Implications

A systematic assessment of heat stress impacts on livestock adaptation is needed to identify the appropriate biomarkers to quantify heat stress responses in domestic livestock. Such an approach may identify both phenotypic and genotypic traits, which may be useful indicators of heat stress susceptibility or tolerance in different livestock species. These biomarkers may be included in the breeding programmes in an effort to develop thermo-tolerant breeds using marker-assisted selection. Such efforts may help to identify the appropriate agro-ecological zone specific breeds. This may provide a mechanism for sustained livestock production in the changing climate scenario.

Introduction

Among the environmental variables affecting animals, heat stress is one of the factors making animal production challenging in many parts of the world (El-Tarabany et al., Reference El-Tarabany, El-Tarabany and Atta2017). Although animals can adapt to climatic stressors, the response mechanisms that ensure survival are also detrimental to performance (Pragna et al., Reference Pragna, Sejian, Soren, Bagath, Krishnan, Beena, Devi and Bhatta2018). The vulnerability of livestock to heat stress varies according to species, genetic potential, life stage, management or production system and nutritional status (Das et al., Reference Das, Sailo, Verma, Bharti, Saikia, Imtiwati and Kumar2016). Moreover, under the testing environmental conditions animal productivity is affected resulting in economic losses for livestock industries. It is important that efforts to understand the adaptive responses of the domestic livestock are taken. This may pave the way for identification of various biological markers that can be used to quantify heat stress responses. Identified markers may then be incorporated into breeding programmes in an attempt to develop thermo-tolerant breeds’ specific to different agro-ecological zones.

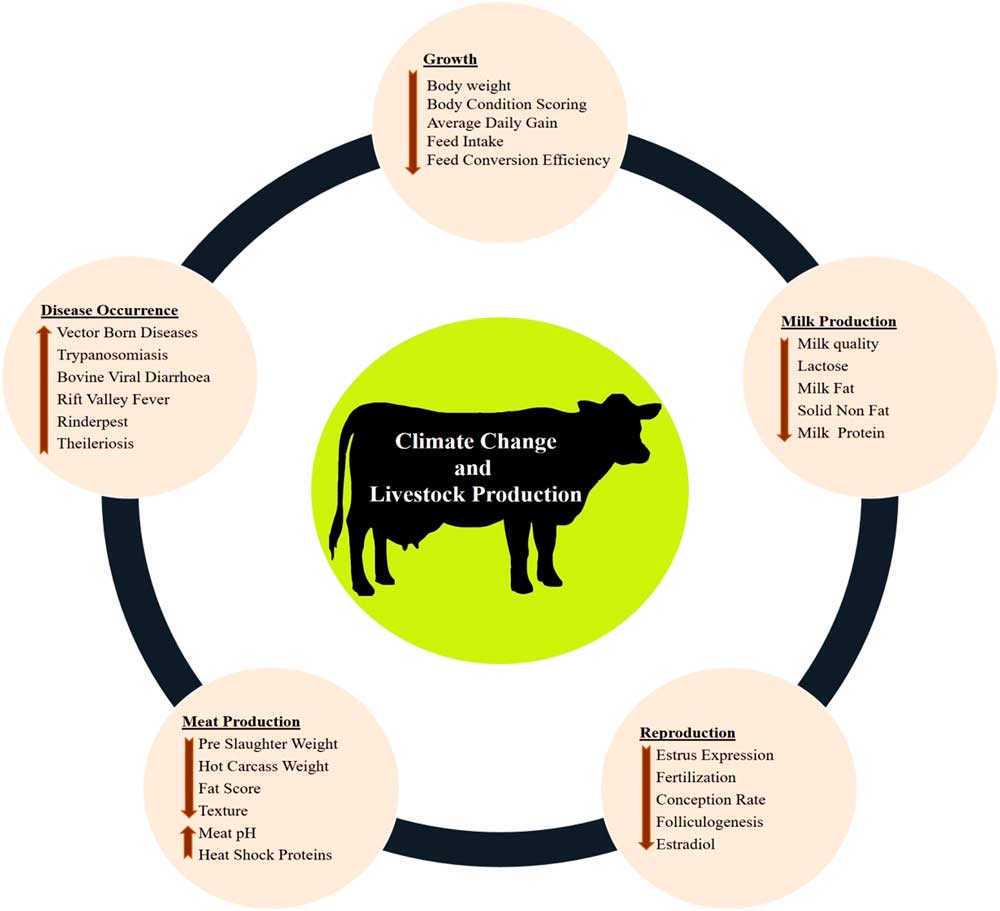

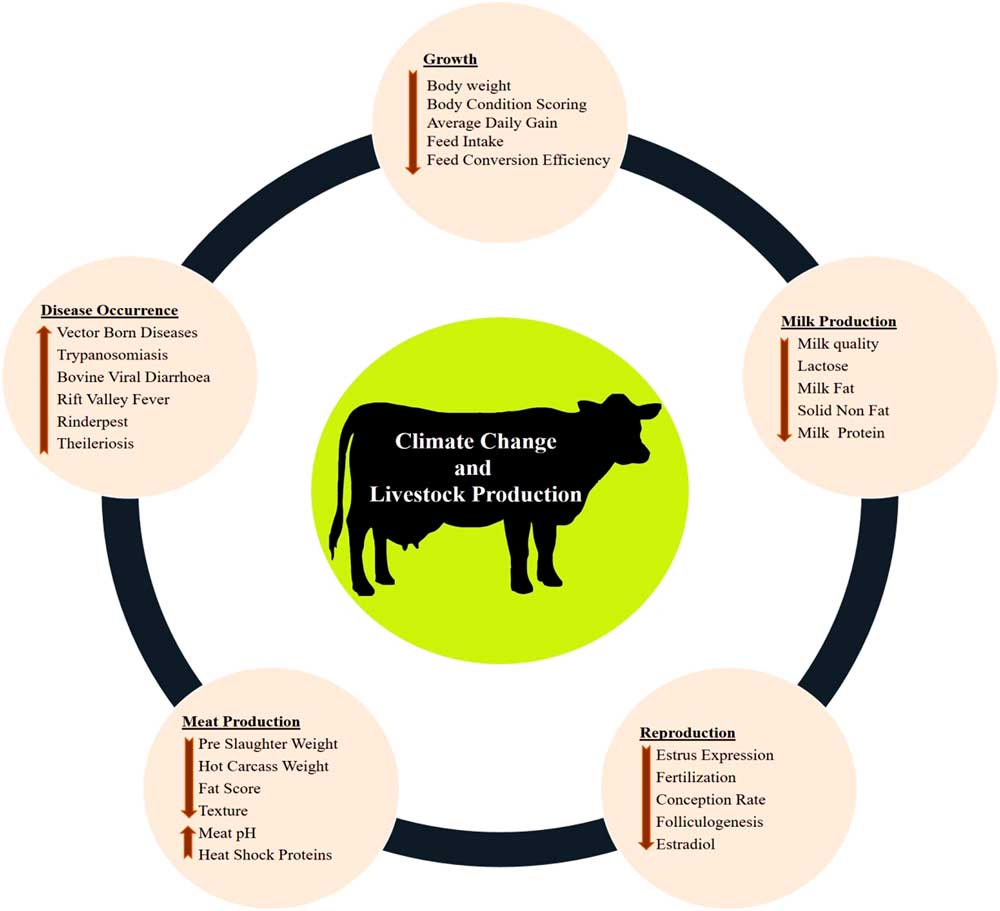

The various impacts of climate change on dairy cattle are presented in Figure 1. Heat stress was found to influence most of the productive functions in livestock (Figure 1). This is very crucial for the adaptive processes as generally the animals try to deviate the energy from the productive pathway to support vital adaptive mechanisms (Nardone et al., Reference Nardone, Ronchi, Lacetera, Ranieri and Bernabucci2010). Heat stress affects the growth performance (Baumgard et al., Reference Baumgard, Rhoads, Rhoads, Gabler, Ross, Keating, Boddicker, Lenka and Sejian2012), milk production (Das et al., Reference Das, Sailo, Verma, Bharti, Saikia, Imtiwati and Kumar2016), reproductive performance (Rhoads et al., Reference Rhoads, Rhoads, VanBaale, Collier, Sanders, Weber, Crooker and Baumgard2009), meat production (Archana et al., 2018) and disease occurrences (Rojas-Downing et al., Reference Rojas-Downing, Nejadhashem, Harrigan and Woznicki2017). The adverse impacts of heat stress on these productive functions depend on species and breed differences and the magnitude of this impact determines the adaptive potential of the animals.

Figure 1 Various impacts of climate change on livestock production. Climate change can directly negatively influence growth, milk production, reproduction and meat production. Further, climate change can indirectly reduce livestock production through sudden disease occurrences.

This review is an attempt to collate and synthesize information pertaining to livestock adaptation to heat stress. Special emphasis was given to cover the newly emerging concept of multiple stressors impacting livestock production, particularly in extensive systems. Efforts were made to cover in detail the various adaptive mechanisms of livestock to heat stress challenges. Efforts were also made to cover some of the advanced technologies available to quantify heat stress responses in livestock. Through the review literature, several biological makers of both phenotypic and genotypic origin were identified. In addition, some of the salient ameliorative strategies, which can aid in animal adaptation to heat stress challenges, are discussed. Several future researchable issues are presented towards the end of this review.

Livestock, climate change and food security

Climate change affects food security in complex ways. Climate change affects all dimensions of food security and nutrition: food availability, food access, food utilization and food stability (Rojas-Downing et al., Reference Rojas-Downing, Nejadhashem, Harrigan and Woznicki2017). Climate change is seen as a major threat to the survival of many species, ecosystems and the sustainability of livestock production systems in many parts of the world (Baumgard et al., Reference Baumgard, Rhoads, Rhoads, Gabler, Ross, Keating, Boddicker, Lenka and Sejian2012). Global demand for livestock products is expected to double during the first half of this century, due to human population growth and increasing affluence. However, it is important to note that the net impact of climate change depends not only on the extent of the climatic shock but also on underlying vulnerabilities. According to Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2016), both biophysical and social vulnerabilities determine the net impact of climate change on food security. Therefore, reducing the risks to food security from climate change is one of the major challenges of the 21st century.

Climate change and the concept of multiple stresses impacting livestock

Livestock in hot semi-arid environments are for the most part reared in extensive systems. The productive potential of livestock in these areas is influenced by their exposure to harsh climatic factors. Climate changes could increase thermal stress for animals and thereby reduce their production and profitability by lowering feed efficiency, growth rates and reproduction rates. Furthermore, heat stress is not the only stressor that livestock are exposed to as a result of climate change. Livestock grazing in hot semi-arid zones are confronted with large variations in the quantity and quality of feed and water on offer throughout the year. In addition, animals often have to walk long distances in search of these limited resources during hot summer months. Grazing animals are therefore potentially exposed to multiple stressors: heat stress, feed and water scarcity, and physical stress due to walking in hot semi-arid environments (Sejian et al., Reference Sejian, Maurya, Kumar and Naqvi2013). The reality is that these stressors occur simultaneously rather than individually in extensive grazing systems. Therefore, from a climate change perspective, it is essential to study the influence of all the major environmental stressors simultaneously in order to understand in depth the adaptive capability of the target species. A hypothetical model for the concept of multiple stressors in sheep is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2 Description of hypothetical model of concept of multiple stresses affecting livestock production. This figure is depicted in three different parts: thermo-neutral condition, single stress and stress summation. The first part describes the normal functions in sheep under thermo-neutral condition depicting the basal functions, which are vital for their survival in any adverse condition, and productive functions which include growth, reproduction, milk production, meat production and immunity. Apart from this, the first part of the figure also describes the body reserves that the animals possess which could be used for supporting the adaptive functions during exposure to adverse environmental conditions. The second part of the figure depicts the events that take place when the animals are subjected to single stress. This part of figure describes the mechanism by which the animal copes to single stress exposure based on its body reserves keeping intact all its productive functions. The third part of the figure depicts the various events that take place in animals on exposure to two or more stress. In this particular condition of summated stress, the animal’s body reserves are not sufficient to cope with two stresses and therefore it has to compromise one of its productive functions (growth in this case) to support the adaptive pathway requirement. Thus, it could be inferred that when the animals are subjected to single stress the animals can counter that with the help of their body reserves. However, when two or more stresses occur simultaneously then the total impact may be severe in the animals that the body reserves are not sufficient to cope them to the cumulative stress impact and therefore animals have to compromise one of its productive functions to cope with the existing situation.

In a study conducted on Malpura rams, multiple stressors exposure significantly reduced both BW and body condition score (BCS) (Kumar et al., Reference Kumar, Sejian, Gaughan and Naqvi2017). A similar finding of reduced BW when subjected to two and three simultaneous environmental stressors has been established for Malpura ewes (Sejian et al., Reference Sejian, Maurya, Kumar and Naqvi2013). This emphasizes that proper nutrition during thermal stress is important in the maintenance of normal BW; the challenge, however, is how to maintain feed intake during periods of heat stress. The reduced BCS in multiple stressor rams could be attributed to the depletion of body reserves.

Significance of identifying climate resilient animals

One step towards food security is to have breeds which can cope with adversities of climate change. Indigenous livestock breeds in many developing countries, in contrast to European breeds (exotic), are portrayed as being the hardiest breeds, being able to cope and produce in harsh environments due to physiological and genetic adaptations (Rojas-Downing et al., Reference Rojas-Downing, Nejadhashem, Harrigan and Woznicki2017). Although their production potential is less compared with exotic and cross breeds, their level of production is relatively stable during testing conditions where high producing animals succumb. Further during periods of extreme heat stress, water scarcity and reduced pasture availability, indigenous breeds maintain their reproductive potential due to their smaller body size whereas the larger exotic animals may face reproductive impairments which could be attributed to their higher energy requirements. In a heat stress experiment conducted using three indigenous goat breeds from different agro-ecological zones, the Salem Black breed was identified as the superior adaptive breed when compared with the Osmanabadi and the Malabari breeds when all were assessed at the same location (Pragna et al., Reference Pragna, Sejian, Soren, Bagath, Krishnan, Beena, Devi and Bhatta2018). The authors attributed this to the test locations being less stressful than the Salem Blacks’ original location. Breeding strategies must ensure the development of appropriate agro-climatic zone specific livestock breeds which possess superior thermo-tolerance, drought tolerance and the ability to survive in limited pastures. Hence, it is necessary to test the relevant species under climatic conditions that they will likely be exposed to.

Different mechanisms of livestock adaptation

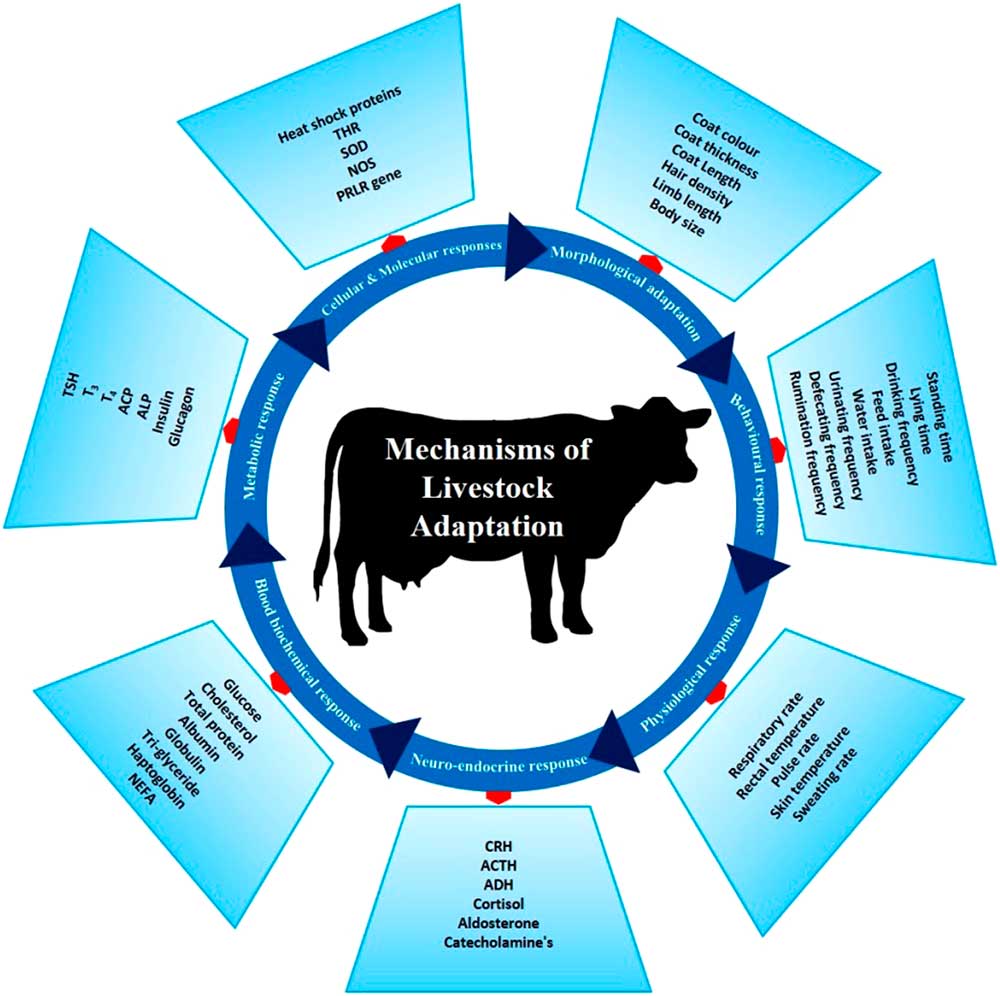

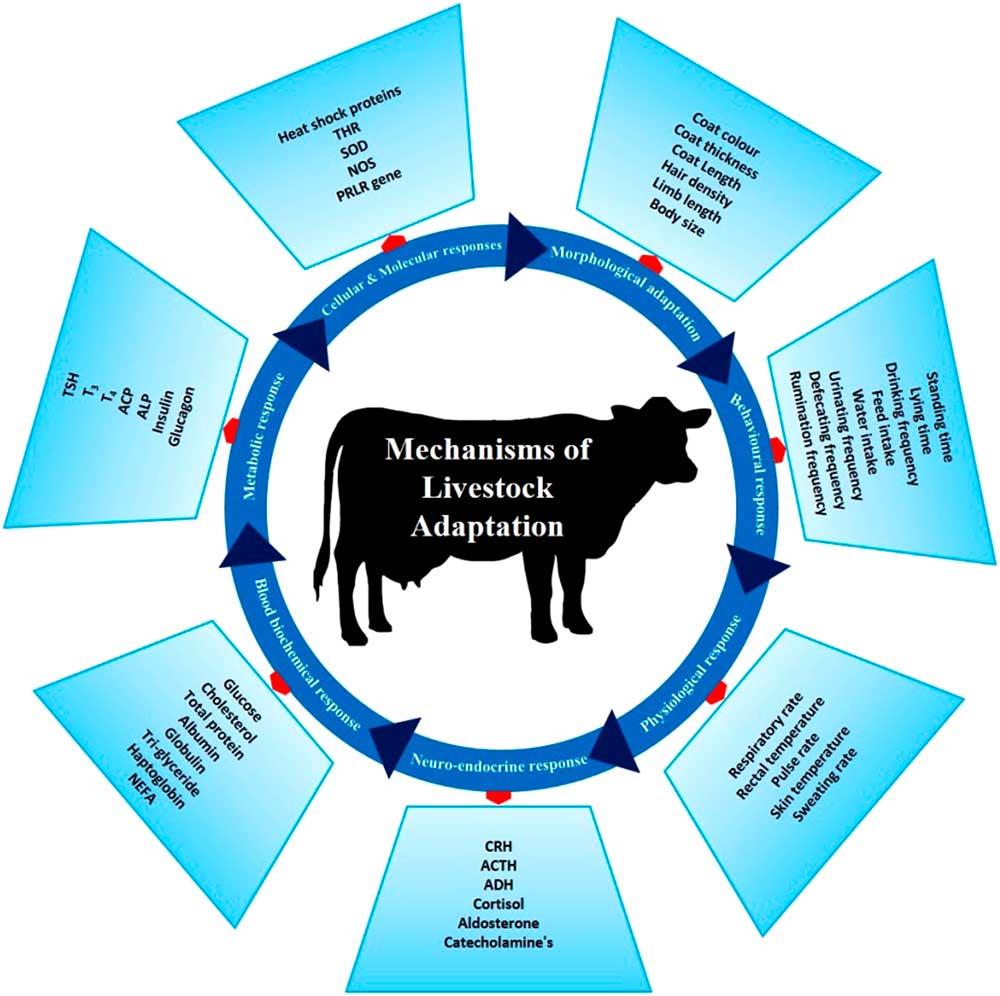

There are several phenotypic and genotypic characters which impart the adaptive potential to an animal, thereby allowing it to cope with harsh conditions. These adaptive mechanisms help animals survive in a particular environment (Figure 3). Basically, animal adaptation involves morphological, behavioural and genetic capacity of the animal for change. These may arise over generations through slow modifications as animals adapt to environmental challenges. The adaptive process can be expanded to include (i) morphological, (ii) behavioural, (iii) physiological, (iv) neuro-endocrine, (v) blood biochemistry, (vi) metabolic, (vii) molecular and (viii) cellular responses which combine to promote survival in a specific environment.

Figure 3 Different adaptive mechanisms of livestock to cope to the harsh climatic condition. These mechanisms help the animals to survive the heat stress challenges. THR=thyroid hormone receptor; SOD=super oxide dismutase; NOS=nitrous oxide synthase; PRLR=prolactin receptor; CRH=corticotropin-releasing hormone; ACTH=adrenocoticotropic hormone; ADH=antidiuretic hormone; NEFA=non-esterified fatty acids; TSH=thyroid-stimulating hormone; T3=triiodothyronine; T4=thyroxine; ACP=acid phosphatase; ALP=alkaline phosphatase.

Morphological response

Morphological traits in livestock are highly important from the adaptation point of view, as they directly influence the heat exchange mechanisms (cutaneous convection, radiation and evaporation) between the animal and the surrounding environment (McManus et al., Reference McManus, Paludo, Louvandini, Gugel, Sasaki and Paiva2009). Breed differences for morphological adaptive traits are evident in some species (McManus et al., Reference McManus, Paludo, Louvandini, Gugel, Sasaki and Paiva2009). Coat colour was one of the important morphological traits which imparts adaptive ability to heat stressed livestock (Figure 3). For example, light-/white-coloured coats in animals are recognized as being advantageous in hot tropical regions as it reflects 50% to 60% of direct solar radiation compared with the dark-coloured animals (McManus et al., Reference McManus, Paludo, Louvandini, Gugel, Sasaki and Paiva2009). Highly pigmented skin protects the deep tissues from direct short wave UV radiation by blocking its penetration. In addition, coat length, thickness and hair density also affect the adaptive nature of animals in tropical regions, where short hair, thin skin and fewer hair follicles per unit area are directly linked to higher adaptability to hot conditions (Figure 3). Indigenous sheep breeds adapted to arid and semi-arid regions possess morphological characteristics such as carpet type wool, which helps to provide better protection from direct solar radiation, and this type of wool also allows effective cutaneous evaporative heat dissipation (Mahgoub et al., Reference Mahgoub, Kadim, Al-Dhahab, Bello, Al-Amri, Ali and Khalaf2010). The fat tail observed in sheep is also recognized as a morphological adaptation for better heat transfer (Gootwine, Reference Gootwine2011).

Cutaneous evaporation is recognized as the most important mode of heat dissipation in cattle. Thus, higher diameter, volume, perimeter and density of sweat gland in animals are considered to be good adaptive traits for hot environments (Jian et al., Reference Jian, Ke and Cheng2016). Smaller body size of tropical indigenous cattle breeds (as compared with English and European cattle) is recognized as being beneficial for surviving in harsh environments, due in part to the smaller animals’ lower feed and water requirements (Figure 3). In addition, cattle breeds that are indigenous to the tropical regions also possess efficient testicular thermoregulatory mechanisms during heat stress conditions through higher ratios of testicular artery length and volume to the volume of testicular tissue (Brito et al., Reference Brito, Silva, Barbosa and Kastelic2004).

Behavioural response

Behavioural adaptation is recognized as the first and foremost response adopted by animals to reduce heat load (Shilja et al., Reference Shilja, Sejian, Bagath, Mech, David, Kurien, Varma and Bhatta2016). One of the most quick and profound behavioural changes seen in heat stressed animals is shade seeking. The stressed animals attempt to ameliorate the negative effects of direct heat load by using shade whenever they can access to it. Research clearly shows that dairy cattle use shade in warm environments, and that the frequency of this behaviour was found to increase with higher air temperature and solar radiation (Curtis et al., Reference Curtis, Scharf, Eichen and Spiers2017). However, tropical indigenous breeds were observed to be highly adapted to direct heat stress, spending more time for grazing than resting in shade.

Another important and well-documented behavioural response to enhanced heat load loss in ruminants is reduced feed intake (Figure 3). Recent studies established lower feed intake in various farm animals including cattle, sheep and goats during summer (Lacetera et al., Reference Lacetera, Bernabucci, Ronchi and Nardone1996; Spiers et al., Reference Spiers, Spain, Sampson and Rhoads2004; Shilja et al., Reference Shilja, Sejian, Bagath, Mech, David, Kurien, Varma and Bhatta2016). Lower feed intake in warm conditions is identified as an adaptive response to regulate the internal metabolic heat production in heat stressed animals (Figure 3). Similarly, Valente et al. (Reference Valente, Chizzotti, Oliveira, Galvão, Domingues, Rodrigues and Ladeira2015) reported reduced feed intake in both heat stressed Nellore and Angus cattle breeds as compared to their counterparts kept in normal controlled condition. In addition, behavioural studies also showed changes in grazing patterns of extensively managed cows with low and high grazing time during day and night, respectively (Curtis et al., Reference Curtis, Scharf, Eichen and Spiers2017).

Higher drinking frequency (Figure 3) and increased water intake were reported for various livestock species during summer (Valente et al., Reference Valente, Chizzotti, Oliveira, Galvão, Domingues, Rodrigues and Ladeira2015; Shilja et al., Reference Shilja, Sejian, Bagath, Mech, David, Kurien, Varma and Bhatta2016). Breeds adapted to desert regions compensate higher water loss during periods of high heat load by concentrating urine (Chedid et al., Reference Chedid, Jaber, Giger-Reverdin, Duvaux-Ponter and Hamadeh2014).

Increased standing and decreased lying time was also reported to be associated with higher ambient temperatures (Silanikove, Reference Silanikove2000; Darcan et al., Reference Darcan, Cedden and Cankaya2008; Provolo and Riva, Reference Provolo and Riva2009). Generally, heat stressed animals tend to spend more time standing so that they can reorient themselves in different directions to avoid direct solar radiation and ground radiation (Figure 3). In addition, the standing position also obstructs the conductive heat transfer into the animal body due to the presence of a layer of air adjacent to the skin, and also facilitates the dissipation of body heat load to the surroundings by increasing the amount of skin exposed to air flow or wind. However, indigenous Osmanabadi bucks did not show any significant variation for standing time, lying time and urinating frequency, when they were exposed to summer heat stress, indicating their adaptation to hot conditions (Shilja et al., Reference Shilja, Sejian, Bagath, Mech, David, Kurien, Varma and Bhatta2016).

Physiological response

Physiologically, ruminants adapt to high heat load through enhanced respiratory and sweating rates (Silanikove, Reference Silanikove2000; Marai et al., Reference Marai, El-Darawany, Fadiel and Abdel-Hafez2007). Usually, higher respiration rate (RR) and sweating rates are observed when animals are exposed to increasing environmental heat (Figure 3). The respiratory and cutaneous cooling mechanisms directly involve dissipation of the extra heat load in the body by vaporizing more moisture to the surroundings (Carvalho et al., Reference Carvalho, Lammoglia, Simoes and Randel1995; Kadzere et al., 2002; Berman, Reference Berman2006). An increase in RR was reported in various cattle breeds including Angus, Nellore and Sahiwal when they were exposed to high heat load (Valente et al., Reference Valente, Chizzotti, Oliveira, Galvão, Domingues, Rodrigues and Ladeira2015). This shows that even cattle adapted to hot conditions (e.g. Sahiwal) will show a response to increased environmental heat load. Leite et al. (Reference Leite, Façanha, Costa, Chaves, Guilhermino, Silva and Bermejo2018) reported greater adaptability of Morada Nova ewes (acclimatized to Brazilian conditions) to hot arid conditions. The ewes were able to maintain normal RR at an ambient temperature of 32°C. An increase in pulse rate (PR) and rectal temperature (RT) were also reported in farm animals during summer (Shilja et al., Reference Shilja, Sejian, Bagath, Mech, David, Kurien, Varma and Bhatta2016). In addition to this, the greater RT during summer also confirms the inability of these farm animals to maintain normal body temperature (Figure 3). Daily examination of the indigenous zebu breeds (Gir, Sindhi and Indubrasil) also showed higher magnitude for physiological parameters such as RT and heart rate during afternoon (35.9°C) (Cardoso et al., Reference Cardoso, Peripolli, Amador, Brandão, Esteves, Sousa and Martins2015). Similar to this, sheep breeds reared in the Indian semi-arid regions also showed higher PR and RT where the average temperature and humidity during the day was 33.7°C and 54.9%, respectively (Rathwa et al., Reference Rathwa, Vasava, Pathan, Madhira, Patel and Pande2017). The higher PR enables the stressed animals to dissipate more heat to its surroundings by increasing the blood flow to their body surfaces (Shilja et al., Reference Shilja, Sejian, Bagath, Mech, David, Kurien, Varma and Bhatta2016). Likewise, Osmanabadi goats evolved in the Indian semi-arid regions also showed adaptability to heat stress, nutritional stress and combined stress (heat stress+ nutritional stress) conditions (temperature, 40°C; humidity, 55%) by altering their physiological variables (Shilja et al., Reference Shilja, Sejian, Bagath, Mech, David, Kurien, Varma and Bhatta2016). Further, exposure of ruminants to hot environment also increased skin temperature (ST) (Figure 3). Examination of both Nguni and Boran cattle breeds showed higher ST during summer (Katiyatiya et al., Reference Katiyatiya, Bradley and Muchenje2017). Higher ST was also recorded in Osmanabadi goats during summer (Shilja et al., Reference Shilja, Sejian, Bagath, Mech, David, Kurien, Varma and Bhatta2016). This higher ST could be directly attributed to the vasodilatation of skin capillary bed to enhance the blood flow to the skin periphery for facilitating heat transfer to the surroundings (Shilja et al., Reference Shilja, Sejian, Bagath, Mech, David, Kurien, Varma and Bhatta2016).

Similarly, in a recent study using Malpura rams, Sejian et al. (Reference Sejian, Kumar and Naqvi2017) reported significantly lower feed intake and higher water intake in sheep exposed to multiple stressors. Further, significantly higher RR and RT in the multiple stress group were reported in the same study (Sejian et al., Reference Sejian, Kumar and Naqvi2017). In addition, ST and scrotal temperature were significantly higher in the multiple stresses group. It is postulated from these findings that these parameters could be useful biomarkers of the adaptive capacity of Malpura rams. It was observed that scrotal temperature was a better indicator than ST in assessing the impact of multiple stressors (Sejian et al., Reference Sejian, Kumar and Naqvi2017). The observed differences between scrotal and STs could be attributed to the amount of wool on the body as compared with scrotum. Furthermore, the scrotum is an important thermoregulatory organ in sheep. Hence, scrotal temperature has higher significance for assessing the thermo-tolerant capability of sheep. In a similar study in Osmanabadi goats, Shilja et al. (Reference Shilja, Sejian, Bagath, Mech, David, Kurien, Varma and Bhatta2016) also reported that RR, RT and ST to be reliable indicators of multiple stressors in goats.

Neuro-endocrine response

Hormones, specifically those produced from the adrenal and thyroid glands, are recognized as having a significant role in thermoregulation and metabolic adjustments in animals, particularly in hot environments. The hypothalamo–pituitary–adrenal axis (HPA axis) acts as one of the principal endocrine regulators of the stress responses. The products of HPA axis which control stress pathway in animals are corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), ACTH and cortisol (Figure 3). The activation of the HPA axis may lead to enhanced production and release of cortisol into circulation; cortisol is the primary stress hormone of ruminants (Binsiya et al., 2017). Several studies of various livestock species clearly established higher plasma cortisol level in ruminants during heat stressed conditions (Wojtas et al., 2014; Marina and von Keyserlingk, 2017). Further, the plasma aldosterone level in heat stressed Osmanabadi goats was reported to be higher as compared with the normal conditions and when they had ad libitum water access (Shilja et al., 2017). Aldosterone is a steroid hormone released from the cortex of the adrenal glands and is involved in the regulation of water and mineral balance in the body. It is a well-established fact that during heat stress conditions ruminants may undergo severe dehydration, which may result in the activation of renin–angiotensin–aldosterone pathway to restore the water and electrolyte balance.

In a similar study in Malpura rams, Sejian et al. (Reference Sejian, Kumar and Naqvi2017) reported that the plasma cortisol level was significantly lower in multiple stressors groups (heat, nutrition and walking) as compared with individual (heat stress/nutritional stress) or combined stresses (heat and nutrition stress) (Sejian et al., Reference Sejian, Maurya, Kumar and Naqvi2013). This was in contrast to the findings of Shilja et al. (Reference Shilja, Sejian, Bagath, Mech, David, Kurien, Varma and Bhatta2016) using Osmanabadi goats wherein they reported significantly higher plasma cortisol concentration in multiple stresses (heat and nutritional stress) group as compared with the individual stress (heat/nutrition) group. This suggests that goats are better able to cope with the multiple stressors than sheep.

Severe dehydration may lead to increased secretion of antidiuretic hormone (ADH) through activation of renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (Figure 3). Higher levels of circulating ADH hormone level were reported in crossbred goats under severe dehydration (Kaliber et al., Reference Kaliber, Koluman and Silanikove2016). The ADH hormone regulates the blood osmolarity by increasing the water absorption in the kidneys, which also assists the excretion of concentrated urine in animals suffering from heat stress (Kaliber et al., Reference Kaliber, Koluman and Silanikove2016). Further, sympathetic adrenal medullary system also contributes enormously for controlling stress activities primarily through the release of catecholamines in animals (Figure 3).

Blood biochemical response

There are several reports which showed a varying trend of total blood haemoglobin (Hb) with an increase in environmental temperature. Haque et al. (Reference Haque, Ludri, Hossain and Ashutosh2013) observed a significant rise in total blood Hb concentration at 40°C, 42°C and 45°C as compared with 22°C in both young and adult heat stressed Murrah buffaloes. They attributed this increase to haemoconcentration so that the animals could meet a higher oxygen requirement during stressful conditions. An elevated value of Hb was also established in thermal stressed southern Nigeria dwarf goats and the observed change may be attributed to higher Hb requirement in the animal to meet the increased oxygen circulation during panting (Okoruwa, Reference Okoruwa2014). A higher value of total blood Hb concentration was also observed in lactating Surti buffaloes during a hot dry period compared with a hot humid period, and that the increased Hb was correlated to severe dehydration (Chaudhary et al., Reference Chaudhary, Singh, Upadhyay, Puri, Odedara and Patel2015).

Plasma haptoglobin has been observed to rise in dairy cows during high ambient temperatures (Alberghina et al., Reference Alberghina, Piccione, Casella, Panzera, Morgante and Gianesella2013). Haptoglobin is one of the most commonly used acute phase proteins to assess the health and inflammatory response of animals (Aleena et al., Reference Aleena, Pragna, Archana, Sejian, Bagath, Krishnan, Manimaran, Beena, Kurien, Varma and Bhatta2016). Alberghina et al. (Reference Alberghina, Piccione, Casella, Panzera, Morgante and Gianesella2013) reported a significantly higher production of haptoglobin in the blood plasma of Holstein-Frisian dairy cows exposed to high heat load.

In several experiments, significantly increased levels of packed cell volume (PCV) were observed in various livestock species suffering from heat stress (McManus et al., Reference McManus, Paludo, Louvandini, Gugel, Sasaki and Paiva2009; Rana et al., Reference Rana, Hashem, Sakib and Kumar2014). However, a decreased concentration of plasma protein (Khalek, Reference Khalek2007; Hooda and Upadhyay, Reference Hooda and Upadhyay2014) and cholesterol (Hooda and Upadhyay, Reference Hooda and Upadhyay2014) were recorded in livestock exposed to elevated ambient temperatures (Figure 3). Further, there are reports which also established an increased concentration of free fatty acid in livestock exposed to heat stress (Chaiyabutr et al., Reference Chaiyabutr, Boonsanit and Chanpongsang2011).

Antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD) and glutathione peroxidase (GPx) are synthesized in the body and provide protection from reactive oxygen species generated during heat stress (Gupta et al., Reference Gupta, Kumar, Dangi and Jangir2013). These antioxidants scavenge both intracellular and extracellular super oxides and inhibit lipid peroxidation of plasma membrane (Zhang, et al., Reference Zhang, Yin, Huang, Wang, Gong, Liu and Sun2017). Chaudhary et al. (Reference Chaudhary, Singh, Upadhyay, Puri, Odedara and Patel2015) reported a significantly higher level of plasma malondialdehyde, SOD and GPx activities in Surti buffaloes during hot humid periods and hot dry periods indicating an increased free radical production during periods of heat stress. In addition to this, plasma antioxidant levels in the hot dry period were significantly higher than in the hot humid period indicating more stressful condition may lead to the elevated synthesis of free radicals (Chaudhary et al., Reference Chaudhary, Singh, Upadhyay, Puri, Odedara and Patel2015). Likewise, Kumar et al. (Reference Kumar, Singh and Meur2010) also reported a significant increase in SOD activity in Beetal goats during summer. However, in order to examine the whole body defence mechanism, total antioxidant status (TAS) is preferred. There are also reports establishing significantly higher TAS values in a hot dry season in ruminant animals (Chaiyabutr et al., Reference Chaiyabutr, Boonsanit and Chanpongsang2011; Chaudhary et al., Reference Chaudhary, Singh, Upadhyay, Puri, Odedara and Patel2015). All these findings establish the significance of blood biochemical responses to be one of the primary means used by animals to cope with adverse environmental conditions.

Metabolic responses

Metabolic adaptation is considered to be one of the important means through which animals tackle heat stress challenges, essentially by reducing the metabolic heat production (Pragna et al., Reference Pragna, Sejian, Soren, Bagath, Krishnan, Beena, Devi and Bhatta2018). Thyroid hormones play an important role in regulating the thermogenesis and are also identified as an indicator for assessing the thermo-tolerance of the farm animals (Todini, Reference Todini2007). Thyroid hormones, namely triiodothyronine (T3) and thyroxine (T4), play a vital role in metabolic adaptation and growth performance of animals (Aleena et al., Reference Aleena, Pragna, Archana, Sejian, Bagath, Krishnan, Manimaran, Beena, Kurien, Varma and Bhatta2016). During heat stress, serum and plasma concentrations of T3 and T4 reduce and are likely to be due to the direct effect of heat stress on the hypothalamo pituitary and thyroid axis to decrease the production of thyrotropin-releasing hormone, which will limit basal metabolism (Pragna et al., Reference Pragna, Sejian, Soren, Bagath, Krishnan, Beena, Devi and Bhatta2018). In a recent study conducted using three indigenous goat breeds during summer, it was concluded that T3 could serve as an indicator of metabolic activity in animals (Pragna et al., Reference Pragna, Sejian, Soren, Bagath, Krishnan, Beena, Devi and Bhatta2018). Reduced concentrations of circulating T3 and T4, indicative of an attempt to reduce metabolic rate and thus metabolic heat production in heifers (Pereira et al., Reference Pereira, Baccari, Titto and Almeida2008), sheep (Indu et al., Reference Indu, Sejian, Kumar, Pareek and SMK2015) and goat (Todini, Reference Todini2007), have been reported. However, contrary results showing no significant alterations in the metabolic hormonal levels have also been reported recently in three indigenous breeds of goats (Pragna et al., Reference Pragna, Sejian, Soren, Bagath, Krishnan, Beena, Devi and Bhatta2018). The authors suggest that this is due to the superior adaptive capability of the animals to the hot tropical climate. On comparative basis, the effect of multiple stressors on plasma T3 and T4 was not severe in Osmanabadi goats as only T4 differed between the control and multiple stress groups; whereas in the sheep study, the severity of multiple stresses were of higher magnitude on plasma thyroid hormone levels with much lower levels of both T3 and T4 concentration (Sejian et al., Reference Sejian, Maurya, Kumar and Naqvi2013). This again points towards the better adaptive mechanisms in goats as compared with sheep at least for multiple stressor exposure.

During periods of high ambient temperatures, some metabolic enzymes increase their activity, the levels of activity of these enzymes in plasma can be informative of how various organs are responding and adapting to heat load and such enzymes play a vital role in the diagnosis of welfare of animals (Gupta et al., Reference Gupta, Kumar, Dangi and Jangir2013). Acid phosphatase and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) are two major enzymes associated with the metabolic activities in animals (Figure 3). The levels of these enzymes are generally low in heat stressed animals, which could be attributed to a metabolic shift in the animals (Gupta et al., Reference Gupta, Kumar, Dangi and Jangir2013). Likewise, Hooda and Singh (Reference Hooda and Singh2010) reported a decrease in ALP during summer in buffalo heifers, which they attributed to the dysfunction of the liver during heat stress exposure. Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase are two important metabolic enzymes that increase during heat stress exposure in sheep (Nazifi et al., Reference Nazifi, Saeb, Rowghani and Kaveh2003) and goats (Gupta et al., Reference Gupta, Kumar, Dangi and Jangir2013). These authors attributed such increase in the activity of these enzymes to the higher adaptive capability of the animals to cope with heat stress (Banerjee et al., Reference Banerjee, Upadhyay, Chaudhary, Kumar, Singh, Ashutosh, Das and De2015). However, in a recent study conducted using indigenous Osmanabadi goats, AST activity was observed to increase significantly only when heat stress condition was coupled with nutritional stress. This highlights the importance of the combined effect of the stressors on metabolic responses (Shilja et al., Reference Shilja, Sejian, Bagath, Mech, David, Kurien, Varma and Bhatta2016). However, in contrast, there was no significant influence of heat stress on AST in goats has been reported (Sharma and Kataria, Reference Sharma and Kataria2011).

Another important metabolic regulator is non-esterified fatty acids (NEFA) in plasma and serum (Aleena et al., Reference Aleena, Pragna, Archana, Sejian, Bagath, Krishnan, Manimaran, Beena, Kurien, Varma and Bhatta2016). Low NEFA concentrations are mostly reported in heat stressed dairy cows. It is thought that this is an attempt to increase glucose utilization which will result in lower metabolic heat production (Rhoads et al., Reference Rhoads, Rhoads, VanBaale, Collier, Sanders, Weber, Crooker and Baumgard2009; Baumgard and Rhoads, Reference Baumgard and Rhoads2012). However, Shehab-El-Deen et al. (Reference Shehab-El-Deen, Leroy, Fadel, Saleh, Maes and Van Soom2010) reported an increase in NEFA production of dairy cows during summer compared with winter, which they attributed to an attempt by the animals to maintain energy balance.

In summary, at least in livestock, haptoglobin, NEFA, T3 and T4 are considered to be reliable indicators of metabolic adaptation to high heat load (Aleena et al., Reference Aleena, Pragna, Archana, Sejian, Bagath, Krishnan, Manimaran, Beena, Kurien, Varma and Bhatta2016).

Cellular and molecular responses

Heat stress was found to alter several molecular functions such as DNA synthesis, replication and repair, cellular division and nuclear enzymes and DNA polymerases functions (Higashikubo et al., Reference Higashikubo, White and Roti Roti1993; Slimen et al., Reference Slimen, Najar, Ghram and Abdrrabba2016). Further, it was shown that heat stress affects both the fluidity and the stability of cellular membranes and inhibits receptors as well as transmembrane transport proteins function (Slimen et al., Reference Slimen, Najar, Ghram and Abdrrabba2016). Heat stress also induces multiple variations in cytoskeleton organization, including the cell form, the mitotic apparatus and the intracytoplasmic membranes such as endoplasmic reticulum and lysosomes.

Heat stress elicits a complex array of cellular and molecular responses in livestock (Hao et al., Reference Hao, Feng, Yang, Cui, Liu, Yang and Gu2016). With the development of molecular biotechnologies, new opportunities are available to characterize gene expression and identify key cellular responses to heat stress (Renaudeau et al., Reference Renaudeau, Collin, Yahav, de Basilio, Gourdine and Collier2012). For example, there are changes in the expression patterns of certain genes that are fundamental for thermo-tolerance at the cellular level in animals (Gupta et al., Reference Gupta, Kumar, Dangi and Jangir2013). Such genes having a cellular adaptation function in animals are considered potential biomarkers for understanding stress adaptation mechanisms (Collier et al., Reference Collier, Gebremedhin, Macko and Roy2012). The classical heat shock protein (HSP) genes, apoptotic genes and other cytokines and toll-like receptors are considered to be up regulated on exposure to heat stress. Several reports established the role of HSP70 during heat stress exposure in ruminant livestock and they identified this to be ideal molecular marker for quantifying heat stress response (Collier et al., Reference Collier, Gebremedhin, Macko and Roy2012; Gupta et al., Reference Gupta, Kumar, Dangi and Jangir2013; Shilja et al., Reference Shilja, Sejian, Bagath, Mech, David, Kurien, Varma and Bhatta2016). Apart from this, several other genes such as SOD, nitric oxide synthase (NOS), thyroid hormone receptor (THR) and prolactin receptor (PRLR) genes were found to be associated with thermo-tolerance in ruminant livestock (Collier et al., Reference Collier, Gebremedhin, Macko and Roy2012).

Furthermore, Shilja et al. (Reference Shilja, Sejian, Bagath, Mech, David, Kurien, Varma and Bhatta2016) reported a higher expression of HSP70 messenger RNA (mRNA) in the adrenal gland of the multiple stressor groups, which could be attributed to the adaptive mechanism of Osmanabadi goats to counter both the heat stress and nutritional stress. The significantly higher expression of adrenal HSP70 in the multiple stressed animals as compared with animals subjected only to heat stress could be attributed to additional nutritional stress in the multiple stresses group. The higher HSP70 expression in the adrenal gland could also be attributed to the hyperactivity of adrenal cortex to synthesize more cortisol as evident from this study (Shilja et al., Reference Shilja, Sejian, Bagath, Mech, David, Kurien, Varma and Bhatta2016). Similarly, the plasma HSP70 and expression pattern of peripheral blood mononuclear cell HSP70 also showed similar trends of significantly higher value in multiple stressor group animals as compared with control and individual (heat/nutritional) stress groups (Shilja et al., Reference Shilja, Sejian, Bagath, Mech, David, Kurien, Varma and Bhatta2016).

Epigenetic regulation of gene expression and thermal imprinting of the genome could also be an efficient method to improve thermal tolerance in livestock (Renaudeau et al., Reference Renaudeau, Collin, Yahav, de Basilio, Gourdine and Collier2012). At the molecular level, epigenetic changes are mediated by changes to the chromatin conformation initiated by DNA methylation, histone variants, post-translational modifications of histones and histone inactivation, non-histone chromatin proteins, non-coding RNA and RNA interference (Scholtz et al., Reference Scholtz, van Zyl and Theunissen2014). Deoxyribonucleic acid methylation is a well-studied epigenetic regulatory mechanism that plays a key role in the regulation of gene expression. Heat stress was found to influence the DNA methylation pattern in pigs (Hao et al., Reference Hao, Feng, Yang, Cui, Liu, Yang and Gu2016). Further, these authors also established that HSP70s and their associated cochaperones participate in numerous processes essential to cell survival under stressful conditions. They assist in protein folding and translocation across membranes, assembly and disassembly of protein complexes, presentation of substrates for degradation and suppression of protein aggregation (Hao et al., Reference Hao, Feng, Yang, Cui, Liu, Yang and Gu2016). The above discussion clearly point towards the influence of both the genetic and epigenetic changes altering the thermo-tolerant gene expression and therefore, both these factors should be taken into account when formulating breeding programmes for changing environmental conditions.

Advances in assessing the thermo-tolerant ability of livestock

An animal performs optimally under thermo-neutral conditions. However, an increase or decrease in the atmospheric temperature outside of the thermoneutral zone reduces the performance and adaptability of animals. Environmental factors such as ambient temperature, relative humidity, solar radiation and wind speed play a crucial role in regulating the performance of animals. With advancements in the scientific technologies, researchers have developed a plethora of animal comfort or stress assessment tools. Various temperature assessment devices such as rumen temperature measurement devices and IR thermometer and thermal indices, for example temperature–humidity index (THI), heat load index (HLI), black globe-humidity index, equivalent temperature index, respiratory rate predictor and environmental stress index, are commonly used to measure thermo-adaptability of animals.

Temperature humidity index

The THI is generally considered as the most reliable stress indicator for animals. The THI was first used to assess the severity of heat stress in the dairy animals. The THI can be used as a forecast system to assess the possible threat or danger to the animals due to climatic variations. Currently, there are several THI indices that are in use to assess the quantum of heat stress in animals. However, THI has two drawbacks as it does not take into account solar radiation and wind speed, which are also considered important cardinal weather parameters, greatly influencing the animal response to heat stress challenges. This has brought the drive in the scientific community to develop advanced thermal indices to address these drawbacks of THI indices.

Heat load index

Heat load index is developed as an improvement which overcomes the perceived deficiencies in the THI index. It uses a combination of black globe temperature, air movement and relative humidity. The HLI uses two equations based on the threshold value of black globe thermometer (Gaughan et al., Reference Gaughan, Mader, Holt and Lisle2008):

$$\eqalignno{ & {\rm HLI}\,{\rm BG}\geq 25{\equals}8.62{\plus}\left( {0.38{\times}{\rm RH}} \right)\cr \quad \quad \quad \quad \quad \quad {\plus}\left( {1.55{\times}{\rm BG}} \right){\minus}\left( {0.5{\times}{\rm WS}} \right){\plus}{\rm e}^{{(2.4{\minus}{\rm WS})}} \cr & {\rm HLI}\,{\rm BG}\,\lt\,25{\equals}10.66{\plus}\left( {0.28{\times}{\rm RH}} \right){\plus}\left( {1.3{\times}{\rm BG}} \right){\minus}{\rm WS,} $$

$$\eqalignno{ & {\rm HLI}\,{\rm BG}\geq 25{\equals}8.62{\plus}\left( {0.38{\times}{\rm RH}} \right)\cr \quad \quad \quad \quad \quad \quad {\plus}\left( {1.55{\times}{\rm BG}} \right){\minus}\left( {0.5{\times}{\rm WS}} \right){\plus}{\rm e}^{{(2.4{\minus}{\rm WS})}} \cr & {\rm HLI}\,{\rm BG}\,\lt\,25{\equals}10.66{\plus}\left( {0.28{\times}{\rm RH}} \right){\plus}\left( {1.3{\times}{\rm BG}} \right){\minus}{\rm WS,} $$

where BG is the black globe temperature in °C, RH the relative humidity in %, WS the wind speed in m/s and e the exponential. The HLI is an ideal indicator of the temperature status of the animal and it can explain 93% of the alterations in panting score (Gaughan et al., Reference Gaughan, Mader, Holt and Lisle2008). Further, the HLI considers the variation in the genotype whereas THI index does not.

Infrared thermometer

Body temperature measurement can be a reliable indicator of heat stress and thermal balance in animals. However, traditional methods of measuring body temperature involve relocating animals to specifically designed handling facilities. Relocation of animals may result in an increase in body temperature, potentially masking illness and disrupting the thermal balance. Hence, the farming community are in search for an alternate non-invasive method which can reflect the actual stress level of the animals. To overcome all these difficulties, advanced temperature measurement techniques like IR thermometers are used in place with conventional contact temperature measuring devices.

Infrared thermography is a non-invasive measurement of body surface temperature. Infrared thermography measures the IR radiation emitted from an animal, which then allows for the determination of body surface temperature. Due to increasing animal welfare concerns, non-invasive methods of obtaining body temperature that is fast, efficient and reliable need to be investigated. Recently, there have been studies to investigate the use of IR thermography as a measure of body temperature (Lees et al., Reference Lees, Lees, Sejian, Wallage and Gaughan2018). Furthermore, there have been some studies utilizing IR thermography to determine the thermal balance in poultry, pigs, cattle and wildlife (Ferreira et al., Reference Ferreira, Francisco, Belloni, Aguirre, Caldara, Nääs, Garcia, Almeida Paz and Polycarpo2011; Naas et al., Reference Naas, Garcia and Caldara2014; Lees et al., Reference Lees, Lees, Sejian, Wallage and Gaughan2018).

Rumen temperature measurement

Rumen temperature measurement is a useful technique to assess variation in the physiological responses of runimantes to heat load exposure. Currently, there are manifold technologies available in measuring rumen temperature for adaptation studies (Boehmer et al., Reference Boehmer, Pye and Wettemann2015). Advanced rumen temperature measurements such as rumen boluses are ideal for adaptation studies as they can give continuous rumen temperature measurements in real time (telemetry) without disturbing the animal (Lohölter et al., Reference Lohölter, Rehage, Meyer, Lebzien, Rehage and Dänicke2013; Lees et al., Reference Lees, Lees, Sejian, Wallage and Gaughan2018).

Biological markers for quantifying heat stress response in livestock

There are both phenotypic and genotypic trait markers available to quantify the heat stress responses in livestock. Traditionally, where the biotechnological tools did not develop, the heat stress responses of livestock are quantified primarily through the phenotypic markers. These include RR, RT, Hb, PCV, cortisol, T3 and T4 (Figure 4). Thermo-tolerance in livestock is recognized as a quantitative trait that is effectively controlled by the genomic regions at the target genes. Identification of specific genes and gene markers that are related to the thermo-tolerance may assist in the selection of superior adapted breeds, which can withstand the heat stress adversities effectively.

Figure 4 Different biological markers for quantifying heat stress response in livestock. These biomarkers include both phenotypic and genotypic traits. These markers may be incorporated in breeding programmes through marker-assisted selection to develop thermo-tolerant breeds. Hb=haemoglobin; PCV=packed cell volume; T3=triiodothyronine; T4=thyroxine; HSP=heat shock protein; HSF=heat shock factor; p53=transformation-related protein 53; p21=cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1; Nramp=natural resistance-associated macrophage protein; SOD=super oxide dismutase; NOS=nitrous oxide synthase; NADH=nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (reduced form); PRLR=prolactin receptor; TLR=toll-like receptor; THR=thyroid hormone receptor.

Many thermo-tolerant genes have been identified and one of the most important among them is the slick hair gene in cattle. The slick hair genes is a single dominant gene, which controls the development of a very short and sleek hair coat in livestock (Huson et al., Reference Huson, Kim, Godfrey, Olson, McClure, Chase, Rizzi, O’Brien, Van Tassell, Garcia and Sonstegard2014). Holstein cattle with the slick hair gene were able to maintain lower RR, sweating rate, vaginal temperature and RT than normal haired animals (Dikmen et al., Reference Dikmen, Khan, Huson, Sonstegard, Moss, Dahl and Hansen2014). Moreover, a recent study established higher milk production from slick haired Bos taurus cattle compared with the non-slick haired cows in hot environments (Hernandez-Cordero et al., Reference Hernandez-Cordero, Sanchez-Castro, Zamorano-Algandar, Rincon, Medrano, Speidel, Enns and Thomas2017). Elevated hepatic mRNA expression of both SOD and CAT genes was also reported during hyperthermic condition (Rimoldi et al., Reference Rimoldi, Lasagna, Sarti, Marelli, Cozzi, Bernardini and Terova2015). Such increased expression in transcription levels of both of these genes probably implies an activated antioxidant defence system, as the primary role of both SOD and CAT enzymes in animals are to provide protection from reactive oxygen species generated during heat stress (Rimoldi et al., Reference Rimoldi, Lasagna, Sarti, Marelli, Cozzi, Bernardini and Terova2015). Therefore, the increased expressions of SOD and CAT genes are identified as a protective response to oxidative stress in animals (Akbarian et al., Reference Akbarian, Michiels, Golian, Buyse, Wang and De Smet2014). Further, NOS is identified as a potent gene involving in the thermal stress responses due to its crucial role in immune, circulatory system and signalling pathways in the animal body (Yadav et al., Reference Yadav, Dangi, Chouhan, Gupta, Dangi, Singh, Maurya, Kumar and Sarkar2016). The NO initiates various cutaneous and vasodilator adaptive responses to local hyperthermic conditions. Moreover, higher production of NOS is essential for increased vasodilation of the skin during heat stress exposure (Yadav et al., Reference Yadav, Dangi, Chouhan, Gupta, Dangi, Singh, Maurya, Kumar and Sarkar2016). Higher mRNA expression of NOS isoforms including inducible NOS, endothelial NOS and constitutitive NOS were reported in Barbari goats and Tharparkar cattle during hyperthermia (Collier et al., Reference Collier, Gebremedhin, Macko and Roy2012).

Elevated temperature induced higher metabolic heat stress in livestock initiates various counter regulatory mechanisms to reduce endogenous heat production. The THR gene regulates the genomic actions of thyroid hormones in animals (Weitzel et al., Reference Weitzel, Viergutz, Albrecht, Bruckmaier, Schmicke, Tuchscherer, Koch and Kuhla2017). The internal metabolic heat production of stressed animals is reduced via hypothyroid activity (Weitzel et al., Reference Weitzel, Viergutz, Albrecht, Bruckmaier, Schmicke, Tuchscherer, Koch and Kuhla2017). Studies suggest the potential of the bovine blood ATP1A1 gene in ameliorating the effects of heat stress, and the P14 locus within the bovine ATP1A1 gene has been recognized as a DNA marker for bovine heat tolerance in marker-assisted selection (Kashyap et al., Reference Kashyap, Kumar, Deshmukh, Bhat, Kumar, Chauhan, Bhushan, Singh and Sharma2015). The genotypic outcomes of blood ATP1A1 gene shows an association with various heat tolerance variables including RR and RT in both Tharparkar and Vrindavani cattle breeds (Kashyap et al., Reference Kashyap, Kumar, Deshmukh, Bhat, Kumar, Chauhan, Bhushan, Singh and Sharma2015). Moreover, higher expression of blood ATP1A1 gene was also reported in cattle breeds during summer, which also indicates its potential role for counteracting heat stress in cattle (Kashyap et al., Reference Kashyap, Kumar, Deshmukh, Bhat, Kumar, Chauhan, Bhushan, Singh and Sharma2015). Further, modified hepatic expression patterns of NADH dehydrogenase gene were also reported in cattle during heat stress exposure (Koch et al., Reference Koch, Lamp, Eslamizad, Weitzel and Kuhla2016).

It has been established that during heat stress conditions, rapid induction of mRNA expression of HSPs occurs in livestock (Shilja et al., Reference Shilja, Sejian, Bagath, Mech, David, Kurien, Varma and Bhatta2016; Singh et al., Reference Singh, Singh, Ganguly, Nachiappan, Ganguly, Venkataramanan, Chopra and Narula2017). The HSPs are a family of proteins that are synthesized as a response to environmental stressors. The enhanced productions of the HSPs are regulated by heat shock transcription factors (HSFs), which are controlled by inducible expression of HSF genes (Figure 4). Experiments conducted using various cattle breeds (Tharparkar and Sahiwal) and Murrah buffaloes showed higher HSF1 mRNA abundance in all three groups during summer (Kumar et al., Reference Kumar, Ashraf, Goud, Grewal, Singh, Yadav and Upadhyay2015). During heat stress, the isoform HSF 1 is activated and binds with heat shock elements in the promoter regions of the gene leading to the enhanced synthesis of HSPs (Gill et al., Reference Gill, Arora, Kumar, Mukhopadhyay, Kaur and Kashyap2017). When cells are stressed, HSPs interact with denatured proteins and prevent the accumulation of protein aggregates, thus helps in maintaining cellular integrity.

Genes that affect the normal cell cycle are also modified in animals suffering from heat stress condition. The mRNA expressions of p21 and p53 genes involving in the regulation of the cell cycle arrest were reported to be up-regulated during extreme heat stress condition (Sonna et al., Reference Sonna, Fujita, Gaffin and Lilly2002). The higher expression of immune response genes such as toll-like receptor (TLR) TLR2/4 and IL (Interleukins) IL2/6 were also reported in heat stressed Tharparkar cattle, which also suggests active immune functions in these breeds to counter heat stress effects (Bharati et al., Reference Bharati, Dangi, Mishra, Chouhan, Verma, Shankar, Bharti, Paul, Mahato, Rajesh and Singh2017). Similar results of increased TLR1, TLR4 and TLR5 expression were reported in indigenous Osmanabadi goats exposed to environmental stressors, for example, heat stress, nutritional stress and combined heat and nutritional stress (Sophia et al., Reference Sophia, Sejian, Bagath and Bhatta2016). The enhanced TLR expression clearly indicates the active immune system of this breed even during heat stress conditions establishing firmly their adaptive capability. Figure 4 describes the traditional phenotypic and genotypic biomarkers to assess the heat stress responses of livestock species.

Multiple stressors are a common phenomenon in many environments, and are likely to increase due to climate change. The findings from these limited reports have made significant contributions, in terms of the understanding of the intricacies of multiple stressors, on physiological, blood biochemical, endocrine and cellular responses in both sheep and goats (Sejian et al., Reference Sejian, Maurya, Kumar and Naqvi2013; Shilja et al., Reference Shilja, Sejian, Bagath, Mech, David, Kurien, Varma and Bhatta2016). These studies also indicated that RR, RT, cortisol, plasma HSP70 and HSP70 gene action may be useful biological markers for quantifying the impact of multiple stressors in both sheep and goats. Through these experiments, the importance of providing optimum nutrition to counter the additional environmental stresses (e.g. heat and walking stresses) in both sheep and goats during adverse environmental conditions has been elucidated. This warrants the development of appropriate nutritional strategies to optimize the economic return from livestock operations in the face of climate change.

Salient amelioration strategies to counter heat stress in livestock

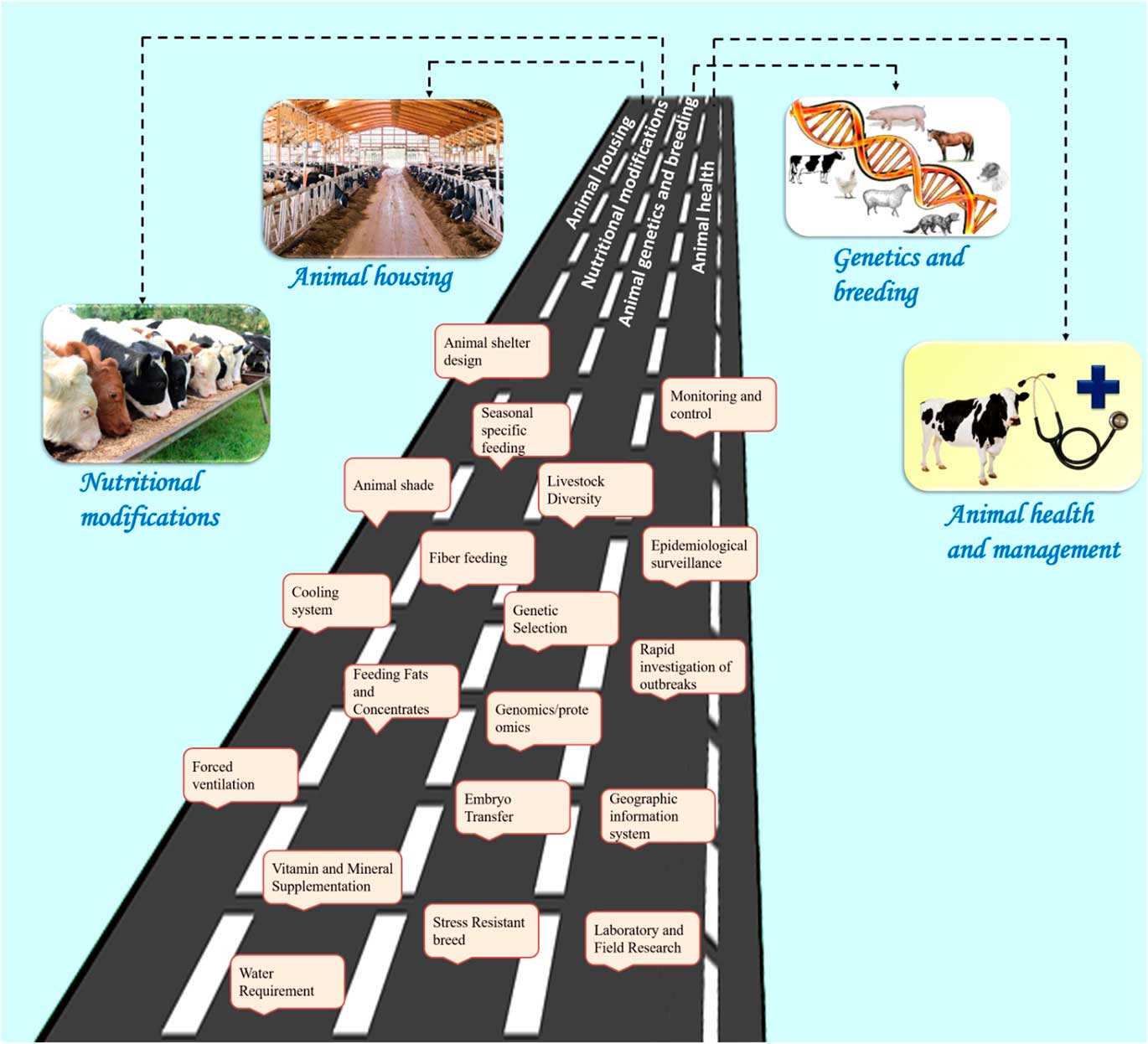

Reducing environmental stress on livestock requires a multi-disciplinary approach with emphasis on animal nutrition, housing and animal health. Figure 5 describes the various amelioration strategies available to counter the heat stress challenges in livestock. Some of the biotechnological options may also be used to reduce thermal stress. It is important to understand the livestock responses to environmental stress in order to design modifications for nutritional and environmental management, thereby improving animal comfort and performance. A range of technologies are needed to match the different economic and social needs of smallholder farmers. The amelioration strategies can be broadly grouped into four categories: housing management, nutritional modifications, genetics and breeding, and health management (Figure 5).

Figure 5 Salient amelioration strategies to counter heat stress in livestock species. These strategies are broadly grouped into four categories: animal housing management, nutritional interventions, genetics and breeding, and animal health management. The housing management strategies include animal shelter design, animal shade, cooling systems and forced ventilation. The nutritional modifications include seasonal specific feeding, fibre feeding, feeding fats and concentrates, vitamin and mineral supplementation, providing cool drinking water. The genetic and breeding approaches include studying the animal genetic diversity, genetic selection for thermo-tolerance through genomic and proteomic approaches, embryo transfer and developing stress-resistant breeds. Finally, the health management strategies include monitoring and control of disease outbreak, epidemiological surveillance measures, rapid investigation of outbreaks, using geographical information system for mapping the disease outbreak and laboratory/field research to find solution to the climate-associated disease outbreak. All these strategies may help to sustain livestock production in the changing climate scenario.

Conclusion

Under the climate change scenario, elevated temperature and relative humidity will impose heat stress on all the species of livestock, and will adversely affect their productive and reproductive potential especially in dairy cattle. The immediate need for livestock researchers aiming to counter heat stress impacts on livestock is an understanding of the biology of the heat stress responses. This will provide researchers with a basis for predicting when an animal is under stress or distress and in need of attention.

Future Projections

Sustaining livestock production in the changing climate scenario requires a paradigm shift in the use of existing technologies. Refinement of the existing climate resilient technologies must be tailor made to suit the needs of the local farmers. Technologies that are developed in one location may not be appropriate for other regions. Therefore, efforts are needed to validate the existing technologies with refinements or modifications to suit the needs of specific locations keeping in mind the requirement of ultimate target group of farmers. Early warning systems should be given top priority to prepare the farmers well in advance for the adversities associated with climate change. Easy to apply water conservation technologies with the incorporation of indigenous knowledge must be developed with inputs from the farmers so that change can be implemented at the local level. Research efforts are further needed in refining the existing heat load indices, which can quantify accurately the heat stress response in the different species of livestock. Moreover, emphasis must be given to conduct research targeting the impact of multiple environmental stresses simultaneously rather than concentrating only on heat stress.

Significant research efforts are also needed to identify fodder conservation measures through the development of national databases on existing fodder resources and bringing in the technologies to sustain those resources to ensure fodder availability throughout the year. Efforts are also equally needed in identifying technologies to mitigate livestock-related enteric and manure GHG emission. Specifically, research efforts are needed to commercialize the laboratory level success in methane mitigation through vaccination approaches. Further, efforts are also needed to develop appropriate disease surveillance measures to counter climate-related vector borne diseases in particular.

The future research needs for ameliorating heat stress in livestock are to identify strategies for developing and monitoring appropriate measures of heat stress; assess genetic components, including genomics and proteomics of heat stress in livestock; and develop alternative management practices to reduce heat stress and improve animal well-being and performance. Special emphasis must be given to study the influence of climate change on the epigenetic changes to understand the differences in adaptive changes that are evolved over generation, which may help to understand the hidden intricacies of molecular and cellular mechanisms of livestock adaptation. Further studies are also needed in identifying ruminant species-specific biological markers for different environmental stresses that arise as a result of climate change and such markers should be included in the existing breeding programmes to develop climate resilient animals through marker-assisted selection breeding programme. In addition, such breeding approaches must be a blend of adaptive, productive and low methane emission traits to evolve a breed which can simultaneously withstand climatic stresses, sustain production and emit low methane. These are the efforts that are needed in near future to sustain livestock production to ensure global food security in the changing climate scenario.

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to the organizers of International Symposium on Herbivores Nutrition (ISHN) 2018 for inviting to write this review. The authors also are thankful to Ms Pragna Prathap for helping us in the preparation of the figures for this manuscript.

Declaration of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest for this manuscript.

Ethics statement

None.

Software and data repository resources

None of the data were deposited in an official repository.