Tachyarrhythmia was one of the most common complications in patients after the classic Fontan procedure. Reference Poh, Zannino and Weintraub1–Reference Weipert, Noebauer and Schreiber3 It predominantly occurred as a response to progressive atrial stretch and had a prognostic implication associated with increased morbidity and mortality. Since the introduction of the total cavopulmonary connection, the survival and complication rate have improved drastically. Reference d'Udekem, Iyengar and Cochrane4–Reference Ono, Kasnar-Samprec and Hager6 Due to this improvement in life expectancy and functional status in patients with total cavopulmonary connection, the long-term follow-up complications have gained more and more importance. Reference Pundi, Johnson and Dearani7–Reference Oster, Knight and Suthar9 Among these, tachyarrhythmia appears to be one of the main concerns, along with thromboembolism, protein-losing enteropathy, plastic bronchitis, and ventricular failure. Reference Okólska, Karkowski and Kuniewicz10–Reference Lasa, Glatz, Daga and Shah15 Commonly observed tachyarrhythmias are atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter with a previously described incidence of 9–60%, and ventricular tachyarrhythmia with a described incidence of 2–16%. Reference Okólska, Karkowski and Kuniewicz10–Reference Lasa, Glatz, Daga and Shah15 These rhythm disturbances could cause severe clinical problems not only affecting the long-term outcome but also requiring further therapy or interventions. Reference Moore, Anderson and Nisbet16,Reference Pujol, Hessling and Telishevska17 Time of follow-up, atriopulmonary anastomosis, older age at Fontan operation, pre-operative and early post-operative tachycardia, and moderate-to-severe atrioventricular valve regurgitation have been identified as risk factors for the appearance of atrial tachyarrhythmia. Reference Okólska, Karkowski and Kuniewicz10–Reference Lasa, Glatz, Daga and Shah15 There is vast literature investigating tachyarrhythmia in adult patients after the Fontan procedure. Reference Egbe, Connolly and Khan18–Reference Gandhi, Bromberg and Schuessler20 However, there is limited data on the incidence, type, and treatment of tachyarrhythmia and their impact on late outcomes in a contemporary cohort of total cavopulmonary connection. Reference Egbe, Miranda and Devara21–Reference Carins, Shi and Iyengar23

In this study, we therefore aimed to determine the incidence and type of tachyarrhythmia in a large cohort of patients who underwent total cavopulmonary connection at our institution. Additionally, we intended to investigate the effectiveness of the treatments and to determine their prognostic impact on late outcomes.

Methods

Ethical statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Technical University of Munich (approved number of 2022-303-S-KH on 27 June, 2022). Because of the retrospective nature of the study, the need for individual patient consent was waived.

Patients and data collection

A single-centre retrospective cohort study of 620 consecutive patients who underwent a total cavopulmonary connection from May 1994 to December 2021 was performed. Medical records included baseline morphology and demographics as well as perioperative data using electronic and paper chart reviews of each patient. The patients obtained outpatient follow-ups with paediatric cardiologists. The most current vital status and follow-up data including the onset of tachyarrhythmia and systemic ventricular systolic function were obtained from our institutional single-ventricle database, which is regularly tracked. The detail of the assessment of ventricular systolic function was described in our previous study. Reference Dahmen, Heinisch and Staehler24

Operative techniques

Total cavopulmonary connection is defined as total cavopulmonary anastomosis (superior vena cava (SVC) is directly connected to the right pulmonary artery, and inferior vena cava (IVC) is connected to the right pulmonary artery using a lateral tunnel or extra-cardiac conduit technique), and the right atrium was excluded from the Fontan pathway. In patients with situs inversus, SVC and IVC are connected to the left pulmonary artery. On the contrary, “classic” Fontan procedure included atriopulmonary anastomosis (Fontan–Kreutzer procedure) and atrioventricular anastomosis (Fontan–Björk procedure). In the Fontan–Kreutzer procedure, SVC flow and IVC flow drained into the right atrium and both SVC flow and IVC flow together go through to the pulmonary artery via the atrial appendage–main pulmonary artery anastomosis. In the Fontan–Björk procedure, the right atrial appendage was anastomosed to the infundibular portion of the right ventricle. In “classic” Fontan procedure, the right atrium was used for the Fontan pathway. The operative techniques for total cavopulmonary connection are described in previous reports. Reference Ono, Kasnar-Samprec and Hager6,Reference Schreiber, Hörer and Vogt25 Fenestration was not routinely performed and was only used for high-risk patients. Reference Ono, Kasnar-Samprec and Hager6

Diagnosis of tachyarrhythmia and corresponding therapies

Patients' rhythm were regularly checked in hospital and also in outpatient clinics during rest in supine position using a standard 12-lead electrocardiogram. Experienced analysts reviewed the record of patients undergoing 24-hour Holter recording during normal daily activity. Tachyarrhythmia was defined as a documented atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter including cavo-tricuspid and non-cavo-tricuspid-related intra-atrial reentry tachycardia, not further specified supraventricular tachycardia, or focal atrial tachycardia. Ventricular arrhythmias comprised sustained ventricular tachyarrhythmia and ventricular fibrillation. We identified the point of time at which an arrhythmia was first recognised. Frequency and type of treatment, as well as success rates, were analysed. Early arrhythmia was defined as tachyarrhythmia observed in hospital stay after total cavopulmonary connection, and late arrhythmia was defined as tachyarrhythmia observed after hospital discharge. Treatment was classified as pharmacologic treatment (class I – class IV), direct current cardioversion, or electrophysiology study with and without ablation. During electrophysiology study, acute success was defined as the termination of tachycardia. The primary end point was the onset of any tachyarrhythmia requiring treatment. To determine the prognostic impact of arrhythmia on long-term outcomes, we examined late end points of Fontan circulatory failure, defined as death, heart transplantation, Fontan takedown, protein-losing enteropathy, plastic bronchitis, or NYHA functional class III or IV at follow-up. Protein losing enteropathy was diagnosed as defined by Rychik and colleagues’ statement Reference Rychik, Atz and Celermajer26 from the American Heart Association, by symptoms of oedema without another identified cause and also by an elevated a-1 antitrypsin clearance in a 24-hour stool collection or an elevated a-1 antitrypsin level in a single stool sample paired with the presence of serum hypoalbuminemia. The diagnosis of plastic bronchitis was made by expectoration of casts, bronchoscopy, and histologic examination.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables are presented as absolute numbers and percentages. A chi-square test was used for categorical data. Continuous variables are expressed as medians with interquartile ranges. An independent sample t-test was used to compare normally distributed variables. The Mann–Whitney U-test was used for variables that were not normally distributed. Freedom from tachyarrhythmia and freedom from Fontan circulatory failure after the onset of tachyarrhythmia were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method, and differences between groups were determined using log-rank test. Risk factor analysis for the early onset of tachyarrhythmia was performed using linear regression model, and analysis for late onset of tachyarrhythmia was performed using Cox regression model. Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 28.0 for Windows (IBM, Ehningen, Germany) and R-statistical software (state package).

Results

Patient characteristics and perioperative data

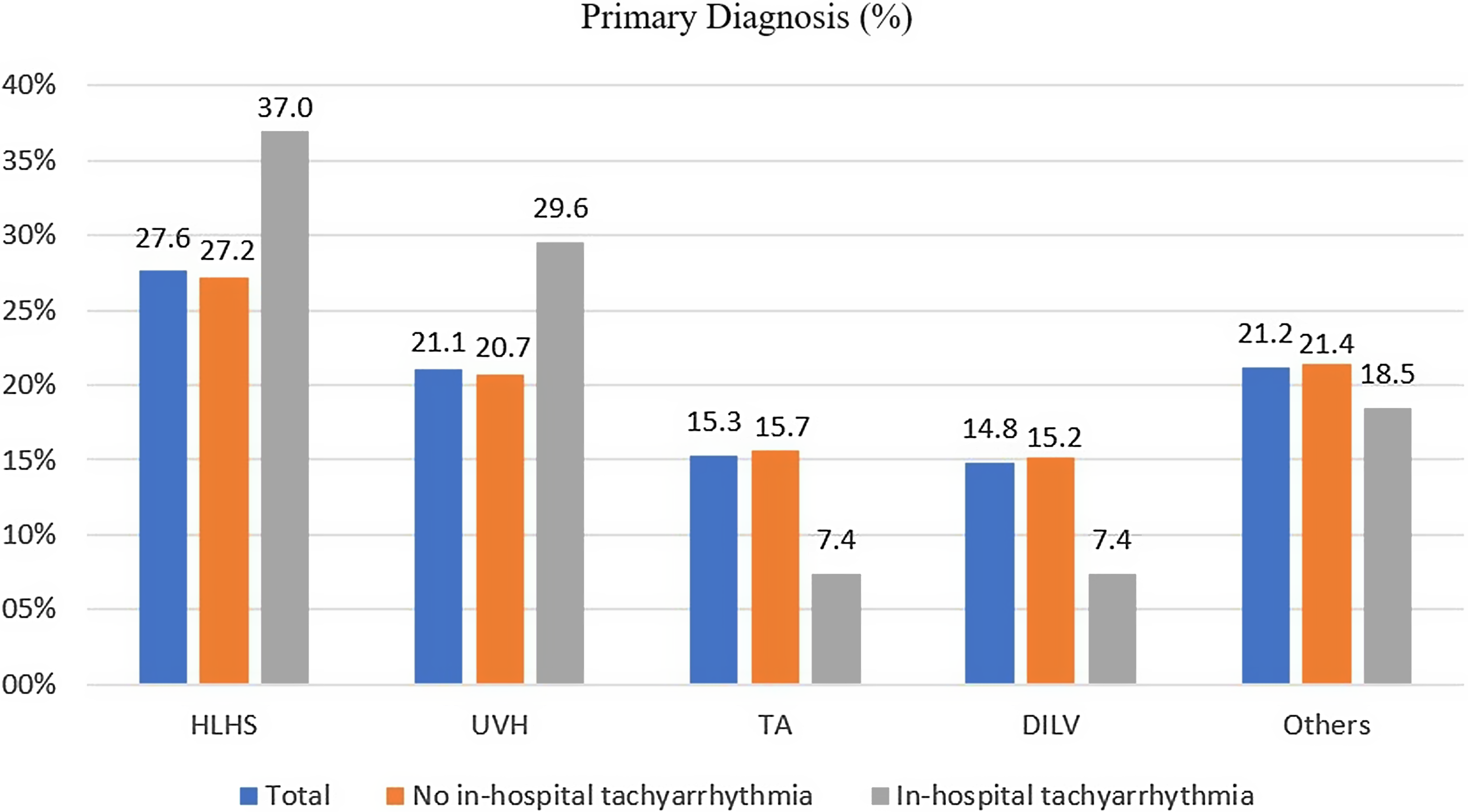

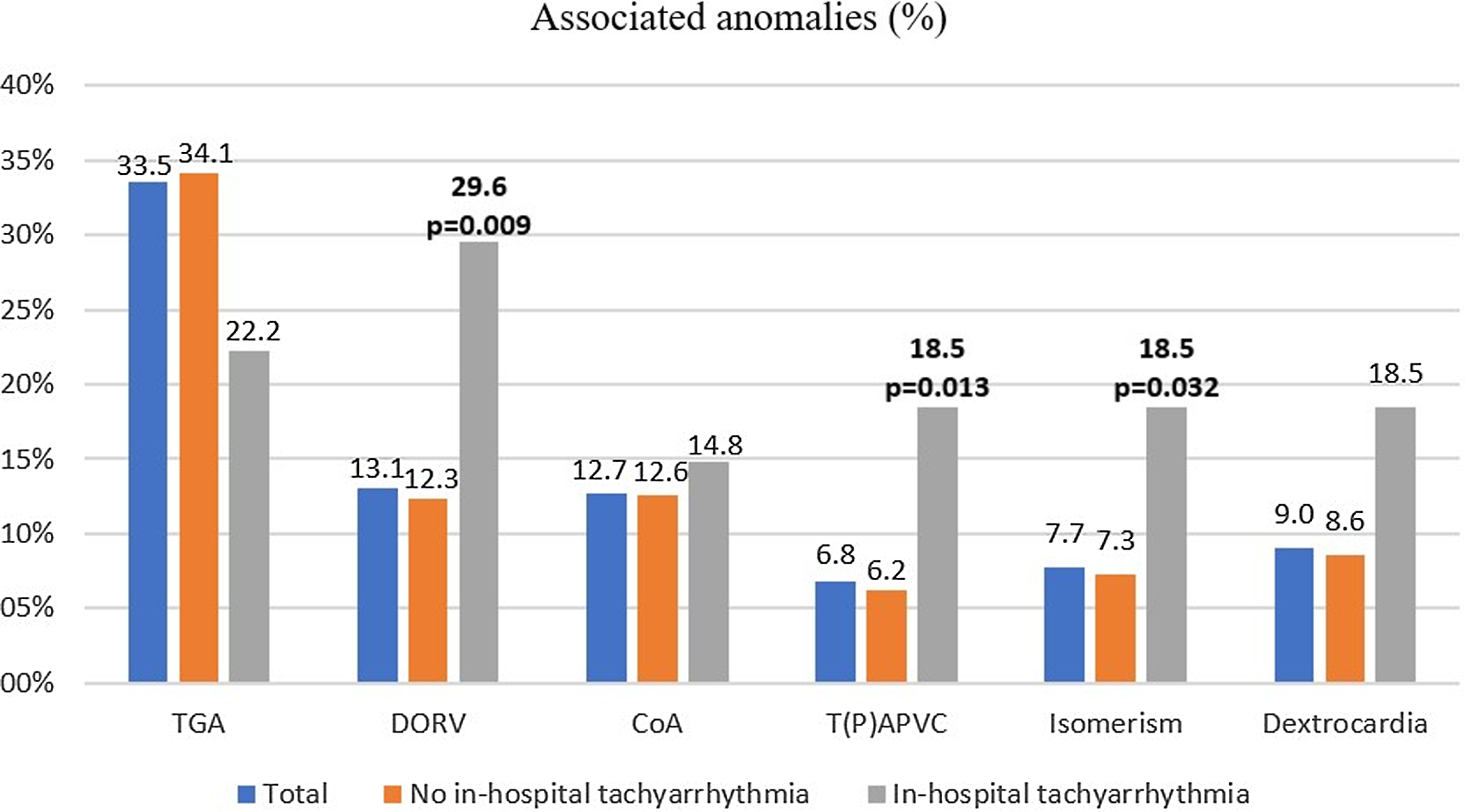

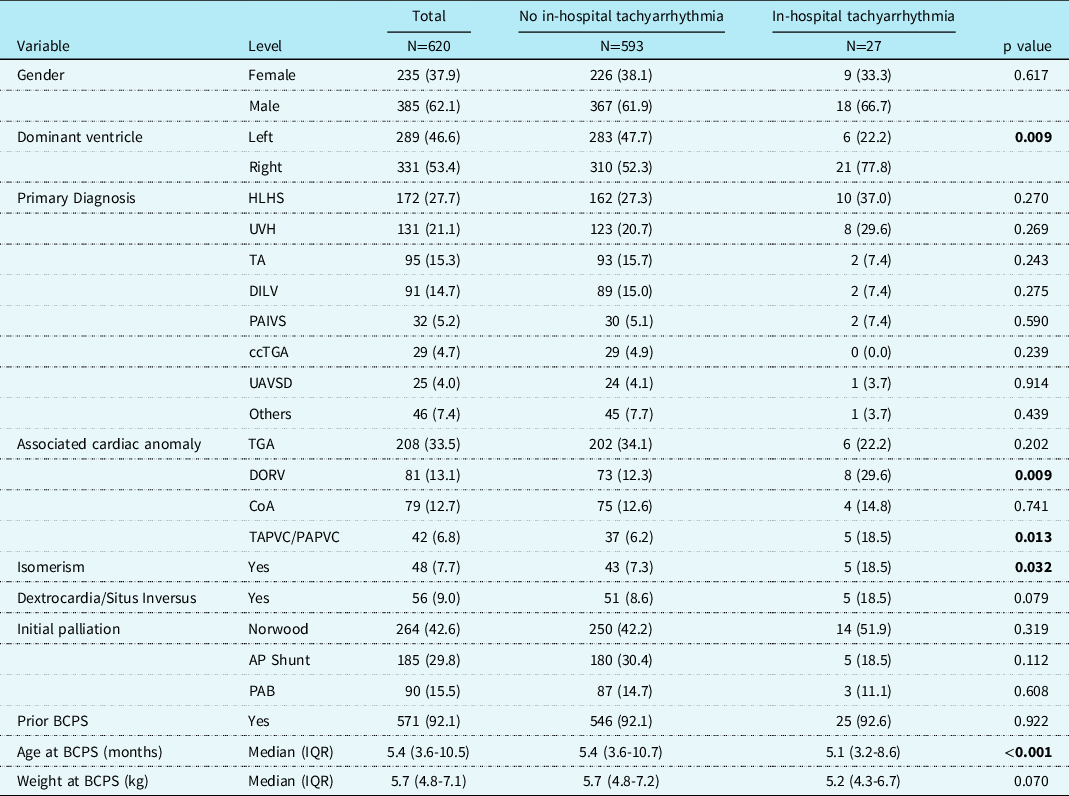

Tachyarrhythmia was observed in hospital following total cavopulmonary connection in 27 (4.3%) patients. The incidence of dominant right ventricle (77.8% versus 52.3%, p = 0.009), double-outlet right ventricle (29.6% versus 12.3%, p = 0.009), total anomalous pulmonary venous connection/partial anomalous pulmonary venous connection (18.5% versus 6.2%, p = 0.013), and isomerism (18.5% versus 7.3%, p = 0.032) were more frequently observed in patients with in-hospital tachyarrhythmia, compared to those without in-hospital tachyarrhythmia (Table 1, Fig. 1, and Fig. 2).

Figure 1. Bar chart comparing the primary diagnosis between patients with and without the onset of in-hospital tachyarrhythmia.

Figure 2. Bar chart showing the distribution of associated anomalies between patients with and without the onset of in-hospital tachyarrhythmia.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of the 620 patients who underwent TCPC.

BCPS = bidirectional cavopulmonary shunt; ccTGA = congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries; CoA= coarctation of the aorta; DILV = double-inlet left ventricle; DORV = double-outlet right ventricle; HLHS = hypoplastic left heart syndrome; PAB = pulmonary artery banding; PAIVS = pulmonary atresia with intact ventricular septum; TA = tricuspid atresia; TAPVC/PAPVC = total anomalous pulmonary vein connection/ partial anomalous pulmonary vein connection; TCPC, total cavopulmonary connection; TGA = transposition of the great arteries; UAVSD = unbalanced atrioventricular septal defect; UVH = univentricular heart.

Patient diagnosis of functional univentricular heart was classified according to the modified congenital Heart Surgery Nomenclature and Database Project classification.

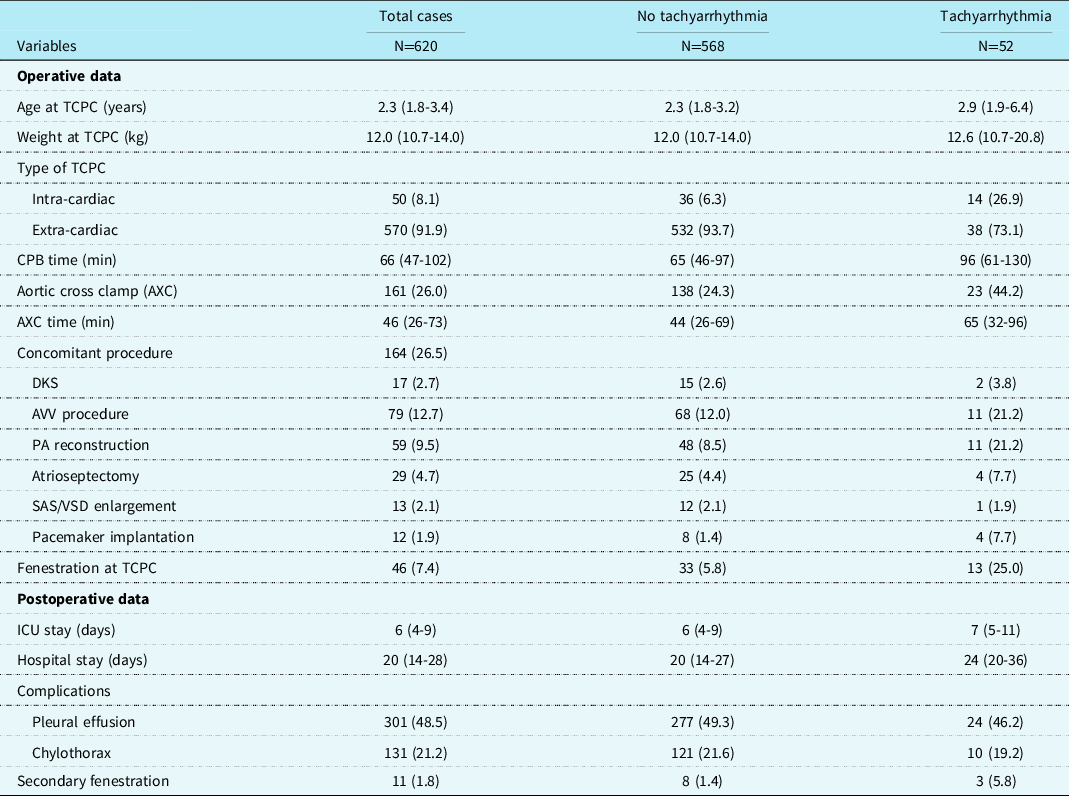

Median age and weight at total cavopulmonary connection were 2.3 years (interquartile ranges: 1.8–3.4) and 12.0 kg (10.7–14.0), respectively (Table 2). Lateral tunnel total cavopulmonary connection was performed in 50 patients and extra-cardiac total cavopulmonary connection in 570. Fenestration was placed in only 46 (7%) patients. There were eight in-hospital deaths.

Table 2. Perioperative variables.

AVV = atrioventricular valve; CPB = cardiopulmonary bypass; DKS = Norwood/Damus–Kay–Stansel; PA = pulmonary artery; SAS/VSD = subaortic stenosis/ventricular septal defect; TCPC = total cavopulmonary connection.

Follow-up and occurrence of tachyarrhythmia

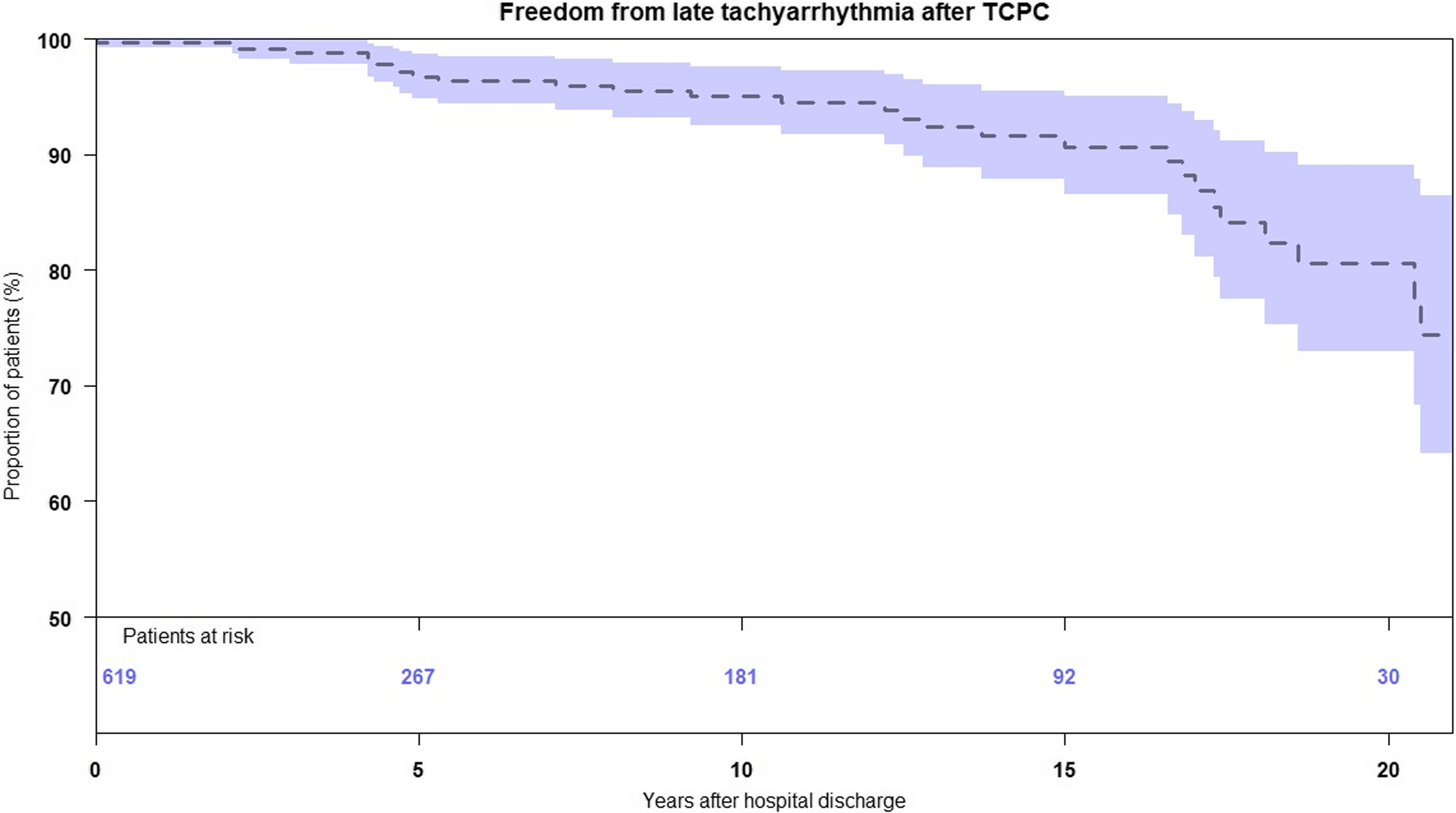

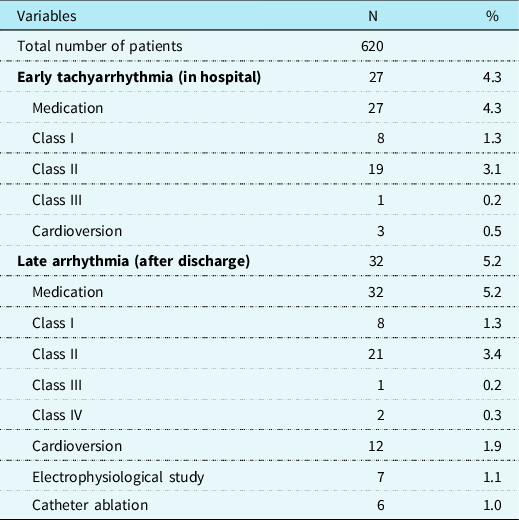

Among 612 early survivors, 10 patients were lost to follow-up after their hospital discharge. The median follow-up period was 5.9 (interquartile ranges: 1.2–13.1) years in the remaining 602 patients. There were 15 late deaths, 4 heart transplantations, and no Fontan takedown. Transplant-free survival at 5, 10, and 15 years was 96.8, 94.6, and 94.2%, respectively. During the study period, 52 (8.4%) patients presented with tachyarrhythmia (Table 3). Tachyarrhythmia was observed in hospital following total cavopulmonary connection in 27 (4.3%) patients and was diagnosed during follow-up periods in 32 (5.2%) patients with median interval of 11.0 (4.6–16.9) years. Freedom from the onset of tachyarrhythmia after hospital discharge was 96.8% (95% confidence interval: 94.8–98.7) at 5 years, 95.0% (95% confidence interval: 92.5–97.6) at 10 years, and 90.7% (95% confidence interval: 86.5–95.0) at 15 years, respectively (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Kaplan–Maier estimate of freedom from the onset of tachyarrhythmia after hospital discharge following TCPC. TCPC, total cavopulmonary connection.

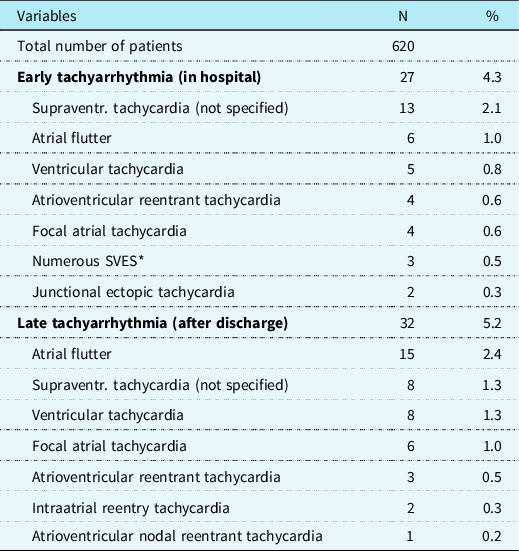

Table 3. Type of tachyarrhythmia.

SVES = supraventricular extrasystole.

Therapy for tachyarrhythmia

In 27 patients with early tachyarrhythmia, initial medication included class II in 19 patients, class I in 8 patients, and class III antiarrhythmics in 1 patient (Table 4). Three patients underwent direct current cardioversion. All patients were discharged with sinus rhythm, and late tachyarrhythmia was observed in seven patients with a median of 4.2 years after total cavopulmonary connection. At the last follow-up, 11 patients needed medication including class II in 8 patients, class I in 2, and class III in 2.

Table 4. Therapy after the onset of tachyarrhythmia.

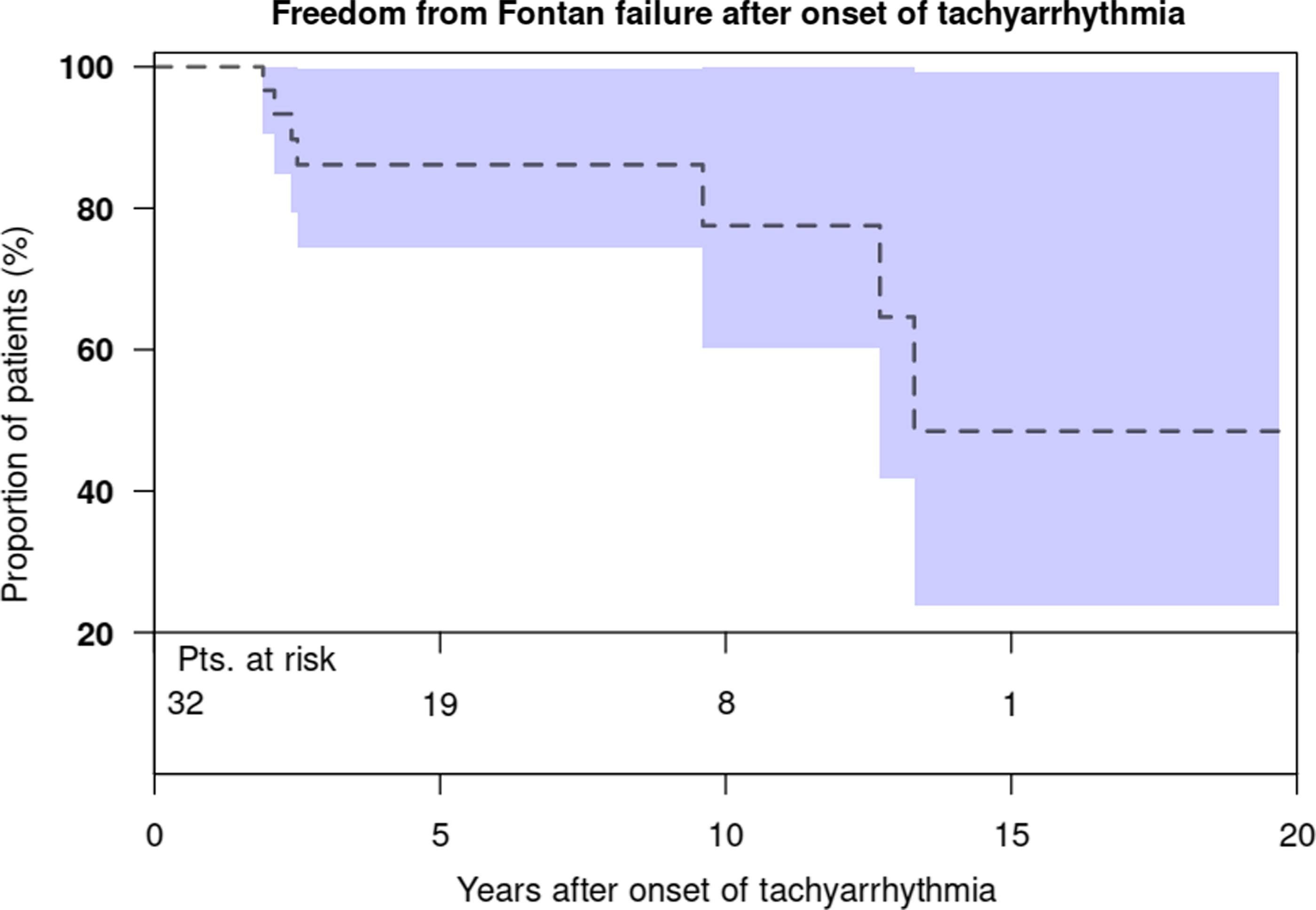

In 32 patients with late arrhythmia, medical therapy included class II in 21 patients, class I in 8, class IV in 2, and class III in 1. A single episode of tachyarrhythmia was observed in 16 patients (50.0%), with no recurrence after a median follow-up of 5.2 (2.3–8.5) years. The remaining 16 patients (50.0%) had multiple episodes of tachyarrhythmia, and 3 patients (9.4%) experienced more than 3 symptomatic tachyarrhythmic episodes. Those who experienced a single versus multiple (>1) episodes of tachyarrhythmia showed no significant differences in the freedom from Fontan circulatory failure (single: 88% versus multiple: 84%, P = .17) at 5 years (Supplementary Figure S1). Direct current cardioversion was required in 12 (37.5%) patients, and a repeat direct current cardioversion was required in 4 patients (12.5%). Seven patients (21.9%) received an electrophysiology study at a median of 439 days after the first onset of tachyarrhythmia, and six of them (18.8%) underwent consequent catheter ablation. The results after electrophysiology study are shown in Supplementary Table S1. Acute success was obtained in five out of six patients, but three patients needed direct current cardioversion after ablation therapy. During follow-up after the onset of tachyarrhythmia, three patients died, two patients developed protein-losing enteropathy, one patient developed plastic bronchitis, and six patients developed NYHA class III or IV symptoms. No patient with tachyarrhythmia underwent heart transplantation. In total, seven patients reached the composite end point of Fontan circulatory failure. Freedom from Fontan circulatory failure after the onset of a tachyarrhythmia were 86.2, 77.5, and 48.5% at 5, 10, and 15 years, respectively (Fig. 4). At last follow-up, 19 patients (59.4%) needed anti-arrhythmic medication, including class II medications in 16 patients, followed by class I in 2, and class III in 1.

Figure 4. Kaplan–Maier estimate of freedom from Fontan circulatory failure after the onset of late tachyarrhythmia.

Among patients with tachyarrhythmia, reduced ventricular systolic function was observed in eight patients (8/32, 25%) before the onset of tachyarrhythmia in four patients and after the onset of tachyarrhythmia in four patients. After the onset of tachyarrhythmia, freedom from the onset of reduced ventricular systolic function at 5 years was 85%.

Risk factors for the onset of tachyarrhythmia

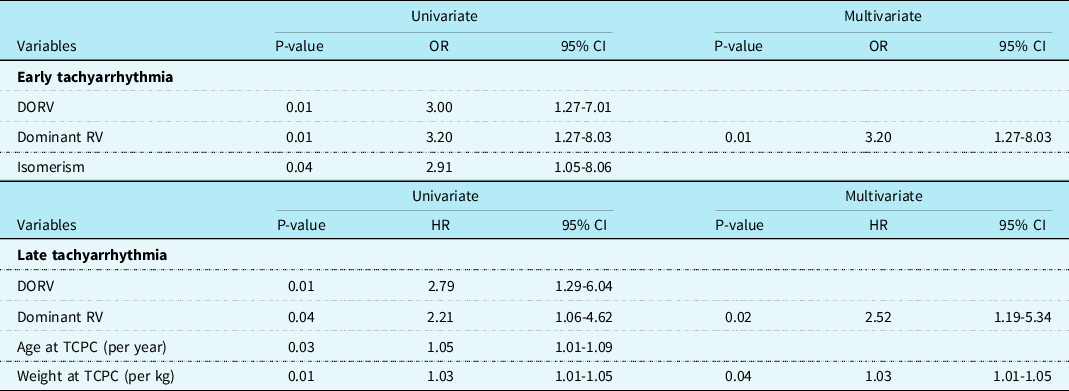

As for the early onset of tachyarrhythmia during hospital stay, double-outlet right ventricle (p = 0.01, odds ratio: 3.00), dominant right ventricle (p = 0.01, odds ratio: 3.20), and isomerism (p = 0.04, odds ratio: 3.00) were risk factors using univariate analysis, and dominant right ventricle (p = 0.01, odds ratio: 3.20) was an independent risk factor using multivariate analysis (Table 5). As for the late onset of tachyarrhythmia, double-outlet right ventricle (p = 0.01, hazard ratio: 2.79), dominant right ventricle (p = 0.04, hazard ratio: 2.21), older age at total cavopulmonary connection (p = 0.03, hazard ratio per year: 1.05), and heavier weight at total cavopulmonary connection (p = 0.01, hazard ratio per kg: 1.03) were risk factors using univariate analysis, and dominant right ventricle (p = 0.02, hazard ratio: 2.52) and heavier weight at total cavopulmonary connection (p = 0.04, hazard ratio per kg: 1.03) were independent risk factors using multivariate analysis. The results of other variables are shown in Supplementary Table S2. As for the type of total cavopulmonary connection, patients with extra-cardiac total cavopulmonary connection had a tendency of better freedom from tachyarrhythmia than those with lateral tunnel total cavopulmonary connection, but p-value did not reach a significant difference (p = 0.075) in the late onset of tachyarrhythmia (Supplementary Figure S2). When we analysed the episode of an early tachyarrhythmia as a risk for late tachyarrhythmia, it was identified as a significant risk for late tachyarrhythmia (p < 0.001, hazard ratio: 15.641, 95% confidence interval = 6.355–38.492).

Table 5. Risk factors for the onset of tachyarrhythmia.

CI = confidence interval; DORV = double-outlet right ventricle; HR = hazard ratio; RV = right ventricle; OR = odds ratio; TCPC = total cavopulmonary connection.

Comment

Among 620 patients who underwent total cavopulmonary connection, freedom from late tachyarrhythmia after hospital discharge was 91% at 15 years. Dominant right ventricle and higher weight at total cavopulmonary connection were risks for the late onset of tachyarrhythmia. Freedom from Fontan circulatory failure after the first onset of arrhythmia was 86.2, 77.5, and 48.5% at 5, 10, and 15 years, respectively.

Incidence of tachyarrhythmia

Compared to patients after the classic Fontan procedure, the incidence of tachyarrhythmia after total cavopulmonary connection has been reported lower, ranging from 4 to 40% Reference d'Udekem, Iyengar and Cochrane4,Reference Nakano, Kado and Tatewaki5,Reference Egbe, Connolly, Niaz and McLeod12,Reference Lasa, Glatz, Daga and Shah15,Reference Quinton, Nightingale and Hudsmith22,Reference Carins, Shi and Iyengar23,Reference Schmiegelow, Idorn and Gislason27 at 10–15 years. Our results of 9% at 15 years were consistent with previous reports. In general, there is no progressive atrial stretch in patients after total cavopulmonary connection, and a lower incidence of tachyarrhythmia is a great advantage of total cavopulmonary connection. In this study, we found the tendency that extra-cardiac total cavopulmonary connection was better in the freedom from tachyarrhythmia than lateral tunnel total cavopulmonary connection. However, there was no significant difference in the incidence of tachyarrhythmia in lateral tunnel total cavopulmonary connection and extra-cardiac total cavopulmonary connection. This issue is still controversial. Several studies demonstrated better freedom from tachyarrhythmia in extra-cardiac total cavopulmonary connection than lateral tunnel total cavopulmonary connection, Reference Azakie, McCrindle and Van Arsdell28–Reference Robbers-Visser, Miedema and Nijveld30 and other studies showed no significant difference in the incidence of arrhythmia between lateral tunnel total cavopulmonary connection and extra-cardiac total cavopulmonary connection Reference Lasa, Glatz and Daga31–Reference Balaji, Daga and Bradley33 or better outcome after lateral tunnel total cavopulmonary connection in regard to tachyarrhythmia. Reference Brown, Ruzmetov and Deschner34 Therefore, we cannot conclude that extra-cardiac total cavopulmonary connection is definitively better than lateral tunnel total cavopulmonary connection in regard to late tachyarrhythmia.

In our study, we found atrial tachyarrhythmia in almost 75% and ventricular tachyarrhythmia in 25% of the patients, and atrial flutter was the most frequent atrial tachyarrhythmia. Other studies demonstrated that the most frequent tachyarrhythmia to be cavo-tricuspid and non-cavo-tricuspid-related intra-atrial reentry tachycardia. Reference Okólska, Karkowski and Kuniewicz10–Reference Lasa, Glatz, Daga and Shah15 These can be triggered by scar tissue in the atria, chronic atrial pressure, or volume overload. Reference Stephenson, Lu and Berul13,Reference Fishberger, Wernovsky and Gentles14 Moreover, other factors associated with older age, such as higher body mass index, arterial hypertension, dyslipidemia, cigarette smoking, and coronary artery disease, might favour the presence of atrial flutter. Reference Egbe, Connolly, Niaz and McLeod12,Reference Lewis, Whang and Biviano35

Results after therapy

In this study, patients with early tachyarrhythmia showed a good response to medical therapy and direct current cardioversion, and all patients were discharged with sinus rhythm. Recurrent tachyarrhythmia was observed in only seven patients. Among 32 patients with late tachyarrhythmia, 21 patients needed direct current cardioversion and 7 patients, in whom pharmacologic treatment had been ineffective, received an electrophysiology study and 6 of them underwent subsequent ablation. Immediate success was achieved in all but one patient. The results were consistent with the results of other studies. Reference Okólska, Karkowski and Kuniewicz10–Reference Lasa, Glatz, Daga and Shah15 Acute procedural success in ablation therapy has been reported as a predictor of recurrence-free survival. In our study, recurrence of tachyarrhythmia after electrophysiology study was seen only in one patient, and all of the seven patients were alive.

There is concern that the onset of a late tachyarrhythmia is the first sign of deterioration or failure of the Fontan circulation. Patients who develop late atrial tachyarrhythmia are more prone to Fontan circulatory failure, ventricular systolic dysfunction, and hospitalisations. In this study, 7 of 32 patients who developed late tachyarrhythmia reached the composite end point of Fontan circulatory failure, and freedom from Fontan circulatory failure after the onset of arrhythmia was 78 % at 10 years and 49% at 15 years. These results were consistent with the report by Carins et al. Reference Carins, Shi and Iyengar23 Survival after the onset of arrhythmia was surprisingly good: there were only 3 deaths among 32 patients, that is, more than 90% survival at 10 years after the onset of a tachyarrhythmia. Previous reports demonstrated that the onset of arrhythmia would be associated with a rapid decline in survival. Reference Poh, Zannino and Weintraub1–Reference Weipert, Noebauer and Schreiber3

Risks for late-onset tachyarrhythmia and future prospective

We found dominant right ventricle and heavier weight at total cavopulmonary connection to be predictors of developing late tachyarrhythmia. These findings are consistent with those previously reported by our group. In other studies, atriopulmonary Fontan, atrial isomerism, and dextrocardia were also reported as risk factors of developing tachyarrhythmia. In this study, isomerism was identified as a risk factor for early tachyarrhythmia, but not for late tachyarrhythmia. Of note, patients twith the extra-cardiac conduit total cavopulmonary connection were not less likely to experience a tachyarrhythmia compared with those with lateral tunnel total cavopulmonary connection. In this study, the median age and weight at total cavopulmonary connection were 2.3 years and 12 kg, respectively, and older age and heavier weight at total cavopulmonary connection were risks for late tachyarrhythmia. Our current strategy is to perform total cavopulmonary connection completion from 18 months of age and from 10 kg weight as soon as patients reach these criteria. These results support our rationale for this strategy. We are convinced that early farewell to cyanosis and preservation of the systemic ventricular systolic function is most important to prevent late Fontan complications including tachyarrhythmia.

It is of note that double-outlet right ventricle was identified as a risk for both early and late tachyarrhythmia. We think this is a new finding. There are case reports describing tachyarrythmia late after total cavopulmonary connection in patients with double-outlet right ventricle. Reference Ferrari, Shehu and Stern36,Reference Mizuno, Nishii and Morita37 However, there was no study that demonstrated that double-outlet right ventricle is a risk for tachyarrhythmia after the Fontan procedure. Wilkinson et al. demonstrated in their 22 specimens study that the conduction system originated from a normally placed atrioventricular node in 4 out of 6 cases and was related to the trabecular septum in 5. The penetrating bundle usually descended onto the crest of the septum at the "crux" of the heart and bifurcated astride it. In two cases with an absent atrioventricular connection, the penetrating bundle originated from an abnormally placed node and in one of these specimens a sling of conducting tissue was identified with dual pathways. Reference Wilkinson, Keeton and Dickinson38 These varieties of the conduction system might cause the higher incidence of tachyarrhythmia after total cavopulmonary connection. Further studies are mandatory to clarify the exact abnormalities of conductive tissue and the incidence of tachyarrhythmia in patients with double-outlet right ventricle.

Limitation

This study was limited by its retrospective and single-centre design. Changes in surgical and medical management have occurred with time that may not be covered by our analyses, and that may affect the long-term results. Changes in surgical management include the introduction of extra-cardiac total cavopulmonary connection since 1999 and the no fenestration policy since 2001. A tangible change regarding post-operative management was the adoption of an early extubation strategy even for unstable patients. The limited number of outcome events might limit the reliability of the Cox regression results in some cases (end points). In addition, the small number of outcomes limits the statistical power of analysis. Data were not available at consistent follow-up periods for every patient. Patients referred from other institutions might have a different history and quality of their remote medical and surgical management, and these factors could affect long-term outcomes.

Conclusions

Freedom from late tachyarrhythmia at 15 years was 91% following total cavopulmonary connection. Electrophysiology study and subsequent ablation demonstrated high rate of success in patients. Patients with dominant right ventricle and heavier weight at total cavopulmonary connection were at increased risk for late tachyarrhythmia. Freedom from Fontan circulatory failure after the first onset of an arrhythmia was 77.5% at 10 years, and close surveillance of clinical condition is required for this cohort.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1047951123003141

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Mrs. Martina Strbad for her excellent data management and secretarial support at the study center for Department of Congenital and Pedoatric Heart Surgery at the German Heart Center Munich.

Author contribution

Cornelius Bohn and Thibault Schaeffer contributed equally.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

None.