In May 2018, a grainy cell phone video began making the rounds online, eventually gracing the front cover of the New York Daily News. In the video,Footnote 1 a visibly angry man brandishes a cell phone and confronts a Spanish-speaking worker in a Midtown Manhattan restaurant with the words, ‘My guess is [your co-workers are] not documented, so my next call is to ICE to have each one of them kicked out of my country…I pay for their welfare, I pay for their ability to be here – the least they can do is speak English.’ In 2018, this was no idle threat – under the first year of the Trump administration, arrests of unauthorized immigrants without a criminal record more than tripled compared to the previous year (Leonard Reference Leonard2018). Over the same period, reports of employers threatening to call immigration authorities on workers more than quadrupled (Khouri Reference Khouri2018).

What motivates people to report immigrants to Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE)? Is it driven by situational factors such as encountering a suspected unauthorized immigrant, or do media narratives play a role in encouraging this behaviour? Previous studies have found that anti-immigrant narratives can influence behaviour, inducing information-seeking behaviour about immigration (Gadarian and Albertson Reference Gadarian and Albertson2014) as well as an interest in contacting elected officials with anti-immigrant messages (Brader, Valentino, and Suhay Reference Brader, Valentino and Suhay2008; Hainmueller, Hiscox, and Margalit Reference Hainmueller, Hiscox and Margalit2015). The framing of the immigration debate has serious policy implications, with more sympathetic portrayals reducing support for deportation (Haynes, Merolla, and Ramakrishnan Reference Haynes, Merolla and Ramakrishnan2016; Jones and Martin Reference Jones and Martin2017; Knoll, Redlawsk, and Sanborn Reference Knoll, Redlawsk and Sanborn2011; Merolla, Ramakrishnan, and Haynes Reference Merolla, Ramakrishnan and Haynes2013b). Anti-immigrant narratives play a broad role in US politics, as narratives about immigrant crime and welfare use (‘immigrant threat narrative’) shape policy preferences about criminal justice and the welfare state (Abrajano and Hajnal Reference Abrajano and Hajnal2017).

Reporting immigrants to ICE is a modern form of denunciation, a behaviour which involves reporting alleged deviant behaviour by others to the government. This behaviour is largely studied in historical and comparative contexts, such as Nazi Germany or the Soviet Union (Fitzpatrick Reference Fitzpatrick1996; Fitzpatrick, and Gellately Reference Fitzpatrick and Gellately1996; Joshi Reference Joshi2003), though some authors have noted the role of denunciation in US anti-terrorism policy (Bergemann Reference Bergemann2019). In democratic societies, individuals who use denunciation are motivated by a desire to remove members of threatening out-groups within their community (Bergemann Reference Bergemann2019). In the case of unauthorized immigration into the United States, ideology and inter-group conflict may play important roles in encouraging denunciation. Implicit anti-Latino attitudes increase political support for deportation (Pérez Reference Pérez2016), as does Republican party identification (Jones and Martin Reference Jones and Martin2017). Still, denunciation (reporting someone to ICE) is qualitatively distinct from merely holding anti-immigrant or pro-deportation attitudes. Many Americans who have pro-deportation attitudes are not interested in reporting anyone to ICE, and the factors that encourage denunciation of unauthorized immigrants may be different from those that lead to pro-deportation attitudes. While we do not study reporting behaviours directly, we do study a vital step in the process: web searches for how to report.

Can anti-immigrant media narratives trigger interest in immigrant denunciation among American viewers? To address this question, we combine a novel dataset of Bing and Google searches for anti-immigrant queries, including a comprehensive set of queries about how to report immigrants to ICE, with automated text analysis of TV transcripts from CNN, MSNBC, and Fox News from 2014 to 2019. We can identify two key anti-immigrant topics within the transcripts: immigrants committing crimes and immigrant usage of social benefits. We look at shifts in these topics over time and leverage this temporal variation to measure the effects of the immigrant threat narrative on immigrant-reporting searches. We also examine the role of anger, fear, disgust, and sadness language cues in the transcripts to understand their effect on reporting interest. Finally, we use hourly time-stamped search data to examine the effects of President Trump and President Obama's speeches about immigration on reporting searches to isolate the effect of anti-immigrant broadcasts.

We find that, after the 2016 election, news coverage of the immigrant threat narrative became more prevalent, especially on Fox News. We identify a strong correlation between daily coverage of immigrant crime topics and immigrant-reporting searches. Fear cues in news transcripts significantly and positively affected immigrant-reporting searches, distinct from the effect of the immigrant threat narrative. We also find that all three categories of the anti-immigrant searches we measure, including reporting searches, dramatically increased during the broadcasts of President Trump's speeches about immigration. We do not find similar effects in Obama's televised addresses. These findings suggest that in the wake of the 2016 election, anti-immigrant media coverage increased, which may have resulted in a significant uptick in interest in immigrant denunciation.

The rest of the article is organized as follows. The next section describes the theoretical perspectives that motivate this study. The third section presents our hypotheses about conditions that prompt interest in the reporting of immigrants. The fourth section discusses our data sources and delineates our analysis strategy. The fifth section demonstrates the rise of anti-immigrant rhetoric via television news coverage after the 2016 election. The sixth section documents the rise in anti-immigrant searches after the 2016 election and demonstrates the strong association between daily anti-immigrant searches and news segments about immigration. The seventh section uses hourly search data to isolate the effect of anti-immigrant media broadcasts, specifically Donald Trump's televised speeches on anti-immigrant searches. It compares these to the effects of the televised speeches by Barack Obama. The final section describes the implications of our findings.

Media Messages and Anti-Immigrant Beliefs and Behaviours: What We Know and Do Not Know

Scholars have identified several effects of the media on public opinion (Strömberg Reference Strömberg2015). The media has a well-documented agenda-setting impact on which political issues are seen as most important by voters (Iyengar and Kinder Reference Iyengar and Kinder2010). However, mass media can play a role beyond that of agenda setting – activating public opinion. When a person's opinion on an issue is activated, their opinion about this issue is both ‘salient in the mind and impels [them] to political action’ (Lee Reference Lee2002). Through activating public opinion, mass media can compel the public to engage in a variety of behaviours that influence the political process. These include expressive behaviours such as tweeting about an issue (King, Schneer, and White Reference King, Schneer and White2017) or communicating with elected officials. Activated public opinion has played a key role in shaping the politics of race and ethnicity in the US. Lee (Reference Lee2002) described the role of civil rights activists in activating Northern whites' public opinion, which, he argues, led to the passage of civil rights legislation in the 1960s.

Media coverage is also an extremely important propagator of presidential cues. Americans tend to follow cues from ‘copartisan’ political figures when forming their policy preferences (Achen and Bartels Reference Achen and Bartels2017; Layman and Carsey Reference Layman and Carsey2002; Lenz Reference Lenz2013; Levendusky Reference Levendusky2009). While presidents communicate with their supporters through email and, more recently, social media, the press plays an important role in mediating these cues (Dalton, Beck, and Huckfeldt Reference Dalton, Beck and Huckfeldt1998), amplifying some while diminishing others. This role is especially notable in the scenario during the Trump administration, with media organizations vigorously debating their role in fact-checking inaccurate claims.Footnote 2 The debate over amplifying Trump's cues was notable in media discussions over whether to broadcast his 2019 Oval Office address on immigration live on the air.

Negative media portrayals of immigrants are common (Alamillo, Haynes, and Madrid Reference Alamillo, Haynes and Madrid2019; Kim et al. Reference Kim2011). Between 2000 and 2010, the media regularly showed immigrant arrests and detentions, implying their criminality (Farris and Silber Mohamed). Immigrants are disproportionately portrayed as male and Latino (Silber Mohamed and Farris Reference Silber Mohamed and Farris2019), invoking the ‘Latino threat’ narrative, which emphasizes criminality and a lack of assimilation as common traits of immigrants from Latin America (Chavez Reference Chavez2013). Media coverage of immigration has been shown to have a significant impact on anti-immigrant sentiment (Benesch et al. Reference Benesch2019) as well as broader impacts on white Americans' support for more punitive criminal justice and welfare policies (Abrajano and Hajnal Reference Abrajano and Hajnal2017).

Several studies have explicitly focused on factors that influence attitudes toward deportation from the US. Pérez (Reference Pérez2016) highlights the role of implicit anti-Latino attitudes in decisions about whether or not to deport a specific hypothetical immigrant. Haynes, Merolla, and Ramakrishnan (Reference Haynes, Merolla and Ramakrishnan2016) explore the role of various pro- and anti-deportation arguments, such as the rule of law or the cultural impact of immigration in support of deportation. Several papers have looked at the use of specific labels such as ‘undocumented’ or ‘illegal’ (Knoll, Redlawsk, and Sanborn Reference Knoll, Redlawsk and Sanborn2011; Merolla, Ramakrishnan, and Haynes Reference Merolla, Ramakrishnan and Haynes2013b) and the role of campaign cues on immigration attitudes (Jones and Martin Reference Jones and Martin2017).

A number of studies have focused on the effects of rhetoric and framing on anti-immigration behaviours and attitudes (Haynes, Merolla, and Ramakrishnan Reference Haynes, Merolla and Ramakrishnan2016; Merolla, Ramakrishnan, and Haynes Reference Merolla, Ramakrishnan and Haynes2013b; Merolla et al. Reference Merolla2013a; Valentino, Brader, and Jardina Reference Valentino, Brader and Jardina2013). Several conclusions have emerged from this literature. First, stimuli that engage anxiety are the most effective at mobilizing political participation and information-seeking behaviour around immigration (Brader, Valentino, and Suhay Reference Brader, Valentino and Suhay2008; Gadarian and Albertson Reference Gadarian and Albertson2014). Fear cues have been shown to stimulate information-seeking behaviours in a variety of contexts beyond immigration (Brader Reference Brader2005; Brader Reference Brader2005). Second, frames emphasizing cultural threats from immigration are more effective at generating opposition to immigration than frames emphasizing native-born citizens' economic interests (Brader, Valentino, and Suhay Reference Brader, Valentino and Suhay2008; Hainmueller and Hopkins Reference Hainmueller and Hopkins2014; Haynes, Merolla, and Ramakrishnan Reference Haynes, Merolla and Ramakrishnan2016).

While this literature provides a rich background for understanding the relationship between xenophobic rhetoric, attitudes towards deportation, and anti-immigrant behaviours, several key areas remain under-explored.

First, most studies that look at anti-immigrant behaviours look at policy-relevant behaviours, such as contacting an elected representative (Brader, Valentino, and Suhay Reference Brader, Valentino and Suhay2008; Hainmueller, Hiscox, and Margalit Reference Hainmueller, Hiscox and Margalit2015; Merolla et al. Reference Merolla2013a), agreeing to learn more about the issue (Brader, Valentino, and Suhay Reference Brader, Valentino and Suhay2008; Gadarian and Albertson Reference Gadarian and Albertson2014), or voting on naturalization applications (Hainmueller and Hangartner Reference Hainmueller and Hangartner2013). These are all behaviours that exist within the democratic process in which citizens learn about issues, vote in elections, and attempt to influence their elected officials to support their preferred policies. However, not all media-influenced behaviours are so benign. Previous literature in the comparative context has found that media exposure can motivate violence against ethnic minorities, often by encouraging personal participation (Müller and Schwarz Reference Müller and Schwarz2019; Warren Reference Warren2015; Yanagizawa-Drott Reference Yanagizawa-Drott2014). While violent behaviours exist at the extreme end of the spectrum, there is still a wide range of extra-democratic behaviours intended to harm immigrants, from expressing anti-immigrant comments to employment discrimination to denunciation of immigrants or ICE. Understanding the role of media messages in triggering these behaviours in individuals is crucial to understanding the full spectrum of responses to xenophobic rhetoric. If xenophobic rhetoric merely encourages people to participate in the political system and express anti-immigrant opinions to government officials, in that case, it is far less dangerous than if it encourages people to take actions directly harmful to immigrants.

Second, many immigration and media studies use similar methodological approaches, which have some weaknesses in the case of studying anti-immigrant behaviours. Many studies that focus on anti-immigrant attitudes and behaviours rely on surveys to measure their main dependent variable of interest. While surveys allow for experimentation and provide researchers with precise control over the wording of questions, they can raise a variety of concerns, such as social desirability bias. While recent research has questioned the importance of social desirability in some domains (Blair, Coppock, and Moor Reference Blair, Coppock and Moor2020), anti-immigrant behaviour is a domain where it still retains significant power. Hainmueller and Hangartner (Reference Hainmueller and Hangartner2013) found that Swiss citizens voting in immigration referenda tended to exhibit strong social desirability effects; their votes were much more discriminatory on the basis of the immigrants' ethnic origins than their responses to comparable public opinion surveys.Footnote 3 Even studies that measure anti-immigrant behaviour in the US context (such as contacting an elected official) are embedded in an experimental environment, replicating these same social desirability effects.

While social desirability effects may limit the degree to which people are willing to engage in anti-immigrant behaviour in a research setting, these environments might generate a converse effect. Despite the prevalence of anti-immigrant rhetoric in popular media, only a small percentage of Americans choose to contact their elected representatives about immigration.Footnote 4 A laboratory setting, where participants are offered this choice, may overestimate the proportion of people who behave similarly outside an experiment. Likewise, a survey experiment where a participant is shown a prompt and asked whether or not they would be willing to deport the person described in the prompt is a very different situation from the same participant choosing to report someone to ICE outside of an experimental context. In the first setting, the respondent is provided with the ‘deport’ option by the experimenter and knows that their choice will not have any consequences. The second setting requires the person to organically search for how to report someone to ICE without prompting by an experimenter, knowing that if they choose to report, their report may have very serious consequences. A stimulus that encourages a meaningful proportion of respondents to select a ‘deport’ option in a lab may be insufficient to move the same respondents to take a step toward reporting someone to ICE. Americans get a specific dosage of anti-immigrant narratives through the media. Knowing whether or not these narratives are enough to generate interest in reporting immigrants to ICE outside of a research setting is key to understanding the effects of anti-immigrant rhetoric.

Denunciation of Immigrants As Political Behaviour

Why might people be interested in reporting a suspected unauthorized immigrant to ICE? While political scientists have studied denunciation in the context of counter-insurgency (Shaver et al. Reference Shaver2016; Wright et al. Reference Wright2017) and whistleblowing (Fiorin Reference Fiorin2023; Ting Reference Ting2008), most studies on denunciation outside of these specific contexts come from history literature. Using historical case studies, Bergemann (Reference Bergemann2019) provides a framework for considering the motives for denunciation in various contexts. While some regimes encourage denunciation through coercion, both explicit (torture) and implicit (providing benefits for those who denounce others), many other regimes operate their denunciation systems on an entirely voluntary basis. Under such systems, denouncers are often protected by a veil of anonymity, and while false denunciations are not punished, denouncers gain no material rewards from the government by denouncing. The United States has had a number of recent programmes encouraging denunciation, from the ‘If you see something, say something.’ anti-terrorism campaign to the Trump administration's recent Victims of Immigrant Crime Engagement hotline.

The most common impetus in a democratic society is what is termed a ‘pro-social’ denunciation (Bergemann Reference Bergemann2019). Under a pro-social denunciation, the denouncer believes the denounced person represents a genuine threat to society and removing that person will generate net good for many people. This contrasts with other forms of denunciation, where the motive may be financial gain or retaliation against an enemy. One key motivation that holds true across multiple denunciation contexts, including pro-social denunciation, is the desire to remove the denounced person to reap whatever gains were sought from the denunciation.

We argue that the media plays a key role in sparking interest in denunciations of suspected unauthorized immigrants to ICE in three different ways. First, the media provides important cues about elected officials' political positions. When an elected official explicitly supports negative sanctions against people engaged in undesirable behaviours, this can encourage would-be denouncers to report these behaviours. People are more likely to engage in political action when they believe that action will yield results – for example, turnout increases in close elections (Cancela and Geys Reference Cancela and Geys2016; Fraga and Hersh Reference Fraga and Hersh2010). This leads us to our first hypothesis:

H1: People will have more interest in reporting immigrants when they believe the government supports deportation.

Donald Trump engaged in extreme anti-immigrant rhetoric during his campaign, with promises to create a deportation force specifically designed to remove unauthorized immigrants from the country. We expect that people who are interested in denouncing immigrants to ICE will be more likely to do so after Trump takes office, with searches for reporting immigrants increasing immediately after his inauguration. The increase in searches should remain significant even after accounting for time trends and the amount of anti-immigrant media coverage. We also expect that when the Trump administration receives media coverage for anti-immigrant rhetoric or policies, we will see an uptick in reporting searches. However, we do not expect a discontinuity in reporting searches immediately after the 2016 election, nor do we expect media coverage of candidate Trump's anti-immigrant rhetoric to generate more reporting searches. Neither candidate Trump nor president-elect Trump had the power to change immigration policy before his inauguration, so his anti-immigrant positions should not increase interest in reporting.

Second, we argue that due to the significant and consistent effect of negative out-group media coverage on negative attitudes toward out-group members (Das et al. Reference Das2009), mass media coverage is a key driver of pro-social denunciation interest. Unlike in other denunciation contexts, pro-social denouncers focus on denouncing out-group members they find threatening (Bergemann Reference Bergemann2019). Our second hypothesis focuses on the role of cultural threat, specifically the immigrant threat narrative. Previous literature has shown that cultural threat poses a greater role in opposition to immigration than economic competition (Hainmueller and Hopkins Reference Hainmueller and Hopkins2014). In the US, the immigrant threat narrative largely focuses on concerns about immigrant crime and the utilization of government benefits. As such, media coverage that invokes this narrative is most likely to generate searches for reporting immigrants, even after controlling for the total amount of coverage about immigration.

H2: People will have more interest in reporting immigrants when exposed to rhetoric about immigrants committing crimes and immigrant receipt of government benefits.

Our final hypothesis focuses on fear cues in reporting searches. A number of studies focus on the role of emotion in triggering anti-immigrant responses. Anxiety about rising immigration levels has been identified as a key emotion that triggers both information-seeking and politically participatory behaviours in the context of immigration (Brader, Valentino, and Suhay Reference Brader, Valentino and Suhay2008; Gadarian and Albertson Reference Gadarian and Albertson2014). While some studies find that emotion is the causal mechanism by which news coverage generates anti-immigrant behaviours, we study the two hypotheses separately to determine whether emotional cues alone can trigger interest in denunciation.

H3: People will have more interest in reporting immigrants when exposed to fear cues about immigrants.

These three hypotheses demonstrate how a number of different media cues can trigger interest in the denunciation of immigrants to ICE. First, the media can provide cues about the current government's position on deportations and, thus, the likelihood of removing the threatening denounced person. Second, the media can exacerbate out-group threats against immigrants through the invocation of the ‘immigrant threat narrative’ and thus generate motivations for their removal. Finally, the media can elicit fear-based emotional cues, which have been shown to be effective in spurring anti-immigrant political participation.

Empirical Approach

This paper uses various data sources to study the effects of media messaging on public interest in anti-immigrant denunciations. The main outcome variable of interest is web search behaviour, measured by Bing and Google searches.Footnote 5 Within our web search data, we look at searches for reporting immigrants as our main variable of interest, with two secondary variables that measure search interest in immigrant crime and immigrant welfare use. Table 1 summarizes the data sources and their availability.

Table 1. Data summary

1 News transcript data was available for only 01/15–08/19 for MSNBC.

We use two approaches to measure the effect of media coverage on anti-immigrant searches. In the first approach, we look at daily Google and Bing searches for anti-immigrant keywords and compare the volume of these searches with the amount of media coverage on anti-immigrant topics. This approach tests whether there is an association between anti-immigrant media coverage and anti-immigrant search volume. Our second approach uses time-stamped searches during Trump and Obama's televised speeches to determine whether there was a spike in anti-immigrant web searches during a widely-watched anti-immigrant media broadcast.

Why Reporting Searches Matter

Our measure for interest in reporting is web searches for queries such as ‘how to report an immigrant to ICE’ and ‘report illegal immigrants anonymously’. The next section describes our process for selecting these queries in detail. This section outlines three reasons why such queries are a useful measure of anti-immigrant attitudes and behaviours.

First, at least some searches for ‘how to report an immigrant’ will likely result in an actual denunciation. While web searches are a form of information-seeking behaviour, not all information-seeking behaviours are created equal. Prior studies of immigration that examine information-seeking behaviour in the immigration context examine the willingness to read a news article about immigration (Gadarian and Albertson Reference Gadarian and Albertson2014) or to sign up to receive more information about immigration from an outside group (Brader, Valentino, and Suhay Reference Brader, Valentino and Suhay2008). On the other hand, searches for ‘how to report an immigrant’ fall into a different category of information-seeking behaviour, referred to in marketing literature as a ‘conversion funnel’. Jansen and Schuster (Reference Jansen and Schuster2011) find that search engine users interested in purchasing a specific item, such as a computer, go through various search terms that become increasingly more specific as they move through the funnel. A substantial fraction of searchers in each phase of the funnel move on to the next, with some ultimately choosing to purchase the product. Searches for ‘how to report an immigrant’ are fairly late in the conversion funnel, as searches have identified a problem (in this case, immigrants) and are actively searching for a solution to the identified problem. Even if searchers do not ultimately report an immigrant to ICE immediately as a result of this search, they are now more familiar with the process and can report someone later or pass the information along to someone else who will make a report. Knowing how to report may also empower people to make threats to report suspected unauthorized immigrants to ICE, even if they do not follow through.

While the conversion funnel model was developed to describe online purchase behaviour, web searches are a precise predictor of offline behaviour in a wide variety of political and non-political contexts.Footnote 6 As such, when an event results in a clear spike in web searches for ‘how to report an immigrant to ICE’, it is highly likely to be followed by a spike in actual reports to ICE.

Second, even searches that do not result in a report to ICE still signal support for the deportation of unauthorized immigrants. Many of these searches, including four out of the top ten most common queries, are explicitly interested in reporting immigrants to ICE ‘anonymously’, suggesting that the searcher is concerned about suffering retaliation or reputational harm due to their report. This level of specificity in searches is unlikely to represent an idle curiosity about the workings of the US immigration system. We find that media events that result in spikes for reporting searches do not explicitly ask viewers to report anyone to ICE. Instead, viewers organically generate searches for how to report immigrants. This suggests that they not only support deportations but see them as a preferred policy solution and are interested in personally participating. This is a meaningful set of attitudes, even if they do not translate directly into reporting behaviours.

Finally, the elicitation of extreme anti-immigrant attitudes and a willingness to personally participate in behaviours that harm immigrants can lead to other, non-reporting, anti-immigrant behaviours. The same attitudes that lead to a desire to harm or remove immigrants via denunciation can manifest in other anti-immigrant behaviours, such as threats and discrimination. Even if people do not ultimately report anyone to ICE as a result of their search, the search itself is a strong indicator of their interest in engaging in anti-immigrant behaviours up to and including violence.

In addition to our searches measuring interest in reporting immigrants to ICE, we look at a secondary set of searches measuring interest in crimes committed by immigrants and immigrant welfare usage. While these searches do not necessarily represent anti-immigrant attitudes, they show an interest in and engagement with anti-immigrant narratives. We expect immigrant/crime and immigrant/welfare searches to correlate with reporting searches, as we predict that the same set of anti-immigrant messages influences all three search categories.

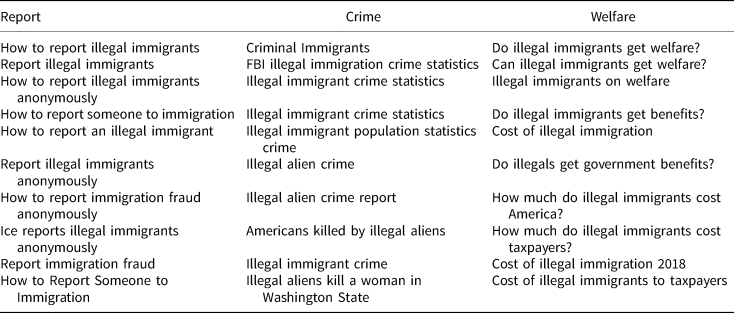

Measuring Real-Time Interest Through Search Data

We turn to web search data to measure reporting interest and search interest in immigrant crime and welfare usage. We broadly refer to this set of searches as ‘anti-immigrant searches’ throughout the paper. Specifically, we look at Google and Bing for searches about immigration and crime, immigration and welfare, and information about reporting immigrants to ICE. These searches contain at least one immigration term and one keyword associated with the search category (for example, ‘report’). Please see the appendix for a detailed explanation of how search terms were selected. Table 2 shows the top ten Bing searches for each topic.

Table 2. Top 10 Bing searches for each immigration topic

Notes: The table represents the top ten searches for each search category in the US. The searches were overwhelmingly negative in tone towards immigrants and overwhelmingly focused on unauthorized immigrants.

To measure Google search volume, we used Google Trends data. A downside of this data, in contrast to Bing data, is that it limits the number of terms that can be used and does not allow the manual removal of terms that, while matching the keywords, are not related to immigration. Despite these limitations, the Google Trends results consistently replicate the Bing results.

We aggregate these searches using two different intervals of time – the hourly level and the daily level. Hourly-level searches measure the effects of presidential speeches on anti-immigrant searches, while daily-level searches are used to understand the broader relationship between anti-immigrant searches and media coverage.

Estimating News Content Using Structural Topic Models

To measure immigration news coverage over time, we rely on MSNBC, Fox News, and CNN transcripts from 2014 to 2019. Time-stamped transcripts were downloaded from the Internet Archive. While Fox and CNN transcripts were available for 2014–2019, MSNBC was only available for 2015–2019.

News transcripts are used as a proxy for media coverage of specific aspects of the immigration issue. When we see an increase in coverage of immigration and crime in the transcripts, this suggests that multiple print, online, and TV news outlets also increased their coverage of this issue. The results in this paper do not necessarily reflect TV alone but news media coverage collectively, of which TV is by far the dominant mode of public consumption (Allen et al. Reference Allen2020). Cable news, in particular, allows for the analysis of a wide range of perspectives that shape broader national news agendas.

To measure changes in media coverage of immigrant-related issues before and after the 2016 election, we use a structural topic model (Wang, Zhang, and Zhai Reference Wang, Zhang and Zhai2011) to estimate the prevalence of various immigrant-related topics in CNN, MSNBC, and Fox News transcripts.

Structural topic models are a form of semi-automated text analysis that allows document covariates to be included when estimating topical prevalence or content (Roberts et al. Reference Roberts2014). Topic models assign each document a topic proportion for each topic, which means that a document can (and often does) belong to multiple topics (for example, 0.1 topic A, 0.2 topic B, 0 topic C). The model generates a wide variety of topics relating to immigration.Footnote 7 In the appendix, Table A1 shows the full results of the topic model.

We focus on three topics from the model: Topic 1 and Topic 3, which are classified as crime topics, and Topic 13, which is classified as a welfare topic. Figure 1 shows the documents most representative of each topic, all of which represent an anti-immigrant point of view. Furthermore, as further demonstrated in the results section, these topics are significantly more likely to be covered by Fox News than by MSNBC or CNN, further suggesting that these news segments depict immigrants in a negative light.

Figure 1. Immigrant crime and welfare topics.

Notes: These documents have the highest association with Topics 1, 3, and 13a.

aThese documents were selected using the FindThoughts() function of the STM package, which uses the posterior probability of a topic given a document to return the documents most representative of a topic. The pictured documents are the top documents returned for each topic.

To measure emotion in news transcripts and presidential speeches, we use the sentimentr R package to measure the presence of four negative emotions, anger, fear, disgust, and sadness,Footnote 8 in each immigration segment. Cable news often uses visual affective cues in concert with emotional language, and language alone can prove a potent emotional cue even in the absence of additional imagery (Lindquist Reference Lindquist2017; Utych Reference Utych2018). While this methodology is not a perfect measure of the emotions induced by media coverage in viewers, it serves as a reasonable heuristic of the emotional cues sent by the media coverage. In general, Fox News tended to have more negative emotional cues around immigration than MSNBC or CNN, and negative cues increased during and after the 2016 election.Footnote 9

Measuring Media Effects Using Presidential Speeches

We look at hourly searches during presidential speeches to determine whether changes in anti-immigrant searches can be directly attributed to anti-immigrant broadcasts. We compare searches made during a speech to searches precisely one week before and one week after the speech. Searches tend to have significant day-of-the-week effects. Searches one week before or one week after a speech are a better control group than searches one day before or one day after, as people search differently on weekdays than at weekends.

Televised presidential addresses are an ideal test of the effects of anti-immigrant broadcasts on anti-immigrant search behaviour. Each address is a major media event with an audience of tens of millions of Americans watching the speech live. Unlike nightly news broadcasts, there are no competing political media broadcasts of a similar magnitude during a presidential address, so spikes in anti-immigrant search terms used during this time can be attributed to the address. Finally, political media events of the same magnitude as televised presidential addresses are rare, so comparisons to search patterns at the same time one week before or after the speech are unlikely to be confounded by a different political media event. Using the hourly Google Trends data, which is available for the prior five years, we examine searches during Trump and Obama's State of the Union (SOTA) addresses in 2015–2019, as well as Trump's 2019 Oval Office address about immigration.Footnote 10 These speeches are all heavily televised events that draw tens of millions of viewers.

The comparison with Obama's speeches is useful because both presidents mentioned immigration in their SOTU speeches but from very different perspectives. Trump's comments on immigration during his speeches were much more negative and focused on immigrant criminality and welfare dependence. By contrast, Obama's mentions of immigrants tended to be positive. This allows us to verify that anti-immigrant search spikes can be attributed to anti-immigrant messages rather than positive messages about immigrants.

It is important to note that none of the presidential speeches studied exhorted Americans to report anyone to ICE. Furthermore, we find no evidence that media broadcasts about immigration explicitly direct people to denounce immigrants to ICE. If media broadcasts affect interest in denunciation, it is not because viewers follow directions expressly given by the media. Instead, they are responding to cues about immigrants and beliefs about their threat to the US.

Results: Anti-Immigrant Media Messages Became More Prevalent After 2016

After the 2016 presidential election, media coverage of immigration increased, and the content became more negative towards immigrants. Figure 2 plots the total daily duration of immigration news segments across three periods and three cable news channels. While there was little change in the daily duration of immigration coverage between the pre-campaign and campaign periods, there was a significant increase after the inauguration, especially on Fox News. While there was a modest post-inauguration increase in immigration coverage on CNN and MSNBC, Fox News' average monthly number of immigration segments nearly doubled after the inauguration, from 303.5 to 545.2. This suggests that a substantial portion, if not all, of the news effects we measure can be attributed to stories originating from Fox and other forms of right-wing media, many of which are highly anti-immigrant.

Figure 2. Immigration news segments.

Notes: There was a small increase in the monthly number of immigration segments aired by CNN and MSNBC after Trump's inauguration, while Fox News nearly doubled its immigration coverage.

In addition to increases in the volume of coverage, the content of immigration news coverage also shifted.Footnote 11 Fox News, which had the highest proportion of immigrant crime coverage of the three channels in our dataset, both increased its volume of immigration coverage and devoted more of its immigration coverage to crime. Figure 3 presents the proportion of daily coverage devoted to immigration and crime and immigration and welfare for each of the three channels.Footnote 12

Figure 3. Immigration news segments by topic.

Notes: The overall amount of immigration crime and immigration welfare coverage increased substantially in the post-inauguration period, especially on Fox News. Coverage of a topic is defined as the sum of the crime/welfare topic proportion across all documents per month for that channel.

In sum, cable news coverage became markedly more focused on immigrant crime and welfare during the 2016 campaign and especially after Trump's inauguration. Cable news coverage can be considered a proxy for media coverage more broadly, and the nature of this shift suggests that the public had much greater exposure to messages about immigrant crime and welfare dependency after the 2016 presidential campaign. In the next section, we examine web search patterns around immigration during the post-inauguration period and show their relationship to media coverage.

Anti-Immigrant Searches Closely Track Media Coverage

Echoing the discontinuity in media coverage shown in Figs 2 and 3, there was a clear discontinuity in anti-immigrant search rates after the 2017 inauguration of Donald Trump. Figure 4 plots the proportion of Bing and Google searches for the three sets of immigration terms during the Trump, Obama, and Bush administrations.Footnote 13 For each set of terms, searches were substantially increased in the days after Trump's inauguration. Furthermore, in addition to the immediate post-inauguration spike in searches, the baseline level of anti-immigrant searches either remained constant or increased throughout the Trump administration. This difference is especially pronounced for reporting searches where a sharp discontinuity at the inauguration was followed by relatively little change. On the other hand, we see no discontinuity after the 2016 election in either the Bing or the Google reporting searches.

Figure 4. Immigration searches by administration.

Notes: For all three sets of anti-immigrant terms, searches increased on Bing and Google after Trump's inauguration speech. There was also a spike in all three sets of terms in the months immediately after the inauguration. For the Bing data, the Y-axis is daily searches for the immigration terms as a percentage of daily Bing searches on a log10 scale, and each data point represents one day. For the Google data, the Y-axis is Google Trends' ‘Interest over Time’ measure, and each data point represents one month.

The increase in immigration searches after Trump's inauguration was non-trivial and highly consistent across both the Google and Bing data. Compared with the Obama administration, searches for immigrant crime, welfare, and reporting during the Trump administration increased by a factor of 1.36 to 2.45. For example, Google Trends data show that searches for immigrant and crime terms increased by a factor of 2.45 from the Obama administration to the Trump administration. By contrast, Bing shows that it increased by a factor of 1.8. Table 3 presents regression estimates for the effects of the administration change on immigration searches for both Google Trends and Bing and confirms that the effects of the Trump administration remain significant even after introducing a linear time trend.

Table 3. Immigration searches by presidential administration

∗p < 0.1; ∗∗p < 0.05; ∗∗∗p < 0.01.

Notes: After accounting for the linear time trend, there was still a clear increase in immigrant reporting searches after Trump's inauguration. Trump admin is a dummy variable of 1 when Date> 2017–01–20, and 0 otherwise. Bing regression is a binomial logit on a number of searches, with each search for a reporting search coded as 1 and a search for a non-reporting search term coded as 0. Standard errors are clustered by date. Google regression is OLS on monthly search interest.

The results presented here establish the existence of a sizable and persistent increase after Trump's inauguration in searches for immigrants and crime, immigrants and welfare, and methods for reporting immigrants to ICE. This manifests as a discontinuity immediately after the inauguration on 20 January 2017. Further, these results are highly consistent across both Google's and Bing's search data.

The amount and topic of anti-immigrant media coverage were closely related to the level of immigrant reporting searches, as shown in Table 4. On days when there was detailed media coverage of the immigration and crime topic, searches for reporting immigrants tended to be higher on both Bing and Google. Google searches were positively correlated with media coverage of immigration and welfare topics. Furthermore, these associations remained significant after controlling for the Trump administration, providing support for Hypothesis 2, which states that media coverage reinforcing the immigrant threat narrative leads to more reporting searches. These findings suggest a genuine relationship between media coverage and anti-immigrant searches that is driven by specific events rather than by the overall higher level of coverage of immigrant-related topics during the Trump administration. It is also important to note that the dummy variable for the Trump administration and the level of anti-immigrant media coverage have distinct and significant effects on reporting searches. Americans respond both to cues that the government supports deportations (Hypothesis 1) as well as to anti-immigrant media coverage (Hypothesis 2).

Table 4. Media coverage and reporting searches

∗p < 0.1; ∗∗p < 0.05; ∗∗∗p < 0.01.

Notes: The volume of immigrant crime coverage and overall immigrant-related coverage was positively associated with higher search rates for immigrant reporting in both Bing and Google searches. The volume of immigrant welfare coverage is positively associated with immigrant reporting Google searches. Bing Regression is a binomial logit with standard errors clustered by date. OLS yields substantively similar results (see appendix). Google Regression is OLS on daily Google data. Please see the appendix for equivalent tables about immigrant/crime and immigrant/welfare searches.

While there was a significant increase in negative coverage of immigrants after Trump's inauguration, the Trump administration also engaged in substantial anti-immigrant messaging and policy initiatives. Linking immigration to crime has been a significant messaging strategy of the Trump administration to justify its restrictive immigration policies, and these results suggest that this message is effective at mobilizing interest in denunciation. This raises the issue of whether media coverage of the Trump administration's anti-immigrant messages sparked the increase in anti-immigrant searches.

To test these hypotheses further, we look at the number of mentions of the word ‘Trump’ in daily immigration coverage. When the Trump campaign or Trump administration emits anti-immigrant cues, there is often significant media coverage of the event and thus an increase in immigration segments containing the word ‘Trump’. If the relationship between immigration coverage and anti-immigrant web searches is the direct result of Trump's words or actions, searches should be related to the amount of immigration coverage containing the word ‘Trump’ rather than overall immigration coverage or coverage of a specific immigration topic. To capture differences in cue-taking during the campaign versus the Trump administration, we also include an interaction between a number of segments of immigration-Trump coverage and the Trump administration variable. Recall that Hypothesis 1 predicts that only cues emitted by ‘President Trump, but not Candidate Trump’ would increase reporting searches, as only President Trump can shape immigration policy and ensure that denunciations of immigrants to ICE will have the intended effect.

The results of these tests, shown in Table 5, demonstrate that while there was a relationship between Trump's messages and reporting searches, the effects of news coverage on immigration searches were not solely the result of Trump's cues on immigration. Even when the Trump coverage variable and its interaction with the Trump administration is included in the regression, the strong relationship between immigrant searches and coverage of the immigrant + crime and immigrant + welfare topics does not decline in significance. This further supports Hypothesis 2, as it shows that anti-immigrant messaging, specifically, had an effect on reporting searches even when not accompanied by presidential rhetoric.

Table 5. Immigration coverage, administration actions, and reporting searches

∗p < 0.1; ∗∗p < 0.05; ∗∗∗p < 0.01.

Notes: Controlling for the amount of Trump-immigration coverage does not weaken the relationship between anti-immigrant coverage and anti-immigrant searches. The Trump News variable is not significant, indicating that during the campaign, Trump's statements on immigration had no relationship with anti-immigrant searches. The interaction between Trump News and Trump Admin, while significant, does not weaken the relationship between the crime/welfare news coverage and anti-immigrant searches. Bing regression is a binomial logit with standard errors clustered by day, and Google regression is OLS.

Regarding Trump's campaign cues, the regressions did not show a significant positive effect of Trump's immigration coverage on anti-immigrant searches during the campaign. However, the cues about Trump's presidential immigration policy positively and significantly affected reporting searches. Both of these findings provide further support for Hypothesis 1. Furthermore, these results confirm the distinct effects of pro-deportation government cues and immigrant threat cues on reporting interest.

Finally, we examine the role of negative emotional cues in reporting searches. Hypothesis 3 states that fear cues should have a positive relationship with reporting searches. Table 6 shows the result of regressing reporting searches onto anger, fear, sadness, and disgust cues. We find that across both Bing and Google searches, days with higher proportions of immigrant fear cues generated more immigrant reporting searches, providing support for Hypothesis 3. However, both crime and welfare topics are correlated with certain emotional cues (most notably, immigrant crime coverage contains a great number of fear cues). Is it possible that the topic and emotional cue variables are measuring the same phenomenon? To test this possibility, we include the daily level of immigrant crime and immigrant welfare coverage in the last two columns of Table 6. We find that both sets of cues continue to have a positive and significant relationship with reporting searches, suggesting that they are measuring separate phenomena. While immigration and crime coverage does have a large number of fear cues, it appears that the immigrant threat narrative itself has a distinct relationship with immigrant denunciation interest beyond its relationship with fear cues.

Table 6. Emotional cues and anti-immigrant searches

∗p < 0.1; ∗∗p < 0.05; ∗∗∗p < 0.01.

Notes: Immigrant fear cues in news transcripts were positively associated with higher search rates for immigrant reporting in both Bing and Google searches. The association remains significant even after controlling for immigrant crime and welfare topics. Bing regression is a binomial logit with standard errors clustered by date. OLS yields substantively similar results (see appendix). Google Regression is OLS on daily Google data. Please see the appendix for equivalent tables about immigrant/crime and immigrant/welfare searches.

In summary, when comparing immigration coverage with immigration searches, after controlling for the presidential administration, on days with more news coverage of immigration, there were more anti-immigrant Bing and Google searches. Furthermore, the topic of the news coverage had a significant impact on reporting searches; on days with more immigrant crime coverage, there were more anti-immigrant searches. This relationship is not attributable to media coverage of Trump's anti-immigrant cues, although the Trump administration cues supported more punitive policies toward immigration and also increased reporting searches. Immigrant fear cues also play a distinct role in encouraging reporting searches. These findings show a clear and consistent relationship between anti-immigrant media coverage and reporting interest. In the next section, we further isolate the effect of anti-immigrant broadcasts on reporting searches by looking at hourly searches during presidential speeches.

Anti-Immigrant Searches Increase During Broadcasts of Speeches by Trump

Our final set of analyses examines the direct effect of anti-immigrant media broadcasts on immigrant reporting searches. To test this, we look at televised speeches by both President Obama and President Trump. The speeches in our sample average 40.65 million viewers and each contains multiple mentions of immigration. Given the anti-immigrant content of Trump's speeches, we expect to see a spike in anti-immigrant searches during his speeches. We do not expect to see the same increases during Obama's speeches as they do not contain anti-immigrant content. Furthermore, we also examine searches at the same time, precisely one week before and one week after the speech, to ensure that any changes in searches during the presidential speeches are not the result of a time-of-day effect.

Our analyses reveal that the volume of anti-immigrant searches, including immigrant reporting searches, did spike during televised broadcasts of speeches by President Trump. Figure 5 shows hourly Google searches for reporting crime and welfare during Trump's 2017, 2018, and 2019 SOTUs and Oval Office addresses and compares them to Obama's 2015 and 2016 SOTUs. The plot also compares these searches with searches for the same terms one week before the speech and one week after the speech. There were clear spikes for reporting, crime, and welfare during President Trump's speeches, but there were no corresponding spikes during President Obama's speeches.

Figure 5. Anti-immigrant searches on google during presidential speeches.

Notes: There were clear spikes in anti-immigrant searches during Trump's televised addresses but no similar spikes during Obama's televised addresses. Each point represents one hour of Google Trends data. The dashed lines represent speech times.

The Y-axes of the plots are comparable within, but not between, days. A rating of 100 represents the hour with the most searches on that specific date but is not comparable with searches for other dates. For Bing results, please refer to the appendix.

Furthermore, there was no increase in searches at the same time of day, precisely one week before and one week after the speech, which suggests that the increase in searches can be attributed to the speech itself rather than any time effects. The results shown in Table 7 confirm the statistical significance of these search spikes, as the interaction between speech date and speech hour is positive and significant only for Trump but not Obama.Footnote 14 This signifies the unusual spike in anti-immigrant searches during televised Trump speeches.

Table 7. Google immigration searches during presidential speeches

∗p < 0.1; ∗∗p < 0.05; ∗∗∗p < 0.01.

Notes: There was a significant spike in Google searches for immigrant crime, welfare, and reporting during Trump's speeches. Regression is OLS. The Speech Date variable is 1 if the search was performed on the date of the speech and 0 otherwise (that is, performed exactly one week before or after the speech). The speech hour variable is 1 if the search was performed during the hours of 9 pm or 10 pm EST (except for the Oval Office speech, which is only 9 pm EST).

While all four of Trump's speeches prompted a spike in crime searches, and three resulted in a welfare spike, only the last two resulted in a spike in reporting searches (Table 8). What was different between these last two speeches? To answer this question, we examined the negative emotional cues (anger, disgust, fear, and sadness) in speech sentences that mentioned immigration. Figure 6 shows that Trump's first two speeches showed little increase in negative emotional cues in paragraphs about immigration compared to Obama's. However, his 2019 Oval Office address showed markedly different emotional valence, containing the most negative cues in immigration paragraphs of all of the speeches. This is especially notable given that it was also the shortest, running to approximately ten minutes compared to the rest of the speeches, which were hour-long SOTUs. Of all of the speeches, it also generated the largest spike in reporting searches.Footnote 15 Trump's 2019 speeches were, in general, more negative towards immigrants, with a greater focus on unauthorized immigrants.

Table 8. Speech content and search types

Notes: Variance in Trump's speech content corresponds with variance in search spikes. Search spikes correspond with the anti-immigrant content in the speech. X denotes a statistically significant search spike at p < 0.05.

1 Number of mentions of ‘illegal immigr’, “illegals, or “illegal alien” during the speech.

2 Obama stated, ‘Immigrants aren't the principal reason [why] wages haven't gone up.’

3 Trump described a merit-based immigration programme that would admit ‘people who are skilled, who want to work, who will contribute to our society’ but stopped short of claiming that unauthorized immigrants are costly or a burden on public services, as he did in the 2017 SOTU, 2019 SOTU, and 2019 Oval Office addresses.

Figure 6. Negative emotional cues in immigration paragraphs of presidential speeches.

Notes: This plot shows the number of negative emotional words in presidential speech sentences containing the terms ‘immigr*’, ‘illegals’, or ‘illegal alien’. Trump's 2019 Oval Office address showed the highest level of negative emotional cues in sentences containing the aforementioned terms.

In summary, there was a clear and sharp increase in anti-immigrant web searches during Trump's speeches but not during Obama's. While all four of Trump's speeches generated web searches for the anti-immigrant topics he explicitly mentioned in the speech (crime and welfare), only the last two generated spikes in reporting searches. In the first two speeches, viewers picked up on Trump's anti-immigrant cues and searched for them, but these messages did not translate into reporting interest. The last two speeches, however, were particularly negative towards immigrants, suggesting that the content of an anti-immigrant broadcast is critical in determining whether it will pique interest in reporting. The 2019 Oval Office address, which generated historic levels of reporting searches, also had the largest number of negative emotional cues towards immigrants despite being only one-sixth the length of the other speeches.

Conclusion

Does anti-immigrant media coverage lead to interest in denunciation of immigrants to ICE? We find evidence that it does. We examine three distinct effects of media cues on immigrant reporting searches. First, we look at the role of cues suggesting government support for deportations. There is more interest in immigrant denunciation when people believe that reporting will lead to some action by the government. We find that reporting searches increased sharply after Trump took office and that media reporting on Trump's immigration policies during his administration (but not during the Trump campaign) is associated with more reporting searches.

Next, we look at messages within media coverage about immigrants themselves. We find that media cues supporting the immigrant threat narrative are associated with more reporting searches, as are media messages about immigration that include fear cues. Even though these two sets of cues are correlated, they have distinct effects on reporting searches.

Finally, we investigate the effect that widely-watched anti-immigrant media broadcasts have on hourly searches about immigration. We find that anti-immigrant searches spiked during Trump's televised addresses but not during Obama's. Furthermore, we find that the content and emotional valence of speech influences the type of search terms that spike. Trump's speeches that talked about immigration and welfare generated immigration and welfare searches, while those that had negative emotional cues towards immigrants generated more immigrant reporting searches.

These findings have serious implications for media coverage of immigration. First, anti-immigrant media coverage, especially coverage of immigrants and crime, has the potential to cause serious and tangible negative impacts on immigrants' well-being. A media story that repeats inaccurate claims about immigrants and crime could pique interest in deportations, leading to threats, harassment, or arrests of people suspected to be unauthorized immigrants. Immigrants have reported ‘living in fear’Footnote 16 under the Trump administration, and anti-immigrant news coverage may make these fears come to fruition.

The second implication concerns news coverage of Trump's speeches and other statements. While there was significant media debate over the live airing of Trump's 2019 Oval Office address, networks ultimately chose to broadcast the address. After the broadcast, news outlets called the address a ‘dud’Footnote 17 and ‘bewildering’,Footnote 18 concluding that, unless the address motivated Americans to call their Congress members, ‘Trump's speech changed nothing’.Footnote 19 Even if Trump's address did not have substantial political impacts or change the hearts and minds of the population at large, it resulted in one of the largest-ever spikes in Google searches on reporting immigrants, suggesting that at least some reports to ICE of immigrants were made as a result of the speech. Airing anti-immigrant statements to a large audience may eventually lead to serious harm to immigrants.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123423000558.

For access to the raw Bing search count data, please get in touch with David Rothschild at [email protected]

Data availability statement

Replication data for this article can be found in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/VCBKP4

Financial support

None.

Competing interests

None.