In a recent document related to the EU Trust Fund for Africa, the European Commission stated that “the distribution of the migrant population on Moroccan territory is in evolution. In 2013, the estimated migrant population in Morocco ranged between 20,000 and 40,000 people” (European Commission, n.d.c, 2, translation by author). This sentence, however, contained an evident lapse: “20,000 – 40,000 people” is the figure most currently cited in governmental and non-governmental reports estimating the number of irregular migrants present in Morocco (see, for example, Médecins du Monde and Caritas 2016) – often more explicitly qualified as ‘irregular sub-Saharan’ in both written texts and in oral common use (see, for example, Reference Karibi, Khrouz and LanzaKaribi 2015). In this document, however, the Commission used this figure to refer to the total number of migrants residing in the country. In other words, the report equated the condition of foreigners in Morocco with the condition of irregularity, and implicitly, blackness.

‘Migrant’ and ‘migration’ have become, by and large, racialised words in Morocco. Despite the diversity of immigrant communities that Morocco has historically hosted, a new narrative is gaining ground which recognises the country as an ‘Immigration Nation’ only in reference to the allegedly ‘new’ population of ‘black’, ‘transit’, ‘irregular’ migrants allegedly proceeding from West and Central Africa towards Europe. This description, however, is deceptive. Immigration in Morocco is neither novel, nor exclusively or predominantly involving black people from other parts of Africa. Morocco has hosted immigrant communities well before the signature of the Schengen Agreement, to such an extent that the official number of foreign residents captured by Moroccan records was seven times higher in 1952, at the time of the Protectorate, than in the 2014 census. European migrants have always formed an important foreign presence in Morocco, which outnumbers that of Africans in the official census. Although it is true that censuses do not capture irregular migration, this logic works both ways: if it is difficult to estimate how many irregular West and Central Africans are not counted by official records, the same thing can be said for irregular Europeans and North Americans.

This chapter examines the role that the migration industry plays in the political production of Morocco as an ‘Immigration Nation’. I argue that aid agencies stage discourses and practices that normalise an understanding of immigration in Morocco as a predominantly ‘black’, ‘transit’, ‘irregular’ experience. This historically selective image of migration ignores the multifaceted dynamics of incoming mobility in Morocco, and it tallies with the concerns of European donors over a potential ‘African invasion’ (de Reference HaasHaas 2008). By creating, socialising, and reproducing such a biased representation of immigration in Morocco, aid agencies produce what Foucault calls a “regime of truth,” a system of implicit rules and ideologies that produce certain statements and facts as obviously true or even common sense (Reference FoucaultFoucault 1980, 132).

Although thinking of Morocco as a recent country of immigration has become mainstream discourse, this image is not a foregone conclusion obtained through an objective reading of Moroccan migration history. A regime of truth does not simply exist. It needs to be produced, socialised, and learnt, so that it can become hegemonic over alternative forms of knowledge (Reference Berger and LuckmannBerger and Luckmann 1979). The capacity to influence and shape the constitution of a specific regime of truth is uneven, as is the distribution of power within society. Actors with the capacity to concentrate “physical force,” “economic,” “informational” and, more importantly, “symbolic” power have more leverage in the creation and reproduction of reality (Reference BourdieuBourdieu 1994, 13; see also Reference CroninCronin 1996). In countries on the receiving end of externalisation policies, development and humanitarian organisations have such capacity. They produce leaflets, presentations, and factsheets about immigration in Morocco, thus localising resources that transform migration into a visible theme of intervention. During an interview, Daniele, an Italian development consultant, invited me to think differently about how donors managed to push their political agenda in an aid-recipient context like Morocco. “The EU does not impose,” he told me, “but the EU has more weight, and therefore its political vision matters more than the political vision of another country, but it is not a constant will to impose [its political vision], in my opinion.”Footnote 1

The rest of the chapter falls into three sections. First, I retrace the history of immigration in Morocco, highlighting both its multidirectionality and its intimate connection with broader histories of empire. In so doing, I propose an alternative “regime of truth” against which to read the intervention of the migration industry. By casting attention on the multifaceted, longer histories of mobility in the country, I de-exceptionalise the significance of ‘sub-Saharan transit migration’ within the broader migratory landscape characterising Sahelian and Mediterranean Africa. The following two sections unravel the discourses and practices through which Morocco is produced as an ‘Immigration Nation’. I contend that donors, NGOs, and IOs entrench ideas about binary categories of migrant ‘transit’ and ‘settlement’ onto the ground. They do it not only by promoting specific narratives about migration, but also by spatialising aid projects through migration routes and by adapting project activities to the boundaries of permissibility allowed by Moroccan authorities.

An Overview of Immigration in Morocco

Stating that Morocco is a recent country of immigration elides the role that the Alaouite Kingdom has historically played in the political economy of military, commercial, and touristic exchanges in the Maghreb, and in the Mediterranean more broadly. Foreigners from West and Central Africa were a steady presence in Morocco well before the twenty-first century. Especially after the Arab conquest, the Maghrib and Sahelian Africa were connected by caravan trade. Through the trans-Saharan route, goods, precious materials, and captives were transported from the Bilad al-Sudan to North Africa. As Morocco was well connected in the trans-Saharan slave trade, the presence of enslaved populations in the country was recorded from as early as the ninth century (Reference EnnajiEnnaji 1999). Although estimating how many black Africans arrived in Morocco as captives through the slave trade is challenging, Wright reports that in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries the figure ranged between 2,500 and 4,000 slaves per year (Reference WrightWright 2007). The institution of slavery was never officially abolished as such, its practice continued until the twentieth century, and its memory is still deeply inscribed in the minds and rituals of slave descendants (Reference BeckerBecker 2002). However, a series of reforms introduced in the latest stage of the Sherifian Empire (Reference EnnajiEnnaji 1999) and then during the Protectorate practically led to its slow disappearance (Reference El HamelEl Hamel 2012). The trans-Saharan slave trade obviously did not exhaust the network of exchanges connecting West and Central Africa to Morocco. Morocco was a destination for religious pilgrims, especially from Senegal, heading to the mausoleum of Ahmed al-Tijani, founder of the Tijaniyya brotherhood in Fes (Reference Berriane, Aderghal, Janati and BerrianeBerriane et al. 2013; Reference LanzaLanza 2014). From the start of the twentieth century until the late 1980s, Casablanca was a procurement hub for small Senegalese traders who bought merchandise which they would later resell back home (Reference PianPian 2005). Since the 1970s, the diplomatic cooperation of Morocco with West and Central African countries has transformed Moroccan universities into a pole of attraction for students and a centre of formation for future African bureaucrats (Reference BerrianeBerriane 2015; Reference Infantino and PeraldiInfantino 2011).

Labelling Morocco as a country of immigration more subtly (and strikingly) elides the history of European migration to North Africa, and its intimate connection to the onset and expansion of French and Spanish colonialism. The presence of European migrants in the country was scarce until the end of the eighteenth century. However, the decision of Sultan Sidi Mohammed Ben Abdellah to open the empire to the world paved the way for the emergence of European communities, particularly in Tangier (Reference López García, Aouad and BenlabbahLópez García 2008), reconverted in 1856 into Morocco’s diplomatic capital (Reference TherrienTherrien 2002). For most of the nineteenth century, North–South migration flows remained limited in scope and spontaneous in nature. At the turn of the century, however, the increasing political and economic influence exercised by European powers over Morocco increased the presence of European migrants and tourists in Moroccan urban centres (Reference PackPack 2019). Tangier is a chief example of this phenomenon: by far the most cosmopolitan Moroccan city at the time, in 1909, it counted 9,000 European residents over a total population of 45,000 people (Reference López García, Aouad and BenlabbahLópez García 2008). Although Morocco was never a settler colony like neighbouring Algeria, the formal establishment of the Protectorate in 1912 accelerated the flow of people from Europe to French and Spanish-controlled areas, and to Tangier, placed under international rule in 1923: soldiers, colonial bureaucrats, and travel writers, but also people of modest means – shopkeepers, artisans, construction workers, day labourers, all leaving the metropole to find fortune in the colony (Reference PackPack 2019). As the number of European residents in Morocco doubled from 44,576 people in 1913 to 98,191 in 1920, the urban architecture of Moroccan cities started acquiring a distinct European trait (Reference López García, Reyes, Jurado and BenlabbahLópez García 2013). This was not only the result of the establishment of cafés, hotels, and entertainment venues founded or run by Europeans and with European-sounding names, like the Gran Teatro Cervantes in Tangier (Reference López GarcíaLópez García 2014) or the Café de France in Marrakech (Peraldi 2018). In the areas under French rule in particular, the colonial administration promoted deliberate politics of infrastructural reform determined to separate the locals, residing in the medina (the old city), from French colonisers and Europeans more broadly, residing in the ville nouvelle (the newly built quarters) (Reference Radoine and DemissieRadoine 2012; Reference Wagner and MincaWagner and Minca 2014) (see Figure 4). But Morocco did not only host military and civilians making a living out of the colonial venture: during the years of the Spanish Civil War (1936–39), Tangier and the areas under French control became a safety hub for Spanish refugees, mainly republicans escaping conflict first and the dictatorship of Franco later (Reference López García, Aouad and BenlabbahLópez García 2008). After the independence of Morocco in 1956, the presence of European residents substantially decreased, but never fully disappeared (Reference Escher, Petermann, Janoschka and HaasEscher and Petermann 2013; Reference MounaMouna 2016; Reference Therrien and PellegriniTherrien and Pellegrini 2015).

Empire, and its legacy, did not only encourage the immigration of Europeans in Morocco, but distinctively shaped the magnitude and direction of Moroccan emigration. Although Moroccans have emigrated since pre-colonial times, the establishment of colonialism in North Africa significantly boosted international emigration from the country. Moroccan workers and soldiers were moved across the Spanish and French colonial empires, both directly – for example, through the recruitment of Riffian soldiers to fight in the Spanish Civil War in Franco’s troops (Reference MadariagaMadariaga 2002) – and indirectly – as poor Moroccans moved to neighbouring Algeria to seek employment in French colonial farms (de Reference HaasHaas 2003, Reference Haas2005; Reference PackPack 2019)Footnote 2. Even after Moroccan independence, European neo-colonial influence continued bearing significant weight in steering the direction of emigration flows. In the early 1960s, Western European countries started actively recruiting North African and Middle Eastern workers to support the post-war reconstruction effort and the economic boom that had followed. The number of Moroccans emigrating to France, Belgium, and the Netherlands skyrocketed in the 1960s and 1970s, and continued increasing afterwards (de Reference HaasHaas 2005). Despite the tightening of European borders since the 1970s, Moroccans have continued migrating to Europe either through family reunification schemes or through irregular channels (Reference ArabArab 2009; Reference ChattouChattou 1998).

Describing Morocco as a recent country of immigration for ‘sub-Saharan migrants’ seems to give disproportionate attention to one specific form of mobility characterising contemporary North Africa (Reference PeraldiPeraldi 2011). From the 1960s onwards, an intense migration corridor emerged between Sahelian Africa and Libya. The labour shortages created by the Libyan oil boom attracted workers from Arab countries, and to a lesser extent, from Sahelian Africa. These movements gave renewed vitality to trans-Saharan routes (Reference Bredeloup and PliezBredeloup and Pliez 2005; Reference PliezPliez 2006). In the 1990s, the movement of people along these corridors increased. This evolution did not emerge from a social and political vacuum, nor was it driven solely by migrants’ aspiration to reach the European ‘El Dorado’. On the one hand, the disastrous effects of Structural Adjustment Plans rendered the already fragile social and economic conditions of many African countries even more precarious. Many people therefore decided to seek alternative livelihood strategies outside their own communities and countries (Reference Bredeloup and PliezBredeloup and Pliez 2005). On the other hand, the African diplomacy pursued by Ghaddafi in the 1990s transformed Libya into a pole of attraction for workers from Sahelian Africa. The increase of trans-Saharan mobility was simultaneous to the closure of European borders. European policymakers thus began to see North Africa as a place from where Moroccan, West, and Central African nationals would cross irregularly to reach European shores (de Reference HaasHaas 2008).

In public discourse, the presence of West and Central African migrant people in Morocco has always tended to be qualified as ‘transit migration’, as if to imply that migrants were temporarily present on the territory of the state while heading to Europe (Reference DüvellDüvell 2006). After the announcement of the new migration policy in 2013, policymakers and civil society organisations have increasingly marked a discoursive separation between ‘transit migrants’ and ‘settled migrants’, the latter expression being used to refer mainly to people who have been regularised and who have decided to integrate in Morocco (see, for example, Reference Mourji, Ferrié, Radi and AliouaMourji et al. 2016). Both ‘transit’ and ‘settlement’, however, are fictitious terms because they convey the biased message that patterns of mobility can be mutually exclusive. As for ‘transit migration’, migrants do not necessarily plan rationally and a priori to move from A to B passing through C (Reference BacheletBachelet 2016; Reference DüvellDüvell 2006).Footnote 3 Although less theorised, ‘settlement’ is also a category fraught with prejudice, as there is no clear, or a priori, distinction between migrants who want to stay and those who want to leave. People granted refugee status might still hope to be relocated abroad (see Chapter 5). Others, despite living in areas close to the borders, might decide to remain on a longer-term basis in Morocco and regularise their position after being offered a new employment opportunity (see Reference Abena Banyomo and TherrienAbena Banyomo 2019).Footnote 4 Even people signing up for the IOM’s voluntary return programme may envisage coming back to Morocco, and see the return as a transitory stage, as a way to move back home to fix family affairs or to accumulate resources (Reference BacheletBachelet 2016).

In any case, dynamics of transit and settlement of West and Central African migrants constitute but two of the forms of immigration that characterise contemporary Morocco. Although the number of Europeans residing in the country has considerably decreased since the Protectorate, European migrants still populate Moroccan cities (Reference BoudarssaBoudarssa 2017; Reference LachaudLachaud 2014). The key role played by tourism in the country’s economic development plan, and the boom of the low-cost flight industry in the past two decades, has determined an exponential growth in the number of European visitors to the country. In 2019, Morocco recorded the arrival of 7 million foreign tourists – of these, almost 2 million were French, 880,000 were Spanish, and a further 1.8 million came from the United Kingdom, Germany, Italy, Belgium, and the Netherlands (Ministère du Tourisme, de l’Artisanat, du Transport Aérien et de l’Economie Sociale, n.d.). Posters portraying colonial Rabat, Tangier, or Fes form part of the stock of memorabilia invariably present in shops catering to European tourists in Morocco’s urban centres, durably written in a marketing strategy selling “colonial nostalgia” to the tourist masses (Reference Minca, Borghi, Obrador Pons, Crang and TravlouMinca and Borghi 2009).

But Europeans are not only tourists in Morocco: as much as they might perceive their presence as transient, thousands of migrants from the Global North move to Morocco for lengthier periods of time for a variety of reasons, including for family, a desire of “elsewhereness” (Reference Therrien and PellegriniTherrien and Pellegrini 2015), a better lifestyle in a country where the cost of living is cheaper and the weather is sunnier, or for work. Europeans who have moved to Morocco for employment reasons include those who were offered a better job opportunity than in their home countries, and those whose company delocalised production to Morocco. It also includes people who moved in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, and who engage in relatively precarious jobs for a living (Reference MounaMouna 2016; Reference Peraldi and TerrazzoniPeraldi and Terrazzoni 2016). During my fieldwork, my own whiteness faded in the background of upper-class neighbourhoods of major Moroccan cities. But when I stepped into lower-income neighbourhoods, my presence went much less unnoticed. “Le noir, c’est ton mari?” (The black man, is he your husband?) asked the driver of a collective taxi that I had hopped into after meeting with a Cameroonian friend for a coffee in a migrant-populated neighbourhood of Rabat.Footnote 5 “Sbaniula?” (Are you Spanish?) an older Moroccan man asked me, while sitting in a café in a low-income neighbourhood of Tangier, nodding towards the community centre across the street. I knew why he thought I was Spanish. The community centre he was pointing to had been built with Spanish aid money two decades before and was peopled by Spanish aid workers for most of that time. My whiteness led people to think that I, too, might have been a European aid worker (see Reference GazzottiGazzotti 2021).Footnote 6

Although Europeans receive considerably less media and political attention than people racialised as ‘sub-Saharans’, they are not exempted from the irregular practices of mobility. It is well known, in fact, that many European citizens live and work in the country as tourists, taking advantage of a legislative gap in the Moroccan immigration act which allows them to enter and exit the country every ninety days to renew the stamp on their passport (Reference KhrouzKhrouz 2016a; Reference Zeghbib, Therrien and TherrienZeghbib and Therrien 2016). It is also documented that European and North American citizens play with the boundaries of migration law, overstaying the ninety days allowed by law or working as a tourist without encountering much trouble with Moroccan authorities (Reference GazzottiGazzotti 2021).

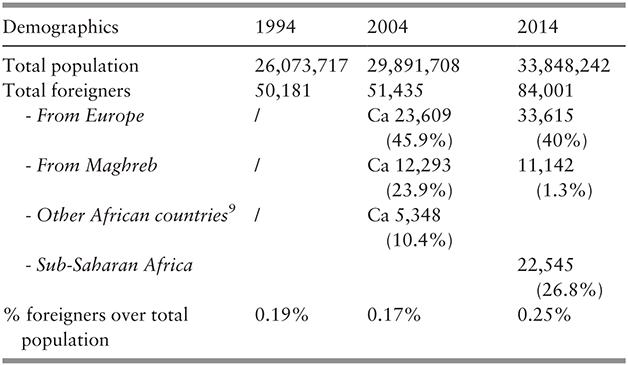

Both South–North and North–South migration carry weight in the composition of the Moroccan immigration landscape (see Table 1). In 2014, foreign residents represented approximately 0.25 per cent of the total Moroccan population. Out of 84,001 foreign residents, 22,545 were from another African, non-Maghreb country, while 33,615 were Europeans (Haut Commissariat au Plan 2017c). These data should technically include undocumented foreigners, but are generally considered to either exclude or to severely underestimate them.Footnote 7 Estimates of undocumented migration vary, ranging between 10,000–30,000 (European Commission 2016) and 25,000–40,000 (Moroccan Ministry of Interior, in Médecins du Monde and Caritas 2016). Despite being commonly used by most aid agencies, it is not clear how these figures about irregular migration are produced, whether they incorporate the 23,000 foreigners who obtained residency permits during the 2014 regularisation campaign (MCMREAM, 2015 in Reference 209Benjelloun, Alioua and FerriéBenjelloun 2017b),Footnote 8 and whether they also include European irregular migrants. In 2015, French authorities counted almost 49,000 French people as stably residing in Morocco, and a further 20,000 living there for at least a part of the year. In 2013, almost 7,400 Spanish migrants were registered with their consular authorities in Morocco (Reference MounaMouna, 2016; Reference Therrien and PellegriniTherrien & Pellegrini, 2015). Given that the 2014 census counted 33,615 European residents, it is reasonable to suppose that at least 22,000 French and Spanish migrants were not captured in official Moroccan records (otherwise, French and Spanish migrants alone would account for 67 per cent of all foreign residents in Morocco).

Table 1 Evolution of the number of foreign residents in Morocco 1994–2014

| Demographics | 1994 | 2004 | 2014 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total population | 26,073,717 | 29,891,708 | 33,848,242 |

| Total foreigners | 50,181 | 51,435 | 84,001 |

| - From Europe | / | Ca 23,609 (45.9%) | 33,615 (40%) |

| - From Maghreb | / | Ca 12,293 (23.9%) | 11,142 (1.3%) |

| - Other African countriesFootnote 9 | / | Ca 5,348 (10.4%) | |

| - Sub-Saharan Africa | 22,545 (26.8%) | ||

| % foreigners over total population | 0.19% | 0.17% | 0.25% |

One fact risks being overshadowed by this migration number game: that immigration has little demographic relevance in Morocco. According to Moroccan censuses, the number of foreign residents in Morocco decreased from 529,000 individuals in 1952 to 51,435 in 2004. The number rose once again up to 84,001 in 2014. Although the census does not account for all the foreigners living in the country, I agree with Natter that “even higher estimates of around 200,000 migrants do not challenge the overall conclusion that immigration remains a minor phenomenon in Morocco – especially when considering the size and continuous growth of Morocco’s emigrant population, estimated at 4 million in 2012” (Reference NatterNatter 2018, 7) and – I would add – when considering that Morocco counts an overall population of over 33 million people.

Narrating the ‘Immigration Nation’

The construction of a regime of truth which manufactures Morocco into an ‘Immigration Nation’ relies on discourses that, as natural as they might appear, are produced according to rules of formation that are politically and historically situated (Reference FoucaultFoucault 2002). In fact, most reports, websites, or leaflets produced by aid-funded organisations begin with statements along these lines: “2013 marked a turning point in the migration policy of Morocco – a country which over the last 20 years has increasingly become a transit and host country for immigrants and refugees” (GIZ n.d.). In a similar vein, the European Commission states that “Morocco is characterised by the fact that it is at the same time a country of emigration, transit and, more recently, of asylum and settlement for migrants” (European Commission 2016, 3, translation by author). The Swiss Cooperation defines the moment in time when this transformation occurred: “Morocco […] has always been a transit country [for migrants heading] towards Europe. The closure of European borders transformed Morocco into a host country for an increasing number of irregular migrants, asylum-seekers, and refugees” (Confédération Suisse 2015, translation by author). The website of the Monaco Development Cooperation states “Due to its strategic position and following the deterioration of the political stability and socio-economic situation of many countries in sub-Saharan Africa and the Arab World, Morocco became a point of transit, even of settlement by default, for many asylum seekers and for economic migrants on their way to EU countries” (Principauté de Monaco 2017, translation by author). Again, the European Commission states:

The population of foreigners in Morocco is estimated around 86,000 people (according to the Haut Commissariat au Plan), including foreigners, expatriates residing in Morocco, and irregular migrants. For what concerns the irregular migrants, mostly sub-Saharan nationals, estimations varied (before the regularisation campaign) between 25,000 and 45,000 people […]. Otherwise, the unstable situation in the Middle East and notably the war in Syria […] has [sic] generated an increase of the flow of people coming from the region and potential candidates for refugee status in Morocco.

The production of these discourses are pervaded by “notions of development and evolution: they make it possible to group a succession of dispersed events, to link them to one and the same organizing principle, […] to discover, already at work in each beginning, a principle of coherence and the outline of future unity” (Reference FoucaultFoucault 2002, 24). Donors, NGOs, and IOs share a very consistent and selectively historicised idea of Morocco’s migration profile and transition. According to their accounts, immigrants appeared in Morocco between the late 1990s and the early 2000s, when the consequences of European border control policies transformed the Alaouite Kingdom into a spatial overflowing of the Old Continent. Implicitly, immigration in Morocco is therefore reduced to the presence of people moving from what policymakers have resorted to call ‘sub-Saharan’ Africa towards Europe.

In The Anti-Politics Machine, James Ferguson remarks that development organisations often produce simplified portrayals of the realities that they intervene in. Like the descriptions of Morocco which I previously evoked, the ways in which aid agencies simplify the economic, social, and political context of a country tend to repeat a similar model, with “mistakes and errors [that] are always of a particular kind, and they almost invariably tend in predictable directions. The statistics are wrong, but always wrong in the same way; the conceptions are fanciful, but it is always the same fantasy” (Reference FergusonFerguson 1994, 55). What we could easily dismiss as poor knowledge production is, upon closer inspection, not coincidental, but rather politically productive. Ahistorical representations of reality allow aid agencies to avoid engaging in politically sensitive discussions about political responsibilities for processes of predatory accumulation, dispossession, and inequality (Reference FergusonFerguson 1994). As Timothy Mitchell writes in his book on techno-politics in Egypt, international development reports do not only tend to leave politics aside, but also tend to leave out the political role played by the very agencies that produced the report in the first place (Reference MitchellMitchell 2002). The production of a sanitised portrayal of economic development in aid-recipient countries is instrumental to carving a space for aid agencies’ operations. Development expertise, which portrays itself as technical and non-political, steps in to fix problems that are technical and not political. For problems to be technical, politics needs to be left out of the representation (Reference FergusonFerguson 1994; Reference MitchellMitchell 2002).

The migration reports reproduced above, however, do not leave politics entirely out of the picture, but rather selectively bring it in. Stating that the presence of migrants in Morocco is a ‘recent’ or a ‘new’ phenomenon means reducing the experience of immigration in Morocco to the ‘transit’ and ‘spatial entrapment’ of those migrants who want to reach Europe crossing the Spanish–Moroccan border. This discourse is oblivious to the North–South migration that accompanied colonialism, as well as to the population of European immigrants that currently live in Morocco. In other words, the history of immigration in Morocco is modelled according to the history of migration securitisation in Europe: Morocco became a country of (‘sub-Saharan’) immigration when irregular migration became a problem in Europe (Reference PeraldiPeraldi 2011).

The representations of migration in Morocco conveyed by the migration industry are at odds with the existing statistics on the presence of foreigners in the country that I presented in Table 1. Interestingly, however, donors’ reports do not ignore existing figures about immigration in Morocco. The data on migrant presence in Morocco are produced and used by European, EU, and Moroccan institutions precisely to contextualise and justify their actions in the field of migration control. In 2016, the European Commission quoted figures from the 2014 census and sources estimating that 25,000–40,000 irregular migrants live in the country as part of its Executive Decision to allocate a €35 million budget support to Morocco for the implementation of the new migration policy (European Commission 2016) (see Chapter 1). When continuously confronted with the numbers, it is not unusual for institutional actors to admit that the number of immigrants in Morocco is quite low. In a booklet distributed to the Conference for the Third Anniversary of the National Strategy of Immigration and Asylum, the Moroccan Ministry of Migration itself stated that “regular migratory flows increase [in Morocco] […], even if the volumes remain weak” (MCMREAM 2016, 15). A former employee of the IOM Morocco stated that after the organisation started looking into the situation in the borderlands in 2012, they realised that the number of migrants in Northern Morocco was quite small.Footnote 10

Asking why such an image of immigration in Morocco has been produced despite statistical evidence is misleading. Data, to put it simply, are not neutral. The interpretation of statistics by policymakers is situational and inherently political, as data are produced and manipulated within pre-established power structures (Reference Leite and MutluLeite and Mutlu 2017). Data are read in order to fit an established discoursive practice around immigration in Morocco. This, of course, does not mean that I believe that there are statistical standards against which a certain country can be declared as an ‘immigration’ country or not. Rather, the use of the label of ‘immigration country’ in Morocco is linked to the presence of a population group considered ‘threatening’ to European borders. Discussing the quantitative mismatch between migrant presence and the political salience of migration in Morocco, Fabrice, an academic and senior development consultant whom I interviewed in July 2016, commented:

I mean in purely objective terms, when you look into Africa the migration potential is so huge that it is scary, I mean in the sense … for everybody, whichever establishment you have, you see what is happening with 1 million Syrians arriving in Europe? I mean 1 million! Nigeria alone every year has a 5 million population increase, so it is not so difficult imagining 5 million arriving … and the only way to avoid it is to have tight borders and cooperating with neighbouring countries and then, because of this, does it make sense to mobilise so many resources for a few thousands who are there? No, it is not for those few thousands, it is for the many millions that are behind [them]. This – and you can accept it or not – makes sense somehow.Footnote 11

The representation of Morocco as an ‘Immigration Nation’ has not been produced by ignoring the numbers, but by interpreting the numbers in an extremely securitised way. Enduring stereotypes about an incipient “invasion” (de Reference HaasHaas 2008) seem to be a determinant in structuring the orientation, workings, and priority areas of the migration apparatus in Morocco. Concerns about the ‘migration potential’ of Africa merge with an equally enduring “myth of transit” (Reference Cherti and GrantCherti and Grant 2013), which considers African foreigners in Morocco as a potential group of clandestine migrants en route to Europe. During an interview, an officer of the EU delegation in Rabat stated bluntly that concerns over transit were at the basis of the EU–Morocco cooperation over the implementation of the new migration policy:

The fact that Morocco has launched the National Strategy on Immigration and Asylum means that [the country] is taking a big responsibility. They consider that the issue is of their concern, and this means sharing the vision of the EU, which says to origin and transit countries “this concerns us all”. Morocco is one of the very few countries that takes this responsibility and this budget support is a political response which means “we know that these migrants were heading to Europe and therefore we want to contribute”.Footnote 12

In this securitised puzzle of migration control, the need to transform ‘sub-Saharan migrants’ into a sector of intervention in their own right is not based on the number of migrants actually living in Morocco, but on the number of migrants who could arrive – and, implicitly, who could move to Europe. Racism and xenophobia permeate the way (white) decision makers interpret facts and evidence concerning black people and charge them with political meanings and feelings of ‘threat’. This does not happen because evidence and facts are overlooked, but because they are interpreted “within a racially saturated field of visibility” (Reference Butler and Gooding-WilliamsButler 1993, 15). This transforms the relation between the privileged and those impacted by the system, those armed and those unarmed, the perpetrators and the victims. A court can feel entitled to judge a black man beaten by the police while seemingly unarmed and unreactive because he is visualised as a potential offender (Reference Butler and Gooding-WilliamsButler 1993). Spanish policemen can feel legitimised to shoot a group of black people swimming towards Spanish shores to avert the risk of migrant ‘invasion’ (Butler, in Reference Artigas and OrtegaArtigas and Ortega 2016).Footnote 13 In the same way, aid agencies transform a security concern originating in Europe into a hegemonic representation of immigration in Morocco. This occurs through a racialised manipulation of facts and figures. In this way, policymakers attribute more political salience to estimations of ‘sub-Saharan’ presence in the country due to a presumed ‘transit’, or ‘potential’, ‘future’ magnitude. The ‘threat’ is therefore never real but is always considered as incipient. And it is the blackness of the ‘potential migrants’ that justifies and normalises the construction of a migration industry, based on concerns over migrants who are not there, but who might be.

Performing the ‘Immigration Nation’

Manufacturing Morocco into an ‘Immigration country’ is not only a matter of discourse, but is also largely a matter of performance (Reference FoucaultFoucault 2002). Discourses about immigration in Morocco as a ‘sub-Saharan’ experience feed into a series of material practices which give this idea substance and form, stabilising it over a protracted period of time. The construction of the political through its performance is the product of the overlap between mundane and spectacular acts, “articulated through institutions, signifiers and services that materially constitute and discursively (re)produce political authority” (Reference Martínez and EngMartínez and Eng 2018, 237). The performances subsuming political infrastructure should not, however, be understood as pre-emptively arranged. Performativity is led by “improvisation,” “a form of individual adjustment of pre-given scripts in order to suit the needs of a particular context” (Reference JeffreyJeffrey 2013, 35). The securitisation of migration is a highly performative – and improvised – process. The following two sections will highlight how two events (the Ceuta and Melilla events in 2005 and the announcement of the new migration policy in 2013) durably structured the migration industry according to conceptions about immigration in Morocco as a ‘transit’, and then as a ‘settlement’ phenomenon.

The Ceuta and Melilla Events, and the Production of Transit

The Ceuta and Melilla events in 2005 constituted a key step in the construction of a public spectacle and awareness of ‘sub-Saharan’ migration in Morocco (Reference PeraldiPeraldi 2011). From knowledge available to specialised humanitarian organisations (MSF 2005; MSF España 2003) or to militant and advocacy groups (La Cimade and AFVIC 2005; Reference Maleno GarzonMaleno Garzon 2020), the presence of West and Central African migrants in Morocco, and the institutional repression enacted against them, became information within the public domain. The public exposure of suffering and violence triggered not only the solidarity of activist groups, but also the response of aid agencies (Reference PeraldiPeraldi 2011; Reference ValluyValluy 2006, Reference Valluy2007a). The Ceuta and Melilla events thus transformed ‘transit’ into the formative principle organising the development and humanitarian apparatus in Morocco – both in terms of its targeted beneficiaries and of its areas of operation.

Donors, NGOs, and IOs explicitly identified ‘transit’ migrants as a group of beneficiaries in project titles, fact sheets, and official communiqués (Reference KhrouzKhrouz 2016a; Reference PeraldiPeraldi 2011). For example, the International Federation of the Red Cross and of the Red Crescent got funding from the EU to implement a project focusing on “Improving the protection and living conditions of international migrants (pushed back or in transit) and of those made vulnerable by migration in North Africa” (Europe Aid 2008, emphasis by author). Between 2011 and 2013, the EU funded another project called “Reinforcing the protection of the rights of migrants in a transit country, Morocco” and implemented by the INGO Terre des Hommes in partnership with the Moroccan NGOs GADEM, and Oum El Banine (Reference KhrouzKhrouz 2016a, emphasis by author). In the section on ‘Context and Beneficiary Population’, the 2006 Country Operations Plan of UNHCR Morocco specified that:

… due to its geographic location as well as vast borders, Morocco has become a point of transit for many asylum-seekers as well as for economic migrants heading for Europe, mainly from Sub-Saharan countries, of which many are affected by conflict situations.

In this first phase, development and humanitarian organisations limited their programmes and projects to emergency operations. Donors, NGOs, and IOs focused on temporarily responding to migrants’ most urgent needs, rather than facilitating their integration in the country. This approach, which implicitly treated the presence of immigrants as temporary rather than structural, was influenced to a large extent by the attitude of Moroccan authorities vis-à-vis migration. At the time, the state refused to portray itself as a destination country for migrants and refugees (Reference NatterNatter 2014). Any activity supporting a possible long-term settlement of migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers – be it access to schools, support to labour integration, or similar activities – was explicitly considered a taboo (see Chapters 4 and 5). The UNHCR mission in Rabat, for example, encountered multifold problems with its activities: the government feared that anything durable “may make the country a magnet for sub-Saharans in search of a better life” (American Consulate of Casablanca 2006). The Moroccan authorities resisted granting official recognition to the UNHCR mission in Rabat, and did not seem keen on allowing refugees recognised by the UNHCR to stay in the country (American Embassy of Rabat, 2006a, 2006b).Footnote 14 In conversation with US diplomats, the UNHCR admitted fearing that even issuing plastic cards to refugees and asylum seekers would be perceived negatively by the government “as an indicator of a lengthy stay for the refugees and a permanent presence for UNHCR” (American Consulate of Casablanca 2006).

Similarly, an officer of the Swiss Development Cooperation argued that between 2007 and 2013 “the engagement [of Switzerland in the field of migration in Morocco] was purely humanitarian […]. Our logic was a logic of substitution because there was no public migration policy, and it was some NGOs that assisted migrants ….”Footnote 15 The officer of a drop-in centre for migrants operating in one of the main Moroccan cities recalled how this situation affected the services that the charity was able to offer:

Interviewee: The access to rights was extremely limited, the children could not go to school, access to healthcare services was extremely limited, there was a whole parallel system, and everything relied on NGOs, mostly on people’s self-improvisation …

Lorena: So, you offered much more emergency assistance …

Interviewee: Yes, for example, there is something that is very telling, another NGO and we offered classes for children. Children could not go to school, but we started from the principle that we could not leave the kids at home and bah, tant pis pour eux [too bad for them], they must stay at home and in the street. There were spaces so that the children did not have to spend the day at home and could follow something that looked like a school curriculum.Footnote 16

From a spatial point of view, the presence of development and humanitarian actors gradually came to include all the crucial migration points in the country. Between 2002 and 2008, assistance programmes were launched in Oujda, the gate to Morocco for migrants entering irregularly from Algeria and the first city that migrants could reach after having been deported by the Moroccan police in the desert; Rabat and, to a lesser extent, Casablanca, the two main economic centres in the country which host the majority of West and Central African migrants living in Morocco (Reference AliouaAlioua 2011a); Tangier and Nador, the two main points of departure for migrants heading to Europe by sea through the Mediterranean or by land through the two Spanish enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla.

By the early 2010s, “the political fiction of the ‘sub-Saharans in transit’” (Reference PeraldiPeraldi 2011, 11) was then solidly set: it included a set of targeted beneficiaries (the so-called ‘transit’ migrants), activities aimed at relieving their alleged temporary presence in the country (humanitarian assistance), and places of operation at the main migration stopovers in Morocco.

The New Migration Policy and the Production of Settlement

The announcement of the new migration policy marked a break in the way migration was approached, imagined, and governed in Morocco. This policy shift, and especially the two regularisation campaigns, allowed for the conceptualisation of ‘sub-Saharan migrants’ as no longer a transitory presence, but rather as a settled population. The fiction of transit gave way to the fiction of settlement in Morocco, casting attention on the figure of the ‘regularised migrant’.

The policy shift from ‘transit’ to ‘settlement’ has put the migration industry on a completely new track and revolutionised the limits of permissibility of the development and humanitarian apparatus. Before 2013, donors, NGOs, and IOs had to limit their mandates to emergency assistance. After 2013, donors, NGOs, and IOs were allowed to expand their operations to promote initiatives facilitating the integration of migrants in Morocco. This meant focusing on the promotion of access to public services (see Chapter 4) and to the labour market (see Chapter 5), and on enhancing the capacity of civil society organisations and state authorities in supporting integration (Chapter 3). Programmes focusing on migrant integration have proliferated, and so have the Facebook pages, communication campaigns, and round-table discussions promoting the fight against xenophobia and sponsoring professional training courses for migrants and refugees. In 2015, the EU launched a programme called “Promoting the integration of migrants in Morocco.” From promoting basic assistance to “stranded migrants,”Footnote 17 the EU started allocating funding for healthcare coverage for regularised migrants (€2 million), the promotion of access to education (€2 million), the facilitation of healthcare assistance for vulnerable migrant women (€1.4 million), and the integration of migrants into the labour market (€3 million)Footnote 18 (EU Delegation in Rabat 2016).Footnote 19

The announcement of the new migration policy also produced a new spatialisation of ‘presumed settlement’ and ‘presumed transit in Morocco’. As a document produced by the European Commission in the framework of the EU Trust Fund for Africa argues:

Schematically, transit migrants would be attracted by border zones (mainly the [region of the] Oriental and the North) while settled migrants and migrants “temporarily” settled will likely be located in the big cities (Rabat, Salé, Kenitra, and Casablanca etc.), while new areas of settlement are developing (Fes, Agadir etc.).

This division is, again, fictitious, as it is constantly challenged both by migrants and by the state itself. Migrants living in marginal neighbourhoods of Rabat and Casablanca move to these cities to rest and earn money, and then move on to Tangier or Nador to attempt to cross the border (Reference BacheletBachelet 2016). Moroccan authorities, instead, displace migrants from the borderlands to cities in the Centre and the South, further increasing the circulation between the borderlands and the rest of Morocco.Footnote 20

After the announcement of the new migration policy, the performance of Morocco as a ‘transit country’ officially gave way to the representation of Morocco as a ‘settlement country’. This included a new set of targeted beneficiaries (the so-called regularised migrants), activities aimed at integrating them in the country, and imagined geographies of settlement coinciding with cities where the migrant presence was tolerated by the authorities. From discourse to practice, Morocco had officially become an ‘Immigration Nation’.

Conclusion

In the past decade, Moroccan and foreign scholars published two edited volumes about the diversity of immigrant communities in Morocco – the first one edited by Michel Peraldi in 2011, the second one by Nadia Khrouz and Nazarena Lanza in 2016. The two volumes were written with the specific purpose of dismantling mainstream, albeit deceitful, conceptions about immigration in Morocco as a ‘sub-Saharan’ fact (Reference Khrouz and LanzaKhrouz and Lanza 2016; Reference PeraldiPeraldi 2011). The introduction to the volume edited by Nadia Khrouz and Nazarena Lanza situates the intervention within ‘a particular context of reassessment of the modes of perception and management of foreigners in Morocco, accompanied by the announcement of a new migration policy in September 2013’ (Reference Khrouz and LanzaKhrouz and Lanza 2016, 1–2, translation by author). That scholars felt compelled to write not one, but two edited volumes to complexify the dominant discourse about Morocco as an ‘Immigration Nation’ is emblematic of the extent to which the figure of the ‘wild man at Europe’s gates’ (Reference AnderssonAndersson 2010) has become hegemonic in Morocco.

The aid industry participates into the construction of Morocco into a ‘new’, ‘black’, ‘irregular’, ‘transit’ ‘Immigration Nation’ through discoursive and non-discoursive practices. On the one hand, development and humanitarian actors diffuse and normalise narratives reducing processes of immigration into Morocco to the rise of ‘transit’ migration in the early 2000s, and neglect to place this migration within a broader history and geography of intra- and inter-continental mobility. I have argued that these narratives are charged with racial categories and inscribed within racialised relations of power, transforming ‘sub-Saharan migrants’ in Morocco into a mobile ‘threat’ on their way to Europe. On the other hand, the politicisation and racialisation of migration discourse in Morocco was also fostered by practices that structure the workings of the migration industry around notions of ‘transit’ and ‘settlement’. The Ceuta and Melilla events in 2005 and the announcement of the new Moroccan migration policy in 2013 were the pivotal events in this process: they first traced and then revolutionised the limits of permissibility and the spaces of action of the aid industry. By providing emergency assistance along the main migrant stopovers, development and humanitarian organisations entrenched the idea of Morocco as a transitory place of migration in aid practice. After 2013, emergency assistance gave way to activities aimed at favouring migrant integration. The next five chapters will examine how the aid industry has engaged into Morocco’s integration project.