In 1966, the largest U.S. employer was General Motors, and compensation for its workers averaged $40 an hour (in 2016 dollars). The CEOs of big U.S. firms at that time earned about 21 times as much as their average workers. Forty years later, the largest U.S. employer was Walmart, which paid its workers $8 an hour on average, and the CEOs of large companies earned 271 times as much as their employees (Economic Policy Institute 2017). Although less dramatic, parallel developments can be found across the developed democracies. In the span of a single lifetime, the developed political economies have changed dramatically.

Some of those changes are rooted in secular economic developments, driven by technological change, the opening of world markets, and shifting patterns of consumption, which moved employment from manufacturing to services. Those changes have also been deeply affected by dramatic shifts in the economic, social, and regulatory policies that governments deploy in pursuit of economic growth. We can think of this complex of policies as the “growth regimes” that governments implement to secure and distribute economic growth.Footnote 1

The objective of this article is to outline how the growth regimes of the developed democracies have changed since World War II and to explore the contribution that electoral politics has made to those changes. My argument differs from two conventional approaches to such issues. One sees socioeconomic policies as efforts to find efficient means for promoting growth, so that secular economic developments, such as changes in technology and the opening of international markets, become the pivotal drivers of policy. Indeed, many policy makers see their task in these terms, and governments ignore economic developments at their peril. Growth regimes do respond to secular changes in the economy.

Efficiency explanations, however, neglect the political dimensions of the problem, born of the fact that economic policy making has distributive implications and is thus always a conflictual enterprise based on coalition building. There is rarely only one “efficient” response to a given set of economic developments. Conceptions of what policies will be efficient are dependent on bodies of economic doctrines that are contestable and are often debated in terms that are not entirely scientific. Because economic policy making entails coalition building, doctrines are often chosen for their political as well as their economic appeal. The popular versions of these doctrines form the “economic gestalt” of a given era.

The approach of this article also departs from a perspective common in comparative political economy, which sees growth regimes as the outcome of producer-group politics in which segments of labor and capital agitate for policies beneficial to them (for influential works, see Culpepper Reference Culpepper2011; Swenson Reference Swenson1989; Thelen Reference Thelen2014). Producer-group politics clearly matters. Many political parties have ties to segments of labor or capital whose interests they are expected to advance, and the capacities of producer groups to coordinate with each other on endeavors such as wage setting or vocational training provide governments with instruments for economic management. These instruments are important because the number of outcomes that policy makers can target depends on the number of instruments they have at hand. Indeed, scholars have observed that, in some settings, producer-group politics is so influential that all else may be merely “electoral spectacle” (Hacker and Pierson Reference Hacker and Pierson2010, 3).

Yet democratic governments face pressure not only in the arena of producer-group politics but also in the electoral arena, and there are good reasons for exploring the role this political pressure plays in the evolution of growth regimes.Footnote 2 Instead of assuming that this role is always a minor one, we need to understand why electoral politics might be more influential at some times than at others; and, because the electoral arena is a realm in which broad social compromises can be forged, there is value in considering how shifts in that arena affect nations’ capacities to construct such compromises (cf. Offe Reference Offe1983; Przeworski and Wallerstein Reference Przeworski and Wallerstein1982a).

I chart movement in the growth regimes of the developed democracies through three distinctive eras since World War II—an era of modernization, running from 1950 to 1975, an era of liberalization from the early 1980s through 2000, and a subsequent era of knowledge-based growth—and argue that these regimes correspond not only to particular sets of economic circumstances but also to specific electoral circumstances. My overarching claim is that the inclination and capacity of governments to pursue distinctive growth regimes depend on the evolution of electoral cleavages and how they condition partisan electoral competition. This dynamic also affects the relative influence of the electorate and producer groups on policy. In closing, I explore the implications of this analysis for contemporary politics.

This summary belies the fact that these developments are riddled with endogeneity. In each era, secular economic developments and growth regimes condition each other, and both affect the evolution of electoral cleavages. Because several of these factors are usually in flux at any given time, the results cannot be described as equilibria. But this analysis points to the ways in which economies and polities coevolve. Of necessity, the analysis is also somewhat stylized. At any given time, there is significant variation in national growth regimes, which move at different paces and to varying extents along distinctive trajectories conditioned by the institutional structure of different varieties of capitalism (cf. Amable Reference Amable2003; Hall and Soskice Reference Hall and Soskice2001). A more extensive analysis would chart those trajectories, but I focus instead on parallel movements over time to identify commonalities in the processes behind shifts in growth regimes.

An Era of Modernization, 1950–1975

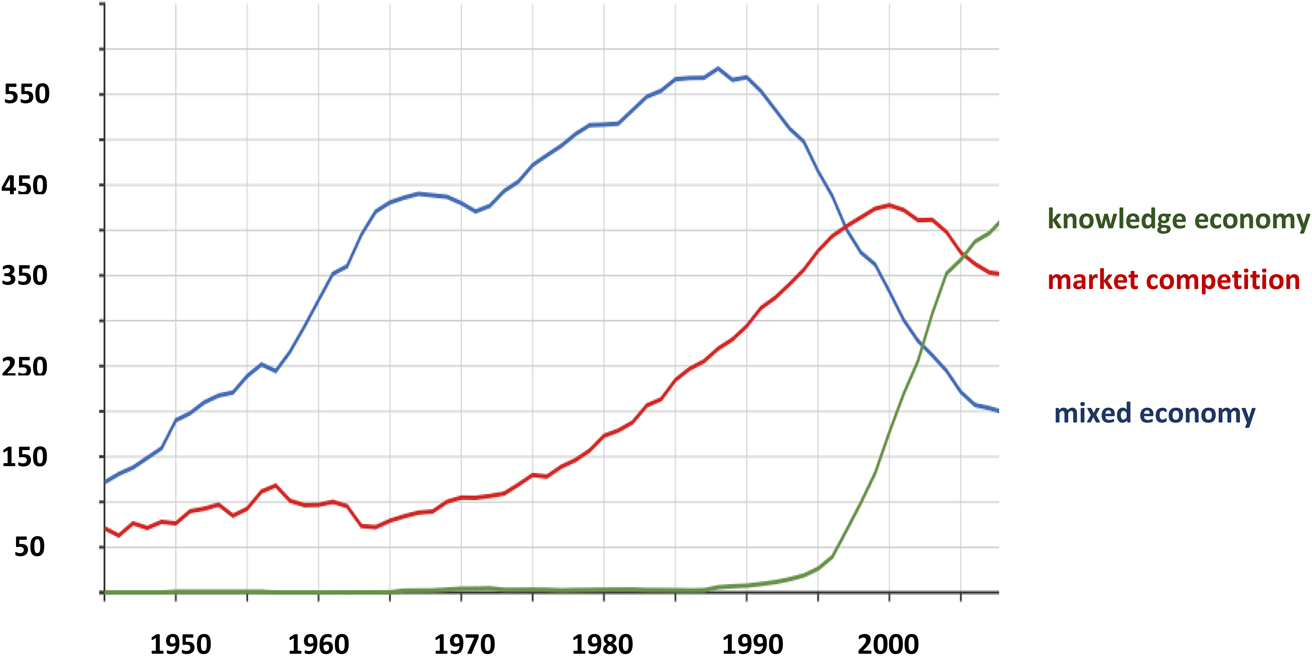

Shortly after World War II, most of the developed democracies entered what might be described as an era of modernization (for overviews, see Hall Reference Hall1986; Shonfield Reference Shonfield1969). Seen in historical perspective, the growth regimes of this era were marked by four distinctive features: (1) relatively assertive state intervention oriented to securing higher levels of investment, (2) demand management along broadly Keynesian lines aimed at ensuring full employment, (3) efforts to promote collective bargaining between employers and trade unions, and (4) the gradual expansion of social insurance programs designed to mitigate poverty and limit social conflict. These are the growth regimes of the “mixed economy,” a term that became central to the economic gestalt of the period (see figure 1).Footnote 3

Figure 1 Frequency of the use of the terms “mixed economy,” “market competition,” and “knowledge economy” in all English-language books, 1945–2008

Note: Google Ngram. Y axis is proportion of references in all English language books where the scale is 50 = .000050%.

Source: Google Ngram

To be sure, there was a good deal of national variation around these themes. In France, a system of indicative national planning brought representatives from business and labor together to develop sectoral investment priorities, backed by flows of funds from nationalized banks, provisions for generalizing wage bargains across sectors, and a statutory minimum wage to which 40% of French wages were eventually tied (Cohen Reference Cohen1977; Zysman Reference Zysman1983). After a burst of nationalizations following the war, the British relied more heavily on active demand management, bolstered by experiments with indicative planning and active industrial policy in the 1960s (Brittan Reference Brittan1971; Leruez Reference Leruez1975). Sweden exploited the coordinating capacities of its trade unions and employers to modernize the economy along lines specified by the Rehn-Meidner model, which used solidaristic wage bargaining in the context of restrained fiscal policies to push firms toward more efficient modes of production, while active labor market policy addressed the consequent unemployment (Martin Reference Martin and Crouch1979; Pontusson Reference Pontusson1992). Wary of an activist state and influenced by ordoliberal rather than Keynesian economic doctrines, West German governments eschewed active demand management and extensive state intervention in favor of building a social market economy. But doing so entailed promulgating dense systems of rules; promoting bargaining over wages, working conditions, and training between employers and newly strengthened trade unions; and the aggressive use of monetary policy to promote exports (Katzenstein Reference Katzenstein1987; Kreile Reference Kreile and Katzenstein1978; Sally Reference Sally2007). In their own ways, each of these countries moved significantly away from the policies of the interwar years to develop the growth regimes of a mixed economy.

The growth regimes of the mixed economy served the needs of a manufacturing economy particularly well (Boyer Reference Boyer1990). Thus, they were especially appropriate for the economic challenges of the 1950s and 1960s, when economies had to be rebuilt after the war and manufacturing remained central to employment. Efforts to manage aggregate demand enhanced the predictability that firms needed to make the long-term investments required for high-volume manufacturing. The regularization of collective bargaining promoted the wage increases that fueled demand for manufactured products, while institutions to coordinate wage bargaining reassured firms that those increases would leave room for the profits crucial to investment (Przeworski and Wallerstein Reference Przeworski and Wallerstein1982b). New international regimes regulating trade and monetary relations promoted the expansion of manufactured exports, increasing the demand for higher levels of investment (Eichengreen Reference Eichengreen, Crafts and Toniolo1996).

Economic conditions alone, however, did not dictate the growth regimes of these years. The socioeconomic policies of democratic governments are also political constructions, responsive to prevailing political conditions. Therefore, we have to ask: what features of politics during the 1950s and 1960s encouraged governments to adopt the policies of a mixed economy?

Disillusionment with the outcomes of earlier economic policy was a crucial background condition. Many voters were repelled by the high levels of unemployment that accompanied the policies of the interwar years, and in the wake of a catastrophic war, both electorates and governments became more willing to experiment with alternatives. The availability of economic doctrines that rendered such alternatives credible was also important; in various countries, the doctrines of Keynes, the Freiburg school, and Rehn-Meidner served that purpose, each offering rationales for new approaches to economic management. If disappointment with past performance provided the motive for change, these doctrines supplied the means for moving beyond past patterns of policy (Hall Reference Hall1989; Reference Hall, Kahler and Lake2013).

But democratic governments also face strong incentives to formulate policies that appeal to the electorate, and the electoral conditions of those years played an important role in pushing governments to implement the more assertive growth regimes of the mixed economy. The two features of electoral conditions that matter the most to such outcomes are which issues are most salient to the electorate at the relevant point in time and the terms in which partisan competition over them are conducted. Those are conditioned, in turn, by the principal cleavages dividing the electorate, defined as the bases on which voters understand their interests and identities to be opposed to those of other groups.Footnote 4 Given that economic policy making also involves coalition building, these cleavage structures have considerable bearing on what coalitions can be constructed.

Cleavage structures emerge both from bottom-up processes of socioeconomic change, which affect the material interests and worldviews of voters, and from top-down processes through which the appeals mounted by political parties incline voters to define their interests and identities in particular ways. The most important feature of electoral politics in this era of modernization was the prominence of a class cleavage, which arrayed voters who saw themselves as members of the working class against others who identified with a more affluent middle class.

This cleavage has its origins in the industrial revolution of the nineteenth century and the socialist movements it inspired, but was sustained during the 1950s and 1960s by large differences between the living conditions of the two classes and the appeals of left-wing parties that emerged stronger after the war (Evans and Tilley Reference Evans and Tilley2017; Knutsen Reference Knutsen2006; Nieuwbeerta Reference Nieuwbeerta1995). As figure 2 indicates, the class cleavage remained prominent in many countries for at least two decades after World War II.Footnote 5 On one side were Social Democratic and Communist parties claiming to speak for the working class and committed to using the levers of state power, including economic planning and the nationalization of enterprises, to achieve full employment. On the other side were Conservative, Liberal, and Christian Democratic parties, which were more representative of the middle class, fearful of state intervention, and committed to securing prosperity through free markets.

Figure 2 Alford index indicating the level of class-based voting, 1945–1990

Source: Manza, Hout, and Brooks Reference Manza, Hout and Brooks1995. The Alford index reports the proportion of the working-class voting left minus the proportion of the middle-class voting left.

The class cleavage had a dramatic influence on socioeconomic policy making. Its prominence made issues of state intervention and social policy highly salient to electoral conflict; in turn, the salience of these issues forced political parties interested in attaining office to find a middle ground: settling on those policies that would satisfy their own core constituents while also drawing votes from their opponents. Conscious that electoral success would require cross-class support, the social democratic parties of Europe met at landmark party conferences from Bad Godesberg to Blackpool, deciding to drop their insistence on nationalization in favor of managing a mixed economy (Crosland Reference Crosland1956). For similar reasons, many Conservative and Christian Democratic parties gradually accepted more active economic management and various forms of industrial intervention as viable strategies for operating a market economy. By suggesting that full employment could be secured via aggregate demand management without any need to nationalize the means of production, Keynesian doctrines were instrumental to this convergence (Hall Reference Hall1989; Przeworski and Wallerstein Reference Przeworski and Wallerstein1982a). Thus, the growth strategies of the mixed economy emerged as a social compromise mediated by electoral politics: they were just interventionist enough to draw support from voters on the center-left but grounded enough in market competition to win votes from the center-right (Offe Reference Offe1983; Przeworski and Wallerstein Reference Przeworski and Wallerstein1982b).

Of course, the policies of each nation were inflected by the relative power of the political left and right. In Sweden, a growth regime based on solidaristic wage bargaining owed much to the dominance of the Social Democrats, whereas an influential Christian Democratic Party built Germany’s social market economy. But virtually all European governments were pushed toward more assertive economic policies and more expansive social policies by a powerful electoral challenge from the political left rooted in the salience of the class cleavage (Huber and Stephens Reference Huber and Stephens2001). As figure 3 indicates, the major movement in economic platforms during the 1950s and early 1960s was convergence toward the left (Manow, Schäfer, and Zorn Reference Manow, Schäfer and Zorn2008).

Figure 3 Support for “free markets” in the platforms of European political parties, 1957–2015

Note: Party positions on the “free market economy”’ index of Lowe et al. (Reference Lowe, Benoit, Mikhaylov and Laver2011) indicating the prevalence in partly platforms of support for a free market economy and market incentives as opposed to more direct government control of the economy, nationalization, or other Marxist goals. Calculated from Comparative Manifesto Project data. Higher values indicate more support for free market positions.Footnote 10

An Era of Liberalization, 1980–2000

The growth regimes of the mixed economy reached their economic apogee and political perigee during the 1970s, as governments struggled to cope with simultaneous increases in inflation and unemployment. Multiple factors contributed to this “stagflation,” but Keynesian policies proved inadequate for addressing it, and the unwieldy income policies that often followed called into question the legitimacy of state intervention (Crozier, Huntington, and Watanuki Reference Crozier, Huntington and Watanuki1974; Lindberg and Maier Reference Lindberg and Maier1985). In short, just as mass unemployment during the interwar years had discredited the policies of that period, the stagflation of the 1970s discredited the interventionist policies of the mixed economy, leaving governments and electorates more open to experimentation with alternative economic formulas. The eventual result was movement toward a new set of growth regimes characteristic of an era of liberalization, which began in the early 1980s and ran roughly to the end of the twentieth century.

If assertive state action had been a theme of the previous growth regimes, those of the new era were built on the opposite principle, namely, that the best way to promote economic growth was to reduce the role of the state in the economy in favor of allocating more resources through competitive markets. The idea that active fiscal policy could be used to secure full employment was superseded by the contention that levels of unemployment were determined by institutional conditions on the supply side of the economy and best addressed by structural reforms to labor and product markets.

Just as nationalization had been a feature of the prior regime, privatizations of public enterprise became a fixture of the new one and a welcome source of government revenue, while the principle that regulation should subordinate market competition to social goals gave way to efforts to intensify competition in all kinds of markets (Centeno and Cohen Reference Centeno and Cohen2012). Public services were outsourced to private contractors to make them more efficient. In Anglo-American economies, radical steps were taken to limit the power of trade unions; even in continental economies, firms gained more flexibility to bargain locally over wages and working conditions. New regulations made temporary and part-time work more feasible, vastly expanding the numbers of people working on time-limited contracts, often in dual labor markets (Palier and Thelen Reference Palier and Thelen2010). After decades in which social insurance had expanded, the 1990s saw successive efforts to reduce replacement rates, limit eligibility periods, and tie the receipt of social benefits to more stringent work requirements, effectively transforming “welfare” into “workfare” in the name of “social investment” (Bonoli Reference Bonoli2005; Morel, Palier, and Palme Reference Morel, Palier and Palme2012; Pierson Reference Pierson2001).

The pace and extent of these shifts varied across countries (Thelen Reference Thelen2014). The pioneers were Britain and the United States under Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and President Ronald Reagan (Gamble Reference Gamble1994; Riddell Reference Riddell1991). France moved in similar directions after 1983, but the German Wende of Helmut Kohl amounted to little until the high-profile Schröder reforms of the early 2000s (Fitoussi Reference Fitoussi1993). As the indicators for liberalizing initiatives in figure 4 suggest, movement in much of Europe toward the new growth regimes was most pronounced during the 1990s. However, a decisive step was taken with the adoption of the Single European Act of 1986, which turned the European Commission into an agent for market liberalization (Jabko Reference Jabko2006).

Figure 4 Liberalizing and deliberalizing initiatives in EU countries, 1975–2015

Source: Fill Reference Fill2018 and Armingeon et al. Reference Armingeon, Baccaro, Fill, Galindo, Heeb and Labanino2019.

Like their predecessors, these new growth regimes responded to secular economic developments that were changing the terms on which growth and employment could be secured. Among the most important was a decline in the share of economic activity devoted to manufacturing relative to services (Iversen and Cusack Reference Iversen and Cusack2000; Wren Reference Wren2013). There had been movement in this direction for decades, but by the end of the 1980s, governments were realizing that, if they wanted to create jobs, those would have to be in services. Because levels of productivity are lower and rise more slowly in many parts of the service sector than in manufacturing, one way to create service-sector jobs was to allow for lower wages; and many governments saw the expansion of part-time positions offering limited wages and fewer benefits as a means of accomplishing that aim (Iversen and Wren Reference Iversen and Wren1998; Scharpf Reference Scharpf, Scharpf and Schmidt2000).

Equally significant, however, was the competition firms faced from newly emerging economies in more open international markets. As value chains became more global and pressure on subcontractors more intense, many firms began to press for more flexible wage and working arrangements, backed up by the increasingly credible threat that employment would otherwise move abroad (Tassey Reference Tassey2014; Thelen and van Wijnbergen Reference Thelen and van Wijnbergen2003). Thus, governments came under intense pressure from business to liberalize labor markets.

The rationale for doing so was provided by economic doctrines, grounded in a “new classical economics” that posited a “natural rate of unemployment” largely impervious to demand management but tractable to deregulatory reforms in labor markets (Dornbusch Reference Dornbusch1990; Stein Reference Stein1981). Using similar rational-expectations logics, monetary policy was said to have few durable effects on the real economy. The corollary was that it should be targeted on inflation and placed beyond the reach of politicians; as a result, many central banks were made more independent during the 1990s.

Although many economists were persuaded by these doctrines, their popularity with policy makers also rested on their political usefulness. Politicians who had been happy to take credit for full employment during the 1960s were anxious to relieve themselves of responsibility for high unemployment in the 1970s and 1980s. Thus, the idea that unemployment resulted from labor-market conditions rather than from failures of economic policy had considerable political appeal. As popular versions of these doctrines filtered into a new economic gestalt, “market competition” became a watchword for the 1980s (see figure 1).

In broader political terms, however, the era of liberalization had problematic effects. Many of the initiatives central to its growth regimes imposed costs on large segments of the population. The privatization of public services pushed many people out of once-secure jobs. Efforts to render wages more flexible, although beneficial to those who might not otherwise have had a job, depressed wages in many sectors. Imposing work requirements on the recipients of social benefits made their lives more difficult, while changes to the tax and regulatory regimes of the 1980s and 1990s delivered large benefits to the wealthy at the cost of people on average incomes. What sorts of political conditions made these moves possible?

Institutional reforms that took responsibility for some sets of policies out of the hands of national governments are one part of the answer. Those reforms gave elected governments a shield behind which to hide their responsibility for unpopular policies, effectively reducing the extent to which growth regimes responded to the electorate. Central bank independence served that purpose, but in Europe the most important moves were those transferring more authority over policy to the European Union, which used its new powers to liberalize markets and constrain budgetary policies within the Eurozone. Although the member states were ultimately responsible for the actions of the European Union, they could and often did blame unpopular initiatives on it (Hall Reference Hall, Culpepper, Hall and Palier2006).

Thus, the role played by electoral politics in the development of the growth regimes of this era was more circumscribed than during the era of modernization. In the context of popular disappointment with economic performance after 1974, neoliberal proposals initially had some electoral appeal, notably in Britain and the United States. But the movement toward neoliberal growth regimes was primarily an elite initiative, led by politicians desperate to revive economic growth in order to retain electoral support, disillusioned with the ability of earlier policies to do so, and faced with increasing pressure from firms for neoliberal forms of regulation (Sandholtz and Zysman Reference Sandholtz and Zysman1989).Footnote 6

Initial moves in neoliberal directions also set in motion an escalating dynamic. As global markets for goods and finance were liberalized and foreign investment became a more important component of overall investment, governments came under greater pressure to meet the demands of firms to reduce regulation and make labor cheaper or more flexible, lest jobs and capital flow elsewhere. Corresponding steps to weaken the labor movement lent further momentum to neoliberal initiatives by altering the balance of power in the industrial relations arena (Baccaro and Howell Reference Baccaro and Howell2017).

How did the electoral politics of the 1980s and 1990s permit governments to move toward neoliberal growth regimes? Once again, the shape of electoral cleavages was relevant. The liberalizing policies of this era were facilitated by the declining salience of the class cleavage and the growing salience of a cleavage over values.Footnote 7 By shifting the terms on which parties could assemble coalitions and thus the incentive structures of partisan competition, these developments facilitated a new convergence to the right in economic platforms and limited the inclination of mainstream parties to resist neoliberal initiatives in the name of a defense of the working class.

By the early 1980s, fewer people were voting along class lines, and mainstream political debate was couched less frequently in class terms (see figure 2). Thirty years of prosperity and evolving occupational structures had already reduced the electoral salience of the class cleavage (Clark and Lipset Reference Clark and Lipset2001). As technological change pushed semiskilled workers out of manufacturing and into low-paid services, the coalition of interests that once united the skilled and semiskilled working class in manufacturing began to unravel, opening up rifts between labor market “insiders” in relatively secure jobs and “outsiders” in more precarious positions (Iversen and Soskice Reference Iversen and Soskice2015; Rueda Reference Rueda2005). However, political path dependence was also important. The previous growth regimes eroded the material insecurity once central to working-class mobilization, and after the social programs of the welfare state were firmly in place, social democratic parties found themselves without a distinctive political mission.

At the same time, a new values cleavage, separating people with cosmopolitan (or postmaterialist) values from those with more traditional attitudes, became increasingly salient (Inglehart and Welzel Reference Inglehart and Welzel2005; Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt and McGann1997). To some extent, this change was a result of the success of the earlier growth regimes. The prosperity of the 1960s era shifted the attention of younger generations away from material concerns toward a focus on the environment, self-fulfillment, and human rights (Inglehart Reference Inglehart1990). Over time, cosmopolitan values came to encompass gay rights and support for open borders, whereas people with traditional values had stronger concerns about immigration, law and order, and the protection of a familiar national culture (Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Martin Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008). The numbers of people with cosmopolitan values grew as tertiary enrollments increased and younger generations replaced older ones, since a college education promotes cosmopolitan values. Those values are typically most often held by younger people with tertiary education, often in socio-professional occupations, whereas traditional values remain prevalent among older people with lower levels of education in routine occupations (Kitschelt and Rehm Reference Kitschelt and Rehm2014).

The shifting electoral opportunities offered by the growing salience of this new cleavage ultimately gave social democratic parties the capacity and incentives to move their economic platforms to the right, in line with growing demands from business and economists for market liberalization (Mudge Reference Mudge2018). Partly to compete with Green parties rising on their left flank in the 1980s and 1990s, social democratic parties also became exponents for cosmopolitan values. This stance on values gave these parties a basis for distinctive electoral appeals that did not rely on their economic platforms, making it more feasible for them to converge with the center right on liberalizing policies. At the same time, the center-left parties’ stance on values drew more educated voters, many of whom benefited more from market-oriented initiatives than their working-class constituents did, and this growing middle-class constituency gave social democratic parties incentives to move to the center-right on economic issues.

As a result, there were some striking electoral developments in the 1980s and 1990s. As figure 5 indicates, mainstream parties began to emphasize values issues more than the economic issues that had been central to electoral competition in the previous era (Ward et al. Reference Ward, Kim, Graham and Tavits2015). By the 1990s, many social democratic parties were drawing more of their votes from the middle class than from the working class (Gingrich and Häusermann Reference Gingrich and Häusermann2015). Party positions, which had converged toward the left on economic issues during the 1950s and 1960s, began to converge toward the right during the 1990s, often based on changes in the positions of social democratic parties (see figure 3; Iversen Reference Iversen2006). The outcomes of these changes were visible in the policies of Tony Blair, Lionel Jospin, Bill Clinton, and Gerhard Schröder. Of course, these shifts in position eroded even further the electoral salience of the class cleavage (Evans and Tilley Reference Evans and Tilley2017).

Figure 5 Changes over time in the relative prominence of economic and cultural issues in the party manifestos of Western democracies

Note: Proportion of references to each type of issue in party manifestos weighted by party vote share in the most recent election for each country. Source: Comparative Party Manifesto Dataset.Footnote 11

In sum, if electoral competition was a key driver behind the growth regimes of the mixed economy, as well as the vehicle for a social compromise between the working and middle classes, the electoral conditions of the 1980s and 1990s militated against a clear-cut class politics, providing permissive conditions for political elites to respond to calls from economists and firms for economic liberalization. Electoral conditions shifted the balance of influence over policy away from the electoral arena toward producer-group politics, supplying the background conditions that moved electoral politics in this era closer toward “spectacle.” Because capital usually has more influence in producer-group politics compared to electoral politics, where the principle of one-person-one-vote gives workers some numerical advantages, that shift also altered the balance of power between capital and labor: the core conflict endemic to modern capitalism (Culpepper Reference Culpepper2011; Offe and Wiesenthal Reference Offe and Wiesenthal1980; Schmitter and Streeck Reference Schmitter and Streeck1986). Neoliberal reforms that weakened the bargaining power of trade unions inside the producer-group arena in this period multiplied the power of capital even further (Baccaro and Howell Reference Baccaro and Howell2017).

An Era of Knowledge-Based Growth – and Political Uncertainty, 2000–the Present

In the opening decades of the twenty-first century, secular economic developments are again shifting the terms on which economic growth and employment can be secured. As the fruits of a revolution in information and communications technology now joined to advances in artificial intelligence diffuse, the viability of many businesses has become dependent on the facility with which they can adopt the new technologies, presaging what can be described as an era of knowledge-based growth (Brynjolfsson and McAfee Reference Brynjolfsson and McAfee2014; Iversen and Soskice Reference Iversen and Soskice2019).

In principle, these developments should be inspiring new growth regimes; certainly, the importance of doing so is widely acknowledged. The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD; 1996) declared more than two decades ago that “knowledge is now recognised as the driver of productivity and economic growth, leading to a new focus on the role of information, technology and learning in economic performance,” and the number of popular references to the “knowledge economy” has risen exponentially since the 1990s (see figure 1). Many governments have increased enrollments in tertiary education to expand the provision of human capital for the knowledge economy, and some have increased funding for research and development or venture capital to gain footholds on the technology frontier (OECD 2017b; 2017c). These efforts have been most successful where governments have been able to engage employer organizations and trade unions in them (Ornston Reference Ornston2013; Schnyder Reference Schnyder2012).

However, it is far from clear that the political conditions that would enable the movement to effective new growth regimes are in place. In many respects, the period since the early 2000s resembles the interregnum of the 1970s, when poor economic performance created political turmoil but new growth regimes had yet to emerge. Stagflation was the main problem in the 1970s. The economic problems of the current era are different. Except for the deep recession of 2008–9, rates of growth have been modestly positive across the OECD, and inflation remains subdued. Instead, the parallel failures of the contemporary era turn on the uneven distribution of the fruits of that growth and on the rising levels of material insecurity on which it has been built.

These failures are primarily a legacy of the previous growth regime. Over the past four decades, income inequality has increased significantly, both across the entire income distribution and within its lower half (OECD 2017a). Between 1975 and 2011, the average wage share in nine leading democracies declined from 65% to 56% of the national product; between 1985 and 2007, the proportion of workers on temporary, rather than durable, labor contracts in the developed economies almost doubled from 8% to 15% (ILO 2012; OECD 2015).

The advent of a knowledge economy is exacerbating these insecurities. As new technologies eliminate the need for labor dedicated to routine tasks, many countries’ occupational structures have polarized; people who once had decently paid routine jobs are being forced into lower-paid positions, often offering services to those with the skills to take highly paid jobs (Autor and Dorn Reference Autor and Dorn2013; Oesch and Menés Reference Oesch and Menés2010). In some regions, many people have not recovered from large losses of income and employment suffered in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis.

More precarious forms of employment and stagnating incomes have fueled widespread political discontent, which is most intense among people in routine occupations and in regions where manufacturing jobs have been hit hard by technological change or import competition (Algan et al. Reference Algan, Guriev, Papaioannou and Passari2017; Colantone and Stanig Reference Colantone and Stanig2018; Foster and Frieden Reference Foster and Frieden2017). For many years, that discontent simmered beneath the surface of a seemingly placid politics, perhaps because some people accepted the ideologies of an era that attributed economic hardship to the limitations of the individuals suffering from it, while many of the most aggrieved simply stopped voting (Mair Reference Mair2013).

In recent years, however, that accumulating discontent has burst into the open. A majority of EU citizens now think that life will be worse for their children than it has been for them, and barely 19% express any confidence in political parties (IPSOS 2017). This discontent has found a voice in parties of the populist right and radical left, whose vote share in legislative elections has doubled since the turn of the century to about 20% of the European electorate, at the same time that the share going to established parties of the center left and center right has declined (Heino Reference Heino2018).

In some countries, radical parties have gained momentum from rapid increases in immigration or recent experiences of austerity (Rodrik Reference Rodrik2018). Many in the working class have been drawn to radical right parties by their stance on values issues, most notably immigration. However, the rise of those parties has been facilitated by a shift in the terms of partisan competition. Until the early 2000s, radical right parties campaigned on traditional values joined to right-wing economic platforms opposed to state intervention, higher taxes, and social spending. Those economic platforms drew votes from small employers, but had limited appeal for many workers. But over the past decade, many of these parties have moved to the left on economic issues, promising better jobs and social protection to their supporters (albeit not to immigrants) to be secured, if necessary, by trade protection (Harteveld Reference Harteveld2016; Rovny Reference Rovny2012). As a result, radical right candidates now have more appeal for working-class voters, and intense conflict over values threatens to drive a wedge through the uneasy coalitions between working-class and middle-class voters on which center-left and center-right parties have come to depend (Oesch and Rennwald Reference Oesch and Rennwald2018). In effect, the terms of working-class defense are being renegotiated.

Thus, the electoral arena is again fractured and in flux, and it remains uncertain whether it will support new growth regimes appropriate to a knowledge economy. Mainstream political parties face a strategic conundrum, making at least three scenarios plausible.

One would see social democratic parties move farther left on economic issues, on the premise that much of the ire currently directed at immigrants can be redirected toward the inequalities of capitalism. This is the gambit advocated by supporters of Jeremy Corbyn in Britain and Bernie Sanders in the United States. The idea is that more radical socioeconomic policies will wean the working class away from parties on the radical right or left. But this is a risky strategy because its success depends on rendering economic issues more salient than values issues to a working-class electorate, while retaining the support of middle-class voters on values rather than economic issues. If this strategy were to succeed, it might usher in state-led transitions toward a knowledge economy, based on free tertiary education, universal income benefits to support continuous education or self-employment, and more stringent regulations forcing firms to improve wages, benefits, and working conditions.

A second scenario sees an electoral arena fragmented among many different groups without overriding cleavages. In that context, as Iversen and Soskice (Reference Iversen and Soskice2019) argue, significant segments of the working class may be attracted to centrist economic policies that foster a knowledge economy, because they will recognize that such policies best serve their own aspirations or those of their children. This support may provide enough votes to allow mainstream parties to implement new growth regimes built around more funding for education, research and development, and infrastructural investment without necessarily increasing state intervention. Employees in medium-skill positions in the service sector seem the likeliest to join the more affluent beneficiaries of the knowledge revolution in such a coalition, because their educational levels give them a foothold in the knowledge economy and sympathy for the cosmopolitan values that most center-left and center-right parties still promote (Kitschelt and Rehm Reference Kitschelt and Rehm2014).

In many respects, this is the most plausible scenario. It reproduces key elements of a status quo in which the leaders of center-left and center-right parties have defended open markets and the European Union against the trade protection and Euro-skepticism often popular on the edges of the political spectrum (see figure 6; Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2018). The election of Emmanuel Macron to the French presidency in 2017 on the ruins of the Socialist Party epitomizes this scenario. But it is vulnerable to the tides of fortune: barely one-quarter of French voters still express confidence in Macron. And this scenario threatens to turn a substantial segment of voters who see themselves as losers from the global knowledge economy into a permanent minority.

Figure 6 Intensity of opposition to (+) and support for (-) European integration in West European party platforms circa 1975, 1992, and 2010

Source: Comparative Manifesto Project Dataset.Footnote 12

We can also envisage a third scenario in which the relatively fluid electoral politics of the present gives rise to a new globalization cleavage. Proxied most directly by education, this cleavage would pit voters with relatively high levels of education that confer both cosmopolitan values and favorable job prospects in a global knowledge economy against voters with less education who are, therefore, more inclined toward traditional values and more apprehensive about the threats such an economy poses to their livelihood.

This political division is already apparent in Western democracies, and there are several reasons for thinking it might congeal into a durable cleavage. For one, this division is particularly potent because it aligns conflicts of economic interest with conflicts about values that are closely associated with people’s social identities (Bornschier Reference Bornschier2010; Gidron and Hall Reference Gidron and Hall2017; Häusermann and Kriesi Reference Häusermann, Kriesi and Beramendi2015; Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2018). In that respect, this divide mirrors the class politics of the 1950s and 1960s, which was never entirely about material interest. Class politics then was also a form of identity politics: many workers voted for social democratic parties, not simply out of economic interest, but because those parties claimed to speak for a “working class” with which they deeply identified (cf. Achen and Bartels Reference Achen and Bartels2016). In addition, the technological revolution that inspires the occupational disruption at the root of this political divide is far from complete, and there is more economic discontent to come. The “creative destruction” that Schumpeter (Reference Schumpeter2008) associated with continuous economic innovation can also bring creative destruction to the polity.

In this case, radical parties speaking for one-quarter to one-third of the electorate might become prominent fixtures in the electoral politics of the developed democracies, where they would pose strategic dilemmas for mainstream parties, potentially impairing their capacities to enact new growth regimes. In systems of proportional representation, parties of the center left and center right may have to negotiate uneasy coalitions with radical parties to govern – potentially limiting the extent to which they can promote innovation, social investment, and free trade, rather than simply providing traditional forms of social or industrial protection.Footnote 8 Alternatively, centrist parties of the left and right might form “grand coalitions” with each other. Those coalitions may be able to promote new growth regimes, but experience suggests they will have a short half-life, because the absence of a mainstream opposition drives disgruntled voters toward the extremes. In majoritarian systems, radical parties find it hard to survive, but even there a globalization cleavage could split mainstream parties apart, reducing their capacities to make the difficult decisions required to respond to contemporary economic challenges.

In short, neoliberal policies and contemporary economic developments have disorganized electoral politics across the Western democracies, yielding a moment of radical openness whose economic and political outcomes are far from certain. Moreover, we cannot predict such outcomes based solely on calculations about material interest, because rapid socioeconomic changes have rendered many people’s interests ambiguous and contemporary politicians are locked in a partisan struggle to redefine the political identities that people at many places within a fissiparous electorate will assume. This is the context in which new growth regimes for the knowledge economy will have to be forged, but in many countries, the form they will take has yet to be decided.

Conclusion

Building on wide-ranging literatures, I have argued that the growth regimes of the postwar democracies have moved through three distinctive eras in response to economic changes and the shifting currents of electoral politics, whose most important feature is their cleavage structures. While devoting less attention to producer-group politics, which deserves a treatise of its own, I have argued that shifts in cleavage structures affect the balance of influence between electoral and producer-group politics. My point is not that growth regimes are determined by electoral politics alone, but that this politics conditions them in ways that comparative political economists should not ignore.

Electoral politics deserves attention, however, not only because of its impact on growth regimes but also because it is one of the principal vehicles for the social compromises on which the effectiveness and stability of democracy depend. In this context, the question of who speaks for whom and with what force in electoral (and producer-group) arenas assumes importance, and postwar growth regimes reflect the impact of changes along those dimensions.

The growth regimes of the era of modernization emerged as a social compromise between political parties acting, often explicitly, on behalf of different social classes in contexts where social and economic issues stood at the forefront of the electoral agenda.Footnote 9 Those compromises yielded policies aimed not only at securing economic growth but also at mitigating many of the inequalities associated with the operation of market economies. By contrast, the growth regimes of the era of liberalization emerged from processes of negotiation in which the voices of social classes were more muted because electoral cleavages and corresponding party strategies had changed. In that context, producer-group politics, where business interests held the upper hand, assumed greater importance, and the era saw widespread increases in income inequality and economic insecurity.

Today, we are seeing a concerted protest from below about what those neoliberal growth regimes have yielded. This protest is disorganizing party politics and calling into question the ability of the developed democracies to forge new social compromises that are both conducive to growth within a knowledge economy and socially inclusive in how they distribute the fruits of that growth. There is much at stake here, because a failure either to secure growth or to distribute it equitably might well threaten the legitimacy of democratic political systems.

Some contemporary dilemmas follow from the extent to which electoral conflict over values issues, including immigration and ethnonational cultural defense, has been superimposed on conflict over economic issues. As values-oriented conflict intensifies, the electoral coalitions of many mainstream political parties that might once have been able to promote new growth regimes are being pulled apart, with working-class voters defecting to the radical right while middle-class voters drift toward Green parties, Liberal splinter groups, or candidates on the radical left (Oesch and Rennwald Reference Oesch and Rennwald2018). Moreover, as economic issues recede in electoral importance, so does the potential for forging comprehensive social compromises focused on them.

Some might hope that candidates on the populist right will emerge as the new tribunes for working people, but experience to date suggests that they are unlikely to be effective at promoting inclusive growth. In some countries, they have simply used populist appeals as a smokescreen for neoliberal policies propitious only for some segments of business. In others, they have advanced social benefit schemes that are aimed mainly at social protection, rather than social investment, which are thus unlikely to augment countries’ capacities for knowledge-based growth (see Beramendi et al. Reference Beramendi, Häusermann, Kitschelt and Kriesi2015).

Others hope that median voters will swing election outcomes in favor of mainstream parties committed to relatively inclusive forms of knowledge-based growth. But, as I have noted, those parties are much weaker than they once were, notably in electoral systems based on proportional representation; and there are serious questions about whether median voters still favor inclusive policies, given the divisions of economic interest that have appeared between labor market insiders and outsiders (Rueda Reference Rueda2005). Therefore, rule by the median voter could leave sizable minorities who believe they are “losers” in the global knowledge economy locked out of effective electoral representation, and the presence of permanent minorities threatens the quality and ultimately the stability of democracy.

Thus, what is at stake in contemporary electoral politics is not simply the shape of future growth regimes but also the capacities of the developed democracies to preserve the allegiance of their citizens amidst profound economic turmoil. Responding to that challenge calls for efficient solutions to current economic problems and for social compromises that can be recognized as socially just both by those who gain more and those who gain less from them.