INTRODUCTION

Indigenous entrepreneurship in the Pacific has been the subject of much attention in recent decades, driven by the recognition that there are a range of noneconomic factors that play a central role in the success or otherwise of indigenous-owned businesses. Surprisingly, given the high proportion of land under customary forms of tenure across the region, there has been very little work that directly examines the significance of customary land as a social and cultural resource for indigenous business in the Pacific. In part this reflects the limited framing of business success among indigenous entrepreneurs in the Pacific, where external and donor criteria focus on financial viability. Broader criteria, taking into account social, cultural and environmental values of the community – which are encapsulated for instance, in the Fijian notion of vanua (Batibasaga, Overton, & Horsley, Reference Batibasaga, Overton and Horsley1999), are likely to produce a measure of ‘success’ that reflects the on-going importance of being embedded in land, and people’s enduring relationships to that land. Incorporating such values into an assessment of indigenous businesses is hence more meaningful to Pacific business owners and entrepreneurs than examining financial viability alone.

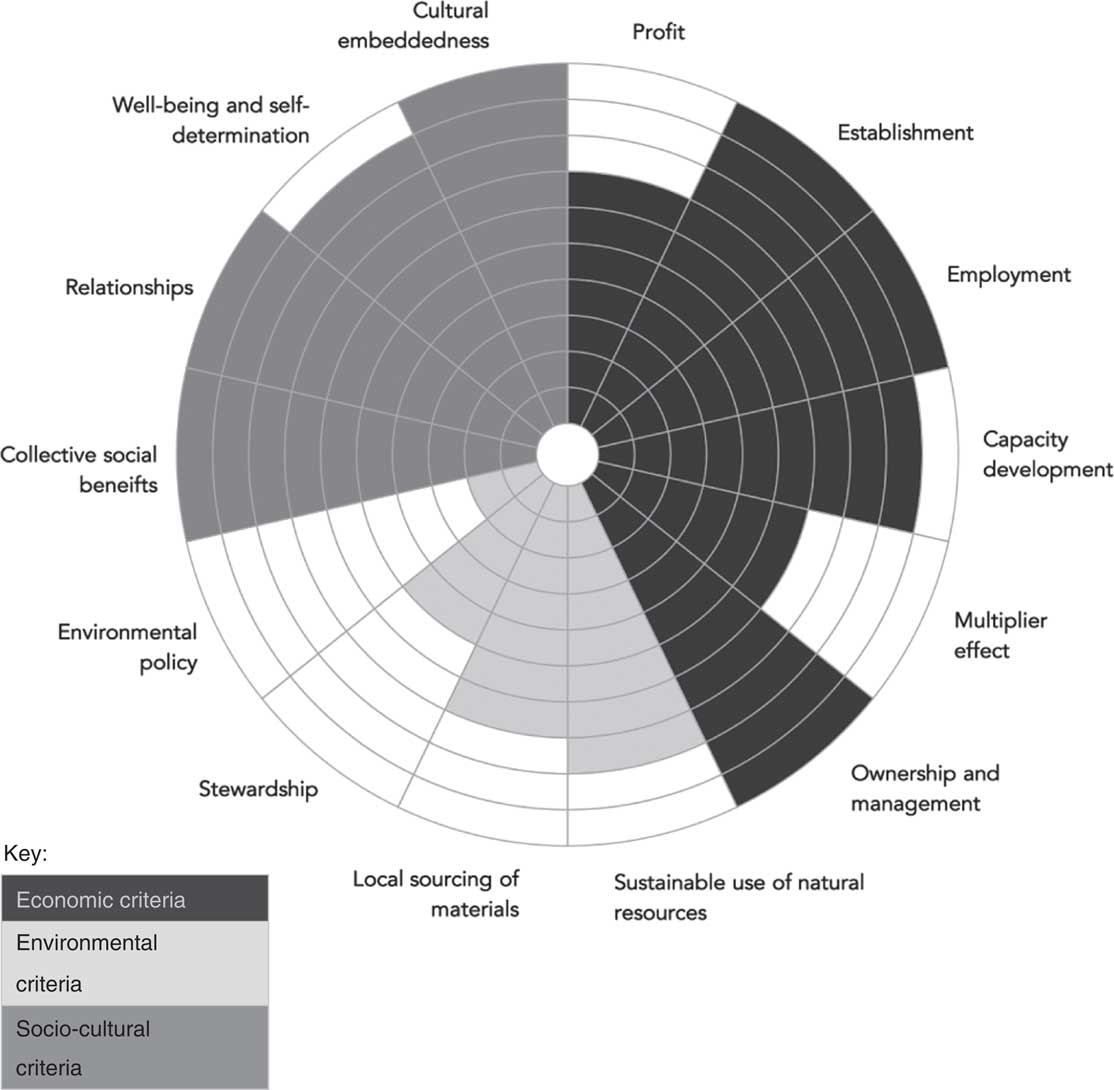

This brief overview opens with a discussion of the economic context of development in the Pacific as an introduction to the literature on entrepreneurship in the Pacific. We then explore the linkages between customary land and entrepreneurship, highlighting the close, integrated socio-cultural relationship between people, place, land ownership and economic activity in the Pacific. The paper then moves on to methodological questions and the development and initial application of a novel tool to assess the sustainability of indigenous, customary land-based businesses in the Pacific. Our graphic tool allows for the evaluation of a more complete range of business ‘sustainability success’ factors that reflect, at their core, the central importance of land, and people’s connections to the land, in Pacific societies. Specifically, it includes economic, socio-cultural and environmental measures. We conclude by arguing that culturally meaningful tools such as this are essential if the success and sustainability of indigenous entrepreneurship on customary land is to be measured in terms that make sense to Pacific communities.

THE NEED FOR A HOLISTIC APPROACH TO ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT AND ENTREPRENEURSHIP IN THE PACIFIC

Conventional theories on economics have long dominated national development policies globally. These national strategies are largely guided by economic models focussed on achieving economic growth, which is still widely accepted as the mainstream notion of development and progress. In particular, the linear stage models advocated by Rostow and Harrod-Domar were long considered as the basic templates in facilitating national economic growth (Anderson & Lee, Reference Anderson and Lee2010; Henderson, Reference Henderson2013), but they have been criticised more recently for their narrow focus on economic growth which can in fact deepen inequalities in society, their failure to capture notions of overall social well-being and for their unsustainable end goal of high mass consumption (Anderson & Lee, Reference Anderson and Lee2010; Raworth, Reference Raworth2017: 268). New, alternative notions of economic development that embrace social, environmental, cultural and monetary elements are starting to shake up such conventional thinking and offer new ways forward for planning development; a good example is Kate Rowarth’s Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st Century Economist (Raworth, Reference Raworth2017).

One problem with rigid, conventional economic theories is that underlying structures and processes rooted in particular cultural contexts, such as those of Pacific Island societies, are left unrecognised and thus, undervalued. Such activities, which are characterised in community interactions, kinship and relationships, also contribute to the dynamics of an economy, but are often overlooked due to their nonmonetary nature [see Gibson-Graham (Reference Gibson-Graham2005) and Curry & Koczberski (Reference Curry and Koczberski2012)]. Many people of the Pacific have a strong cultural upbringing which has reinforced social relationships as the centre of their formal, informal and noncash economic activities. Meeting social obligations, gift exchange and reciprocity are some of the cultural practices deeply embedded in their economic activities (Curry, Reference Curry2005; Curry & Koczberski, Reference Curry and Koczberski2012; Gibson, Reference Gibson2012); while they do not necessarily produce financial profit, they still possess significant economic value (Banks, Reference Banks2007; Curry & Koczberski, Reference Curry and Koczberski2012; Gibson, Reference Gibson2012; Leokana, Reference Leokana2014). These cultural practices underscore the importance of the relationships and associated cultural and social capital which enables access to crucial information and resources, and helps to maintain stability and resilience of people in the Pacific (Gilberthorpe & Sillitoe, Reference Gilberthorpe and Sillitoe2009).

Small businesses add much needed diversity to the subsistence sector of many Pacific Island countries, offering a means of earning cash for medical care, education, transport and basic household goods (Cahn, Reference Cahn2008). However, a lot of research on such businesses in the Pacific has had a negative focus, highlighting barriers to success and poor business practices. Certainly such businesses do face unique challenges associated with the small size of domestic markets, geographical isolation and poor transport infrastructure, particularly when they are located in remote and rural areas (Hailey, Reference Hailey1987; Cahn, Reference Cahn2008). Vulnerability to natural disasters, which appear to be increasing in frequency and/or intensity due to climate change, adds another significant challenge. Furthermore, it can be difficult for indigenous entrepreneurs to access suitable training, technical assistance or other support, and accordingly some small businesses are characterised by under-capitalisation, low turnover and poor cash flow (Saffu, Reference Saffu2003). Cultural barriers to business success have also been noted. Some assert that entrepreneurialism requires individualism, which is not a valued trait in collectivist Pacific Island societies (Duncan, Reference Duncan2008). It is also suggested that Pacific Island entrepreneurs find it difficult to reinvest in their business because of pressure to distribute any surplus revenue to meet family or communal obligations (Finney, Reference Finney1987). The expectation that free credit is provided to relatives, with no guarantee of repayment, can further damage cash flow.

While it is important to recognise these limitations faced by Pacific businesses, there are also positive cultural influences on their operations. For example, meeting communal obligations can also strengthen social capital and associated business resilience (Purcell & Scheyvens, Reference Purcell and Scheyvens2015). Similarly, businesses which give generous donations to community events generate goodwill towards their products and services. Gifting – for example, contributing to wedding or funeral expenses – can be a form of saving, safe in the knowledge that in times of need, it will be reciprocated. Thus our understanding of the potential of Pacific businesses needs to be based on an awareness of both the constraints faced by these businesses and the positive aspects of being a culturally embedded business.

Similar to the narrow focus of conventional economics, there is a Eurocentric or Ameri-centric and capitalist focus of much research on entrepreneurship, focussing on individuality and monetary success. The scholarship on entrepreneurship, however, is broadening with newer research on entrepreneurial practice acknowledging that it is ‘shaped by and profoundly effects, the culture within which it operates’ (Schaper, Reference Schaper2007: 526). Accordingly, indigenous people often develop their own styles of entrepreneurship which typically blend traditional culture and values with modern economic practices (Dana & Anderson, Reference Dana and Anderson2007). Research into indigenous businesses has found that they are often characterised by community-based development goals, collective organisation and a focus on environmental sustainability (Peredo & Anderson, Reference Peredo and Anderson2006: 265–257). It has thus been suggested that entrepreneurship will only be sustainable if done in a manner congruent with local social norms (Hailey, Reference Hailey1987; Saffu, Reference Saffu2003). Indigenous entrepreneurs are now being encouraged to develop their businesses in ways that show respect for their culture and that build upon indigenous knowledge, heritage and the notion of community (Hindle, Reference Hindle2010). As Spiller et al. explains, some New Zealand Māori businesses have managed to balance traditional customs with contemporary business practices through establishing business models that explicitly recognise and acknowledge the social connectedness and cultural embeddedness of the enterprise (Spiller, Erakovic, Henare, & Pio, Reference Spiller, Erakovic, Henare and Pio2011).

Furthermore, informal economic endeavours which are generally small-scale, unregulated and family-owned (Todaro & Smith, 2012: 328), are important in terms of generating income and sustaining livelihoods. They are, however, not generally considered part of the conventional market system even though they provide an entry point into business for many indigenous entrepreneurs and also generate economic growth. Entrepreneurship in the informal sector enhances the productive capacity of individuals and sustains people’s lives and well-being, especially when formal sector jobs are inaccessible, limited or unavailable (Duncan, Reference Duncan2008; Imbun, Reference Imbun2009). Many informal entrepreneurial activities would not exist without the existence of strong social capital.

Cultural values definitely inform the business practices and goals of indigenous enterprises in the Aotearoa New Zealand and the wider Pacific region (see e.g., Harmsworth, Reference Harmsworth2005; Lertzman & Vredenburg, Reference Lertzman and Vredenburg2005; Spiller et al., Reference Spiller, Erakovic, Henare and Pio2011; Kahui & Richards, Reference Kahui and Richards2014). For instance, research into 10 Solomon Islands businesses found that owners remained strongly influenced by their customary values and beliefs (Leokana, Reference Leokana2014). Most indigenous businesses are developed to improve family well-being and livelihood, rather than make financial profit, with economic well-being regarded as a means to fulfilling broader spiritual, cultural, social and environmental notions of well-being (Harmsworth, Reference Harmsworth2005). A study of 700 Pacific entrepreneurs found that in contrast to individualism and achievement, collectivist approaches were the norm for Pacific Island entrepreneurs (Saffu, Reference Saffu2003). Furthermore, research with entrepreneurs in Samoa found that development programmes seeking to assist indigenous entrepreneurs in the Pacific, for example, via business mentoring, will have a much greater chance of success if the mentors have a good understanding of the local cultural context, and of what Pacific entrepreneurs are striving to achieve – including their social and cultural priorities (Purcell & Scheyvens, Reference Purcell and Scheyvens2015).

CUSTOMARY LAND AND INDIGENOUS ENTREPRENEURSHIP IN THE PACIFIC

Land is conventionally understood in development discourse as a commodity and an economic asset, a notion long contested by Polanyi in his writing on ‘fictitious commodities’ (Reference Polanyi1944: 71). Certainly people of the Pacific view land in a more complex, holistic manner. Accordingly, words commonly translated as ‘land’ – such as vanua in Fiji, fonua in Tonga, enua in the Cook Islands, whenua in NZ (Batibasaga, Overton, & Horsley, Reference Batibasaga, Overton and Horsley1999) – embrace land and people and their connections. These terms are all-encompassing and include cultural, social and spiritual elements, along with people’s values, beliefs, traditions and history, all interlinked with the natural and supernatural world (Batibasaga, Overton, & Horsley, Reference Batibasaga, Overton and Horsley1999; Tuwere, Reference Tuwere2002; Nabobo-Baba, Reference Nabobo-Baba2006). Land’s ability to provide sustenance is also central to why it is valued and respected and is therefore essential to any consideration of its economic potential. Fundamentally, people of the Pacific have an ‘intense attachment to land’ (Curry, Koczberski, & Connell, Reference Curry, Koczberski and Connell2012: 116). This is particularly significant in the seven Pacific Island countries where customary land comprises more than 80% of the total land area (Boydell & Holzknecht, Reference Boydell and Holzknecht2003: 203).

Throughout the Pacific the values of the land are upheld by its people through cultural rituals and processes that honour the ancestors and physical and spiritual dimensions within the land. Departing from these values is believed to have negative consequences; stories abound of new developments on customary land that are understood to have failed because they did not progress in a culturally appropriate way. Accordingly, the Rotuman expression ‘The land has eyes and teeth’ (Hereniko, Reference Hereniko2006), speaks to the belief that vanua is a living being that watches (with its eyes) and manifests physically through illness, accident and even death (it has teeth). This phrase was heard, for example, when the Momi Bay tourism resort in Fiji faltered in 2008, leaving half-built bungalows and metre-high grass obstructing the $20 million golf course (Scheyvens & Russell, Reference Scheyvens and Russell2010: 20–21). The expression ‘the land has eyes and teeth’ thus points to people’s profound understanding of the power of the land and its mana (Māori term for honour/authority/prestige), which demands respect from all, from foreign investors through to indigenous entrepreneurs (see e.g., Tuwere, Reference Tuwere2002; Huffer & Qalo, Reference Huffer and Qalo2004). When Pacific Island entrepreneurs decide to pursue business plans based on customary land they thus tend to proceed cautiously to ensure that cultural protocols are respected.

External commentators regularly assert that customary practices around land ‘constrain’ economic development and impair investments in the Pacific (Prasad & Tisdell, Reference Prasad and Tisdell1996; Hughes, Reference Hughes2003; Gosarevski, Hughes, & Windybank, Reference Gosarevski, Hughes and Windybank2004; Lea & Curtin, Reference Lea and Curtin2011). A lack of land ownership by individual freehold title is seen as hindering long-term planning, preventing banks from offering loans to indigenous entrepreneurs, and as leading to arguments over land usage (Duncan, Reference Duncan2008). Customary land systems are thus seen by some as ‘anachronistic in modern economies’ (Jayaraman, Reference Jayaraman1999: 9). Hence;

…within the island Pacific there is little sign that culture, in whatever form, is seen as a resource but much more that it is seen as a brake on hopeful structures of development. (Curry, Koczberski, & Connell, Reference Curry, Koczberski and Connell2012: 122)

However, a number of dissenting voices have emerged to show that culture facilitates effective businesses on customary land (Fingleton, Reference Fingleton2004; Huffer & Qalo, Reference Huffer and Qalo2004; Bourke, Reference Bourke2005; Iati, Reference Iati2009; Allen, Reference Allen2012; Curry & Koczberski, Reference Curry and Koczberski2012; McCormack & Barclay, Reference McCormack and Barclay2013). There is now growing recognition – even from the World Banks and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations – that customary tenure can be more flexible and adaptable than previously assumed, and valuable for achieving a variety of development purposes (Fingleton, Reference Fingleton2004; National Land Development Taskforce, 2007; Ward & Kingdon, Reference Ward and Kingdon2007; AusAid, 2008). Culturally embedded alternative economic development approaches have strong implications for development policy and donor communities who are keen to support strategies that ‘enable commercial development on customary land while at the same time maintaining and protecting customary group ownership’ (Allen, Reference Allen2012: 300).

Research has shown that long-term relationships between partners are a key element of good Pacific business models (Gilbert, Rickards-Rees, Spicer, & Coates, Reference Gilbert, Rickards-Rees, Spicer and Coates2013). The relationships that adhere around and facilitate business engagements with customary land – be they with donors, government, churches, Non-Government Organisations (NGOs) or other private sector entities – and how they embody and express local cultural values, are crucial in the success of businesses of people of the Pacific. Ties to the land shape the nature of, and power within, the different relationships through which such economic engagements are developed and flourish. Research on economic enterprises in the agricultural sector in the Pacific has found, for example, strong collaborative relationships between the enterprise and its producers was of prime importance in achieving good development outcomes for communities (Coates, Clark, & Skeates, Reference Coates, Clark and Skeates2010).

People of the Pacific have been involved in a diverse range of businesses based around customary land that are associated with agriculture, tourism, fisheries and forestry (Ward & Kingdon, Reference Ward and Kingdon2007; Lea, Reference Lea2009; Gibson, Reference Gibson2012; Garnevska, Joseph, & Kingi, Reference Garnevska, Joseph and Kingi2014). For many emerging entrepreneurs in the Pacific, customary land is their greatest asset upon which they can build a business, whether they are planning an ecotourism enterprise in the rainforest, a plantation producing coffee or adding value through making cosmetics out of virgin coconut oil produced on customary land. However, that land is never perceived only as an economic asset to them; if they use it for a business, they must do so in ways which respectfully contribute to the wider society. Importantly, it is entrepreneurs, small businesses and sometimes NGOs, rather than foreign direct investment, that play a crucial role in driving much of this economic development (Coates, Clark, & Skeates, Reference Coates, Clark and Skeates2010). Further, successful productive enterprises in the Pacific are often organised around individuals, families and kin networks, with flow-on benefits to communities through gift-giving, reciprocity and financial support for communal activities (Cahn, Reference Cahn2008; Curry & Koczberski, Reference Curry and Koczberski2012). Family systems can be used, particularly by women, to encourage and enhance business success; beach fale tourism in Samoa provides a good example (Scheyvens, Reference Scheyvens2006). In addition, farmers in Fiji have been able to form successful collective enterprises by developing management groups that separate farm assets and income from village social obligations, whilst still being seen to contribute to the communal capital of the village (Duncan, Reference Duncan2008).

MEASURING SUCCESS OF INDIGENOUS BUSINESSES

The discussion thus far has demonstrated that culture informs Pacific Island entrepreneurs’ business goals and their business practices on customary land. When seeking to measure success or effectiveness of indigenous businesses on customary land, it is therefore vital to use tools which accommodate the unique approaches and socio-cultural goals of these businesses; using only financial measures of success fails to capture the value of these businesses. Entrepreneurial success in the Pacific, as shown above, is likely to be associated with the ability to meet traditional obligations and to maintain close ties with extended family, wantoks and clans (including utilising their support).

We have thus developed a tool (see Table 1 and Figure 1) which identifies factors that contribute to the sustainability of indigenous businesses operating on customary land in the Pacific. This tool is particularly inspired by Paul James’ model of ‘circles of sustainability’, which he applied to urban settings (James, Reference James2015). His circle has four domains (economics, ecology, politics and culture) whereas ours has three (socio-cultural, economic, environmental). Fundamentally, both James’ and our model operate on the premise that it is useful to provide a visual representation of the extent to which various dimensions of sustainability have been achieved in a particular context.

Figure 1 Indigenous business X: socio-cultural, economic and environmental sustainability

Table 1 Indicators of sustainability in Pacific Island businesses on customary landFootnote a

Note.

a Readers are encouraged to contact the authors if they would like more detail regarding the indicators that were developed.

In developing indicators to assess the sustainability of indigenous businesses operating on customary land in the Pacific, we drew from a wide body of literature as well as the collective expertise of the authors, one of whom is Fijian (Meo-Sewabu) and three of whom have many years of experience doing research in and with people from the Pacific (Meo-Sewabu, Scheyvens and Banks). This led us to develop the subcategories and indicators shown in Table 1, which provides a simplified version of the table we are utilising in our research to identify how various indigenous businesses on customary land fare in terms of three aspects of sustainability; we acknowledge, however, that in some cases there is overlap for example with socio-cultural and economic indicators. Note that the indicators in this table might also be modified post fieldwork in response to what we find from applying the tool in our pilot studies. As it will become clear, culture is embedded within each measure of the economic, environmental and socio-cultural spheres of business operations.

PROCESS FOR APPLYING THESE INDICATORS

Conducting this research in the Pacific meant that it was appropriate to utilise a novel combination of the Vanua Research Framework and the Tali magimagi research framework. The latter weaves together culturally appropriate and ethical research practices (Meo-Sewabu, Reference Meo-Sewabu2015), while Vanua research is grounded in indigenous values which ‘…supports and affirms existing protocols of relationships, ceremony, and knowledge acquisition. It ensures that the research benefits the vanua…’ (Nabobo-Baba, Reference Nabobo-Baba2006: 25). This meant that a number of cultural protocols that had to be adhered to when entering the research field. For Fiji, this included making initial contacts through members of our advisory group, addressing the participants in the Fijian language, and discussing commonalities and points of connection to the vanua before discussing the purpose of the actual research. Later testing of our business sustainability tool in Samoa and Papua New Guinea will be guided by the same principles.

An example of how we applied the indicators from our tool in a culturally appropriate way during pretesting was in relation to our questions. Initially there was a set of pre-prepared questions that were to be asked in sequence but in following the Vanua research framework it was culturally appropriate to use talanoa (story-telling or conversation), allowing the conversations to flow rather than asking people to answer questions verbatim (Vaioleti, Reference Vaioleti2006). Talanoa enables an openness to what is being discussed and occurs more naturally allowing the respondent to agree or disagree, share their stories, as well as openly discuss other issues relating to the research (Otsuka, Reference Otsuka2005; Nabobo-Baba, Reference Nabobo-Baba2006; Vaioleti, Reference Vaioleti2006). Thus rather than rushing people, there was time for intricate details of their stories to be shared, which seemed to allow the participants to speak more freely about their business. In addition, the questions were changed in terms of sequence of what was being asked. For example, it seemed more culturally appropriate to begin by asking participants about the history of their business – how and when it had started. Questions were then amended accordingly with probing questions added to ensure the talanoa flowed. Some financial questions proved to be difficult for participants. Asking about profit was a sensitive matter and therefore it was left up to the discretion of the respondent whether they wished to share such information. In future, we will just ask if they are happy with the profits or not. Employment was a touchy subject for one respondent as the turnover rate was high as a result of workers becoming qualified and preferring to work elsewhere. In such cases, our research team will need to reflect on whether there are other ways in which we can investigate issues where it is not appropriate to ask for a direct answer from the respondent being interviewed. Interestingly, questions on environmental criteria were also somewhat awkward to ask during the pretesting as it felt like the researcher was interrogating how the business managed waste. These questions were amended and it is suggested that it might be more appropriate to explore environmental aspects of the business via talanoa when doing a site visit. On the other hand, questions included in the socio-cultural criteria were easy to discuss in talanoa form as this naturally flowed on from how businesses were contributing to the community as well as what makes them successful.

On reflection, the process we used during pretesting of the business sustainability tool was largely appropriate, especially as we had flexibility to change our approach in response to the environment. Adhering to the Vanua Research Framework showed our respect for our research participants. For example, at the end of the talanoa the interviewees were given a koha (Māori term for gift or offering) to thank them for their time; they were also told that they might be consulted in future if we were considering their business for the more detailed case studies that will be carried out in phase 2 of our research project. One thing we might do during the remainder of the research project is to work with a ‘cultural discernment group’ when doing field research on indigenous businesses. A cultural discernment group includes people with intimate cultural knowledge who can guide researchers to ensure the research occurs appropriately within cultural boundaries (Meo-Sewabu, Reference Meo-Sewabu2014). This could include advising on appropriate ways of asking questions, or on how to reframe questions so that they are not too confrontational.

RESULTS OF THE PRETESTING

Meo-Sewabu piloted the tool in two indigenous businesses in Fiji in February 2017. A representation of the resultant circle of sustainability for one of these businesses is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 provides a snapshot of the information we collected on one of two Fijian businesses run by indigenous entrepreneurs, which were part of our pretesting. The circles of sustainability tool thus provides a quick visual means of analysing the extent to which different criteria associated with sustainable practice of indigenous business are addressed by the particular business. In this case, Indigenous Business X is very strong in terms of its contributions to socio-cultural well-being of the community in which it is located. It could also be regarded as scoring very well on economic criteria overall: even though the profits were not seen to be very strong, and the multiplier effects were not extensive, it scored well in this category because the business was indigenous-owned and managed (as opposed to many businesses on customary land in Fiji which, via lease arrangements, are owned and operated by foreigners), it had been established and running effectively for a relatively long period of time, and it employed people solely from the local community. This business did not rate so strongly on environmental criteria; a manager admitted they had paid little attention to date to environmental aspects of the business. In the face of the socio-cultural, economic and cultural aspects of success, the environmental aspects are not currently as significant for this business. This does not however, mean that the environment should not figure in calculations of indigenous business success and sustainability, because as we have argued above in the discussion of vanua, the ‘environment’ is closely tied to other aspects of the land and society in the Pacific.

CONCLUSION

This article has shown that land is a key social, cultural and economic resource for indigenous business in the Pacific, and that there is particular promise in considering customary land as a basis for indigenous entrepreneurship and business success. Land, and the complex web of social, cultural, political and economic relationships that are woven through it in Pacific societies, is both integral to the identities of diverse groups of people in the Pacific and a central resource for their development. When examining the economic potential of that land, therefore, it would be remiss not to acknowledge the socio-cultural and environmental significance of the land as well.

The significance of these other elements is clear in the way in which Pacific entrepreneurs run their businesses. We have discussed how, rather than focussing on individual gain and maximising short-term financial profits, many Pacific businesses take a more collective approach to their endeavours, balancing customs with contemporary business practices. While doing so can lead to greater risks for the business in some ways, it can strengthen it in others. Thus when a business honours communal obligations this can strengthen social capital, generate goodwill towards their products and services, and develop business resilience based on the resulting reciprocal obligations. Overall, this can contribute to longevity and sustainability of the business. Thus our understanding of the potential of Pacific businesses needs to be based on an awareness of both the constraints faced by these businesses and the positive aspects of being a socially-connected and culturally embedded business.

As noted at the outset, despite the high proportion of land under customary forms of tenure across the region, there has been very little work that directly examines the significance of customary land as a social and cultural resource for indigenous business in the Pacific. This reflects the limited framing of business success among indigenous entrepreneurs in the Pacific, where external and donor criteria focus on financial viability. We have thus asserted that when measuring the sustainability of indigenous businesses it is very important to consider socio-cultural, economic and environmental factors, something that standard evaluations of indigenous entrepreneurial business success have failed to do. The tool for measuring sustainability of businesses on customary land in the Pacific that we developed (Table 1 and Figure 1) is thus based on a broad range of criteria. Our argument is that culturally meaningful tools such as this are essential if the sustainability of indigenous businesses is to be measured in terms that make sense to Pacific communities. We will continue to test this tool in our research, and would welcome its application by other researchers, particularly those interested in examining indigenous entrepreneurship and businesses on customary land.