INTRODUCTION

In 1978, an ‘open-door’ policy was adopted in China, which gradually transformed the planned economy system operating in China for 30 years into a market economy system. In order to support this transformation of the economic system, China joined a series of international conventions and treaties for intellectual property rights (IPR) protection and established its own IPR legal system. China signed the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) Convention in 1980, and on December 11, 2001, China was accepted as a member of the World Trade Organization (WTO). As a compulsory requirement for becoming a member of the WTO, China had to improve its IPR system to comply with the minimum standards of the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) (Keupp, Beckenbauer, & Gassmann, Reference Keupp, Beckenbauer and Gassmann2009; Li & Yu, Reference Li and Yu2015; Lin, Reference Lin2017). Patent Laws, Trademark Laws, and Copyright Laws were all revised, and several other IPR-related laws and regulations were issued during this period. Improvements to Chinese IPR laws during this period were to satisfy the TRIPS Agreement, as well as to meet other international standards (Alimov, Reference Alimov2019; Gao, Reference Gao2008; Zimmerman, Reference Zimmerman2013).

The IPR laws in China have been revised four times over the last three decades: in the early 1990s, in the early 2000s, around 2008, and after 2019. However, the quality of IPR protection in China is still a contentious topic. One group of scholars posits that, after years of development and law revisions, IPR protection in China has been greatly improved, that differences between China and other developed economies will be narrowed down further (Awokuse & Yin, Reference Awokuse and Yin2010; Wang, Reference Wang2004), and that China has undergone impressive development in protecting IPR, given its short IPR development history (Berrell & Wrathall, Reference Berrell and Wrathall2006).

These scholars consider that the development of the Chinese IPR system has been strongly affected by the WTO and TRIPS Agreements (Papageorgiadis & McDonald, Reference Papageorgiadis and McDonald2018), the latter of which holds a relatively high standard of protection of IPR, and can stimulate creativity and innovation, attract foreign investment, and encourage technology transfer. Most importantly, the TRIPS Agreement strengthens IPR protection, a necessary condition for a developing country (like China) to become a member of the WTO and gain freer access to the global economy (Helfer, Reference Helfer2004; Lai, Maskus, & Yang, Reference Lai, Maskus and Yang2020). Gao (Reference Gao2008) observed that the numerous efforts that were made to improve the IPR protection in China around 2001, when China joined the WTO, have resulted in significant progress toward creating a ‘modern, transparent, and effective’ IPR system, which not only meets requirements of the TRIPS Agreement, but also helps China to integrate with global economies when, in fact, most countries at an early stage of economic development would normally choose to adopt a less strict IPR protection regime (Peng, Ahlstrom, Carraher, & Shi, Reference Peng, Ahlstrom, Carraher and Shi2017a). A stronger IPR protection system would then be adopted at a later stage of development to encourage domestic innovation (Chu, Cozzi, & Galli, Reference Chu, Cozzi and Galli2014).

However, another group of researchers holds an opposite view regarding the status of IPR protection in China and argues that, although China has established IPR laws that generally meet international standards, weak enforcement of IPR in China remains one of the biggest deficiencies in its IPR system (Cao, Reference Cao2014; Greguras, Reference Greguras2007; Hu & Jefferson, Reference Hu and Jefferson2009; Zimmerman, Reference Zimmerman2013). Some researchers argue that IPR infringement in China is still at a relatively high level (Cao, Reference Cao2014), and that Chinese IPR laws are complex and confusing because IPR are governed by several separate legal regimes (Liu, Reference Liu2010; Wang, Reference Wang2004). They claim that China does not seem to have followed the development pattern of other democratic countries (as Peng et al. [Reference Peng, Ahlstrom, Carraher and Shi2017a, Reference Peng, Ahlstrom, Carraher and Shi2017b] argued instead) due to its one-party rule, and that the Chinese government may use the law subjectively and selectively (Li & Alon, Reference Li and Alon2020).

A possible reason for the contrasting conclusions on the current and future state of IPR in China reported in previous studies could be the different sources used for these studies, often based on economic and business research, news, government reports (e.g., US government statements), or discussed in the context of cultural heritage (Berrell & Wrathall, Reference Berrell and Wrathall2006; Brander, Cui, & Vertinsky, Reference Brander, Cui and Vertinsky2017; Kshetri, Reference Kshetri2009; Li & Alon, Reference Li and Alon2020; Swike, Thompson, & Vasquez, Reference Swike, Thompson and Vasquez2008). But a void in the literature remains about how IPR laws in China have actually been revised and how their enforcement has evolved in connection to the development of its IPR system, using data from local sources. Therefore, the purpose of this article is to analyze how IPR legislation in China has evolved, and how IPR law enforcement in China has changed.

Huang (Reference Huang2017) carried out a comprehensive review of the IPR system development in China and challenges ahead. The review highlighted a patent surge, judicial and legislative efforts to improve IPR protection in China, and important milestones in China's IPR development history, as well as analyzing the possible drivers behind recent patenting surge. Our study further extends Huang's work by analyzing multiple aspects of the IPR system development in China and utilizing extensive up-to-date secondary data published by different government departments in China to provide a comprehensive understanding of IPR protection development in China over the last 30 years, focussing on Patent Law, Trademark Law, and Copyright Law revisions and IPR enforcement.

We start with an overview of the IPR system in China and review each wave of Patent Law, Trademark Law, and Copyright Law revisions. Then, based on Ginarte and Park's index (Reference Ginarte and Park1997), we build a novel five-dimensional assessment scheme (i.e., scope of protection, duration and procedural provisions, enforcement mechanisms, protection strength, and restrictions) to analyze the degree of changes in each of the three IPR law revisions. The first wave of revisions, introduced in the 1990s, somewhat improved the quality of both Patent Law and Trademark Law, partly due to pressure from the US government (Chen & Maxwell, Reference Chen and Maxwell2010; Huang, Reference Huang2017), while revisions carried out up to 2000, which were required to enter the WTO, were more systematic and far-reaching and established a robust foundation for further future development of Chinese IPR legislation. Two revisions carried out after 2008 are believed to have been developed for China's own ambition of improving its indigenous innovation ability (Li & Yu, Reference Li and Yu2015; Shen, Reference Shen2018; Yang & Yen, Reference Yang and Yen2009), in addition to solving remaining problems in the IPR laws. Revisions of Patent Law, Copyright Law, and Trademark Law after 2008 have taken IPR protection in China to a higher level, comparable to international standards.

After reviewing the evolution of Chinese Patent Law, Trademark Law, and Copyright Law, (details on the data are provided in the section ‘Data Availability Statement’, located at the end of the article), we briefly introduce the current dual administrative and judicial tracks in China, then we analyze the enforcement of these three IPR laws from the dual-track system perspectives. Data on IPR enforcement in China suggest strengthening of the system in the last revision, as while the number of cases handled by administrative departments and courts remained at a comparatively low level during the period of 2004–2008, they showed a substantial increase after 2008.

In the final section, we offer a discussion on how the need to comply with the TRIPS requirements has initiated relevant IPR law revisions and reshaped China's IPR regime. We conclude that, after a solid foundation of IPR legislation was established in the period 2000–2007 focusing on ‘implementing TRIPS’, it is the IPR law revisions after 2008 that clearly showed enforcement of stricter IPR laws on both administrative and judicial tracks. The findings of this article not only show that the development of IPR enforcement did not lag behind the improvement of these three IPR laws, but they also suggest that the Chinese government has a strong willingness to improve its IPR system to stimulate innovation capabilities and achieve the goal of economic transformation.

EVOLUTION OF THE IPR SYSTEM IN CHINA

Evolutionary Changes of the Chinese IPR System

The establishment of the Chinese IPR system can be traced back to the end of the Qing Dynasty (1636–1912). However, society at that time was not prepared for such dramatic change to traditional Chinese culture, which is based on public and shared ownership, and this has affected people's views on IPR principles through to recent years (Yang, Reference Yang2003). In 1949, the People's Republic of China (PRC) was established. However, during the first 30 years of establishment, the public ownership system of sole production means was adopted under theories of Marxism, Leninism, and Maoism. This system rejected the development of a market economy and did not provide necessary social and economic conditions for the establishment of an IPR system (Liu, Reference Liu and Liu2015), which became possible only when China adopted an ‘open-door policy’ after 1978 (Liu, Reference Liu and Liu2015; Yang, Reference Yang2003). Adoption of the open-door policy initiated a comprehensive economic reform, which aimed to transform the planned economy into a socialist market economy with ‘Chinese characteristics’ (Hou, Reference Hou2011; Yang, Reference Yang2003).

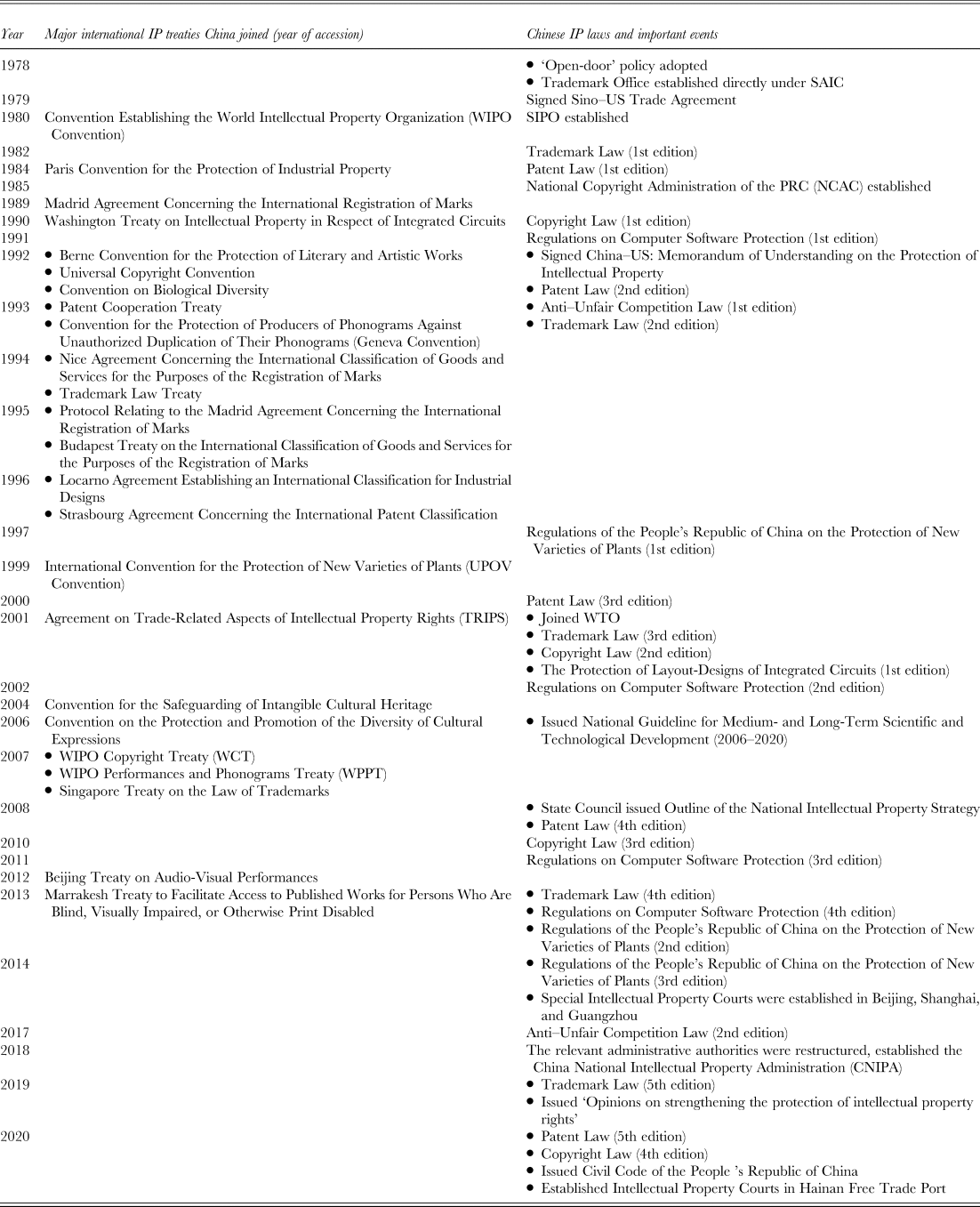

By reviewing milestones in the progress of the Chinese IPR system, it can be noted that, starting with the open-door policy, the Chinese IPR system has experienced five stages of development. First, it established a systematic IPR system during the early 1980s, soon after China and the US initiated a Sino–US Trade Agreement in 1979 and China signed the WIPO Convention in 1980. After that, China undertook a revolutionary transformation with respect to IPR, from a country without any IPR protection to one with a broad and systematic system (Yang, Reference Yang2003). During this period, the first Trademark and Patent Law were enacted in 1982 and 1984, respectively. Second, it revised the Patent and Trademark Laws, enacted Copyright Law, and issued some IPR-related regulations during the early 1990s due to pressure from the US government. China and the US started a negotiation of IPR protection in China in 1991 and entered into the China–US Memorandum of Understanding on the Protection of Intellectual Property (MOU) in 1992 (Kshetri, Reference Kshetri2009), which required China to improve its IPR system. Third, as a compulsory requirement for becoming a member of the WTO, China had to improve its IPR system to comply with the minimum standards of the TRIPS Agreement (Keupp et al., Reference Keupp, Beckenbauer and Gassmann2009; Li & Yu, Reference Li and Yu2015). During this period, China revised its Patent Law (2000), Trademark Law (2001), Copyright Law (2001), and Regulations on Computer Software Protection (2002). Fourth, China improved its Patent Law (2008), Copyright Law (2010), Trademark Law (2013), and regulations after 2008 to comply with the development and innovation goal of the Chinese government. Finally, these three IPR laws were revised further in 2019 and 2020 to further strengthen the IPR protection in China and enhance the country's capacity for independent innovation (Appendix).[Footnote 1]

Evolution of Chinese IPR Laws

Patent Law, Trademark Law, and Copyright Law cover different aspects of IPR, and, in main, protect all phases of innovation activities, from the early stage of developing inventions to the commercialization and diffusion of innovation. The previous section stated that there are four waves of revisions that occurred after the Patent Law, Trademark Law, and Copyright Law were enacted in the early 1980s. We refer to these periods as ‘pre-TRIPS’ (1992–1999), ‘implementing TRIPS’ (2000–2007), ‘post-TRIPS 1 & 2’ (2008–2018 and 2019–present), respectively. In this section, we analyze and provide a deep understanding of how IPR-related laws in China have evolved over time by reviewing each wave of Patent Law, Trademark Law, and Copyright Law revisions in more detail.

Pre-TRIPS (1992–1999): The first wave of revisions

The first wave of revisions that happened during the 1990s only involved Patent Laws and Trademark Laws, which were enacted in the 1980s. The first Copyright Law was enacted in 1990 and therefore had not been revised at this time. The MOU with the US required the Chinese government to revise its Patent Law to include chemical inventions as patentable subject matter and required the inclusion of terms of protection, compulsory licenses, and rights conferred in Patent Law.

The 1993 amendment of Trademark Law in China was based on the Madrid Agreement (Yang & Clarke, Reference Yang and Clarke2005). The 1993 amendment mainly covers changes in three areas: expanding the scope of protection, perfecting the procedures for trademark registration, and strengthening the protection of trademarks by not only broadening the scope of acts that shall be considered an infringement of registered trademarks, but also making more detailed provisions regarding counterfeiting a registered trademark.

The revisions introduced in the 1990s somewhat improved the quality of both Patent Law and Trademark Law, with some researchers arguing that a relatively complete trademark legal system was basically established in China with this revision (He, Reference He2013). The revision also narrowed the gap between Chinese Patent Law and international standards of patent protection, although the improvement was still somewhat limited.

Implementing TRIPS (2000–2007): The second wave of revisions

Joining the WTO has been recognized as an accelerator for improving existent laws of IPR in China (Wang, Reference Wang2004), and it is widely agreed that all relevant Chinese IPR laws revised during this period of time (e.g., Patent Law (2000), Trademark Law (2001), and Copyright Law (2001)) were for the purpose of fulfilling such obligations (Cox & Sepetys, Reference Cox and Sepetys2009; Li & Yu, Reference Li and Yu2015).

Compared with the 1992 amendment of the Patent Law, the 2000 amendment involved changes to 35 provisions, which covered different aspects. The revision not only expanded the scope of protection, perfected procedures of declaring a patent invalid, and addressed confusion between choosing to revoke a patent right or declaring a patent right invalid by keeping only the provisions related to declaring a patent right invalid; but it also granted more power to courts and added pre-litigation provisional measures that a patentee can take to protect their rights. This revision was made to the Patent Law in order to match almost fully what is required in TRIPS (Liu, Reference Liu2002). However, Gao (Reference Gao2008) considered that a patent protection gap still existed between China and other developed countries, and the patent system in China could be further improved.

As with the revisions of Patent Law, the purpose of revising the Trademark Law in 2001 also aimed to prepare China to join the WTO and meet the minimum requirement of TRIPS. The 2001 amendment of the Trademark Law revised 23 articles of the 1993 Trademark Law and added 23 new articles. According to Xiao (Reference Xiao2007), this revision greatly changed the content of the 1993 Trademark Law. This amendment broadened the scope of protection (by adding provisions to protect well-known trademarks) to make it consistent with the provisions of TRIPS and perfected procedures related to application for trademark registration and assignment of registered trademarks, as well as improving the enforcement mechanism by granting more power to courts and administrative departments. Similar to revisions of the Patent Law, some scholars believed that all relevant requirements of TRIPS were introduced, and no substantial differences remained with international trademark rules regarding the overall framework and major system design of the trademark legislation (He, Reference He2013; Jin, Reference Jin2013). However, other scholars found that gaps still existed between the Chinese Trademark Law and TRIPS standards in several aspects, such as the level of protection standards of the Chinese Trademark Law being comparatively low. They argued that more subject areas should be included in the scope of protection content (Wei, Reference Wei2012).

The Copyright Law enacted in 1990 has 56 articles, and the first amendment of the Copyright Law has 60 articles, of which 53 were modified or added. The purpose of revising the Copyright Law was also to meet the minimum requirements of TRIPS. Thus, this amendment was basically modified according to relevant provisions of the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works, TRIPS, and other related international treaties, as well as the development of the internet (Gao, Reference Gao2002). Changes in the Copyright Law can mainly be categorized under five different aspects. The 2001 amendment (1) redefined the protection content and scope in the Copyright Law; (2) specified basic clauses that should be included in the assignment contracts; (3) enhanced the strength of copyright protection provided by relevant administrative departments; (4) modified several provisions so that the copyright protection by judiciary authorities could be further strengthened; and (5) narrowed down the scope of reasonable use of copyright, and revised occasions that do not need permission from the copyright owner. This revision brought a substantial change to Copyright Law in China; not only did it narrow down the gap between the Copyright Law of China and relevant international treaties, but it also improved the level of protection for copyright owners (Gao, Reference Gao2008). It was also important for creating conditions for the development of emerging creative industries in China, such as software design.

Post-TRIPS 1 (2008–2018): The third wave of revisions

In order to achieve the goal of making China an innovative country, the Outline of the National Intellectual Property Strategy issued in 2008 specified that one essential strategic focus was to improve the IPR regime by promptly revising Patent Law, Trademark Law, and Copyright Law and related regulations (State Council, 2008). Another wave of revisions to these laws began, arguably driven by domestic needs for the first time in Chinese IPR regime development history (Wu, Reference Wu2009).

Having already responded to the need to comply with international treaties, the amendment of 2008 was enacted mainly to enhance the level of IPR protection in China and support its aspiration to improve its indigenous innovation capability (Li & Yu, Reference Li and Yu2015; Yang & Yen, Reference Yang and Yen2009). The 2008 amendment modified 36 articles, through revisions made in the 2008 amendment; the scope of patent protection was expanded and redefined (e.g., added provisions related to generic resources and offer to sell), procedural provisions (which are related to applying and transferring patent rights, how to apply for evidence preservation, and stop the infringements before taking legal action) were clarified, the strength of patent protection was enhanced by increasing the fines imposed on patent infringement, clarified and added the actions that administrative departments and the People's Court can take to protect patent, and perfected provisions of compulsory license. Guo (Reference Guo2009) claimed that this amendment further improved patent protection in China and would help to promote scientific and technological progress and economic and social development.

The third revision of the Trademark Law was also mainly aimed at meeting domestic needs and solving some problems that were revealed when practicing Trademark Law following the second revision (He, Reference He2013; Jin, Reference Jin2013). The 2013 amendment of the Trademark Law modified 53 articles of the 2001 Trademark Law, and the total number of articles increased from 64 to 73. The revision of this amendment also expanded the protection scope and added restrictions on the exclusive rights of registered trademarks. Special attention should be paid to improvements that this amendment brought to procedural provisions, enforcement mechanisms, and protection strength. For example, it revised the provision of revisions related to renewal, revoke, transfer, and licensing of registered trademarks; added relevant provisions regarding declaring registered trademarks invalid; strengthened law enforcement of administrative departments; and expanded types of acts that will be considered infringement acts, as well as increasing legal compensation for infringement. After reviewing all the revisions introduced with the 2013 amendment, it was concluded that the main system and basic functions of Trademark Law had been almost completed, and the revisions could help improve economic growth in China (Jin, Reference Jin2013). Unlike the massive revisions to the Patent Law and Trademark Law, only two articles of the Copyright Law were revised in 2010.

Post-TRIPS 2 (2019–present): The fourth wave of revisions

Twelve years after issuing the third revision of Patent Law in 2008, the fourth revision of Patent Law was finally issued in October 2020 after discussing and revising the draft amendments many times. The purpose of this revision was to solve problems that still exist in IPR enforcement, further strengthen IPR protection, and improve domestic independent innovation capabilities in China (Shen, Reference Shen2018). About 30 articles are modified in the 2020 amendment, and revisions improved the Patent Law from different aspects. For example, the scope of protection is expanded by including parts of a product that can be the subject matter for a design patent and the duration of design patents is extended to 15 years; added provisions regarding pharmaceutical patent term extension and established pharmaceutical patent linkage system; statutory damages for patent infringement and punishment for counterfeiting patents are further increased; added an article of limiting abuse patent rights, and further defined the scope of administrative protection for patents.

The Copyright Law was radically revised in 2020 after limited changes were introduced in 2010 when about 49 articles were modified. The scope of protection has been expanded and clearly redefined (e.g., expanded the definition of works to ‘intellectual achievements in the fields of literature, art and science, which are new and original and can be presented in a certain form’), and procedures to enforce the IPR have also been clarified, empowered administrative departments by adding actions that they can take to deal with IPR infringements, expanded the types of acts that will be considered as infringement acts, and increased penalties for copyright infringement (e.g., maximum statutory damages to be paid by infringer increased from RMB 500,000 to RMB 5 million), and added limitations to copyright protection (e.g., teachers and scientific researchers are allowed to adapt, compile, and broadcast a published work for teaching in class or scientific research, instead of only being allowed to translate or reproduce the small amount of copies of published work).

The fourth revision of the Trademark Law is mostly focused on improving the IPR protection from three perspectives: added relevant provisions regarding mala fide trademark registration and application, increased legal compensation for infringement, and clarified actions that the court can take in trademark dispute cases involving goods bearing counterfeit registered trademarks.

In summary, the revisions made in the early 1990s are rather limited and are mainly a response to requirements of the US government. Amendments enacted around the year 2000 for meeting the minimum requirements of TRIPS improved radically the quality of Chinese IPR laws ‒ for example, all Patent Law, Trademark Law, and Copyright Law specified the way to calculate compensation and modified certain provisions so the power of judiciary authorities could be further strengthened. Following a decade of strong technological and economic development, the last two waves of revisions made after 2008 were mainly motivated by the need to improve China's innovation ability and transformation of the economy, and the quality of Patent Law, Trademark Law, and Copyright Law was further enhanced. In order to develop an even clearer understanding of the IPR law revisions in China, the degree of changes of each revision is analyzed in the following section.

An Analysis of the Degree of Changes of Chinese IPR Laws

After reviewing the Patent Law, Trademark Law, and Copyright Law revisions in China, we note that these three IPR laws comprise three main aspects: (1) types of rights and owner of the rights which are protected by law; (2) how to apply, transfer, declare the invalidity of, and reexamine IPR, and (3) IPR protection. Due to the vital role of IPR protection, the laws can be further divided into two aspects: (a) who enforces the IPR protection and (b) how to protect IPR (e.g., the types of acts which can be considered as infringement and punishment for IPR infringement). Furthermore, restrictions of IPR are another important aspect in which to evaluate the quality of IPR laws. The Chinese Patent Law has an individual chapter related to compulsory licenses, which was an important issue raised up by the US government in the 1992 MOU, and some articles in the Copyright and Trademark Laws also put some restrictions on IPR.

Ginarte and Park (Reference Ginarte and Park1997) developed an index of patent system strength that can be used to assess the quality of Patent Laws in a country (Brander et al., Reference Brander, Cui and Vertinsky2017). This index is based on five elements: coverage (i.e., patentability of varied types of products), membership in international treaties, duration of protection, enforcement mechanisms, and restrictions on patent rights. This index is used to score patent systems strength of countries for international comparisons. Building on Ginarte and Park (Reference Ginarte and Park1997)'s index, and considering characteristics of Chinese law, we develop a novel five-dimensional assessment framework to analyze the evolution of IPR laws in China by adding relevant aspects that were not included in Ginarte and Park's index, but are important to analyze the extent of the four revisions of the Patent Law, Trademark Law, and Copyright Law in China, for example, the amount of fines that can be imposed and measures that can be adopted by both administrative and judicial authorities to punish or stop infringements. In this article, a revision of an IPR law is considered improved if: (1) scope of protection is expanded or precisely defined; (2) duration is extended to be consistent with international standards, procedural provisions are simplified or clearly defined regarding application, transferring IPR, declaring an IPR invalid, reexamining, etc.; (3) enforcement mechanisms [Footnote 2] are implemented and more powers are granted to administrative and judicial authorities, or each of their duties is defined clearly; (4) protection strength of IPR[Footnote 3]: type of acts considered to be infringement or actions can be taken to protect the IPR are clearly defined, or punishment for IPR infringers is increased; (5) restrictions on IPR are clearly defined, or consistent with international standards. In the following section, we analyze precisely what changes each revision of Patent Law, Trademark Law, and Copyright Law introduced based on these five aspects.

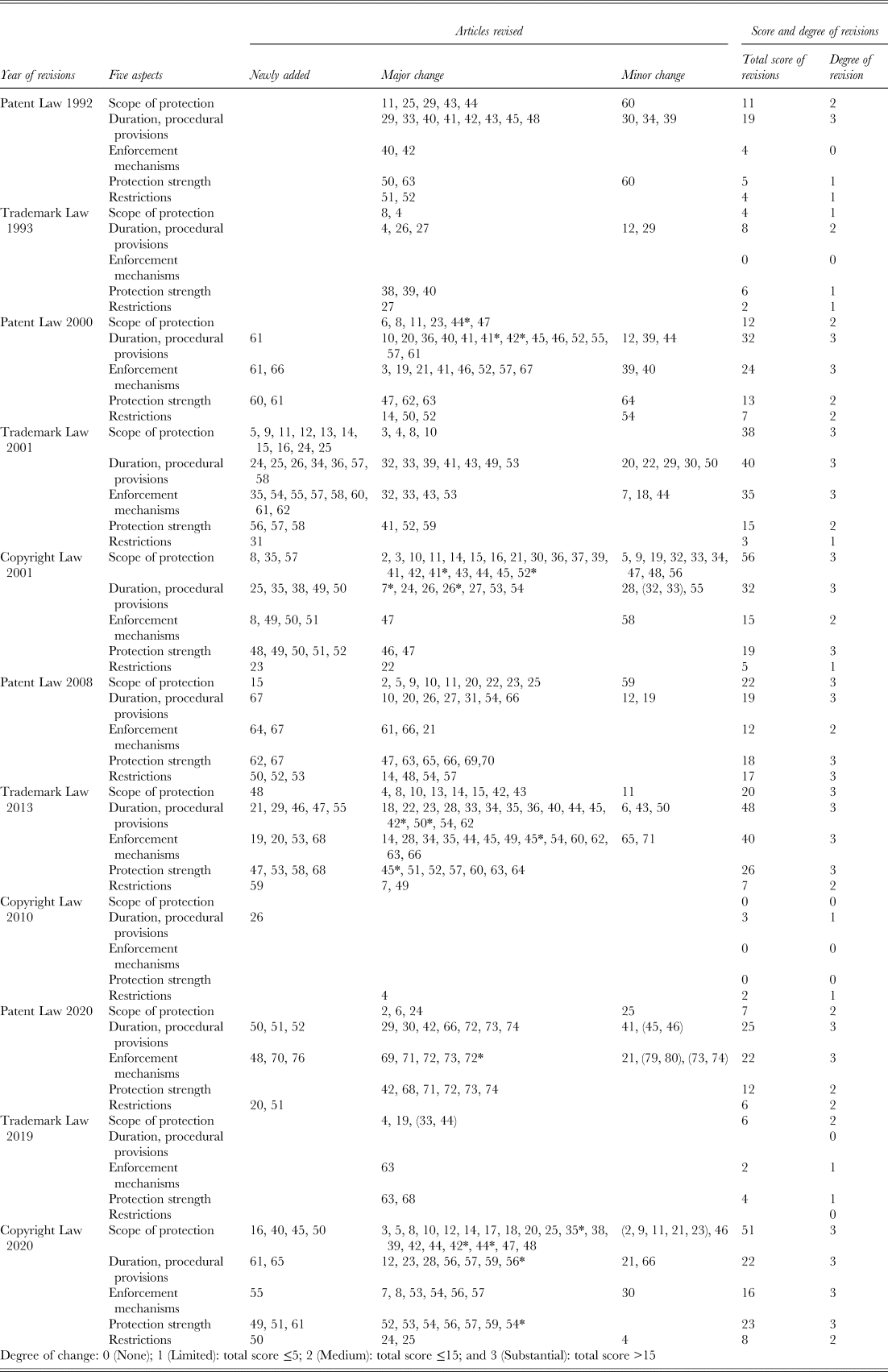

After reviewing the changes introduced with each Patent Law, Trademark Law, and Copyright Law revision, we group all the revisions into three different categories – ‘newly added’, ‘major changes’, and ‘minor changes’ – which are used to measure the degree of revisions of each article in law. ‘Newly added’ means the article is newly created in the revision; ‘major changes’ indicates key information of the article is revised, or part of the article is newly added in the revision, or the original article is deleted from the new revision; ‘minor changes’ means only limited words have been edited, mainly for the purpose of refinement. We assign a different score to those three categories, respectively: newly created articles have a score of 3 points; articles with major revisions have a score of 2; articles with minor revisions have a score of 1. We then count the number of articles that are newly created or have major or minor revisions made to them and calculate the total score of the revision by multiplying a total number of articles that have been revised in that aspect by the degree of revisions. Then we categorize the degree of revisions into four different levels based on the total score of revision: 0 (none) if no revision was introduced; 1 (limited) if the total score is less than 5; 2 (medium) if the total score is between 5 and 14; and 3 (substantial) if the total score is higher than 15. The degrees of change of each law revision in the five various aspects are summarized in Table 1.[Footnote 4]

Table 1. Degree of revisions regarding each article in laws

Note 1: * means this article is deleted from the revision, and the number refers to the article number in the original law. The content of one article may cover more than one aspect; therefore, some articles may appear in more than one place. Some revised articles may not belong to any of these five aspects, so they are not included in the analysis.

Note 2: The total score of revisions = total number of articles that have been revised in that aspect × the degree of revisions. (Newly created articles have 3 points, majorly revised articles have 2 points, and minorly revised articles have 1 point.)

Source: Authors’ own elaboration from several pieces of IPR legislation.

It can be noted that the revisions made in the early 1990s only covered limited aspects, such as expanding the scope of protection; clarifying and simplifying the application, approval, reexamination, and dispute-solving processes; and enhancing the protection strength of Patent Law and Trademark Law. The amendments enacted around the year 2000 for the purpose of complying with the minimum requirements of TRIPS radically improved the quality of written Patent Law, Trademark Law, and Copyright Law, and such quality was further enhanced after 2008.

A ‘DUAL-TRACK’ IPR PROTECTION SYSTEM IN CHINA

An Overview of the ‘Dual-Track’ IPR Protection System in China

The IPR system in China is based on three fundamental aspects: legislative guidance, administrative control, and judicial enforcement (Yang, Reference Yang2003). The previous section shows the legal system to protect IPR was not established until the 1980s; before that, the protection of IPR relied mainly on administrative regulations (Wu, Reference Wu2009). Therefore, a ‘dual-track’ system for IPR protection, comprising both administrative and judicial protection operating in parallel, was formed in China. The joint effort made by administrative departments and judicial organs led to more comprehensive protection for IPR in China (Liu, Reference Liu2005).

Administrative track

The relevant administrative authority (Figure 1) in China has the power to supervise the implementation of laws, as well as to settle IPR-related disputes via administrative departments (Yang & Clarke, Reference Yang and Clarke2005). They also handle the application, examination, and approval of national patents (Yang, Reference Yang2003). The State Intellectual Property Office (SIPO) was the administrative authority responsible for handling China's patent activities and for coordinating foreign-related IPR affairs (SIPO, 2002). Trademark registration and administration were handled by the Trademark Office, while the Trademark Review and Adjudication Board was responsible for handling trademark disputes. Both administrative authorities belonged to the State Administration for Industry and Commerce (SAIC) (SAIC, 2009). In March 2018, ‘the CPC Central Committee on Deepening the Reform of Party and State Institutions’ and ‘the Plan for Deepening the Reform of Party and State Institutions’ were deliberated and adopted at the Third Plenary Session of the 19th CPC Central Committee, ‘the Institutional Reform Plan of the State Council’ was approved by the First Session of the 13th National People's Congress (NPC) (CNIPA, 2018), and the State Administration for Market Regulation (SAMR) was established by integrating the responsibilities of several different administrative departments, for example, SAIC and General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine. (NPC, 2018). In order to use information technology effectively to shorten IP registration time, improve service facilitation, optimize processes, and enhance quality and efficiency of examination, the China National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA) was established as a vice-ministerial-level state agency under the SAMR (CNIPA, 2018). The major responsibilities of CNIPA include formulating and implementing the national intellectual property strategy, protecting intellectual property and IPR, fostering the use of IP, being responsible for the examination, registration, and administrative adjudication of intellectual property (CNIPA, 2018). Patent Office and Trademark Office are responsible for patent and trademark-related administrative activities, respectively, and both belong to the CNIPA. Copyright-related matters are managed by the National Copyright Administration of the PRC (NCAC) and the Copyright Protection Centre of China (CPCC, a subsidiary of NCAC), which is responsible for copyright registration (CPCC, 2017; NCAC, 2017).

Figure 1. Main responsibilities of the major administrative bodies involved in IPR activities Sources: Bosworth and Yang (Reference Bosworth and Yang2000); CNIP. 2021. China National Intellectual Property Administration. [Online] Available from URL: https://www.cnipa.gov.cn/col/col2172/index.html; NCAC. 2018. National Copyright Administration of the PRC. [Online] Available from URL: http://www.ncac.gov.cn/chinacopyright/channels/476.html

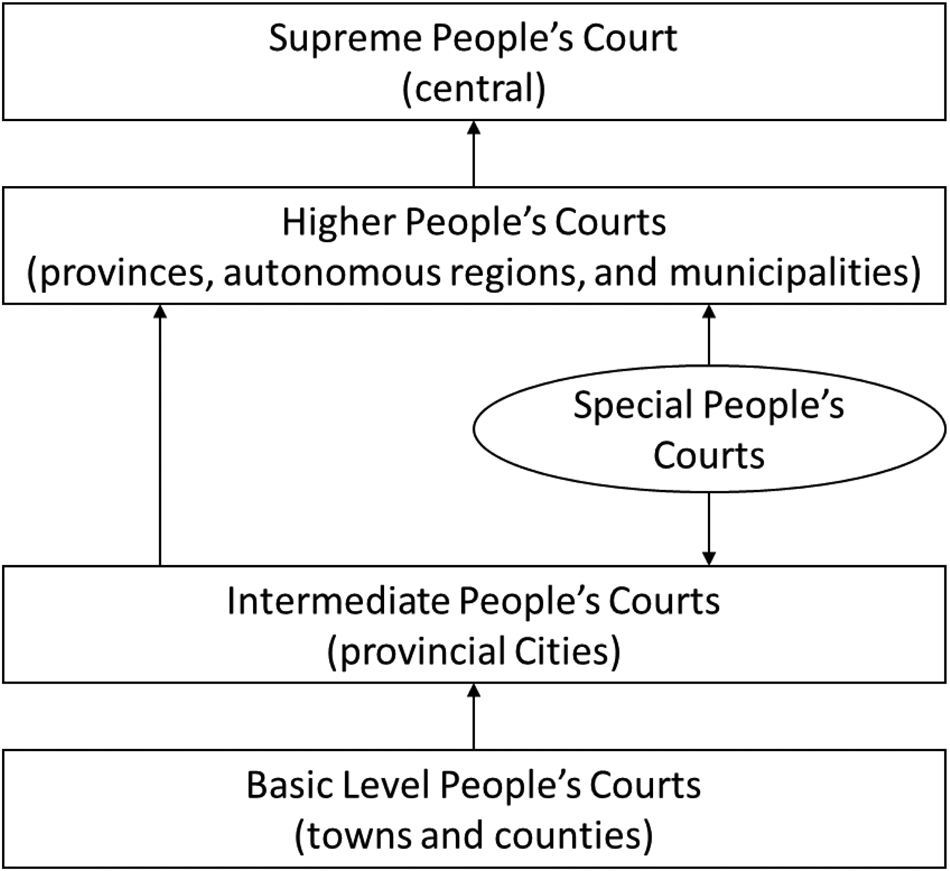

Judicial track

The judicial track is concerned with reinforcing IPR laws and handling infringement and litigation cases. Figure 2 presents an overview of the judicial system in China. According to Civil Procedure Law of the PRC (2012), a Basic Level People's Court shall have jurisdiction as the court of the first instance over civil cases, unless the case has significant influences, or is determined by the Supreme People's Court to be under the jurisdiction of a higher level of court, or is an important foreign-related case. However, since IPR-related cases have certain characteristics such as a high degree of complexity, specialism, and professionalism, which may be beyond the capacity of basic courts to handle, the Supreme People's Court has issued different regulations regarding the jurisdiction of Local People's Courts over IPR civil cases of the first instance.[Footnote 5]

Starting from 1993, intellectual property tribunals were established in the Intermediate and Higher People's Court, and even in the Basic Level People's Court in some cities (e.g., Beijing and Shanghai) (Bosworth & Yang, Reference Bosworth and Yang2000). By 2014, there were 164 Basic Level People's Courts with jurisdiction in general IPR civil cases of the first instance in 20 provinces or municipalities, and most of these courts are in provinces or municipalities with more developed technology and economies, such as Beijing, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Guangdong, and Shanghai[Footnote 6] (The Supreme People's Court of China, 2015). In order to promote the implementation of the national strategy of development driven by innovation, and to further strengthen judicial protection of IPR, Special Intellectual Property Courts were established in Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou by the end of 2014 (The Standing Committee of the NPC, 2014), and a new Intellectual Property Court was established in the Hainan Free Trade Port at the end of 2020. Since 2017, IP tribunals were established in 22 different cities, and the Intellectual Property Tribunal of the Supreme People's Court was also formally inaugurated on January 1, 2019 to hear cases on appeal over patent and other IPR involving professional technologies throughout the country (Bo, Reference Bo2021).

Enforcement of IPR Laws

Having reviewed the ‘dual-track’ IPR system in China and changes made in Patent Law, Trademark Law, and Copyright Law in the early 1990s, around 2000, and after 2008, we now analyze the impact of these changes on IPR enforcement in China.[Footnote 7] In the context of China, some scholars have stated that although IPR laws in China are complete and meet international standards, enforcement is still weak and insufficient (Cao, Reference Cao2014; Zimmerman, Reference Zimmerman2013). Other scholars argued that a weak IPR regime could stimulate technology development via imitation in the early stages of development for emerging countries like China (Chu et al., Reference Chu, Cozzi and Galli2014), and that when its economy becomes sufficiently innovation-driven, China will naturally improve its IPR protection (Peng et al., Reference Peng, Ahlstrom, Carraher and Shi2017a). They also stated that both the Chinese government and firms have realized the importance of improving IPR protection since it can strengthen technology development and sustain economic growth (Peng, Ahlstrom, Carraher, & Shi, Reference Peng, Ahlstrom, Carraher and Shi2017b), and that public awareness of IPR is increasing as the economy and income are growing in China (Chen & Maxwell, Reference Chen and Maxwell2010). Therefore, in this section, we aim to find answers to this debate: whether IPR enforcement development in China is lagging behind the development of Patent Law, Trademark Law, and Copyright Law, or whether it is leading to a co-evolutionary process of relevant IPR laws revision and enforcement.

This section is based on an analysis of multiple official documents (i.e., White Papers on China's Intellectual Property Rights Protection from 1997 to 2020, the Annual Development Report on China's Trademark Strategy from 2008 to 2017, and the National Copyright Statistics from 2000 to 2020) released by SIPO, the Trademark Office of SAIC (known as CNIPA, and Trademark Office of CNIPA after 2018), and the National Copyright Administration of the PRC (NCAC). Under the legislative system of China, the National People's Congress (NPC) and Standing Committee of the NPC enact and amend national law, and State Council issues administrative rules and regulations in accordance with the Constitution and statutes, while departments under State Council may also publish more detailed rules and regulations. The local administrative authorities apply these laws and rules to enforce IPR protection (NPC, 2015). Therefore, in this section, we discuss the influence of IPR-related laws and policies on IPR enforcement based on the ‘dual-track’ system in China.

Administrative track

One of Chinese IPR system's most prominent weaknesses is weak IPR protection enforcement (Brander et al., Reference Brander, Cui and Vertinsky2017; Cao, Reference Cao2014; Greguras, Reference Greguras2007). In this section, we analyze how IPR policies have affected the development of IP protection enforcement, and whether IPR enforcement co-evolves with the Patent Law, Trademark Law, and Copyright Law revisions from the administrative track's perspective.

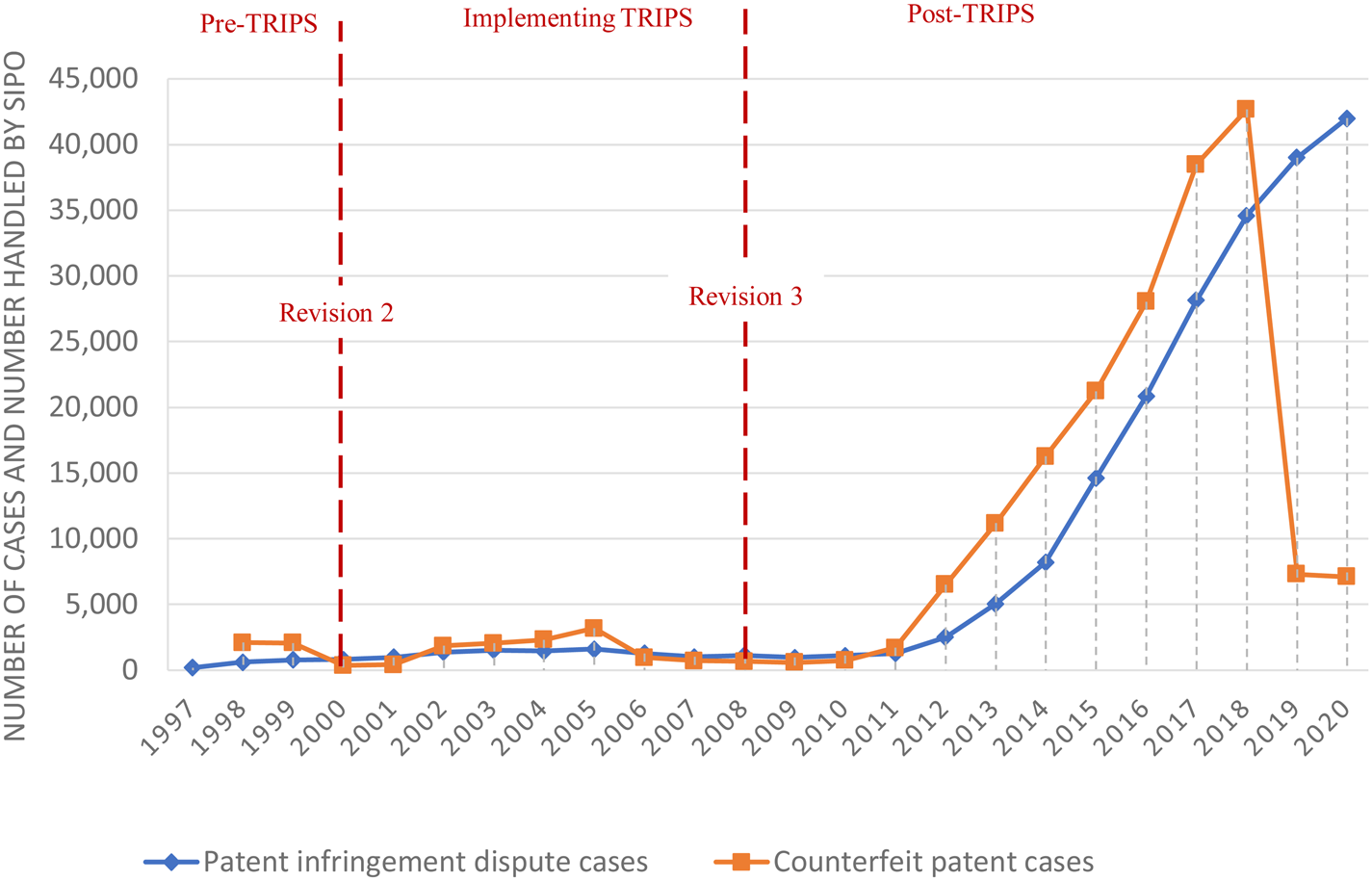

Figure 3 shows the number of patent infringement dispute cases received by CNIPA from 1997 to 2020. It can be noted that there were less than 1,000 cases handled per year during the period of 1998–2001, which increased to around 1,500 per year from 2002 to 2005. This was followed by a sharp increase in 2012 when the number of patent infringement dispute cases received almost doubled from 1,300 in 2011 to 2,500 in 2012. From 2012 to 2020, the average yearly increase rate was 51%, with the number of patent infringement dispute cases handled by CNIPA reaching about 42,000 in 2020. The number of counterfeit patent cases handled by CNIPA started increasing about two years after the Patent Law was modified in each wave of revision, which shows a similar development pattern to the number of patent infringement dispute cases during the same period. However, the number of counterfeit patent cases greatly reduced from 42,679 cases in 2018 to around 7,000 in 2019 and 2020. Relevant administrative authorities also initiated a special campaign in 2019 and 2020, which involved 280,000 law enforcement officers in 2019, but the amount of counterfeit patent cases remained at a low level in both years.

Figure 3. Number of patent infringement dispute cases and number of counterfeit patent cases handled by SIPO/CNIPA from 1997 to 2020 Source: CNIPA. 1997–2020. White papers on China's intellectual property rights protection. Beijing: CNIPA.

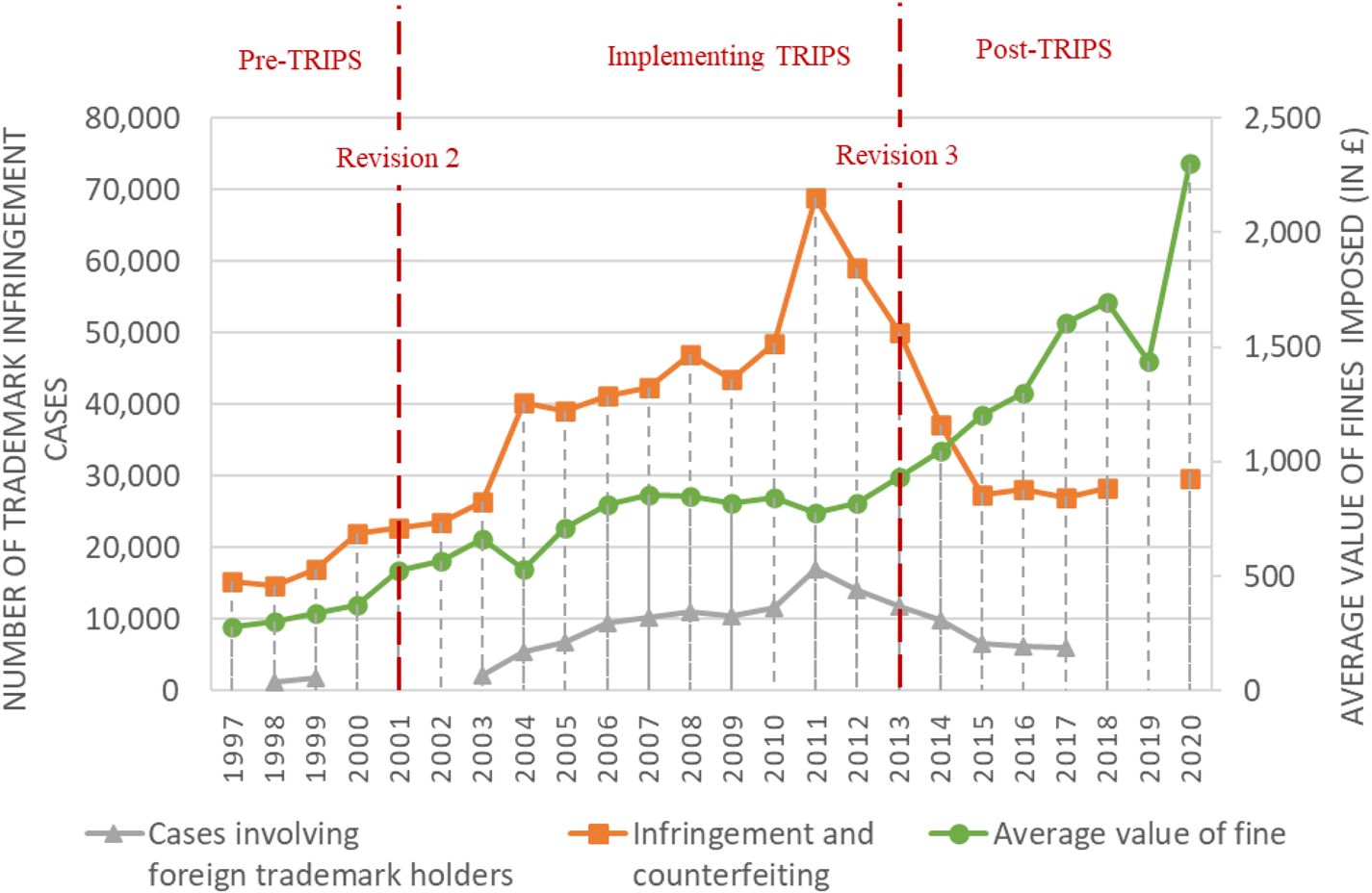

The graph in Figure 4 suggests the enforcement strength of SAMR to protect trademarks resulted in gradual improvement from 1997 to 2004, but that such improvement slowed down during the period of 2005–2010. The most significant growth happened in 2011, although after the number of cases investigated by SAMR started decreasing, it is still higher than before 2003. Such a substantial increase could be attributed to the nine-month special campaign initiated by SAMR, cracking down upon IPR infringement and production and sales of counterfeited goods to enhance protection on trademark rights. The campaign involved nearly four million law enforcement officers checking operating businesses and markets in 2011; however, the number of law enforcement officers dropped to 1.5 million in 2012. After the third wave of Trademark Law revision, it can be noted the IPR enforcement of trademark did not present a similar stage-development pattern. Although the number of cases investigated decreased after 2011, the annual average value of fines imposed in trademark infringement cases increased from £776[Footnote 8] in 2011 to £2,303 in 2020 with a 14% increasing rate. Such an increase could indicate that Trademark Law enforcement continued to strengthen. In addition, it shows a notable increase from 2004 in the number of infringement cases that involved foreign trademark holders, which only constitutes a small proportion of trademark infringement cases.

Figure 4. Number of trademark infringement cases investigated by SAMR and average value of fines imposed by SAMR on trademark infringement cases from 1997 to 2020 Sources: CNIPA. 1998–2020. White papers on China's intellectual property rights protection. Beijing: CNIPA; Trademark Office. 2008–2017. Annual development report on China's trademark strategy. Beijing: China Industry & Commerce Press.

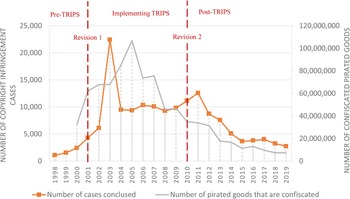

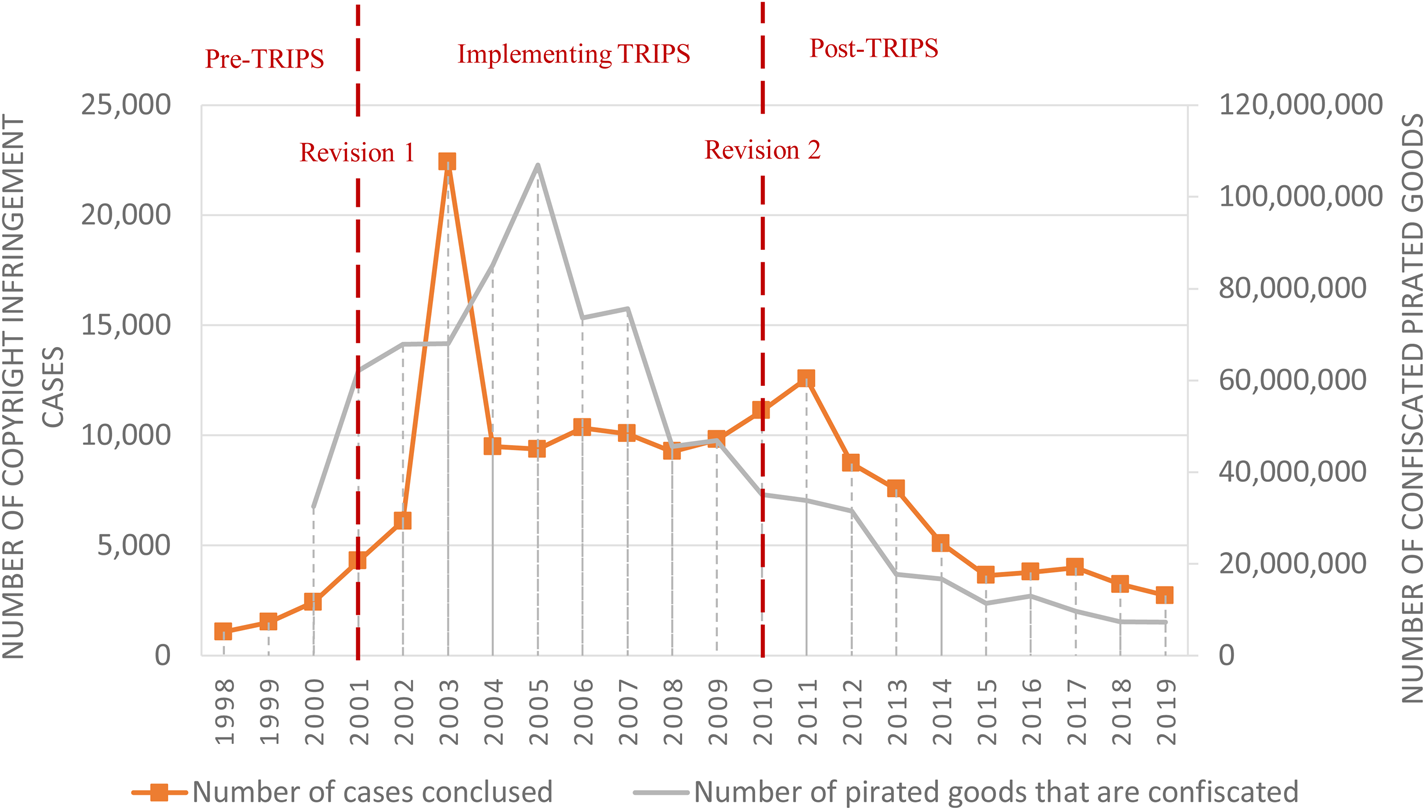

After the Copyright Law was revised in 2001, relevant action outlines and guidance (e.g., ‘Action Outline for Revitalizing the Software Industry (2002–2005)’ and ‘Special Action Plan for the Protection of Intellectual Property Rights’) were issued by the State Council to better enforce Copyright Law, strengthen copyright protection, and stimulate the development of specific industries, such as software. Figure 5 shows the number of copyright infringement cases[Footnote 9] that are handled and the amount of pirated goods (which include books, periodicals, software, audio-visual products, electronic publications, and others) that are confiscated by copyright administrative departments increased greatly since 2001 when Copyright Law was radically revised for the first time. After the number of copyright infringement cases peaked at 22,429 in 2003, it remained at around 10,000 cases from 2004 to 2011 and then decreased to less than 5,000 cases after 2014. The amount of pirated goods that are confiscated by copyright administrative departments increased from 32.5 million in 2000 to 107 million in 2005, the number started decreasing from then, and only 7.3 million pirated goods were confiscated in 2019.

Figure 5. Number of copyright infringement cases handled by copyright administrative departments, and number of confiscated pirated goods from 1998 to 2019 Sources: CNIPA. 1998–2000. White papers on China's intellectual property rights protection. Beijing: CNIPA; National Copyright Administration. 2000–2020. National Copyright statistics 全国版权统计 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.ncac.gov.cn/chinacopyright/channels/12567.shtml

Judicial track

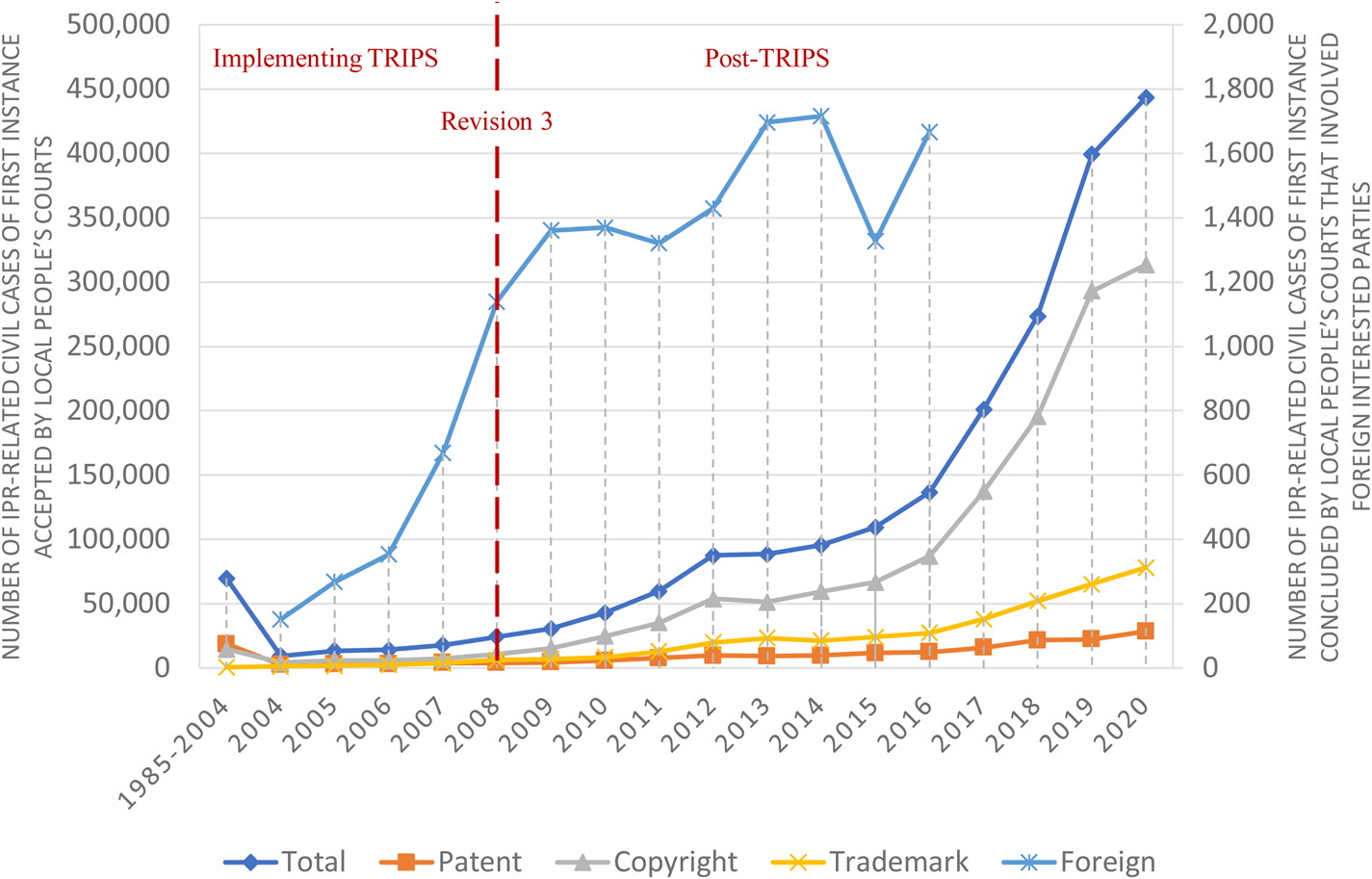

In the ‘dual-track’ system in China, the court also plays an important role in enforcing IPR protections, along with the administrative authorities. In this section, we use the number of IPR-related civil cases and criminal cases handled by courts to analyze the development of IPR enforcement from the judicial track's perspective. Figure 6 shows the number of new IPR-related civil cases of the first instance accepted and concluded (by the origin of interested parties) by Local People's Courts from 2004 to 2020. It can be noted that copyrights present the largest number of cases, followed by trademark and then patent cases. The graph shows that the number of civil cases of the first instance accepted for these three types of IPR continued to increase from 2004 to 2020, and the rate of increase was higher during the period between 2004 and 2012, after which the rate of increase slowed down, but it increased quickly again during the period of 2017–2019. Such increase could be linked to the establishment of Intellectual Property Courts and the IP tribunals. As shown in Figure 6, the number of cases involving foreign interested parties (right-hand scale) constitutes only a very small proportion.

Figure 6. Number of IPR-related civil cases of the first instance accepted by Local People's Courts, and number of IPR-related civil cases of the first instance concluded by Local People's Courts that involved foreign interested parties from 2004 to 2020 Source: CNIPA. 1998–2000. White papers on China's intellectual property rights protection. Beijing: CNIPA.

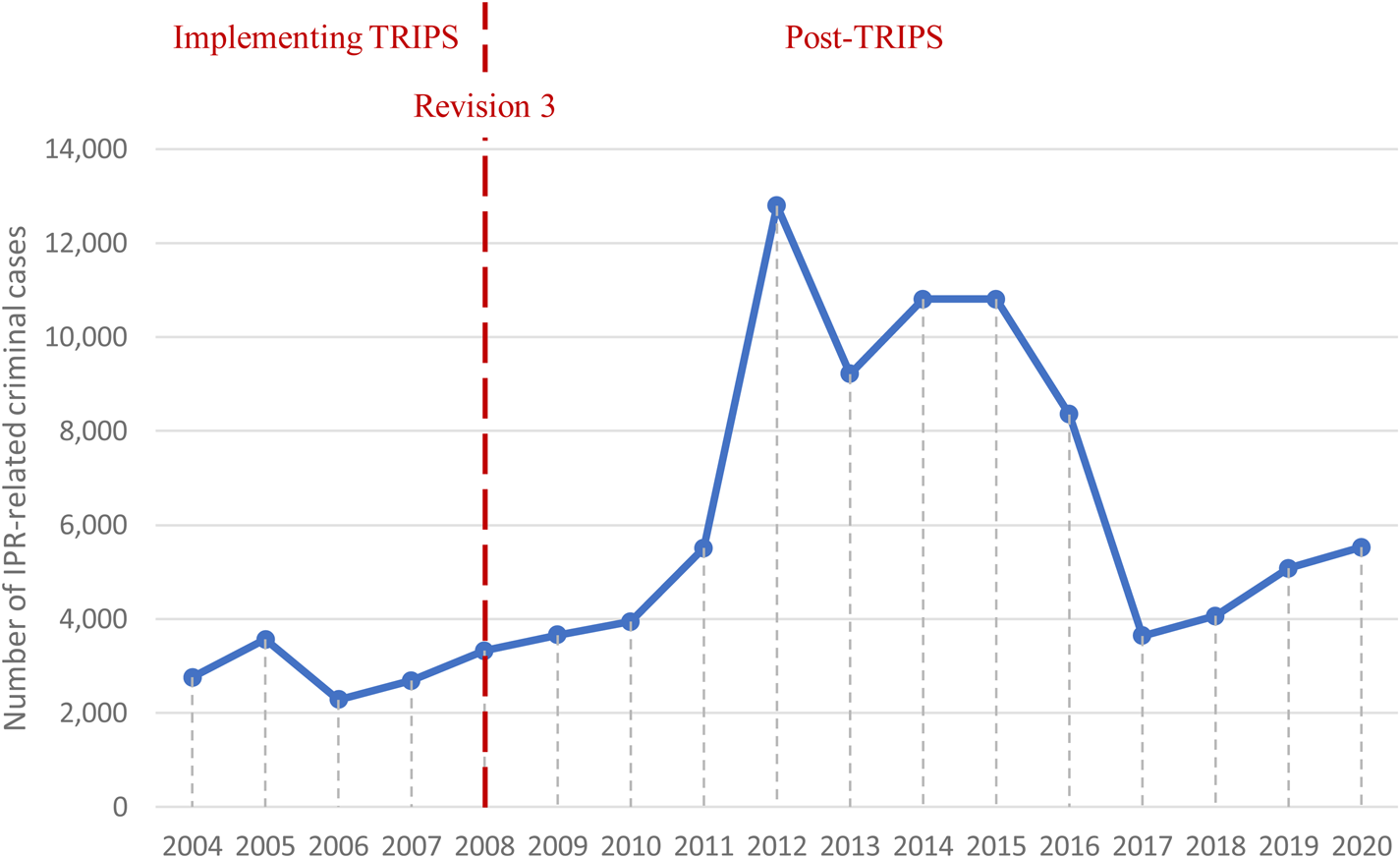

China has been under great pressure from the US to expand the criminalization of its IPR infringement (Liu, Reference Liu2010). Figure 7 presents the number of IPR-related criminal cases of the first instance concluded by Local People's Courts in the period 2004–2020, which indicates the development of criminal enforcement strength in China. The total number of criminal cases concluded increased slowly from 2004 to 2010. This figure then increased to 5,500 in 2011, followed by a sharp increase in 2012 to approximately 13,000 criminal cases. This big increase could be attributed to ‘Opinions on further cracking down the IPR infringement and the production and selling counterfeits and shoddy products’ published by the State Council in January 2012, which emphasized that the government would further strengthen criminal justice and connections between administrative enforcement of law and criminal justice. The number of criminal cases concluded decreased to 3,642 in 2017 and slightly increased to about 5,000 during the period of 2018–2020. Figure 7 shows that, although the number of criminal cases concluded by the court is decreasing since 2012, in recent years, it is still higher than the value before 2011.

Figure 7. Number of IPR-related criminal cases of the first instance concluded by Local People's Courts from 2004–2020 Source: CNIPA. 1998–2000. White papers on China's intellectual property rights protection. Beijing: CNIPA.

To summarize the results in this section, the number of patent infringement dispute cases received by CNIPA and the number of IPR-related civil cases received by courts show similar development patterns as the relevant IPR Law revisions. The amount of IPR-related criminal cases of the first instance concluded by courts also increased from 2004 and peaked in 2012, then started decreasing until 2017 when the number of cases started increasing slowly again. The number of infringement cases handled by SAMR and NCAC shows a similar picture during the second wave of relevant IPR law revisions, after that, the number of infringement cases handled by both departments started decreasing. Although IPR enforcement from SAMR, NCAC, and partly from the judiciary shows a somewhat different picture, altogether the results seem to indicate that the overall IPR enforcement continues to become stronger. The results also reveal that as Patent Law, Trademark Law, and Copyright Law improve in China, the development of IPR enforcement follows the relevant IPR law changes.

DISCUSSION

This article analyzes the evolution of the IPR system in China, delving into revisions of Patent Law, Trademark Law, Copyright Law, and their enforcement. The main contributions of this article are twofold: first, this study provides a detailed and up-to-date analysis of the changes in Patent Law, Trademark Law, Copyright Law, and enforcement over a period of 30 years corresponding to China's entrance into the WTO, until the latest revision introduced in 2020. Second, using a novel five-dimensional assessment scheme and incorporating data from local sources, we provide a comprehensive understanding of Chinese Patent Law, Trademark Law, Copyright Law, and their enforcement, and show how it has intensified considerably alongside significant improvements in relevant IPR laws in China. The findings of this article can strengthen the understanding of China's IPR system and its meaning for protection in China. Thus, it can support scholars, government officials, and managers in making sense of complex and often misunderstood dimensions of the Chinese innovation system.

Grounded in an institutional-based view, Peng (Reference Peng2013) and Peng et al. (Reference Peng, Ahlstrom, Carraher and Shi2017a, Reference Peng, Ahlstrom, Carraher and Shi2017b) claimed that IPR protection in China would improve once the Chinese economy and technology developed to a certain level. However, this view diverges from that of Brander et al. (Reference Brander, Cui and Vertinsky2017), who stated that, although Chinese technological capabilities have increased significantly in the last 15 years, ‘China has a weak internal rule of law, a fragmented governance system, and cultural traditions that favour collective over individual rights’. Our analysis of the Chinese IPR system, based on both written and practiced IPR laws, supports the more positive conclusions of Peng et al. on the quality of IPR protection in China.

With regard to the quality of Chinese Patent Law, Trademark Law, and Copyright Law, we developed a five-dimensional assessment scheme to analyze changes that have been introduced with each amendment. Our analysis shows the revisions made around the year 2000 for purpose of complying with the minimum requirements of TRIPS have led to remarkable improvements to these three IPR laws, and revisions made after 2008 further improved the quality of Patent Law, Trademark Law, and Copyright Law in a process started at the turn of the millennium. The revisions made around the year 2000 not only offered opportunities for China to be part of the global economy, but also established a strong foundation for the future development of the Chinese IPR system. Changes made during this period covered almost all five aspects, as they expanded the scope of protection by including more objects or acts that could be protected by law; simplified procedures related to application, approval, reexamination, and dispute solving; increased the amount of compensation; and authorized more power to both administrative and judiciary authorities for stronger IPR enforcement. They also improved provisions related to IPR protections and restrictions. Thus, while the two waves of revisions made after 2008 were mainly introduced for the purpose of improving China's innovation ability and economic transformation, based on the analysis of revisions on all five aspects, we claim the amendments further enhanced the quality of Chinese Patent Law, Trademark Law, and Copyright Law.

In contrast with scholars who claim that IPR enforcement in China is weak (Brander et al., Reference Brander, Cui and Vertinsky2017; Cao, Reference Cao2014; Greguras, Reference Greguras2007), our study shows the IPR enforcement in China has been improving overall, especially since 2008. Admittedly, most of those earlier studies were conducted prior to the 2008 IPR law revisions, but this supports the need for and value of our study. As for IPR protection enforcement of administrative authorities, the results of our descriptive data analysis show that the number of patent infringement dispute cases received and handled by CNIPA have kept increasing and followed a similar development pattern as the Patent Law revisions. The increasing rate of cases processed has improved greatly, especially since 2012, four years after the third amendment of the Patent Law. Such an increase could be attributed to the fact that the third amendment substantially strengthened administrative enforcement of patent protection. Regarding trademark protection, the number of cases investigated by SAMR continued to increase from 1997 to 2011 but started decreasing afterward. It can be noted the number of cases is still higher than before 2003, and the average value of fines imposed on each trademark infringement case has increased continuously at a rate of 14% since 2011. At the same time, the number of copyright infringement cases that are handled and the amount of pirated goods that are confiscated by copyright administrative departments increased substantially from 2001. Both figures started decreasing after they peaked in 2003 and 2005, respectively.

From the perspective of judicial authorities regarding IPR protection enforcement, among the three types of IPR-related civil cases of the first instance accepted by Local People's Courts, the number of all three types of IPR cases increased from 2004 to 2020. Some scholars have argued that China lacks criminal convictions for IPR infringement (Greguras, Reference Greguras2007; Yang, Sonmez, & Bosworth, Reference Yang, Sonmez and Bosworth2004). However, our analysis shows that over time the number of IPR-related criminal cases has been increasing gradually, and following the last round of revisions in 2008, the number of IPR-related criminal cases has increased greatly. This indicates that the criminal convictions for IPR infringement are becoming more significant. These results support the findings of previous studies, which argue that China is increasing its IPR enforcement from the judicial angle (Liu, Reference Liu2010; Nguyen, Reference Nguyen2010). Furthermore, comparing the decreasing number of infringement cases handled by the Trademark Office and Copyright administrations since the third wave of Trademark Law and Copyright Law revisions, may indicate that courts are playing an increasingly important role in enforcing IPR protection.

Brander et al. (Reference Brander, Cui and Vertinsky2017) interpret these trends as an indication that IPR infringement in China is severe. Li and Alon (Reference Li and Alon2020) argue that China may not be able to improve its IPR system to a level as high as other democratic countries due to its one-party rule political system. We do not share the same concern. Relevant authorities have issued varied policies, initiated several special campaigns to tackle IPR infringements; a substantial increase in the number of trademark infringement cases handled by SAMR and the number of criminal cases handled by courts in 2011 and 2012, respectively, could be attributed to special policies issued by relevant authorities that year. Moreover, in 2008 the State Council issued the ‘Outline of national intellectual property strategy’, which strengthened the importance of IPR protection in China. It can be noted the third and fourth waves of Patent Law, Trademark Law, and Copyright Law revisions and strengthening of IPR enforcement followed the publication of this Outline, thus, in contrast with the arguments of Li and Alon (Reference Li and Alon2020), China appears to continuously improve its IPR system effectively.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, our findings show Patent Law, Trademark Law, Copyright Law, and their enforcement have been greatly enhanced, especially since 2000. This will provide new ground for future discussion of the evolution of these IPR laws in China and provide the basis to investigate further the impact of those changes and enforcement. Defects in the Chinese IPR system that have been discussed in previous studies are being addressed: for example, the development of IPR protection enforcement did not lag behind the improvement of relevant IPR laws. The establishment of special IP courts and increasing number of IP tribunals, restructuring of relevant IP administrative departments, and further revisions of the Patent Law, Trademark Law, and Copyright Law that were issued after 2008, suggests strong willingness by the Chinese government to enhance its IPR system further, to continue to improve IPR laws, and to strengthen IPR enforcement.

APPENDIX

Table A1. Milestones of the evolution of Chinese IP system: From 1978 to present

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in Open Science Framework at ‘https://osf.io/afx94/?view_only=56fe77f7650646e6b409a5384a07e270’, the file name is ‘The evolution of the Chinese IPR system: IPR laws revisions and enforcement’.