Suicide constitutes a major killer among youth.1 Suicide attempts are risk factors for subsequent suicide attempts, and repeated suicide attempts further increase the risk of both additional suicide attempts and suicide.Reference Pagura, Cox, Sareen and Enns2 Little research has been done among adolescents on the differences between those with a single suicide attempt (SSA) and those with multiple suicide attempts (MSA), especially in Latin America.Reference Pagura, Cox, Sareen and Enns2,Reference Speed, Drapeau and Nadorff3 SSA is an important predictor of MSA, because in most studies 16–34% of subjects have a subsequent suicide attempt within the first 1–2 years after their initial suicide attempt.Reference Mendez-Bustos, de Leon-Martinez, Miret, Baca-Garcia and Lopez-Castroman4 Therefore, it is of the utmost relevance to determine which factors are associated with MSA.Reference Pagura, Cox, Sareen and Enns2,Reference Speed, Drapeau and Nadorff3 It has been theorised that the experience of suicide attempt increases the susceptibility of the individual to both MSA and suicide.Reference Guo, Wang, Wang, Li, Gong and Zhang5,Reference Spirito and Esposito-Smythers6 This may be because the barrier or taboo against suicide is removed after the initial suicide attempt; thus, individuals may perceive suicide as a more viable option when stressors arise.Reference Spirito and Esposito-Smythers6

Based on previous research,Reference Khan, Rahman, Islam, Karim, Hasan and Jesmin7 risk factors for MSA were conceptualised into psychosocial distress factors, negative social or environmental factors, and health-compromising behaviours. Some research comparing SSA and MSA among adolescents in USA and Australia found that psychosocial distress factors (depression,Reference Walrath, Mandell, Liao, Holden, De Carolis and Santiago8,Reference Rosenberg, Jankowski, Sengupta, Wolfe, Wolford and Rosenberg9 comorbid health risks,Reference Rosenberg, Jankowski, Sengupta, Wolfe, Wolford and Rosenberg9 being a victim of physical assaultReference Rosenberg, Jankowski, Sengupta, Wolfe, Wolford and Rosenberg9 and history of sexual abuseReference Vajda and Steinbeck10), negative social–environmental factors (lower social support of family, friends or non-family adults,Reference Merchant, Kramer, Joe, Venkataraman and King11 and lack of mental healthcare following the first suicide attemptReference Defayette, Adams, Whitmyre, Williams and Esposito-Smythers12) and health risk behaviours (externalising disorder,Reference D'Eramo, Prinstein, Freeman, Grapentine and Spirito13 sexual risk behaviour,Reference Rosenberg, Jankowski, Sengupta, Wolfe, Wolford and Rosenberg9 substance useReference Rosenberg, Jankowski, Sengupta, Wolfe, Wolford and Rosenberg9,Reference Vajda and Steinbeck10,Reference D'Eramo, Prinstein, Freeman, Grapentine and Spirito13 and serious self-mutilationReference Esposito, Spirito, Boergers and Donaldson14) were associated with MSA. However, most of these investigations had a selection bias owing to only using in-patient or emergency room department samples. Therefore, their results cannot be generalised to the general community,Reference Pagura, Cox, Sareen and Enns2 and no such studies have been conducted in Latin America. Developmental trends may also influence the transition from SSA to MSA. For example, in a 90-country study, younger adolescents attending school (13–15 years old) had different associations with suicide attempt than older adolescents attending school (16–17 years old).Reference Campisi, Carducci, Akseer, Zasowski, Szatmari and Bhutta15

Prevalence

In Latin America, the prevalence of suicide attempt in the past 12 months among adolescents attending school (13–15 years old) was 17.9% in Andean countries, followed by 15.7% in Southern cone countries, including Argentina, and 13.2% in Central American countries.16 Current alcohol use and lack of peer support increased the risk of suicide attempt across the subregions in Latin America.16 In a study among adolescents attending school in Bolivia, Costa Rica, Honduras, Peru and Uruguay, bullying victimisation was highly associated with suicide attempt.Reference Romo and Kelvin17 Suicide mortality rates in the region of the Americas from 2001 to 2008 showed an increase among young people in five countries, including Argentina.Reference Quinlan-Davidson, Sanhueza, Espinosa, Escamilla-Cejudo and Maddaleno18–Reference Bella, Acosta, Villacé, López de Neira, Enders and Fernández20 In Argentina, rates of suicidal ideation and suicide planning significantly increased among girls but not among boys from 2007 to 2018; this could be in part attributed to a higher decline in parental support among girls.Reference Peltzer and Pengpid21 In the 2012 Global School-based Student Health Survey (GSHS) in Argentina, parental support was found to be protective against suicide attempts.Reference Santillan Pizarro and Pereyra22 In different studies among youths admitted to hospital in Argentina, major precedents of suicide attempts were previous attempted suicides,Reference Bella, Fernández, Acevedo and Willington23,Reference Bella, Fernandez and Willington24 behavioural and conduct disorders,Reference Bella, Fernández, Acevedo and Willington23–Reference Bella, Fernández and Willington25 depression,Reference Bella, Fernández and Willington25 labile emotional balance and exacerbated impulsiveness,Reference Pugliese26 and family disorders (family structure and functioning, single-parent family and family relationships).Reference Bella, Fernandez and Willington24,Reference Pugliese26 In an investigation among adults with suicide attempts in a public hospital in Argentina, poor family functioning was identified as a risk factor for suicide attempt.Reference Burgos, Narváez, Bustamante, Burrone, Fernández and Abeldaño27

Aims and objectives

Considering this background, the present study tried to fill the identified gap by researching the differences between adolescents with MSA versus SSA using a large school-based sample from Argentina. By examining sociodemographic factors,Reference Merchant, Kramer, Joe, Venkataraman and King11,Reference Pengpid and Peltzer28 psychosocial distress factors including multiple adverse experiences,Reference Khan, Rahman, Islam, Karim, Hasan and Jesmin7,Reference Pengpid and Peltzer28–Reference Liu, Zhang and Sun31 negative social or environmental factors (such as low parental or peer support)Reference Merchant, Kramer, Joe, Venkataraman and King11,Reference Pengpid and Peltzer28 and health-compromising behaviours (tobacco use,Reference Pengpid and Peltzer28 bullying victimisation,Reference Koyanagi, Oh, Carvalho, Smith, Haro and Vancampfort32 and soft drinkReference Jacob, Stubbs and Koyanagi33 and fast foodReference Jacob, Stubbs, Firth, Smith, Haro and Koyanagi34 intake), we sought to identify relevant factors that may affect the relationship between MSA and SSA in the general adolescent population in Argentina.

Method

Sample

Publicly available data from the nationally representative cross-sectional 2018 Argentina GSHS were analyzed.35 More details on the study and the data are publicly available on the World Health Organization website.35 Briefly, the main objective of the GSHS was to measure the risk and protective factors of the main non-communicable diseases.

Procedure

A two-stage cluster sample design was used to generate a representative sample of all students in the eighth grade of primary school/polymodal or first year of high school to third year/12th grade polymodal or fifth year of high school in Argentina (age range ≤11 to ≥18 years). At the initial stage, schools were selected with a probability proportional to the size of the enrolment. At the subsequent stage, classes were randomly selected and all students in selected classes were eligible to participate, regardless of age.35 Students completed a self-administered questionnaire in Spanish under the supervision of trained external survey administrators.35 The school response rate was 86%, the student response rate was 74% and the overall response rate was 63%.35 From the total sample of 56 981, we restricted our analyses to those who had a history of suicide attempts during the past 12 months (n = 8507).

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. All procedures involving human subjects were approved by the ethics committee of the Ministerio de Salud y Desarrollo Social de la Nación, and written informed consent was obtained from the participating schools, parents and students.35

Measures

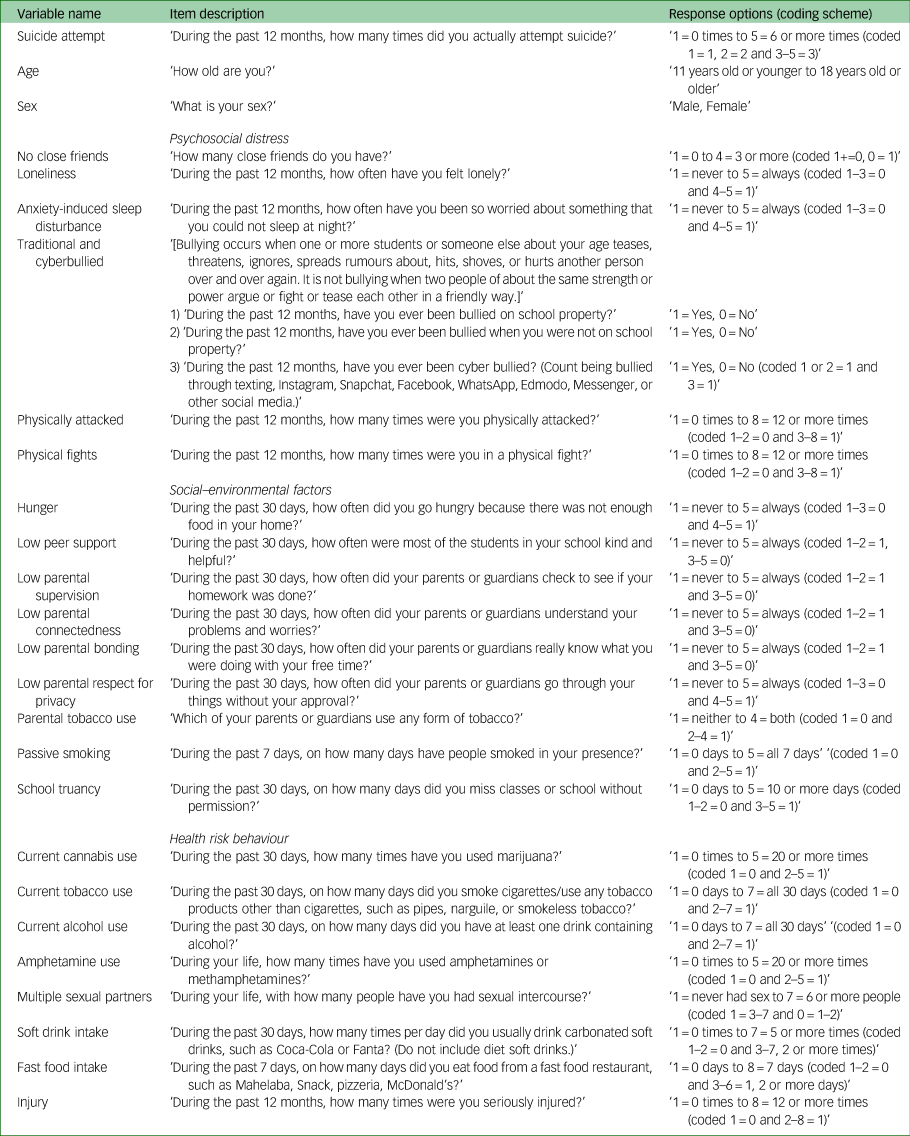

The GSHS questions used are shown in Table 1.35 The GSHS is a sister study of the US ‘Youth Risk Behavior Survey’ for which test–retest reliability has been proven.Reference Brener, Collins, Kann, Warren and Williams36 Moreover, the GSHS questionnaire showed a test–retest agreement of 77% and a Cohen's kappa of 0.47.Reference Becker, Roberts, Perloe, Bainivualiku, Richards and Gilman37

Table 1 Questionnaire items used in this survey

The outcome variable ‘suicide attempts’ was evaluated with the question ‘During the past 12 months, how many times did you actually attempt suicide?’35

Six items were used to assess psychosocial distress: having no close friends, loneliness (mostly or always), anxiety-induced sleep disturbance (mostly or always), bullied (≥1 or 2 days/month), physically attacked (≥1 times/year) and involvement in physical fighting (≥1 times/year). Seven questions were used to assess negative social or environmental factors: experiencing hunger (mostly or always), low (never or rarely) support by peers, parental tobacco use, passive smoking (≥1 day/week), school truancy (≥1 or 2 days/month) and low parental support (never or rarely parental/guardian checking of home work, understanding of problems and worries, ‘really knowing what you were doing with your free time when you were not at school or work,’ and parents/guardians mostly/always go through things. The four parental support items were summed and grouped as high (0–1), moderate (2) and lowest (3–4) levels of parental support (as in previous studiesReference Pengpid and Peltzer28). Eight items were used to assess health-compromising behaviours: current use of tobacco, alcohol and cannabis; fast food intake (≥1 day/week); lifetime use of amphetamines; multiple sexual partners (≥2 sexual partners in lifetime); consumption of soft drinks (≥1/day) and physical injury (≥1/year).

Statistical analysis

STATA software version 15.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas, USA) was used for statistical analyses. Data were weighted for the probability selected and non-response. To test differences in proportions, Pearson's χ2-tests were used. Adjusted logistic regression analyses were applied to estimate independent predictors of MSA versus SSA. History of suicide attempts in the past 12 months were coded here as 1 (two or more times) and 0 (one time). Unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression analyses were used to estimate predictors of MSA versus SSA. The multivariable logistic regression model was adjusted for sociodemographic variables, psychosocial distress factors, negative social or environmental factors, and health-compromising behaviours. Moreover, adjusted logistic regression analyses were applied to estimate associations between the number of psychosocial distress factors, negative social or environmental factors, health-compromising behaviours and MSA versus SSA. This multivariable logistic regression model was adjusted for sociodemographic variables, number of psychosocial distress factors, number of negative social or environmental factors, and number of health-compromising behaviours. Missing values (<1.9% for suicide attempts and <4.3% for all other variables) were excluded, and P < 0.05 was accepted as significant.

Results

Sample and suicide attempt characteristics

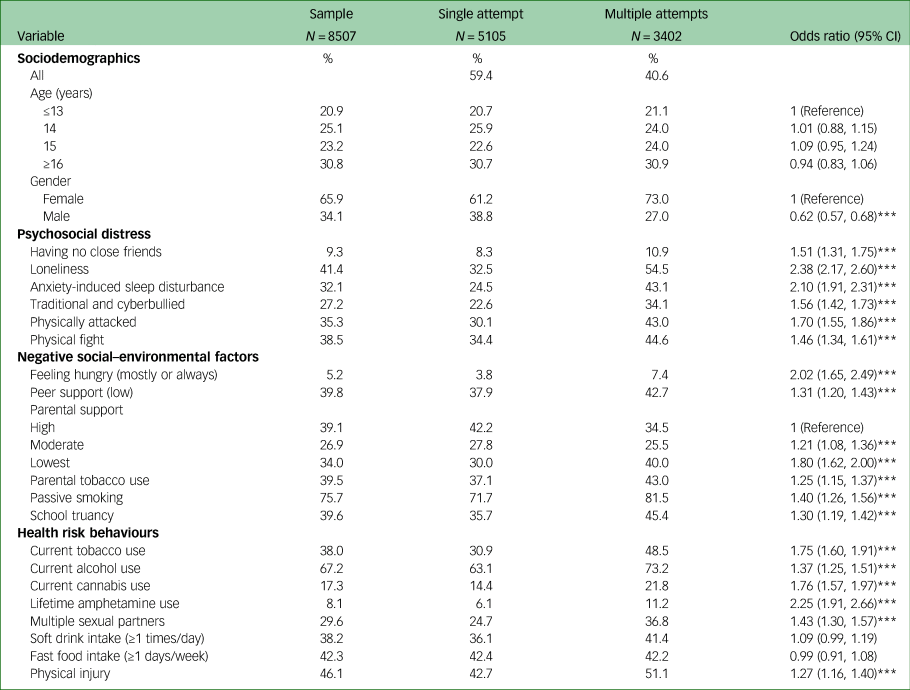

The subsample consisted of 8507 adolescents attending school (mean age 14.8 years, s.d. = 1.3) who had either an SSA (n = 5105, 69.4%) or MSA (n = 3402, 40.6%) during the past 12 months. The majority of the sample (65.9%) was female. Almost one in ten students (9.3%) had no close friends, 32.1% had anxiety-induced sleep disturbance, 35.3% had been attacked, 41.4% were lonely, 27.2% had often been traditionally and cyberbullied and 38.5% had been involved in physical fighting. More than one-third of the students (38.0%) were current tobacco users, 17.3% used cannabis currently, 8.1% had ever used amphetamine, 39.5% had parents who used tobacco, 38.2% consumed soft drinks (≥1 times/day), 42.3% had fast food (≥1 days/week) and 46.1% had a serious physical injury (≥1 times/year). Male students had a lower rate of MSA than female students. When comparing SSA with MSA, the proportions of all psychosocial distress variables, all negative social–environmental factors and six of eight health risk behaviours were higher in students with MSA. Further sample details are shown in Table 2.

Table 2 Sample characteristics and odds ratios of single and multiple suicide attempters among adolescents attending school in Argentina

*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

SSA and MSA among adolescents attending school by sex in Argentina

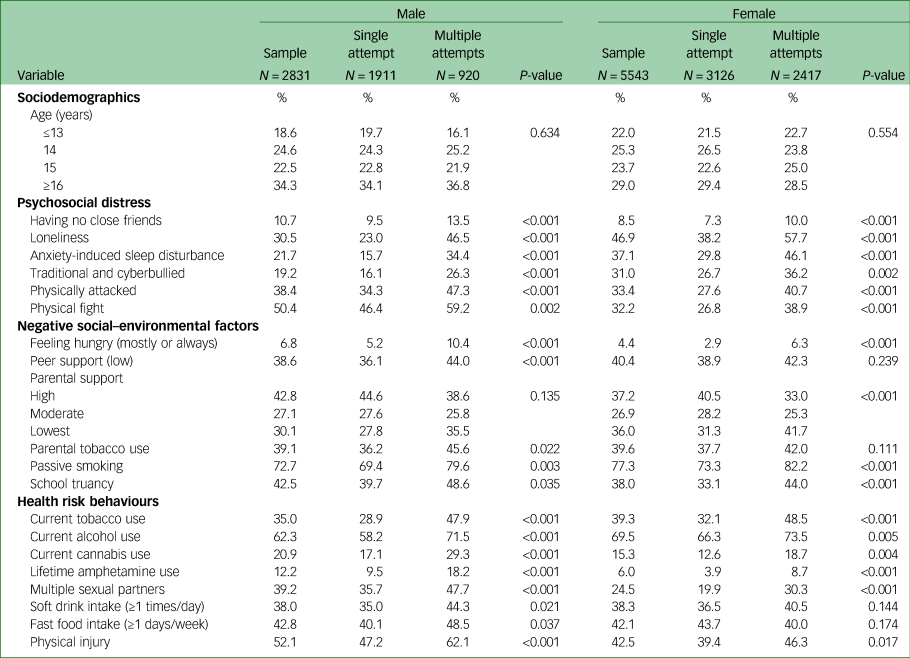

Of the six psychosocial distress variables evaluated, all were higher in individuals with MSA than in those with SSA in both boys and girls. Of the eight health risk behaviour variables assessed, all were higher in MSA than in SSA in boys, and, among girls, six health risk behaviour variables were higher in MSA than in SSA. Of the six negative social–environmental factors measured, among males, five were higher in MSA than in SSA and, among females, four were higher in MSA than in SSA (Table 3).

Table 3 Single and multiple suicide attempts among adolescents attending school by sex in Argentina

Association between single risk factors and MSA

In the final adjusted logistic regression model, compared with participants with SSA, both male and female students with MSA more frequently had no close friends (adjusted odds ratio [AOR]: 1.50, 95% CI: 1.00–2.26 among boys and AOR: 1.52, 95% CI: 1.16–1.56 among girls), reported feeling more lonely (AOR: 2.56, CI: 1.99–3.31 among boys and AOR: 1.74, 95% CI: 1.51–2.02 among girls) and had more anxiety-induced sleep disturbances (AOR: 1.57, CI: 1.20–2.07 among boys and AOR: 1.35, 95% CI: 1.16–1.57 among girls). Furthermore, among female participants, having been physically attacked (AOR: 1.26, 95% CI: 1.08–1.47), having participated in physical fights (AOR: 1.33, 95% CI: 1.13–1.57), having low parental support (AOR: 1.45, 95% CI: 1.23–1.71), current tobacco use (AOR: 1.20, 95% CI: 1.01–1.41) and use of amphetamines (AOR: 1.47, 95% CI: 1.04–2.07) were associated with MSA. Among male students, having multiple sexual partners (AOR: 1.30, 95% CI: 1.01–1.67) was associated with MSA (Table 4).

Table 4 Associations between single and multiple suicide attempts by single risk factors

a Adjusted for sociodemographic factors, and all variables in the table.

b Log likelihood (LL) = 95 460.87, Nagelkerke R2 = 0.23.

c LL = 237 667.98, Nagelkerke R2 = 0.13.

*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Association between multiple risk factors and MSA

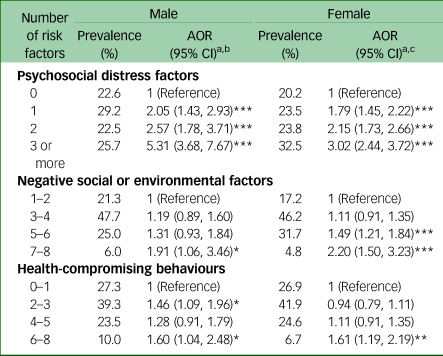

In the final adjusted logistic regression model, among both sexes, compared with participants without psychosocial distress, participants with one, two, three or more psychosocial distress factors had higher odds of MSA. Compared with students with one or two social or environmental risk factors, students with seven or eight social or environmental risk factors had a higher odds of MSA, and compared with students who had zero or one health risk behaviours, students with six or more health risk behaviours had higher odds of MSA (Table 5).

Table 5 Associations between single and multiple suicide attempts by multiple risk factors

a. Adjusted for sociodemographic factors, and all variables in the table.

b. LL = 88 766.15, Nagelkerke R2 = 0.18.

c. LL = 227 797.29, Nagelkerke R2 = 0.11.

*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Discussion

This investigation aimed to estimate psychosocial distress factors, social or environmental factors, and health risk behaviour correlates of MSA versus SSA in adolescents attending school in Argentina. The findings related to psychosocial distress, low parental support and health-compromising behaviour variables associated with MSA versus SSA were largely consistent with those of previous research.Reference Walrath, Mandell, Liao, Holden, De Carolis and Santiago8–Reference Merchant, Kramer, Joe, Venkataraman and King11,Reference D'Eramo, Prinstein, Freeman, Grapentine and Spirito13 Having no close friends, loneliness, and anxiety-induced sleep disturbance, among both boys and girls, were able to differentiate between adolescents with MSA versus SSA. Having been physically attacked, having participated in physical fights, low parental support, current tobacco use and lifetime amphetamine use were able to differentiate between girls with MSA versus SSA. Having had multiple sexual partners was able to differentiate between boys with MSA versus SSA.

Several studiesReference Pagura, Cox, Sareen and Enns2,Reference Mendez-Bustos, de Leon-Martinez, Miret, Baca-Garcia and Lopez-Castroman4,Reference Romo and Kelvin17,Reference Liu, Zhang and Sun31 have shown that having a mental disorder, hopelessness and stressful life events such as interpersonal violence predict MSA. Echoing these findings, the treatment of psychosocial distress factors and reduction of interpersonal violence, including being bullied, are important in the prevention of MSA. In line with some previous research,Reference Defayette, Adams, Whitmyre, Williams and Esposito-Smythers12,Reference Liu, Huang and Liu38,Reference Miranda-Mendizabal, Castellví, Parés-Badell, Alayo, Almenara and Alonso39 we found that female sex and lower socioeconomic status (using food insecurity as a proxy) increased the odds of MSA. However, contrary to some research,Reference Defayette, Adams, Whitmyre, Williams and Esposito-Smythers12 we did not find significant age differences in relation to the prevalence of MSA versus SSA. A previous study among adolescentsReference Defayette, Adams, Whitmyre, Williams and Esposito-Smythers12 that assessed lifetime suicide attempts found that younger age of first suicide attempt was associated with MSA; by contrast, our study assessed only suicide attempts during the past 12 months, which may explain the non-significant age differences in MSA in this study. The preponderance of MSA among girls appeared to be consistent with a previous systematic review showing that females (12–26 years) had a higher risk of suicide attempt.Reference Miranda-Mendizabal, Castellví, Parés-Badell, Alayo, Almenara and Alonso39

Consistent with previous studies,Reference Khan, Rahman, Islam, Karim, Hasan and Jesmin7,Reference Cluver, Orkin, Boyes and Sherr29,Reference Wan, Chen, Ma, McFeeters, Sun and Hao30 this investigation demonstrated that MSA increased with increases in multiple risk factors, possibly confirming a dose–response relationship. We found an association between anxiety-induced sleep disturbance and MSA. Similarly, in a previous studyReference Speed, Drapeau and Nadorff3 among adults, an association was found between the frequency of nightmares and MSA. Knowledge of the variables that are potentially associated with subsequent suicide attempts can be helpful to healthcare providers, who could detect anxiety-induced sleep disturbance, lack of close friends and loneliness to identify MSA risk. Asking about anxiety-induced sleep problems and loneliness may be less threatening than asking about suicidal ideation or intent.Reference Speed, Drapeau and Nadorff3 Furthermore, low parental support was among girls associated with MSA in this study. In the 2012 GSHS in Argentina, parental support was found to be protective against suicide attempts.Reference Santillan Pizarro and Pereyra22 According to a previous trend study among adolescent girls in Argentina, parental support decreased from 2007 to 2018.Reference Peltzer and Pengpid21 The reduction in parental support could be attributed to changes in the family system in Argentina.Reference Binstock, Jayakody, Thornton and Axinn40 Previous studies among adolescents in Latin America16,Reference Romo and Kelvin17 found associations of suicide attempt with current alcohol use, lack of peer support and bullying victimisation, whereas we did not find such associations with MSA in our study.

The limitations of this study include the inclusion of only adolescents attending school, the cross-sectional survey design and the assessment by self-report. Moreover, the GSHS in Argentina did not assess suicide attempts prior to the past 12 months, suicide attempt methods, family history of suicide or help-seeking behaviours for suicidal behaviours. Future studies should assess these variables in order to more comprehensively measure factors differentiating SSA and MSA. Moreover, several concepts were only assessed with single-item questions, which are limited; future research should include full scales, such as those on depression or childhood adverse events. Comparing the demographics of this subsample with the full sample of the GSHS Argentina 2018, we found no age differences (mean age 14.8 years) but a higher preponderance of girls (65.9%) in the subsample compared with the full sample (52.0%). The gross enrolment in secondary schools in Argentina was 108% in 2019.41

In conclusion, psychosocial distress (anxiety-induced sleep disturbance, having no close friends and loneliness) increased the odds of MSA among both sexes. Interpersonal violence, low parental support and substance use among girls, and having multiple sexual partners among boys increased the odds of MSA. Furthermore, among both sexes, a higher number of psychosocial distress factors, social or environmental risk factors, and health risk behaviours increased the probability of MSA. Variables identified may potentially discriminate between MSA and SSA among adolescents in Argentina.

Data availability

The data generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available in the World Health Organization NCD Microdata Repository (https://extranet.who.int/ncdsmicrodata/index.php/catalog/).

Acknowledgements

This paper uses data from the GSHS. GSHS is supported by the World Health Organization and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The data source, the World Health Organization NCD Microdata Repository (URL: https://extranet.who.int/ncdsmicrodata/index.php/catalog), is hereby acknowledged.

Author contributions

All authors fulfil the criteria for authorship. S.P. and K.P. conceived and designed the research, performed statistical analysis, drafted the manuscript, and made critical revisions of the manuscript for key intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript and have agreed to the authorship and order of authorship for this manuscript.

Funding

None.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.