I. INTRODUCTION

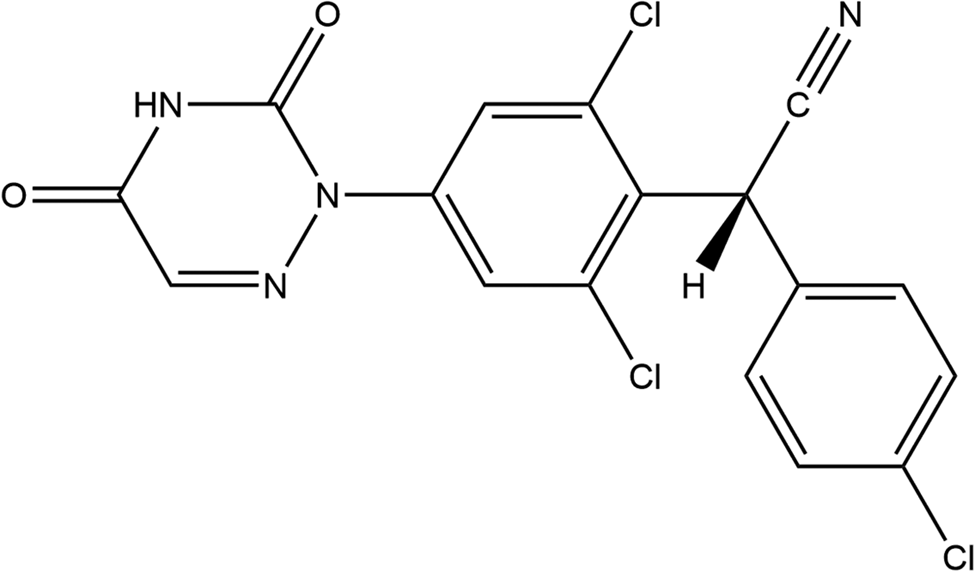

Diclazuril (sold under the brand names Protazil®, Vecoxan, and Clinacox) is an FDA-approved veterinary pharmaceutical (in the US) for equine protozoal myeloencephalitis (EPM) in horses and as a coccidiostat in broiler chickens. The systematic name (CAS Registry Number 101831-37-2) is 2-(4-chlorophenyl)-2-[2,6-dichloro-4-(3,5-dioxo-1,2,4-triazin-2-yl)phenyl]acetonitrile. A two-dimensional molecular diagram is shown in Figure 1. Some studies of diclazuril are summarized in Chapman et al. (Reference Chapman, Barta, Blake, Gruber, Jenkins, Smith, Suo and Tomley2013), but we are unaware of any published X-ray powder diffraction data on this compound.

Figure 1. The 2D molecular structure of diclazuril.

This work was carried out as part of a project (Kaduk et al., Reference Kaduk, Crowder, Zhong, Fawcett and Suchomel2014) to determine the crystal structures of large-volume commercial pharmaceuticals, and include high-quality powder diffraction data for them in the Powder Diffraction File (Gates-Rector and Blanton, Reference Gates-Rector and Blanton2019).

II. EXPERIMENTAL

Diclazuril was a commercial reagent, purchased from TargetMol (Lot #112009), and was used as-received. The white powder was packed into a 1.5 mm diameter Kapton capillary, and rotated during the measurement at ~50 Hz. The powder pattern was measured at 295 K at beamline 11-BM (Antao et al., Reference Antao, Hassan, Wang, Lee and Toby2008; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Shu, Ramanathan, Preissner, Wang, Beno, Von Dreele, Ribaud, Kurtz, Antao, Jiao and Toby2008; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Toby, Lee, Ribaud, Antao, Kurtz, Ramanathan, Von Dreele and Beno2008) of the Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratory using a wavelength of 0.458208(2) Å from 0.5 to 50° 2θ with a step size of 0.0009984375 and a counting time of 0.1 s per step. The high-resolution powder diffraction data were collected using twelve silicon crystal analyzers that allow for high angular resolution, high precision, and accurate peak positions. A silicon (NIST SRM 640c) and alumina (SRM 676a) standard (ratio Al2O3:Si = 2:1 by weight) was used to calibrate the instrument and refine the monochromatic wavelength used in the experiment.

The pattern was indexed using N-TREOR (Altomare et al., Reference Altomare, Cuocci, Giacovazzo, Moliterni, Rizzi, Corriero and Falcicchio2013) on a primitive monoclinic cell with a = 27.02114, b = 11.43736, c = 5.37083 Å, β = 91.810°, V = 1659.0 Å3, and Z = 4. A reduced cell search in the Cambridge Structural Database (Groom et al., Reference Groom, Bruno, Lightfoot and Ward2016) with the chemistry H, C, Cl, N, and O only yielded one hit, but no structures of diclazuril. The suggested space group was P2 1/a, which was confirmed by successful solution and refinement of the structure. A diclazuril molecule was downloaded from PubChem (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Chen, Cheng, Gindulyte, He, He, Li, Shoemaker, Thiessen, Yu, Zaslavsky, Zhang and Bolton2019) as Conformer3D_CID_465389.sdf. It was converted to a *.mol2 file using Mercury (Macrae et al., Reference Macrae, Sovago, Cottrell, Galek, McCabe, Pidcock, Platings, Shields, Stevens, Towler and Wood2020). The structure was solved by Monte Carlo simulated annealing as implemented in EXPO2014 (Altomare et al., Reference Altomare, Cuocci, Giacovazzo, Moliterni, Rizzi, Corriero and Falcicchio2013).

Rietveld refinement was carried out using GSAS-II (Toby and Von Dreele, Reference Toby and Von Dreele2013). Only the 1.8–30.0° portion of the pattern was included in the refinement (d min = 0.885 Å). All non-H bond distances and angles were subjected to restraints, based on a Mercury/Mogul Geometry Check (Bruno et al., Reference Bruno, Cole, Kessler, Luo, Motherwell, Purkis, Smith, Taylor, Cooper, Harris and Orpen2004; Sykes et al., Reference Sykes, McCabe, Allen, Battle, Bruno and Wood2011). The Mogul average and standard deviation for each quantity were used as the restraint parameters. The restraints contributed 4.2% to the final χ 2. The hydrogen atoms were included in calculated positions, which were recalculated during the refinement using Materials Studio (Dassault, 2021). The U iso of the heavy atoms were grouped by chemical similarity. The U iso for the H atoms were fixed at 1.2× the U iso of the heavy atoms to which they are attached. No preferred orientation model was necessary for this rotated capillary specimen. The peak profiles were described using the generalized microstrain model. The background was modeled using a 6-term shifted Chebyshev polynomial, and a peak at 5.72° 2θ to model the scattering from the Kapton capillary and any amorphous component.

The final refinement of 106 variables using 28 245 observations and 68 restraints yielded the residuals R wp = 0.0633 and GOF = 1.16. The largest peak (1.67 Å from C11) and hole (1.77 Å from C22) in the difference Fourier map were 0.31(7) and −0.33(7) eÅ−3, respectively. The largest errors in the difference plot (Figure 2) are very small.

Figure 2. The Rietveld plot for the refinement of diclazuril. The blue crosses represent the observed data points, and the green line is the calculated pattern. The cyan curve is the normalized error plot. The vertical scale has been multiplied by a factor of 8× for 2θ > 12.0°. The row of blue tick marks indicates the calculated reflection positions.

The crystal structure was optimized using density functional techniques as implemented in VASP (Kresse and Furthmüller, Reference Kresse and Furthmüller1996) (fixed experimental unit cell) through the MedeA graphical interface (Materials Design, 2016). The calculation was carried out on 16 2.4 GHz processors (each with 4 GB RAM) of a 64-processor HP Proliant DL580 Generation 7 Linux cluster at North Central College. The calculation used the GGA-PBE functional, a plane wave cutoff energy of 400.0 eV, and a k-point spacing of 0.5 Å−1 leading to a 3 × 2 × 3 mesh, and took ~127 h. A single-point density functional calculation (fixed experimental cell) and population analysis were carried out using CRYSTAL17 (Dovesi et al., Reference Dovesi, Erba, Orlando, Zicovich-Wilson, Civalleri, Maschio, Rerat, Casassa, Baima, Salustro and Kirtman2018). The basis sets for the H, C, and O atoms in the calculation were those of Gatti et al. (Reference Gatti, Saunders and Roetti1994), and that for Cl was that of Peintinger et al. (Reference Peintinger, Vilela Oliveira and Bredow2013). The calculations were run on a 3.5 GHz PC using 8 k-points and the B3LYP functional, and took ~1.8 h.

III. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

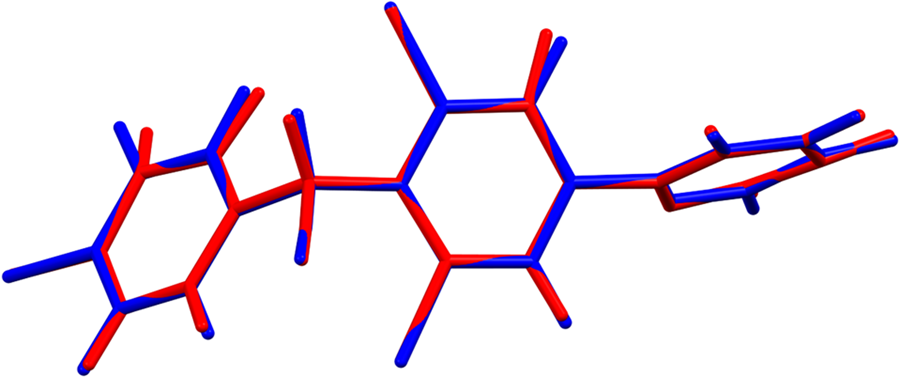

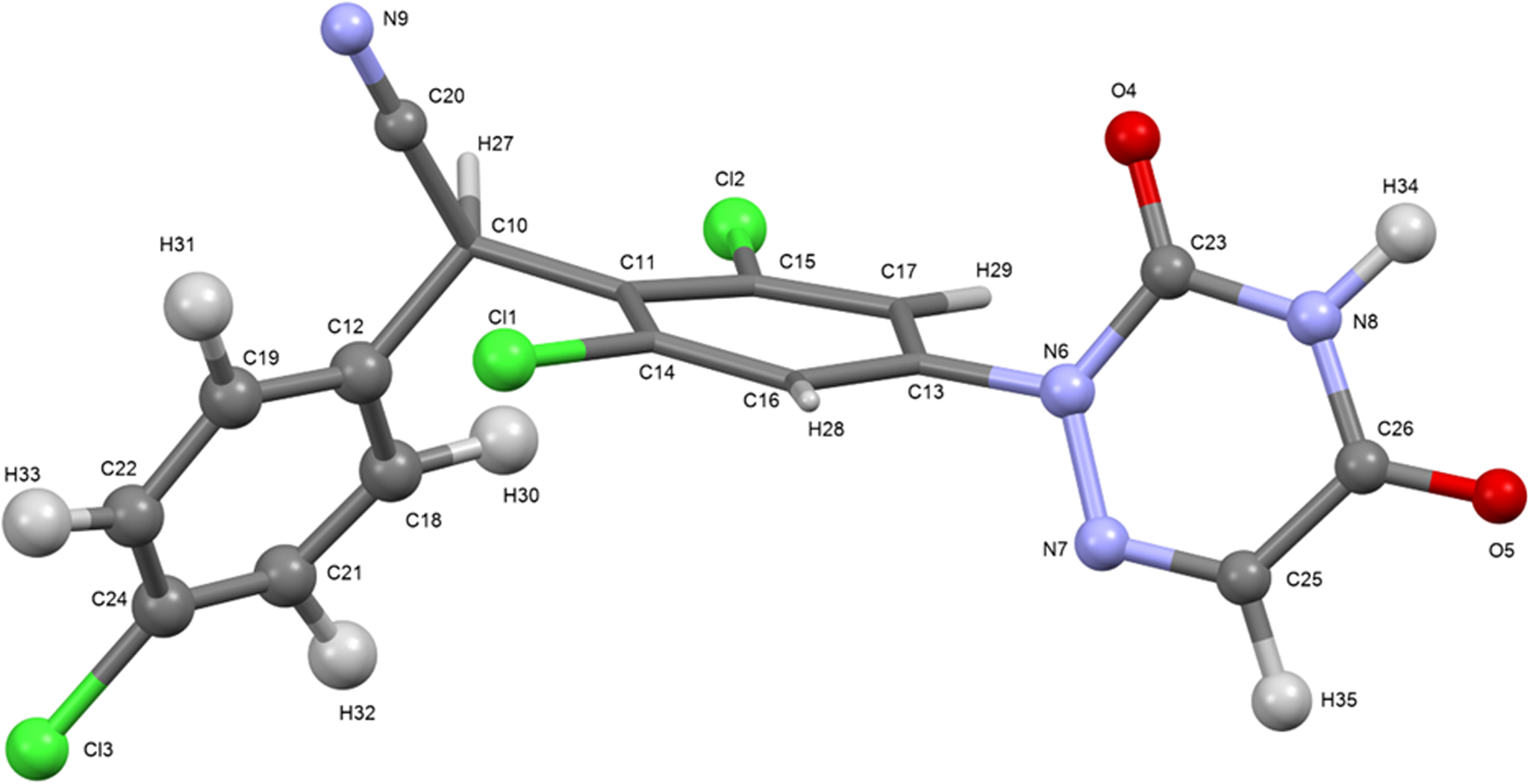

The root-mean-square (rms) Cartesian displacement between the Rietveld-refined and DFT-optimized structures of diclazuril is 0.051 Å (Figure 3). The excellent agreement provides strong evidence that the refined structure is correct (van de Streek and Neumann, Reference van de Streek and Neumann2014). This discussion concentrates on the DFT-optimized structure. The asymmetric unit (with atom numbering) is illustrated in Figure 4. The best view of the crystal structure is down the short c-axis (Figure 5). The crystal structure consists of layers of molecules parallel to the ac-plane.

Figure 3. Comparison of the Rietveld-refined (red) and VASP-optimized (blue) structures of diclazuril. The rms Cartesian displacement is 0.051 Å. Image generated using Mercury (Macrae et al., Reference Macrae, Sovago, Cottrell, Galek, McCabe, Pidcock, Platings, Shields, Stevens, Towler and Wood2020).

Figure 4. The asymmetric unit of diclazuril, with the atom numbering. The atoms are represented by 50% probability spheroids. Image generated using Mercury (Macrae et al., Reference Macrae, Sovago, Cottrell, Galek, McCabe, Pidcock, Platings, Shields, Stevens, Towler and Wood2020).

Figure 5. The crystal structure of diclazuril, viewed down the c-axis. Image generated using diamond (Crystal Impact, 2022).

All of the bond distances and bond angles fall within the normal ranges indicated by a Mercury/Mogul Geometry Check (Macrae et al., Reference Macrae, Sovago, Cottrell, Galek, McCabe, Pidcock, Platings, Shields, Stevens, Towler and Wood2020). The torsion angles involving rotation about the C13–N6 bond are flagged as unusual. For example, the C16–C13–N6–N7 angle of 74° lies on the tail of one part of a bimodal distribution of similar torsion angles, with peaks at ~40 and ~140°. These torsion angles indicate the angle between the triazine ring and one of the phenyl rings seems to be slightly unusual.

Quantum chemical geometry optimization of the diclazuril molecule (DFT/B3LYP/6-31G*/water) using Spartan ‘18 (Wavefunction, 2020) indicated that the observed conformation is 55.9 kcal mol−1 higher in energy than the local minimum. The major differences are in the orientations of the outer rings of the molecule. A conformational analysis (MMFF force field) indicates that the minimum-energy conformation is 21.1 kcal mol−1 lower in energy, but the molecule folds on itself to make the Cl-containing rings parallel. Intermolecular interactions are thus important in determining the solid-state conformation.

Analysis of the contributions to the total crystal energy of the structure using the Forcite module of Materials Studio (Dassault, 2021) suggests that the intramolecular deformation energy terms are small, but that torsion deformation terms are the largest. The intermolecular energy is dominated by electrostatic attractions, which in this force field analysis include hydrogen bonds. The hydrogen bonds are better analyzed using the results of the DFT calculation.

Hydrogen bonds are prominent in the structure (Table I). The most noteworthy is the strong N8–H34⋯O5 hydrogen bond, which links the molecules into dimers along the a-axis with a graph set R2,2(8) (Etter, Reference Etter1990; Bernstein et al., Reference Bernstein, Davis, Shimoni and Chang1995; Shields et al., Reference Shields, Raithby, Allen and Motherwell2000). The energy of the N–H⋯O hydrogen bond was calculated using the correlation of Wheatley and Kaduk (Reference Wheatley and Kaduk2019). The methyne carbon C10 forms an intramolecular C–H⋯Cl hydrogen bond. Intermolecular C–H⋯Cl and C–H⋯O hydrogen bonds also contribute to the lattice energy.

TABLE I. Hydrogen bonds (CRYSTAL17) in diclazuril

a Intramolecular.

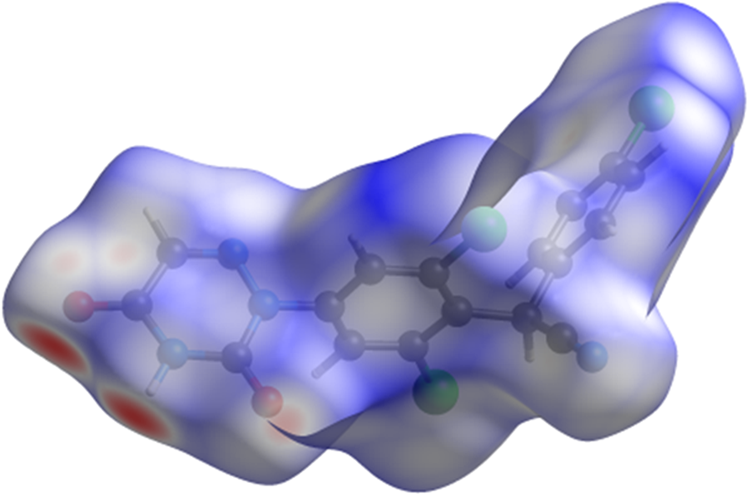

The volume enclosed by the Hirshfeld surface of diclazuril (Figure 6, Hirshfeld, Reference Hirshfeld1977; Turner et al., Reference Turner, McKinnon, Wolff, Grimwood, Spackman, Jayatilaka and Spackman2017) is 406.45 Å3, 98.14% of 1/4 the unit cell volume. The packing density is thus fairly typical. The only significant-close contacts (red in Figure 6) involve the hydrogen bonds. The volume/non-hydrogen atom is smaller than usual at 15.9 Å3.

Figure 6. The Hirshfeld surface of diclazuril. Intermolecular contacts longer than the sums of the van der Waals radii are colored blue, and contacts shorter than the sums of the radii are colored red. Contacts equal to the sums of radii are white. Image generated using CrystalExplorer (Turner et al., Reference Turner, McKinnon, Wolff, Grimwood, Spackman, Jayatilaka and Spackman2017).

The Bravais–Friedel–Donnay–Harker (Bravais, Reference Bravais1866; Friedel, Reference Friedel1907; Donnay and Harker, Reference Donnay and Harker1937) morphology suggests that we might expect elongated morphology for diclazuril, with [001] as the long axis. No preferred orientation model was necessary for this rotated capillary specimen.

IV. DEPOSITED DATA

The Crystallographic Information Framework (CIF) files containing the results of the Rietveld refinement (including the raw data) and the DFT geometry optimization were deposited with the ICDD. The data can be requested at [email protected].

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The use of the Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratory was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. This work was partially supported by the International Centre for Diffraction Data. We thank Lynn Ribaud and Saul Lapidus for their assistance in the data collection.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.