Introduction

Across European countries, the labour market prospects of many ethnic minorities are still unfavourable today. In the Netherlands, Moroccans (8.0 per cent), Turks (8.5 per cent), Surinamese (5.9 per cent), Dutch Antilleans (9.0 per cent), and other minorities from non-western (9.2 per cent) and western (5.5 per cent) origins represent the highest shares in unemployment, compared with 3.3 per cent among Dutch natives (Statistics Netherlands, 2021a).Footnote 1 However, they also tend to work more often for lower wages and based on flexible work arrangements (Bolhaar et al., Reference Bolhaar, de Graaf-Zijl and Scheer2018; Andriessen, Reference Andriessen, Vassilopoulou, Brabet and Showunmi2019; Strockmeijer et al., Reference Strockmeijer, de Beer and Dagevos2020).

Since 2004, the Netherlands has maintained a generic work-first-oriented support – even though there are differences between ethnic groups (i.e. unrecognised qualifications, vocational skills, and cultural dissimilarities).Footnote 2 The public support imposes strict job-search obligations – with benefit sanctions in case of non-compliance with these obligations – monitored by case manager meetings, and offers job application workshops and education mediation, but with only limited skill investment, cf. other European countries.Footnote 3

Work-first policies prioritise labour market attachment on the premise that any job is better than none to minimise the depreciation of human capital associated with unemployment (de Grip and van Loo, Reference de Grip, van Loo, de Grip, van Loo and Mayhew2002). Its strategic objective prioritises the earliest possible option for work, centralising the job-search process. The rationale of work first assumes that people’s skills acquisition automatically recommences once they start working again (see Bruttel and Sol, Reference Bruttel and Sol2006). In practice, however, many ethnic minorities follow a vicious circle of precarious work interspersed with periods of unemployment or inactivity.

The lack of requirements set by the public employment services for post-unemployment jobs partially explains this vulnerability, particularly the extent to which individuals’ skills match the skills required for jobs and whether employers provide career growth opportunities. This shortcoming often results in dim chances to advance to permanent contracts and to work in better-paid positions compared to the native Dutch population (Kanas and van Tubergen, Reference Kanas and van Tubergen2009; Gracia et al., Reference Gracia, Vázquez-Quesada and van de Werfhorst2016; Statistics Netherlands, 2021b; Hussein, Reference Hussein2022). Our concerns are voiced about the lack of skill investment during work-first support insufficiently addressing the discrepant labour market barriers (i.e. statistical discrimination towards specific ethnic groups, educational attainment, and availability of social resources in their network).

There is a large-scale private sector-initiated employment programme, the ‘Philips Employment Scheme’ [Philips Werkgelegenheidsplan (WGP) in Dutch], in which investing in relevant work experience and vocational training is an explicit goal. Philips – known for its household appliances, lighting products, and healthcare technology – works closely together with the Public Employment Services to tear down labour market barriers for different vulnerable groups of unemployed and partially disabled people, with ethnic minorities as one of their primary target groups (e.g. Peijen and Bos, Reference Peijen and Bos2022; Peijen and Wilthagen, Reference Peijen and Wilthagen2022).

The WGP offers participants one to two years of work experience at the statutory minimum wage. The work-experience job comes with on-the-job, vocational and informal training possibilities (Supplementary Material S.1). All participants undertake compulsory courses on career competencies, professional network building, and job application skills (i.e. CareerSKILLS and JOBS). These courses aim to enable participants to capitalise on career opportunities better and help them be more resilient against future challenges (e.g. job loss). The WGP offers Dutch language courses to participants with language deficits to work more appropriately with current and future colleagues. A vital element is that participants are encouraged to search for jobs in the meantime and have a notice period of only one week to facilitate a swift job-to-job transition and prevent locking-in effects (see van Ours, Reference van Ours2004).Footnote 4

We expect that, because of human-capital investments and signalling effects, WGP participants with a minority background are increasingly likely to achieve sustainable employment – higher employment levels and employment on competitive salaries – than similar minorities entitled to work first. The current study is interested in the post-unemployment careers (up to ten years later) of a selective group of people with a minority background remote from the Dutch labour market (i.e. Moroccan, Turkish, Surinamese, and Dutch Antillean, other non-western, western origin).

The register data used in the current study provides a powerful tool for identifying a comprehensive control group and significantly better treatment predictions. Our matching procedure is based on a large number of pre-treatment covariates, such as a two-year labour market history and geo-linguistic characteristics. If a long-term effect for the WGP can be observed, we are interested in whether better-established wage matches following either intervention explain these long-term labour market returns. This relationship between short and long-term returns in the context of labour market interventions with different investment and time horizon strategies has hitherto not been scrutinised in the literature.

In the sociological literature, much emphasis is placed on analysing ethnic inequality, but analysis of how policy measures may reduce this inequality is rather the exception. Previous studies show, with most being field experiments, that ethnic minorities receive lower call-back rates than the native population (Birkelund et al., Reference Birkelund, Heggebø and Rogstad2017; Thijssen et al., Reference Thijssen, Coenders and Lancee2021). We take a different approach by showing how a human capital-based programme may better close the gap for these unemployed ethnic minorities with the regular labour force, not the native population. Our interest goes to the mixed effects of the WGP, and work-first support among ethnic groups, since comparisons between low and high-investment strategies for ethnic minorities are understudied (e.g. de Hek and de Koning, Reference de Hek and de Koning2020).

It is seen in international studies that work-first policies remove benefit recipients from benefits quickly. In contrast, training and private-sector employment programmes may have minor short-term effects (one year later) but more medium and long-run effects (two-to-three years later) on employment outcomes instead (Abbring et al., Reference Abbring, Berg and Ours2005; Greenberg et al., Reference Greenberg, Deitch and Hamilton2009; de Koning et al., Reference de Koning, de Hek, Mallee, Groenewoud and Zwinkels2015; Card et al., Reference Card, Kluve and Weber2018; Fervers, Reference Fervers2021). However, inconsistent with the literature above, the WGP increased participants’ short-term employment probabilities by 18 per cent one year later (Gerards et al., Reference Gerards, Muysken and Welters2014). The WGP is an interesting case due to the combination of direct employment with formal vocational training, which differs from the more common targeted-wage subsidies in the literature (see Bredgaard, Reference Bredgaard2018).

Other studies that evaluated human capital interventions mainly focused on short-term employment outcomes, such as exit rates and post-unemployment wages (e.g. Card et al., Reference Card, Kluve and Weber2018; Grunau and Lang, Reference Grunau and Lang2020). Concerning the balance between workers’ skills and the skills required for jobs, other scholars had to rely on experimental data observing employees’ perceived job fit and employers’ ratings of job candidates (e.g. Liechti et al., Reference Liechti, Fossati, Bonoli and Auer2017; van Belle et al., Reference van Belle, Caers, De Couck, Di Stasio and Baert2019; van Hooft et al., Reference van Hooft, Kammeyer-Mueller, Wanberg, Kanfer and Basbug2021; Wesseling, Reference Wesseling2021). Contrariwise, since we got access to every individual in the Dutch labour force (1999-2016), we predict expected wage levels using the information on salaries and characteristics of jobs and the individual itself. These predictions will form the baseline for measuring competitive employment levels, which means people’s earning potential, regardless of ethnic background, in a long-term perspective by monthly comparing these expected wages with the actual wages. This operationalisation would give us an insight into the extent to which the ethnic employment gap is closed by either of these two labour market interventions.

Theoretical background

The following section discusses whether and how theoretical and empirical insights into human capital (Becker, Reference Becker1964) and signalling effects related to either statistical discrimination (Arrow, Reference Arrow1971) or individuals’ acquired and adjustable characteristics (Spence, Reference Spence1973) support the causal mechanisms affecting career development for vulnerable ethnic minorities in either of these two labour market interventions.

The long-term impact of the WGP over that of work first

As earlier noted, work-first policies prioritise the earliest possible option for work. The idea is that any unemployed person is ready for work and that any job that follows unemployment can function as a stepping stone to better careers (Gash, Reference Gash2008). No matter how precarious this job might be, no matter how the working tasks of jobs match people’s skills, and whether the employer provides career growth opportunities

As such, work first herewith ignores today’s jobs’ vocational requirements (Eichhorst and Marx, Reference Eichhorst and Marx2021; Mattijssen et al., Reference Mattijssen, Pavlopoulos and Smits2020), along with the scarring and stigma effects of ethnic minorities that remain unabated without skill investment (Gangl, Reference Gangl2006). Explanations often point to information uncertainties of employers about the potential productivity of job candidates to be retrieved from résumés (Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Saporta and Seidel2000; Midtbøen, Reference Midtbøen2015). Employers’ concerns can be based on human capital grounds, such as educational attainment, work experience and competencies, but also often based on discriminatory grounds related to statistical discrimination towards an ethnic group’s expected productivity (Heath and Cheung, Reference Heath and Cheung2007).

Following the theoretical considerations of Spence (Reference Spence1973) and Arrow (Reference Arrow1971), the employment gaps in résumés combined with a foreign name may confirm employers’ doubts about a specific ethnic group regarding their productive capabilities and potential language deficits (Zschirnt and Ruedin, Reference Zschirnt and Ruedin2016; Damelang et al., Reference Damelang, Ebensperger and Stumpf2020; Lippens et al., Reference Lippens, Vermeiren and Baert2022; Ruedin and van Belle, Reference Ruedin and van Belle2022). As such, the disadvantage for ethnic minorities may aggravate over time due to the unhealed scarring effects, given the lack of skill investment in work-first support and post-unemployment jobs (Birkelund et al., Reference Birkelund, Heggebø and Rogstad2017). With a view to post-unemployment jobs, the trouble is that the impending sanctions induce the unemployed to become less selective in choosing jobs, decreasing their reservation wage. In particular, people close to and after benefit exhaustion are vulnerable to the growing share of precarious work (Caliendo et al., Reference Caliendo, Tatsiramos and Uhlendorff2013; Been and de Beer, Reference Been and de Beer2022).

In the long term, work first renders large numbers of ethnic minorities into precarious or poorly matching jobs on fixed-term contracts unexposed to career growth opportunities. In the Netherlands, workers on flexible labour contracts generally participate less in employer-funded training than those with permanent contracts (Fouarge et al., Reference Fouarge, de Grip, Smits and de Vries2012; Koster and Benda, Reference Koster and Benda2020), adversely affecting their adaptability to the labour market’s changing demands. Thus, the scars of past unemployment would not simply heal once people list this kind of work experience in their résumés. Their disadvantage persists or may worsen (Birkelund et al., Reference Birkelund, Heggebø and Rogstad2017; Fauser, Reference Fauser2020; Hoven et al., Reference Hoven, Wahrendorf, Goldberg, Zins and Siegrist2020).

In contrast, human capital programmes postpone integration into the labour market by first levelling up people’s skills in line with labour demand. As such, programmes attempt to reduce prospective employers’ possible concerns about job candidates’ productivity. This approach is more time-consuming due to the (in)formal training opportunities and individual coaching provided (see Borghouts-van de Pas et al., Reference Borghouts-van de Pas, Bosmans and Freese2021). Still, it is supposed to yield favourable long-term returns because it either solves or manages the problem that stands in the way of sustainable careers.

In this spirit, WGP participants gain relevant work experience in a temporary job at Philips that resembles a regular job without postponing labour market integration but with essential skill-building opportunities. Research shows that employer-based interventions (e.g. temporary wage subsidies) are more successful in getting the unemployed back into the labour market than pure training interventions (e.g. vocational classroom training). In addition, employer-based interventions appear to be way more effective than public-sector/non-profit direct job creation (Gerfin et al., Reference Gerfin, Lechner and Steiger2005; Sianesi, Reference Sianesi2008).

Because Philips is among the top twenty-five favourite employers in the Netherlands, its business name on participants’ résumés may be associated with higher performance and training standards. Therefore, the work experience gained during the WGP may be more appealing to Dutch employers, at least compared with the standards of post-unemployment jobs supposedly found by those entitled to work first. Participation in any labour market intervention may signal unproductivity, nonetheless. However, it appears that when employers expect job candidates to need such additional support, as, for instance, ethnic minorities and long-term unemployed, they are less likely to interpret participation in such interventions negatively (Liechti et al., Reference Liechti, Fossati, Bonoli and Auer2017; Auer and Fossati, Reference Auer and Fossati2018; Liechti, Reference Liechti2019; van Belle et al., Reference van Belle, Caers, De Couck, Di Stasio and Baert2019).

Overall, the human capital investment of the WGP is, by default, higher than during work first. Therefore, it is less likely that ethnic minorities remote from the labour market entitled to work first only are provided with this kind of skill investment in their post-unemployment jobs. On the other hand, human capital investment and the signalling effect of working for a reputable company may positively influence employers’ decision-making. This trajectory may initially slow down labour market entry but supposedly yields more favourable long-term returns for WGP participants’ career development. Following these arguments, we postulate that (Hypothesis 1): Unemployed people with a minority background who participated in the WGP establish higher employment (Hypothesis 1a) and competitive employment (Hypothesis 1b) than other unemployed people with a minority background entitled to work first ten years after leaving either intervention.

Different time horizons of strategy

The long-term impact of work experience is contingent on situations where performance information is carried along with individuals, arising from work experience, further education, and on-the-job training (Rosenbaum, Reference Rosenbaum1979). The work experience and skills gained in the employment programme resembling a regular job are no exception. In the case of internal job mobility, performance assessments and further training at current employers are crucial. In contrast, in the event of external job mobility, this information needs to be generated in résumés by listing more predictive productivity signals, such as work experience, skills, and competencies (DiPrete and Eirich, Reference DiPrete and Eirich2006; Thijssen et al., Reference Thijssen, Coenders and Lancee2021).

The different time horizons of strategy are tightly related to strategic objectives that the unemployed or WGP participants need to achieve by performing outlined tasks. Work first’s pushing mechanism aims for the earliest possible placement in the labour market, with case managers closely monitoring job-search efforts. This strategy remains unchanged in future job loss, which explains the vicious work-welfare cycle people end up with (Mattijssen et al., Reference Mattijssen, Pavlopoulos and Smits2020). Philips, by contrast, puts the unemployed back to work through the WGP and aims to align skills to the business’s needs first. Human capital programmes must substantially reduce employers’ concerns before the intervention is completed to prevent people from precarious work – the first blow is half the battle. Otherwise, the strategic objective of the WGP is no different from that of work first.

Alternatively, Thijssen et al. (Reference Thijssen, Coenders and Lancee2021) found that ethnic minorities do not receive higher call-back rates when recording predictive productivity signals in résumés (e.g. grades, performances, and social skills). However, it is unclear from their study whether these signals show either domestic or foreign-gained skills, which may be vital for reducing employers’ uncertainty concerning people’s abilities (see Damelang et al., Reference Damelang, Ebensperger and Stumpf2020). The domestic skills gained at a reputable firm like Philips are expected to be noted by potential future employers as more valuable than skills obtained abroad (see Mergener and Maier, Reference Mergener and Maier2018).

Following Card et al. (Reference Card, Kluve and Weber2018), the different strategies of both labour market interventions yield differential effects on short notice and hence have discrepant outcomes in the long run. We expect that WGP participants can apply for higher-quality jobs that provide more career growth opportunities due to human capital investment. As such, their skills and experience will better match up with the work tasks of these jobs, whilst the post-unemployment jobs for those entitled to work first are likely to remain more precarious. Therefore, we derive the following hypothesis (Hypothesis 2): The long-term impact of WGP participation can (partially) be explained by the higher quality of post-intervention jobs (i.e. wage-match ratio) for WGP participants than for those entitled to work first.

Material and methods

Data and design

Statistics Netherlands’ national register data (CBS Microdata in Dutch) contains micro-level information on the Dutch population’s career and life-course transitions from 1999 to 2017. All former WGP participants (1999-2014) are anonymously identified in the register data, using former participants’ social security numbers in Philips’s registration system.

The Employee Insurance Agency and the local municipalities are responsible for the initial selection of potential participants from the pool of formally registered unemployed and partially disabled unemployed workers using either of the following criteria/guidelines: (1) officially registered as unemployed for six months or longer; (2) formerly early school-leavers; (3) and other disadvantaged groups such as ethnic minorities, refugees, disabled workers, returning mothers, and higher-educated people remote from the labour market. The WGP programme administrators have the final say in selecting their participants from the available unemployed. We focus on this particular group of participants with a minority background.

This group of participants (N = 1,171) consists of people with diverse educational attainments and employment histories across the globe. About 36 per cent are of Moroccan, Turkish, Surinamese, or Dutch Antillean origin, 30 per cent belong to the other non-western ethnic minority group and 34 per cent to the western ethnic minority group. More than half of the participants (54 per cent) started with a low educational degree, 35 per cent had an upper secondary education degree, and only 11 per cent had a professional to university degree.

The labour market histories and welfare dependencies varied among participants (i.e. unemployment benefits and social assistance). Philips’ reference work showed us no specific selection criteria but only guidelines, which involve selection effects (‘cream skimming’) we need to account for in the analysis (see Koning and Heinrich, Reference Koning and Heinrich2013). Most likely, the programme administrators select participants based on their motivation levels unavailable to us as researchers. To overcome potential selection effects, we adopted a quasi-experimental design to eliminate selection bias in our estimates as much as possible.

Propensity score matching

The register data allowed us to construct a work first-entitled control group based on WGP participants’ characteristics to hold the parallel trend assumption. Propensity Score Matching lends itself perfectly to creating a matched sample to perform a difference-in-difference analysis (Stata 16, psmatch2, nearest neighbour 1:1, without replacement, calliper 0.05, and common support).Footnote 5 Every WGP participant is matched to another individual entitled to work first that same year.

We are fully aware that the group of WGP participants potentially is a very selective group of people. The front-door selection of Philips implies that some selection bias might occur, such as language deficits, motivation and personality traits unavailable in the register data. In addition, the data only includes domestic employment and educational attainments, and we could not determine foreign qualifications or reconstruct employment histories abroad. Therefore, we included a two-year labour market history and information about individuals’ last jobs as covariates. In doing so, estimation biases are reduced since we implicitly capture some of the unobserved factors (Caliendo et al., Reference Caliendo, Mahlstedt and Mitnik2017), i.e. personality traits, attitudes, expectations, social networks and intergenerational information).

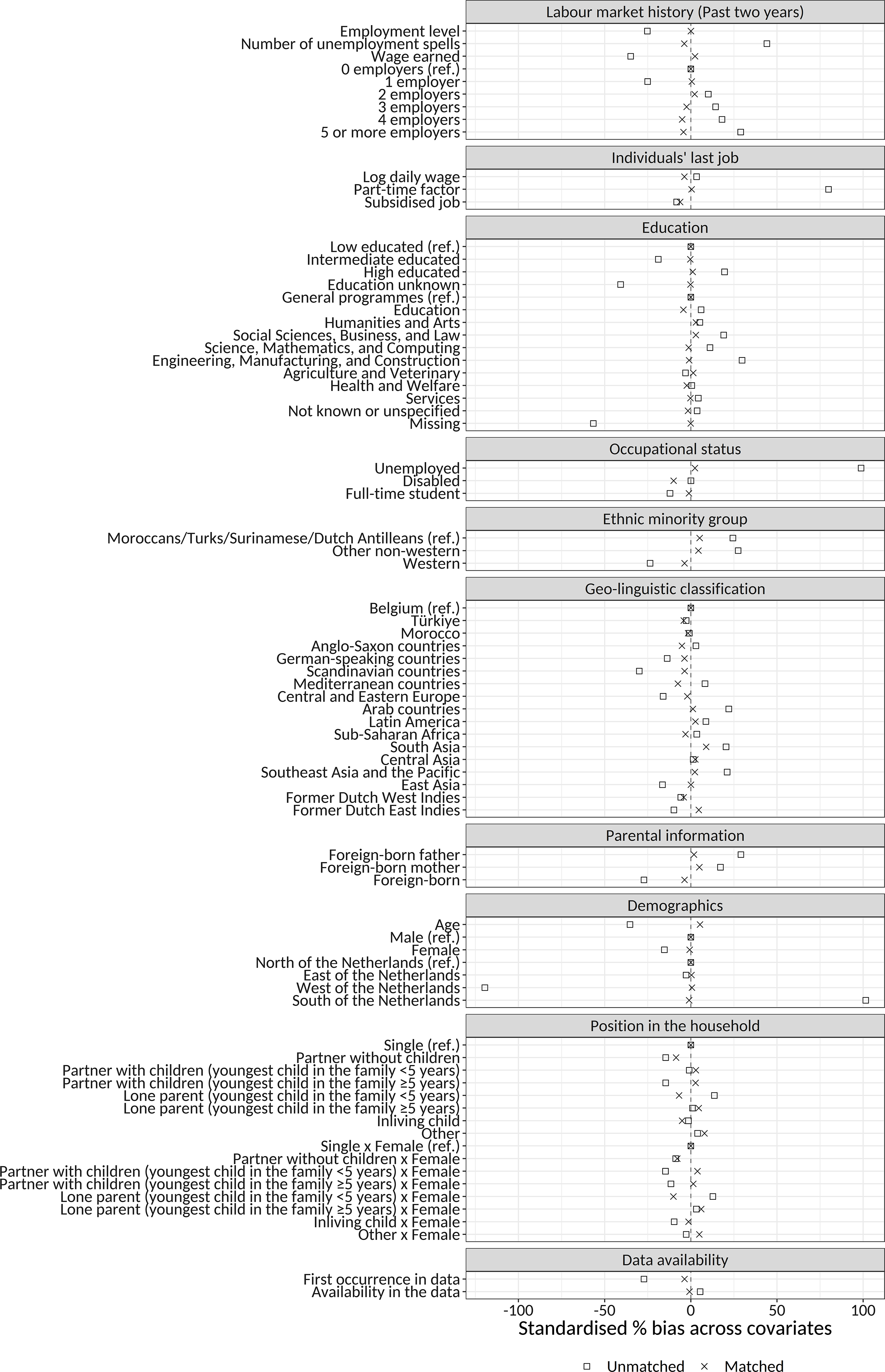

Figure 1 graphically portrays the mean scores of all pre-treatment covariates for WGP participants and unmatched and matched control group members. The standardised percentage bias across covariates shows the reduced heterogeneity in the register data after matching. Please see Supplementary Material S.2 for the theoretical base that yields the choice of every pre-treatment covariate. The geo-linguistic classification categorises people’s migration background based on their language, religion, and country of origin’s political system (Jennissen et al., Reference Jennissen, Engbersen, Bokhorst and Bovens2018). We included the geo-linguistic classification on top of ethnic minority groups because we believed that matching people on only three groups would not do justice to the discrepancies (see Confurius et al., Reference Confurius, Gowricharn and Dagevos2019), particularly within the latter two ethnic groups. In so doing, we again attempt to implicitly capture unobserved determinants of performance associated with a migration background (see Arrow, Reference Arrow1998).

Figure 1. Standardised % bias across covariates before and after matching

Note(s). The abovementioned information entails psmatch2’s pstest output. A negative score indicates that the mean score of that covariate is higher for the control group than for the treatment group, whereas a positive score indicates the opposite. The amount of bias is clearly higher before matching (□). A standardised % bias across covariates close to zero is desired after matching (x) confirming two insignificant tested groups. The required balance checks show insignificant t values after matching, Rubin’s B = 24.3, Rubin’s R = 10 and a (standardised) mean bias 2.3%, confirming the matched sample to be sufficiently balanced.

Please see Table S.2.2.

Source. Statistics Netherlands (1999-2017)

Dependent variables

The first dependent variable is the employment level, defined as the number of employment months in the post-intervention period, including subsidised jobs and regardless of jobs interspersed with periods of unemployment. The second dependent variable is competitive employment, defined as the extent to which an employee’s acquired skills match the position’s required skills, which determines the employee’s productivity level and the salary paid for services rendered (Sattinger, Reference Sattinger1993). Both dependent variables cover the summation of employed months for each individual up to ten years after leaving either labour market intervention, varying from 0 to 120 months, divided by the number of person-year records in the post-intervention period available for every individual in the data, then divided by twelve months.

The register data neither contain subjective information on the job match nor objective information that indicates an occupational status (e.g. ISEI or ISCO). Our skill-match indicator is based on wage matches calculated by dividing the observed natural logarithms of the observed daily wage by the expected daily wage (‘wage-match ratio’). These expected wages are predicted through Heckman’s two-step selection models using all available characteristics of jobs and employees of the total Dutch labour force (N Mean = 15,228,338), regardless of minority background (see Supplementary Material S.3).Footnote 6

Suppose in a month, the observed wage was higher or equal to this expected wage (with a 5 per cent margin on the lower limit), and the job was on a permanent contract (cf. Mattijssen and Pavlopoulos, Reference Mattijssen and Pavlopoulos2019). In that case, we assume that the employer is willing to pay the market wage and matches the individual’s skills and experience. As such, we observe both the wage potential and actual salaries earned. This month gets a value of 1. All successful employment months in the post-intervention period will make the second dependent variable.

Empirical model

Difference-in-difference estimations identify the additional impact of WGP participation over that of work-first entitlement on (competitive) employment up to ten years later (see Supplementary Material S.3). The analyses are performed for each of the following three groups based on the Dutch population distribution: (1) Moroccans, Turks, Surinamese, and Dutch Antilleans; (2) Other non-western; and (3) western.

Fixed-effects linear panel regression models capture the remaining unobserved factors and selection effects as we compare changes within individuals (i.e. individuals’ fixed characteristics). A binary independent variable indicates whether an individual participated in the WGP or was entitled to work first only. An interaction term with another binary independent variable, referring to the post-intervention period, in Equation (1) shows the additional long-term impact of the WGP over that of work first.

Then, we observe whether the change in wage-match ratio for the jobs that follow either intervention, compared with the job before unemployment, accounts for the differential impacts of either intervention on long-term returns. For this purpose, we use the wage-match ratios earlier predicted by the Heckman models (see 3.3). In Equation (2), we propose that the impact of the change in this wage-match ratio (partially) explains these differences in the post-intervention period between WGP participants and the control group. Suppose the observed wage meets or exceeds the expected wage level ( WM it ≥ 1). In that case, we assume that employers are willing to pay the market wage so that the job matches up with an individual’s skills – but it can also be that one either gets overpaid or is over-educated. If the observed wage is below the expected wage level of workers ( WM it < 1), we assume the follow-up job to be on an inferior skill match.

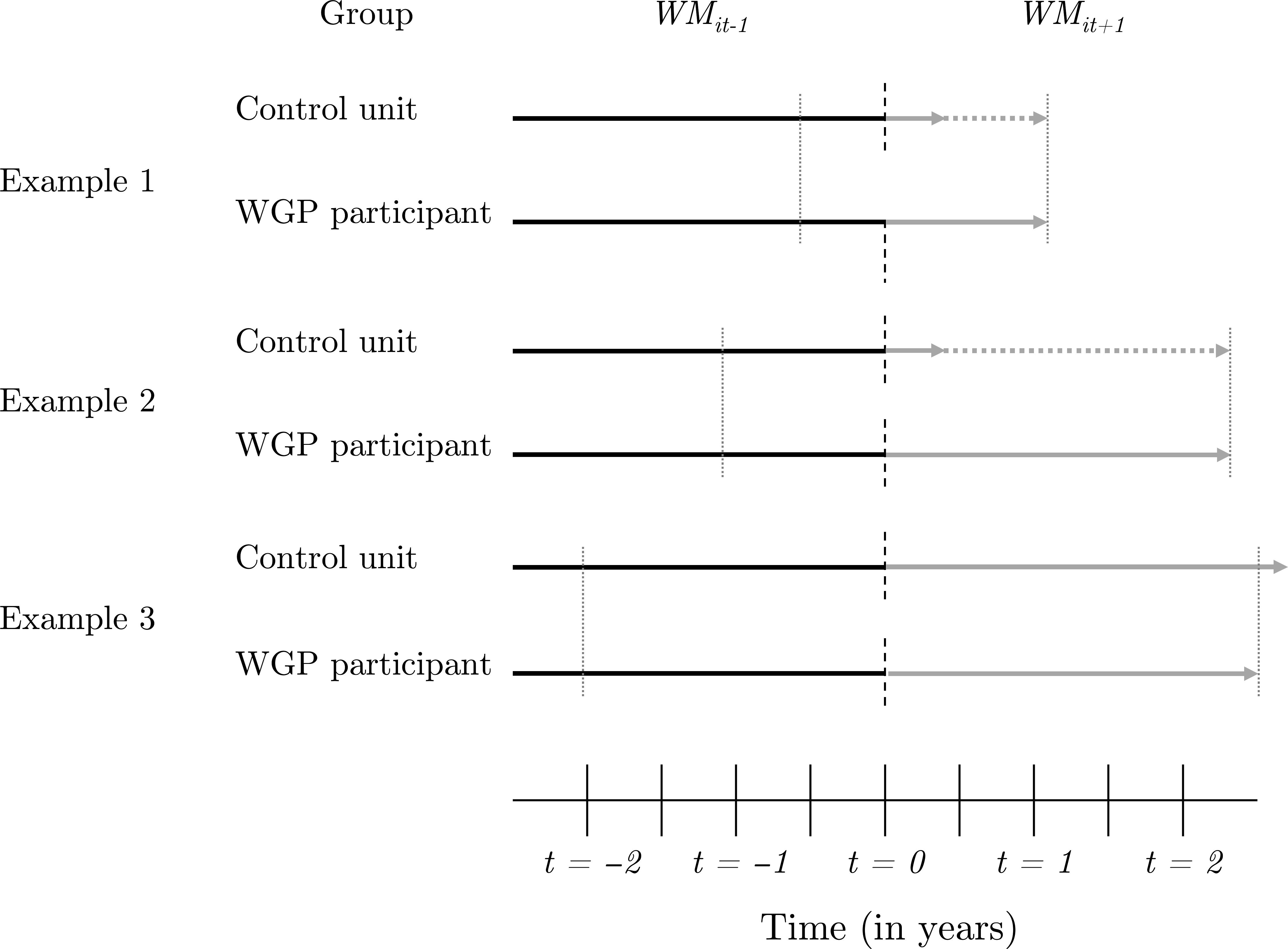

However, as it takes longer to complete the WGP than the average time spent in unemployment and so work-first support, we needed to construct a similar time horizon to determine either intervention’s follow-up job. We believe that we should not look at the job that directly follows work-first support in our wage-match ratio comparison because that would not be a fair comparison with the WGP’s different time horizon of strategy. Therefore, we decided to take each control unit’s wage-match ratio when their statistical twin left Philips, varying from one to twenty-four months after starting the WGP (see Figure 2). Thus, the time at which the value of WM it is taken is not fixed but varies in the sample. In doing so, we respect both interventions’ time horizons of strategy whilst we allow control units to look for jobs with optimal matches in the same timespan as WGP participants get treated. The time horizon includes their unemployment risk after completion – and with work first’s stepping-stone philosophy (‘looking for and changing jobs’) in pursuing sustainable career development.

Figure 2. Creating similar time horizons to compare the wage-match ratio of jobs that follow either work first (control group) or the WGP within matched pairs.

Note(s). Fictitious example. The solid arrows represent the time at Philips (WGP participants) or work first (control units). The dotted horizontal lines for control units represent the time the wage-match ratio is measured based on the WGP’s statistical twin. Please note that the jobs that follow either intervention, denoted by WM it+1 and the vertical lines, do not necessarily mean one year later but are always based on the moment a participant leaves Philips.

The fixed-effects panel structure compares the within-person change in employment associated with the changing wage-match ratio, referring to the wage-match ratio before each intervention (WM it−1) and the job that follows each intervention ( WM it+1 ). The expected wage levels are dynamic in the panel structure and hence change with time-variant characteristics. Take, for instance, educational attainment, age, and sector (see Supplementary Material S.3). The fixed-effects modelling nets out the WGP’s indirect effect through this mediating effect (see Schuessler, Reference Schuessler2017).

The models control for micro and macro-level factors that are measured at intervention entry and completion to avoid any confounding over-time trends – namely, educational attainment; position in the household (including the youngest child in the family) interacted with gender to control for the gendered consequences of unemployment on labour market outcomes (Ng et al., Reference Ng, Tan, Mathew, Ho and Ting2021); residential area (NUTS-3 level); and local unemployment rates (NUTS-2 level) to control estimates for policy changes and cyclical effects as the observation period of 1999-2016 includes two recession periods in the Netherlands (2002-2003 and 2008-2011).

Results

The aim is to examine whether WGP participants of different minority backgrounds establish higher long-term (competitive) employment (Hypothesis 1). If such an effect can be observed, we assess whether this impact can be accounted for by the wage-match ratio on short notice (Hypothesis 2).

Table 1 shows the main effects of the post-intervention period. Models 1, 3, and 5 provide empirical evidence that all people with a minority background entitled to work first improve their long-term employment level (b = 0.07, p < 0.01; b = 0.06, p < 0.05; b = 0.06, p < 0.05). More importantly, the interaction term between WGP participants and the post-intervention period – indicating the additional effect of WGP participation over that of work-first support – shows that other non-westerners and westerners establish higher employment levels than the control group (b = 0.10, p < 0.01; b = 0.11, p < 0.01), except for Moroccans, Turks, Surinamese, and Dutch Antilleans.

Table 1 Unstandardised coefficients on employment and competitive employment, by ethnic group, from fixed-effects regression models

Note(s). ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05, +p < 0.10, robust standard errors in parentheses. Models are controlled for age(-squared), position in the household interacted with gender, local unemployment rate, and the residential area.

Source. Statistics Netherlands (1999-2017)

Models 7, 9, and 11 show the same positive impact of WGP participation for the previously-mentioned groups on competitive employment, albeit modestly (b = 0.06, p < 0.01; b = 0.06, p < 0.01). Note that the main effects of the post-intervention period – representing the labour market returns for the control group – are significantly adverse for all groups (b = −0.05, p < 0.001; b = −0.04, p < 0.01; b = −0.03, p < 0.05). This finding provides empirical evidence for the entrapment hypothesis for those entitled to work first concerning competitive employment and the buffering effect of participating in the employment programme.

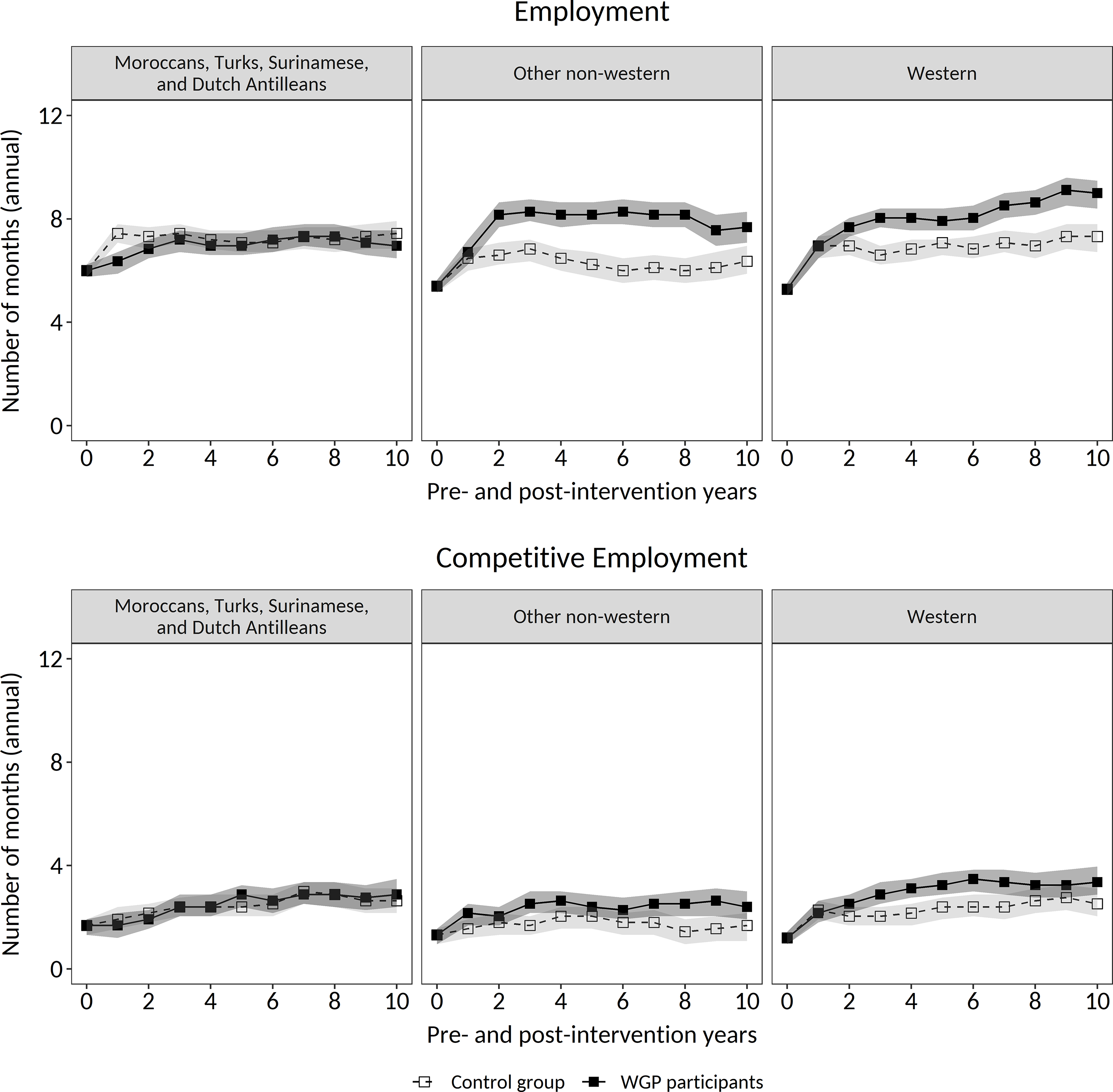

Figure 3 shows the marginal effects plot for the long-term impact of WGP participation compared with work first on (competitive) employment over each post-intervention year. Even though we found similar treatment effects for other non-western and western WGP participants over the entire post-intervention period, this additional model clearly shows mixed career developments among these two ethnic groups. In addition, as we do not have a post-intervention period of ten years for every individual in the sample, we want to be sure that the long-term impact holds over each year of the post-intervention period. WGP participants of western origin have better employment levels at the top – an average annual employment level of 9.12 months in the ninth year – than other non-westerners who structurally stay below a yearly level of eight months. The same goes for competitive employment. WGP participants of western origin experience higher competitive employment – topping an average of 3.48 months in the sixth year – while other non-westerners stay below three months a year. The control groups for every ethnic group show almost no development on both employment variables and remain lower but stable as expected.

Figure 3. Predicted marginal effects of employment and competitive employment over the post-intervention years, from fixed-effects linear regression panel models

Note(s). Shaded bars show the 95%-confidence intervals. A supplemental model predicted the marginal effects by regressing the annual (competitive) employment months and substituting the post-intervention variable for ten post-intervention year dummy variables [cf. Equation (1)] while controlling estimates for the control variables included in the model (Table S.4.1).

Source. Statistics Netherlands (1999-2017)

Once we include the mediator representing the wage-match ratio in Models 2, 4, and 5, the interaction terms between WGP participants and the post-intervention dummy variables become insignificant for other non-western and western minorities. As expected, the estimates of the achieved change in the wage-match ratio explain higher long-term employment levels, appearing to be highly positive (b = 0.25, p < 0.001; b = 0.29, p < 0.001; b = 0.28, p < 0.001).

Concerning competitive employment, in Models 8, 10, and 12, the estimates of the wage match explain higher levels of long-term competitive employment (b = 0.17, p < 0.001; b = 0.13, p < 0.001; b = 0.13, p < 0.001). The interaction terms between WGP participants and the post-intervention period are weakened for all ethnic groups. This finding confirms that the positive long-term impact of WGP participation on employment can (partially) be explained by the wage-match ratios of jobs that follow either of the two interventions. The post-intervention period’s main effects also weaken, but this reduction for those entitled to work first is not as considerable as for WGP participants.

Conclusions and discussion

This study evaluated the long-term effects of an employer-based employment programme, the ‘Philips Employment Scheme’ [Philips Werkgelegenheidsplan (WGP) in Dutch], by comparing its long-term outcomes with a generic work-first support without such a skill-building component. Overall, we found positive employment programme participation effects on employment and competitive employment, except for the most dominant ethnic groups. Still, it does not go far enough to catch up with the labour force.

There is mixed evidence for Hypothesis 1 with respect to the positive long-term impacts for unemployed ethnic minorities from other non-western and western origins who participated in an employer-based employment programme. Results confirm Card et al.’s (2018) earlier findings showing substantial long-term effects on employment probabilities. The lesser impact of WGP participation on competitive employment mirrors the conclusion of Thijssen et al. (Reference Thijssen, Coenders and Lancee2021): employers still underestimate the average productivity of a minority group and are unwilling to pay formerly unemployed people a competitive salary even after vocational training because of prejudices, stereotypes, and remaining scarring effects (see Shi and Di Stasio, Reference Shi and Di Stasio2022).

The insignificant impact on long-term employment for the most dominant and established groups in the Netherlands – namely, Moroccans, Turks, Surinamese, and Dutch Antilleans – causes us to reject the hypothesis for this group. We would have expected a positive skill-investment impact on future labour market outcomes for these dominant ethnic groups compared with those subjected to work first. Yet, this effect did not appear in our analyses. Usually, social investment programmes like the WGP have positive long-term results on sustainable employment precisely because of the substantial skill investment not available in work-first support. While for some reason, this rationalisation may not apply to these groups of ethnic minorities.

There may be several explanations for these discrepant findings. Moroccan, Surinamese, Dutch Antillean, and Turkish minorities are often perceived more negatively in the Netherlands concerning their labour market attachment (Ramos et al., Reference Ramos, Thijssen and Coenders2019). In line with Liechti et al. (Reference Liechti, Fossati, Bonoli and Auer2017), employers assess ethnic minorities from the most dominant group as less remote from the labour market than those from non-western and western origins. The dominant groups may have better access to the Dutch education system than other newcomers, 72.45 per cent of the participants of Moroccan, Turkish, Surinamese or Dutch Antillean origin are the first generation of immigrants (see Table S.1.1). However, this information might be unknown to employers and still prejudice towards this group (see Zwaan, Reference Zwaan, Franzke and Ruano de la Fuente2021). Furthermore, earlier research shows much variation in the usage of unemployment and social assistance benefits (i.e. labour market histories) between ethnic minority groups and gender and age differences within these groups (Ministry of Social Affairs and Employment, 2018). Unfortunately, the group of participants was too heterogenous to draw solid conclusions about this mixed evidence on labour market interventions.

Another notable result is the similarity in long-term impact for other non-western and western participants of the WGP. The reasons for this cannot be empirically tested, but the results can somewhat be rationalised theoretically. Western immigrants’ qualifications are likely to be easier recognised by employers, reflected in our results by the slightly higher but more stable employment levels of the control group than non-westerners. Many immigrants from non-western countries, as, for instance, countries in the Middle East, may be highly educated but suffer from their qualifications being unrecognised in the Dutch education system, limiting their employment probabilities (Ministry of Social Affairs and Employment, 2018).

Moreover, both groups came to the Netherlands for different reasons (e.g. for seasonal work or as refugees), which somewhat determines the period of residence and the likelihood of having a work permit. Westerners – particularly people from countries of the European Union, e.g. Central and Eastern Europe included in the analyses – may have easier access to the Netherlands to perform seasonal work (van den Broek, Reference van den Broek2021). In contrast, non-western immigrants are often refugees from war zones (e.g. Arab and Sub-Saharan countries). They are likely to stay in the Netherlands for a more extended period, perhaps forever, but are not allowed to work in the Netherlands on short notice and suffer from human capital depreciation. This other non-western group experiences legal and practical barriers, while westerners from European member states could perform labour abroad more effortlessly (de Lange et al., Reference de Lange, Berntsen, Hanoeman and Haidar2021).

There is support for Hypothesis 2, which postulates the improved wage-match ratio that follows each intervention accountable for the long-term impact on employment and competitive employment. Results indicated – shown by the reductions on the main effect of the post-intervention dummy variables – that the WGP is more likely to evoke this change in wage match than work first does on short notice while respecting interventions’ different time horizons strategy. The predicted marginal effects show that the work first-entitled control group follows a slight sinusoidal path over the post-intervention years, indicating a vicious circle of insecure jobs and unemployment. As such, parallels can be drawn with the findings of Card et al. (Reference Card, Kluve and Weber2018) and Mattijssen and Pavlopoulos (Reference Mattijssen and Pavlopoulos2019), showing that the impact of work first may be more stable over time, but long-term unemployed people’s chances to advance in their careers remain dim.

Our study does not come without limitations. As earlier noted, most are due to the register data lacking time-(in)variant information such as language deficits, personality traits, and job-search efforts. Such data would have given us no insights into the underlying working mechanisms beyond skills investment. For instance, the daily routine at work may positively affect participants’ intrinsic motivation for job search compared with the pushing and distrustful work-first approach (Muffels, Reference Muffels, Laenen, Meuleman, Otto, Roosma and van Lancker2021). Against this backdrop, the two interventions remain a black box, as we could not explain the WGP’s and work first’s heterogeneous effects among the different ethnic groups.

The experiences of individuals with varying backgrounds during and after employment programmes compared with those entitled to work first are highly relevant for future research, untangling what works for whom and, most importantly, why it works for them. Although we could not test the impact of changing social capital on outcomes with the microdata, the professional network expansion for WGP participants may not be underestimated. Typically, the informal social networks of minorities within their ethnic group are popular job-finding vehicles but not always the most valuable ones as far as job quality is concerned (Patacchini and Zenou, Reference Patacchini and Zenou2012; van Tubergen, Reference van Tubergen2015; Kracke and Klug, Reference Kracke and Klug2021). These newly-acquired contacts may provide participants with valuable job information about available positions and potential referrals to recognise individuals’ skills (Leschke and Weiss, Reference Leschke and Weiss2020). WGP participants become part of the labour force and establish (interethnic) bonds with managers and colleagues on the shop floor. Yet, there may be variation between first and second-generation minorities.

Our findings can, to some extent, be generalised to other contexts. In particular, in dualised labour markets with a strong emphasis on vocational skills, a long-term-oriented programme with the strategic objective of establishing a better short-term wage match may tackle ethnic minority disadvantages better. In contrast, a short-term-oriented strategy without setting many job-quality requirements and assessing and solving initial unemployment problems may lead to poorer career development and, thus, more social cash transfers to be paid by society in the long run. The creation of a more level playing field for a heterogeneous group such as people with a minority background calls for more workplace-based investments in vocational skills, perhaps at different starting levels in educational attainment, further training, and social participation (de Graaf and van Zenderen, Reference de Graaf and van Zenderen2009; European Commission, 2017; Benda et al., Reference Benda, Koster and van der Veen2019).

Moreover, the observation period of this study includes two substantial recession periods (i.e. 2001-2004 and 2008-2009). Earlier research revealed that the WGP and similar initiatives perform better in times of economic crisis (Gerards et al., Reference Gerards, Muysken and Welters2014; Card et al., Reference Card, Kluve and Weber2018). The involvement of the business sector in the policymaking process is underdeveloped. Yet, paradoxically, their engagement is usually limited due to a lack of labour demand during these downturns (Bredgaard, Reference Bredgaard2018; van Berkel, Reference van Berkel2021). The labour market mobility of migrant workers can above all be improved by trade unions targeting those industries with an overrepresentation of these workers (see Confurius et al., Reference Confurius, van de Werfhorst, Dagevos and Gowricharn2022). In addition, Philips operates this programme mainly in the so-called Brainport region (City of Eindhoven), with technology-oriented businesses, such as ASML, Intel, and IBM, confronted with future skill shortages. The influence of such demand-side factors cannot be ignored, independent of any skill investment. Local opportunities provided by larger businesses and SME collectives that know well what skills the regional labour asks for may nonetheless be a possibility of a more sustainable solution to their very own problem of the growing number of hard-to-fill skill-shortage vacancies (Hyggen and Vedeler, Reference Hyggen and Vedeler2021).

Lastly, employers may shift their focus on people’s skills and their potential to learn the desired skills rather than on educational attainments (see Dekker et al., Reference Dekker, van den Bossche, Bongers and van Genabeek2021). More skill-based approaches may enable opportunities for people excluded from the labour market, as, for instance, people with a migration background, because of mistaken beliefs of (unrecognised) qualifications and proposed labour market (un)productivity.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474746422000756.

Acknowledgements

The first author wants to express great thanks to Prof. Dr. Ruud Muffels whose methodological knowledge truly helped shape this article. Further thanks are due to Royal Philips, Frank Visser, who allowed us the opportunity to conduct this study on their participants. The authors would like to thank the three anonymous reviewers for their high-quality reviews, which truly improved the article. Thanks to TNO for making this article open access.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical approval

Data are retrieved from Statistics Netherlands Microdata Services (CBS Microdata in Dutch). Access to the microdata is granted to scientific researchers under specific and strict privacy-securing conditions (i.e. Dutch universities, institutes for scientific research, organisations for policy advice or policy analysis, and statistical authorities in other countries of the European Union). Please see https://www.cbs.nl/en-gb/our-services/customised-services-microdata/microdata-conducting-your-own-research for more information. The Philips board agreed to share the data with Statistics Netherlands. Philips was aware that the outcomes of the present study must be published, following the guidelines of Statistics Netherlands, and agreed in advance to conduct a study on their program, regardless of the outcomes.