My major contribution is that I modernized and professionalized ewì. In other words, I raised it from mere mendicancy to professionalism. Nobody can be identified in Yoruba history as having achieved that feat.

(Adepọju 2006: 14)Ewì, a modern genre of Yoruba poetry that freely draws on the vast repertoire of traditional oral literary forms and inhabits the intersection between the written and the oral, is gaining ascendancy within the urban space. Ewì resulted from the impact of literacy and missionary education on Yoruba poetry and remains an enduring testimony to the capacity of the culture to renew itself.Footnote 1 Even though contemporary recognition of the genre dates from the 1960s,Footnote 2 the standard practice has been to create a link between it and the efforts of mission-educated poets among the Ẹgba of the nineteenth century.Footnote 3 Ewì is expanding in form and value and continues to attract new practitioners. The fact that it survives in various media – public performance, various print media including newspapers,Footnote 4 the audio disc and performance on radio and television – accounts for the tendency in recent times to characterize it as media poetry (Barber Reference Barber2007: 163). But for all its uniqueness and dynamism, the genre remains largely understudied. The first and only book-length study of an ewì practitioner to date is Ọlatunde Ọlatunji's Adebayọ Faleti: a study of his poems (1982).Footnote 5 The driving force behind a resurgence of interest in ewì three decades after the publication of that book has been an interest in the poetics of the genre (Fọlọrunṣọ Reference Fọlọrunṣọ1999; Nnodim 2002; Okunoye Reference Okunoye2010).

A new direction that the renewal of interest in ewì may take is to estimate the various ways in which individual ewì practitioners have contributed to its making. This becomes necessary because, in spite of the tendency to go as far back as a century in tracking the development of modern Yoruba poetry, the most remarkable developments in its evolution actually occurred in the last half century. Prominent among these are the use of the mass media in western Nigeria in broadcasting poetry from around 1960, the publication of the pathbreaking Ewì Ìwòyí anthology at the end of that decade (Akinjogbin Reference Akinjogbin1969), and the mass dissemination of ewì through waxed records, audio tapes and compact discs from the 1970s. The early 1990s also saw the flowering of a form of politically motivated ewì. Particular figures have featured in many of these developments and no proper history or study of the form will be complete without duly acknowledging the unique ways in which their visions and practices have shaped the tradition. Adebayọ Faleti, Lanrewaju Adepọju, Tubọsun Ọladapọ, Alabi Ogundepo, Yẹmi Ẹlẹbuibọn, Adelakin Ladeebo, Ayọ Ọpadọtun and Kunle Ologundudu are the better known of these. Adepọju and Ọladapọ are, without doubt, the most active promoters of the genre (Barber Reference Barber, Irele and Gikandi2004; Waterman Reference Waterman1990a). Their collections were among the first to appear in the early 1970s to mark the new awakening in ewì practice. They were also involved in promoting ewì in the media,Footnote 6 and later resigned from their jobs as broadcasters to start their individual companies in Ibadan.

This essay presents Lanrewaju Adepọju as a local intellectual within the Yoruba cultural environment whose poetic career sheds interesting light on Nigerian politics and related social issues. And because Adepọju's poems have not been available previously in English, the appendix to the essay offers a translation of Ìlú Le as a sample poem.Footnote 7 The online version of this contribution includes two more of his poems as well as the text of an interview with the poet. Apart from being one of the most visible poets in the ewì tradition in the past four decades, Adepọju has also featured prominently in major efforts at renewing the tradition. He is the most articulate promoter of ewì, complementing his practice with an exposition of the principles that underlie it. He is at the same time conscious of the sense in which he has enriched Yoruba poetry. Drawing on biographical information, an interview with the poet, and Adepọju's work in various media, the essay draws attention to the dynamics at work in the formation of the knowledge that the poet generates about ewì. In turn, this yields insights into the invention of culture in his immediate social environment.Footnote 8

Ọlatunde Ọlatunji's Adebayọ Faleti: a study of his poems has had some influence on the critical reception of ewì. Ọlatunji's effort to relate Faleti to his predecessors and others that came after him enables him to consider comparatively the works of many other poets, including Adepọju. He predicates his interest in Faleti's poetry on what he regards as ‘its concern with the timeless and the universal’ and the fact that ‘his disposition is philosophical’ (Ọlatunji Reference Ọlatunji1982: 116). He consequently adopts his work as the standard: ‘Most of the poets after Faleti, especially those who read their poems on radio and television, or perform them on discs, are, however, nauseatingly moralistic or didactic. They see themselves as sages out to expose societal ills or teach lesser men’ (Ọlatunji Reference Ọlatunji1982: 122). This critical standpoint has been so influential on the reception of the works of other Yoruba poets that many studies conducted within the context of the formal study of Yoruba poetry tacitly amplify or restate it.Footnote 9 The consequence is that a view of Yoruba poetry that privileges the values and outlook of a particular poet and uncritically applies them to assessing the works of others has been dominant. This, in a sense, denies the fact that the making of ewì is the collective achievement of its various practitioners. The result has been a rather subjective outlook, which does not seek a broad-minded understanding of the genre. This is untenable, for no tradition accommodates stasis. The study of Adepọju's work has probably suffered most from this unproblematic transference of values, judging from the works that claim to engage it specifically.Footnote 10 An alternative outlook on Yoruba poetry becomes necessary if we seek to appreciate the sense in which the work of each poet is unique. Their individual experiences become relevant if it is the case that their works reflect their circumstances and outlooks on life. In appraising the significance of Lanrewaju Adepọju in the making of ewì, this study correlates Adepọju's outlook on the function of the poet with his practice, estimating the effect of his politically charged creative imagination on his social standing and the reception of his work.

Even though Lanrewaju Adepọju has not been an object of any sustained scholarly engagement, various broad studies of ewì (Nnodim 2002; Reference Nnodim, Ricard and Veit-Wild2005; Fọlọrunṣọ Reference Fọlọrunṣọ2006; Ọlatunji Reference Ọlatunji1982) acknowledge his significance. Adepọju deserves attention in the study of ewì because he is one of its most prolific and influential practitioners. He is closely associated with a sub-genre of ewì that aspires to social criticism. This has earned him considerable popularity and influence in the Yoruba-speaking part of Nigeria and the anger of successive Nigerian administrations. But for all his output, his work remains understudied and the few critical engagements with his poetry (Fọlọrunṣọ Reference Fọlọrunṣọ and Eruvbetine1990; Reference Fọlọrunṣọ1997; Reference Fọlọrunṣọ2006) concentrate on his later work. This leaves room for a more wide-ranging engagement with his poetry, one that will not only identify phases in his development as a poet but also situate various trends in his work within an evolving poetic vision.

LANREWAJU ADEPỌJU – THE MAKING OF AN ARTIST

Adepọju attaches much value to his personal history and is always eager to draw attention to it. It not only chronicles his rise to prominence from a humble background but also highlights the sense in which his literacy despite a lack of formal education has enhanced his influence as a local intellectual. Born into a family of twelve in Okepupa, an agrarian settlement near Ibadan, Adepọju underscores the fact that he ‘did not go to school at all’ (Adepọju 2006: 1). He attributes this to the poverty of his parents as well as their ignorance about the value of Western education. His effort at self-education was initially stirred by the assistance of Muili Oyedele, his cousin, who took him through the first Yoruba primer. He attributes his literacy in spite of his ‘zero level education’ to his determination: ‘I wove basket, I sold firewood and did odd jobs to save enough money with which I bought my first book, ABD Aláwòrán in those days’ (Adepọju 2006: 1). He acquired literacy in Yoruba as a young adult and built on the foundation that this provided for his development. Adepọju was raised in a strict Muslim family. His father was a disciplinarian while his mother was ‘soft and caring’. His acquaintance with basic Yoruba values and immersion in the Islamic faith provided the moral platform for his development, while his interest in Yoruba oral traditions stirred his creative imagination. He attributes his decision to move to Ibadan to his desire to ‘continue my continuing education’ (Adepọju 2006: 1). The city gave him opportunity to acquire various vocational skills and to make use of the Western Nigeria Library, which he considered his second home. Adepọju's quest for literacy in Yoruba and English is significant in the context of the high premium that the Nigerian society places on certificates and formal education. His testimony as a self-taught man thus constitutes a major component of his story as a local intellectual and enhances his sense of self-worth and leadership, all of which he brings into his vocation as a poet. Literacy in particular empowered him as a modernizing agent in the practice of Yoruba poetry.

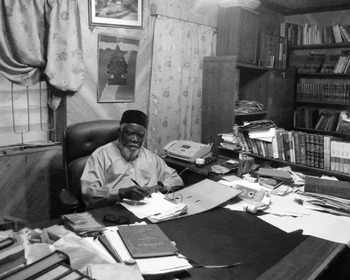

Figure 1 Adepọju: the poet at his desk

Adepọju wrote his first poem entitled Má ṣìkà mọ́ [Desist from doing evil] in 1960 but only had the opportunity to read it on Tiwa-n-tiwa, a programme on Western Nigeria Broadcasting Service that Laoye Egunjọbi was producing, in 1964. His most valued asset is a deep knowledge of Yoruba lore and facility with language. He makes no claim to inheriting the art of poetry because no member of his immediate family practised poetry in a formal sense. He first encountered poetry within his community and learnt early to appreciate such oral poetic forms as ìjálá, rárà and ẹsà that flourished around him. He cherishes values propagated by his immediate society – such as honesty, incorruptibility and consideration for others – as standards with which he claims to be appraising reality, and the foundation on which his outlook on life and society rests.

Adepọju has spent most of his adult life in Ibadan, working at various times as a houseboy, newspaper vendor and petrol station attendant. He became a proofreader with Ìmọ́lẹ̀ Òwúrọ̀ [Dawn Light] and Sunday Sun newspapers before going into broadcasting. His association with WNBS-WNTV started first as a freelance artist in 1964. He later became a contract officer with the programmes department. In his words: ‘Broadcasting and poetry overlap in a very complementary manner. Through broadcasting, my talent began to show. People discovered me. The Broadcasting House was a tough training ground’ (Adepọju 2006: 6). As broadcaster, Adepọju produced and presented programmes like Káàárọ̀ o ò jíire? [Good morning], Tiwa-n-tiwa [What is rightly ours], and Báríkà [Blessing/greetings]. But it was Ijínjí Akéwì [The poet at dawn], aired at 6.15 a.m., that offered him the best opportunity to exhibit his talent. It featured short ewì performances and attracted such poets as Adebayọ Faleti, Olatubọsun Ọladapọ and Alabi Ogundepo, who were all associated with the station. Adepọju links his decision to leave broadcasting for a career as a professional poet to a desire to be free from censorship on the part of his employers: ‘They wanted to start publishing them [his poems] with the copyright reverted to the corporation. It was the copyright issue that we disagreed upon, and which led to my eventual disappearance from the broadcasting scene’ (Adepọju 2006: 8). He subsequently established his own recording studio and record label.Footnote 11

Apart from exposure to the world of books and broadcasting, religion has had a remarkable influence on Adepọju. Though raised in a Muslim environment, he veered for a while into mysticism, identifying with a group known as Servers of Cosmic LightFootnote 12 for about twelve years. His dramatic return to Islam in 1985 transformed his work by injecting into it a fundamentalist Islamic vision in the Sunni tradition.Footnote 13 The turning point in his religious orientation came after reading Muhammed Husayn Haykal's The Life of Mohammed (1976) while visiting London. The book stirred the quest for a more fulfilling experience of Islam, transformed his outlook, and accounts for the intense religious commitment he later expressed by founding the Ibadan-based Jam'iyyatul-Ukhuwwatil-Islamitil ‘Aalamiyah [Universal Muslim Brotherhood], an organization which he serves as its Amir or President.Footnote 14 This religious experience has marked a radical departure in his work and Adepọju currently combines his calling as a poet with a senior role in the leadership of the umbrella organization of Sunni Muslims in Nigeria.Footnote 15

Although Adepọju has emphasized the impact of his return to a conservative form of Islam on his poetic imagination, it is projected only superficially within the broader theistic vision that emerges in his work as a whole. With the obvious exception of poems in which he sets out to propagate particular Islamic doctrines, the vision that pervades his work constantly shifts between the Islamic and the ecumenical, blending Christian, Islamic and traditional Yoruba outlooks. This suggests either a split consciousness underlying Adepọju's work or a deliberate strategy aimed at popularity and relevance in a multi-religious society. His Oríkì Olódùmarè, Footnote 16 a work that conceptually integrates Islamic, Christian and traditional Yoruba theistic visions, testifies to this.

ADEPỌJU'S VISION OF POETRY

While Lanrewaju Adepọju makes no claim that earlier Yoruba poets influenced his work, he conceives of his vocation largely in terms dictated by a received tradition of artistic responsibility within the traditional Yoruba society, as well as a moral vision that issues from his religious persuasion. He appreciates poetry as the product of intense contemplation, seeing the poet as both an artist and an influential figure. His vision of poetry emerges from the title of his only published collection of poems, Ìrònú Akéwì [The poet's reflection]. He sees his craft as so engaging that the act of creation can only be a product of sustained reflection:

This outlook on the vocation of the poet does not accommodate hasty and thoughtless utterance. In Adepọju's estimation, the business of creating poetry is so demanding that only a few people qualify as poets. As he states in Ìrònú Akéwì: ‘Ojúlówó akéwì tí mo mọ̀,/Wọn kò pogún/Ayédèrú akéwì tí mo mọ̀,/Nwọn pọ̀ jẹyẹ oko lọ’ (Adepọju Reference Adepọju1972: 1) [The genuine poets that I know are fewer than twenty/The not-so-serious ones known to me/Exceed birds in the wild in number]. The rigour that he ascribes to the making of poetry suggests that he subscribes to a vision of poetic craft that recognizes a great deal of artistic discipline fused with social sensitivity. It is no surprise that he also attaches importance to originality. He sets an incredibly high standard for poets in a way that rules out obvious borrowings from other artists:

This standpoint in a way poses a question as to what constitutes Adepọju's idea of tradition and the shared heritage of poets. He devotes little attention to theorizing a common tradition on which Yoruba poets draw, but instead clarifies his outlook on poetry and, in the process, expounds his vision of socially situated poetry. The poet who emerges in his theory and practice of poetry is intensely sensitive to the affairs of the immediate society and feels a considerable sense of responsibility to propagate justice, truth and responsible governance: ‘The role of the poet is to educate and create public awareness, to monitor political promises and their implementation. It is also to remind the public office holders to be alive to their responsibilities. … Whenever one looks at the political situation in Nigeria today, what is happening calls for the intervention of the poet most of the time’ (Adepọju 2006: 10). He does not see any potential conflict between religion and culture so long as religion provides the ethical basis for the poetic imagination:

I have never believed that religion and culture are antithetical; rather they are complementary to each other. In Islam, for instance, there is a culture of justice, equity and humility as well as honesty in relation to others and total submission to the authority of Almighty Allah. What is objectionable to Islam is idol worship which some ignorant people think is part of their culture … . That is why I have waged relentless war against it and I have expressed my religious beliefs about all these. (Adepọju 2006: 5)

In works that are critical of public office holders, Adepọju thrives on the assumption that he is close enough to the populace – from whom he thinks the politicians are alienated − to know their expectations. The poet in his opinion is thus an activist: ‘An akéwì is a poet who mirrors the society, using events around him to create imagery for entertainment, information, education and admonition as well as counselling, as the case may be … . He must not sit down and watch complacently when things are not normal in the society’ (Adepọju 2006: 10). This is probably the most distinctive aspect of Adepọju's poetics. The poet should be an advocate of the violated, boldly propagate the best of values, and confront whatever constitutes a barrier to realizing the shared desires that flow from these. But the poet constantly creates the impression that his outlook represents the perspective of most members of the society. This underestimates the complicated nature of contemporary society. His way of assigning the poet a special role emerges from the way he accords the poet the power to speak for all and serve as the moral conscience of his society. Adepọju's commitment to the social uses of poetry only partly accounts for his engagement. So long as the chaotic state of affairs that prompts his responses persists, his type of poetry will remain both necessary and popular.

Adepọju's understanding of the mandate of the modern Yoruba poet tolerates the commercialization of ewì to make the poet a publicist either for government or for individuals. This equates what the akéwì does with the mandate of media organizations and advertising firms. He rationalizes this by maintaining that the vision of the artist as an implacable critic is unjustifiable: ‘An akéwì does not need to be an opposition party to all programmes and activities. As he is able to rebuke where people misbehave, he should also acknowledge good things and virtues in some decent politicians where such occur … . If one continues only to see the ugly side of people, everybody will lose respect for one’ (2006: 14). Not many will agree with Adepọju on this. In fact, Adeyinka Fọlọrunṣọ establishes a link between the commercialization of ewì and what he regards as the waning popularity of Adepọju's poetry:

Adepọju's praise-singing tendencies are reminiscent of the oral mode of performance traced to Ọyọ where court bards performed … mainly for entertainment … . Most of the praise-songs Adepọju composed during the political struggle in Nigeria in 1983 show his bias, and made him lose the confidence and respect of the people he was supposed to serve. (Fọlọrunṣọ Reference Fọlọrunṣọ and Eruvbetine1990: 260)

Fọlọrunṣọ substantiates his argument by underscoring the inconsistency of Adepọju at this time, especially the ease with which he terminated his support for Bọla Ige of the Unity Party of Nigeria and endorsed the candidature of Ọmọlolu Olunlọyọ of the National Party of Nigeria in Ọyọ State. Many of Adepọju's fans cite the effort of the poet to present the position of the Babangida government in Àlàyé Ìjọba [Government's explanation], which came out as a sequel to Níbo là ń lọ? in 1987 as the very act that made him lose the confidence of many of his admirers – because Níbo là ń lọ? appeals to many as presenting him at his best.Footnote 18

THE DEVELOPMENT OF ADEPỌJU'S POETIC CONSCIOUSNESS

There is a link between Adepọju's vision of poetry and his development as an artist. He is one of the few poets to have produced ewì in various media. If Ìrònú Akéwì is to date his only book of poems, he also played a major role in pioneering the production of ewì on disc. Rita Nnodim acknowledges that ‘Ọlatubọsun Ọladapọ as well as Lanrewaju Adepọju appropriated the technology of waxed records and later cassettes to produce lengthy poems’ (Nnodim 2006: 155). Most of his work therefore circulates on audio tapes in the Ewi Hit Hot Series. This accounts for the broadening of his audience as the tapes penetrate widely in the Yoruba-speaking area. All the same, much of Adepọju's work thrives on the principles that sustain the tradition of ewì performance on radio, attaching importance to topicality and aspiring to mass appeal. This bears out the fact that ewì is not an ideologically neutral practice but instead articulates popular viewpoints within an imagined Yoruba community. Adepọju's audience constantly shifts between the Yoruba-speaking community in south-western Nigeria and the country at large, depending on the issues he engages. The shift from the fixed notion of his audience that emerges from Ìrònú Akéwì – one constituted by literate Yoruba people – to the country-wide appeal of Ẹ̀yin Ọmọ Nigeria indicates a growing sense of relevance on the part of the poet and testifies to the possibilities of broad engagements in ewì.

Adepọju's early poetry, from the 1960s to the mid-1980s, projects Yoruba ethics, culture and religion. Má mọ́bùn ṣaya [Never marry a dirty woman], Ènìyàn laṣọ mi [Humanity is my cloth/covering], Ọ̀rọ̀ Obìnrin [Concerning women] and Ìgbà layé [Times change] – all of which are in his 1972 collection – propagate Yoruba values relating to womanhood, communality, and the transient nature of life respectively. But other poems in the same collection are critical of practices that the poet considers unreasonable. For instance, Àwọn Onínàákúnàá [Wasteful spenders] decries the subtle manner in which aṣọ ẹbí, the special uniform made for particular social functions among the Yoruba, promotes vanity, waste and flamboyance. Other poems in the collection make efforts to balance issues in a way that projects a liberal outlook. For instance, Ìwà Ọkùnrin [Antics of men] and Má mọ́bùn ṣaya present counter-arguments that critically appraise the antics of men and women respectively. This has given way to rigid subjectivity in Adepọju's later poetry. Díẹ̀ Nínú Oríkì Ṣàngó [A short praise of Ṣango], which eulogizes Ṣango – the Yoruba god of thunder – is not likely to find a space in his recent work, which is very discriminating in religious terms. His fundamentalist Islamic vision comes out strongly in Ọ̀rọ̀ Olúwa [The word of God] (1990), Takúté Ọlọ́run [The divine trap] (1992), Idájọ́ Òdodo [Righteous justice] (2000), Ìronúpìwàdà [Repentance] (1993), and Oríkì Olódùmarè [Celebration of the Supreme Being] (2000).

A new phase in the development of Adepọju's work, starting from the 2000s, has seen him deploying his poetry in publicizing achievements of administrations and celebrating dignitaries. Works produced within this practice are normally commissioned and are intended to sell the patrons to the public. Adepọju does not see this as contradicting his professed commitment to objectivity and truth. With regard to his engagement with public office holders, he maintains that the business of government is important enough to attract the attention of poets. He prefaces Ìjọba Gbénga Daniel with an apologia: ‘Àwọn aṣáájú wa ò ṣe yọ sílẹ̀ nínú iṣẹ́ orin ewì/Sààsà lètò tí wọ́n ṣe tí ò ní kàn wá/Ohun tí wọ́n bá fowó wa ṣe/Sèríà ni ko yẹ gbogbo wa/Òun la fi lè mọ yàtọ̀ nínú olóṣèlú/Atòjẹ̀lú lásán/Kírọ́ ó sálọ kó kòótọ́ ọ̀rọ̀’ [We cannot discountenance our leaders in ewì/There is hardly any policy that they promote that does not concern us/It is necessary to show concern/About how they manage public resources/That's the way we will know the difference between constructive politicians/And mere riders on the gravy train/So as to dispel lies and reveal the truth] (Ìjọba Gbénga Daniel). In Ìjọba Tinúbú [Tinubu's Administration], Tinúbú Fọmọyọ [Tinubu Excelled] and Ìjọba Gbénga Daniel [Gbenga Daniel's Administration], all recorded ewì within this sub-genre, the poet stresses that his impressions of the various administrations are a product of his personal investigations. But this does not stop him from constantly rating his patrons in superlative terms. In praising the accomplishments of Gbenga Daniel as governor of Ogun State, for instance, he says: ‘Bó bá jẹ́ ti bí wọ́n ti ń ṣèjọba/Àpẹẹrẹ gidi lOlúgbénga’ [As far as governance is concerned, the administration of Olugbenga is a model]. Equally, he celebrates Bọla Tinubu as governor of Lagos State in Ìjọba Tinúbú, saying: ‘Tinúbú tayọ àgbá òfìfo/Ọpọlọ tó jíire ló fi ń ṣiṣẹ́ ire’ [Tinubu is far from being an empty barrel/Because he excellently executes good jobs with a sound mind]. Tinúbú Fọmọyọ (the full text of which is available in the online version of this article) exemplifies the work of the poet in this new phase in the diligent way it advertises and documents the achievement of the government. The value of this effort for the patrons consists in its ability to reach members of the public, most of whom do not have access to published documents on the track records of governments in their preferred medium.

In spite of the shifts in Adepọju's poetry in terms of concerns and consciousness, the desire to instruct, mobilize and inspire action continues to drive his work. His favourite formula for signing off in his recorded performances – ‘Èmi ni Láńrewájú Adepọ̀ju/Tí í forin ewì kìlọ̀ ìwà/ṣe kìlọ̀’ [I am Lanrewaju Adepọju/The one who uses ewì to guide conduct/warn] – confirms this. Má ṣìkà mọ́ probably set the tone for the didactic in his work in the sense that the image of the poet created in the poem pervades his poetry. This has manifested in various forms. He probably uses poetry to propagate partisan political causes more than any other modern Yoruba poet. His work celebrating Ọbafẹmi Awolọwọ, whose political project inspired a pan-Yoruba political consciousness, illustrates this. Christopher Waterman (Reference Waterman1990b) has also attributed this role to Yoruba musicians in the Juju tradition. Not content with merely endorsing Awolọwọ's policies, Adepọju went ahead to demonize Awolọwọ's opponents:

Adepọju's work continues to construct a pan-Yoruba political vision, and the fact that he openly identified with Awolọwọ's political aspiration may be seen as a way of promoting the Yoruba cause. This in turn has helped him to recommend himself as a mouthpiece of the people. But whatever gain such a project of strategic self-positioning can earn any poet will be lost if he identifies with unpopular candidates. The question that arises is whether a poet should take the risk of participating in partisan politics, considering the damage that this can do to his reputation. Related to this is the question whether professionalizing the practice of ewì is consistent with the aspiration of the poet to fairness and objectivity. Further proof of the didactic quality of Adepọju's work is that it propagates ideals that are based on his religious convictions without considering the implication of this for sustaining his audience. For instance, the Islamic vision in his recent poetry does not tolerate traditional Yoruba assumptions about ancestors. He labels those practising traditional Yoruba religions as aṣẹbọ [idol worshippers] in Oríkì Olódùmarè.

Adepọju was at his best as an advocate of the Nigerian masses in the days of the military. This is why Ìlú Le, which is appended with a translation to this essay, gives some insight into the passion with which he did this. His bold engagement with the military was a way of defending the interest of the common people. This explains why studies of resistance to the military in Nigerian popular culture (Bọdunde Reference Bọdunde and Bọdunde2001; Olukọtun Reference Olukọtun2002; Reference Olukọtun2004; Williams 1999) accord his work considerable attention. The annulment of the 12 June 1993 presidential election in particular provoked the rage of Adepọju and many other Yoruba creative artists, inspiring bold and rousing ewì.Footnote 19 Adebayọ Williams remarks that ‘Lanrewaju Adepọju and Gbenga Adewuyi (sic), much lionized as ewì poets, were so daring in their personal attacks, so liberal with savage excoriations, that between them they probably cost the Babangida government its remaining authority and legitimacy in Yoruba-land’ (Williams 1999: 358). Such other Yoruba poets as Faleti, Ọladapọ, Adewusi and Ologundudu also responded to the aftermath of the 1993 election. What many of them only engaged under the pressure of the moment is what regularly provokes Adepọju's poetic response. The most remarkable of his works during the military era are Ìpinnu [Resolve], Níbo là ń lọ? [Where are we heading?], Ẹ̀tọ́mọ̀nìyàn [Human Rights] and Ìlú Le [Hard Times].Footnote 20

Nothing illustrates the shifts in Adepọju's consciousness more than the strategies of self-definition that he adopts, a feature that probably originated in the context of ewì performance in the mass media. He signs off his performances at various times as ‘Láńrewájú Adépọ̀jù tí í fohùn dídùn’ [Lanrewaju Adepọju whose voice is melodious] (Ọbáfẹ́mi Awólọ́wọ̀), ‘Láńrewájú, Ọba Akọrin/Ajagunlà Mùsùlùmi, Aláàsà-Ìbàdàn/Tó maa ń forin ewì ṣe ’kìlọ̀’ [Lanrewaju, the king of singers/Crusader of Islam, holder of the Alaasa title in Ibadan/The one who instructs with ewì] (Kádàrá), and ‘Bọ̀rọ̀kìní akéwì tí í korin/Ewì ni tòjò tẹ̀ẹ̀rùn’ [The prominent poet who chants/At all seasons] (Ikú Awólọ́wọ̀). Signing off has to do with the occasion, and the strategy helps in no small way to authorize the diverse tendencies in his work. This then creates a link between the subject and the form of identity he asserts. Drawing on a multiplicity of identities enables the poet to exhibit the diverse identities that he constructs for himself and to assert his prominence within the circle of Yoruba poets.Footnote 21

LANREWAJU ADEPỌJU AND THE EWÌ TRADITION

It is necessary to situate Adepọju's work in the wider context of the making of ewì in the last half a century. While Faleti, who started producing ewì earlier, acknowledges his debt to both Yoruba and English traditions of poetry in terms of the ideas and conventions that inspired his work (Faleti 2006), Tubọsun Ọladapọ, with whom critics naturally compare Adepọju, draws attention to the immersion of his work in social events. Adepọju, on the other hand, constantly strives to assign social value to both poet and poetry. Thus, while the extension of the possibilities of ewì in the works of Faleti and Ọladapọ is mainly formal, it is largely functional in Adepọju's. Adepọju's work enjoys visibility due to its political posture and the poet's assertive nature. These combine constantly to link him with his output and publicize his political and religious concerns. He gave practical expression to the primacy of function in his work by eliminating musical accompaniment from his ewì right from Tani ń bínú [Who is angry?], produced in 1997, on the basis that it impedes the discursive import of his poetry:

Estimating the imprint of Lanrewaju Adepọju on modern Yoruba poetry necessitates looking into and beyond his work to discover the ways in which his unique concepts and practice of poetry have influenced the tradition. Apart from the fact that he has produced ewì in all the media so far adopted for it, Adepọju is one of its most visible contemporary practitioners.Footnote 22 But his claim to professionalizing ewì carries a lot of implications, not least of which is the corrupting influence of commercialization. Adepọju will justify producing Ìjọba Tinúbú [Tinubu's administration] and Àwọn Alágbárí [The smart ones], which publicize the activities and achievements of Bọla Tinubu and Gbenga Daniels as governors of Lagos and Ogun States respectively, on the basis that they document verifiable achievements of their administrations.Footnote 23

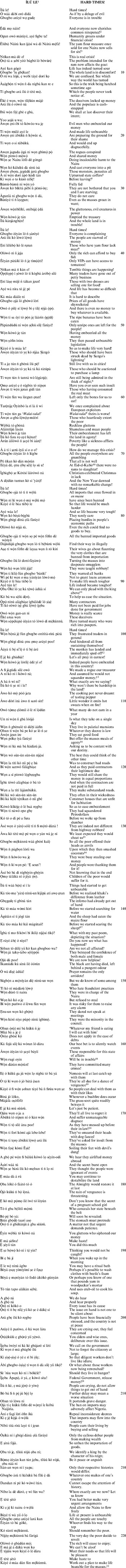

Figure 2 Adepọju: the poet in his studio

Adepọju must take credit for popularizing a vision of ewì that assigns it definite social value, especially in that it is capable of correcting, instructing and influencing conduct. Thus, his work consistently adopts relevant images in representing it. For example, ewì is ‘pàsán’ [whip], ‘ìwàáṣù’ [sermon/admonition], and ‘ọ̀rọ̀ ọgbọ́n’ [word of wisdom] in Tani ń bínú? [Who is angry?]. It is also ‘orin ọgbọ́n’ [song of wisdom] in Àṣàyàn Ọ̀rọ̀ (2009). This outlook on ewì implies that Adepọju assigns the poet considerable social significance. The poet in Àwon Alágbárí is ‘agbẹnusọ fún gbogbo aráyé’ [advocate of humanity]. He places the poet on an elevated moral platform that enables him to inform, correct and educate others, the very element that Ọlatunji finds objectionable in the works of many practitioners of ewì and the basis on which he places Faleti's work in a special category. The fact that Adepọju maintains this vision largely accounts for the passion with which he decries opposition to his work and the antics of his critics. Thus, he dismisses those alleged to be peddling rumours about him as ‘aṣìwèrè’ [mad people] in Àṣàyàn Ọ̀rọ̀.

Adepọju pioneered the use of daring and direct verbal assaults in ewì, even though Kunle Ologundudu, a younger practitioner, has since made this the defining feature of his poetry. While the inspiration for this derives from the immunity that Yoruba poets enjoy in correcting erring members of the community, it is also possible to argue that the passion with which he executes it in part derives impetus from the style of sermonizing that his form of Islam sustains. For instance, he dismisses Prophet Temitopẹ Joshua, founder of the Lagos-based Synagogue Church of All Nations as ‘oníwàyó ìgbàlódé’ [modern day fraudster] and calls Olowoporoku, a self-styled Islamic cleric in Ibadan, ‘alágbárí irọ́, aṣìwèrè’ [dubious one, madman] in Tani ń bínú?

It is significant that consciousness of his audience in Adepọju's work has evolved with the broadening of his focus from an initial concern with his ethnic formation to an engagement with broader national issues. The consequence is that his audience now shifts constantly between his ethnic base and the entire Nigerian nation. He addresses the Ọ̀rọ̀ Iṣáájú [Foreword] to his 1972 collection to ‘Ẹ̀yin Ọmọ Yorùbá’, a category that evokes the totality of Yoruba people, and thereby invents an audience which coincides with a cultural group. This is probably the earliest pointer to the intense political orientation of his poetry on disc and audio tapes. The strategy of addressing an audience is an index of the public orientation of Adepọju’s work. His concern at every point dictates those he makes his primary audience. While Níbo là ń lọ? [Where are we heading?], which blames the Babangida junta for the inflationary trend that trailed the Structural Adjustment Programme in the late 1980s, is addressed to the same administration, Ikú Awólọ́wọ̀ [The Death of Awolọwọ] identifies the Yoruba as his main audience. The ease with which he invokes a pan-Yoruba consciousness in order to draw attention to issues bearing on the political fortunes of his immediate cultural community reveals his capacity for inspiring ethnic solidarity. But if the Yoruba constitute a cultural unit in Ìrònú Akéwì, much of his later work that also addresses developments to do with their political fortunes – such as the aspiration of Ọbafẹmi Awolọwọ and Moshood Abiọla, two Yoruba politicians, to the Nigerian presidency – envisions the same people as a political formation. It is no surprise that Ẹ̀yin Ọmọ Nigeria [Dear Nigerians], which promotes the political project of Atiku Abubakar in the face of perceived political persecution from Olusẹgun Ọbasanjọ,Footnote 24 indicates a considerable widening of his audience consciousness.

Ideological shifts do not seem to have had any significant influence on the genres that Adepọju employs. The two major forms on which his early poetryFootnote 25 drew – oríkì and satirical songs – remain his favourites. Thus, Oríkì Òjó [The attributes of Ojo], Díẹ̀ Nínú Oríkì Ṣàngó, and Kìnìún Olólà Ijù [Lion – surgeon of the wild] fall back on the oríkì tradition while Àwọn Onínàákúnàá, Ọ̀rọ̀ Obìnrin, Ìwà Ọkùnrin, Má mọ́bùn ṣaya and Àwọn Aláhesọ are didactically critical. His later poetry seems to thrive on the laudatory and the critical – the main passions that sustain his poetry. The oríkì convention experiences remarkable extension in Oríkì Olódùmarè, which expounds his theistic vision. The two genres that dominate Adepọju's practice, in spite of their superficial divergences, ultimately rely on hyperbole, imbuing his work with an uncommon persuasive force. For instance, in a bid to draw attention to the legacy of the Tinubu administration in Lagos State, he says: ‘Ìjọba Tinúbú/Ti ṣètò ìtọ́jú ojú fún àìmòye ẹ̀dá’ [Tinubu's administration/Has provided eye-care service to countless people] in Ìjọba Tinubu. And in graphically depicting the hardship that people faced under the Babangida regime in Níbo là ń lọ? [Where are we heading?] he says: ‘Eyín tó ń tí ń jẹran lọ́jọ́ sí/Wọ́n tí ń jeegun ẹran’ [Those that could afford meat for meal in the past/Are now only able to afford meatless bones].

It is no surprise that Adepọju sums up his significance as a poet by making a claim to modernizing and professionalizing ewì. A way to appreciate this is to compare it with how contemporary Yoruba cultural producers, while competing for the attention of their audience, draw attention to what they consider unique about their work to demonstrate their inventiveness. This is particularly the case with musicians in the genres of Jùjú, Fújì and Wákà, who make claims to inventing variants of the genres. While Adepọju's oeuvre testifies to his significance, the project of modernizing ewì is still in progress – and so other poets, too, can draw attention to the ways in which they have extended the tradition. Adepọju's more controversial claim has to do with professionalizing ewì. While not many will contest this, knowing that he founded Ẹgbẹ́ Akéwì Yorùbá [Association of Yoruba Poets], the implications that professionalizing the practice hold for the integrity of ewì may make this a liability and not an asset – because the idea of professionalizing ewì is likely to imply commercialization.

CONCLUSION

All told, Adepọju remains an influential figure in the making of modern Yoruba poetry, and his ideas about ewì are as important as his work. His poetry reveals an initial liberal and secular orientation, since overshadowed by an increasing appropriation of issues of public importance as legitimate subjects for poetic engagement. To explore his work over the past few decades is to gain insight into the vicissitudes of Nigerian public life that it has been exploring. Adepọju's talent is not in doubt, neither is his courage to challenge repressive regimes and ridicule erring leaders. He has suffered more harassment, interrogation and intimidation at the hands of different administrations in Nigeria than any other Yoruba poet. Adepọju's growing association with public office holders, while testifying to ewì's popularity, may also portend danger for his objectivity. The work of Kunle Ologundudu,Footnote 26 the ewì practitioner most indebted to Adepọju's politically charged poetry, exemplifies the damage that submitting the poetic imagination to the transient dictates of political expediencyFootnote 27 can do to the social standing of a poet and the integrity of his art. The best of Adepọju's workFootnote 28 is devoid of partisan agitation, has enduring value, and articulates the shared expectations of his audience. Though mediated by his discursive affiliations and subjectivity, his ewì remain an indispensable source of information for many people in the Yoruba-speaking part of Nigeria. The eagerness with which this category of his audience awaits his responses to major events testifies to the power of his ewì and accounts for the influence he continues to have on younger poets.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The research on which this study is based was conducted with a British Academy Visiting Fellowship at the Centre of West African Studies, University of Birmingham between October 2006 and January 2007. An earlier version of the article was presented at the Afrikanistisches Forschungskolloquium of the University of Bayreuth, Germany, on 9 June 2009. The author gratefully appreciates the helpful comments of the anonymous Africa reviewers and the assistance of Sọji Bisade-Phillips, Babatunde Ẹkundayọ, Daniel Abiọdun, Ṣọla Ajibade and Steve Ogundipẹ at various stages of preparing the article.

Appendix

ÌLÚ LE: A SAMPLE ADEPỌJU POEM

Lanrewaju Adepọju performed and recorded Ìlú Le [Hard times], the text of which follows, in 1980, even though it reacted to experiences in Nigeria in the dying days of the military administration of Oluṣẹgun Ọbaṣanjọ. Ọbasanjọ handed over to the elected government of Shehu Shagari in 1979, but the nation felt the impact of the economic policies of his administration beyond his tenure. This explains why it could still provoke an angry response from Adepọju many months after another government had assumed office. Ọbasanjọ emerged as military head of state after the death of Murtala Muhammed in a coup on 13 February 1976. He was until then the deputy of the assassinated leader. Though his administration endeavoured to build infrastructure, the economic prosperity of the period also ushered in inflation. In spite of the prosperity brought by the oil boom, there was a brief period of recession from 1978 to 1979, although the economy recovered in 1981. Restrictions that the Ọbasanjọ regime placed on imports, mentioned in the poem, directly affected economic activities and the lives of ordinary people – and Adepọju's concern here is to articulate the plight of the masses.

Ìlú Le represents Adepọju's work in many ways. For him, the poet's ability to respond promptly and boldly to the plight of the masses is an index of his worth and ability. Apart from being topical, the poem also relies on caustic verbal assault, exaggeration and repetition. Contrary to the trend in his later works, the poet avoids direct reference to the political actors behind the events that he is reflecting on in Ìlú Le. Overt references such as we encounter in Níbo là ń lọ?, a reaction to the inflationary trends under the Babangida regime in 1987, are absent here. But Ìlú Le nevertheless creates the impression that the Ọbasanjọ regime was not acting in the best interests of the populace. This readiness to demonize Nigerian public office holders has endeared Adepọju's work to his audience.

As in every case of translation from ‘deep Yoruba’, the English translation of the poem, even though it is the work of the poet, is at best a shadow of the original. Apart from the sense that the lines convey, tonality, which plays an important role in Yoruba and injects a great deal of poetic value into most genres of Yoruba poetry, is lost in the process of translation. Yoruba is a tonal language and many genres of Yoruba poetry consequently strive to achieve the harmony of sense and sound. This disappears in the process of translating Yoruba poetry into English. As Niyi Ọṣundare (2000: 15), a poet of Yoruba extraction using the medium of English, notes,

while English is a stress-timed language, Yoruba is a syllable-timed one operating through a complex system of tones and glides. In this language, prosody mellows into melody. Sounding is meaning, meaning is sounding. The music, which emanates from the soul of words is an inalienable part of the beauty of the tongue. Tone is the power-point, the enabling element in any Yoruba communicative event.

What the English rendering of the poem retains is the raw anger of the poet and the passion with which he articulates the suffering of the masses. Even though Adepọju originally transcribed and translated the poem, I had to intervene each time it became necessary to make certain expressions reasonably intelligible to people who cannot access the texts in Yoruba. To this extent, some measure of collaboration between the poet and the present researcher facilitated the presentation of the texts of Adepọju's poetry in translation in the print and online versions of the article. The fact that most of the lines of the translated version of Tinúbú Fọmọyọ, in particular, are cast in passive sentences is testimony to his effort at approximating the syntactic structure of the poem in the original version.

NOTE

Supplementary material accompanies this paper on the Journal's website (http://journals.cambridge.org/afr).