Introduction

It is August 2023, when ‘t Scheldt—an extreme-right website that claims to present Flemish satire—posts a couple of videos of a drunk Theo Francken, a Flemish nationalist politician. The videos picture an obviously very drunk Francken almost falling from his chair while drinking beer, and peeing in the flower beds on the pavement somewhere in the center of Brussels, Belgium's and Europe's political capital. This post on the ‘t Scheldt website is the start of a ‘small scandal’ that threatens the carefully built-up face of Theo Francken. Francken is one of the top politicians of his party, the New Flemish Alliance, a radical-right, Flemish nationalist party in Belgium (Maly Reference Maly2012). He is also vice chairman of the parliamentary delegation at NATO, mayor of a small Flemish town called Lubbeek and very vocal about ‘the decline’ of Brussels. The leakage of a video showing Francken in a backstage situation created a situation of context collapse (Marwick & boyd Reference Marwick and boyd2011). His drunken self became visible in the whole Flemish hybrid media system (Chadwick Reference Chadwick2017): a situation that caused him to ‘lose face’ and forced him to engage in ‘face work’ to avoid further damage.

Analyzing digital face-work

Following Goffman, I introduce the notions of digital face-work and the digital interaction order to highlight how politicians manage such ‘small scandals’ in relation to the affordances, and sociocultural and economic logic, of digital media platforms. The commercialization of mass media introduced a dialectic where politicians increasingly have to present themselves as full-blown persons to an electorate. Lempert & Silverstein (Reference Lempert and Silverstein2012; Silverstein Reference Silverstein2003) famously termed this type of political face-work ‘Message’. In contemporary politics, message is not just the literal message, it also encompasses the publicly imaginable character becoming visible through a collage-in-motion of communicative events. Digital media only reinforce and complexify those tendencies. Creating and ‘maintaining face’ throughout a hybrid media system is now at the heart of what politics is about.

There is a long and rich research tradition in which Goffman's concept of face-work is used to analyze political discourse (Chilton Reference Chilton2004; Bull Reference Bull2008; Bull & Fetzer Reference Bull and Fetzer2010; Hanke Reference Hanke2021). But even when those studies zoom in on face-work in a digital environment, the micropolitics of politicians constructing and maintaining face in relation to the sociotechnical characteristics of digital media is, as far as I know, barely analyzed. This is problematic, as digital platforms are not just spaces that afford interaction, they are also (algorithmic) actors that co-construct the face-work of their users (Maly Reference Maly2024a). Platforms have agency in co-determining who is part of the interaction and thus who can assign meaning to the interaction and one's face.

Digital face-work is a sociotechnical assemblage and should be analyzed as such. Digital media are part of what Goffman (Reference Goffman and Goffman1967:35) called the social situation of interaction. The social situation not only encompasses the direct occasion—a meeting or a chat with friends—and its associated sociocultural conventions, but also the physical setting in which the speakers perform. According to Goffman, all should be studied to understand the meaning of interaction as they all potentially give direction to it. Goffman stressed the complexity of that social situation and warned against bypassing it (Goffman Reference Goffman1964) by focusing only on specific parts of the speech or the social situation. In the end, those seemingly unimportant details can be of major importance in the construction of meaning (Blommaert, Spotti, & Van der Aa Reference Blommaert, Spotti, Van der Aa and Canagharaja2017:351). It is in the coming together of actors in a specific social situation that certain formats and (moral) scripts enter the picture. Platforms are an active part of the social situation of digital interaction (Maly Reference Maly2024a). They breed specific platform cultures that give birth to specific interactive practices (Maly Reference Maly2023b; Maly & Beekmans Reference Maly, Beekmans, Arnaut, Parkin, Spotti and Maly2025). To understand and analyze digital face-work we thus need to understand:

(i) how platforms become part of the social situation,

(ii) how digital platforms afford and direct interaction (Georgakopoulou, Iverson, & Carsten Reference Georgakopoulou, Iverson and Carsten2020),

(iii) how users interact in relation to the specific characteristics of online mediated interaction (such as SpaceTime compression (Thompson Reference Thompson2020), modes of communication, many-to-many communication, and the algorithmic logic of digital media),

(iv) and how the techno-economic context of those platforms influences platform cultures and digital interaction.

Digital face and the digital interaction order

Digital media democratized a specific form of mediatized publicness that gave rise to a culture of intimate self-presentation for large audiences (Duffy Reference Duffy2015). What we call influencer culture is emblematic for this digital publicness. This pinnacle of digital culture, characterized by ‘staged intimacy’, ‘staged authenticity’, and parasocial communication, is now also omnipresent in the field of politics. Politicians use digital platforms to create message and increasingly embrace influencer tactics in creating digital face in relation to the affordances of digital media. Goffman famously argued that face is ‘a positive social value a person effectively claims for himself by the line others assume he has taken during a particular contact’ (Goffman Reference Goffman and Goffman1967:5).

Political face-work is usually associated with the need to produce a ‘positive face’ as the politician's political survival ‘ultimately depends on the approval of a majority of people in their own constituency’ (Bull & Fetzer Reference Bull and Fetzer2010:158). The latter perspective on political face-work assumes a ‘winner takes all’ context like in the US and the UK. It also assumes political communication to be non-ideological, directed to a market of voters choosing the best product ‘objectively’. And last but not least, it assumes a shared public sphere in which politicians need to generate this positive social value vis-à-vis the whole electorate. In a digital environment, face-work is somewhat different and this is for several reasons:

(i) The construction of a digital face is done in a layered, stratified, translocal, and polycentric context (Blommaert Reference Blommaert2010) stretched in time and space. It is constructed in relation to a potential infinite series of audiences that speakers do not necessarily see or engage with in the moment of interaction. Nor do politicians speak to or even want to convince ‘all those niches’.

(ii) This has the effect that politicians stylize their online interactions in relation to ‘a public’ as theorized by Warner where ‘the agonistic interlocutor is coupled with passive interlocutors, known enemies with indifferent strangers, parties present to a dialogue situation with parties whose textual location might be in other genres or scenes of circulation entirely’ (Warner Reference Warner2002:420). And interestingly, all of those audiences can contribute to generating attention/virality which is a central goal in a political field dominated by the attention economy.

(iii) Platforms direct interaction through affordances and interfaces. As a result, they breed specific platform cultures that in turn give birth to specific interactive practices (Maly Reference Maly2023b; Maly & Beekmans Reference Maly, Beekmans, Arnaut, Parkin, Spotti and Maly2025), but also specific, affectively attuned audiences (Papacharissi Reference Papacharissi2016).

In the contemporary media environment, a politician's face is thus constructed in relation to the affordances of a plethora of platforms and to a multitude of others. Digital face-work is not only shaped by the communicative resources somebody has, it also demands carefully managing one's front stage in relation to an imagined audience (imagined by looking at uptake metrics and comments), the sociotechnical space, and the normativities associated with the social occasion. Platforms co-construct (Maly Reference Maly2022a) the digital interaction order through their affordances, interfaces, community guidelines, moderation practices, and overall algorithmic organization. It is, for instance, the algorithmic organization of a platform that determines what becomes visible (Bucher Reference Bucher2018) and thus who will become part of the interaction and who will never hear about it. Platforms program sociality (van Dijck 2013): they format and direct how and with whom we interact in the hope of keeping users hooked to their screens. Digital interactional rules, expectations, and normativities are at least partially informed by technical characteristics of platforms (affordances, algorithms, interfaces) and cultural interactions with those technicities in the form of media ideologies, algorithmic imaginaries (Bucher Reference Bucher2015), and platform cultures (Maly Reference Maly2023a).

The fact that platforms are active participants in digital interaction (Maly Reference Maly2022a) is an important variable in the designing of interaction. Georgakopoulou, Iversen, & Carsten (Reference Georgakopoulou, Iverson and Carsten2020:98) introduce the concept of directives, defined ‘as prompts to users for engaging in specific posting practices and relational actions’, to analyze this steering impact of platforms. Directives request, demand, encourage, discourage, refuse, or allow certain communicative behavior. Platforms encourage us not only to use our real names, or post live updates, they also encourage us to post regularly and interact with our audience if we want uptake. These directives get their force from the fact that they are embedded in what van Dijck & Poell (2013) call social media logic, namely, the programmability, popularity principle, connectivity, and datafication strategies of platforms. Politicians like Theo Francken post on an almost daily basis in the hope of connecting with and expanding their fan base through careful face-work. The rhythm of digital face-work is at least partly shaped by social media platforms that incentivize politicians to compete in this endless battle for attention. Ergo, these sociotechnological practices are part of the digital infrastructure that is geared to keeping us as online as possible. This is a matter of design (Eyal Reference Eyal2014) and of human digital discursive activity. It is thus not a coincidence that in the digital arena, influencers, activists, politicians, journalists, and intellectuals all fight to capture our eyeballs; it is a result of the structural dimensions of digital interaction.

The digital environment shapes a specific interaction order (Goffman Reference Goffman1983). In the digital interaction order, the power that platforms have in setting the rules and directing the discursive practices that coordinate daily social relations and sense-making of people is not fully comparable with offline communication. How people interact on social media platforms is the result of a complex interplay between individual ‘agency’ and the directive force of the digital platforms. Users not only interact using those technical affordances, they are at the same time integrating themselves into the digital cultures that are emerging and developing in relation to the platform affordances and algorithmic structures. The difference between on- and offline interaction is also one of scale and depth. In an online context, a politician's digital face is rarely without fiercely negative comments that attribute meaning to the performance of that face. Digital face-work is always face-work vis-à-vis a public, and thus a multitude of people—with different backgrounds, different opinions, and different ideological dispositions—who now can talk back, and thus have the possibility to attribute meaning to the politician's performance of face that also influences others. In digital face-work, one needs to succeed in enregistering one's face over the long haul and in interaction with a potentially infinite number of audiences in different TimeSpaces. As a result of their integration in the algorithmically steered attention economy, politicians now increasingly mobilize strategic intimacy, authenticity, and parasocial communication (Maly Reference Maly2021) to build a community based on one's digital face.

Small stories

This care for one's digital face is reflected in the initial discourse a politician produces. The input discourse will ‘characterize the world in which it attempts to circulate’ (Warner Reference Warner2002:422) not only through a specific type of content, addressing specific types of audiences, but also by its integration in a specific type of sociotechnical economy: it needs to be in tune with the different platform cultures if it wants to circulate. Over the years, Theo Francken has done this skillfully. He has established himself as a hardline Flemish nationalist specialized in migration and as tough on crime. He is also very vocal about Brussels, and especially about how the city has been managed in the last decades. His discourse is characterized by an edgy parler vraie that clearly does not try to convince more left-leaning voters. He is outspokenly right-wing, though on migration, integration, and criminality—all things that do not generate a positive value from a more left-wing audience but are loudly applauded online by his right-wing fan base. And above all, his radical statements usually generate uptake in the form of likes, shares, (nasty) comments, and invitations by mass media to explain his social media postings. Successful digital face-work, at the very minimum, means uptake from the affective public (Papacharissi Reference Papacharissi2016) that one has built around one's account and ideally expansion of this public by producing entertaining, controversial, or affective content that gets you invited into the legacy media.

Francken, like most contemporary politicians, not only posts about deeply political items on social media, he also regularly posts so-called small stories that narrate ‘trivial events from the teller's everyday life, rather than big complications or disruptions’ (Georgakopoulou Reference Georgakopoulou2021:2). Francken regularly posts small stories that depict him BBQing, cleaning streets in his hometown, and so on. Especially on his Instagram, we see pictures with his family and his dog or see him drinking lattes, cooking Brussels sprouts, or working out. We can even share very intimate events like his kids’ birthday parties, or read the comments that the teacher wrote about his children at the end of the school year. His followers get to ‘know’ him as a person and not just as the politician. Even though small stories are used to communicate ‘trivial events’, those stories are meaningful and important for contemporary politicians as they are instruments of identity communication and thus contribute to a politician's face. They contribute to a ‘politics of trust’ (Thompson Reference Thompson2008). Francken uses social media to create a political face that is multidimensional. He presents himself not only as a passionate Flemish nationalist or the former State Secretary of Asylum and Migration; he is also a ‘normal Flemish guy’. He embraces staged intimacy not only to create an authentic face, but also to connect with his followers or to launch calls for action to his followers. It is through this combination of posts that Francken builds an audience, but also succeeds in creating a specific political persona.

Such ‘small stories’, Georgakoupoulou argues in later work, are programmed and amplified by social media. She identifies three phases in the development of small stories within digital platforms. In the first phase, platforms encouraged people to share the moment now, in the second phase it seduced people to show the moment in terms of sharing ‘selfies’. In the last phase, the sharing of stories programmed as ‘distinct features, integrated into their architecture and named as such’ (Georgakopoulou Reference Georgakopoulou2021:2). The small-stories format is, in a post-digital era, steered by platforms. On a daily basis, platforms ask us to share ‘what's on our mind’ (Facebook) and encourage us to share ‘stories’ (TikTok, Instagram, Snapchat, and now also YouTube and Facebook) from our daily lives. This digital format of interaction is visible in the narrative strategies dominant not only in influencer culture, but now also increasingly in political culture. Among other things, influencer culture has normalized the sharing of intimate information to a large audience. Staged intimacy and authenticity (Gaden & Delia Reference Gaden and Delia2014) have now come to be expected from YouTubers (Raun Reference Raun2018; Dekavalla Reference Dekavalla2022): they have become part of the digital interaction order. Note here, that this intimacy is staged, and thus performed, and that influencers do not really give their followers insight into the backstage—they suggest or perform that intimacy and backstage access.

Small scandals

This embrace of digital culture and digital media coincides with a rise in what I label, following Georgakopoulou's small stories, small scandals that politicians need to manage. Scandals are of course not new to politics; they are social phenomena that are closely related to the existence of mass media. Thompson argues that scandals are mediated events that started to emerge in the late eighteenth and nineteenth century. Their rise should be understood in relation to ‘broader social transformations, including the changing economic bases of the media industries and the rise of journalism as a profession … and changes in the social context of politics’ (Thompson Reference Thompson2008:8). The latter is especially the case in the post WWII context where ideological mass parties gradually weakened, and message politics (Lempert & Silverstein Reference Lempert and Silverstein2012) took their place. Central to this ‘new type’ of politics is the politicians’ face: politicians sell their character to an audience and try to build a relation of trust vis-à-vis that part of the audience that they want to convince. As I already argued, politicians love to present themselves with their family in seemingly non-political settings in order to construct an image of themselves that they hope will appeal to their militants.

The presentation of the self through digital media introduces a ‘new fragility’ (Thompson Reference Thompson2020). Thompson sees this new fragility in the increasing complexity in controlling the boundaries between back and front stage. Digital technologies like the cell phone, but also all kinds of apps like Zoom or WhatsApp, increase the chance of slippage. Such slippage from back to front stage results in all kinds of ‘small scandals’. Think of all the politicians and experts who were caught zooming on the news in their underpants. This slippage between back and front stage is not merely a technical issue. It is the result of how people—even trained politicians—define the social situation and the accompanying social rules. Management of face in a digital environment is clearly limited to the stuff that appears on screen. Note also, that in digital culture, the backstage not only needs to be managed when people interact online in their professional capacity: every move—even offline—can be filmed an inserted into the front stage of political interaction as the Francken case shows.

Small scandals are the result of seemingly ‘small stuff’ from a politician's backstage that is accidently brought into the front stage by the politician or on purpose by others. Contrary to historical political scandals like the Watergate scandal, these ‘small scandals’ usually do not deal with purely political practices but have impact because they alter the face of the politician. Small scandals are all about slippage of information that affects the positive values assigned to a political face by the supporters of the politician. As such, they are political because they target one of the main ingredients of contemporary politics: the careful constructed character of the politician. Small scandals do not necessarily bring careers to an end, but they do undermine the face and the trust people have in the politician. One small scandal can alter the respect and support some militants give. But a series of small scandals can mean the end of a politician. Small scandals thus force politicians to do face-work in the hope of minimizing the damage and restoring face.

The rise in small scandals is a consequence of the interplay of the democratization of publishing and the banalization of recording, as Thompson (Reference Thompson2020) argues. This interplay creates an omnipresent danger that others might film and publish one's backstage. In other words, digital face-work is not limited to the online—it is a 24/7 affair. Connected to this management of front and backstage is what Marwick and boyd coined as context collapse (Marwick & boyd Reference Marwick and boyd2011). They describe context collapse as the flattening of multiple audiences on social media into one. The notion assumes that people online need to construct and maintain face in relation to different groups of people, people who have varying access to back and front stage offline. The danger of context collapse, Marwick & boyd argue, makes it difficult to differentiate self-presentation strategies, and thus manage the boundaries between back and front stage. The underlying assumption of the notion of context collapse is that context is connected to specific individuals and groups of people, and that these groups of people collapse online into ‘one context’. Many sociolinguists (Szabla & Blommaert Reference Szabla and Blommaert2018; Moore Reference Moore2019; Tagg & Seargeant Reference Tagg and Seargeant2021) rightly argue that context has never been something stable, nor is it something outside of communication, but it is co-created through interaction (Gumperz Reference Gumperz1982; Blommaert Reference Blommaert2005), and this is not different—at least in essence—online. In his PhD, Goffman described how people on a small island in the 1950s also lived in a context of ‘extensive mutual monitoring’, needed to maintain face not only in the direct presence of people but also when people were not necessarily in ‘response presence’ (Moore Reference Moore2019:282).

What is different in the digital era is that, as a result of the technological affordances and digital characteristics of digital interaction (persistence, scalability, searchability, and replicability; boyd Reference boyd2014; Varis Reference Varis, Georgakopoulou and Spilioti2015), messages can travel and be seen and evaluated by different audiences on much larger scales. Also, there is now ‘proof’ of backstage behavior in the form of film or photos that add new layers of complexity to the art of political face-work. People indeed succeed quite well in designing/managing context online, which requires them to take several variables into account, including the ‘nature of online writing’, and ‘the role of a particular site within that mediascape’, and the ‘perceptions of its affordances’ (Tagg & Seargeant Reference Tagg and Seargeant2021:10). If, like in the case of Francken, compromising video material all of a sudden dominates the web, management of context and one's face is multifaceted but also multilayered. Politicians produce face not just on social media, but in the whole hybrid media system (Chadwick Reference Chadwick2017), and they will try to limit the scope and impact of face threatening activities by managing context design.

Theo Francken: Saving political face in a hybrid media system

In the contemporary hybrid media system, political campaigns never stop. Face management is essential in those campaigns, and thus for the careers of politicians. The time that election campaigns started a couple of months before the election is long gone. Moreover, the idea that only political parties and candidates are campaigning is an illusion. The internet and the democratization of recording have enabled new forms of ‘black PR campaigns’ to be set up to destroy the face of political adversaries. The videos of a peeing Theo Francken are an example of such a negative messaging campaign. They are also a clear-cut example of context collapse that demanded urgent context design (Tagg & Seargeant Reference Tagg and Seargeant2021) from Francken and his party.

The ‘t Scheldt website that launched this campaign was set up by two right-wing Flemish nationalist entrepreneurs in 2018 (Antonissen & Stevens Reference Antonissen and Stevens2023). The site is covered in secrecy. All authors write under pseudonyms, and the two founding members have tried to keep their involvement secret at all costs. The goal of the site was to damage the political adversaries of the extreme-right political party Flemish Interest and the radical-right N-VA (the New Flemish Alliance), to settle old (political) scores, and to normalize radical right Flemish nationalism. Up until 2021, the website targeted all enemies of those two Flemish nationalist parties. On several occasions, the site targeted Conner Rousseau, the young president of Vooruit, a social democrat party. They published a video of him partying during COVID, seemingly breaking government policy. This was the first small scandal that was ever publicly assigned to him. Later ‘t Scheldt accused him of toxic sexual behavior and eventually forced him to out himself as bisexual (Maly Reference Maly2023c). The president of the liberal party, OpenVLD, was also targeted by the site, just like politicians from the Green party and many others. ‘t Scheldt was clearly a black PR website targeting the non-Flemish nationalist parties.

But ‘t Scheldt is more than just a vehicle for political settlements and negative messaging campaigns. All content, one way or another, contributes not only to the normalization of Flemish nationalism, but also to a right-wing stance on the rule of law, police in the streets, criminalization of migration—‘t Scheldt is a metapolitical actor (Maly Reference Maly2020). The roots of metapolitics go back to La Nouvelle Droite, the far-right school of thought that started in France in the sixties of the twentieth century. The number one of La Nouvelle Droite, Alain de Benoist, argued that the right should understand that cultural power ‘acts upon the implicit values around which the consensus indispensable to the duration of political power crystallizes’ (de Benoist Reference de Benoist2017:7). Referring to the work of Antonio Gramsci, he argued that the left had acquired hegemony and that the far-right had to start a cultural battle by intellectual means. In the contemporary age, we see that metapolitics has taken a completely different form. Metapolitics is not the monopoly of intellectuals anymore; as a result of digital media, metapolitics has been ‘democratized’ (Maly Reference Maly2024b) and, as a result, trolling, memes, just like black PR campaigns are now part and parcel of the metapolitical game trying to change culture.

In the case of ‘t Scheldt, we see that the site uses the affectively tuned algorithmic logic that dominates the hybrid media system to make ‘visible’ what is ‘hidden’ and, as such, it contributes to establishing a powerful myth about ‘mainstream politicians’ being untrustworthy (Maly Reference Maly2023a). ‘t Scheldt engages in this cultural battle from a marginal position in the hybrid media system. But, in using digital media platforms, it not only forms an affective audience around the website and their social media, it sometimes also succeeds in setting the agenda in the whole Flemish media. The case of Theo Francken is one such example.

The Francken case is remarkable, because the target is an outspoken, right-wing Flemish nationalist. After Bart De Wever, who has been the president of N-VA for the last twenty years and is maybe the most influential politician in Flanders, Theo Francken is one of the party's most prominent politicians. He is also one of the hardliners in N-VA, ideologically not that far removed from the extreme right-wing party, Flemish Interest (Maly Reference Maly2012). The fact that such a prominent N-VA politician is now the target of a black PR campaign from ‘t Scheldt should be understood in relation to (i) the 2024 elections where Flemish Interest was polling as likely to become the biggest party, finally outnumbering N-VA and (ii) the fact that one of the founders from ‘t Scheldt, who was very sympathetic with N-VA, has left the site because his former companion also wanted to target N-VA politicians (Stevens & Antonissen Reference Stevens and Antonissen2023). Since 2021, ‘t Scheldt is now de facto a medium working to normalize the extreme-right party Flemish Interest, and the videos of a peeing Theo Francken were ideal to destroy the face of one the important electoral competitors of Flemish Interest.

(Destroying) Francken's face

On August 25, 2023, the extreme-right satirical website ‘t Scheldt posted an article titled ‘Just to understand. Is this Theo Francken?’ (De Bekbroeder Reference De Bekbroeder2023) on their site and pushed it on social media. The article did not contain text, but included a couple of smart-phone videos that seemingly ‘speak for themselves’. They were clearly set up to start a small scandal as they targeted an important ingredient of Francken's face. To explain this, we need to dig a bit deeper into his digital face. Over the years, Francken's face has generated a dedicated following that interacted loyally with the politician, but also maybe an even larger group of more liberal and left-leaning people that detest and even hate him as passionately. Francken's digital face, even on a local Flemish scale, is constructed in relation to a public consisting of different niches that contextualize his messages differently, and thus also attribute a different face to him. Both groups, and this is clearly different from classic offline face-work, also contribute to his virality and thus visibility. They are both a crucial part of his face. And maybe more important, their specific evaluations of his face are a crucial part of his visibility in the attention economy. His controversial tweets are thus in tune with the digital interaction order: they help to grab the attention of the people, and become visible not only on social media but in the whole hybrid media system. Even more, the negative evaluations of his face contribute to a positive value his fans assign to his messages.

Controversy is thus not necessarily a problem for him. The problem with the videos the ‘t Scheldt website launches is that they target a key part of his digital face that his supporters assign positive value to. We can illustrate this part of his digital face with his launch of the hashtag #opkuisen ‘#CleanUp’ in 2017. He posted this hashtag in relation to an ad hoc refugee camp in the Maximiliaan park in Brussels. In this post, he mentioned the hashtag #cleanup with the information that the police had entered the camp and arrested fourteen people while informing his followers that the park was now almost empty (Francken Reference Francken2017a). Depending on one's contextualization universe, the hashtag could refer to the camp itself but could also be read as referring to the people. The post went viral, because it was controversial. 2.7k people interacted with this post and over 118 people shared it. It resulted in harsh criticism from center and left-wing politicians and citizens. At the same time, Francken also received applause from his fans and far-right niches, including from the Flemish Identitarian movement Schild & Vrienden (Maly Reference Maly2018), who used the hashtag later when they organized clean-up activities, using the ambiguous meaning of the hashtag to their advantage. The tweet went viral, and mass media reported on it, as did politicians from different political parties. The controversial nature of the hashtag for some, and the support from his followers, pushed his voice into salience in the whole hybrid media system.

The hashtag was well chosen. It was radical enough to please, and even expand his fanbase to the right of the political spectrum. At the same time, because of the inherent ambiguity, the hashtag could be explained in different ways. The more radical meaning (to clean up people) could be denied as not an intended meaning. And, that was exactly what he did. When Francken was eventually forced to explain his comment and thus to save face, he posted on Facebook: ‘I don't clean up people. I clean up problems. And I'm going to keep doing that. The left-wing ruins are immense’ (Francken Reference Francken2017b). Ergo, he stressed one of the possible meanings and he got away with it—at least in the sense that he remained one of the most popular Flemish politicians at the time, while at the same time being despised thoroughly by the left. ‘To clean up’ was now part of his digital face. In the years after, he regularly used the concept in the context of politics in general (cleaning up the political mess other parties create), but mostly he used it in relation to issues of asylum, clean streets, and nature. In August 2023, for instance, he posted how he, together with volunteers, cleaned up the municipality of Lubbeek where he was mayor (Francken Reference Francken2023a), echoing the activities of extreme-right identitarian movement Schild & Vrienden. In July 2023, he used the hashtag in an interview from which he posted quotes on Facebook. In that interview, he talked about the need to clean up the areas around all the train and metro stations in Brussels because they were full of junk, noting that the urine smell was unbearable (Francken Reference Francken2023b). Earlier in 2019, he proudly posted a picture of himself campaigning together with people, who he claimed asked him when he will be cleaning up Brussels (Francken Reference Francken2019). Clean streets, especially in Brussels, achieved through a ‘hard cleaning up’ policy, was essential to his digital face.

The virality of small scandals

It is exactly in relation to Francken's carefully constructed face that we should understand the political relevance of the small scandal that took shape in August 2023. The moment ‘t Scheldt posted the videos they immediately went viral on social media: the videos were juicy, controversial, and a top politician was the subject. Indeed, it is not really surprising that the videos immediately went viral and were picked up by mainstream media. They are consistent with the dominant digital interaction order where grabbing attention is a key value.

Two popular, more sensationalist Flemish newspapers, Het Laatste Nieuws (Redactie 2023) and Het Nieuwsblad (Gyssels Reference Gyssels2023), posted an article on this small scandal later in the afternoon of August 26th. Interestingly, both mention the virality of the clips on social media and legitimate their posting an article on the videos in light of this virality: ‘The video is already circulating heavily on social media. Even politicians from other parties are making fun of it. It concerns three videos, showing Theo Francken who has clearly had one drink too many’ (Gyssels Reference Gyssels2023). In other words, it is the virality that makes it a political event and, from this perspective, newspapers decide that the small scandal is now newsworthy. Legacy media now take over ‘news’ that is being produced by an extreme-right website in order to have political impact. And, they present it as just that: news. Even though journalists would normally never publish such videos from the private sphere, as this would be against their deontology, they now can do this because the ‘news is already out’. It is thus the virality on social media—and the legacy media's search for part of that attention—that makes the small scandal visible in the whole hybrid media system. And, more importantly, these legacy media drive traffic to an obscure far-right website like ‘t Scheldt. This traffic manifests itself in several reactions posted underneath the post of ‘t Scheldt, mentioning another case involving a far-right Flemish Interest politician, driving through a red light with his Maserati. That is interesting, as this fact was not mentioned in the ‘article’ ‘t Scheldt posted, but it was in Het Nieuwsblad.

Contrary to ‘t Scheldt, the two, more popular, newspapers—following their deontology—do contact Theo Francken for a first response and to verify that the videos are real. Francken is quoted as affirming that the videos are real: ‘From a night off with too much drinking and stupid behavior a year ago, after a difficult and stressful period. Apparently captured by someone. Embarrassing. I don't want to justify it, but at the end of the day I'm just a human being’ (Gyssels Reference Gyssels2023). Francken's response here is not yet a full apology. It reads more as an ‘explanation’ and a way to normalize and downplay his behavior. It is not surprising, then, that the small scandal does not end here. Online people still make fun of Francken in the best case; and, in the worst case, his behavior is framed in terms of the hypocritical and untrustworthy nature of all politicians.

Note that, in this context, both Het Laatste Nieuws and Het Nieuwsblad frame Francken's behavior in relation to other peeing incidents in the weeks before. We should thus understand the viral qualities of the videos in relation to an event that happened a couple of weeks earlier when the then-Belgian minister of justice, Vincent Van Quickenborne, was compromised because several guests at his birthday party peed against a police van in front of his house—a police van that was there to safeguard the minister after several death threats. That is, politicians peeing had become a genre in the news, and Francken was next in line.

Challenging Francken's political face

By 7pm on August 26, 2023, Francken clearly felt the need to nip the small scandal in the bud and reacted on his social media in order to save face. The timing is relevant (Chadwick Reference Chadwick2017), as it avoided a further blowing up of the story online. By the time qualitative legacy media like VRT, De Standaard, or De Morgen reported on the incident, they did it with the apologies of Francken included in the article. This was the apology he posted on his Facebook (Francken Reference Francken2023c), a dry, text-only message, shown in Figure 1 with the English translation below.

Dear Friends,

I like handing out (verbal) punches, so I also have to be able to take blows as well.

A year ago, after a difficult and stressful period, a night off with too much drinking and stupid behavior. Apparently recorded by someone and now—a year later—released by certain media. Embarrassing. I don't want to justify this. Urinating in public is nothing to be proud off and neither am I. I am not less, but certainly not more than anyone else and could be fined just like anyone else for this kind of behavior. I understand that some people are disappointed when people who are supposed to be role models exhibit such behavior. But at the end of the day, I'm only human with all the faults and flaws that come with that.

Good evening,

Theo

If we compare this apology with the initial remarks quoted in the popular newspapers, we see that Francken now goes at length to offer an apology. The message is clearly designed to restore face, a restoration that is necessary in order for Francken to be able to function normally in politics again. Or, in the words of Goffman, it is a necessary condition for future interaction (Goffman Reference Goffman and Goffman1967:216) in politics. In his career, Francken has used his social media not only to articulate his political thoughts, but also to build a community around him. It is this community that he addresses with the informal salutation ‘Dear friends’ and ‘Good evening, Theo’. It is in relation to these digital ‘friends’ that he uses face-work to counteract the peeing incident which threatens his face. This context of ‘friends’ is further enhanced by the mobilization of staged intimacy (Marwick & boyd 2011) through the explicit contextualization of his behavior as occurring in ‘a heavy and stressful period’ with ‘too much booze and stupid behavior’ and him being just human (something that he feels the urge to mention explicitly), all in the hope of getting some understanding. But, it is clear that the central topic of his post is the apology related to the realization that this behavior is wrong, and that there are no excuses.

Figure 1. Facebook post by Theo Francken with an apology for his behavior.

Such face-work, we know, follows habitual and standardized practices. The videos call attention to his misconduct. In response to this challenge to his face, Francken offers an apology. In this apology he shows regret for his behavior, labels it as ‘embarrassing’, and even as a crime, indicating that he understands the severity of his actions. Ergo, he tries to show that ‘he does not treat the feelings of the others lightly’ (Goffman Reference Goffman and Goffman1967:220). Contrary to offline interaction, digital interaction does not occur in a shared TimeSpace. The mediatization and thus public nature of the apology changes the interaction. First of all, the offender has to prepare the offering in full before posting and cannot change his or her narrative in relation to immediate feedback. The offering thus has to be produced in relation to an imagined audience (Marwick & boyd Reference Marwick and boyd2011; Tagg & Seargeant Reference Tagg and Seargeant2021). That is visible in Francken's statement where he claims ‘I am not less, but certainly not more than anyone else and could be fined just like anyone else for this kind of behavior’. In this statement, we see how he imagines that this audience will see this as what it is: a criminal offence. The imagination of one's digital audience is not always easy, especially not when one has over 200,000 followers. At the same time, digital media afford the careful surveillance of people. If we look underneath the original video post on ‘t Scheldt, we see several reactions following this line of argumentation. Considering that Francken reacts to the post of ‘t Scheldt and is a follower of the site on social media, we can assume that he read the comments and stylized his apology in relation to those comments and others he encountered online. This assumption is also found in the apology's intertextual connection with the following comment:

This is public drunkenness and public indecency; both are punishable. Especially if you hold a public leadership position, namely mayor and parliamentarian. If everyone is equal before the law in this country, then Theo Francken will be punished appropriately in no time. Oh, of course that's not possible, because because Theo is a parliamentarian, he enjoys political immunity. Theo likes to show off in parliament and in the VRT studios. Will he now be just as resentful and say: ‘Forget my immunity, I will pay the appropriate fines, right?’ I do not think so. And this is what we have been seeing for quite some time now with N-VA excellencies, the same suit and trousers, just like with those other politicians who feel superior to the plebs. I wrote it here before, the N-VA has become ‘le nouveau CVP est arrivé’!

This pseudonymous user's criticism seems to be exactly the criticism Francken has imagined his audience would have after seeing those clips. The user focusses on the fact that peeing in public is a felony, that politicians should be prosecuted like normal people, but also that Theo is very vocal in the mass media. Francken's offer mirrors the main topics of this comment.

My dear friends: The uptake of the offering

Whether or not Francken's apology is enough to restore his face will depend on the uptake. Traditionally, after the challenge and the offering, the third move follows: the acceptance of the offering. In this last stage, we again see how digitalization affects face-work. Francken is apologizing with his own audience of 200,000 people in mind. His Facebook friends are not only the imagined addressees of his posts, they are also important mediators. His use of social media to communicate his apologies can only work if the followers not only see the message, but also interact (preferably in a positive manner) with the message. The main assumption of the message is that it should generate enough interaction to become visible on the timelines not only of fans, but also of journalists and politicians. The interaction with the post thus serves a dual purpose: (i) it helps make the post visible and (ii) it also adds meaning to the offering. The more people who publicly support and accept the offering, the less it will be seen as an issue of political importance to journalists, and thus the less it will stick to his face and become a large uncontrollable scandal.

In this light, the format of the post he uses is interesting. As we saw, he starts his post with ‘Dear Friends’. This colloquial language not only echoes interaction with people one knows well, it indexes a classic format he regularly uses. The salutation is part of the context design of the post: he is asking to accept his apology as a ‘friend’—a ‘friend’ his followers have known for a long time. Interesting, though, is that in the context of Facebook, ‘friends’ of course does not refer to actual friends, but to the programmed relation one has with others. The salutation ‘Dear friends’ thus also indexes the ‘parasocial relation’ that he has constructed over the years: it elevates the programmed sociality of the ‘friend’ function of Facebook discursively to the status of ‘real friends’ and facilitates an imagination among his followers that they are part of a real community and that they have real and meaningful interactions with him. The evocation of friendship is functional, not only for establishing a bond with his followers, but also as a call for them to take it easy on him, after all ‘he is just human’. We all know that it is easier to forgive our friends than our enemies.

The power of this parasocial relation with his followers becomes clear as we look at the highlighted comments of his ‘Top Fans’. The Top Fan label is algorithmically awarded on a weekly basis to the fans who are most active on the page. Active can include watching the page's videos, liking or reacting to its content, and commenting on or sharing its posts (Facebook 2020). With the Top Fans label, Facebook introduced gamification to make ‘fans’ more active and thus to help in producing viral ‘organic’ content (Maly Reference Maly2020). The label also helps in constructing a community and strengthening the parasocial bond: the label lets top fans feel that they are a recognized part of this community, and thus some sort of ‘friend’. The impact of this programmed sociality and Francken's framing of it in terms of ‘real friends’ is visible in the reactions of his top fans. The most popular reactions ‘accept the apologies’ and frame his behavior in the same terms as Francken. ‘He is just human. And humans make mistakes’. The deeply Christian cultural value—he who is without sin, throws the first stone—is successfully reproduced and contributes to the power of the apology in restoring Francken's face. One of the most popular Top Fan reactions stated it like this: ‘Respect, at least you come clean and don't normalize it, Mr. Theo, there are worse things in life, and everyone makes mistakes  ’. This particular comment, as a result of the 305 likes it received, was algorithmically presented by Facebook as the most important and was thus given visibility underneath the post. In other words, the Facebook algorithms highlighted it as emblematic of how people felt about Francken's apology.

’. This particular comment, as a result of the 305 likes it received, was algorithmically presented by Facebook as the most important and was thus given visibility underneath the post. In other words, the Facebook algorithms highlighted it as emblematic of how people felt about Francken's apology.

It is in such examples that we see that digital face-work is a sociotechnical assemblage. We see it also in the comments that are algorithmically downplayed. Even though many support this comment, and thus restore Francken's face, quite a few TopFans reject his apology based on the fact that he did not come clean himself, but was forced by ‘t Scheldt, and because he still tried to find excuses for his behavior in terms of extenuating circumstances he articulates as ‘hard times’, ‘a lot of stress’ and ‘very drunk’. It is exactly in such comments of his Top Fans that we see that Francken's face is now assigned a negative value, and that his offering did not save his face to at least part of his fan base. But, importantly, those negative comments do not receive as many positive reactions from his fans, and are thus made less visible by the algorithms. That is, Facebook also contributes to the image of ‘acceptance of the apology’ in displaying the vanity metrics: 8.4k people give it a thumbs up, 1.7k reward his post with a heart, and 1k feel sorry for him. The semiotic presentation of uptake in the form of those metrics produces the idea that his apology is accepted, and that his digital face is restored among a majority of his fans. The principle of popularity (van Dijck 2013:13) is thus a central ingredient in restoring one's digital face. The apology needs positive uptake to be seen as successful.

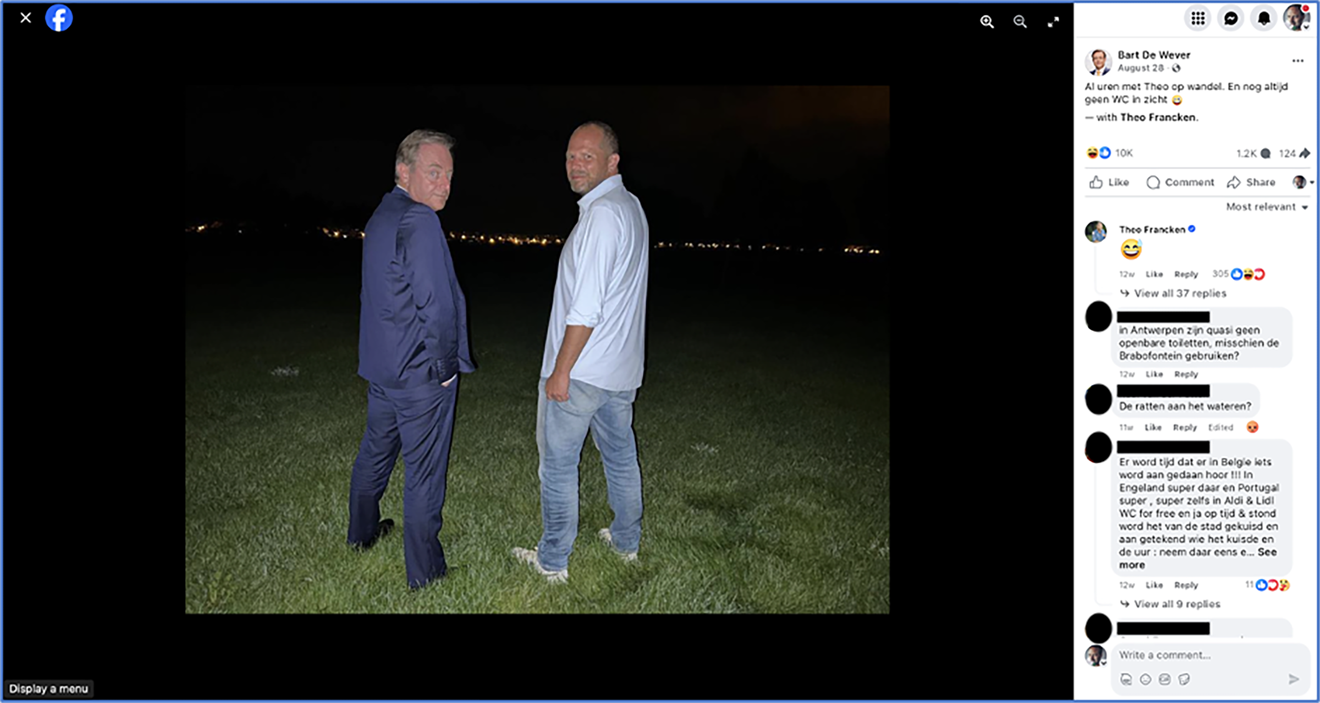

In a digital attention economy, the construction and reconstruction of a politician's face also becomes a communicative opportunity. This becomes clear if we look at the post that Bart De Wever, the chairman of N-VA, released on August 28, 2023 on his Facebook page and Instagram account and which was shared by Francken on his own social media (see Figure 2). In this post, a different type of offering to save Francken's face is used: the joke. We see De Wever and Francken standing with their backs to the camera—suggestive of them peeing—accompanied with the tongue in cheek comment ‘Already walking for hours with Theo. And still not a toilet in sight ☺’. The joke minimalizes the incident—it presents it as truly banal. The fact that the chairman makes the joke communicates that the party is still behind Francken and, as such, restores the collective face of the party of which Francken is still part. Also, if any politician could pull off this joke, it is De Wever, who is by many—even his political adversaries—regarded as a political giant. This post also marks the end of the story. The Flemish public broadcasting company mentions the incident once, on August 27th. In the legacy newspapers, De Standaard and De Morgen, the incident was mentioned as a fait divers on the weekend, but not as a huge political scandal. In De Standaard, it was mentioned in a few lines in a special ‘ironic’ section of the newspaper dedicated to rumors in politics. In sum, Francken's apologies and De Wever's tongue-in-cheek joke succeeded in restoring face and killing the story.

Figure 2. Tongue in cheek Instagram post by Bart De Wever.

Digital face in a hybrid media system

This case study shows that face-work in a post-digital environment is a sociotechnical assemblage: claiming a line is done in relation to the directive force of digital media, and the digital cultures it facilitates. Digital media platforms are clearly more than a decorum, with associated sociocultural conventions, for interaction. Platforms not only invoke social normativities, they actively steer discursive behavior, make it visible or invisible (Bucher Reference Bucher2018). Digital interaction consists of interaction with humans and interfaces and algorithms at the same time. Digital discourse is thus produced in relation to an algorithmically steered attention economy. Successful politicians are politicians that succeed in producing face that resonates with a substantial part of the electorate. This ‘face’ is not an inherent quality—it is not to be found in the input discourse alone—it is produced in dialogue with others and in dialogue with the dominant media logic. Altheide (Reference Altheide2023:1), for instance, argues that Trump should be understood as ‘an actor who has taken advantage of the logic of the contemporary communication environment’. That has always been what successful politicians do—they use the latest media to their advantage. Reagan, Berlusconi, and Trump are emblematic examples of larger changes in the media environment, or more concretely in the dialectic between media and politics (Maly Reference Maly and Chun2022b).

Analyzing the digital face of politicians forces us to look at the construction of that face through discursive action in relation to media infrastructures and cultures. Central in my analysis of political digital face is the poiesis-infrastructure nexus (Arnaut, Karrebaek, Spotti, & Blommaert Reference Arnaut, Karrebaek;, Spotti; and Blommaert2017:13). The poiesis-infrastructures nexus focuses the attention of researchers on understanding human activity as creative social interaction embedded in infrastructures and allows us to better grasp ‘how creative activity is both enabled and constrained by the conditions in which it takes place’ (Calhoun, Sennett, & Shapira Reference Calhoun, Sennett and Shapira2013:197). The poiesis-infrastructure nexus ‘envisages the double process of emergent normativities and sedimentations, on the one hand, and the creative and material production processes unsettling these on the other hand’ (Arnaut et al. Reference Arnaut, Karrebaek;, Spotti; and Blommaert2017:15). Politics in algorithmic culture should thus not be understood as passive nodes, but as ‘interactional actors embedded, but never fully conditioned by the systems that organize that experience’ (Van Nuenen Reference Van Nuenen2016:19). The construction of a political digital face is realized in relation to the digital interaction order, but also in relation to the hybrid media system (Chadwick Reference Chadwick2017).

The algorithmically driven attention economy is now a dominant element of the social situation, and thus has an important impact on the specific forms political digital discourse acquires. The attention economy is not just grabbing our attention; the interplay between humans and platforms results in new discursive genres and practices, new cultures and new social formations (networked audiences, affective audiences, micro-population, and/or light communities). Small stories are an example of this digital interaction order. Platforms stimulate users and politicians, in general, to share their life in a breaking news format. With the emergences of those small stories, we also see the rise of small scandals—scandals that undermine politicians’ face and demand urgent face-work if they want to minimize the political effects.

In sum, the directive algorithmic and design power of platforms co-constructs digital interaction, and thus digital cultures and societies around the globe. As a result, this sociotechnical attention economy has reconfigured not only how we produce and consume digital culture but also the actual structure of societies around the world. Platforms—through the sociotechnical assemblage they facilitate—influence and steer how we—politicians included—interact and, as such, it steers worldviews, informs cultural practices and shapes affective audiences.