Introduction

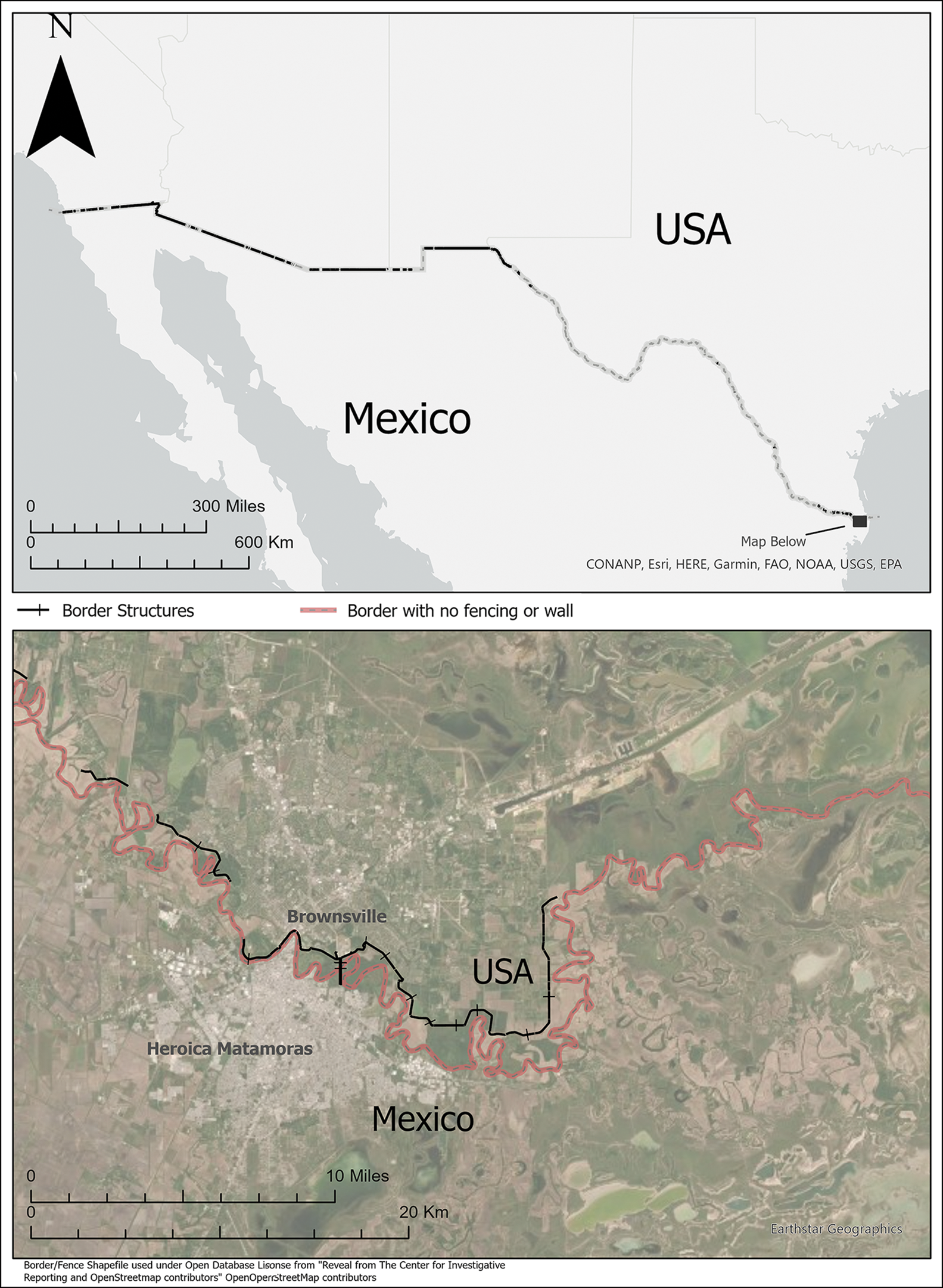

The physical demarcation of borders may have lasting effects on a landscape. Border walls may leave physical traces and affect social relationships and practices long after those walls cease to function. This phenomenon is well illustrated by the northern frontier of the Roman Empire, which stretches across present-day northern England: Hadrian's Wall (Figures 1 & 2). Commonly perceived today as a hard boundary between civilisation and outsiders (Hingley Reference Hingley, Kaminski-Jones and Kaminski-Jones2020), the persistent materiality of Hadrian's Wall serves to normalise discourse around other more recent borders, such as the US/Mexico border (Figures 3). As Bonacchi (Reference Bonacchi2022: 122) has recently observed, various frontier works of classical antiquity, such as Hadrian's Wall, are drawn into these contemporary debates through their representation in the press and in popular articles written by archaeologists. These socio-political narratives generate a powerful continuity between past and present. We argue that archaeologists have not fully addressed the consequences of this politicisation of ancient borders. In order to counter the appropriation of these borders for contemporary nationalistic political agendas, archaeologists must explicitly recognise and address the imagined continuities of border landscapes.

Figure 1. Photograph of part of Hadrian's Wall, near Housesteads, Northumberland (photograph by E. Hanscam).

Figure 2. Maps of Hadrian's Wall and the Roman Empire (figure by B. Buchanan).

Figure 3. Maps of the US/Mexico border (figure by B. Buchanan).

Popular perceptions of Hadrian's Wall often equate the structure with the modern-day border between England and Scotland, though it has never served that function (Brophy Reference Brophy, Gleave, Williams and Clarke2020: 59), and it has been frequently appropriated within current nationalistic disputes in the UK and the USA. Commentators from across the political spectrum, for example, sought to compare former President Trump's efforts to build a wall along the US/Mexico border with Hadrian's Wall (Flynn Reference Flynn2019; Jenkins Reference Jenkins2019). Writing for the New Yorker on the eve of Trump's inauguration, de Monchaux (Reference de Monchaux2016) remarked that:

The remains of Hadrian's Wall, which was completed around the year 128 C.E., still span Scotland between the North Sea and the Irish Sea. All this time later, some distant Anglo-American memory of it may help to explain the political power behind the idea of a wall—even as theories suggest that this wall's purpose may have been very different, perhaps directly opposite, from that of the wall evoked by our President-elect.

Examples such as this illustrate why archaeologists must recognise the potent material legacy of such ancient borders, how they are reworked amid wider political debates, and how their continued existence promotes inequality in other border spaces. By considering the relationship between borderlands such as Hadrian's Wall and the US/Mexico border, we gain insight into how archaeology, as a discipline, operates within the contemporary world.

In particular, as scholarly research on past borders is drawn into fraught contemporary debates, we have begun to see the opening of a significant gap between the public perception of border zones and theoretical innovation in archaeology. Clarke and colleagues (Reference Clarke, Gleave, Williams, Gleave, Williams and Clarke2020: 2) note that “the broader task of public archaeologies of frontiers and borderlands is an as-yet largely unexplored field”, and one that must be developed. This is particularly pressing in the context of the development and reliance on hard boundaries—often demarcated by walls—as forms of control (Cooper & Tinning Reference Cooper and Tinning2019; McAtackney & McGuire Reference McAtackney and McGuire2020); such boundaries may draw inspiration from the material remains of the past and the popular and scholarly discourse around them. Border theory also has an important political and social dimension (Shanks Reference Shanks2012). A recent multidisciplinary renewal of interest in borders and borderland theory (e.g. Amilhat Szary & Giraut Reference Amilhat Szary and Giraut2015) has led to a newly developing field of critical border studies (Parker & Vaughan-Williams Reference Parker and Vaughan-Williams2016). Indeed, archaeology has its own long history of studying borders, boundaries and frontiers (e.g. Naum Reference Naum2010); such research, however, rarely factors into modern discussions of border zones. It is vital that archaeologists address this situation, especially since, as we demonstrate below, the scholarly study of ancient borders normalises modern boundaries.

Here, we compare two landscapes (Hadrian's Wall and the US/Mexico border) constructed two millennia apart, because they are frequently linked in the media, particularly in the context of the discourse surrounding immigration during the 2016 US presidential election and Trump's subsequent immigration ban (see Bonacchi Reference Bonacchi2022), and because they illustrate how the uncritical portrayal of the material past can affect the present. Their comparison allows us to see how the normalisation of the materiality of Hadrian's Wall has resulted in the imagined materiality of the US/Mexico border. Archaeologists including De León (Reference De León2015), McGuire (Reference McGuire2013), McGuire & Van Dyke (Reference McGuire, Van Dyke, Sheridan and McGuire2019), McAtackney & McGuire (Reference McAtackney and McGuire2020) and Soto (Reference Soto2018) have studied the US/Mexico border from an archaeological perspective that echoes that of recent research on Hadrian's Wall (e.g. Hingley Reference Hingley, Kaminski-Jones and Kaminski-Jones2020; Symonds Reference Symonds2020), underlining the reflexive relationship between ancient and modern borders. Through this comparison, we aim to show how the material past facilitates inequality in the present, and how awareness of this relationship encourages a more socially engaged and resilient archaeology.

Monumental afterlives and living frontiers

While Hadrian's Wall has traditionally been considered to be a defensive structure intended to protect the Roman province of Britannia from the ‘barbarians’ to the north, more recent approaches argue that it functioned as a multi-faceted complex used to observe and manage human mobility, and/or was constructed as a symbol of Roman power and authority (Breeze & Dobson Reference Breeze and Dobson2000; Hingley Reference Hingley2012; Collins & Symonds Reference Collins, Symonds, Collins and Symonds2013; Symonds Reference Symonds2020). Although it is one of the most heavily researched features of Roman Britain, comparatively few studies focus on the ways in which preconceptions of the Wall influence the socio-political landscape of modern-day Britain (Breeze Reference Breeze2019: 159; exceptions include Witcher Reference Witcher2010; Hingley Reference Hingley2012, Reference Hingley, Kaminski-Jones and Kaminski-Jones2020; Brophy Reference Brophy, Gleave, Williams and Clarke2020). Recent studies of the post-Roman history of the Wall demonstrate its enduring importance in discussions surrounding the origins of British identity (e.g. Hingley Reference Hingley, Kaminski-Jones and Kaminski-Jones2020), and the continuing social impact of the monument (Symonds Reference Symonds2020). Yet, despite Hadrian's Wall being repeatedly referenced in debates about the importance of modern border walls for defence and immigration, there is a significant gap between public perceptions of the monument and wider theoretical innovations concerning archaeological borderlands. For example, archaeologists frequently portray the Wall as a multicultural space, within which “almost every corner of the empire can be seen represented” (Nesbitt Reference Nesbitt, Millett, Revell and Moore2016: 240; though for a critique of multicultural readings of Roman frontiers for perpetuating the inequalities they aspire to address, see Witcher Reference Witcher, Pitts and Versluys2015: 202). Despite such plural narratives, however, many visitors continue to experience the material remains of the Wall through the lens of barbarian (‘them’) and Roman (‘us’) (see Witcher Reference Witcher2010). This leaves us questioning why the studies cited above have not had more impact. Here, we contend that archaeologists must acknowledge and explore how the materiality of the Wall and the narratives woven around it can serve to perpetuate inequalities in the contemporary world.

In demarcating the northern frontier of the Roman Empire, Hadrian's Wall monumentalised a division of social and physical space that has been variously replicated over time. In the process, the Wall has become an archetypal ancient border to which modern nation-states have looked as part of a modelling of their own imperial missions on the Roman Empire (see e.g. Morley Reference Morley2010). Today, branding such as “Hadrian's Wall Country” (Hadrian's Wall Country n.d.) reinforces the popular misperception that the Wall forms part of the modern Anglo-Scottish border, when, in reality, the English county of Northumberland lies almost entirely to the north of the Wall (Hingley Reference Hingley, Kaminski-Jones and Kaminski-Jones2020: 201). Thus, there are two versions of Hadrian's Wall that we need to consider: the complex Roman frontier landscape studied by scholars, and the popularly ‘imagined’ version that divides peoples and spaces. The material persistence of the Wall has encouraged a simplification of a complex socio-cultural reality. In turn, this uncritical understanding normalises the discourse around modern ‘walled’ borders.

Modern borders and boundaries have a long-term impact on how groups of people relate to each other. It is no accident that the US/Mexico border ‘wall’—a glorified fence that extends along only some sections of the border—is far more present in popular discourse than any other US border. Indeed, “the border between the United States and Mexico is not just a line on a map […] in the American imagination, it has become a symbolic boundary between the United States and a threatening world” (Massey Reference Massey2016: 160). US immigration laws have always sought fundamentally to protect an imaginary white United States; thus it is the border with the (supposedly) racially different Mexico that is of greatest concern (Jones Reference Jones2021: 5). In many respects, the US/Mexico border ‘wall’ of the popular imagination mirrors the public perception of Hadrian's Wall; Bonacchi (Reference Bonacchi2022: 137) emphasises the repeated connections between ‘Trump's wall’ and Hadrian's Wall that can be found in US commentary and journalism and on social media.

Trump's repeated promise to build a wall stretching the length of the US/Mexico border (more than 3000km) was key to his 2016 presidential campaign. What was delivered, however, was largely upgrades to existing border fences and the modest addition of approximately 125km of new barriers, leaving most of the border unmarked. Nonetheless, even the short distance of border works that was constructed constitutes an environmental and humanitarian disaster, inflicting damage to national parks and the ancestral lands of the Tohono O'odham Nation in Arizona (cf. McAtackney & McGuire Reference McAtackney and McGuire2020). Like Hadrian's Wall, the popular perception of the US/Mexico border is not aligned with reality: although sections are militarised and the most accessible crossing points are blocked (Jones Reference Jones2016), it is not an impenetrable ‘hard border’; sections of built wall (Figure 4) can be transgressed using power tools or rope ladders. Furthermore, 2000km of the border are demarcated by the Rio Grande, a landscape that mostly lacks barriers other than the river and the remote Texan landscape (Figure 5). The boundary has become more than physical; it is a symbolic separation enforced by dogmatic, partisan politics within the USA. Indeed, the material reality of the US/Mexico wall has receded as its (mis)perception as a hard border has been magnified through political debate. This misalignment of the physical and imagined qualities of the border is akin to the situation on Hadrian's Wall, where the complexity of the material remains and their significance are simplified in popular and political discourse.

Figure 4. US/Mexico border wall between Sunland Park, New Mexico, USA, and Anapra, Chihuahua, Mexico (image by D. Lyon, January 2019, via Wikimedia Commons, under CC BY-SA 4.0 licence: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0).

Figure 5. The US/Mexico border on the Rio Grande (image by Glysiak, April 2014, via Wikimedia Commons, under CC BY-SA 4.0 licence: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0).

Archaeologists studying the landscape of the US/Mexico border have consistently recognised the potential humanitarian impact of their research. McGuire (Reference McGuire2013: 467–68) emphasises that the materiality of the border has real consequences, constraining people's lives, although it is important to note that it also has the capacity to generate agency. McGuire (Reference McGuire2020: 181) writes that archaeologists study barriers, such as the US/Mexico border, as an assemblage composed of three parts: “the neoliberal state, the material wall, and the human bodies of those who attempt to move across the barriers”. De León's (Reference De León2015: 5) Undocumented Migrant Project (https://www.undocumentedmigrationproject.org/home) records and collects the material traces left by those who try to cross the border, with an explicit focus on understanding and illuminating the human cost of US border enforcement. Soto (Reference Soto2018) similarly documents items abandoned along the Arizona/Sonora border, focusing on the ‘afterlives’ of such objects and emphasising their presence as ‘modern ruins’, poised between refuse and heritage. These projects contribute to an understanding of the ongoing humanitarian crisis on the US/Mexico border, one fuelled immediately by the harshness of the natural landscape (Figure 5) rather than by border structures—although it is the latter that directs migrants to these inhospitable locations. And yet the myth of the border wall remains, in no small part due to the continued material presence, and appropriations, of border spaces such as Hadrian's Wall.

Borders and the landscape in the present

Archaeologists are strongly positioned to push back on popular narratives surrounding border spaces. Part of archaeology's importance and relevance is its ability to examine key concepts over the longue durée; for example, how each generation understands Hadrian's Wall in different ways (Hingley Reference Hingley2012). The physical monumentalisation of such boundaries permits this long-term perspective. In the case of the US/Mexico border, Trump's vision of the physical—and figurative—wall will affect US/Mexico relations for years to come. Similarly, Hadrian's Wall will likely remain embedded within contemporary discourse related to issues of politics or identity in the UK and beyond. Should Scotland proceed with a second independence referendum, for example, Hadrian's Wall will inevitably be drawn into the debate. Contemporary society as a whole therefore requires a better understanding of how perceptions of the materialities of the archaeological past can influence today's world, especially in the case of highly politicised border landscapes.

Theoretical approaches to borderlands can help here, provided research is constructive and accessible. One potential way forward is to combine new materialist approaches with Ingold's (Reference Ingold1993) work on dwelling perspectives. This provides the scope to consider the material record of past people who lived in a landscape alongside the agency of assemblages—formed by natural and artificial landscape features, assemblages can influence the interaction between people and landscape. Nesbitt's (Reference Nesbitt, Millett, Revell and Moore2016) work on Hadrian's Wall provides an example, as does Sundberg's work (Reference Sundberg2011), which emphasises the agency of the materiality of the US/Mexico border. Sundberg argues that the hills and arroyos of the Sonora Desert affect the visibility and policing of the region by border patrols. This assemblage of wall, desert, plants, river and weather combines to define the geopolitical border between the USA and Mexico.

There is great potential within a holistic assemblage-based approach to apprehend the power of popular perceptions of borders such as the US/Mexico border and Hadrian's Wall. By starting from a perspective in which the ‘pastness’ of frontier works is not the immediate or sole concern, we can understand how the materiality of walls influences the present, before seeking to interrogate its past. This facilitates a landscape-based ‘dwelling perspective’, which emphasises how the landscape consists of a record of those who have lived within it and left something of themselves behind. Landscape perception is thereby based on remembrance, of “engaging perceptually with an environment that is pregnant with its past” (Ingold Reference Ingold1993: 152). From this perspective, the ways in which landscapes have been perceived—over centuries—are seen to be rooted in the imagination. This is an approach that research on recent and modern borders, boundaries and frontiers has yet to engage with fully.

Archaeologists must engage explicitly with the imagined narratives imposed on past materialities. Geographers have demonstrated that border walls do not work (Dear Reference Dear2013; Wright Reference Wright2019), at least not in the ways popularly imagined. Hence, as long as public perceptions of materiality of ancient frontiers such as Hadrian's Wall remain unchallenged by current scholarly accounts, contemporary border walls will continue to derive legitimacy from the past. Archaeological research on Roman frontiers (and borders generally) must not only be relevant to contemporary discussions of borders, but also influential on them. How can this be accomplished? The task goes beyond the study of archaeological borders, or of Roman frontiers, and has broad implications for the future of archaeology.

A resilient archaeology for a global future

It is vital that archaeologists examine the changing complexities in their discipline's relationship with current political action. One question, revived in the light of factors such as the resurgence of right-wing populism (see Babić et al. Reference Babić2017; González-Ruibal et al. Reference González-Ruibal, González and Criado-Boado2018; Popa Reference Popa2019), is whether archaeologists should embrace the political nature of the discipline and express their personal views as political actors. This question has been asked before (e.g. Tilley Reference Tilley, Pinksy and Wylie1989; cf. Shanks & Tilley Reference Shanks and Tilley1989; McGuire Reference McGuire2008), but it is one that must be asked again, as the global context of archaeology changes. We practise archaeology at a time when it has been suggested that academics should declare their political affiliations alongside their expertise (Singh & Malnick Reference Singh and Malnick2021). Discussions of the past feature increasingly in prominent debates across political and cultural arenas; however, archaeological perspectives are either wilfully misconstrued, completely ignored or countered with belligerent reactions against ‘experts’ (for one recent prominent example, see the reception of ‘Ancient Apocalypse’ on Netflix (Dibble Reference Dibble2022; Heritage Reference Heritage2022)).

This is a challenging time for archaeology. As critical dialogue about the past grows, efforts to suppress these dialogues similarly gain strength. In countries such as the UK and USA, growing numbers of archaeology, Classics, history and anthropology departments face redundancies or closure. This is not unanticipated; Gardner (Reference Gardner2018: 1662) highlighted that, without recognition of archaeology's relevance for our present world, “it is hard to see how public support for archaeology as exists might be sustained”. The problem, as he and others (e.g. Brophy Reference Brophy2018) see it, lies in how to acknowledge and sustain an archaeological discourse that is relevant to contemporary questions without encouraging political abuse. There is a tension between pursuing archaeology in its current form as a discipline that pursues its own goals and transforming it to meet present and future societal needs. Potential solutions, however, need not be in conflict.

Mickel and Olson (Reference Mickel and Olson2021) urge archaeologists to be activists, as their unique perspectives and expertise allow them to examine and interpret the stories of the most marginalised groups in societies. They argue that archaeologists should engage with social justice by reorientating their research to appeal to groups beyond academia. Similarly, given the current threat to the arts, humanities and social sciences, Smith (Reference Smith2021) considers archaeology to be especially vulnerable because it can be seen as irrelevant. Some archaeologists, therefore, are increasingly embracing the more seemingly ‘objective’ related disciplines, such as ancient DNA research, perhaps partially because of political concerns (Ion Reference Ion2017: 181; see commentary in Nilsson Stutz Reference Nilsson Stutz2018). Yet, in an era when colleagues in other scientific disciplines are also ignored or accused of political bias, this seems untenable.

Consequently, we contend that archaeology is in an unsustainable situation. If we do not emphasise the continued social relevance and importance of archaeology, the discipline will be further marginalised and defunded, and our ability to represent the past will be lost. On the other hand, if we publicly emphasise the political nature of archaeology, scholars will be increasingly drawn into simplistic and partisan debates. The uncritical analysis of the past is frequently drawn upon in opposition to movements such as Black Lives Matter, for example when the UK Culture Secretary Oliver Dowden (Reference Dowden2021), writing in The Sunday Telegraph, stated “We won't allow Britain's history to be cancelled”. Meanwhile, in the USA, the conservative right has united against the way in which history is taught in public schools, using the supposed teaching of critical race theory as a rallying cry against the dissemination of multifaceted views of the American past (Waxman Reference Waxman2021). In contexts such as these, we argue that the idea that the study of the past can continue uncritically is imbued with privilege, and the continued portrayal of the material remains of the past without recognition of their impact on the lives of people in the present is flawed.

We contend that archaeologists must be politically proactive and should seek to understand how their work may be politically used and abused. We need to demonstrate that our discipline has critically independent value and meaning. Our expert understanding of the past, which is relevant to many contemporary issues, should allow us to be explicit about our narrative-building; our interpretations not only illuminate the past, but also help address current concerns, such as the UN's Sustainable Development Goals (Allen et al. Reference Allen2022).

Archaeological interpretations complement other disciplines by providing a nuanced perspective on key contemporary issues, aided by the deep chronological range of our datasets. To help combat global challenges such as climate change, it is important that we pursue interdisciplinary research rather than persist in disciplinary isolation (Rick & Sandweiss Reference Rick and Sandweiss2020). While many archaeologists regularly engage with these complexities, the popular perception of archaeology is that it is only concerned with the ‘treasures’ of the past. The pressures of the ‘publish or perish’ cycle and the requirements of national rankings in academia, and the fact that many archaeologists work in development-led archaeology, can make it difficult to engage with present-day political concerns. Yet, if we do not actively engage with the political ramifications of our work, archaeology may continue to be seen as a vanity degree instead of a vibrant, multidisciplinary field of study that engages with complex issues of human development and practice. Since archaeology is popular with the media, we have a unique opportunity to engage with and shape public understanding, but only if we more deeply rethink the narratives that link the past to the present. If we do not, we risk contributing unwittingly to ongoing humanitarian issues through our uncritical portrayal of the past.

Our comparison of Hadrian's Wall with the US/Mexico border highlights the need for archaeologists to engage with the powerful imagined continuity between past and present landscapes, and how the materiality of past borders continues to impact on the present. This relationship requires archaeologists to take political action. Choosing to recognise the potential humanitarian impact of our research, particularly that of ancient border landscapes frequently linked to modern realities, is political action. Intentionally framing research questions addressing how landscapes reveal long-term dwelling perspectives rooted in the imagination is also political action. There is a substantial humanitarian cost in the continued uncritical portrayal of past material landscapes, particularly border spaces, which makes an apolitical archaeological position untenable.

Acknowledgements

Our thanks to Richard Hingley, David Petts and Yvonne Marshall for commenting on draft versions of this article; their time and effort was very much appreciated. Thanks also to the two anonymous reviewers, and to everyone at Antiquity.

Funding statement

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency or from commercial and not-for-profit sectors.