Despite the constant and quick development of new technologies in the service of heritage, the digital turn in museums has not contributed to novel forms of storytelling in obvious ways (Copplestone and Dunne Reference Copplestone and Dunne2017), nor has it lessened museums’ typical reliance on visual communication (Classen and Howes Reference Classen, Howes, Gosden, Edwards and Phillips2006; Favro Reference Favro, Bond and Houston2013; Geismar Reference Geismar2018). Many digital exhibitions—and the narratives they offer—are still tied to nondigital structures (Copplestone and Dunne Reference Copplestone and Dunne2017; Perry Reference Perry, Chapman and Wylie2015). For example, lengthy texts on panels—typical for a traditional, contextual model of a display (Vergo Reference Vergo and Vergo1989)—are now presented on digital tablets (Kidd Reference Kidd2014). Given the excitement about digital exhibitions, in many cases the only revolution we see is a change of medium orchestrated by the museums’ IT departments. One must ask whether such displays are merely superficial means to make public institutions seem more attractive and progressive. Are they simply conveying the same stories and failing to make use of any new possibilities born of the digital turn in archaeological museums?

Polish archaeological displays provide interesting sites through which to explore these multilayered questions. In the following short review, I aim to describe and evaluate the digitally mediated temporary display Treasures of Peru: The Royal Tomb at Castillo de Huarmey, at the State Ethnographic Museum in Warsaw in 2018. I claim that, first of all, the success of this exhibition lies in the rejection of a pattern established in Poland for digital museums; second, the display offers a new way of understanding the entanglement of the digital and material in the archaeological museum; and third, the curators of the exhibition successfully escape the usual solution, in which the digital is imposed on an analog narrative.

DIGITAL “BOOM” IN POLISH MUSEUMS

Poland offers an interesting ground on which to examine digital displays. Since 2004, when the country joined the European Union and was able to apply for special funds devoted to the development of cultural infrastructure, Poles have built or rearranged about 100 multimedia museums and/or exhibitions. The pioneering example of the best digital exhibition, according to most Polish museum scholars (Kowal and Wolska-Pabian Reference Kowal and Wolska-Pabian2019), is the Warsaw Rising Museum, an institution that opened in 2004. The inauguration of this museum stands as the beginning of the Polish “museum boom,” resulting in an intensive pattern of opening new museums and exhibitions. The Warsaw Rising Museum forged a type of “narrative display” that is common to these new institutions (Folga-Januszewska and Kowal Reference Folga-Januszewska, Kowal, Kowal and Wolska-Pabian2019) and characterized by extensive use of varied multimedia (videos, audio recordings, digital tablets, visualizations, simulations, reconstructions) that “give voice” to and engage the material artifacts in a presented storyline. Multimedia are arranged in dimmed spaces, and they invite audiences to become immersed in past events and histories. The director of the Warsaw Rising Museum explained that the implementation of digital tools facilitates communication with visitors (although he does not explain what this entails) and gives the exhibition a “reliability” in the eyes of younger audiences (Ołdakowski Reference Ołdakowski, Kowal and Wolska-Pabian2019:76).

New museums that follow this scheme are historic, and they tend to focus on the recent past—namely on two periods that crucially shaped Polish identity: World War II (Kowal and Wolska-Pabian Reference Kowal and Wolska-Pabian2019) and Communism (Ziębińska-Witek Reference Ziębińska-Witek2018). The narrative and aesthetic pattern they use is clichéd for two reasons. First of all, to increase visitor numbers, they typically follow the standard “narrative display” created by the Warsaw Rising Museum, seeking to mimic their narrative to achieve success with audience attendance. Secondly, a handful of companies—namely New Amsterdam, Adventure Multimedialne Muzea, and Nizio Design International—rule the Polish digital exhibitions market. For instance, one company specializes in creating multimedia tram wagons that visitors enter to enjoy a video or play on a tablet. If the museum tells the story of prewar times, the wagon is designed as if from the 1920s. If it deals with Communism, the same wagon is stylized as from the 1960s. Even though they are far from original, reproducing only known solutions (Figure 1), these digital displays are generously financed by state authorities, who, in many cases, offer special funding programs for digital culture. A visible “digital preference” of the government results in a further increase of rehashed digital exhibitions and museums in Poland, even though many scholars openly criticize them (Kowal Reference Kowal, Kowal and Wolska-Pabian2019; Ziębińska-Witek Reference Ziębińska-Witek, Kostro, Wóycicki and Wysocki2014, Reference Ziębińska-Witek2018).

FIGURE 1. An example of a copy-and-paste solution in Polish digital museums: a destroyed wall from a Polish building dating to the World War II period. The hole is filled with a multimedia screen showing a ruined city. Museum of the Second World War in Gdańsk. Photograph by Monika Stobiecka.

More and more museums (including archaeological ones, e.g., Rynek Underground in Kraków, Museum of Archaeology and History in Elbląg, Piast Tower in Opole) are turning digital, following the same narrative display approach and hoping to attract more visitors. In the end, however, they struggle with familiar criticisms: they are accused of presenting visions of the past that are not believable, depriving the collections of material objects, and offering “flat experiences” that lack educational value. In contrast, the exhibition that I discuss below rejects the standardized pattern and creates an original solution for archaeological artifacts.

DIGITALLY EXPLORING THE MATERIAL TREASURES OF PERU

The temporary exhibition at the State Ethnographic Museum in Warsaw, Treasures of Peru: The Royal Tomb at Castillo de Huarmey, took place between December 15, 2017, and May 27, 2018 (Giersz and Prządka-Giersz Reference Giersz and Prządka-Giersz2018; Giersz and Prządka-Giersz, eds. Reference Giersz and Prządka-Giersz2018). It grew out of a collaboration between the Castillo de Huarmey Archaeological Project; the State Ethnographic Museum in Warsaw; the National Museum of Archaeology, Anthropology, and History of Peru in Lima; the Ministry of Culture in Peru; and the Polish Society of Latin-American Studies. Originally displayed in Lima, the exhibition traveled to Poland, where it was prepared together with the architectural studio Medusa Group and the graphic studio DEM Interactive. It presented finds from the archaeological site of Castillo de Huarmey, where an international archaeological mission led by Miłosz Giersz and Patrycja Prządka-Giersz has been conducting long-term research. The spectacular uncovering of an untouched royal tomb has been widely recognized as the most important discovery of 2013, as described by the American magazine Archaeology. It was later featured as the cover story on National Geographic magazine's June 2014 issue. The exhibition consisted of four spacious rooms presenting the history of the site and findings through a variety of analog and digital exhibits. Visitors would enter the display and find themselves in a wide room, whose design imitated the natural landscape of the archaeological site's surroundings. The floor was covered with gritted beige sand, and the visitors moved on it on a wooden track. Irregularly placed wooden boxes with showcases presented artifacts excavated from Castillo de Huarmey. Above the heads of visitors, there was a flat ceiling made of white blotting paper. This aesthetic installation resembled the lower horizon in Peru (Figure 2). Colors, installations, and showcases created a convincing effect of immersion, where no digital tools were needed. The display was advertised as multimedia in nature, which might have led visitors to expect the standard structure of digital immersion that is popular in Poland, where one enters a dark room and is immediately bombarded by many stimuli. Here, the opposite happened. The interplay between all the elements (decorations, artifacts, and natural materials such as sand and wood) smoothly introduced visitors into the realm of archaeological investigations. Personal linkages with the archaeologists, whose photograph was presented in the first room, were also used to create a more intimate connection between the visitors and the curators/archaeologists.

FIGURE 2. The passage from the first to the second room of the exhibition Treasures of Peru: The Royal Tomb at Castillo de Huarmey, State Ethnographic Museum in Warsaw. Photograph by Monika Stobiecka.

The second room was designed to host a digital showcase. There were digital reconstructions, visualizations, and a virtual reality experience (a tour of the archaeological site). This digital room was purely informative, attractively presenting historical and archaeological facts. Instead of lengthy texts, visitors were given a chance to see a digital archaeological workshop (i.e., GIS-related materials such as satellite photos, a movie presenting archaeological works with drones, 3D scanners, etc.) and a variety of other materials visually explaining work at the archaeological site. When entering this room during the guided tours organized by Giersz and Prządka-Giersz, the digital archaeological specialists Marta Bura and Janusz Janowski would join the tour and explain in detail all the materials and technologies used at the excavations.

The next room, a black cube, hosted the most spectacular result of the archaeological studies at the site to date—the hyperrealistic facial reconstruction of a Wari queen (Figure 3). The original model was accompanied by two screens, one of them presenting a moving reconstruction of the queen's head, the other showing an archaeological visualization of the reversed taphonomical process.

FIGURE 3. Facial reconstruction of the Huarmey Wari Queen accompanied by a virtual model (on the left) and the reconstruction of the archaeological context (on the right). State Ethnographic Museum in Warsaw. Photograph by Monika Stobiecka.

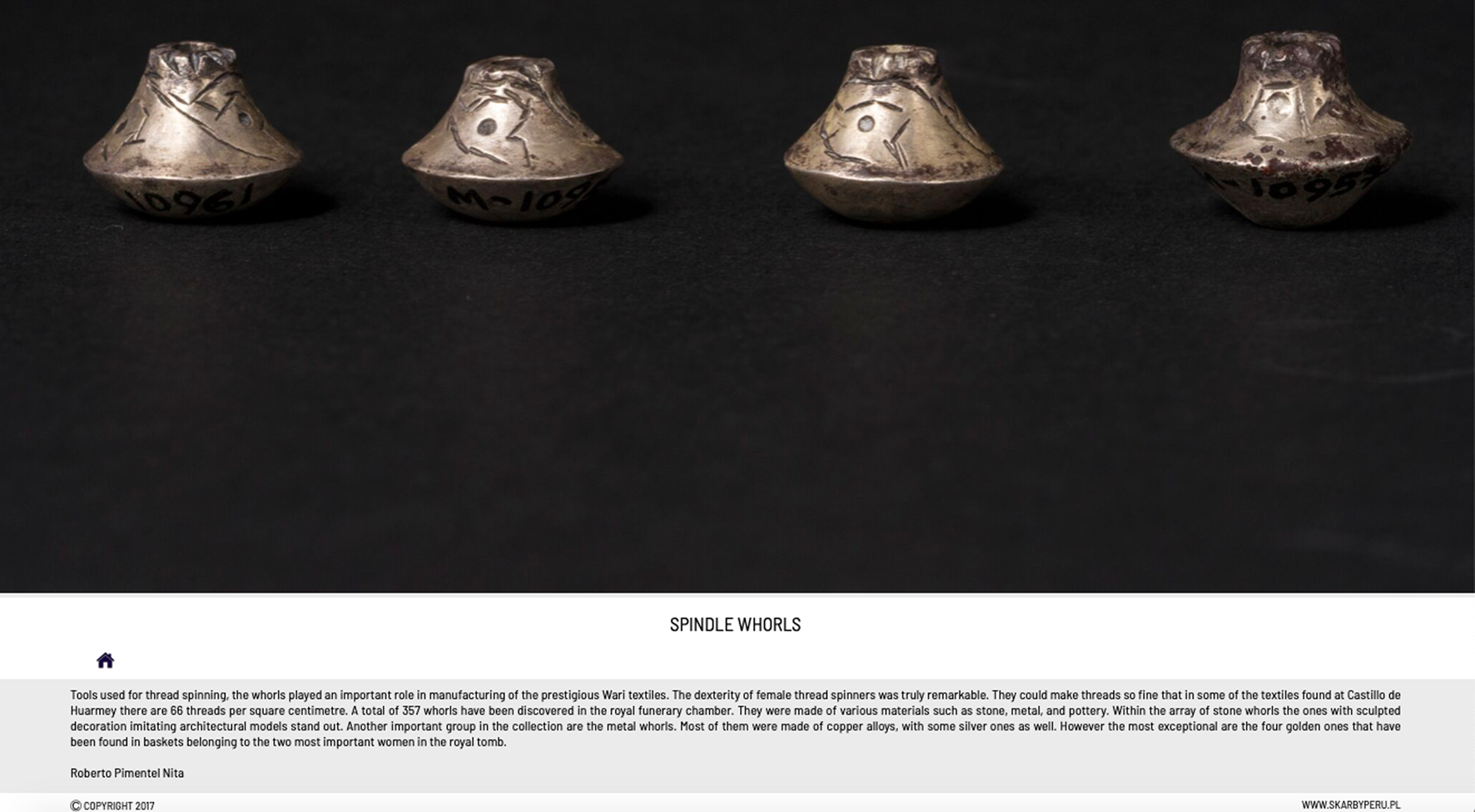

The greatest innovation of this exhibition, however, was waiting for visitors in the last room. Here, visitors entered to see many wooden boxes stacked against the walls (Figure 4) and a wooden structure, resembling the Castillo de Huarmey mud-brick and stone architecture, placed in the center of the room (Figure 5). The intent was to allow visitors to climb the structure and look for QR codes. After scanning a code, visitors could retrieve textual and/or visual information (photos, movable models, short videos showing artifacts in different stages of exploration or conservation accompanied by short descriptions, etc.; Figure 6) from the official website's database, which is still accessible (Skarby Peru Reference Peru2017), as is the virtual tour (Peru Virtual Exhibition 2017). It should be mentioned that the information was diverse and did not follow a predictable pattern of presentation. Visitors were encouraged to explore the material content of the room (search for the QR codes), as well as the digital content of the database. What could be a better means to show archaeology than to motivate the public to uncover artifacts and information? Even though QR technology is one of the simplest methods to provide digital content to tangible objects, curators proved that it could be used in an engaging way. Visitors, whether children or adults, were visibly enjoying the exhibit, wandering around the boxes, climbing the structure, and searching for codes that would tell them more about the objects. In this sense, I believe that the last room presented the essence of archaeology while effectively escaping from the typical digital display pattern in Poland.

FIGURE 4. Wooden showcases placed against the walls with original artifacts and QR codes irregularly positioned around the displays. State Ethnographic Museum in Warsaw. Photograph by Monika Stobiecka.

FIGURE 5. The wooden structure with hidden artifacts and QR codes that was often crowded with visitors acting as explorers. State Ethnographic Museum in Warsaw. Photograph by Monika Stobiecka.

FIGURE 6. An example of an entry redirected from a QR code scan: short information featuring a high-quality, aesthetic photograph. Accessed at http://www.skarbyperu.pl/63/en/. State Ethnographic Museum in Warsaw.

I interviewed Prządka-Giersz and Giersz, the archaeologists who excavated Castillo de Huarmey, about how they handled the preparation of the display. Encouraged by the director of the State Ethnographic Museum, they invited a renowned professional architect, Przemo Łukasik, to be responsible for the exhibition's aesthetics. Furthermore, they collaborated with specialists in digital archaeology so as to avoid copy-and-paste patterns common to other Polish museums. While the architect focused on the aesthetics and design, inspired by information provided by scholars, the archaeologists prepared the content, including information panels, descriptions on the website accessed through QR codes, and guided tours. In contrast to typical Polish digital displays prepared by outsourced companies with little influence by scholars, it is no surprise that Treasures of Peru: The Royal Tomb at Castillo de Huarmey was so strikingly coherent. The exhibition also differed from other displays in terms of aesthetics. Instead of immersion in dark cellars, visitors were given a chance to grasp the natural environment of Peru.

CONCLUSIONS

Many digitally mediated exhibitions fail at providing new types of narration, merely exchanging the analog for the digital. In contrast, the exhibition discussed here was prepared by scholars, an architect, and digital specialists, and it offered a holistic, engaging, and original experience based on scientific and professional content. The curatorial staff did not seek ready-made solutions provided by external companies. Instead, they worked closely with the material collections, not simply with immaterial “content” (cf. Hanussek Reference Hanussek2020). Technology that was used to engage visitors was not the latest and most innovative, but rather an attractive, digitally supported display with a coherent vision resulting from a fusion of different perspectives. Consequently, Treasures of Peru: The Royal Tomb at Castillo de Huarmey proved that thinking about digital archaeological exhibitions should start not with technologies but rather with multiple conceptual insights. Only by deploying different views can digital archaeological museums start a critical reflection upon the challenges posed by new technologies.

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my gratitude to Miłosz Giersz and Patrycja Prządka-Giersz for personal communication and an exhaustive explanation of the display's objectives. Marta Bura, a digital archaeologist who participated in the works, was also an important source of information about the digitization techniques, and I wish to thank her here. I would like to thank Sara Perry for commenting on a draft version of this review.