In 1910, Sophie IonFootnote 1 Meritz, an African woman in the employment of a German policeman at a small station in colonial German South West Africa (present-day Namibia) pressed charges against another German policeman from a nearby town. In her deposition, she accused the latter of rape. She claimed that the man had ‘made [her] have sexual intercourse by force’, that ‘because he was stronger than me, he threw me on the bed, held my arms, and then used me’. In the same document, the African woman also stated that her alleged rapist ‘had used [her] sexually several times’ but that later she had ‘given herself up willingly’. ‘Only once,’ she noted, had she ‘received and accepted 5 Marks for this’. She added that she was also ‘being sexually used’ by her employer, that she had had ‘a child from a white [person]’ before, and that apart from the two policemen, ‘other white men have also used me sexually’.Footnote 2

Sources like this woman’s statement are quite rare in the German colonial archive.Footnote 3 They hint at a social reality that was common but seldom put on the official record. We owe it to Sophie Meritz, who bravely pleaded her case with the colonial authorities, despite the risks involved in such an endeavour. What her particular testimony reveals is the broad spectrum of possible sexual relations that occurred between colonizers and colonized – ranging from consensual sex, through concubinage and prostitution, to rape – in this case condensed in one single statement. Despite evidential difficulties, scholarship has firmly established by now that sexual relationships between white men and indigenous women were the norm, not the exception, within the German colonies (Brockmeyer Reference Brockmeyer2021; Habermas Reference Habermas2016; Hartmann Reference Hartmann, Bechhaus-Gerst and Klein-Arendt2003) and elsewhere.Footnote 4 Yet, at the turn of the twentieth century, these relationships, in particular the so-called Mischehen (mixed marriages), came increasingly under scrutiny from multiple sides (notably missionaries, doctors, scientists and colonial officials), for they threatened notions of racial order and public health, as well as Christian, bourgeois morality (Aitken Reference Aitken2007: 95–145; El-Tayeb Reference El-Tayeb, Mazon and Steingrover2005; Kundrus Reference Kundrus, Janz and Schönpflug2014; Lindner Reference Lindner2009; Walther Reference Walther2015; Wildenthal Reference Wildenthal2001: 79–130).

This article offers a microhistory of the Sophie Meritz case. What I wish to discover in this small-scale investigation are the larger implications: what do the (violent) sexual acts of two German policemen and the desperate steps of an African woman to stop them tell us about existing cultural codes and gender identities in the colony, and what do they tell us about the workings of the colonial state in the intimate spaces of German South West Africa? I argue that Sophie Meritz sought to participate in the discussion over the meaning of sex and violence within the colony’s quotidian social tissue. But, ultimately, her articulation of what these intimate, physical interactions meant to her collided with the policemen’s understanding of masculine honour and comradeship. Following Ann Stoler’s dictum that matters of intimacy were matters of the state (Stoler Reference Stoler2002), and heeding Penelope Edmonds and Amanda Nettelbeck’s reminder that colonial governance was ‘strongly inflected by affect and personal connections’ (Reference Edmonds, Nettelbeck, Edmonds and Nettelbeck2018: 2), I propose that discussions of rape and intimate violence were also always negotiations over the nature of colonial power, the state and its project.

The wars and post-war policing

The policemen of the case study were part of the Mounted Police of German South West Africa (Berittene Landespolizei für Deutsch Südwest) (Muschalek Reference Muschalek2019; Zollmann Reference Zollmann2010). This force was founded in 1905, in the midst of wars of annihilation (1904–08) that the German army waged against the indigenous populations of South West Africa who had taken up arms to fight against colonial oppression, dispossession and settler intrusion. The Herero–German and Nama–German wars unleashed unparalleled levels of violence and suffering over south-western Africa that culminated in the first genocide of the twentieth century. Tens of thousands of Africans were killed during the war, perished on their flight into the Kalahari desert, or died in concentration camps.Footnote 5 Forced labour and war imprisonment persisted well into the years after the end of the wars. Thus, the 1910 events of the Sophie Meritz case unfolded in a radically altered post-war society in which social and political organizational structures had been almost entirely destroyed and in which survivors sought to rebuild their communities, through precolonial kinship relations (Krautwald Reference Krautwald2022: 41–87), for instance.

Charged with the ‘maintenance of public peace and security’,Footnote 6 the mixed-race, semi-military, semi-civilian police force of about 700 men operated to establish a post-war order. On their remote posts, forced into intimate communities they had rarely chosen, small units of two to six black, mixed-race and white policemen lived and worked. Given the extent of the people and territory they sought to bring under their dominance, the number of state officials was vanishingly low. The police’s possibilities to formally control German South West Africa were quite limited, and their organization has been described as dysfunctional (Juan et al. Reference Juan, Krautwald and Pierskalla2017; Zollmann Reference Zollmann2010). Yet, in the everyday, an informal, improvised way of proceeding emerged: in the field – i.e. in their intimate encounters with the population – policemen blended idiosyncratic bureaucratic technologies with ‘petty’, normalized acts of violence, administrative procedure with military habitus, sociability with professional duty (Muschalek Reference Muschalek, Rud and Ivarsson2017; Reference Muschalek2019). Guiding them was a strong adherence to honour codes – as becomes clear in the events discussed in this article.

Racial hierarchies

The colonial record described Sophie Meritz as a ‘Bastardweib’Footnote 7 – a term used by contemporary Germans to designate interchangeably both so-called ‘Mischlinge’ (children of white men and black women) and the discrete mixed-race population group who self-identified as Basters (Steinmetz Reference Steinmetz2007: 227). Her surnameFootnote 8 and reference to her kin’s Nama name make it unlikely that she belonged to the latter, an Afrikaans-speaking community, descendants of Cape Dutch and Boer men and Nama and Khoi-San women, who had settled in the Rehoboth area of today’s central Namibia in the late 1860s and early 1870s (Britz et al. Reference Britz, Lang and Limpricht1999; Budack Reference Budack2015; Limpricht Reference Limpricht2012). This notwithstanding, Sophie Meritz’s racial status was distinct from that of other black women, and it is worth contemplating what that in-between position might have allowed her to do in social and cultural terms. As a socio-political entity, mixed-race people were a product of the white supremacist state and its racist ideology, which, as Mohamed Adhikari notes, ‘cast people deemed to be of mixed racial origin as a distinct, stigmatised social stratum between the dominant white minority and the African majority’ (Reference Adhikari and Adhikari2009: ix). However, crucially, this group’s members also shaped their own identity, asserting their intermediate and exclusive position in the racial hierarchy (Erichsen Reference Erichsen2008: 39–43; Limpricht Reference Limpricht2012).

The German post-war regime of strict regulations and surveillance (Steinmetz Reference Steinmetz2007: 144–216; Zimmerer Reference Zimmerer2001), which prohibited Africans from owning land and livestock, restricted their movement, obligated them to wear identification tags – all measures to generate and control an impoverished, dispossessed African workforce for the growing white settler encroachment – was not aimed at Basters. But the government’s sustained (and, after 1905, radicalizing) ideological and political efforts to fix and separate racial difference were. Mixed-race Africans were often the prominent object of fearful discussions on ‘miscegenation’ (Henrichsen Reference Henrichsen, Bechhaus-Gerst and Leutner2009; Kundrus Reference Kundrus, Janz and Schönpflug2014; Lindner Reference Lindner2009; Todd Reference Todd, Pugach, Pizzo and Blackler2020; Wildenthal Reference Wildenthal2001: 79–130). No other group, Dag Henrichsen observes, was surveilled as much by the colonial state, which constantly scrutinized ‘their way of life, their morality and thus ultimately also their bodies and sexuality’ (Reference Henrichsen, Bechhaus-Gerst and Leutner2009: 80). Ethnographic discourses on race mixing, like that of infamous German eugenicist Eugen Fischer (Reference Fischer1913),Footnote 9 oscillated between positive and negative assessments of their character traits, social features and cultural development. They were considered either superior to and more civilized than black Africans because of the beneficial ‘admixture of white blood’ (Bayer Reference Bayer1906: 646) or, to the contrary, particularly suspicious because the blood mixing had combined ‘the worst characteristics of both parents’.Footnote 10 Colonial law treated mixed-race subjects as ‘natives’ (Eingeborene), and subsequent decrees and court decisions prohibited and retroactively annulled marital unions between them and ‘non-natives’ (Aitken Reference Aitken2007: 109–17; cf. Henrichsen Reference Henrichsen, Bechhaus-Gerst and Leutner2009; Steinmetz Reference Steinmetz2007: 224). Thus, although Sophie Meritz was most probably not Baster, the colonial perception of her as either suspicious or more ‘advanced’ in the racial hierarchy still applied.

Act 1: white male honour and ‘uncomradely behaviour’

Sophie Meritz’s initial deposition, which she filed in March 1910, a month before the one quoted in the introduction, is lost – together with the statement of her surmised assailant and any other connected court records. Only a few court files from the German regime in South West Africa remain in the German Federal Archives in Berlin. The relevant files of the district court in Keetmanshoop responsible for the Meritz case are not among them. My investigation in Berlin has shown that a collection of documents pertaining to the Meritz case was filed in a folder entitled ‘General native affairs’, which – unfortunately – is listed as missing.Footnote 11 In the Namibian National Archives in Windhoek, neither the files of the responsible district office in Bethanie nor the ones of the nearby Keetmanshoop administration contain any related records. However, the Berlin Archives hold an extensive correspondence between different agencies of the police and the colonial administration pertaining to the case, including several testimonies by settlers from the surrounding area and the final court ruling.Footnote 12 Despite its lacunae, the available documentation offers compelling insight into how colonial authorities dealt with the disruptive (sexual) behaviour of one of their own.

The policemen in question were Sergeant (Sgt) Karl Geffke, the woman’s employer, and Sgt Johann Höning, the presumed rapist. Geffke had come to South West Africa in late 1904 with the Schutztruppe (German colonial army) to fight the Herero.Footnote 13 Höning had joined the colonial troops of German South West Africa in 1901.Footnote 14 Both men had transferred from the military to the police force after the end of the war in 1907. Over the years of their service, both received mixed evaluations from their superiors: Geffke, a tall, lean, blond, blue-eyed man,Footnote 15 was commended for being an ‘extraordinarily energetic’Footnote 16 soldier and a ‘diligent, faithful civil servant’.Footnote 17 He was also described, however, as ‘tending towards harassment and the pursuit of his self-interests’ and as having a ‘limp outside appearance’.Footnote 18 Höning, on the other hand, had a short, ‘bloated figure’, yet ‘good military bearing’.Footnote 19 He was characterized nevertheless as a ‘bad comrade’ who ‘tended to self-aggrandizement’.Footnote 20 The two men had in common that they were said to be particularly ‘adept’ communicators, especially in written form.Footnote 21

The first person to deal with the Meritz affair was the two policemen’s direct civilian superior, acting District Chief Ferse, from the district office located in Bethanie. He treated it as a disciplinary matter. And he felt confident that he could settle it internally. Enclosing Meritz’s deposition, he reported back to the two policemen’s immediate military superior, Lieutenant Müller, at police depot Spitzkoppe (which was another 100 kilometres away). In his report, Ferse dismissed the woman’s allegations out of hand. He was convinced that she had lied. ‘[There] is no doubt that the plaint against Höning for violation is completely unfounded. The woman says definitely the untruth,’ he noted.Footnote 22 As a woman ideologically and legally marked as ‘native’, Meritz’s voice was threefold silenced: first, by the contemporary racist dictum that all Africans and people of mixed-race heritage were notorious liars; second, by the contemporary sexist notion that women were prone to fantasize and to concoct false accusations, notably when it came to sexual violence; and third, by the both racist and sexist idea that African women were particularly libidinous (Bourke Reference Bourke2008; Reference Bourke, Edwards, Penn and Winter2020; Hommen Reference Hommen1999: 87–92; Lauro Reference Lauro, Herzog and Schields2021; Mühlhäuser Reference Mühlhäuser, Gudehus and Christ2013: 168; Scully Reference Scully1995; Thornberry Reference Thornberry2016; Reference Thornberry2018: 155–62, 201–5). As Elizabeth Thornberry (Reference Thornberry2018: 154) has shown for the Eastern Cape, rape trials did not investigate the assailant’s identity or whether the crime had taken place, but instead ‘turned on the credibility of the individual complainant’, linking women’s ability to tell the truth to ‘questions of civilization and respectability’. Meritz’s attempt at differentiation, her enumeration of the several varying qualities of sexual relationships she had engaged in with the two men, was for Ferse an indication that ‘she constantly entangled herself in contradictions during police questioning’.Footnote 23 The real reason for her accusation, he claimed, was that ‘she was afraid Geffke would order her off the station because of her infidelity’.Footnote 24 And thus, as final ‘proof’ he put forward that she was ‘known everywhere as a big whore’.Footnote 25 He attached a local farmer’s testimony that stated almost verbatim the same slander.Footnote 26 This last point damned Meritz irrevocably. Women who were considered promiscuous, whether they had had sex for payment or had conceived children out of wedlock – and following her own account both applied to Meritz – could simply not claim to have been the victim of a rape (Mühlhäuser Reference Mühlhäuser, Gudehus and Christ2013: 168; Thornberry Reference Thornberry2016). Thus, the ‘evidence’ against her was considered so overwhelming that no further investigation was ordered. With this verdict, the Meritz case should have been dismissed and closed, as most incidents of sexual assault were, and still are.

But the matter was not over yet. The acting district chief suspected that the African woman had not acted alone. He reckoned that her employer and sexual patron, Sgt Geffke, must have incited her to make the recriminations. He wrote, ‘Unfortunately, we do not have the means to punish Geffke for his uncomradely behaviour … It is one’s word against another’s word. I expressed my disapproval about the incident, though, and reprimanded him. I further ordered him to remove the woman from the station immediately.’Footnote 27 And so, while Sophie Meritz’s perspective was irrelevant to the acting district chief, he turned his attention to his men’s behaviour. Regulating the relationship between the two now became his main concern. And even though he admitted that there were two competing accounts of the truth, Ferse had singled out his culprit. To him, Geffke’s ‘uncomradely’ conduct was the core of the problem. He had broken the code of loyalty and esprit de corps among men, notably among members of the police force, when he had turned against one of his own over the question of who was granted sexual access to a local woman. How that access was achieved, whether violently or non-violently, was of lesser importance to the acting district chief. In closing, Ferse stated that he had instructed the other policeman, Sgt Höning, ‘to curb his sexual drive a little and to avoid such unpleasant occurrences’.Footnote 28 Again, the potential violence of Höning’s sexual urges became a secondary issue. Like many of his contemporaries, the local administrator understood his subordinate’s impulses to be natural, especially in the colonial context. He simply took issue with Höning’s disregard for the rules of discretion (cf. Hartmann Reference Hartmann2007: 41).

The colonial government in Windhoek, however, took a different stand. In a slightly irritated tone, it demanded an explanation from the local administrator as to why he had not brought the case before the local court.Footnote 29 The letter, which was countersigned by the head of police, stated that all cases of offences ‘requiring public prosecution’ – and rape had been such an offence since 1876 (according to sections 176 and 177 of the penal code) (Hommen Reference Hommen1999: 48–9) – ‘regardless whether these are committed against a white [person] or a coloured native’ had to be passed on ‘urgently’ and ‘under all circumstances’ to the responsible judge.Footnote 30 In its struggle for legitimacy, both police and administration leadership agreed that upholding the notion that the colonial state was operating according to the rule of law was imperative (Schwirck Reference Schwirck1998; Zollmann Reference Zollmann2010: 30–2, 341).Footnote 31 Interestingly, the letter made no allusion at all to the rape case itself or to the necessity to regulate more consistently policemen’s sexuality. Those concerns seemed not worth repeating but were taken seriously enough to be brought in front of a court of justice.

Acting District Chief Ferse retorted to his superiors that, if the case were allowed to go to court, ‘even if resulting in a termination of the proceedings or an acquittal, it will harm the police force’s reputation’.Footnote 32 He went so far as to suggest that any admission of criminal cases put forward by colonized subjects themselves without the intermediary revision of the colonial administration would inevitably end in ‘great damage to the reputation of the white race’.Footnote 33 Despite these protestations, the Sophie Meritz case went to the local court in Keetmanshoop. Shortly thereafter, in July 1910, the judge decided not to open a legal procedure for lack of proof. He added to his decision that, ‘in fact, following Meritz’s own account, one must assume that she did not offer any serious resistance against Höning’s advances’.Footnote 34

Comradeship between policemen and the good name of the police force, and by extension of the colonial state and even of the entire ‘white race’, were thus at the core of the conversation in the Meritz case.

Honour, masculinity, sex

Like other men in the colonial realm, policemen in German South West Africa sought above all to be respectable (Muschalek Reference Muschalek2013; Schmidt Reference Schmidt, Naranch and Eley2014; Smith Reference Smith, Ames, Klotz and Wildenthal2005). To them, this meant first and foremost to be strong, brave and dashing soldiers. What police headquarters wanted to see maintained was an impeccable military appearance. They believed that proper bearing and the lethal potential that it conveyed to be the most important source of the police force’s authority. Yet, policemen were also to be sensitive and calm professionals – guardians of the ‘peace’. They were to be fatherly figures embodying the paternal state.Footnote 35 These professional components of police identity did not always harmonize with the martial ones described above – nor did the different notions of masculinity underlying them. In fact, two competing models of masculinity pervaded the German colonies, crystallizing over the question of interracial sex and reproduction. One, that of ‘imperial patriarchy’, saw sex with African women as a white, male privilege. The other, that of ‘liberal nationalism’, saw sex not as ‘a man’s private decision, but a social marker of status’, in which ‘race mixing’ posed a serious threat to the colonial political order (Wildenthal Reference Wildenthal2001: 81, 83).

According to the colonial administration that had created the police force, policemen were supposed to be living examples of the colonial order. They were to lead stable, disciplined and respectable lives. Marriage with a European woman was a crucial element of this and was to prevent them from ‘going native’ (Axster Reference Axster2005). Unlike barracked soldiers, whose sexual practices were regulated by means of military discipline, medical controls and officially organized prostitution (Hartmann Reference Hartmann2007; Walther Reference Walther2015: 43–52), policemen were to enter matrimony, establish families and live in individual apartments or houses. Government officials had their doubts, however, whether the conditions in the colonies were right for such married lives. In 1911, the head of police conceded that they were not.Footnote 36 And given the widespread belief at the time, supported by medical discourse, that male sexuality was constantly under pressure that needed relief, especially in the hot climate of the colonies (Bischoff Reference Bischoff2011; Grosse Reference Grosse2000), ongoing sexual intercourse with the colonized was assumed and therefore condoned – especially on small, remote police outposts.

Consequently, the regulation manual that was to guide policemen in their daily work remained ambivalent when it came to contact with African women. It issued no straightforward interdiction, but rather a warning. The policeman was told that he had ‘the duty to show a particular reserve in contact with native women’.Footnote 37 For he should ‘bear in mind that through intimate intercourse with native women he indubitably lowers his moral sense’ and ‘forfeits his standing with the whites and the coloureds’.Footnote 38 A ‘particular duty’, the manual continued, fell to ‘the comrades’ who were to ‘divert’ colleagues who had ‘gone astray’.Footnote 39 One could argue that the two policemen of the Meritz case had heeded the manual’s advice, first by meddling in each other’s sexual affairs, and second by committing a sexual crime against a not entirely ‘native’, more ‘civilized’ woman, thus upholding their honour as defined by the frontier between black and white.

What mattered to the immediate superiors of rank-and-file policemen was that policemen’s sexual undertakings were kept as discreet as possible. What was seen as problematic was not sexual contact itself but rather that it was paraded in public, no matter whether it was consensual or forced, long term or short term, romantic love or utilitarian arrangement.Footnote 40 A senior staff sergeant noted, for instance, that one of his men was ‘having familiar intercourse with a native woman’, underlining that said policeman would regularly let her out of his room in the morning ‘when all the schoolchildren and Boers are on site’.Footnote 41 The presence of onlookers explained why he thought that the standing of the other policemen was being ‘harmed by this behaviour’.Footnote 42 In the case of a sergeant who exchanged love letters with an African woman from whom he was separated, his superiors observed that ‘formally’ he ‘had done nothing wrong’, but that his ‘intercourse with native women’ in general was ‘all too intimate and without any consideration for the public’.Footnote 43 Moreover, such recorded incidents of ‘indiscretions’ provide the evidence, though more tenuously and indirectly, that policemen thought these sexual encounters to be manly, invigorating achievements, and thus honourable feats – because the policemen did, after all, seem to have wanted to show off their ‘conquests’, proving their masculine virility.

When it came to everyday police violence, its meaning was tightly linked to notions of individual honour and the collective reputation of all police troops as well. Policemen aspired to be experts in violence. Their violent profession was inscribed in reasoned sentiments about ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ violence. Even when disapproved of by higher-ups, their violent practices normally made sense to the lower-downs in terms of masculine honour (Muschalek Reference Muschalek2013). Combining the two practices – that is, when sexual practices became violent – I propose that men of the Landespolizei exhibited features of ‘honourable’ masculinity that were highly malleable. In the Meritz case, the lower police echelons, represented by acting District Chief Ferse and the two German police sergeants, favoured an imperialist patriarchy model, within which sexually predatory behaviour was not necessarily conceived of as wrong. It could be a form of adventurous and pioneering conduct, but it needed to follow the rules of comradely, loyal conduct. To put it in crude terms, to these men on the spot, rape could be an acceptable form of ‘honourable’ violence, but only if they shared their ‘prey’ fraternally and discreetly. For police headquarters, their guiding principle was the liberal nationalist model of masculinity according to which men were to keep their sexual drives in check. This notion of masculine self-control included that policemen would not resort to violence that was unlawful. It found expression, if only obliquely, in the insistence on legal prosecution. Even more important to the leadership was that police respectability would not be undermined by the events. And thus, we return to the Meritz case and the way in which an incident of seemingly ‘private’ interpersonal violence eventually became an affair of state secrecy.

The case had important aftermaths in the winter of 1910. For after it had been sent to the local court, events took a turn. Now, Sgt Höning sued his colleague for libel.Footnote 44 Apparently, Geffke had talked extensively and repeatedly about the rape case among farmers in the region.Footnote 45 Having spread the rumour and having supported Sophie Meritz in her endeavours, Sgt Geffke had ‘shown an utterly base attitude’ and had harmed the reputation of his comrades and employing institution, acting District Chief Ferse claimed.Footnote 46 Once again, the district chief suggested that the matter should not be pursued in court, for it ‘would only confirm Geffke’s guilt’.Footnote 47 He requested instead that the sergeant be immediately removed from the force since he was ‘not worthy to wear the police uniform any more’.Footnote 48 And, indeed, police headquarters reacted promptly: the police sergeant received his discharge, together with a disciplinary penance of seven days in prison.Footnote 49 The case of sexual offence had entirely faded in the light of the sergeant’s ‘malicious’ disloyal conduct, which constituted a violation of his obligation to official secrecy. The higher and lower echelons had closed ranks. Cohesion and stateliness needed to be immediately and decisively re-established for they were the essential markers of state authority.

Act 2: Sophie Meritz’s bid for respectability

Another story, different from the one about ‘honourable’ violence and comradeship, is possible but harder to substantiate: one that explores the possible motives and plausible strategies of Sophie Meritz as she pled her case before the German authorities, even though this was an enormously risky enterprise. Let us start over and approach the tenuous evidence again – this time from her perspective. This second part is deliberately more speculative, but I believe that there is an argument to be made about her actions being about respectability as well.

Sophie Meritz went to find employment in the ||Karas region in 1905 or 1906. The police station where she and her employer lived and worked was named Kunjas. It was situated in a mountainous, arid hinterland, in the southern part of the colony, about fifty kilometres (a day’s ride on horseback) from the next administrative town, Bethanie, where the accused policeman Hönig was stationed. Outposts such as Kunjas were isolated, lonely places, inhabited by a handful of people. According to the archival record, two white unmarried men were stationed there in 1910.Footnote 50 An African police assistant named Josef worked at the station as well, together with probably one or two other black policemen.Footnote 51 To these we have to add an unspecified number of auxiliaries and domestic service men and women. By sheer virtue of the small scale, interracial contact was frequent. That Kunjas was not an exclusively homosocial space (which did exist in other places) is evident given Meritz’s presence there. But whether she was the only woman at the station must remain unanswered.

At the time of the events, Sophie Meritz seemed to have been on her own, without family. She was ‘about twenty years’ old.Footnote 52 One source refers to her young age (‘almost still a child’)Footnote 53 when she started working at another police station four or five years prior to her employment in Kunjas. She did have kin, though. Evidence shows that ‘Simon Petrus, the bastard girl’s parents’, travelled through the area, and for a short while, when they stopped at the station, she lived with them at their wagon.Footnote 54 Meritz’s family might thus have belonged to the Oorlam people who settled around Bethanie in the nineteenth century, called !Aman (Hoernlé Reference Hoernlé1925). The war against the Nama had hit this population group particularly hard, resulting in an almost complete destruction of the !Aman social structure (Erichsen Reference Erichsen2008: 25–8), forcing their members to flee to South Africa or into the mountain caves to escape imprisonment in concentration camps and, if they returned, to seek employment removed from their kinship relations, like Meritz did.

Sex, intimacy and propriety

There are two crucial challenges historians of African sexualities have to contend with. First, they are faced with the ‘enduring legacy of colonial racial sexual stereotypes that portray African men and women as hypersexualized’ (Decker Reference Decker, Herzog and Schields2021: 42). Second, ‘the history of African sexualities is profoundly immersed in colonial ugliness, a litany of rape and other forms of sexual violence that cannot and must not be overlooked or downplayed by historians dedicated to understanding the meaning of sex and sexualities in the past’ (Erlank and Klausen Reference Erlank and Klausen2023: 86). However, this makes it hard to uncover less painful, more practical, or maybe even joyful sexual encounters. An article that tries to reconstruct the quotidian situation of intimate encounters between African women and German policemen risks falling into these traps of seeing violent sexual relationships everywhere, always. Hence, I would like to stress that, in the everyday, at secluded, distant police stations, sex was one form of intimacy that was embedded in a much broader quotidian economy of social interactions and labour relations. Despite the evidentiary lacunae, Sophie Meritz voiced her understanding of sex in which a whole spectrum of intimate interactions was conceivable to her.

She also confirmed having had several sexual partners. But sex, as she stated herself, was not her primary income source. She worked as a domestic help, as so many other colonized women did, because colonial rule had forced them into the (semi-free) wage labour economy. Above all, Meritz was needed as a cook (after her dismissal, her former employer was at a loss without her, complaining that he and his fellow policeman were ‘forced to cook for ourselves, despite our ignorance’Footnote 55 ). In all likelihood she also did laundry, cleaned, ran errands, and fulfilled all kinds of daily chores. I suggest that sex – coerced and/or consensual intercourse with her employer – was part of that labour relation. To her, sex might have been a currency, an exchange in a reciprocal albeit unequal relationship (cf. Hartmann Reference Hartmann, Bechhaus-Gerst and Klein-Arendt2003; Henrichsen Reference Henrichsen, Zimmerer and Zeller2016). Whether there was, in addition, an emotional attachment, and the nature of that affective intimacy, cannot be discerned from the archival evidence. The fact that Meritz’s employer ‘expressly’ noted that ‘she means absolutely nothing to me’ does make one pause, however, and wonder why he insisted so strongly on having no feelings for her.Footnote 56 After he had been ordered to dismiss her, he went to the surrounding farms in search of another domestic help, and explicitly asked for a woman again.Footnote 57

As for Sophie Meritz’s honour, we already learned that in the course of her trial it had been entirely dismissed by a whole host of white colonizer men. Yet, there are sources that can help reconstruct her own understanding of propriety. In contemporary ethnographic accounts of African sexual mores,Footnote 58 we learn that Nama as well as Baster morality dictated that women in particular took a prominent role in regulating and controlling household, family and reproductive matters and that unmarried sex was prohibited. If it occurred, redress was sought through beatings and/or material compensation (Bayer Reference Bayer1906: 646; Fischer Reference Fischer1913: 268–71; Hoernlé Reference Hoernlé1987: 69; Schultze Reference Schultze1907: 297–9, 319–1). Especially fertility and childbearing determined a woman’s standing. ‘Only infertility permanently and deeply lowers a [Nama] woman’s reputation’ (Schultze Reference Schultze1907: 299). Having a child out of wedlock was ‘considered a great disgrace’ (Hoernlé Reference Hoernlé1987: 96; cf. Fischer Reference Fischer1913: 268). Yet, as the anthropologist Winifred Hoernlé (Reference Hoernlé1987: 96) noted in her 1912 field diary, if the child was a girl, she could go and live with the father once she was grown, and ‘there was no further disgrace attached to the mother’. When Sophie Meritz declared that she had had at least one child with a European man, perhaps she was referring to this social norm in order to emphasize her own sexual propriety, her demonstrable past attempt to right a social wrong (although we do not know whether that child was still in her care or whether she had left it with the father). Maybe her statement was an effort to clarify all of her past sexual interactions and to measure them up to her own social standards.

Let us also imagine that when she went to present her case, Sophie Meritz put on her most respectable clothing. Memory Biwa (Reference Biwa, Du Pisani, Kössler and Lindeke2010: 331) reminds us of the importance of the ‘body, with all its materiality’ as ‘a site of communication and knowledge’ that can tell a story just as much as the spoken or written word. Instead of lamenting the incompleteness of the colonial written archive (as if it would have revealed all the answers, had it been complete), she proposes to listen to Nama oral narratives instead, including to the way in which women dressed in the past, but also chose to dress for the occasion of her interviews, uncovering how ‘these re-enactments through cloth were evidence of an alternative regime of historical knowledge’ (Biwa Reference Biwa2012: 98). Hence, despite the fact that there is no visual evidence of her, it is worth speculating on Sophie Meritz’s physical appearance and attire, how she presented herself – not to ask how it had a bearing on her sexuality, but rather to allow for the possibility that Meritz made clothing choices as a form of communicative agency when appearing in front of the colonial authorities.

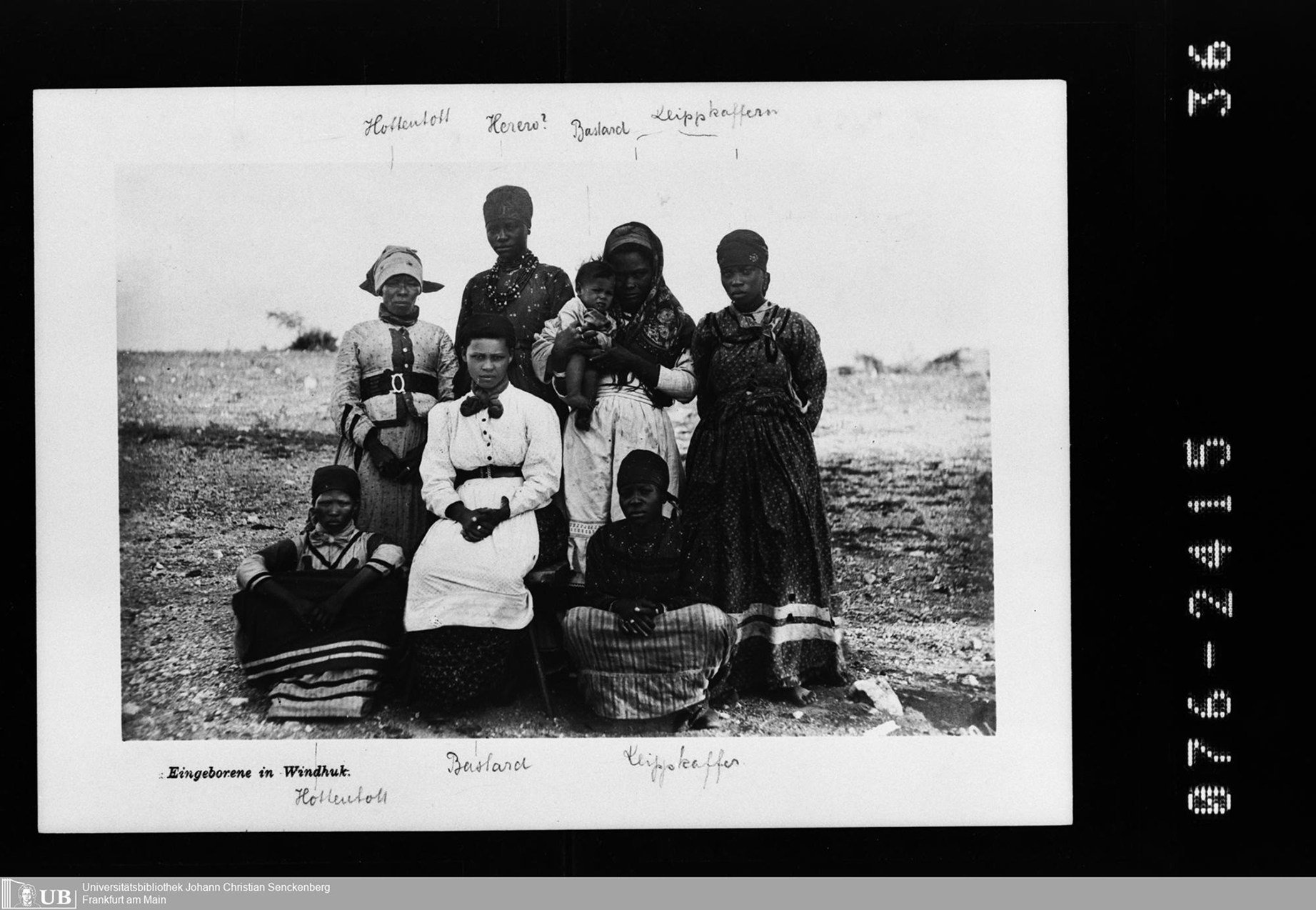

In contrast to the colonial imagery of African nudity proliferated in ethnographic photographs, cartoons and postcards from the era (cf. Axster Reference Axster2014; Geary Reference Geary and Thompson2008; Silvester et al. Reference Silvester, Hayes, Hartmann, Hartmann, Silvester and Hayes2001: 13–14), contemporary pictures taken of Baster and mixed-race women and girls for ethnographic purposes (Bayer Reference Bayer1906; Fischer Reference Fischer1913) underlined their intermediate, ‘semi-civilized’ status, showing them in Victorian-style clothing. These images suggest that Sophie Meritz might have been dressed in the manner of the Nama/Cape Dutch style of either Basters or of Nama women (Figure 1). She might have worn a skirt and buttoned blouse with a bow collar or scarf tied high around her neck, an apron, most likely a head wrap or a bonnet, or both. Fischer (Reference Fischer1913: 256–7) noted in his study that, for special occasions, the bonnet was usually worn on top of the wrap. Betraying his coercive methods, he added (ibid.: 257) that it was considered unseemly for Herero and Nama as well as Baster women to uncover their head in front of men, and that the young Baster women ‘were very ashamed’ when told to take off their head wrap to be photographed or measured. Exoticizing their ‘racy facial features’ and the contrast between their dark skin and ‘the dazzling white’ of their teeth, Bayer (Reference Bayer1906: 646) insisted that Baster women ‘rightly enjoy the reputation of loveliness’, even if ‘they were not beauties according to European concepts and views’.

Figure 1. Representation of ‘traditional’ garments in a photograph of Baster, Damara, Herero and Nama women, taken to produce classifying, ethnographic knowledge. Source: Koloniales Bildarchiv, Universitätsbibliothek Frankfurt a.M., photograph no. 0030_2022_1830_0096, urn:nbn:de:hebis:30:2-1003504.

Sophie Meritz’s skin might have been fair or dark. She might have brought her physical appearance and looks into play in her dealings with the German state representatives navigating the male-dominated intimate space of a police station. Due to her ‘bastard’ racial status, her clothing could have been an asset in her attempts to make a living and to live a liveable life under colonial rule – and to claim her respectability. But then, skin tone or other physical markers never entered the written conversation around the rape case.

We have already heard about the dismissal of one of the policemen as a result of the libel suit into which the case had evolved. A worse fate befell Sophie Meritz. The district office in Bethanie punished her with six months of imprisonment with forced labour for having knowingly made false accusations.Footnote 59 The severity of her sentence is again indicative of the paramountcy of white male reputation and honour that governed decision making in the police force. Her suspected defamatory lie – of which she had been guilty from the outset based on racist prejudice – weighed extremely heavily in the colonial moral economy. It is difficult to compare the different forms of transgressions and their corresponding punishments since colonial penal practices were so erratic and inconsistent (Schröder Reference Schröder1997; Zollmann Reference Zollmann2010: 107–46). But, as the length of her imprisonment demonstrates, the ‘crime’ of slandering the colonial state or one of its institutions was a particularly serious one.

Gossip, rumours and domestic labour

Yet lies, half-truths and gossip, like the ones of which Meritz and Geffke had been accused, were part and parcel of the social fabric of German South West Africa’s colonial society. As Krista O’Donnell has aptly shown, rumours and collective frights (of African women poisoning their masters, for instance) in this post-genocide settler community were ubiquitous and indicative of settlers’ racial and sexual anxieties (O’Donnell Reference O’Donnell1999). But, as she stresses as well, they also reveal the broader, material underlying issues that were at stake: namely, increasingly tense state–settler relations regarding the question of labour supply, and, linked to this, the question of African reproduction. After the war, labour was short, and the colonial administration put tremendous effort into compelling all colonized subjects into the wage labour economy, while at the same time trying to encourage reproduction (Lerp Reference Lerp2016: 116–40; Zimmerer Reference Zimmerer2001: 176–99). Yet, since African men were forced, or preferred, to work in urban spaces, in the mines and on railway construction sites, there was an even greater lack of domestic and farm hands, who were low paid (if they were paid at all) and had to work hard. Farmers blamed the colonial administration – notably the police – for not supplying them sufficiently. The police, in turn, deemed many of them incapable of treating their ‘natives’ properly. The conflict between settlers and the state evolved around the issue of how much and what kind of corporal chastisement was appropriate and necessary to maintain and control indigenous labour (Muschalek Reference Muschalek2019: 148–57).

With the arrival in the 1910s of growing numbers of white settler women in the colony, and accompanying racialized and moral fears of ‘miscegenation’, settler nervousness over the labour supply gained gendered undertones (Fumanti Reference Fumanti2020; Lindner Reference Lindner2009; Lindner and Lerp Reference Lindner, Lerp, Lindner and Lerp2018). With a white woman present in the intimate space of a settler household, both African women and African men were considered dangerous – as seductresses and sexual predators respectively. In white bachelors’ households, given that often only women (and children) remained to perform domestic work, their male employers were suspected of using these female domestic hands also for sex. This group included the many unmarried policemen whose patriarchal violence and sexual practices came under closer scrutiny – and even more so within the framework of labour shortage. Policemen were supposed to set an example when it came to the ‘proper treatment’ of workers. The Sophie Meritz case and the fight between two German policemen over who got to ‘have’ and ‘use’ her can thus also be interpreted as an economic conflict over the short labour supply (similar to the gendered conflicts in the changing labour market in the Namaqualand mining fields described by Kai Herzog (Reference Herzog2024)), and an ensuing smear campaign insinuating that a female domestic worker came with sexual ‘benefits’, but not for all.

Conclusion: intimate violence and the colonial state

Scholars have shown how ‘sex became a focal point for the fears of white men and the colonial state at various times’ (Bhana et al. Reference Bhana, Morrell, Hearn and Moletsane2007: 133), and how ‘rape scares’ were particularly aimed at disciplining and controlling African men. Yet, rape cases can also reveal the ways in which the state sought to discipline and control white men and black women. While the control of affect and of one’s sexual drive was an important element of bourgeois masculine identity in European metropoles, which extended to the colonies, sexual predation remained a crucial part of the colonizers’ masculinity. From the perspective of the colonizers, the white masculine prerogative needed to be affirmed as the raison d’être of the colonial regime, but disorderly, unauthorized, unprofessional violence had to be controlled for the same reasons. Rape – as distinctively masculine violence – posed a delicate problem to the legitimacy of the colonial state.

The rape of Sophie Meritz had nothing spectacular to it. No political scandal, no public outrage accompanied it (Habermas Reference Habermas2016; Schmidt Reference Schmidt, Naranch and Eley2014). It was also not deployed as a direct means of coercing her or her family into hard labour (Hunt Reference Hunt2008; Mertens Reference Mertens2016), nor was it used as a weapon of war. The rape of Sophie Meritz was a surreptitious, ‘ordinary’ appropriation of an African woman’s body. But, as I have tried to demonstrate in this article, this kind of gendered violence was part of the police’s quotidian activity of state building. Apart from being a story of scheming, intrigue and sociability in a lonely, intimate place, the Meritz case is a story about a group of white men’s ‘right to dispose’ over her body. Policemen’s masculinity and their social status were defined through these questions. As the most visible agents of the state, their individual honour was simultaneously the honour of the state as a whole, and colonial rule was based on them reaffirming their honour in the everyday. Sexual violence was thus inscribed in a discourse that distinguished ‘manly/normal/right’ forms of violence from ‘unmanly/abnormal/wrong’ ones.Footnote 60 Within this distinction, rape was not necessarily one or the other. It could be valued if committed in order to reaffirm one’s adventurous, vigorous, white masculinity. It became a problem to higher echelons when the act displayed a lack of control that harmed the image of the police force and the state. It became a problem to lower echelons when it severed the bonds of loyalty and comradeship. In all cases, and across all ranks, discussions of rape were an occasion to reinforce state authority founded in individual masculine honour – normalizing certain acts of intimate police violence in the process.

Sophie Meritz was not part of that conversation. And yet, only because she decided to press charges and only because she gave a detailed statement that forced colonial officials to justify their actions was I able to recover this small episode of colonial history from the archives. Her voice – as distorted and mediated as it may be – is not lost to us. And while her decision was exceptional, her experience was certainly not. Her attempt to generate a change in her situation may have to stand for the wider history of quotidian sexual violence in the German colonial context: ‘I did not want to go on with [this].’Footnote 61

Acknowledgements

This is a substantially revised version of an article previously published in French in 2018 in the Revue du Vingtième Siècle. I am particularly grateful to the reviewers whose comments helped me shift the focus towards experiences of African women. All shortcomings and mistakes are, of course, my own.

Marie A. Muschalek is assistant professor in the History Department at the University of Basel. She is the author of Violence as Usual (Cornell University Press, 2019).