“In retrospect, it appeared like a large chess game of moves and counter moves.” So read a 101st Airborne Division “lessons learned” report from fighting near the A Shau Valley, a strategic corridor linking South Vietnam to the Laotian border and Hồ Chí Minh Trail beyond. It seems unlikely, however, that the American soldiers defending Firebase Ripcord in the summer of 1970 felt they were playing chess. Charged with protecting a small hilltop at valley’s edge, accessible only by helicopter, they endured People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN) ambushes, mortar barrages, and artillery fire for nearly a month. When the siege of Ripcord ended, seventy-five Americans lay dead. Games normally do not come at so high a cost.Footnote 1

To senior US military commanders, the fighting near A Shau surely made operational sense. The valley had long been a conduit for Hanoi to send critical manpower replacements and supplies into South Vietnam. The 101st Airborne had seen heavy fighting there in 1969, most infamously at “Hamburger Hill” in May. One year later, troubled US commanders again were reading intelligence reports suggesting enemy forces were on the move. They feared the “Warehouse Area,” the valley’s nickname, might serve as a launching pad for strikes into South Vietnam’s coastal lowlands and population centers. With these concerns in mind, Operation Texas Star took shape. The 101st would conduct “protective reaction” missions in the A Shau region, with newly established firebases providing artillery cover to US and South Vietnamese infantry troops on the valley floor below. Ripcord was the pivotal base along this protective chain.Footnote 2

Almost immediately, though, the Americans met resistance while establishing their firebases. Commanders called in airstrikes in late March to “soften up the area,” and by early April, Ripcord was turning into a heavily bunkered stronghold. Yet neither airstrikes nor patrols drudging through the valley’s jungles made any headway in dislodging enemy forces from the mountaintops surrounding the firebase. By July, Ripcord was under siege. As North Vietnamese mortar and artillery shells descended on American GIs, US commanders ultimately decided to postpone a planned offensive into the valley and evacuate the area. For the second time in two years, American forces had fought hard in A Shau, only to cede bloodied ground back to the North Vietnamese. As B-52 bombers flew in to obliterate what was left of Ripcord after its abandonment, one US officer laconically stated that “we didn’t want to leave anything behind that the enemy could use.”Footnote 3

With the Nixon administration already withdrawing from a long and costly war, the fighting around Ripcord would rank among the last major ground combat operations conducted by the US armed forces in South Vietnam. Yet larger questions remained as the Americans departed the A Shau valley. Were operations there successful? Who had “won” given that so much American blood had been spilled for a plot of land almost immediately abandoned? Officers would argue then and later that the “occupation of Ripcord provided a barrier to possible [North Vietnamese Army, NVA] plans to attack the coastal lowlands” and “absorbed considerable NVA strength and military stores.” Others were far less charitable in their assessments. Writers in Newsweek described the Ripcord fighting as a “painful” operation and wondered aloud why “American soldiers had been asked to set up a fire base in the midst of an enemy stronghold to begin with.” Indeed, some soldiers felt they had been left “hanging” as “bait.” That the US command in Saigon discouraged reporters from visiting Ripcord did little to foster a sense of optimism about what lay ahead.Footnote 4

The A Shau valley fighting in 1970 serves well as a microcosm for evaluating the enduring problems Americans faced as they withdrew from their war in Vietnam. At all levels, from tactical to strategic to political, uncertainty persisted over how the conflict would end. Military commanders had to consider not only troop withdrawal rates, but the level of enemy activity and the prognosis of Vietnamization, the phrase used for gradually handing the war over to their South Vietnamese allies. Diplomats had to balance peace negotiations with the Nixon administration’s larger aims of rapprochement with China and the Soviet Union. All the while, the White House sought to end its war on terms that preserved US credibility around the globe.Footnote 5 In all these areas, the terms “victory” and “defeat” remained imprecise and constantly in flux. Indeed, a setback in one area might hold lasting consequences elsewhere. No wonder the US Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV) worried that “adverse publicity” from Ripcord “might well have jeopardized the entire Vietnamization program.”Footnote 6

These uncertainties matter because they influenced the timing of and ways in which US forces withdrew from a conflict that would not be terminated once Americans departed South Vietnam. Near war’s end, evaluating the progress and effectiveness of US strategy proved as bewildering as it had been nearly a decade earlier. Every new initiative seemed only to produce a frustratingly new state of equilibrium. Any successes in pacification seemed only to increase the Saigon government’s dependence on American aid. Any accomplishments in Vietnamization seemed only to hasten calls for US troop withdrawals, leaving an exasperated Henry Kissinger in Paris to argue he was losing leverage over his North Vietnamese negotiating partners. And, ultimately, the flawed strategic process of exiting Vietnam’s war set the foundation for future debates over whether the American armed forces could claim victory, be forced to acknowledge defeat, or concede they had achieved, at most, a costly stalemate against a determined enemy.Footnote 7

“One War,” but a Winning One?

By mid-1968, American ground combat forces had been operating in South Vietnam for three full years. Despite massive efforts – US troop strength had reached 485,600 by the end of 1967 – the best that the Americans, the South Vietnamese, and their allies could achieve against their communist foes was a bloody stalemate. It was not for lack of trying. General William C. Westmoreland, MACV’s commander, had developed a comprehensive political–military strategy that sought to parry enemy military offensives, support Saigon’s pacification efforts, train South Vietnamese defense forces, and build a logistical infrastructure to sustain a major ground and air war. Still, neither side could break the deadly impasse. When Hanoi launched its Tet Offensive in early 1968, seeking a decisive military victory and popular uprising in the South, the result was only a continued stalemate. True, the Southern communist infrastructure had been nearly destroyed, but the devastation to the countryside and displacement of some 600,000 South Vietnamese civilians surely offset any credits to the allied ledger.Footnote 8

With the transition to a new MACV chief in the summer of 1968 came hopes of a fresh strategic approach yielding improved results. Westmoreland’s West Point classmate, Creighton Abrams, had amassed an impressive resumé, from his service with Patton in World War II to becoming MACV’s deputy commander in 1967. One year later, he took over a war that appeared to many Americans no longer worth fighting. Yet expectations rose, if only briefly. As one fellow officer recalled, “Abe” possessed that “rare quality, common sense, the knack of going straight to the heart of the problem, and insisting on a simple and workable solution.” But Abrams also bristled under the political restrictions placed upon him after the bloody Tet battles. Secretary of Defense Clark Clifford, for instance, correctly gauged the political winds and knew military commanders in Vietnam would have to keep casualties down if they were to maintain popular support back home. The loss of over 14,500 American lives in South Vietnam during 1968, though, suggested Abrams might not have the ability to singlehandedly manipulate events as his enthusiasts predicted.Footnote 9

The new MACV commander certainly spoke in terms that appeared pioneering. He espoused a “one war” approach, in which the allies would respond to an enemy working along numerous “levels” or “systems.” Abrams could not ignore the military aspect of the war. But he also had to bring the South Vietnamese armed forces to an “acceptable level of proficiency,” all while supporting pacification and countering communist “attempts to subvert people in remote areas.” As the general instructed his subordinate commanders, “All types of operations are to proceed simultaneously, aggressively, persistently, and intelligently … never letting the momentum subside.”Footnote 10 Such language fit Abe’s forceful personality. Yet just below the surface, the “one war” approach bore strong resemblance to Westmoreland’s own “balanced” or “two-fisted strategy.” Both commanders realized they were fighting a complex war, the outcome of which depended upon political matters as much as military ones. In truth, few truly innovative strategic concepts emerged during Abrams’ tenure as MACV commander.Footnote 11

Champions of the Massachusetts native, though, long have advocated that Abrams turned the war around in short order. With hagiographic grandeur, historian Lewis Sorley, for example, has argued the general changed tactics “within fifteen minutes” of taking command, fought a “better war,” and ultimately achieved victory in the spring of 1970. To Sorley, MACV abandoned the misguided “search-and-destroy” concept – and the grisly body-count metrics – to instead focus on “clear-and-hold” operations aimed at pacifying the countryside.Footnote 12 But adulation makes for bad history. In reality, Abrams, at best, altered US military strategy along the margins. Search-and-destroy operations remained a vital component of MACV’s approach, and new scholarship demonstrates clearly that Abrams’ attitude toward pacification was “just as reliant on heavy firepower and main-force operations as it was under Westmoreland.” In short, there was “no fundamental change in strategy.” The new MACV chief may have thought of the war as a single yet multifaceted conflict, but the “one war” term did not herald a major shift in the war’s prosecution.Footnote 13

Nor did MACV operations prove any more successful than those directed by Westmoreland. Abrams surely emphasized pacification efforts inside South Vietnam, taking advantage of casualties suffered by the National Front for the Liberation of Southern Vietnam (NLF, or Viet Cong) and its armed wing, the People’s Liberation Armed Forces (PLAF), in particular during the 1968 Tet battles. And Hanoi did acknowledge that, after Tet, the “political and military struggle in the rural areas declined and our liberated areas shrank.” Yet the allies came up decidedly short in achieving their 1969 Combined Campaign Plan goals. Thanks to increased communist infiltration rates along the Hồ Chí Minh Trail, MACV was unable to “inflict more losses on the enemy than he can replace,” for years a goal of the Americans and South Vietnamese.Footnote 14 (Abrams also had to contend with political fallout from costly military engagements, like the one suffered at Hamburger Hill in May 1969.) Senior US officers grumbled that combined operations between the two allies remained “superficial” at best. The US ambassador to South Vietnam, Ellsworth Bunker, additionally worried about the Saigon government’s post-Tet “crisis of confidence.” All the while, Abrams continually looked over his shoulder for the first announcement of American troop withdrawals he knew was coming soon.Footnote 15

The rising infiltration rates along the Hồ Chí Minh Trail – over 100,000 fresh troops entered South Vietnam in 1970 alone – intimated the war’s changing character to more conventional operations. Still, Abrams sensed an opportunity to strengthen a key pillar of his “one war” approach. With the NLF’s armed forces dispersed and demoralized after Tet, their credibility damaged, MACV initiated an “accelerated pacification campaign” in hopes of recovering lost ground. As in the past, though, such plans relied on brutal tactics which seemed only to further unravel South Vietnam’s social fabric. Those living in rural areas saw their homes destroyed and crops demolished, while refugee numbers surged and food shortages increased. In Abrams’ headquarters, senior military planners were coming to a grim realization. Temporary gains in violent pacification were one thing; long-lasting successes in genuine security and nation-building, quite another.Footnote 16

The inconclusive returns on pacification investments denoted unresolved issues in assessing the political aspects of this vital program. How could MACV nurture and evaluate the political loyalties of the rural population, not to mention those living in urban areas? Senior US officers never reached consensus. While one general argued that “by 1970 we had really begun to make pacification work,” others were far less sanguine. One corps commander thought that socioeconomic development was “the area of greatest failure” within pacification programs, while another three-star general believed the campaign against the insurgency’s political infrastructure was “somewhat disappointing.”Footnote 17 Moreover, diminishing popular support for the NLF did not necessarily translate into increased cooperation with South Vietnam’s government. Coercive pacification may have damaged the communist insurgency’s political network, the so-called Viet Cong infrastructure, but it did not help cultivate bases of support for the Nguyễn Vӑn Thiệu regime in Saigon. All told, it is difficult to accept Nixon’s claims that pacification “worked wonders in South Vietnam.”Footnote 18

North of the demilitarized zone, Hanoi also faced uncertainty after its failure to achieve a decisive military victory in 1968. Lê Duẩn, the Politburo’s general secretary, grudgingly embraced a more restrained “talking while fighting” policy that accentuated the war’s diplomatic aspects. With the NLF/PLAF losing 80 percent of its fighting force during the Tet battles, he had little choice. Thus, in 1969, the communists reverted to guerrilla operations and terrorist attacks, forcing Abrams to adjust by increasing small-unit patrolling across much of South Vietnam. Moreover, communist party leaders now had a morale problem on their hands. A political cadre wrote of a situation that had “deteriorated alarmingly, just like soap bubbles exposed to the sunlight.”Footnote 19 Another admitted that “1969 was the worst year we faced. … There was no food, no future – nothing bright.” No wonder that summer communist cadres launched a “wave of political training” to help maintain the revolutionary spirit. If Hanoi was going to sustain the war effort, military actions needed to be more cautious while Politburo leaders reemphasized the struggle’s political dimensions.Footnote 20

A sense of renewed stalemate pervaded both sides as the long Tet Offensive played out through 1968 and began anew with a fresh, though much diminished, communist offensive in early 1969. As bad as the struggle in South Vietnam appeared from the NLF perspective, there were few bright spots within MACV assessments. US casualties throughout the post-Tet period remained high. Indeed, in February 1968 alone, there were 2,124 Americans killed in action, the highest monthly total to that point in the war. Worse, Department of Defense analysts concluded that after the 1968 offensives, the “communists held the basic military advantage in South Vietnam because they could change the level of American battle deaths by changing the frequency and intensity of their attacks.” If Abrams truly was fighting a better war, it seems worth asking why the communists continued to hold the tactical initiative despite major setbacks during and after the Tet Offensive.Footnote 21

By early 1969, Abrams also had to confront major political decisions leading to the first withdrawal of US troops from Vietnam that spring. While MACV focused on improving the capabilities of South Vietnam’s defense forces, White House officials pressed Abrams for plans to redeploy his soldiers back home. The ensuing debates over how best to “de-Americanize” the war ultimately would pit Abrams against the Nixon administration and bring to surface civil–military tensions that would bedevil American leaders for the war’s remainder. Perhaps the most vocal advocate for Vietnamization was Secretary of Defense Melvin Laird. A former Wisconsin congressman, Laird realized the limits of domestic public support sustaining the administration’s Vietnam policies. Both he and the president realized, in Nixon’s words, the “reality” of “working against a time clock.” Not surprisingly, Abrams campaigned for more time – for pacification efforts to take hold; for improvements in training South Vietnamese regional and popular forces; for more military operations against communist forces. The White House, however, only became increasingly frustrated with a senior general who appeared to be dragging his feet.Footnote 22

Care should be taken in judging Abrams too harshly here. Neither he nor his chief subordinates were able to evaluate accurately how well South Vietnamese forces would perform once their American allies departed. After Tet, as Abrams reported, all they understood was that there were “major changes in the relationship between supported and supporting.” One senior officer recalled that a “confusing ambiguity surrounded the concept of Vietnamization.”Footnote 23 All the while, and much to Abrams’ chagrin, the CIA and MACV staffs reached vastly different conclusions over how well their Vietnamese partners were progressing. It did not help matters that neither agency accurately could predict the pace of US withdrawals or changes to the enemy’s military strategy. To a concerned Abrams, it appeared as if the Americans were departing faster than their allies could improve. He was not alone. A 1974 survey of over 170 US Army generals found that a full 25 percent were “doubtful” that South Vietnam’s armed forces would survive a “firm push” by communist forces in the near future.Footnote 24

Such misgivings put into question how well MACV was accomplishing its Vietnamization mission. Laird most certainly wondered. In the summer of 1969, he encouraged revising Abrams’ mission statement to better reflect changes in Nixon’s policies and to better show “what our forces in Southeast Asia are actually doing.” In mid-August, the administration handed MACV new orders. Instead of defeating the enemy and forcing its withdrawal from South Vietnam, as had been the objective during the Johnson years, MACV now would provide “maximum assistance” to its Vietnamese allies. The goal no longer was military victory. Rather, Abrams would provide support – to Vietnamization, to pacification, and to reducing the flow of supplies to the enemy – so South Vietnam’s people could “determine their future without outside interference.” As one veteran recalled, Abrams was taking on an “unenviable job.” Far from MACV headquarters, US soldiers and marines still out on combat missions began speculating how their continued exposure was worth the risks if victory no longer remained the goal.Footnote 25

Abrams’ first year in command left fundamental problems unresolved and a crucial question unanswered – how durable was the Saigon regime? No one knew. As the New York Times reported in June 1969, the “South Vietnamese armed forces appear to be doing a better job in battle now than ever before, but the day when they will be able to stand alone does not seem to be in sight.” A chasm remained between rural and urban areas, holding vast social consequences for a Thiệu government searching for some sense of political stability. Indeed, photojournalist Larry Burrows found that an “extraordinary cynicism pervades South Vietnam.”Footnote 26 Nor could any senior US officials find consensus over the true level of security in the Vietnamese countryside. In one province alone, Quảng Trị, MACV identified at least nine communist infantry regiments in June 1969. Thus, either from a social, political, or military standpoint, these early years of what Abrams deemed a “rearguard action” left Americans no closer to determining whether or not they ultimately would achieve “victory” in Vietnam.Footnote 27

Nixon’s Turn: Expanding a War to Withdraw from It

Richard M. Nixon recalled that when he first entered office, he “knew a military victory alone would not solve our problem” in Vietnam. Intent on changing the United States’ relationship with China and the Soviet Union, the new president recognized he could not simply abandon the long-standing US goal of supporting an independent, noncommunist South Vietnam. Yet both Nixon and his national security advisor, Henry Kissinger, understood the stalemated Southeast Asian conflict was doing little more than exhausting American resources. (The war’s cost then was approaching $30 billion annually.) These inherent tensions, if not contradictions, would be a hallmark of Nixon’s Vietnam strategy. The president sought to combine diplomatic initiatives with “irresistible military pressure” to win the war, yet simultaneously disengage from a conflict no longer central to United States foreign policy.Footnote 28

Hoping to alleviate these policy tensions, Kissinger established a special studies group evaluating the war while Nixon issued National Security Study Memorandum 1 (NSSM 1) directing key agencies to report on their prognoses. The results were far from encouraging. None of the key respondents – the Department of State, the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCF), the CIA, or MACV – agreed on much. Optimists believed the enemy had suffered crippling losses over the past two years, providing the United States an advantage in any forthcoming peace negotiations. Skeptics saw a stalemated conflict from which a compromise settlement was the likeliest outcome. Only on one major point did the agencies concur. The South Vietnamese armed forces would be unlikely to withstand a concerted enemy attack without continued American support. Kissinger admitted the NSSM 1 process shed light on the underlying “perplexities” of assessing the war in Vietnam and came to a grim conclusion: “There was no consensus as to facts, much less to policy.”Footnote 29

Nixon, however, did not wait for Kissinger’s results before laying out a comprehensive strategy. The president believed time favored the communists, who, despite losing the battlefield initiative, could continue the war and keep inflicting casualties on American forces. Worse, as US News & World Report surmised in June 1969, little evidence existed that Hanoi intended to abandon the fight. As Nixon told his National Security Council (NSC) staff that March, “We must move in a deliberate way, not to show panic.” Deliberate he was, at least in design. The president’s resultant five-point plan covered a wide range of initiatives – Vietnamization, pacification, diplomatic isolation of North Vietnam, the gradual withdrawal of US troops, and peace negotiations. As Nixon recalled, his strategy aimed to “end the war and win the peace.”Footnote 30 Yet the very comprehensiveness of such an approach generated its own set of problems. Foremost among them, how could Abrams successfully balance the competing demands of such an all-encompassing strategic construct?

Kissinger shared Abrams’ concerns over US troop withdrawals, fearing cuts in combat strength might weaken his negotiating position with Hanoi diplomats. (They treated negotiations only “as an instrument of political warfare,” Kissinger fumed.) Nixon squared this strategic circle by quietly expanding the war outside South Vietnam’s borders. In March, he authorized the “secret” bombing of North Vietnamese sanctuaries inside Cambodia. Congress was not consulted for fear of igniting protests at home. For the next fourteen months, B-52 bombers dropped more than 100,000 tons of munitions on the nominally neutral country. To keep Operation Menu covered, the administration falsified military records. On May 9, 1969, though, William Beecher of the New York Times broke the story. While Nixon was “pressing for peace in Paris,” the new president also was “willing to take some military risks avoided by the previous administration.” Beecher failed to mention that both Nixon and Kissinger worried how a lack of progress in Vietnam might damage US credibility abroad, a key component, they believed, in altering Cold War relationships with China and the Soviet Union.Footnote 31

If Abrams hoped the Cambodian bombing meant Nixon would allow him to settle the war on the battlefield, he soon would be disappointed. During a June trip to Midway Island, Nixon announced his decision to withdraw the first 25,000 American troops from Vietnam. The following month, now in Guam, the president declared his “Nixon Doctrine,” arguing that the United States must avoid “the kind of policy that will make countries in Asia so dependent upon us that we are dragged into conflicts such as the one that we have in Vietnam.” The announcement left little doubt over where the larger political currents were leading. If the United States was not disengaging from Asia, it certainly was expecting allies there to manage their own security problems. Later in the year, the president addressed the nation on his Vietnamization plans. During a November speech, Nixon was clear – the “primary mission of our troops is to enable the South Vietnamese forces to assume the full responsibility for the security of South Vietnam.” Though he proclaimed the United States would neither betray its allies nor let down its friends, Nixon’s address hardly inspired confidence within the Thiệu regime. Sooner, rather than later, the Americans were leaving South Vietnam behind.Footnote 32

Still, grave concerns over the long-term viability of South Vietnam’s government and armed forces convinced Nixon to go on the offensive. Cambodia proved an inviting target. The overthrow of Prince Norodom Sihanouk by Marshal Lon Nol in March 1970 served Nixon well, for the president could argue he was assisting Cambodia in aligning more closely with the United States. In truth, Nixon hoped to destroy North Vietnamese supply caches and troop sanctuaries along the Hồ Chí Minh Trail just outside of South Vietnam’s borders. Naturally, these goals were related to the president’s withdrawal plans. As the MACV command history relayed, the Cambodian operation was “a catalyst allowing the U.S. to meet more readily its 1970 goals … to continue to Vietnamize the war, lower the number of U.S. casualties, withdraw U.S. forces on schedule, and stimulate a negotiated settlement of the war.” This regionalization of the conflict came not just from Nixon’s fears that “North Vietnam was threatening to convert all of eastern Cambodia into one huge base area,” but from a consensus among Americans that a continuing military stalemate was undermining the entire Vietnamization effort.Footnote 33

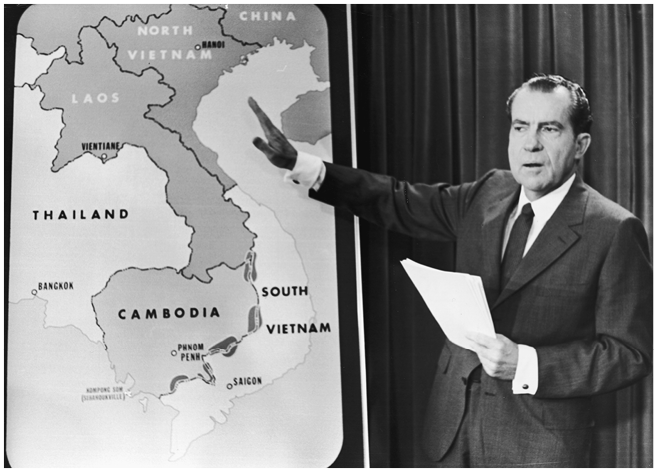

Figure 2.1 Richard Nixon points to a map of Southeast Asia during a nationwide broadcast on the Vietnam War (April 1970).

On April 30, 1970, American and South Vietnamese forces, part of a joint “spoiling attack,” assaulted into the bordering Parrot’s Beak and Fishhook regions of Cambodia. Though expecting the communists would stand and fight to defend their supply caches, the allies quickly found the evasive North Vietnamese retreating farther into Cambodia. Hopes of a decisive military victory quickly evaporated. Disappointed, the allies took comfort in the massive quantities of enemy supplies they had uncovered and destroyed. By MACV accounts, they had captured over 22,000 individual weapons and some 14 million pounds of rice. Nixon believed the operation “dealt a crushing blow to North Vietnam’s military campaign,” while senior military officers judged the incursion “extraordinarily successful.”Footnote 34

Other indicators suggested far more mixed results. Despite the operation’s successes, MACV admitted “problems in security persisted” and that “the enemy was not directly affected by the Cambodian incursion.” Lê Duẩn agreed, reporting in July that “our position on the whole battlefield has been maintained.”Footnote 35 Worse for Nixon, a political firestorm erupted back home when the president addressed the nation as the operation began. A reignited antiwar movement swept across college campuses, with Ohio National Guardsmen killing four students at Kent State and police killing two others at Jackson State University in Mississippi. Congress responded by prohibiting the use of US ground troops outside South Vietnam’s borders, repealing the 1964 Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, and forcing Nixon to set a June 30 deadline on operations inside Cambodia. In the Senate, Frank Church (D-Idaho) protested that “the Nixon administration has devised a policy with no chance of winning the war, little chance of ending it, and every chance of perpetuating it into the indefinite future.”Footnote 36

Unrest on the homefront, however, did not subvert worries inside the White House or MACV headquarters over the strategic balance within South Vietnam, leading to plans for yet another expansion of the war, this time into Laos. Abrams, in particular, hoped an attack on the Hồ Chí Minh Trail would disrupt communist designs for future offensive operations. Yet few policymakers asked how such an assault would solve more pressing problems. As Abrams’ own command historian noted, the challenges of 1971 – “the need to stabilize the economy, the need to continue progress in restoring security and tranquility to the countryside” – were “crucial” to Saigon’s existence. Would an attack into Laos resolve these internal, existential crises? Nor did contemporary military observers grant how rising enemy activity just outside South Vietnam’s borders revealed the temporary nature of allied achievements in Cambodia. Rather, senior commanders like Abrams seemed preoccupied with protesting Nixon’s decision to speed up troop withdrawal timetables to help quiet dissent at home. Once more, civil–military relations were wearing thin.Footnote 37

The subsequent incursion into Laos in early 1971, dubbed Operation Lam Sơn 719, only heightened questions about Vietnamization’s long-term prospects. Maneuvering alone – the 1970 Cooper–Church Amendment forbade US troops from fighting inside Cambodia or Laos – South Vietnam’s armed forces struggled against tenacious PAVN defenders. With rising casualties and over Abrams’ fierce opposition, President Thiệu prematurely halted the offensive, while American aircrews and artillery batteries did their best to cover what journalists soon were calling a “rout.” Nixon, then and later, railed against an unaccommodating media. But soldiers throughout the allied command structure knew they had been dealt a serious blow. One senior US officer reported to Abrams in April that enemy activity remained a “hindrance” to Saigon’s pacification efforts. A South Vietnamese general admitted Lam Sơn had created a “disquieting impact on the troops and population alike.” One young American GI offered a more prosaic critique. To him, the South Vietnamese “got their ass kicked and they are hightailing it back. It’s like us saying, ‘Pack up and run for your life. Everything is going according to plan.’”Footnote 38

That plan – a “splendid project on paper,” Kissinger later quipped – certainly sought additional time for Vietnamization to take hold and cover the ongoing American withdrawal. Larger assessments of the incursion, however, were not necessarily linked to the pace of these US troop redeployments. Indeed, no one seemed to agree on the outcome. Abrams told the press that Lam Sơn 719 was a “milestone in the development of the Armed Forces of the Republic of Vietnam.” Yet senior officers believed the operation “demonstrated exactly the opposite.”Footnote 39 General Donn A. Starry, a member of Abrams’ staff, recalled instead a sense of stalemate, arguing the “year 1971 was not successful to either side.” The disparity in opinions proved inconsequential. In mid-March, Secretary Laird announced that the administration considered itself “committed” to “at least the current rate of troop withdrawal from Vietnam through late 1972.” As the Washington Post reported, Laird did not tie the withdrawal rate to “progress on the battlefield or at the Paris Peace Talks.” The announcement should have elicited a fundamental inquiry. Did the incursions into Cambodia and Laos matter if Nixon was bringing troops home regardless of their results?Footnote 40

Observers in Hanoi thought so. To hawks like Lê Duẩn, Lam Sơn 719 highlighted stark deficiencies within South Vietnam’s armed forces, despite years of American tutelage. That summer, the Politburo debated a strategic offensive aimed at defeating Nixon’s Vietnamization policy, gaining a “decisive victory in 1972,” and forcing the American “imperialists to negotiate an end to the war from a position of defeat.” Yet Hanoi policymakers also had to account for the US rapprochement with China. Would Beijing pressure their North Vietnamese neighbors to accept a compromise peace settlement, given its new relationship with the United States? Thus, all signals pointed to a renewed offensive posture. Abrams had only 158,120 US troops at his disposal by the end of 1971. The South Vietnamese seemed like paper tigers. Antiwar activity on the American homefront apparently provided leverage in diplomatic negotiations. And Nixon’s overtures toward Beijing threatened to neutralize a key ally. Ultimately, Lê Duẩn had little difficulty convincing Politburo members of the need to strike sooner rather than later.Footnote 41

Hanoi intended its 1972 Easter Offensive to deal South Vietnam’s armed forces a crippling blow, forcing the United States to accept a negotiated settlement and a complete withdrawal from Vietnam. Unlike the 1968 Tet Offensive, the North Vietnamese would not seek a general uprising in Southern cities. Rather, the more conventional assault would occur in three phases. On March 30, communist forces struck South Vietnam’s northern provinces, followed soon thereafter by an attack into the Central Highlands. Lastly, PAVN troops would charge across the Cambodian border into Bình Long province and toward the provincial capital of An Lộc. While the communists struggled to coordinate three separate, slashing offensives, deep-rooted problems surfaced within the South Vietnamese ranks. American officers complained of the defense being “hampered by command and control difficulties.” Vietnamese officers refused to report bad news, impeding an effective response to the communists’ assault. Worse, from Abrams’ standpoint, the only remaining, reliable weapon at his disposal was American air power. The Easter Offensive’s opening rounds did not portend well for the future of South Vietnam.Footnote 42

As a deadly spring wore into summer, the situation inside South Vietnam began to stabilize. American air power took a deadly toll on the North Vietnamese invaders. One likened B-52 carpet-bombing to a “typhoon with trees crashing down and lightning transforming night into day.” Nixon once more escalated the war, launching an aerial assault against Hanoi and mining the northern port city of Hải Phòng. Once more, civil–military relations frayed as Abrams and the president clashed over the best use of air power. And once more, disparate assessments followed in the wake of battlefield actions. William Colby, MACV’s chief of nonmilitary programs, believed the South Vietnamese had met the test. “On the ground in South Vietnam,” he claimed, “the war had been won.” Yet contemporary accounts suggested otherwise. Abrams believed his allies’ force structure was “not adequate” to accomplish its mission without continued American support. Senior US advisors were dismayed by their counterparts’ leadership throughout the Easter Offensive. Perhaps most importantly, the communists now controlled more of South Vietnam’s territory than they did before the campaign began.Footnote 43

As Kissinger parried with Hanoi envoys in Paris that summer, there seemed little doubt Saigon would struggle in a future without direct US assistance. According to Kissinger’s military aide, Alexander M. Haig, President Thiệu’s intransigence at the negotiating table came from “being asked to relinquish sovereignty” over a large portion of his country. In fact, Hanoi’s diplomats sought a “standstill ceasefire” that would leave their troops in South Vietnam after the Americans departed. (They succeeded.) Moreover, the Nixon administration quietly altered its long-range goals, with Kissinger recommending to the president that their aim should be to “give the South Vietnamese [a] reasonable chance” to meet future attacks. The national security advisor failed to offer any guarantees.Footnote 44

Far from the White House that summer, rural South Vietnamese were asked by US advisors when they thought the war might end. Over 50 percent of respondents replied they did not know. Apparently, not only the Americans were unable to determine how their war would conclude.Footnote 45

Soldiering on toward an Uncertain End

Ever since the 1968 Tet Offensive – which many onlookers claimed was a military victory yet political defeat for the Americans and their allies – US soldiers and marines in Vietnam were asking similar questions about who was winning or losing. Nixon’s decision to initiate troop redeployments only exacerbated their uncertainties. One senior officer expressed a “great deal of reservation” about the “yardsticks” MACV was using to measure success. Another described the war as “a continuing crisis up to the bitter end.”Footnote 46 Meanwhile, troops in the field, watching their friends head home for good, wondered if any progress was being made at all. An advisor in Hậu Nghĩa province believed rural development plans were going forward, “but it is only occupation, not pacification.” Farther to the north, in Phú Yên province, another advisor, Major Eugene E. Fluke, described the local security apparatus as “more sieve than shield.” All the while, attitudes among the rank and file seemed to be shifting. As one Special Forces officer recalled, the emphasis became “Let’s get the damn thing over. Let’s close it out, with as much dignity as we can, but let’s just back off and come home.”Footnote 47

Without a clear grasp of the war’s trajectory, soldiers increasingly turned sour on a conflict many came to despise. Abrams fretted to his staff about maintaining the “fighting spirit” of remaining combat forces, while MACV’s command historian indicated that redeployment schedules were generating heightened morale problems. A December 1970 Newsweek editorial suggested “it might be a good idea to accelerate the rate of withdrawal,” in large part to alleviate mounting disaffection among the ranks. Only one month later, the 101st Airborne Division’s commander reported he had to direct “more time and energy to problems of morale and discipline.” Thus, while officers worried about maintaining a “keen combat edge,” soldiers and marines still on the front lines gradually began to turn against a war that, to them, was only “dragging on.” If Abrams indeed was fighting a “better war,” those under his command were not persuaded.Footnote 48

Leadership concerns over indiscipline in the ranks quickly made their way into the press. The New York Times reported on mounting drug use, citing surveys which suggested one in six enlisted men were “habituated users of marijuana.” John Steinbeck IV, son of the great novelist, went further, arguing in his 1968 article “The Importance of Being Stoned in Vietnam” that 75 percent of soldiers regularly got high.Footnote 49 Three years later, Newsweek editorialized on the “troubled” army in Vietnam, beset by an “increasingly lax attitude” among the men and soaring rates of fratricide. Incidents of “fragging” – termed from lobbing fragmentation grenades at “overly aggressive” officers – entered the war’s lexicon. In fact, in 1971 alone, an extraordinary 222 assaults took place. Along with rising desertion rates, such numbers suggested that enlisted men were losing faith in their chains of command with the war winding down. Officers might blame “permissive” civilian attitudes as the army “tried to cope with changing societal attitudes,” but even Abrams knew MACV had a “real problem” maintaining combat effectiveness.Footnote 50

Moreover, a sense of political consciousness among young draftees, coupled with potent domestic antiwar sentiment, gave rise to the Vietnam Veterans Against the War (VVAW). The grassroots organization boasted more than 25,000 members by the end of 1972 and forcefully countered claims of the war’s successful prosecution. Their sentiments were difficult to ignore. Prowar advocates might dismiss a long-haired “hippie” at Woodstock. It was harder to scorn a disabled veteran throwing away his medals in front of the US Capitol, as some 800 veterans did in the spring of 1971. The VVAW gained national attention, and influence, as it staged protest marches across the country, coordinated activities with other antiwar organizations, and voiced its concerns to members of Congress. Nixon claimed antiwar activists were “not acting out of moral convictions,” but VVAW dissenters clearly spoke with authority. When Lieutenant John Kerry presented testimony to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee in April 1971, he cogently argued that policymakers were engaging in “the height of criminal hypocrisy” by alleging US national security was threatened in South Vietnam.Footnote 51

The linkages between stateside and front-line resistance also could be found in matters of race. Clarence Fitch, an enlisted African American marine, expressed the porous boundaries between the civil rights movement at home and the war in Southeast Asia. “We weren’t living in no vacuum in Vietnam. There was a certain growing Black consciousness that was happening in the States, and also over there in Vietnam.” Fitch was right, and senior military leaders knew it. Many winced at the visible symbols of racial pride, the Black Power flags, the “dap” hand gestures among “brothers,” and the penchant for racial separation in the barracks and off duty.Footnote 52 Not surprisingly, those same leaders, most of them white, believed the army’s race problems were caused either by civilian influences or by a “hard core of militants” like the Black Panthers. By late 1969, senior Pentagon officials investigating racial unrest found a “pervasive problem throughout the armed forces.” While white officers tended to blame civilian society for their ills, most Blacks in the enlisted ranks pointed to the discriminatory administration of military justice as the greatest source of systemic racism.Footnote 53

Certainly, racism was not confined within the US armed forces, as several Americans lashed out against Vietnamese civilians in ways clearly undermining MACV’s pacification and civic action plans. Hyperaggressive basic training techniques and Cold War cultural norms both contributed to beholding the Vietnamese as “other,” an “uncivilized” people not warranting the sacrifices of young GIs fighting on their behalf. These racial pressures led to some US troops employing the “Mere Gook Rule,” suggesting that any dead Vietnamese, friend or foe, could be counted as communist and added to that day’s body count. Americans even cast aspersions on their own allies, many viewing South Vietnamese soldiers as “losers” who “didn’t have any initiative whatsoever.” “They were a joke,” one GI recalled. “I despised the whole lot of them.” Looking back, it is no wonder pacification remained such a violent affair as US soldiers and marines tried to establish a sense of control in their areas. Envisioning the Vietnamese as inhuman, if not savage, facilitated violence against the civilian population.Footnote 54

From these attitudes, it was not a far step for some Americans to commit war crimes. The most infamous of these transgressions occurred in March 1968 with the Tet Offensive still raging throughout most of South Vietnam. The massacre of perhaps as many as 500 civilians at Mỹ Lai by soldiers from the US Army’s 23rd Infantry Division remained undisclosed until late 1969 when journalist Seymour Hersh broke the story. To critics, the murders highlighted the bankruptcy of US policy in Southeast Asia. Apologists, however, argued the mass killing symbolized the “brutalization that inevitably afflicts men at war.” In fact, Lieutenant William Calley, Jr., the only participant convicted of wrongdoing, garnered a wave of national support. According to one Newsweek poll, nearly 70 percent of Americans thought Calley a “scapegoat for the actions of higher officers.” Few, though, had access to the lieutenant’s psychiatric reports, in which Calley stated “he did not feel as if he were killing humans but rather that they were animals with whom one could not speak or reason.”Footnote 55

It would be wrong, however, to argue the Mỹ Lai massacre proves that US troops were ordered to “kill anything that moves” or that command policies directed them to exterminate civilians. Historians likely will not achieve consensus on the number of Americans who perpetrated war crimes in Vietnam. Still, it seems safe to agree with veteran Larry Fontana: “There were questionable soldiers serving there, but, by far, the majority of the infantrymen were good, decent men who were doing their jobs the best way they could.” While heavy-handed military operations like “Speedy Express” gained national attention for their focus on body counts, most GIs followed in the footsteps of veteran–novelist Tim O’Brien. O’Brien’s unit experienced the same frustrations as Calley’s, in the same locale, yet “never crossed the axiological line between rage and homicide.”Footnote 56

Nor had the armed forces in Vietnam completely collapsed in these final years, despite the pressures placed on them. Contemporary critics, seeking blame for a war they feared had not been won, hammered away at leaders and enlisted alike. Two former officers maintained “the Army in Vietnam had literally destroyed itself under conditions of minimal combat stress.” Another claimed that soldiers made it through their year by “shirking, loafing, playing, going AWOL, and refusing to enter combat.” Recent scholarship, however, finds these stories of collapse overblown. The army was not a cesspit of deserters, addicts, or murderers. Combat refusals, like those at Firebase Pace in the fall of 1971, certainly occurred during the withdrawal period. But, all told, the vast majority of GIs performed their duties in admirable fashion, even if many of them griped about fighting a war they saw as a “bad joke.”Footnote 57

Still, the countryside remained a dangerous space for those Vietnamese navigating through a decades-long civil war. Americans may have been contemptuous of their allies, but few understood the crushing weight of sustaining an “atrocious and endless” conflict that was “threatening Vietnamese society with total destruction.” As the war dragged on, South Vietnam’s economy was racked by inflation, leaving many soldiers feeling exploited by a corrupt government while their families suffered. In truth, many Southern-enlisted troops, without clear political ties to Thiệu’s regime, turned inward to protect loved ones in their home villages rather than outward to defend their embattled state. GIs may have seen their allies as “undependable,” but they lacked historical context. As one Southern general put it, with “the war lasting almost continuously since 1946, most Vietnamese, though considering it a scourge, had come to regard it as part of their lives.”Footnote 58

Perhaps this uncomfortable fact added to Americans’ uncertainty as they finally departed Southeast Asia. The Vietnamese, Northern and Southern alike, not they, ultimately would answer the question of how victory or defeat would be defined. Reflecting on his tour in early 1972, Major General John H. Cushman noted that “self-doubt” was “essential equipment for a responsible officer in this environment.”Footnote 59 His peers may not have wished to agree, but Cushman proved insightful. As the Americans withdrew from Vietnam, there was plenty of self-doubt to go around.

Conclusion

Creighton Abrams departed Vietnam in June 1972, the Easter Offensive fighting not yet concluded. That October, Congress confirmed him to replace Westmoreland as the US Army’s chief of staff. In Paris that same month, Henry Kissinger believed he finally had secured a negotiated settlement, but his public declaration that “peace is at hand” proved premature. In many ways, President Thiệu stood as the chief obstacle, fearing that his American allies had betrayed him and that he would be “committing suicide” if he signed any agreement leaving PAVN troops inside South Vietnam. Nixon, infuriated with the delays, once more launched an air campaign, Linebacker II, to serve as a warning to Hanoi and a pledge of support to Saigon. When the Paris Peace Accords were signed in January 1973, few South Vietnamese leaders were exultant. Vice President Nguyễn Cao Kỳ called the agreement a “sellout,” while Ambassador Bùi Diễm thought the Americans simply “wanted to wash their hands of the whole business and run.”Footnote 60

Kỳ and Diễm were not alone in their harsh appraisals. The war’s immediate legacy left many Americans wondering whether the United States had departed Vietnam as victor, vanquished, or just bloodied combatant from a dissatisfying stalemate. Newspaper editorials might have lauded Nixon for achieving “peace with honor,” but any applause was muted. In fact, no peace came to Vietnam. Within forty-eight hours of the Paris Agreement’s signing, the PAVN attacked over 400 Southern villages and hamlets. As the Boston Globe reported in April, “none of the Vietnamese are unloading their magazines or disarming their guns.” Territory once considered “pacified” quickly reverted to communist control. It soon became clear that Kissinger had neither obtained substantive concessions from Hanoi’s leaders nor convinced them to abandon their goal of unifying Vietnam under communist control.Footnote 61

Even before Saigon’s final collapse in April 1975, American political and military leaders were condemning others for their perceived failures. Nixon roared that Congress had snatched “defeat from the jaws of victory.” Retired generals cast blame on the media and antiwar activists. Others vented aspersions on unworthy South Vietnamese allies who supposedly lacked the will to fight. One senior admiral, U. S. Grant Sharp, even claimed that the communists had not won the war, but, rather, Washington politicians had lost it. It would become a common refrain within military circles for decades to come. And yet when army generals were surveyed after the peace agreement, nearly one-third believed the war’s results not worth the effort. Might it be that Abrams and his command, in fact, had not secured victory as they departed Vietnam?Footnote 62

The painstaking American withdrawal from Vietnam raises important questions for those evaluating US strategy in the final years of a long, bloody conflict. Why was it so difficult for civilian policymakers and senior military officers to accurately determine their progress during the war’s final stages? What were the implications when commanders and their troops were incapable of appraising whether they were winning or losing? Did alterations to MACV tactics and operational approaches influence, in any way, the final outcome? And, finally, how could commanders like Abrams convince their soldiers, and the larger American public, that their sacrifices were making a difference?

Back in late July 1970, Associated Press writer Michael Putzel offered a postmortem on the defense of Firebase Ripcord. Using words like “abandonment” and “retreat,” the story hardly extolled American military performance in the A Shau valley that summer. Putzel concluded with a tactical synopsis, arguing that the North Vietnamese, by “choosing the battlefield and measuring the objective against their probable casualties, could force the Americans or the South Vietnamese out of another, and yet another, of these mountaintop bases.” Ripcord, then, might be seen as a microcosm of the American war effort in Vietnam. In the end, it was the Vietnamese communists who retained the battlefield initiative, the capacity to influence the political–military situation inside South Vietnam, and the diplomatic leverage to shape a final negotiated settlement forcing the Americans from the war.Footnote 63