Introduction

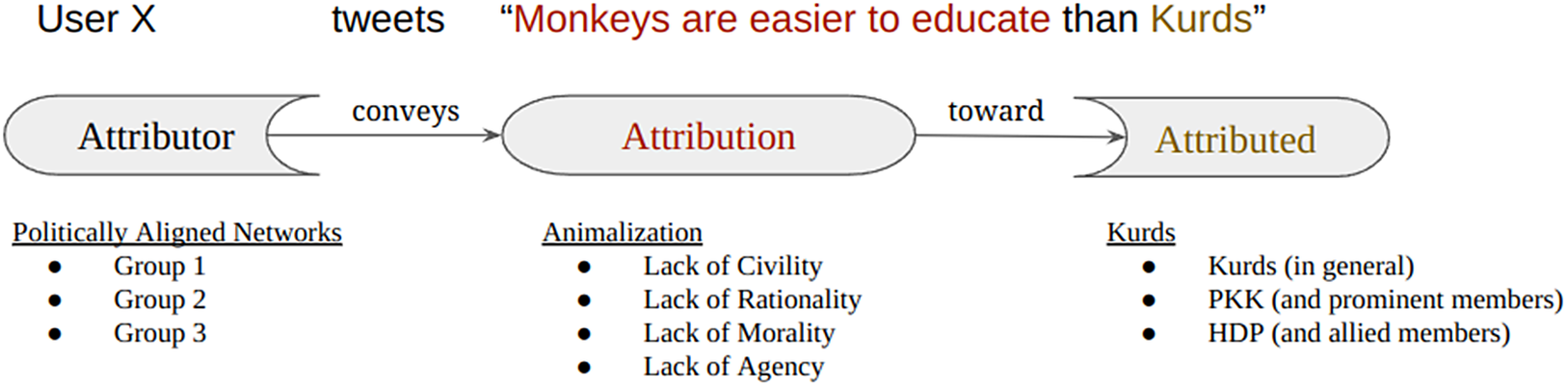

This study examines the phenomenon of animalizing dehumanization directed toward Kurdish people and organizations on Turkish-speaking Twitter when Kurds are explicitly mentioned. It seeks to answer the following questions: (a) what are the types and prevalence of animalizing dehumanization attributions to Kurdish people on Twitter, (b) who are the dehumanized and animalized groups and organizations when Kurds are explicitly mentioned, (c) what are the differences among animalizing dehumanization content creators? By using a large-scale Twitter data set, this research unravels general trends of animalization directed toward Kurds and rank orders ways of animalization, attributed subgroups, and attributors. Rather than studying individual animal metaphors separately, it merges all available animalization dictionaries from previous works, translates them into Turkish, and searches for almost every possible animalizing term in all tweets mentioning Kurds in the Turkish language on Twitter during a seven-month period. The attributor-attribution-attributed framework employed in this research can be seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Attributor-attribution-attributed framework.

This article starts by briefly explaining the Turkish-Kurdish conflict and the context of this study. Subsequently, it examines the literature on dehumanization and the use of animal references for dehumanizing purposes. Afterward, it argues that animalization serves to attribute a lack of supposedly “human” traits (rationality, civility, morality, and agency) to individuals and human groups. After discussing the previous literature on trait attribution and animalizing dehumanization, it presents the methodological approach to disclose attributed groups and attributors. It consequently examines the corpus, starting with focusing on the implied or stated lack of human traits about various Kurdish organizations. Later, it interprets the specific animal references used in the corpus and the difference in the use of such references between major political communities on Turkish-speaking Twitter. It concludes by summarizing findings and suggesting future avenues for further research.

This research finds that among the four supposedly lacking human traits, lack of civility and rationality are mostly attributed to Kurds as an ethnic group (or Kurdishness as an identity category), lack of agency is mostly attributed to HDP (legal political party), and lack of morality is mostly attributed to PKK (armed group). This study also establishes the first Turkish animalization dictionary to the best of knowledge. Finally, for future work, it asks whether such a pattern of attributing a lack of civility and rationality to people, lack of agency to the representative legal political party, and lack of morality to the armed group can emerge as a general theory in animalization studies in ethnic conflicts in different contexts.

The Turkish–Kurdish Conflict

The term Turkish–Kurdish conflict is used for denominating the conflict between Kurds and the Turkish State in relation to the “Turkification” of the region of Anatolia (Saatci Reference Saatci2002; Ünlü Reference Ünlü2016; Protner Reference Protner2018). Although the roots of the Turkish-Kurdish conflict can be traced back to the 19th-century Ottoman Empire (Yeğen Reference Yeğen2016, 366), the conflict has intensified following World War I when the Middle Eastern political map was redrawn, Kurdistan was partitioned without consultation (Radpey Reference Radpey2022), and the Turkish Republic was founded. The Kurdish Sheikh Said rebellion took place in 1925, just 15 months after the foundation of the Republic, and it was followed by the Ararat (1930) and Dersim (1937) rebellions. After passing through various stages in a multiactor setting that includes distinct insurgent groups, the conflict is still ongoing. The armed aspect of this conflict has been dominated by two main actors in the last decades: the Kurdish PKK (Partiya Karkerên Kurdistanê or Kurdistan Workers’ Party) and the Turkish State.

The PKK was founded in 1978 as a clandestine “Marxist-Leninist national liberation organization” (Özsoy Reference Özsoy2013; Yeğen Reference Yeğen2016). The PKK’s chief objective was “ending Turkish colonialism” (Yeğen Reference Yeğen2016, 372); however, the organization underwent a political transformation following the collapse of the Soviet Union (Gurses Reference Gurses2020). This transformation gained momentum following the arrest of the PKK leader, Abdullah Öcalan, which resulted in a paradigm shift for the PKK (Gurses Reference Gurses2020). This process led to peace negotiations between the PKK and the Turkish State. The negotiations were announced by the then Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan in 2012. The peace process was abolished shortly after the June 7 elections in 2015, and the level of violence has increased considerably after the failure of this process. Although the armed conflict was ongoing, the Kurdish legal political parties also became influential in the country’s political atmosphere starting from 1990. The parties were frequently banned by the Constitutional Court, and their members were arrested on many occasions (Casier, Jongerden, and Walker Reference Casier, Jongerden and Walker2011). As a result, the Kurdish political movement had to establish numerous legal political parties as substitute parties (Okudan Dernek Reference Okudan Dernek2014). The HDP (Halkların Demokratik Partisi or Peoples’ Democratic Party) was the representative of this movement as the third largest political party in the Turkish Parliament when this research was conducted.

As the largest legal representative of the Kurdish political movement, HDP was the target of violent attacks starting from 2015. Before the June 7 general elections in 2015, HDP suffered 176 attacks according to Human Rights Association (İHD); these attacks included seven armed assaults, five bomb attacks, and four arsons; as a result, six people were killed and 516 people were injured (İnsan Hakları Derneği Reference Derneği2015b). Between the June 7 elections and November 1 snap elections, 138 more attacks on HDP and its constituent organizations occurred (İnsan Hakları Derneği Reference Derneği2015a). During the same period, military operations in Kurdish cities resulted in the forced displacement of approximately 500,000 people (OHCHR 2017). Numerous racist attacks on Kurds that occurred during this period became a frequent trend afterwards. Recent research shows that an inferior status is appointed to Kurdish people (Corut Reference Corut2020) as well as to the Kurdish language (O’Driscoll Reference O’Driscoll2014) in Turkey in the context of ethnic subordination.

Similar to other recent cases (Walsh Reference Walsh2021), the atmosphere of political violence, state oppression, social discrimination, and racism that surrounds Kurdish people results in increased dehumanization on social media (Tutkal Reference Tutkal2022). This is also true for the use of animal references for purposes of dehumanization. This article examines such uses in Turkish-speaking Twitter posts that concern Kurds when Kurds are explicitly mentioned. By examining a large Twitter data set, it was possible to highlight the general trends of dehumanizing animalization directed toward Kurds in Turkish-speaking social media. The research demonstrates the ways in which the use of animal references when Kurds are explicitly mentioned, including specific animals and metaphors that are used for different ways of dehumanization and differing uses of animal references for dehumanization among users from different political communities, serve to dehumanize Kurds in Turkey as well as to dehumanize members of major Kurdish political organizations There is no prior academic work (in English or in Turkish) on the use of animal metaphors in Turkish political communication. There is no work dedicated to examining the phenomenon of animalizing dehumanization in Turkey either, with the exception of Tutkal (Reference Tutkal2022) who mentions it as a subcategory in his research on mutilation of the dead bodies of PKK militants and dehumanization of Kurds. Thus, the article seeks to fill the gap in the literature when it comes to animalizing dehumanization in Turkey while also seeking to make up for the absence of academic research on the use of animal references in Turkish political communication.

Animalizing Dehumanization

Dehumanization is “a denial that a certain group is ‘equally’ human, no matter how that ‘humanity’ is defined” (Savage Reference Savage2013, 144). It should be noted that dehumanization should not be considered “a static event” or “a fixed condition of being” but rather “an active condition of becoming,” which leads to the conceptualization of dehumanization as “cumulative” (Bustamante, Jashnani, and Stoudt Reference Bustamante, Jashnani and Stoudt2019, 322). This means that there are processes and structures of dehumanization and dehumanization cannot be reduced to isolated single actions. Haslam et al. (Reference Haslam, Loughnan, Kashima and Bain2009) distinguish two types of dehumanization based on an analysis of “what is being denied to people when they are dehumanised” (61). In this way, the authors differentiate between animalistic and mechanistic dehumanization (2009, 62–63). These two different forms of dehumanization correspond to two distinct senses of humanness, one based on human uniqueness and the other based on human nature. Animalization is the “likening of people to animals and the ascription of relatively bestial or barbaric characteristics to them” (Haslam et al. Reference Haslam, Loughnan, Kashima and Bain2009, 63), and in mechanistic dehumanization people are objectified or machine-like attributes are attached to them (Haslam et al. Reference Haslam, Loughnan, Kashima and Bain2009, 64). This framework was criticized by Tipler and Ruscher (Reference Tipler and Ruscher2014), who argue that it “does not appreciate the diverse range of dehumanizing metaphors” such as “metaphoric characterization of groups as predators versus prey”; “metaphors of pestilence, disease, insects, and vermin”; and metaphors of vegetables (2014, 217). Even though it is correct that Haslam et al.’s classification is unsuccessful in accounting for all kinds of dehumanization (vegetable metaphors are a good example of this), this research argues that the category of animalistic dehumanization is useful to classify a specific way of dehumanization.

Dehumanization results in the legitimation of political violence and “negative emotions that may increase motivation for violent action” (Wahlström, Törnberg, and Ekbrand Reference Wahlström, Törnberg and Ekbrand2021, 3290). Dehumanizing practices are especially common in times of war, which makes achieving successful reconciliation and peace extremely difficult (Tutkal Reference Tutkal2022, 179). It has been shown that “dehumanization allows for acts of violence that would usually be forbidden to be celebrated” (Steuter and Wills Reference Steuter and Wills2008, 38). Thus, dehumanization can be considered “a process of moral disengagement that legitimizes killing that would otherwise be unacceptable” (Savage Reference Savage2013, 151). That is why Savage (Reference Savage2013, 147) classifies dehumanization as a necessary but not sufficient condition of genocide. Indeed, dehumanization played an important role in previous genocides and massacres (Bar-Tal Reference Bar-Tal1990; Haslam et al. Reference Haslam, Loughnan, Kashima and Bain2009).

Discourses play a crucial role in the reproduction of racist practices as well as in their legitimation (van Dijk Reference van Dijk1993, 13; Reisigl and Wodak Reference Reisigl and Wodak2000, 1). In relation to this, Essed (Reference Essed and Solomos2020) argues that dehumanization and humiliation “help sustain most if not all of forms of structural inferiorization and marginalization” (443). As a result, dehumanization and dehumanizing discourse become an important aspect of systemic racism and ethnic discrimination (Memmi [Reference Memmi1982] 2000, 116; Hund Reference Hund and Kronfeldner2021, 231), which is why racialized dehumanization appears as a subcategory of dehumanization (Bustamante, Jashnani, and Stoudt Reference Bustamante, Jashnani and Stoudt2019).

Throughout history, animal metaphors have been used for preparing “the ground for aggression and collective violence” (Andrighetto et al. Reference Andrighetto, Riva, Gabbiadini and Volpato2016, 630). Animal metaphors were especially common during genocides and massacres (Haslam, Loughnan, and Sun Reference Haslam, Loughnan and Sun2011, 312; Tipler and Ruscher Reference Tipler and Ruscher2014, 216). Animalization of the “other” as a way of dehumanization has been noted in various studies (Steuter and Wills Reference Steuter and Wills2010; Kovacevic Reference Kovacevic2017; Kronfeldner Reference Kronfeldner and Kronfeldner2021; Machery Reference Machery and Kronfeldner2021). Even though animalizing dehumanization sometimes occurs for attributing seemingly positive qualities, such as physical abilities, it has been shown that underlining such physical qualities usually implies a lack of intellectual skills and cognitive abilities, as in the case of Black athletes (Walzer and Czopp Reference Walzer and Czopp2011; Haslerig, Grummert, and Vue Reference Haslerig, Grummert, Vue, Brug, Ritter and Roth2019). Thus, seemingly positive animalization may imply lack of rationality or even civility.

Dehumanizing use of animalization necessitates an a priori belief that humans are not animals (Memmi [Reference Memmi1982] 2000); thus, it must be examined in relation to the socially constructed dichotomy of human and nonhuman (Latimer and Miele Reference Latimer and Miele2013). This dichotomy is the result of attributing certain qualities to humans that supposedly differentiate them from other animals. The dichotomy of human and nonhuman becomes interwoven with the dichotomy of us and others by considering the other “less human” and more “animal-like” (Tutkal Reference Tutkal2022). These qualities that supposedly mark the differences between human groups and animals will be examined in more detail because they are fundamental for this research. At this point, it is important to note that there are research findings indicating that people “attribute to the ingroup what it means for them to be human, independent of the valence of these characteristics” (Kronfeldner Reference Kronfeldner and Kronfeldner2021, 10), which means that dehumanization is context specific.

Animalistic Dehumanization: Attributing Lack of Human Traits

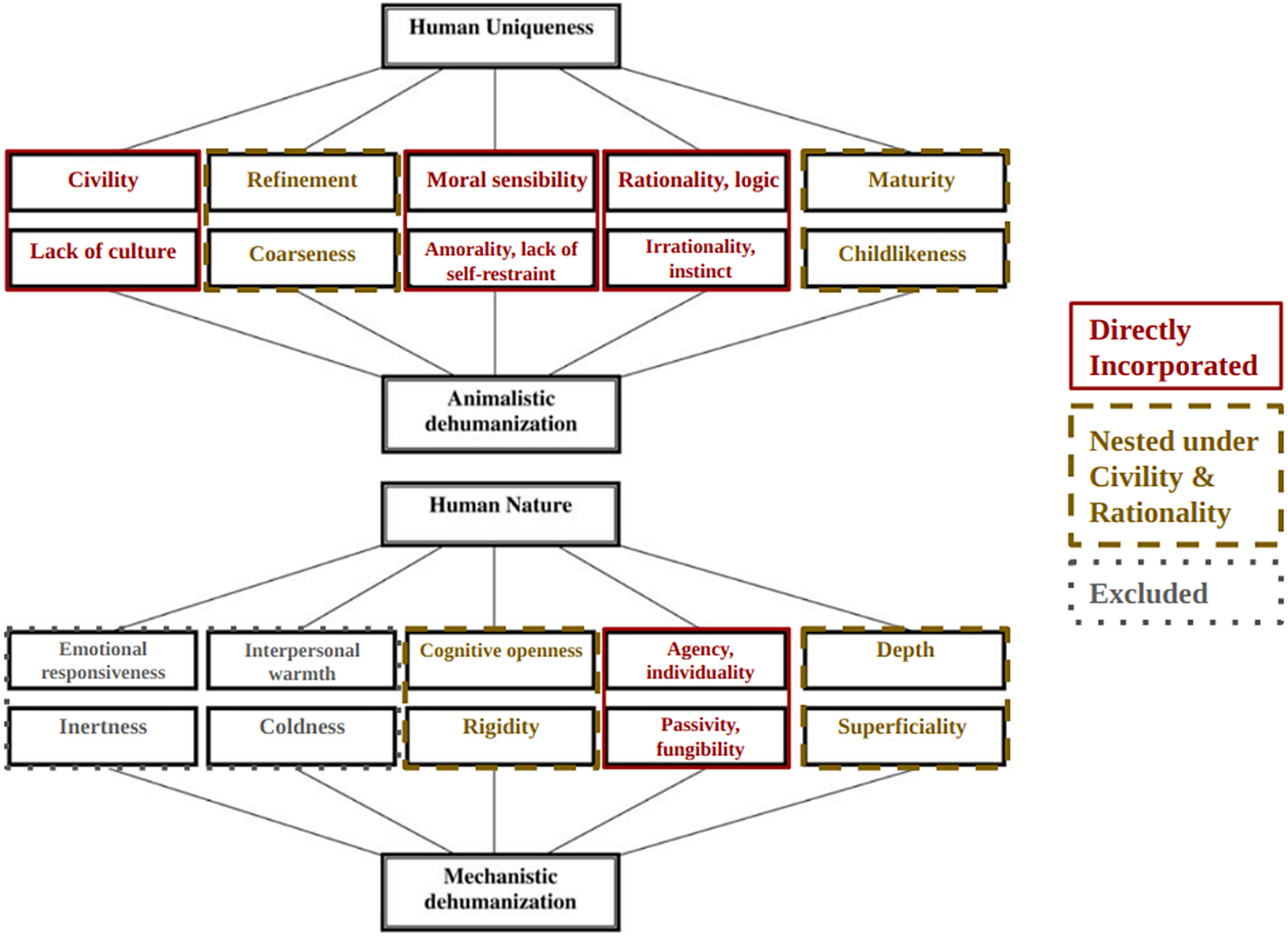

Animalization, as well as other types of dehumanization, seeks to attribute a lack of supposedly human traits to the other, which, in turn, results in the reproduction of ongoing social hierarchies in a way that makes possible future attempts of dialogue and reconciliation hard to succeed. Trait attributions are commonly used for assessing the perceived level of dehumanization (Kteily et al. Reference Kteily, Bruneau, Waytz and Cotterill2015, 903). Following the schemas of Haslam et al. (Reference Haslam, Loughnan, Kashima and Bain2009), this study conducted an initial screening of data from which four general categories of human traits emerged: agency, civility, morality, and rationality. Figure 2 displays the reorganization of the categories of Haslam et al.

Figure 2. Reorganization of categories based on Haslam et al. (Reference Haslam, Loughnan, Kashima and Bain2009).

The claim here is that lack of these attributes may legitimize and justify discriminatory behavior or even direct use of violence. Attributing the lack of one or more of these traits can help legitimize subordination, unequal power relations, structural racism, ethnocides, genocides, social and political exclusion, sexism, or ageism.

Rationality

Rationality is considered a uniquely human attribute, and lack of rationality can result in the animalization of individuals and human groups (Haslam et al. Reference Haslam, Loughnan, Kashima and Bain2009, 62). The roots of this supposed correlation between humanness and rationality can be traced back to certain fundamental European scholars. For example, for Kant “humanity” and “capacity for rational agency” are interchangeable ([1797] Reference Kant1991, 24) to the level that he denominates human (or “man” as in the original text) as “animal rationale” (230). Underlining the rationality of “man” as “his” fundamental trait can be traced in various important European thinkers, which can be manifested by stating that “the names man and rational, are of equal extent, comprehending mutually one another” (Hobbes [1651] Reference Hobbes1998, 22) or arguing that “to be rational pertains to the essence of man” (Aquinas [1485] Reference Aquinas1947, 192) and claiming that “when ‘man’ is attributed to anyone, a rational nature is likewise attributed to him” (Aquinas [1485] Reference Aquinas1947, 205).

This contrast between rationality and irrationality was used to establish and carry out structures of racism and oppression based on European supremacy. As a result, “the oriental” (Said Reference Said2003, 40) and “the Indian” (León-Portilla Reference León-Portilla2010, 282) were considered “irrational” compared with the “rational” European man. Denying cognitive agency is a way of dehumanization in which out-groups are seen as “irrational and unintelligent” (Tipler and Ruscher Reference Tipler and Ruscher2014, 219).

Some examples of animalization that attributes irrationality from the corpus are likening or comparing to rabid dogs, likening people to herds or sheep, or making references to fish and other animals considered intellectually inferior. In these examples, a supposed “lack of rational capacity” is attributed to people, which implies that the said people are not capable of engaging in rational decision-making processes. This may result in justifying unequal power relations and subordination of racialized people based on their supposed lack of cognitive skills. After all, lack of rationality may justify political exclusion, subordination, or colonization because subjects that lack rationality are considered in need of guidance from rational subjects that can take care of them, similar to how a shepherd guides and takes care of the herd.

Civility

Civility is considered a uniquely human attribute, the lack of which results in animalization (Haslam et al. Reference Haslam, Loughnan, Kashima and Bain2009, 62). The supposed correlation between civility and humanity has deep roots in Western thought, as it is summarized by Durkheim, “man is man only because he is civilized” ([1912] Reference Durkheim1995, 214). The dichotomy of “the civilized” versus “the savage” is considered one of the four varieties of dehumanization by Stuurman (Reference Stuurman and Kronfeldner2021, 39). Thus, painting individuals and human groups as “uncivilized” and attributing a lack of civility to them is a way of dehumanization. Considering Kurds “uncivil” compared with civilized Turks has also occurred throughout the history of the Turkish–Kurdish conflict (van Bruinessen Reference van Bruinessen and Andreopoulos1994; Ünlü Reference Ünlü2018). One result of this is the fact that many Kurdish words became insults in Turkish that are used to indicate being uncivilized (Yarkin Reference Yarkin2020, 2720).

Claims of the lack of civility of Kurds are presented in various ways in our corpus. Common examples are stating that Kurds “multiply,” “breed,” or “reproduce” fast, likening them to monkeys and oxen; accusing Kurds of bestiality; or arguing that they lack civilized values such as cleanness.

Lack of civility justifies discriminatory treatment because the uncivil is considered not trustworthy. Thus, being associated with barbarians or incivility may imply an impossibility of establishing civil relations. As a result, rules of courtesy and honor that exist among the civilized populations do not apply to people that are deemed uncivil, which legitimizes hostility and violence toward such people. Because lack of civility implies being a danger to civilized peoples, violence toward them can be justified as supposed acts of self-defense coming from the civilization.

Morality

Moral sensibility is a trait that Haslam et al. (Reference Haslam, Loughnan, Kashima and Bain2009, 62) consider a uniquely human attribute. Thus, individuals or groups denied human uniqueness may be considered amoral (Tipler and Ruscher Reference Tipler and Ruscher2014, 216). Morality is considered an important feature of humanness; as has been stated by Hume ([Reference Hume1739] 2007, 394), “It requires but very little knowledge of human affairs to perceive, that a sense of morals is a principle inherent in the soul, and one of the most powerful that enters into the composition.” It is also important to note that moral distinctions are considered categorically different from reason, which was again stated by Hume ([Reference Hume1739], 2007, 295): “Moral distinctions, therefore, are not the offspring of reason. Reason is wholly inactive, and can never be the source of so active a principle as conscience, or a sense of morals.”

Being deceitful or using means that are considered dishonorable to achieve their goals are claims that allow for arguing lack of morality. To this end, animals such as jackal, hyena, tick, and snake, as well as parasites, were frequently used in the corpus. Dogs and pigs were also mentioned for attributing immorality. Lack of morality may attribute “evilness” or “treacherousness” to otherized people, which can justify violent attacks toward them. Similar to the claims of “lack of civility,” arguing for “lack of morality” may also serve to mark the animalized out-group as a threat to the in-group. Attributing lack of “morally redeeming qualities” as an important part of the racialization of Kurdish people in Turkey was previously reported by Ergin (Reference Ergin2014, 331).

Agency

Even though Haslam et al. (Reference Haslam, Loughnan, Kashima and Bain2009) consider agency a feature of human nature and, thus, attributing lack of agency or passivity a process leading to mechanistic dehumanization (2009, 63), this research argues that these attributions may also lead to animalization. Passivity indicates lack of individuality (Haslam et al. Reference Haslam, Loughnan, Kashima and Bain2009, 63), and social actors become quantifiable when passivity is attributed to them (Pardo Abril Reference Abril and Graciela2005, 183), which is a recurring theme in various cases of animalization. Tipler and Ruscher (Reference Tipler and Ruscher2014, 218) agree that agency cannot be limited to human uniqueness or human nature and the agency may be attributed as an affective, behavioral, and cognitive agency (224). In this way, out-groups may be denied cognitive agency, which results in perceiving them as passive or submissive (Tipler and Ruscher Reference Tipler and Ruscher2014, 219). One example of how attributing passivity can result in dehumanization is the “myth of Jewish passivity” during the Holocaust (Kronfeldner Reference Kronfeldner and Kronfeldner2021, 13).

Animal metaphors that indicate obedience, dependency, or lack of agency, in general, are considered dehumanizing in this research. Some metaphors of cattle, dogs, donkeys, sheep, or other domesticated animals are examples of it. Accusing individuals and human groups of being “dogs” of actors that are considered more potent (United States, Israel, etc.) were especially common in the corpus. By claiming lack of agency, demands for compliance become justified. Not having agency means not being considered equal humans to engage in dialogue. Arguing for lack of agency instrumentalizes humans and human groups; after all, if an individual or a human group lacks agency, this means that their voice can be overlooked. Because lack of agency implies the impossibility of negotiation, it may justify violence toward the animalized groups as the only viable option.

Methodology

The methodology follows three steps: (1) annotation and estimation of animalizing dehumanization content, (2) community detection, and (3) measuring narrative differences among major communities. To provide the details of the first step, this section starts with going over the data collection, annotation, and estimation framework. Then, it highlights how tightly knit retweet communities in the data set were detected by describing the Louvain algorithm (Blondel et al. Reference Blondel, Guillaume, Lambiotte and Lefebvre2008) and how this study gets inspiration from previous related works. Finally, it outlines the methodological approach in detecting differences in each community’s use of animal words when Kurds are explicitly mentioned.

Data Collection

The Turkish language has an agglutinative morphology (Oflazer Reference Oflazer1995), and Twitter API end points are designed for the exact match of words. To partially overcome this challenge, a keyword list of the Turkish word “kürt” and its variants with various suffice adding up to 161 unique keywords was composed (Appendix A). Tweets containing any of these words were collected by using the track end point of Twitter API v1.1.Footnote 1 The data set spans tweets from November 8, 2020, to May 31, 2021. Tweets between March 10, 2021, and March 21, 2021, were missed due to a downtime in data collection pipeline. In this way, 2,529,488 tweets containing the word “kürt” tweeted from 534,548 unique Twitter users were collected. The data set is available at Harvard Dataverse (Tutkal Reference Tutkal2023).

Extracting Turkish Animalization Words

A Turkish dictionary of animal words that are commonly used for dehumanizing animalization was constructed based on prominent previous studies from different languages in the field (Talebinejad and Dastjerdi Reference Talebinejad and Dastjerdi2005; Goatly Reference Goatly2006; Viki et al. Reference Viki, Winchester, Titshall, Chisango, Pina and Russell2006; Loughnan and Haslam Reference Loughnan and Haslam2007; Haslam, Loughnan, and Sun Reference Haslam, Loughnan and Sun2011; Andrighetto et al. Reference Andrighetto, Riva, Gabbiadini and Volpato2016; Wahlström, Törnberg, and Ekbrand Reference Wahlström, Törnberg and Ekbrand2021), as there is no study on Turkish cases to our knowledge except for the short list of keywords used by Tutkal (Reference Tutkal2022). Lists of words used in these studies were collected and translated into Turkish. A few other animal words that are specific to the Turkish language in their negative connotations were also added—for example, spider-brained (örümcek beyinli) to call someone’s ideas out as backward and nuanced variants of dogs (it, çomar). As a result, 135 Turkish animalization words were collected. The full list of words in English and Turkish can be found in Appendix B.

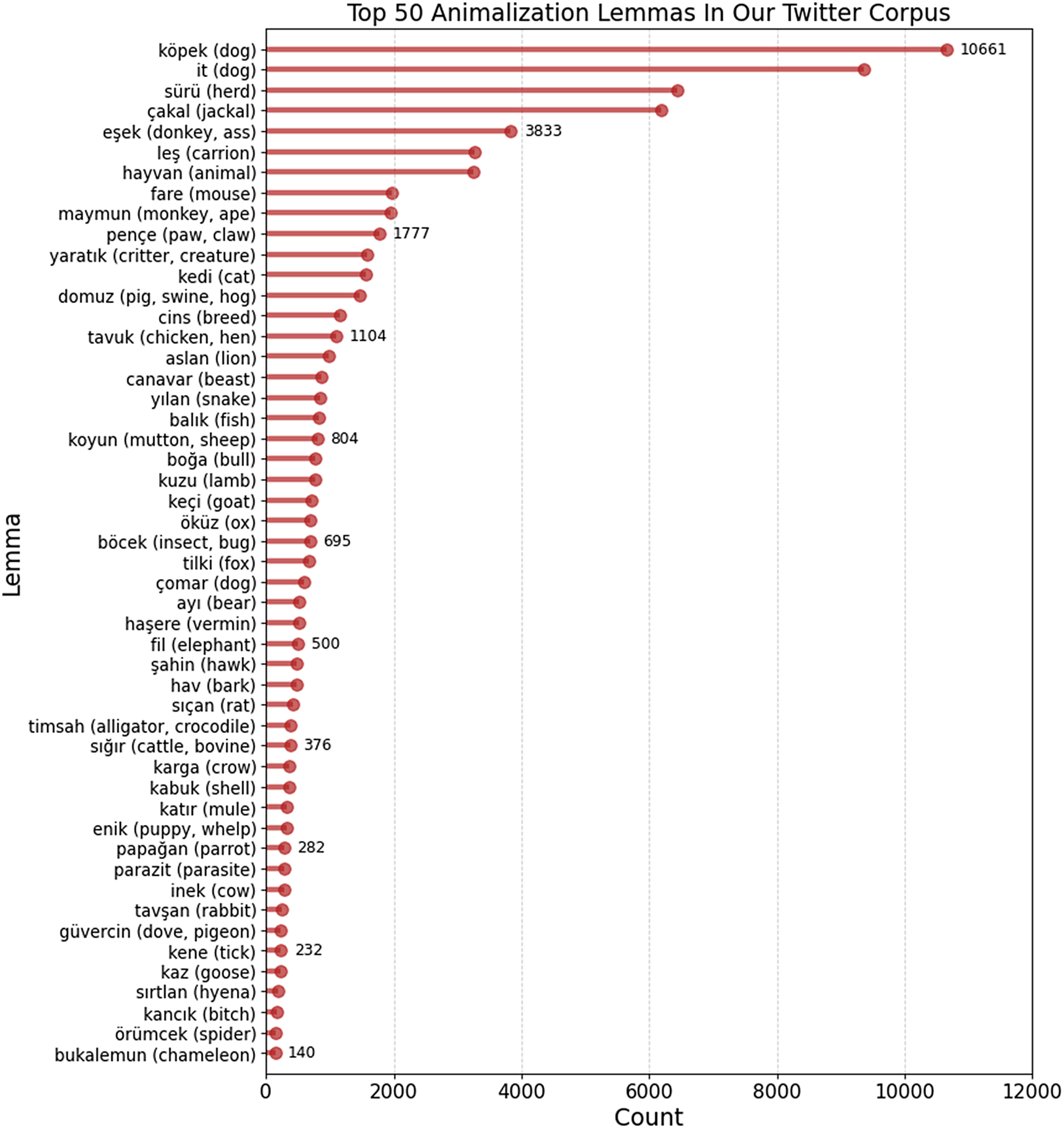

To mark the appearance of each animal word in tweets, the spell checker, lemmatization, and part-of-speech tagging tools of Zemberek, an open-source Turkish natural-language-processing library, were used (Akın and Akın Reference Akın and Akın2007). The spell-checking tool helped correct numerous mispronounced animal words appearing in tweets. The lemmatization tool allowed for matching animal words that have suffices in the tweet. Finally, part-of-speech (POS) tagging was crucial in differentiating a few animal words that have multiple meanings depending on their POS tags (it - noun means dog, it - verb means push). The top 50 appearing animal words can be found in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Top 50 animalization lemmas.

Appearance counts of the complete list (135 words) are available in Appendix C.

Annotation

An annotation task on sampled tweets was conducted using the tags of the aforementioned five categories—namely, negativity of animalization, lack of civility, lack of morality, lack of agency, and lack of rationality. The author of this article annotated randomly 100 tweets for each of the top 50 occurring animal lemmas with a colleague who wishes to stay anonymous but has offered significant contributions to this research. Annotators were also required to write the target of the animalization in a free text form. Later, incidences of dehumanizing animalization that was directed at target entities (Kurds, HDP, and PKK) were aggregated when possible and the rest was ignored. The aggregated dictionary of target entities is available in Appendix D.

Annotators worked on a common animal lemma (fare [tr], mouse [eng]) to validate the agreement between them. After validating the agreement on the word “mouse,” they moved on to other lemmas separately. In the last iteration, their Cohen’s kappa interrater reliability scores were the following: negativity of animalization is 1.0, lack of civility is 0.8195, lack of moral sense is 0.9549, lack of agency is 0.9535, and lack of rationality is 0.9240, which imply an almost perfect agreement between annotators. Both annotators’ results are made available at the provided link.Footnote 2

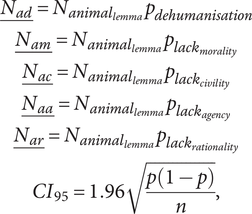

Subsequently, the number of tagged tweets among all tweets was reported with 95% confidence intervals by using stratified sampled tweets for each animal lemma as

$$ {\displaystyle \begin{array}{c}\underset{\_}{N_{ad}}={N}_{animal_{lemma}}{p}_{dehumanisation}\\ {}\underset{\_}{N_{am}}={N}_{animal_{lemma}}{p}_{lack_{morality}}\\ {}\underset{\_}{N_{ac}}={N}_{animal_{lemma}}{p}_{lack_{civility}}\\ {}\underset{\_}{N_{aa}}={N}_{animal_{lemma}}{p}_{lack_{agency}}\\ {}\underset{\_}{N_{ar}}={N}_{animal_{lemma}}{p}_{lack_{rationality}}\\ {}C{I}_{95}=1.96\sqrt{\frac{p\left(1-p\right)}{n}},\end{array}} $$

$$ {\displaystyle \begin{array}{c}\underset{\_}{N_{ad}}={N}_{animal_{lemma}}{p}_{dehumanisation}\\ {}\underset{\_}{N_{am}}={N}_{animal_{lemma}}{p}_{lack_{morality}}\\ {}\underset{\_}{N_{ac}}={N}_{animal_{lemma}}{p}_{lack_{civility}}\\ {}\underset{\_}{N_{aa}}={N}_{animal_{lemma}}{p}_{lack_{agency}}\\ {}\underset{\_}{N_{ar}}={N}_{animal_{lemma}}{p}_{lack_{rationality}}\\ {}C{I}_{95}=1.96\sqrt{\frac{p\left(1-p\right)}{n}},\end{array}} $$

where p is the rate of annotated (as dehumanizing animalization, lack of rationality, lack of civility, lack of morality, and lack of agency) tweets in the sample, N is the number of tweets that a certain animal lemma is in, and n is the sample size (100 for each animal lemma).The Ns and 95% interval thresholds of each animal lemma are simply summed when reporting numbers and confidence intervals on aggregate animalization targets (Kurds, PKK, HDP).

Community Detection

Community detection is a well-established quantitative technique in identifying densely connected entities in interaction networks (Fortunato Reference Fortunato2010). Retweet networks are known to disclose political alignments in Twitter data sets when community detection is applied to them (Conover et al. Reference Conover, Ratkiewicz, Francisco, Goncalves, Menczer and Flammini2011; Ozer, Kim, and Davulcu Reference Ozer, Kim and Davulcu2016). To understand dehumanizing animalization patterns at a mesoscopic scale, an off-the-shelf Louvain (Blondel et al., Reference Blondel, Guillaume, Lambiotte and Lefebvre2008) community detection algorithm was applied to the data set. Louvain is a multipass modularity-based community detection algorithm where modularity is defined as follows:

$$ Q=\frac{1}{2m}{\sum}_{i,j}\left({A}_{ij}-\frac{k_i{k}_j}{2m}\right)\delta \left({c}_i,{c}_j\right), $$

$$ Q=\frac{1}{2m}{\sum}_{i,j}\left({A}_{ij}-\frac{k_i{k}_j}{2m}\right)\delta \left({c}_i,{c}_j\right), $$

where

![]() $ {A}_{ij} $

defines the number of retweets between two users,

$ {A}_{ij} $

defines the number of retweets between two users,

![]() $ {k}_i $

and

$ {k}_i $

and

![]() $ {k}_j $

are the numbers of retweeted unique users of user i and j, and m is the number of retweet connections in the greater retweet network. Finally,

$ {k}_j $

are the numbers of retweeted unique users of user i and j, and m is the number of retweet connections in the greater retweet network. Finally,

![]() $ \delta $

is a step function that takes the value of 1 if user i and user j are put into the same community and 0 if user i and user j are put into different communities. In short, maximizing modularity implies putting pairs of users who retweet each other more often than by random chance (

$ \delta $

is a step function that takes the value of 1 if user i and user j are put into the same community and 0 if user i and user j are put into different communities. In short, maximizing modularity implies putting pairs of users who retweet each other more often than by random chance (

![]() $ \frac{k_i{k}_j}{2m} $

) in the same community and putting pairs of users who retweet each other less often than by random chance in different communities. Identifying communities of users equips us with the set of users who retweet each other more than they retweet others. Characteristics of animalization strategies of groups of politically like-minded users were reported through the gaze of community structure.

$ \frac{k_i{k}_j}{2m} $

) in the same community and putting pairs of users who retweet each other less often than by random chance in different communities. Identifying communities of users equips us with the set of users who retweet each other more than they retweet others. Characteristics of animalization strategies of groups of politically like-minded users were reported through the gaze of community structure.

To characterize the communities of users, a few aggregate popular Twitter accounts, hashtags, keywords, and URL news domains for the largest three communities were also reported.

Word Shift Detection

To characterize differences in use of animal lemmas by the largest three retweet communities, the shifterator library, a Python implementation of a recent work by Gallagher et al. (Reference Gallagher, Frank, Mitchell, Schwartz, Reagan, Danforth and Dodds2021), was used. Generalized word shift graphs provide insights on the most popular differing strategies of dehumanizing animalization across communities in a comparative fashion. The shifterator package computes the Jensen–Shannon divergence of two corpora and each word’s contribution to total divergence and, finally, plots a comparative report. It has been previously applied successfully to detect hashtag activism divergences across #blacklivesmatter and #alllivesmatter (Gallagher et al. Reference Gallagher, Reagan, Danforth, Dodds and Moreno2018), to disclose narrative differences in coordinated Twitter activity and uncoordinated activity leading to the 2019 UK General Election (Nizzoli et al. Reference Nizzoli, Tardelli, Avvenuti, Cresci and Tesconi2020), and to characterize the panel of judges’ adjustments to automated email reply suggestions (Robertson et al. Reference Robertson, Olteanu, Diaz, Shokouhi and Bailey2021).

Tweets of every member of the three largest retweet communities were aggregated into three distinct text corpora. Then, the lemmatization tool of the Zemberek library was applied and unigram and bigram frequencies were built for each corpus. Finally, each community’s text corpus was represented as a probability distribution of text units (i.e., unigrams and bigrams) that have at least one animal lemma from previously described composite animal dictionaries. In the results section, the findings of three pairwise community-comparison charts with the top 50 divergent text units are presented.

Results

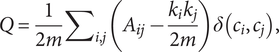

Toward whom is negative animalization directed? The results show that the most frequent target of the negative uses of animalization was PKK (11K tweets). The HDP and Kurdish people in general were also mentioned with considerable frequency (9K tweets). It is estimated that between November 2021 and May 2022, there have been close to 29K negative animalization attributions made to Kurdish people and organizations in Turkish tweets. This phenomenon is discussed in further detail in the following sections. Estimated number of tweets with negative animalization can be found in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Estimated number of tweets with negative animalization.

How Is Negative Animalization Attributed to Groups?

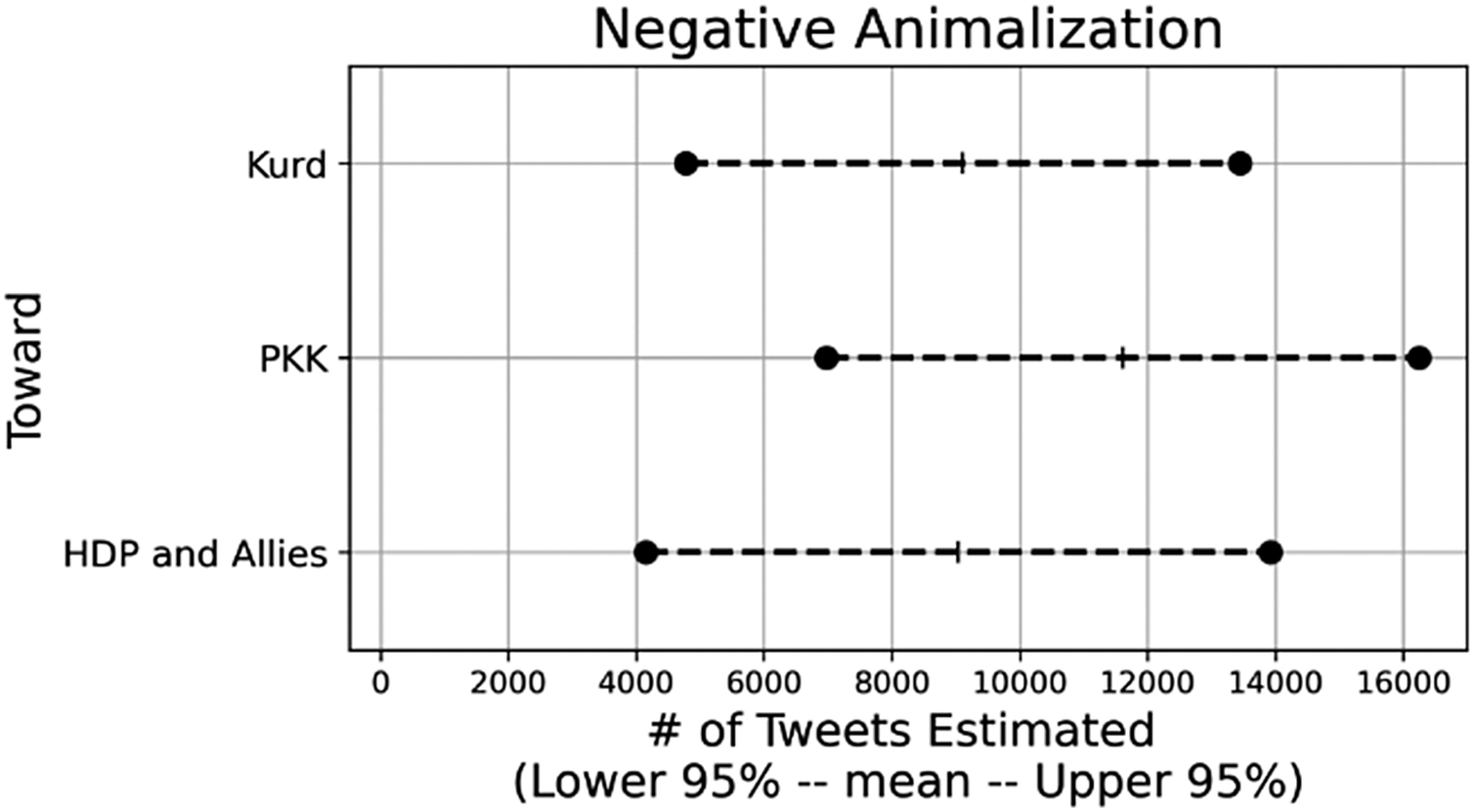

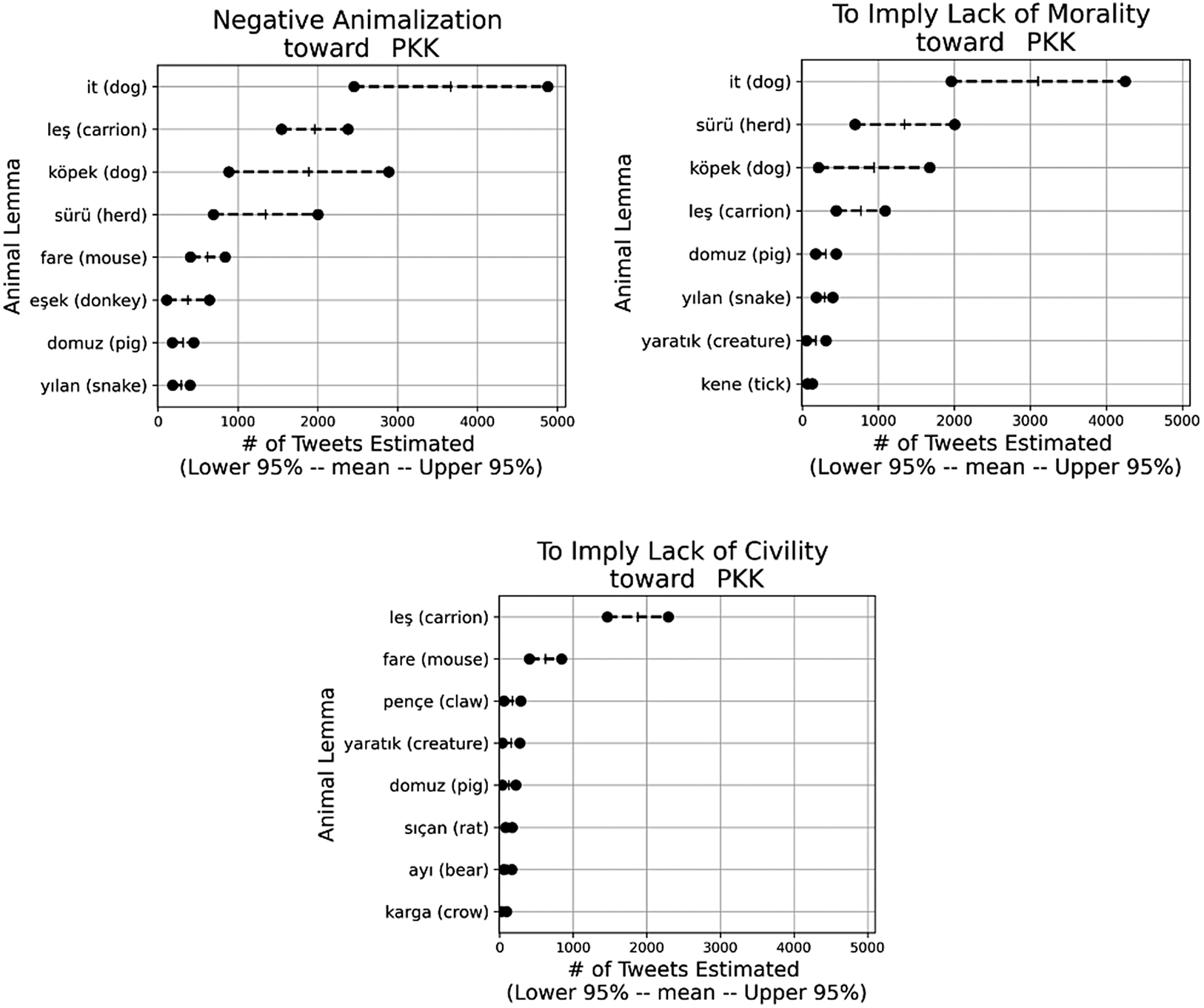

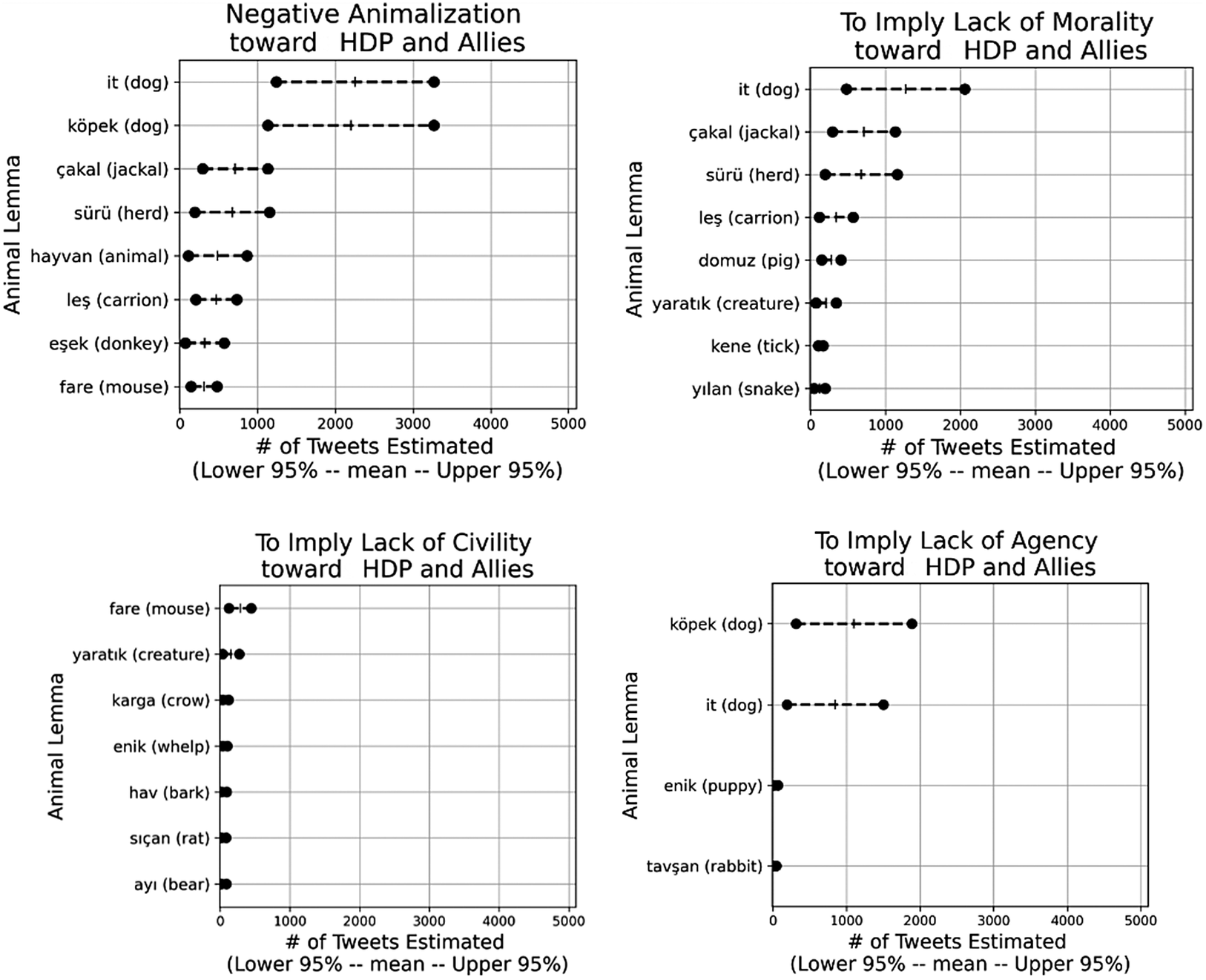

Figure 5 shows the estimated number of animalizing tweets with lack of trait attributions regarding each examined actor. Negative uses of animalistic dehumanization in relation to PKK actors mostly imply lack of morality, followed by lack of civility. This shows that PKK was considered a potent enemy by most users in the data set, not lacking agency or rationality in many cases. However, PKK members were considered, first, despicable and evil and, second, barbaric and wild. Compared with the examples of animalistic dehumanization directed toward Kurds in general or HDP actors, PKK is considered a vile organization, which attributes to them a greater capacity for harmfulness.

Figure 5. Estimated number of animalizing tweets with lack of trait attribution.

Animalizations that attribute lack of civility were common for Kurds as a group. However, similar attributions cannot be considered frequent for actors linked to HDP in the data set. These results can be interpreted as a tendency to denominating Kurds as barbaric and backward people. Thus, the animalizations were mostly used for painting Kurds as uncivil in cases of explicit racialization. Attributions of lack of civility were more common when other political actors were mentioned in the corpus. In the case of HDP actors, attributing lack of agency was the highest appearing animalization strategy. This means that HDP actors were seen not just as lacking morality but also as lacking agency. Attributing a lack of rationality to Kurds as a group in the corpus was relatively common, which also strengthened the stereotype of simple, child-like, and backward Kurdish people. Negative animalizations were common in all three cases, but the specific animals that were used for attributing lack of traits were different.

Attributing lack of agency and morality to the largest (and almost unrivaled) pro-Kurdish legal political party means dismissing the possibility of equal political participation of the Kurds in Turkey. Immorality attributions may result in moral exclusion, defined as perceiving individuals and groups “as outside the boundary in which moral values, rules, and considerations of fairness apply,” thus legitimizing possible harm and exploitation (Opotow Reference Opotow1990, 1). Attributing immoral traits to social actors implies that desired social relationships cannot be established with them (Alexander Reference Alexander2006, 58). Lack of agency attributions also result in discarding the other side by claiming that their actions are determined by other social actors. This allows overlooking the legitimacy of HDP in political processes, which also means overlooking the will of their overwhelmingly pro-Kurdish voters.

Although lack of morality was also frequently attributed to PKK and related actors in the data set, lack-of-civility attributions were more notable than were lack-of-agency attributions. Attributing lack of civility references the long-established dichotomy of “animality/savagery and humanity/civility” (Anderson Reference Anderson2000, 311). Classifying the other as a barbarian that lacks civility allows for legitimizing ethnic domination (Machery Reference Machery and Kronfeldner2021). After all, it has been argued throughout the Western history that the supposedly “savage” people “do not deserve human treatment” (Bar-Tal Reference Bar-Tal1990). The uncivil is considered not worthy of negotiation (Tutkal Reference Tutkal2022), which makes a successful peace process almost impossible.

Finally, lack of civility was also frequently attributed to the Kurdish people in general. Attributing incivility to the Kurds was also documented in other cases, which also results in depicting the Kurdish people as more aggressive and prone to violence (Soleimani and Mohammadpour Reference Soleimani and Mohammadpour2022). This legitimizes the structural racism and unequal relations in countries where Kurds live, which also serves to maintain the status quo by negating the problems.

Sewer Rats, Landmine Donkeys, Traitor Dogs: Dehumanizing Animal References

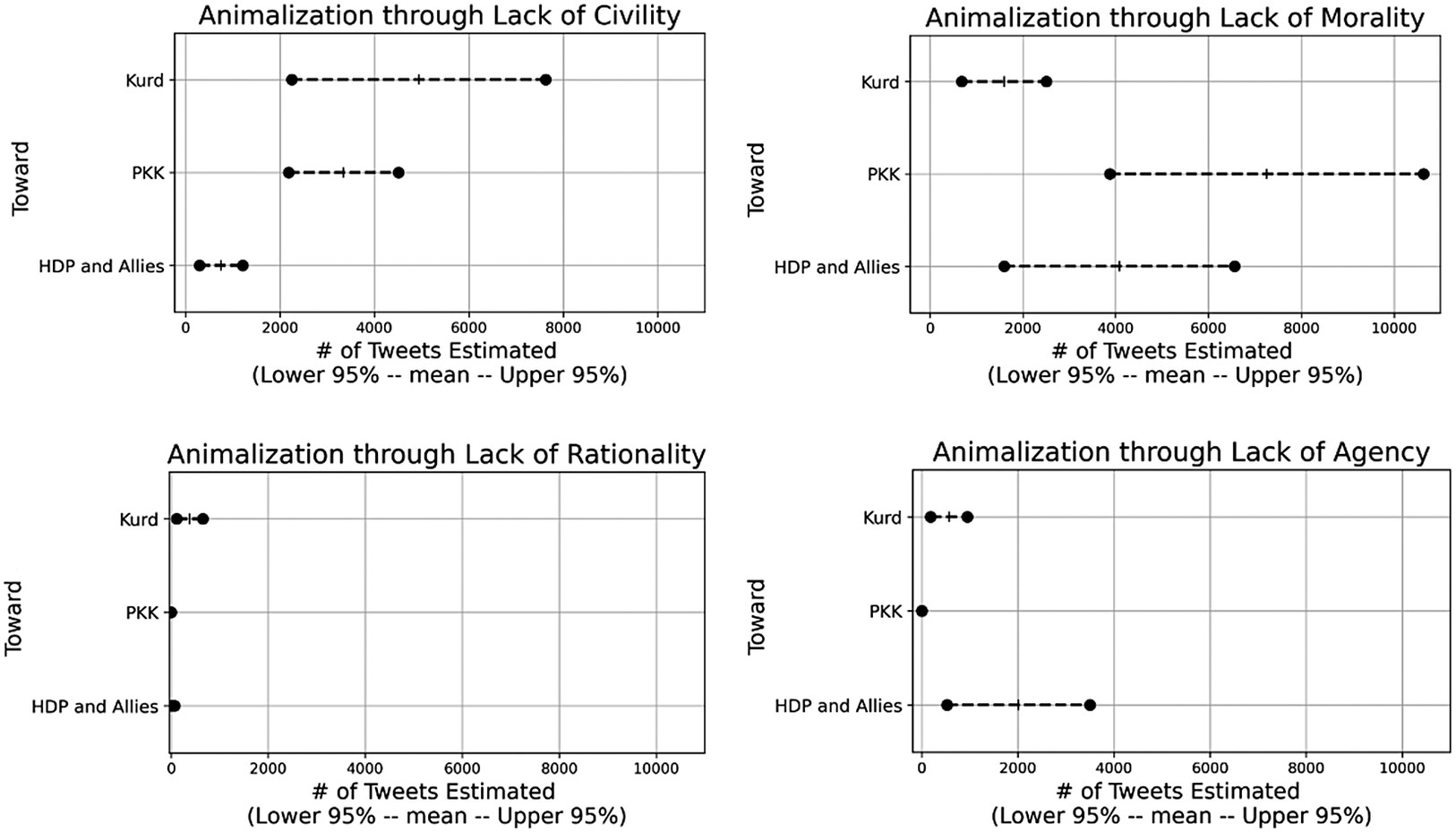

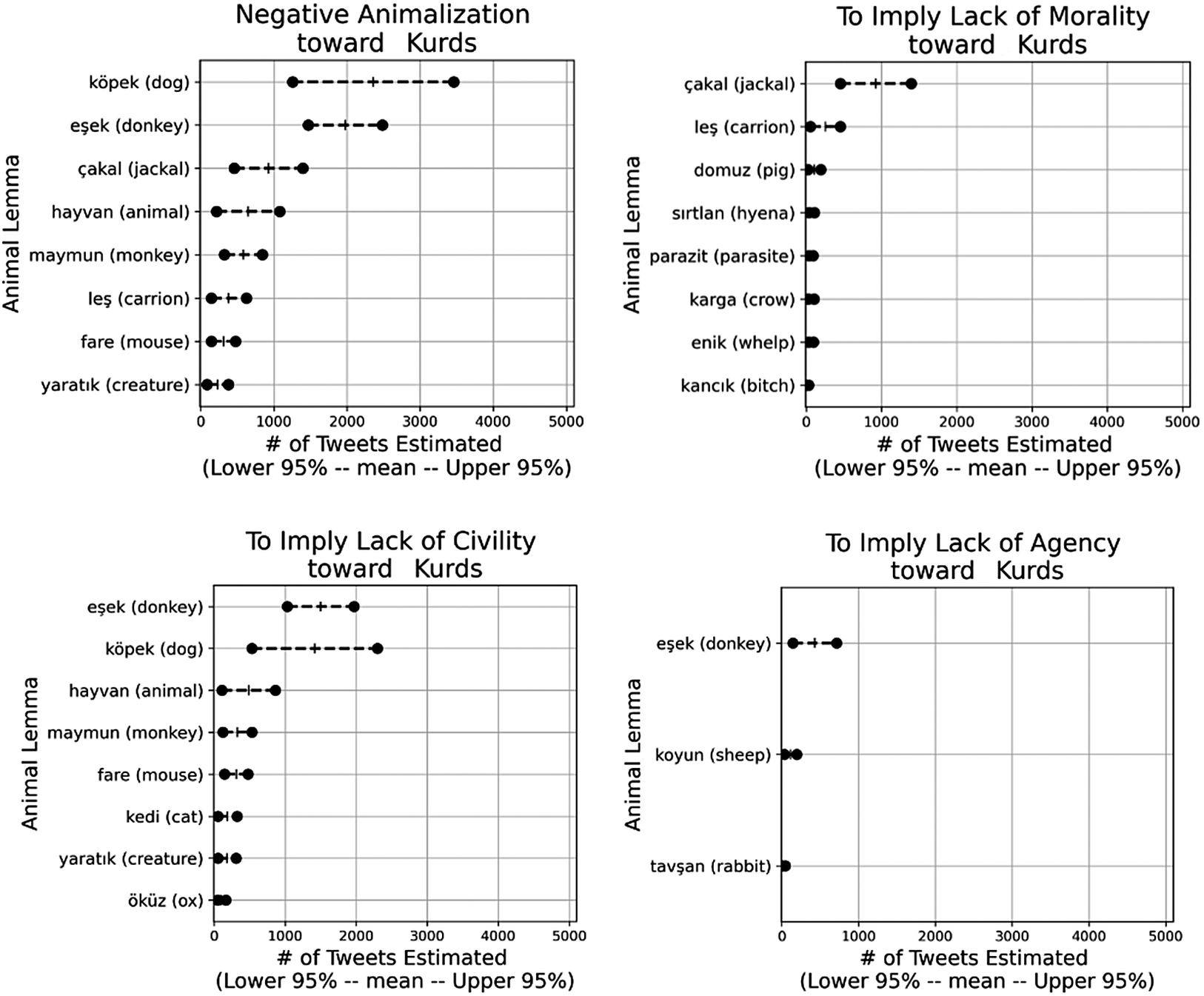

What animal words or animalistic concepts are in action when Twitter users make negative animalization attributions to Kurds and pro-Kurdish organizations? Figure 6 and Figure 7 show the most frequently mentioned animal lemmas targeting Kurds as a whole. They also demonstrate the animal lemmas that are used for attributing different dehumanizing traits.

Figure 6. Estimated number of animalizing tweets with specific animal lemmas.

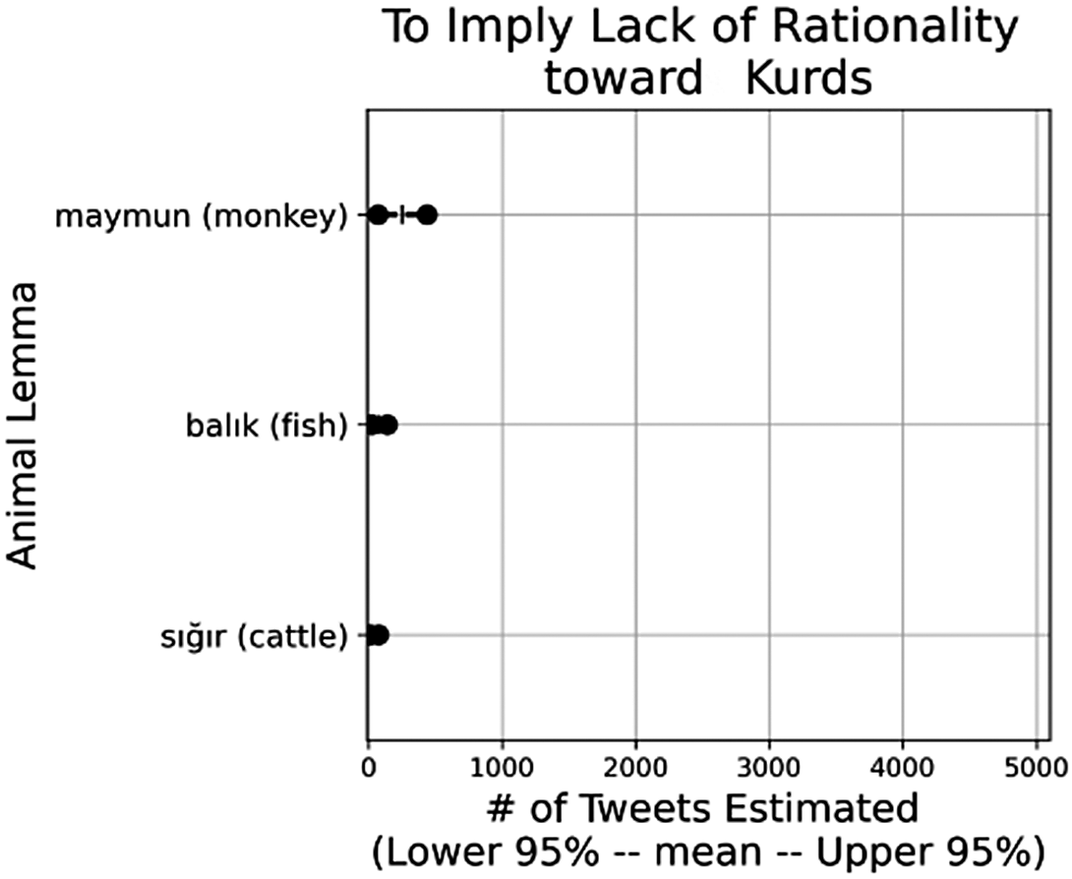

Figure 7. Estimated number of tweets directed toward Kurds implying lack of rationality with specific animal lemmas.

Dogs (köpek) and donkeys (eşek) were the most common references in tweets that contain negative animalizations of Kurds as a group. Dogs were mostly used for implying lack of civility, which may be linked to the fact that the vast majority of Sunni Kurds are from the Shafi’i school in which direct contact with dogs is prohibited except for rare cases. Because dogs are considered “dirty” and “haram,” they have lower status than do most other animals. In this case, lacking cleanness or religious values correlates with lacking civility. Donkey references mostly imply lack of civility and lack of agency. Although in most cases lack of civility was claimed by accusing Kurdish people of bestiality with donkeys, lack of agency was argued by naming Kurds “landmine donkeys” or donkeys of some other actor. References to “landmine donkeys” emphasize lack of agency because these donkeys are used for detecting landmines without causing human casualties. Other frequently used animal metaphors were jackal, animal, monkey, carrion, mouse, and creature. Similar to other scavengers and carrion-eating animals, jackals are associated with lack of moral sensibility and immoral qualities; one such association is with “profiteers” (Andrighetto et al. Reference Andrighetto, Riva, Gabbiadini and Volpato2016, 634). Direct references to “animals” as a general category were mostly used to imply lack of civility. Monkey references directed at Kurds were mostly used for claiming lack of civility and rationality. These references derive from considering monkeys as subhumans that did not develop cognitive skills and abilities that allow for reaching a civilized condition. The most frequent use of carrion references, in this case, was attributing lack of moral sensibility by using the word “carrion” (leş) as an adjective. Mouse references were overwhelmingly used for underlining lack of civility by calling Kurds “mountain rats,” “sewer rats,” “Zagros rats,” or “Mesopotamian rats.” Even though there is a separate word for “rat” in Turkish, which was also included in this research (sıçan), most users preferred using the word for mouse (fare) instead of the word for rat. Although references to sewer rats are disgust-eliciting and imply being dirty, those to mountain or Zagros rats imply lacking civility for being based on mountains and far away from urban centers. Because Zagros is a long mountain range in Kurdistan, its use may be considered mostly interchangeable with mountain rats. Mesopotamian rats imply being from the East, which is considered less civilized than the “West” from an orientalist gaze. Finally, “creature” references were mostly used for implying lack of civility or morality. When “creature” was used for denominating an animal-like or even-lower-than-animal status, it usually claimed lack of civility; when it was used in a similar way to “monster,” it usually claimed lack of morality.

Figure 8 shows the most frequently mentioned animal lemmas targeting PKK and animal lemmas that were used to attribute lack of morality and lack of civility toward them. İt (both it and köpek mean dog in Turkish; however, it always has negative connotations, but köpek can also be used in positive or neutral ways) references were the most common among negative animalization of actors from the PKK, whereas the other word for dog (köpek) was the third. In the case of PKK, it was mostly used for attributing lack of morality even though it may also imply lack of civility, or agency. In a similar way, köpek was mostly used for implying lack of morality or civility even though in other cases it may also imply lack of agency or rationality.

Figure 8. Estimated number of animalizing tweets directed toward PKK with specific animal lemmas.

Carrion references were the second most common among negative animalizations of actors from the PKK. By implying lack of cleanliness and being unworthy of respect, many carrion references can be linked to lack of civility, even though in some cases carrion (leş) as an adjective is also used for attributing lack of morality. Other most-frequently used animal references in relation to PKK actors were sürü (which stands for herd, flock, and pack at the same time), mouse, donkey, pig, and snake. The connotations of sürü references mostly depend on the accompanying words. In the case of PKK, these references mostly imply lack of morality due to accompanying words such as murderers, dogs, jackals, or traitors. Mouse references directed at PKK actors almost always implied lack of civility by attributing lack of cleanliness or being from rural or mountainous regions. Donkey references were most common in tweets that imply lack of agency, especially by calling PKK actors landmine donkeys. Pig and snake references were mostly used for implying lack of morality. Pig references were used for attributing immorality because pigs are associated with a variety of negative qualities in Muslim societies in relation to the prevailing pig taboo in Islam. In Turkey, pigs are considered greedy and unethical; there are urban legends about pigs not being “jealous” (which is considered a positive quality among the conservative sections of Turkey) and people that eat pork “being unconcerned about their mates’ infidelities” (Mandel Reference Mandel1989, 40). Snake references are usually used to attribute a treacherous, evil, and threatening nature.

Figure 9 and Figure 10 show the most frequently mentioned animal lemmas targeting HDP and account for the animal lemmas used for attributing different dehumanizing traits. In the case of HDP and related actors, most negative animalizations were done via the use of references to dogs (both it and köpek). Other frequent animalizing references were made through the words jackal, herd/pack (sürü), animal, carrion, donkey, and mouse. İt was mostly used for claiming lack of civility or lack of agency, whereas köpek was mostly used for implying lack of agency by accusing HDP or related actors of being dogs of some other actor such as PKK, Armenian people, Jewish people, “imperialists,” or the Western states. Jackal references were almost always used for claiming lack of morality, whereas sürü references mostly implied lack of morality because they were accompanied by words such as it or “murderer.” Direct references to the word “animal” were mostly used to argue for lack of civility, especially by claiming that actors related to HDP were even “inferior” to animals. Carrion references were mostly used to attribute lack of morality by using the word “carrion” as a negative adjective, similar to its use in the carrion references in relation to Kurds as a whole. Although most donkey references were used for claiming lack of agency, especially by the use of the term “landmine donkeys,” mouse references were used for attributing lack of civility, especially by calling the actors sewer rats or mountain rats.

Figure 9. Estimated number of animalizing tweets directed toward HDP with specific animal lemmas.

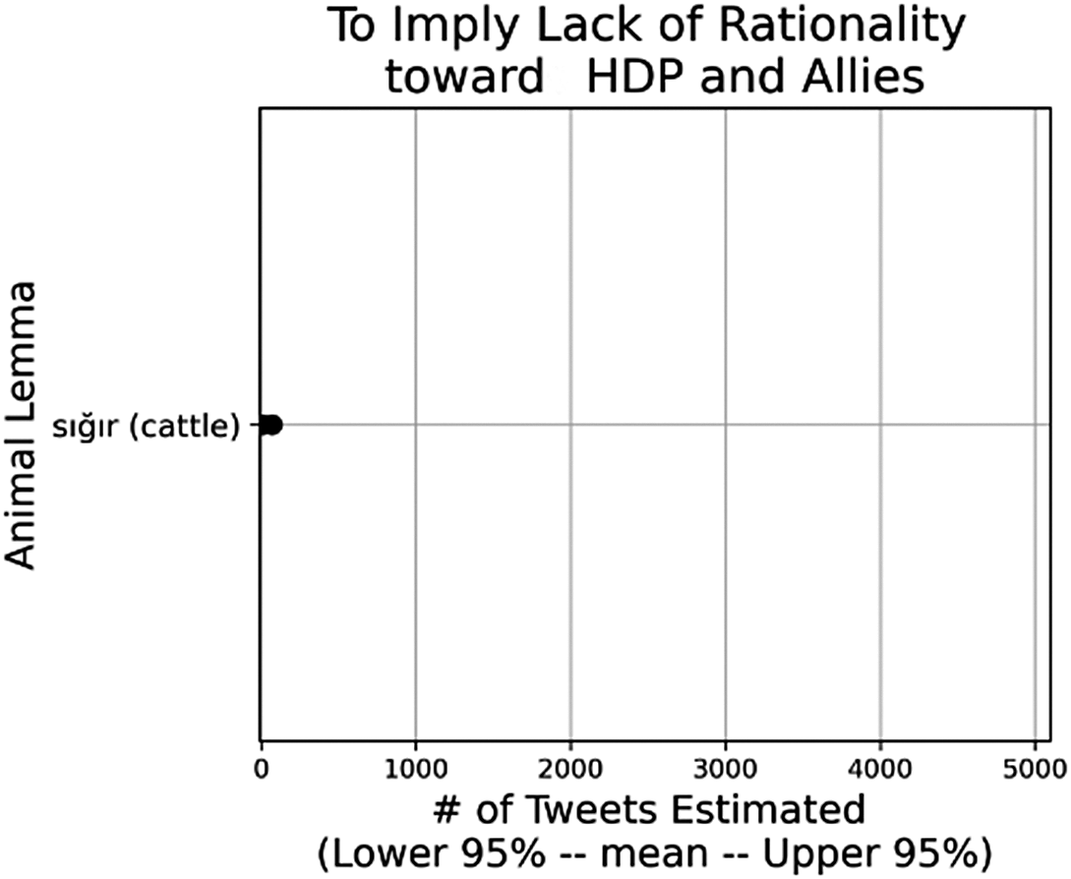

Figure 10. Estimated number of tweets directed at HDP implying a lack of rationality with specific animal lemmas.

The findings reveal that jackal, dog (it), carrion, herd/pack (sürü), and pig references were frequently made for attributing lack of moral sensibility. Jackal references, which imply profiteering, self-seeking, and cowardness, were frequently used for Kurds and HDP actors but not for PKK actors. This can be interpreted as the attribution of a “potent-enemy” status to PKK when Kurds are explicitly mentioned. It is also interesting that dogs were not used to attribute lack of moral sensibility to Kurds. Donkey, dog, animal, and monkey references were frequently made to attribute lack of civility to Kurds as a group. Here, most donkey references were used for accusing Kurdish people (mostly men) of bestiality with these animals. Carrion and mouse references were most frequently directed at the PKK when attributing lack of civility, whereas for HDP actors the most frequent references were to mice and creatures. Finally, lack of agency and lack of rationality were not commonly attributed to PKK actors. These attributions were made to Kurds via donkey and sheep references, whereas dog references were directed at HDP actors for the same reason. This means that the Kurds were accused of being donkeys of other actors or blindly following sheep. In the corpus, HDP actors were accused of being dogs of other actors, which implies a more aggressive status. Monkey and fish references were the most common for attributing lack of rationality to Kurds, whereas for HDP members and allies this was mostly done by using cattle references.

Measuring an Authentic User Activity

How would negative animalization tweets’ diffusion compare with a random tweet about Kurds? Is the prevalence of negative animalization tweets attributable to more than normal retweeting activity? Is there a coordinated effort behind such tweets? To make sure the findings are not a by-product of synthetic activity, three analyses were conducted:

-

• Compare retweet counts of negative animalization tweets with random tweet samples (equal sample size to negative animalization tweets).

-

• Compare unique user count of negative animalization tweets with random tweet samples.

-

• Compare textual diversity (copy/paste efforts) of negative animalization tweets with random tweet samples.

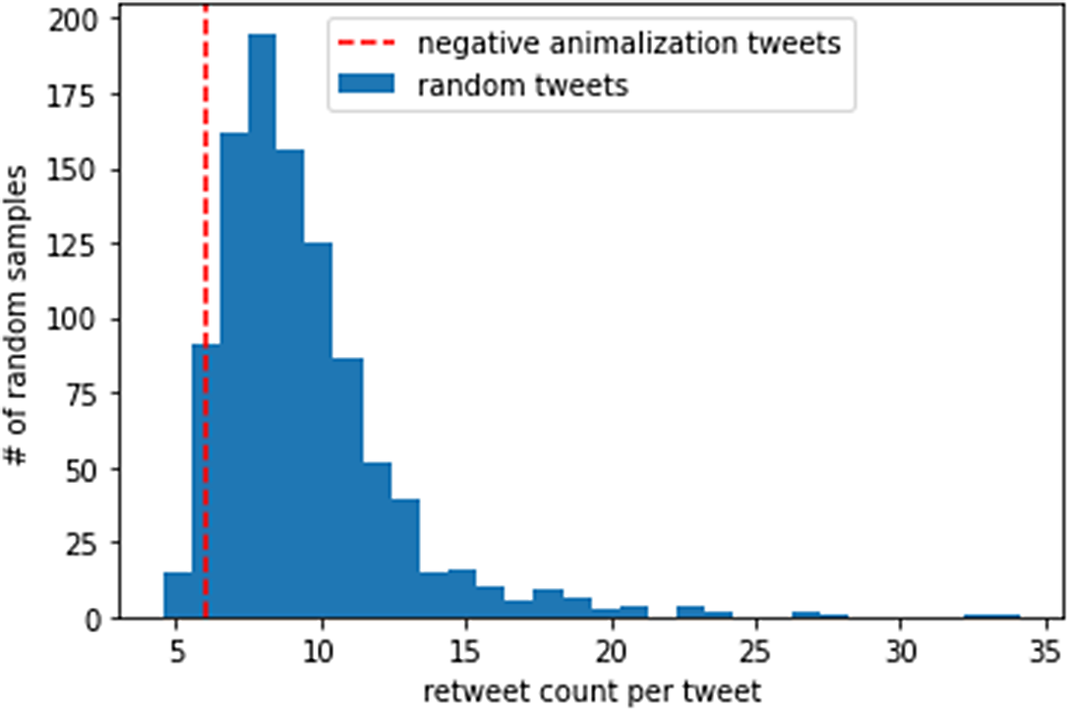

First, the average number of retweets that negative animalization tweets (N = 722) received was calculated. The results indicate that a negative animalization tweet receives an average of 6.0121 retweets. Then, 1,000 random samples (N = 722) from the full original (not retweet) tweet data set were taken and the average number of retweets these randomly sampled tweets received was calculated. The average number of retweets for the 1,000 random samples was 9.4260. The full distribution for the 1,000 random samples was plotted below alongside the average for negative animalization tweets, shown as a vertical line. Comparison of retweet count per tweet between negative animalization tweets and random tweets can be seen in Figure 11.

Figure 11. Comparison of retweet count per tweet for negative animalization tweets and random tweets.

Only 40 of the 1,000 (0.04) random samples have a lower average number of retweets than negative animalization tweets, which establishes strong evidence that negative animalization tweets are not part of greater-than-normal retweeting activity.

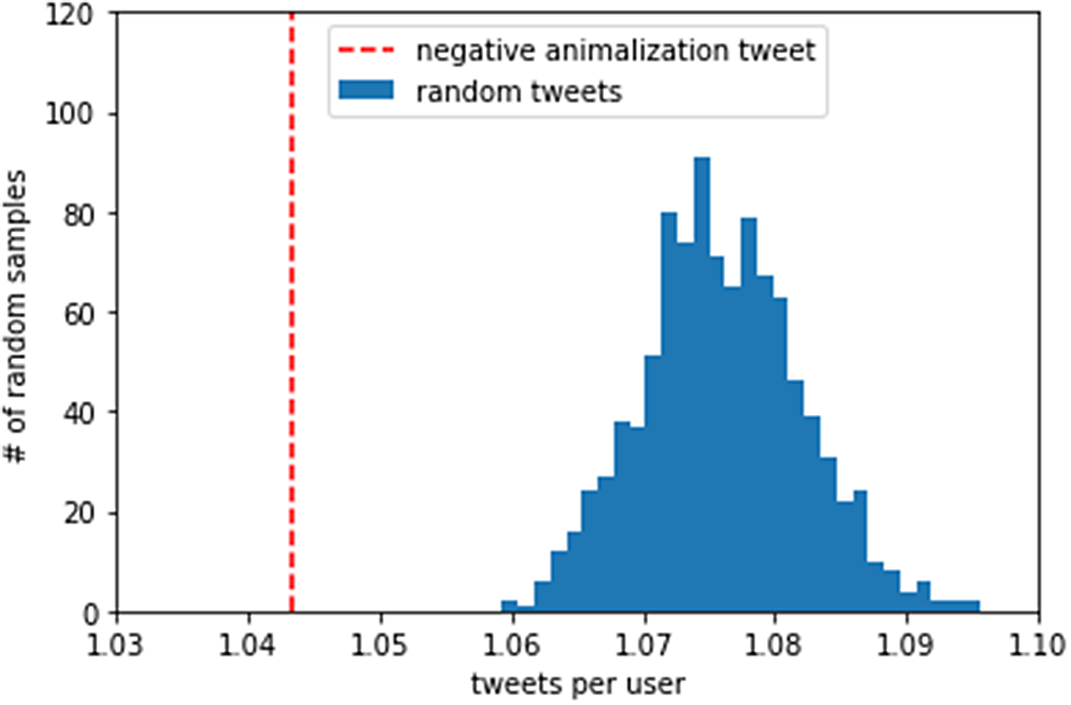

Second, tweet per account rate was calculated. The results indicated that users who posted negative animalization tweets posted an average of 1.0434 negative animalization tweets. Then, 1,000 random samples (N = 722) were taken from the full original (not retweet) tweet data set and tweet per account rate of accounts that these randomly sampled tweets are posted from was calculated. The average of 1,000 random samples was 1.0759. The full distribution of 1,000 random samples was plotted as shown below alongside the average for negative animalization tweets, shown as a vertical line. Comparison of tweets count per user between negative animalization tweets and random tweets can be seen in Figure 12.

Figure 12. Comparison of tweets count per user for negative animalization tweets and random tweets.

None of 1,000 random samples has lower average tweet per account rate than negative animalization tweeters. This establishes strong evidence that negative animalization tweeters are not part of ultra-active users.

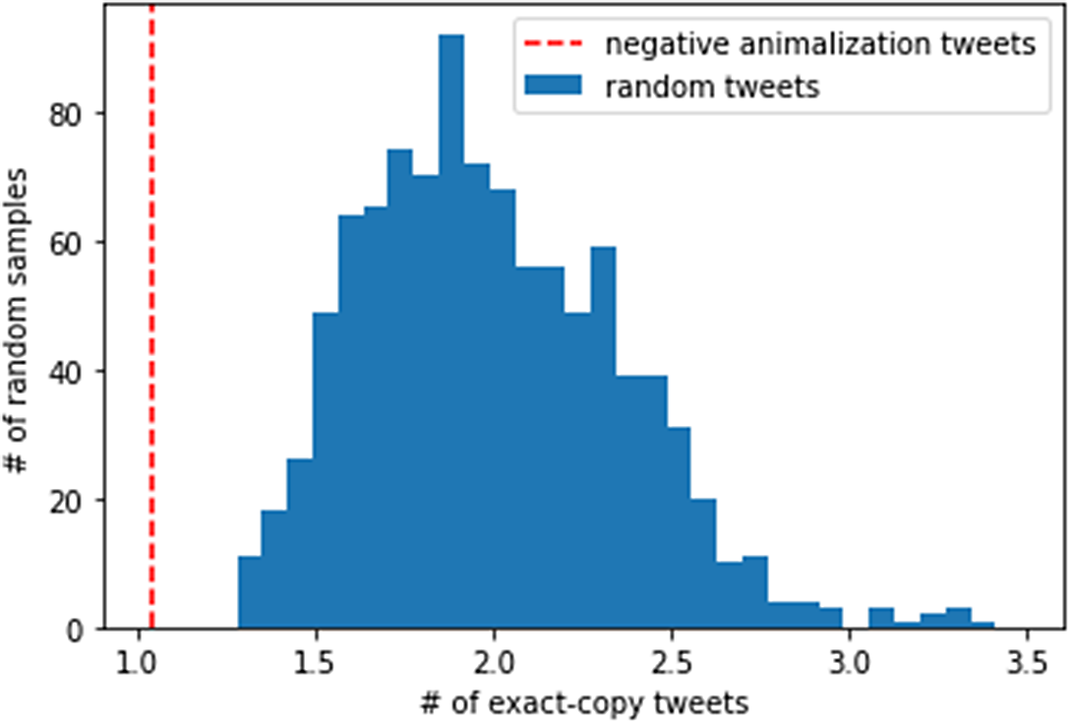

Third, the average number of exact-copy tweets per negative animalization tweet was calculated. On average, there are 1.0376 exact-copy tweets per negative animalization tweet. Then, 1,000 random samples (N = 722) were taken from the full original (not retweet) tweet data set and average number of copycat tweets per each tweet sample was calculated. The average of 1,000 random samples was 1.9918. The full distribution of 1,000 random samples is plotted as shown below in Figure 13, with the negative animalization tweets’ average copycat count shown as a vertical line. Comparison of the number of exact copy tweets between negative animalization tweets and random tweets can also be seen in Figure 13.

Figure 13. Comparison of the number of exact copy tweets for negative animalization tweets and random tweets.

None of the 1,000 random samples has a lower average for copycat tweets than the negative animalization tweets’ average copycat count. This establishes strong evidence that negative animalization tweets do not originate from a more coordinated copy/paste tweeting activity than the general conversation about Kurds on Twitter.

These three separate analyses demonstrate that negative animalization tweets that are directed at Kurds, HDP and allies, and PKK are not the result of an abnormal retweeting activity or a coordinated ultra-active user effort.

Who Are the Attributors and How Do They Differ in Their Animalization Vocabulary?

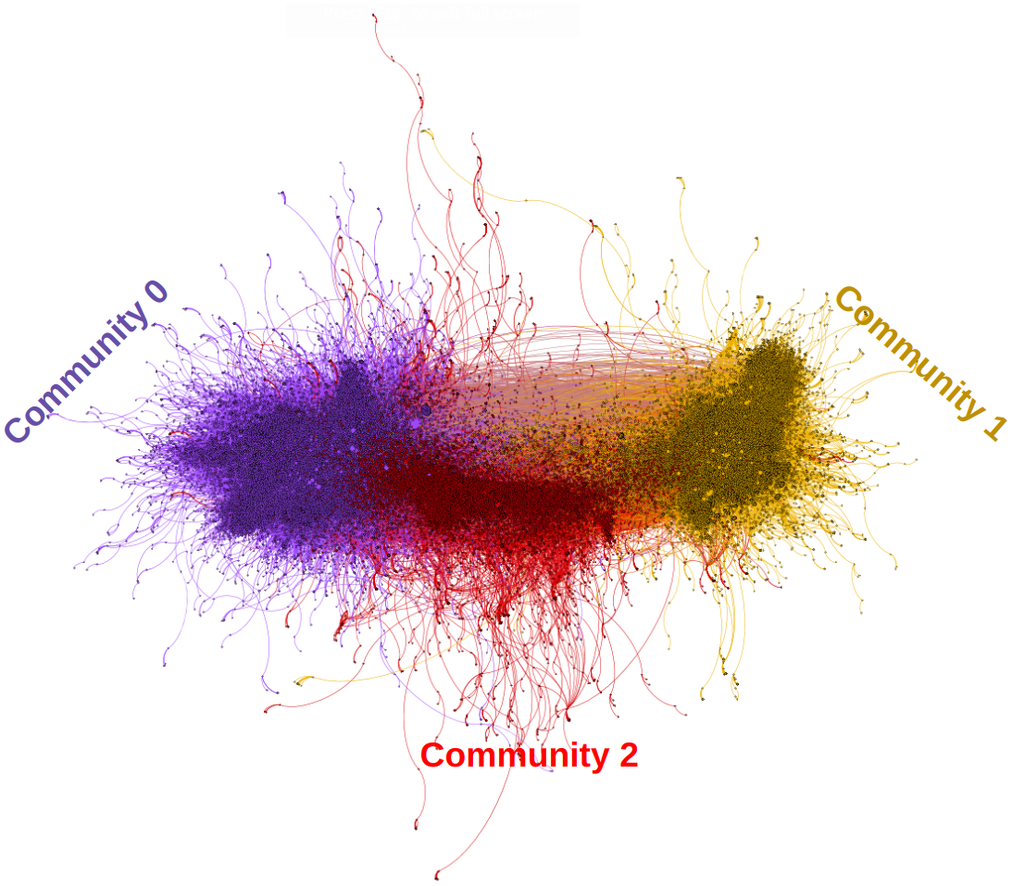

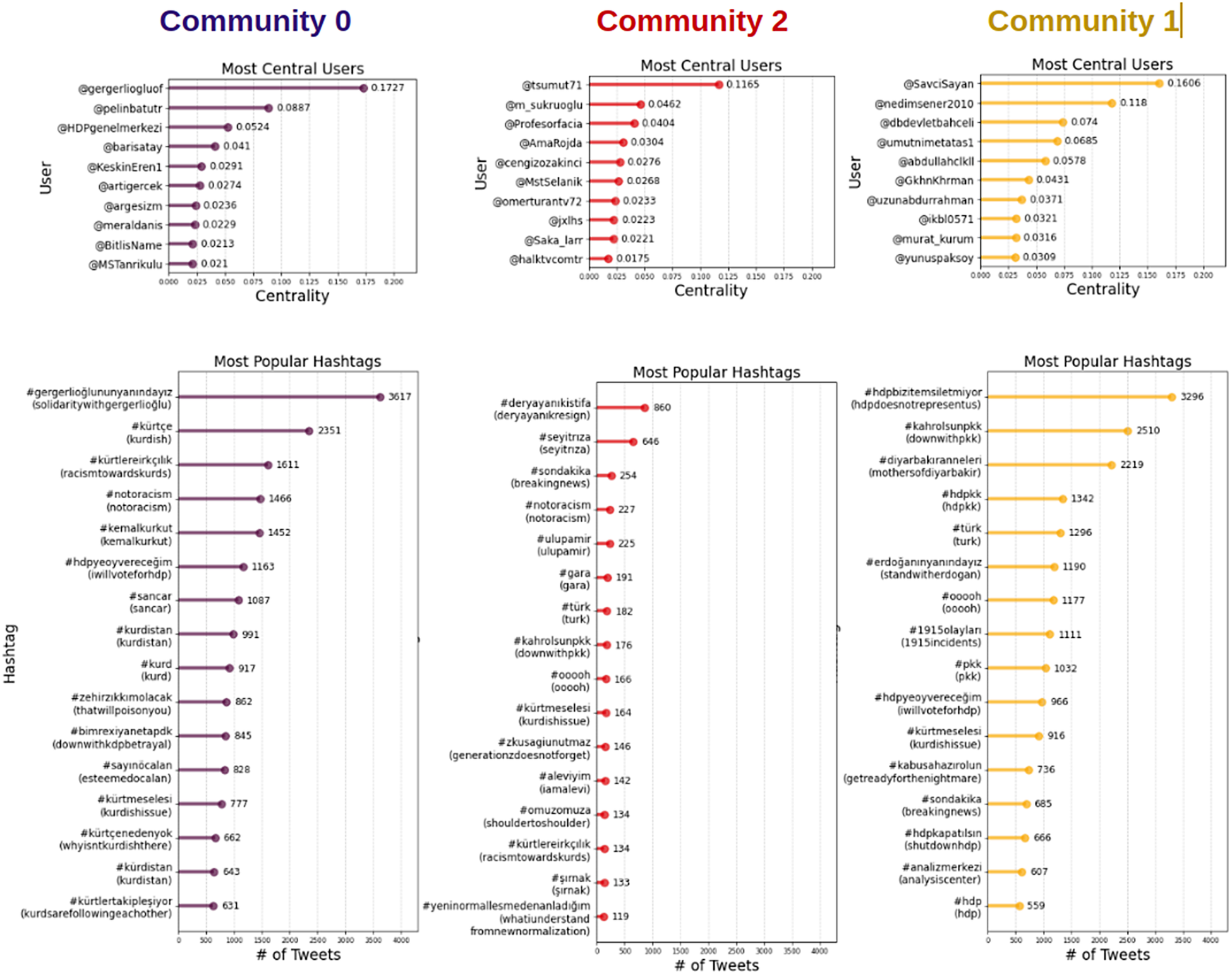

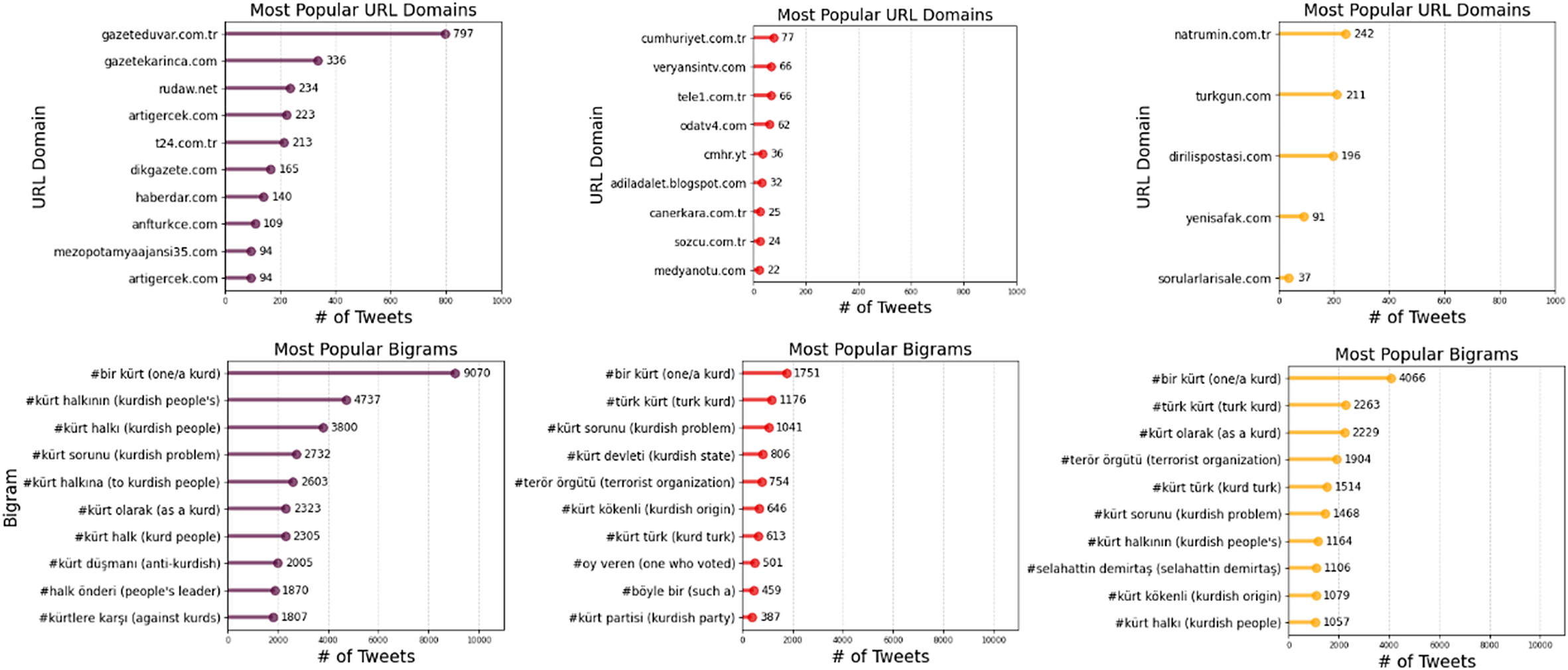

Figure 14 shows the retweet network layout of political communities generated by the Gephi force atlas 2 algorithm, and Figures 15 and 16 summarize the most popular hashtags, users, bigrams, and URLs for the top three communities.

Figure 14. Retweet network layout of political communities generated by Gephi’s force atlas 2 algorithm.

Figure 15. Most central users and most popular hashtags for the communities.

Figure 16. Most popular URL domains and most popular bigrams for the communities

Members of Community 0 usually retweet entries from HDP Members of Parliament (MPs) or MPs from its ally, TİP (Türkiye İşçi Partisi or Workers’ Party of Turkey). They also retweet entries from human rights defenders and public intellectuals who are sympathetic toward pro-Kurdish demands. Members of Community 1 tend to retweet entries from mayors and MPs from AKP (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi or Justice and Development Party) as well as entries from President Erdoğan and other high-ranked AKP officials. Finally, members of Community 2 tend to retweet entries from nationalist public intellectuals that oppose the current government. They also retweet entries from CHP (Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi or Republican People’s Party) and İYİ Parti (Good Party) MPs.

Legal political actors in Turkey divide among (1) the alliance of Islamists and conservative nationalists, (2) the alliance of secular and/or social-democratic nationalists and right-wing political actors that are excluded from the government, and (3) the alliance of the Kurdish political movement with minority political groups and most Turkish socialists. The largest three communities in this research also mostly correspond to this division.

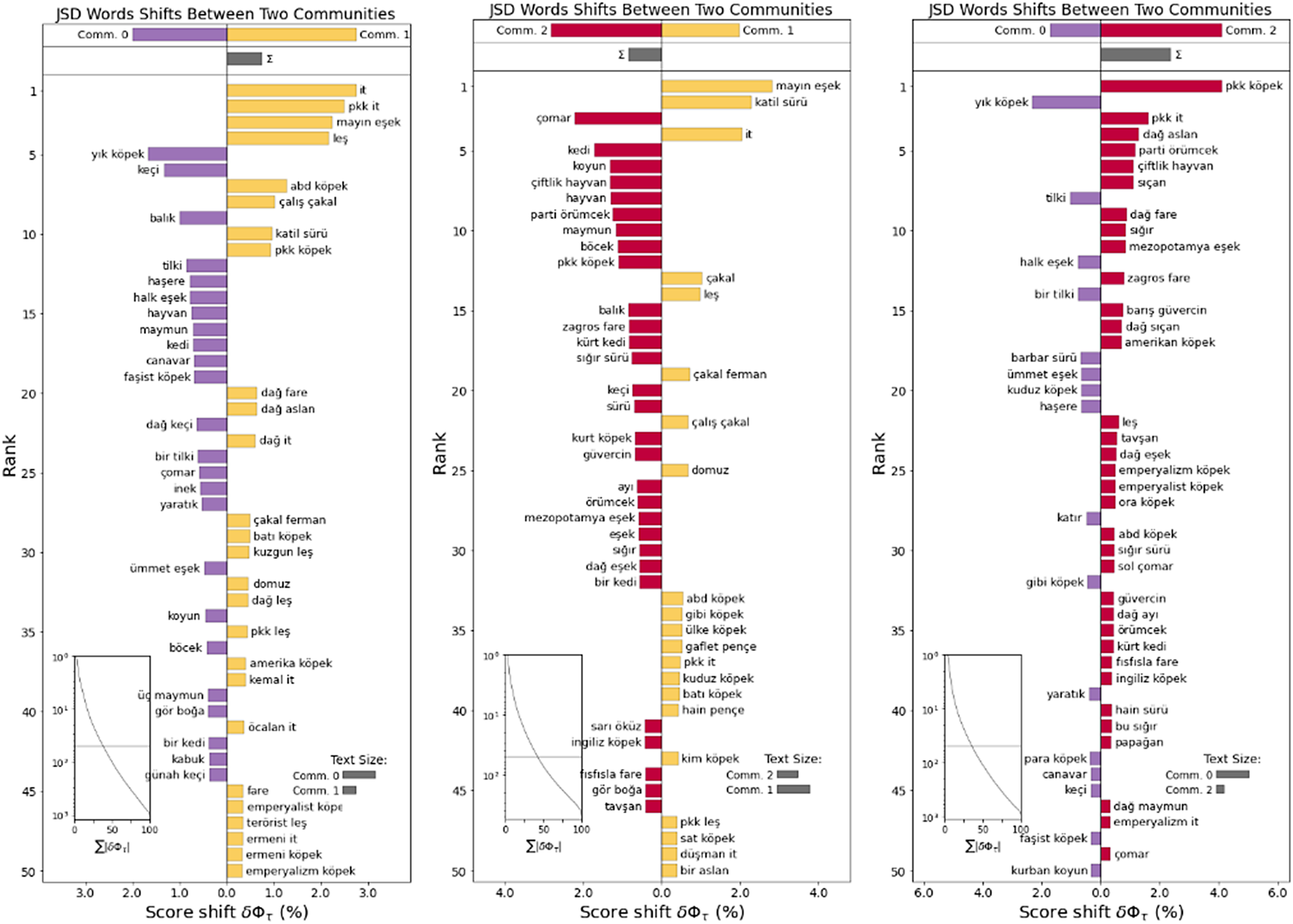

The word shifts tables in Figure 17 show that members of Community 1 more frequently used the words it and carrion (leş) compared with members of Community 0. Landmine donkey was also a frequent reference. The pair of “order” and jackal was mostly used to say that orders of jackals were to be slashed by the “grey wolves,” a direct reference to the paramilitary group with the same name and the associated political party, MHP (Milliyetçi Hareket Partisi or Nationalist Action Party). Thus, jackal was used to signify a lower status even among the animals. There were many references to dogs and the United States together, which usually happens when actors are accused of being dogs of the United States. Dogs were also frequently used by members of Community 0. Although dog references from Community 0 mostly imply lack of morality—for example, by calling adversaries “fascist dogs” or “racist dogs”—dog references from Community 1 imply lack of agency in addition to claims of lack of morality. These implications of lack of agency are usually made by claiming that actors are dogs of different actors such as the USA, PKK, or the West. Goat and fish references were also common in entries from Community 0. Goat references are mostly used in a positive way, especially in self-definition because goats are associated with stubbornness in Turkey. Negative uses of goat references are usually accusations of bestiality, which is extremely rare among members of Community 0 compared with others. Fish are mostly used for claiming lack of rationality, especially by underlining lack of mnemonic abilities.

Figure 17. JSD words shifts between communities.

The shift was greater for references to landmine donkeys, murderer packs, and dogs (it) from Community 1 to Community 2, followed by jackal and carrion references. These are mostly used for underlining lack of morality, except for “landmine donkey” references that are used for claiming lack of agency. The word that was overwhelmingly used by more members of Community 2 than of Community 1 is çomar, which is a shepherd dog common in the central parts of Turkey. The word is used as an insult that is directed at people from rural and conservative parts of the country, especially the voters of AKP, and it implies lack of civility. Other animal references more common in Community 2 than in Community 1 include cats, sheep, farm animals, spiders, monkeys, and bugs. References to sheep and farm animals usually imply lack of agency, whereas spiders, monkeys, and bugs mostly denominate lack of civility. Here, it must be noted that being “spider-headed” or “spider-brained” usually means being overly conservative or religious in Turkish; thus, it is a direct reference to Islamists. Cats can be used for underlining lack of morality, especially in relation to Turkish sayings such as “transforming into a cat” in front of someone, which implies cowardice or playing with someone like how a cat plays with mice, which implies malice and cruelty.

Concerning word shifts in Twitter entries between Community 2 and Community 0, members of Community 2 more frequently use dog references in relation to PKK. They also use lions; however, this was used mostly in a positive way, especially to denominate Turkish soldiers. Other more frequent animal references from Community 2 than from Community 0 were spiders, farm animals, and rats. As was stated, members of Community 0 also used dog references. Finally, fox references are also relatively common for members of Community 0, claiming lack of morality by attributing slyness and insincerity.

Government-supporting Islamists and conservative nationalists heavily used words or word pairs that imply either lack of agency (e.g., “landmine–donkey” or “the USA–dog”) or lack of morality (e.g., “carrion,” “murderer–pack,” etc.) compared with both opposition groups (secular nationalists and pro-Kurdish groups). For secular nationalist or social-democratic opposition supporters, they prefer to place more emphasis on lack of civility (e.g., “çomar,” “party–spider,” monkey,” etc.) and lack of agency (e.g., “sheep,” “farm–animal,” “PKK–dog,” etc.) compared with government supporters. When the comparison is made with pro-Kurdish Twitter users, these references also existed but were now joined by disgust-eliciting metaphors such as rat or more words attributing a lack of agency, such as cattle. Pro-Kurdish users usually focused on attributing lack of morality to the members of the other two communities, especially by mentioning dogs.

Discussion

This work documents various user groups’ narrative strategies in their negative animalization attributions to Kurds and pro-Kurdish organizations. Animalizing discourses reproduce the systemic racism in Turkey and make future attempts of peacebuilding and reconciliation difficult. Racism, understood as “a system of ethnic or racial domination” (van Dijk Reference van Dijk2021), is considered a structure in this research. It is also accepted that the discourse plays an important role in reproducing and legitimizing this structural racism. After all, it is mainly through discourse that ethnic prejudice is acquired and ethnic discrimination is both enacted and legitimized (van Dijk Reference van Dijk2021). Discourse is only one of many forms of racist practice, but it is crucial in “the societal reproduction of the basic mechanisms of most other racist practices” (van Dijk Reference van Dijk1993, 13). Animalizing the Kurds also results in racialization, which is a strategy that has been used many times in different contexts as “a source of cultural integrity, political leverage, and economic gain for those imperial and white settler groups armed with the power of definition” (Anderson Reference Anderson2000, 303).

Another important implication of animalization can be seen in the issue of language as the supposed difference between the human and animal. Language has been considered “the identifying characteristic of the human” (Agamben Reference Agamben2003, 34). In this sense, animalizing the other is also attributing lack of language. If Agamben is right in that “what distinguishes man from animal is language” (2003, 36), the animalization implies the impossibility of establishing dialogue with the other that leads to negotiations and peace. If the other is considered animal, then by the most accepted definition of animal (which is also a historical production as Agamben notes), the other does not possess the language. As a result, to achieve peaceful resolution during a conflict, one of the first steps should be to rehumanize or deanimalize the other. The best way to achieve that may be transcending the dichotomy of human–animal to eradicate the prevailing forms of social hierarchy such as racism and sexism, considering that “constructs of human-animal difference appear also to have been a departure point for ancient conceptions of social hierarchy” (Anderson Reference Anderson2000, 307).

An especially important finding of this research is the seemingly public image of the armed PKK as possessing more agency than the civil HDP. It can be hypothesized that PKK is considered more “authentic” than HDP even by many people that consider PKK an enemy. Here, authenticity means the presentation of actions and opinions as sincere and without ulterior motives. Further research is required here to examine whether animalized “enemy combatants” are considered more authentic than are animalized civilian actors due to an association of the animal with violence, which may result in naturalizing the attacks of the animalized other but considering it suspicious when the other promotes negotiations and dialogue.

Finally, the results should be placed in the context of the animalization of the other in the region. The Turkish–Kurdish conflict has involved the animalization of Kurdish people since its beginning. Kurdish people were considered uncivil, barbarian, and backward by many prominent Turkish public figures; they were also considered irrational zealots. Massacres following the Kurdish rebellions during the early years of the Turkish Republic were considered “civilizing operations” (Özsoy Reference Özsoy, İflazoğlu and Demir2016; Ünlü Reference Ünlü2018). Since then, popular culture has reproduced the idea of “uncivilized Kurds” compared with the “civilizatory Turks” (Ergin Reference Ergin2014; Nas Reference Nas2018). The animalization of Kurds on Turkish-speaking social media is a part of this historic dichotomy, serving to reproduce the structural racism and related social hierarchies in Turkey.

The data imply that, although lack of morality is attributed to all actors (armed PKK, legal and unarmed HDP, and Kurdish people as a whole), this attribution is larger when the armed PKK is the target. We report the trend of attributing lack of agency to HDP more frequently than to other actors, and Kurdish people in general are considered less rational and civilized. This may mean that in ethnic conflicts greater immorality is attributed to the armed organizations, whereas the unarmed political representatives are accused of not having agency and the supported civilian population is considered uncivil, irrational, and generally backward. If further research on dehumanizing discourses during ethnic conflicts supports these implications, it would be possible to mention a general trend in attributions of a lack of human qualities to different otherized actors in ethnic conflicts (e.g., Israeli–Palestinian conflict, Russo–Ukrainian war, Tigray war, Western Sahara conflict, etc.). It would also be interesting to examine discourses of animalizing dehumanization in countries where there is structural racism and/or ethnic polarization but not an ongoing armed conflict (e.g., the United States, Brazil, France, Chile, etc.) to see how these dynamics change and if greater immorality is attributed to more radical political representatives and if lesser agency is attributed to more moderate political representatives. This would be an intriguing area for further research.

Conclusions

This study examined the cases of negative animalizing dehumanization directed at Kurds and Kurdish organizations in Turkish-speaking Twitter when Kurds are explicitly mentioned. The results showed that animalizing tweets attempted to attribute lack of one or more human traits to Kurdish people: agency, civility, morality, and rationality. Thanks to the large data set, it was possible to rank order the prevalence of dehumanization dimensions. The findings show that (1) lack of morality was the largest attribution, whereas (2) lack of civility was the second largest, (3) lack of agency was the third largest, and (4) lack of rationality was the least-mentioned dimension. Lack of civility and rationality were mostly attributed to Kurdish people, whereas lack of morality was attributed to PKK actors and lack of agency was attributed to HDP actors. Lack of agency was rarely attributed to PKK actors, but it was relatively common for HDP and Kurds in general. Although lack of agency, civility, morality, and rationality attributions work in different ways, they all function in a way that makes establishing dialogue and constructing a culture of peace extremely difficult. It is possible to work on future cases to see whether similar attributions are made in other contexts, especially when there is an ongoing ethnic conflict.

Different animal references were used to attribute similar traits to different actors. This allows researchers gain some insight into the role of animalization in political communication in Turkey. By establishing three main political communities among the users, it was also possible to examine the animal references that were more frequently used by members of different communities in tweets when Kurds were explicitly mentioned. Even though this study has certain limitations because it is based on tweets about Kurds and thus cannot make generalizations about the use of animalizing dehumanization in reference to other issues or actors that are mostly silent about the Turkish–Kurdish conflict, it is still plausible to argue that it will be fundamental for future research on animalizing political discourses in Turkey, especially in relation to racialization and ethnic conflicts. The study is also limited to tweets from November 8, 2020, to May 31, 2021, which means that the results are affected by the sociopolitical events of the same period. It is possible to examine similar data sets from different dates to make a comparison and account for the changes over time. This would also allow us to deepen the research findings about the ways in which social media platforms “contribute to racist dynamics” (Matamoros-Fernández Reference Matamoros-Fernández2017).

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/nps.2023.32.

Acknowledgments

I want to express my sincere thanks to a colleague friend who wishes to maintain their anonymity. Their technical contributions were invaluable, and their assistance in data collection and analysis significantly improved the quality of this research.

Disclosure

None.