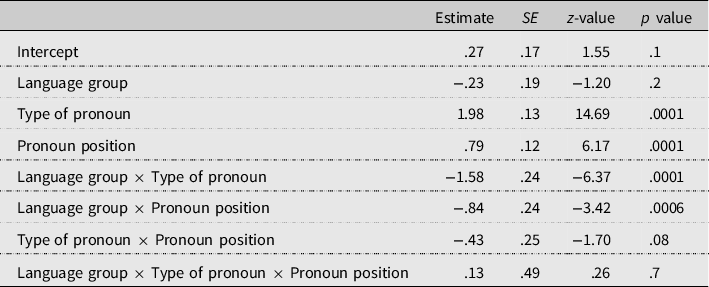

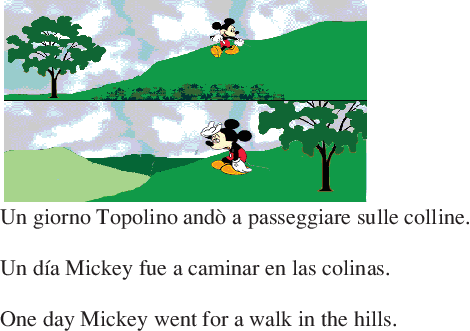

Materials

We adapted a storytelling task used by Arnold and Griffin (Reference Arnold and Griffin2007) to Spanish and Italian. In the task, participants were presented with two-panel pictures. The task consisted of four conditions, where the number, gender, and appearance of the referents in the two pictures were manipulated. In the one-referent condition, only one referent was presented in the two pictures, as shown in Figure 1. In the two-referent conditions, two different gender characters were included in both pictures (Figure 2) or in the second picture only (Figure 3). Finally, one of the two-referent conditions included two similar gender characters that were shown in both pictures (Figure 4). Thirty-two items per condition were counterbalanced across four lists, so that participants were presented only with one version of the same item (a total of four items per condition per list). Sixteen fillers were also included in the task.

Figure 1. One Referent.

Figure 2. Two Referents (in Both Panels).

Figure 3. Two Referents (in One Panel).

Figure 4. Two Referents (Gender Ambiguous).

By testing English speakers, Arnold and Griffin (Reference Arnold and Griffin2007) found a preference for pronoun production in the one-referent condition (Figure 1; e.g., “he was out of shape”) and a preference for full NPs when more than one referent is presented in the preceding discourse (Figures 2, 3, and 4; 2-characters with different gender in both panels; 2-characters with different gender in one panel; 2-characters with same gender in both panels; e.g., “Mickey was out shape”). Arnold and Griffin (Reference Arnold and Griffin2007) found that the production of NPs was modulated by the gender similarity of the two referents, as demonstrated by a higher production of NPs in the condition with same gender characters compared to the conditions with different gender characters. Furthermore, the authors hypothesized that the presence of two referents in the discourse creates competition for attentional resources. As a result, speakers prefer to choose more explicit referring expressions (i.e., NPs) even when a reduced form (i.e., a pronoun) would be felicitous and understandable in the conditions with different gender characters. Furthermore, previous studies have not found an effect of visual presence of the second referent on the choice of referential expressions.

Procedure and coding

The task was designed as a Microsoft PowerPoint presentation. In each item, participants were presented with the first picture and a written description of the picture (e.g., Mickey went for a walk in the hills 1 day). After reading the written sentence aloud, another picture connected to the first one appeared on the slide. Participants were instructed to give a short description of the second picture while pretending that they were telling a story to a 5-year old child.

All Mexican-Spanish speakers completed the storytelling task in person, whereas Italian-speaking participants completed the task as part of a Skype session, due to COVID-19 concerns. Each session was recorded and transcribed. The authors and a research assistant scored the productions. We counted productions in which the participants used either a null pronoun, an explicit pronoun or an NP as a subject to refer to the main character. For the two-referent conditions, we only included in the analysis productions referring to the main character that preceded a mention of the second character. We excluded the following cases from the analysis: productions that contained zero forms with an infinitival clause (e.g., …to exercise on a sunny day…); referring expressions that included more than one character (e.g., they; Minnie and Mickey); naming errors (e.g., Donald for Mickey Mouse); and mentions of the second character, either by itself or before the first character (e.g., …but Donald was walking very fast and Mickey could not keep up). The total amount of productions excluded were 17.5% for Italian (90/512) and 21.1% for Spanish (84/416).

We conducted three separate analyses: (a) one where the dependent variable is the number of null pronouns produced; (b) one where the dependent variable is the number of explicit-subject pronouns produced; and (c) one where we use the NPs produced as dependent variable.

We used LMER (Jaeger, Reference Jaeger2008) to analyze our dependent measures (coded as 1 and 0), in the glmer function. We included in the model the following factors: Language group with two levels (Italian vs. Mexican Spanish) and condition with four levels (one character; two characters with different gender in both panels; two characters with different gender in one panel; and two characters with same gender in both panels). The model included the maximal converging random-effects structure allowed by the design (Barr et al., Reference Barr, Scheepers and Tily2013). Planned comparisons were conducted using the Bonferroni correction.

Predictions

The results of the comprehension study demonstrated that the interpretation biases for null and overt pronouns in Spanish are less strong than in Italian. However, a question that remains to be answered is how flexible is the use of these pronouns in the two languages. A more flexible production pattern in Spanish compared to Italian may explain the weaker Spanish interpretation biases.

We expect that both Italian and Spanish speakers will produce a high number of null pronouns in the one-referent condition, where the preceding subject is highly accessible. Since the task is meant to elicit references to subjects, we predict that overt pronouns will be employed by Italian speakers to a lower extent than Spanish speakers. On the other hand, since Spanish speakers demonstrated more flexible anaphora resolution biases for pronouns than Italian speakers in Experiment 1, we predict that they may produce fewer null-subject pronouns and more overt pronouns than the Italian group to refer to subject antecedents. The effect may emerge in all conditions, demonstrating a more interchangeable use of the two pronouns to refer to a salient antecedent (e.g., the preceding subject) across all contexts.

In the two-referent conditions, we expect that participants will prefer to use NPs to refer to the preceding subject because they experience competition for attentional resources due to the presence of two characters in the preceding discourse (Arnold & Griffin, Reference Arnold and Griffin2007). Since the expected available alternatives are null pronouns vs. full NPs (at least in Italian, as explained above), we do not expect a “gender effect” (i.e., a lesser use of full NPs in the condition with two characters with different gender compared to the condition with two characters and same gender) contrary to what Arnold and Griffin (Reference Arnold and Griffin2007) found for English, since null pronouns do not disambiguate between two different gender referents, if the “gender effect” reflects an ambiguity avoidance strategy.

If instead the gender effect is the result of higher competition in the discourse model when the two referents share the same features (see the discussion in Arnold & Griffin, Reference Arnold and Griffin2007), we should find a higher use of NPs in the condition with two characters of the same gender compared to the condition with two characters and different gender.

Finally, as in Arnold and Griffin, the presence of two characters in the first panel versus on both panels should not modulate participants’ referential choice (two characters with different gender in both panels; two characters with different gender in one panel). Thus, the comparison between the conditions with two characters in one panel and two characters in both panels is not expected to be significant.

Results

Table 7 summarizes the proportion of null pronouns, explicit pronouns and full NPs produced by Italian and Spanish speakers in the four conditions. The results of the model where we analyze the null-subject pronouns as the dependent variable are presented in Table 8.

Table 7. Proportion of null pronouns, explicit pronouns, and full noun phrases (NPs) produced by Italian and Spanish speakers in the four conditions (SD)

Table 8. Full-model effects (dependent variable: null-subject pronouns)

Note. The maximal random-effects structure leading to convergence includes by-subject and by-item random intercepts, with by-item random slopes for the effect of condition.

The analysis of null pronouns revealed a significant main effect of Language group and a significant main effect of condition, and no interaction between the two factors. The main effect of Language group indicates that Italian speakers produced significantly more null pronouns than Spanish speakers (.50 vs. .32). For the main effect of condition, the planned comparisons showed that participants produced more null subjects in the one-character condition (.77) in comparison to (a) the condition with different gender referents in both panels (.33) (ß = −2.2, SE = .30, t = −7.43, p = .0006; Intercept: ß = .43, SE = .22, t = 1.94, p = .05), (b) the condition with different gender referents in one panel (.32) (ß = −2.25, SE = .31, t = −7.16, p = .0006; Intercept: ß = .36, SE = .19, t = .91, p = .05), and (c) the condition with same-gender referents (.21) (ß = −3.01, SE = .39, t = −7.62, p = .0006; Intercept: ß = .03, SE = .21, t = .15, p = .8). No significant difference emerged between the conditions with two characters. The results of the model where we analyze the explicit-subject pronouns as dependent variable are presented in Table 9.

Table 9. Full-model effects (dependent variable: explicit pronouns)

Note. The maximal random-effects structure leading to convergence includes by-subject and by-item random intercepts, with by-item random slopes for the effect of Condition.

The analysis of explicit pronouns revealed a significant main effect of Language group, demonstrating that Spanish speakers produced more explicit pronouns (.08) than Italian speakers (.03). No other main effect or interaction emerged from the analysis.

The results of the model where we analyze the NPs produced as the dependent variable are presented in Table 10.

The analysis of full NPs produced by the two groups revealed significant main effects of language group and condition, and no significant interaction between the two factors.

Table 10. Full-model effects (dependent variable: full NPs)

Note. The maximal random-effects structure leading to convergence includes by-subject and by-item random intercepts, with by-item random slopes for the effect of Condition.

The main effect of language group indicates that Spanish speakers produced significantly more NPs than Italian speakers (.59 vs. .46). For the significant effect of condition, the planned comparisons showed that participants produced fewer NPs in the one-character condition (.16) in comparison to (a) the condition with different gender referents in both panels (.61) (ß = 2.64, SE = .32, t = 8.09, p < .0006; Intercept: ß = −.87, SE = .27, t = −3.13, p < .001), (b) the condition with different gender referents in one panel (.59) (ß = 2.58, SE = .40, t = 6.45, p < .0006; Intercept: ß = −.88, SE = .27, t = −3.18, p <. 001), and (c) the condition with same-gender referents (.76) (ß = 3.16, SE = .33, t = 9.59, p < .0006; Intercept: ß = −.40, SE = .22, t = −1.83, p = .06). A significant difference also emerged between the two conditions with different-gender referents and the same-gender condition (different gender referents in one panel vs. same gender: ß = .84, SE = .28, t = 3.41, p < .01; Intercept: ß = .98, SE = .28, t = 3.41, p < .0006; different gender referents in two panels vs. same gender: ß = .77, SE = .26, t = 2.96, p < .01; Intercept: ß = .97, SE = .24, t = 3.92, p < .0001). No significant difference emerged between the conditions with two different-gender referents.

Interim discussion

The results of the picture description task revealed two main differences between Italian and Spanish. Italian speakers produced significantly more null pronouns than Spanish speakers in all conditions, whereas Spanish speakers produced a higher number of explicit pronouns and full NPs than Italian-speaking participants. Notice that due to the nature of the task, participants’ productions occurred both in contexts of intersentential or intrasentential anaphora, which may limit the comparability of the production and comprehension results. Nonetheless, the production results in Experiment 2 are strikingly similar to the comprehension data. In Italian, speakers prefer to refer to a preceding subject using a null-subject pronoun, while this preference is attenuated in Spanish, a result that we discuss further in the final discussion.

Notice that the administration of the task was different for the two groups of participants (in person for the Spanish group and online for the Italian group). However, the different procedure did not seem to affect our results. During online administration, the experimenter is not physically copresent with the speaker, which may have predisposed the speaker to produce a higher number of NPs, to increase explicitness. On the other hand, when the experimenter is physically present during in-person testing, we may expect that the speaker decreases the number of explicit preferences. However, our results show that the Italian-speaking group tested online produced fewer explicit references (i.e., NPs) than the Spanish-speaking participants tested in person. Thus, we conclude that administration of the task cannot account for the differences observed in production between the two groups.

A second result that we discuss is the differences that emerged between the conditions. The results showed a preference for using null pronouns in the one-referent condition, while no difference emerged between the production of null pronouns in the conditions with two characters. A difference in the use of NPs however did emerge in the same gender versus different gender conditions, with a higher number of NPs in the same gender condition. The lesser use of NPs in the one-character condition for Italian and Spanish confirms what Arnold and Griffin (Reference Arnold and Griffin2007) found for English native speakers. The authors explain this finding assuming that the presence of two characters reduces a referent’s activation (due to competition for attentional resources) and hence a more explicit anaphoric form (i.e., a full NP) is needed when two characters are active in the speaker’s discourse model. Arnold and Griffin (Reference Arnold and Griffin2007) also found a “gender effect”: NPs were more used in the same gender than in the different gender condition, a result that can be interpreted as (a) higher competition in the same gender condition, because the two characters are more similar or (b) ambiguity avoidance. Here, where null pronouns do not disambiguate for gender, we observe a higher use of NPs in the same gender condition than in the different gender condition. This result suggests that competition is higher in the same gender condition than in the different gender condition, due to the increased similarity between the characters.

In Experiment 3, we analyze production biases in Italian and Spanish further, including a comparison of references to object antecedents in contexts of intrasentential anaphora.

Experiment 3: Written production with semantic bias

Participants

Two new groups of Italian and Spanish speakers participated in Experiment 3. Twenty-four native speakers of Italian (mean age = 24; SD = 3; range = 19–31; females = 17) were recruited at the Università per Stranieri di Perugia in Italy. Participants were undergraduate and graduate students at the time of testing.

Twenty-four native speakers of Mexican Spanish (mean age = 25; SD = 5; range = 19–37; females = 12, one participant did not answer the gender question) were undergraduate students at the Universidad Autónoma de Ciudad Juárez in Mexico.

Italian speakers reported that they were born in Italy and that Italian was their native and dominant language. Italian-speaking participants were late learners of a second or third language (English, French, German, Arabic, Spanish, Chinese, and Russian), a common feature in many European countries. Similarly, the Mexican-Spanish speakers were born in Mexico and reported that they were late learners of English at the intermediate proficiency level (see footnote 4).

Material

The production test consisted of a sentence-continuation task that includes implicit causality verbs. Implicit causality is a bias of some interpersonal verbs that denotes semantic causal directionality. The presence of an implicit causality verb in a sentence like (9) is known to influence the interpretation of the pronoun “he.” For example, verbs like frighten and confuse are NP1-biased because they lead to a subject interpretation (e.g., he = John). On the other hand, verbs like love and respect, known as NP2-biased, lead to an object interpretation of the pronoun (e.g., he = Simon).

Previous studies have demonstrated that in a sentence like (9), comprehenders have strong expectations based on the verb’s implicit causality bias with respect to who is going to be mentioned in the subordinate clause. These effects have been observed consistently in reading and listening across different languages, including Italian (e.g., Hartshorne et al., Reference Hartshorne, Sudo and Uruwashi2013; Mannetti & de Grada, Reference Mannetti and de Grada1991) and Spanish (Goikoetxea et al., Reference Goikoetxea, Pascual and Acha2008; Hartshorne et al., Reference Hartshorne, Sudo and Uruwashi2013). While in Experiment 2, we only measured references to subject antecedents; in Experiment 3, we used semantically biased sentences to elicit subject and object pronoun references. In our study with Spanish and Italian participants, we included fragments that contained two NPs in subject/object position, an implicit causality verb (NP1 or NP2-biased) and the causal connective because, as shown in (10) and (11).

Mary respected Paul because

Participants were instructed to complete the sentence with a continuation that sounded natural to them. We expected that participants would continue the sentence with NP1-biased verbs with a reference to the preceding subject/NP1 and that they would continue a sentence with NP2-biased verbs with a reference to the preceding object/NP2, as observed in previous studies (e.g., Hartshorne et al., Reference Hartshorne, Sudo and Uruwashi2013). Here, we are interested in the type of referential expression (null pronoun, overt pronoun, and full NP) that participants choose to refer to the subject/object antecedent. For our sentence-completion task, we selected 24 implicit causality verbs from previous studies (Goikoetxea et al., Reference Goikoetxea, Pascual and Acha2008): 12 with a NP1/subject bias and 12 with a NP2/object bias. Italian implicit causality verbs were translations of the Spanish implicit causality verbs and were carefully matched on frequency. A paired-sample t-test comparing the frequencies of Spanish and Italian verbs measured with the SUBTLEX-IT and the SUBTLEX- ESP databases (Crepaldi et al., Reference Crepaldi, Amenta, Mandera, Keuleers and Brysbaert2013; Cuetos et al., Reference Cuetos, Glez-Nosti, Barbón and Brysbaert2011) did not reveal a significant difference (t(46) = 1.500, p = .1).

In the sentence-continuation task, the sentences included stereotypical male and female names that were counterbalanced across subject and object positions in the sentences. The reason to use female and male names is that we expected the participants to often omit the NP in subject position in the subordinate clause introduced by because. Therefore, the use of two NPs that differ in gender in the lead-in sentence allowed a clearer identification of the intended subject in the because clause. As shown in (10) and (11), the subject NP was followed by the implicit causality verb and the object NP.

Twenty-four experimental sentences (12 with NP1/subject biased verbs and 12 with NP2/object-biased verbs) were interspersed with 48 fillers that had similar structure as the experimental items, but that did not contain any implicit causality verb. One list was constructed, and then a second list resulted from putting the items in the opposite order. Participants were given either a pen-and-paper version of the sentence-continuation task, or an online version constructed as a QuestionPro survey.

Coding

For the Spanish sentence-completion task, one of the authors and a native Spanish speaker unaware of the purpose of the study scored the productions as subject or object continuations. For the Italian sentence-completion task, the first and second authors scored the productions as subject or object continuations. The scoring was then compared until 100% agreement was reached after discussion. A subject continuation was scored as such if the continuation unambiguously referred to the first mentioned entity in the preceding discourse (e.g., Laura asombró a Jesús porque ella nunca le grita; Laura surprised Jesus because she never yells at him), whereas an object continuation required that the null/explicit pronoun referred to the second mentioned entity in the preceding discourse (e.g., María respetó a Pablo porque él es muy educado; Maria respected Pablo because he is very polite). Responses were coded as “unclear” if the referent for the pronoun remained unclear. A total of 13/576 responses and 40/576 responses were labeled unclear for Italian and Spanish, respectively. An additional 13/576 responses in the Italian dataset and 32/576 in the Spanish dataset were discarded because they contained a subject other than the first or the second referent (e.g., they, nobody, Maria, and Pablo).

After the subject/object continuation labeling, the responses were categorized according to the type of subject used in the completion. Three categories were used: null pronoun, explicit pronoun, and full NP. In the statistical analyses, we analyzed the number of null- and explicit-subject pronouns using language group (Spanish vs. Italian) and verb bias condition (NP1/subject biased vs. NP2/object biased) as main factors. Full NPs were scarcely produced and therefore were not analyzed as dependent variable. We used mixed-effects logistic regression and simplified the random-effects structure until convergence was reached (Barr et al., Reference Barr, Scheepers and Tily2013). We used a stepwise backward inclusion procedure and tested both first-level effects and the interactions between the fixed-effect factors. The completions per each subject and item was coded as 1 or 0 and analyzed using glmer (lme4 library, Bates & Sarkar, Reference Bates and Sarkar2007). Planned comparisons were conducted to investigate interactions using the Bonferroni correction.

We included in the analysis only responses that were congruent with the bias of the verb. For NP1/subject bias verbs, noncongruent responses amounted to 57/288 in Spanish (19%) and 49/288 (17%) in Italian. For NP2/object-biased verbs, noncongruent responses amounted to 75/288 in Spanish (26%) and 72/288 (25%) in Italian. A statistical analysis that included all participants’ responses regardless of bias congruency was performed, including subject reference and object reference as a main factor. The results were identical to the results of the statistical analysis reported here where the bias incongruent responses were discarded.

Predictions

The picture description task in Experiment 2 tested reference to preceding subjects in sentences that were not controlled for intrasentential versus intersentential position. In Experiment 3, the implicit causality manipulation allows to test null/overt pronouns produced to refer to both subject and object antecedents. In addition, the implicit bias manipulation allows to analyze referential choice within the same sentence (intrasentential position).

In a previous study on Peninsular Spanish using the implicit causality manipulation, a high percentage of null pronouns was found using a sentence completion task similar to ours (Goikoetxea et al., unpublished, reported by Hartshorne et al., Reference Hartshorne, Sudo and Uruwashi2013). In fact, in these highly biased semantic contexts, we expect that both Italian and Spanish speakers prefer to produce the default referential form, that is, the null pronoun.

For references to the object antecedent, we predict that participants will be more likely to use overt pronouns to refer to object referents than to subject referents, a preference that we observed in the comprehension task (Experiment 1). In addition, it is possible that the semantic bias makes the object antecedent highly predictable. Thus, consistently with Calabrese (Reference Calabrese, Fukui, Rapoport and Sagey1986)’s assumptions, null pronouns may be produced to refer to both the subject and object antecedents to a high extent.

Finally, in line with Experiment 2, we expect to find a higher production of null pronouns in Italian than in Spanish, and a higher production of overt pronouns in Spanish compared to Italian. This result would confirm the observed pattern in the variety of Spanish tested here, that is, that the use of null and overt pronouns is more flexible than in Italian.

Results

Table 11 summarizes the proportion of null pronouns, explicit pronouns, and full NPs produced by Italian and Spanish speakers in the NP1 and NP2 verb bias condition. The results of the model where we analyze null-subject pronouns as dependent variable are presented in Table 12.

Table 11. Proportion of null pronouns, explicit pronouns, and full NPs produced by Italian and Spanish speakers in the two conditions (SD)

Table 12. Full-model effects (dependent variable: null-subject pronouns)

Note. The maximal random-effects structure leading to convergence includes by-subject and by-item random intercepts, with by-item random slopes for the effect of condition.

The analysis of null pronouns as dependent variable revealed a significant main effect of language group, indicating that Italian speakers produced more null-subject pronouns (.92) than Spanish speakers (.85). A main effect of verb bias condition also emerged, demonstrating that participants produced significantly more null pronouns in reference to the preceding subject (NP1 verb bias: .95) in comparison to the preceding object referent (NP2 verb bias: .79)

The results of the model where we analyze the explicit-subject pronouns as dependent variable are presented in Table 13.

Table 13. Full-model effects (dependent variable: explicit-subject pronouns)

Note. The maximal random-effects structure leading to convergence includes by-subject and by-item random intercepts, with by-item random slopes for the effect of condition.

The analysis of explicit pronouns as dependent variable revealed a significant main effect of language group, indicating that Italian speakers produced significantly fewer explicit-subject pronouns (.07) than Spanish speakers (.14). A main effect of verb bias condition also emerged, demonstrating that participants produced significantly fewer explicit pronouns in reference to the preceding subject (NP1 verb bias: .04) in comparison to the preceding object referent (NP2 verb bias: .20).

Finally, an interaction between language group and verb bias condition approached significance. Although the interaction is not fully significant, we conducted planned comparison to further understand the nature of the effect. The planned comparisons showed that both Spanish and Italian speakers produced more explicit pronouns in reference to object than subject referents (Italian: ß = 4.87, SE = 1.23, t = 3.94, p < .0004; Intercept: ß = −6.80, SE = 1.84, t = −3.69, p < .0002; Spanish: ß = 1.60, SE = .26, t = 6.01, p < .0004; Intercept: ß = −1.96, SE = .13, t = −14.12, p < .0001).

When we compared Spanish and Italian, the planned comparisons showed a significant difference between the explicit pronouns produced for object referents between the two languages (ß = 2.57, SE = 1.03, t = 2.48, p < .04; Intercept: ß = −5.85, SE = 1.08, t = −5.42, p < .0001) and no significant difference for explicit pronouns produced in reference to subject antecedents.

Interim discussion

In Experiment 3, we measured the references produced to subject and object antecedents in semantically biased contexts. The analysis of the null pronouns revealed that both groups of participants were sensitive to the implicit causality manipulation, producing significantly more null pronouns in reference to the preceding subject than in reference to the preceding object. In addition, Italian-speaking participants produced more null pronouns than Spanish speakers, to refer to both antecedents. This result is in line with the data presented in Experiment 2. In addition, it indicates that the null subject is the default pronoun adopted in Italian when there is no ambiguity in interpretation, whereas its use is somewhat more limited in Spanish.

The main effect of verb bias showed that, as predicted, participants produced significantly fewer explicit pronouns in reference to the subject than the object referent. Notice that an interaction between Language group × Verb bias condition approached significance, suggesting that Spanish speakers produced more explicit pronouns for object referents than Italian speakers. While this effect should be taken cautiously because it is not fully significant, it may indicate a qualitative difference in the use of explicit pronouns in the two languages. Future studies should investigate production in implicit causality contexts in Spanish to fully understand the nature of this effect.

Overall, Experiment 2 showed that explicit pronouns can be produced to a higher extent in Spanish in reference to subject antecedents than in Italian, regardless of the number of referents in the context. In Experiment 3, the results seem to indicate that while explicit pronouns are used in the two languages significantly more to refer to object than subject antecedents, the use of null subjects is overall very high. We explain this result proposing that NP2-biased verbs make the object an expected referent: hence, Italian speakers (more than Spanish speakers) use a null pronoun to refer to it, consistently with Calabrese (Reference Calabrese, Fukui, Rapoport and Sagey1986)’s predictions.

Final discussion and conclusions

In the present study, we conducted three experiments looking at the comprehension and production of null and explicit pronouns in Spanish and Italian. Our first question is understanding if the PAH can account for the comprehension pattern observed in Italian and in the variety of Mexican Spanish under investigation. The results of the comprehension study revealed a clear asymmetry in the interpretation of null and explicit pronouns in Italian and Spanish, with a preference to interpret a null pronoun as referring to the preceding subject and a preference to interpret explicit pronouns as referring to object antecedents. While individual variability across speakers may exists, the results of the comprehension study clearly demonstrate that the PAH can explain anaphora resolution in the two languages. The results on Italian confirm previous studies by Carminati (Reference Carminati2002) and Filiaci et al. (Reference Filiaci, Sorace and Carreiras2014), whereas the results from Spanish are in line with previous studies on Mexican Spanish and Spanish spoken by Spanish–Catalan bilinguals (Bel and García-Alcaraz, Reference Bel, García-Alcaraz, Judy and Perpiñán2015; Bel et al., Reference Bel, Sagarra, Comínguez and García-Alcaraz2016; Keating et al., Reference Keating, Jegerski and VanPatten2016).

Concerning our second question about the comparability of the comprehension patterns in Italian and Spanish, the results demonstrate that the two languages exhibit a different division of labor for null- and overt-subject pronouns. More specifically, while the interpretation biases for null and overt pronouns are very distinct in Italian, the preferences are less strong in Spanish. This comparative result is not in line with previous research by Filiaci et al. (Reference Filiaci, Sorace and Carreiras2014), where Peninsular-Spanish speakers did not show a clear preference for the interpretation of explicit pronouns. As it clearly emerges in our results, while the null-subject pronoun is the default referential form in Italian, no strong default bias emerges in Spanish. This result differs from Filiaci et al. (Reference Filiaci, Sorace and Carreiras2014), where the authors did not find any differences between Italian and Spanish on the interpretation of null pronouns.Footnote 6 Future research should focus on a qualitative analysis of different discourse contexts in Spanish comprehension and production to further explore the nuances of the use of null and explicit pronouns.

A limitation of the present study is that we looked only at northern Mexican Spanish and we do not know if our results can be generalized to other varieties of (Mexican) Spanish. Nonetheless, we speculate that an attenuated division of labor in Spanish may explain why existing evidence on anaphora resolution in this language is so mixed. If the difference in interpretation of null and overt pronouns is not so robust in Spanish, these effects may be more elusive and emerge more inconsistently across different studies. For example, small differences in the sentence structure and meaning (e.g., semantic cues, connectors, and ambiguity of the sentence) or a mix of participants’ language varieties (e.g., Filiaci et al., Reference Filiaci, Sorace and Carreiras2014) could change patterns of interpretations more radically if null- and overt-pronoun preferences are not as clear-cut.

As to why pronoun use and interpretation differ in closely related languages like Spanish and Italian, we suggest, along the lines of Di Domenico and Matteini (Reference Di Domenico and Matteini2021), that it is not uncommon that a property made available by the grammar may be employed differently by languages sharing this same property. One example is the availability of the postverbal subject position (a property shared by all null-subject languages), which in Italian, but not in Greek encodes a new information focus feature (e.g., Belletti, Reference Belletti, Hulk and Pollock2001, Reference Belletti and Rizzi2004; Roussou and Tsimpli, Reference Roussou and Tsimpli2006). Similarly, we may expect that the availability of two different subject pronouns may be implemented differently in Italian and Spanish. Furthermore, recent comparative studies looking at other null-subject language pairs have shown microdifferences in subject realization and interpretation (e.g., Spanish–Greek: Giannakou & Sitaridou, Reference Giannakou and Sitaridou2020; Greek–Italian:Di Domenico et al., Reference Di Domenico, Baroncini and Capotorti2020; Torregrossa et al., Reference Torregrossa, Andreou and Bongartz2020). While some research has linked microdifferences in subject realization to other properties of the languages investigated (e.g., Filiaci et al., Reference Filiaci, Sorace and Carreiras2014; Giannakou & Sitaridou, Reference Giannakou and Sitaridou2020; Leonetti Escandell et al., Reference Leonetti Escandell, Torregrossa and Andreou2019), our study cannot provide conclusive evidence to address this question. Thus, we leave this topic open to future research.

The third research question that we aimed to address is how pronoun production compares to anaphora resolution patterns in comprehension. To our knowledge, our study is the first comparative research that includes an investigation of production and comprehension in Italian and Spanish, showing that the two modalities are closely linked in the two languages. Spanish speakers use null pronouns to a lesser extent than Italian speakers to refer to a preceding subject, and use a higher number of explicit pronouns and NPs (Experiment 2). As for reference to object antecedents, the results of Experiment 3 demonstrate that the verb’s implicit causality, in the relevant cases, makes the object referent an expected (and highly predictable) antecedent. In this case, Italian speakers employ a null pronoun to corefer with the object more than Spanish speakers. Future research should examine how reference to an unexpected object antecedent is realized, to clarify if any differences are confirmed between the two languages and to further investigate how the expectancy of the referent affects pronoun choice (e.g., Calabrese, Reference Calabrese, Fukui, Rapoport and Sagey1986). In addition, references to the object should be investigated using a different methology than the one used in Experiment 3, to include neutral sentences comparable to the ones used in the comprehension study.

The present study contributes to our understanding of the relation between comprehension and production at the discourse level, suggesting that subtle differences in pronoun use pattern with interpretation biases. This result is in line with different assumptions about the relation between comprehension and production of pronouns. On the one hand, probabilistic models of reference suggest that production patterns determine interpretation preferences and that comprehenders rely on calculations of probabilities about the likelihood of subject and object referents to be rementioned based on frequent discourse patterns (e.g., Arnold, Reference Arnold2016, for a review). Alternatively, if discourse-related features are represented in the grammar, a similarity between interpretation and production patterns is also predicted. For example, as suggested by Cardinaletti and Starke (Reference Cardinaletti, Starke and van Riemsdijk1999), antecedent’s retrieval properties are coded in the pronoun itself together with syntactic, semantic, morphological, and phonological properties. Under this account, the grammar drives interpretation and production, determining a similarity between comprehension and production patterns. Finally, our results are also compatible with the asymmetric grammar approach (Koster et al., Reference Koster, Hoeks, Hendriks, Grimm, Müller, Hamann and Ruigendijk2011). Under this account, the grammar consists of direction-sensitive constraints that are potentially conflicting between comprehension and production. However, the conflicting contraints do not create asymmetries between production and comprehension because adults can take into account the listener’s perspective.

To conclude, our study shows that microvariation may be expected on pronoun comprehension across languages with similar syntactic properties. However, taking into account the production patterns is crucial to pin down the degree of similarity/difference across languages and varieties of the same language. Furthermore, our research demonstrates the importance to test production patterns in future research when investigating anaphora resolution in languages like Spanish where many geographical varieties exist (Carvalho et al., Reference Carvalho, Orozco and Shin2015) and when making comparisons across languages (e.g., Filiaci et al., Reference Filiaci, Sorace and Carreiras2014).

Acknowledgements

We thank Jennifer Arnold and Zenzi Griffin for making their experimental materials available to us. We thank Alma L. Armendariz Galaviz and Diletta Comunello for recruiting participants, collecting, and coding data. Thanks also to three anonymous reviewers and to the audience of the 34th CUNY Conference on Human Sentence Processing and the audience of the 46° Incontro di Grammatica Generativa for helpful comments.