One of the last people I interviewed was Robin Bartlett Frazier. By the time we met up in Westminster, Maryland, in 2019, I had been hoping for a chance to speak with Frazier for years, ever since she had been one of the county commissioners who helped make English the official language of Carroll County back in 2013. Compared to the other local governments I studied, that Board of County Commissioners seemed particularly formidable. Whereas the English-only campaigns in the other counties went off the rails (Anne Arundel County), wavered along the way (Queen Anne’s County), or succeeded but later backfired (Frederick County), Frazier and her colleagues voted unanimously to make English official and faced comparatively little internal struggle or external criticism along the way. So, I was curious to hear the perspective of someone who was part of such a smooth language policy campaign. I wondered how she would contextualize Carroll County’s Official English ordinance – would she describe it as a model for the rest of the country, as a steppingstone to state- or national-level policies? Most of my participants did not speak in such sweeping terms, but if anyone might, I thought it would be someone from Carroll County.

As we talked, I realized my hunch was wrong. I asked about language policy at the state and national levels, and she answered ambivalently, then turned the tables by asking me a question of her own and then bringing the conversation back down to local language policy:

flowers: So, do you think that ideally English would be the official language of Maryland and of the United States?

frazier: Mmm, I think most things should be decided at the state level. So, I’m not a big universal, ‘let’s make a law’ (laughs) thinker. So, you know, at the federal level I would say no. Mmm and you know, my mind tells me that there could be some states that have so many Spanish speaking people that, for example, that they might want to have two languages. … You know, I’d have to leave it up to them, but I don’t think Maryland is one of those states. … Because, like I said, it starts snowballing. Where do you stop? (laughs) And it’s very expensive to have documentation, signs, and all kinds of things in different languages.

flowers: Mhmm.

frazier: Howard County has a lot of it. Did you study Howard at all?

frazier: Considering?

flowers: Want to make English the official language.

In response to my initial question, Frazier expresses skepticism toward making English the national official language. Rather than describe her own language policy as a model worth replicating at higher scales, she takes a markedly different approach, by pitching English as a more localized language and language policy as a more localized project. She distances herself from the notion of being “a big universal, ‘let’s make a law’ thinker” by laughing at the very thought.

This interaction sticks with me because Frazier defies the expectation that people want their discourse to seem ever more universal. Through my questioning, I all but invited her to situate the policy in state- or national-level terms, but instead she consistently talks about her language policy as local by design, not just local by necessity or local for now. I had been thinking more about how Carroll County fits into US language policy overall, while she was focused on how Carroll County contrasts with the more multilingual community next door, Howard County.

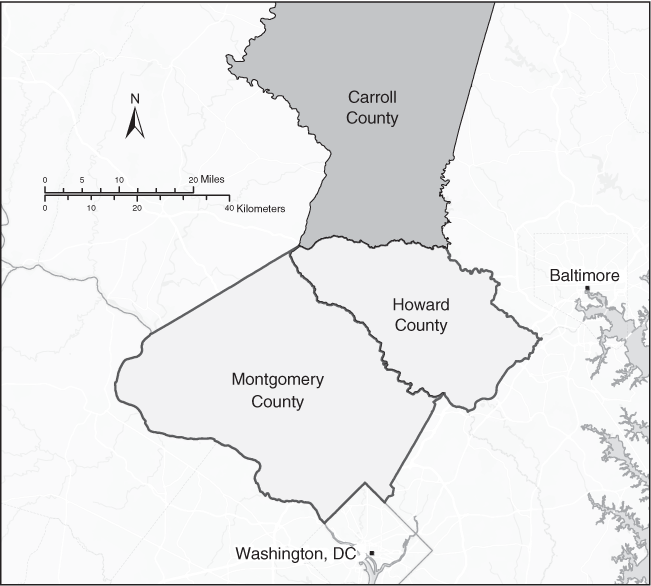

Frazier was not the only one in Carroll County making this kind of argument. Amid some debate over whether Carroll County should keep their English-only policy, the Carroll County Times published an opinion piece a few months after I interviewed Frazier. Christopher Tomlinson of the county’s Republican Central Committee pointed to Montgomery County, another linguistically and racially diverse neighboring county. While Howard County is closer to Baltimore, Montgomery is just southwest, closer to Washington, DC (Figure 3.1). Tomlinson (Reference Tomlinson2020) warned:

Look no further than Montgomery County. According to its county government website, Montgomery translates documents regularly into nearly a dozen languages, including Mandarin, Vietnamese, Spanish, Korean, French, Amharic, Russian, Hindi and Urdu. Heading in a direction completely opposite of Carroll, a 2010 executive order mandated that Montgomery County departments ‘implement plans for removing language bariers’ for limited English proficient individuals and to ‘build a linguistically accessible and culturally competent government.’

For both Tomlinson and Frazier, the best way to explain why their county enacted an English-only policy was to contrast Carroll with its neighbors, rather than to situate Carroll in some larger context.

Figure 3.1 A map showing Carroll County, which passed an English-only policy; two more linguistically and racially diverse nearby counties, Montgomery County and Howard County; and the two major cities in the region, Washington, DC, and Baltimore, Maryland

***

At the same time, not everyone took this localized approach. I witnessed the exact opposite sort of response when I interviewed David Lee (pseudonym), one of the politicians from Anne Arundel County. Like Robin Bartlett Frazier, he supported making English the official language. Unlike in Frazier’s experience, Anne Arundel’s policy was withdrawn before it could come to a vote. Lee invited me to do the interview at his home, and throughout our interview, I would ask him a question that I thought was fairly localized, and he would respond with something much broader about the nation or the globe. For example, at one point I asked him “Why did you think it was important?” as I was gesturing toward a paper copy of his county’s proposed policy; from my perspective, the “it” in my question was that local bill printed on that piece of paper. We were both only a foot or two away from the paper. When Lee answered, however, he framed his beliefs in more global terms, saying “I think the roots come out of my views on Europe” and how, in his view, Europe has too many languages and too much linguistic strife.

After I emailed Lee this interview excerpt during my writing process, he gave me a call. When I saw his number on my phone, I felt a sinking feeling because I assumed he was going to ask me to take it out or add some caveats. After I answered the phone, though, I realized he had called to urge me to add more emphasis on the global, not less. He noted that while the excerpt I quoted is just about language policy, really his focus is not just language but also media, culture, communication, and assimilation more broadly. He also let me know that he saw Official English as one way to prevent Sharia law from taking over.Footnote 1 So, Lee was expanding the scope of this county-level bill in every way. He was taking my question about his county’s policy and framing his answer in much more transnational terms.

This chapter explores the discourse of people like Frazier and Lee. Despite Lee’s desire for English-only policies to have a global reach, Frazier and many of the other people most directly involved in successfully passing English-only policies situate their work more locally, both in terms of how they enact language policies in their own local governments and in terms of how they discuss these policies as harmless community initiatives or as bulwarks against their neighboring counties. If Lee was engaging in what sociolinguist Jan Blommaert (Reference Blommaert2010) has called “upscaling,” then Frazier was doing the reverse, “downscaling.” When studying how people situate their discourse in space and time, or how they decide which scales are relevant in a given situation, most scholarship had focused on upscaling, but not everyone wants their language practices to seem more widespread. Not everyone is invested in the “one nation, one language” ideology that undergirds so many language policy initiatives. Irvine and Gal (Reference Irvine, Gal and Kroskrity2000) describe this ideology as the desire to have “one nation, speaking one language, ruled by one state, within one bounded territory” (p. 63).Footnote 2 While scholars have noted the limitations of this ideology, what is notable in this study is that many US policymakers are not even attempting to achieve “one nation, one language.” These policymakers also tend to stay away from discourse about English as a global language. Where once figures like Thomas Babington Macaulay (1835/Reference Macaulay, Clive and Pinney1972) described English as “preeminent even among the languages of the West,” “likely to become the language of commerce throughout the seas,” and tied to “empire,” those tropes are not what tend to fuel the English-only movement today (pp. 241–242). Instead, I argue that people in this movement find traction in downscaling, or discourse that makes people’s utterances and themselves seem more situated, local, innocuous, or authentic. Because people vary in how they value and attach meaning to different scales, scaling in either direction can be a way to strive for linguistic authority (Gal and Woolard, Reference Gal, Woolard, Gal and Woolard2001; Woolard, Reference Woolard2016).

What really strikes me, and what I will return to toward the end of the chapter, is that Frazier’s modest approach ultimately seems to be not just more common but also more effective at enacting English-only policies than Lee’s more brash approach. I do not think it is a coincidence that the policy proposal in Lee’s county ultimately failed before it could even come up for a vote, while Frazier’s county passed their English-only policy quite easily. People in the English-only movement are often invested in arguing that language policies are not necessarily racist or xenophobic (Bauman and Briggs, Reference Bauman and Briggs2003, p. 302; Dick, Reference Dick2011, p. 50), and downscaling can help create this sense of innocuousness. While adding downscaling to the mix usually makes English-only policies more impervious to criticism, it can also reveal their internal contradictions. When people mix different scaling practices in interaction, the combination occasionally comes across as more dissonant to their interlocutors and may create opportunities for questioning and undoing English-only policies.

The larger point is that upscaling and downscaling are both common, viable, and effective forms of discourse. In making this argument, I hope to decouple the often-assumed link between power and upscaling; the people highlighted in this chapter are powerful by almost any definition of the word: They are white US citizens who use privileged varieties of English, who have in most cases won office as elected officials or led English-only organizations, and who use their positions to write, circulate, and support English-only policies. I hope to show that downscaling can be just as compatible with power as upscaling is.

To make this case, I draw on data from across my study. While in Chapter 2 I take a more chronological approach to telling the story of how people write, revise, and circulate English-only policies, since writing is a process that unfolds over time, upscaling and downscaling are strategies that have truly permeated the whole movement since the beginning. I find that there have not been clear changes over time. What does vary, however, is how different scaling practices fit together and function. Specifically, I identify three kinds of downscaling:

1. Downscaling on its own

2. Complementary upscaling and downscaling

3. Dissonant upscaling and downscaling

In terms of downscaling on its own, I address moments where people downscale their English-only discourse by minimizing the scale and scope of English-only policies, which often has the effect of making them seem harmless and relatable. Next, I address what happens when people jump scales in both directions in the course of a single utterance or interaction. Rather than making English-only policies seem quaint, this move often has the effect of making English-only seem natural and desirable at any scale. While much of the analysis focuses on how downscaling can bolster the English-only movement, I also consider examples of when the juxtaposition of different scaling strategies backfires (from the perspectives of people involved in a given language policy campaign). In such moments, upscaling and downscaling come across as jarring and can create opportunities to question or resist the logic of English-only policies.

From Upscaling to Downscaling

The English-only movement’s penchant for emphasizing the local in local language policy ties into some much larger conversations about what makes some language practices seem more important, more valuable, more powerful, and more legitimate than others. Linguistic anthropologists and linguists such as Susan Gal, Kathryn Woolard, and Monica Heller have led the way in identifying how exactly linguistic authority emerges and evolves in the course of interaction, in terms of both what people say about language and what assumptions remain unspoken. Drawing on her work in Catalonia and Spain, Woolard (Reference Woolard2016) identifies two very different forms of linguistic authority, both of which are relevant to US language policy as well: anonymity and authenticity. The first is the “ideology of anonymity,” which posits that the goal of language is to seem as universal and neutral as possible, as though the speaker could be from anywhere or nowhere (Woolard, Reference Woolard2016, p. 25). In this framework, what matters is “using a common, unmarked public language” (p. 25). This ideal is not necessarily realistic or desirable, of course, but it is what motivates phenomena like newscaster speak, education that focuses on Standard English, accent reduction training, and grammar guides that assume there is one correct way to write. Earlier in her career, Woolard (Reference Woolard1989) observed this ideology of anonymity in the English-only movement, where people were making arguments that English was neutral and universal, whereas other languages were hopelessly tied to particular ethnic enclaves and interests. The other form of linguistic authority Woolard (Reference Woolard2016) identifies is essentially the opposite: the “ideology of authenticity.” In this case, people’s goal is not to seem like they could be from anywhere but instead to seem like they are from somewhere particular (Woolard, Reference Woolard2016, p. 22). Authenticity can be tied to many facets of identity, of course, but Woolard (Reference Woolard2016) points in particular to “the value of a language in its relationship to a particular community” and to how a language “must be perceived as deeply rooted in social and geographic territory in order to have value” (p. 22). Often, both approaches to linguistic authority are in play, and indeed they each can become more meaningful when juxtaposed.

The “one nation, one language” ideology draws much of its power from the fact that both anonymity and authenticity have a part to play. Bonfiglio’s (Reference Bonfiglio2002) study of the rise of the Standard American English dialect epitomizes this duality. In his study of early 1900s language debates in the United States, Bonfiglio (Reference Bonfiglio2002) charts the ways that some white people in the United States began to want their speech to seem at once neutral and specifically white, protestant, and American. The ideologies around this dialect did not develop in a vacuum but were very much about some white people’s desire not to seem Jewish, Catholic, Southern European, or Eastern European.

The issue is that when it comes to language policy and other institutional sorts of discourse, there has been a lot of attention to situations where people try to make their discourse as universal as possible, and only recently more attention is being given to cases where people are more invested in establishing local authenticity or in trying to combine the two forms of linguistic authority. Jan Blommaert’s theory of scale jumping is key here. Over the course of almost twenty years, Blommaert first developed and then continually revised and refined a new approach to scale. Before his too-soon death in 2021, he made a huge impact on how people, including myself, think about how language is situated in space, time, and hierarchies. Blommaert (Reference Blommaert2003) helped popularize the concept of scale in a special issue of the Journal of Sociolinguistics on globalization.

Scale taps into some much older questions about the nature of discourse, power, communicative events, context, and contextualization (Koven, Reference Koven2016, p. 27). While Blommaert has always treated scale as almost entirely a discursive phenomenon, Lemke (Reference Lemke2000) had recently called attention to scales as both discursive and nondiscursive. Specifically, Lemke (Reference Lemke2000) identifies twenty-two timescales relevant to understanding human activity, from the time required for chemical reactions to the school day to the lifespan to geological eras (p. 277). Lemke (Reference Lemke2000) argues that while scales are not merely discursive, determining and negotiating what scales are relevant are also meaning-making practices, for both researchers and participants. Despite these preexisting bodies of work, I do not see Blommaert’s treatment of scale as just a way to reinvent the wheel. In an era of heightened awareness of globalization and localization (Johnstone, Reference Johnstone2016), it makes sense to pay particular attention to how people situate their discourse and themselves in hierarchical spaces and times. Blommaert’s approach offered something new with a more fine-grained way to track how people establish what aspects of context are relevant in a given moment.

Upscaling happens when people respond to an utterance with one that seems situated in a larger and more rhetorically powerful scale (Blommaert, Reference Blommaert2007, Reference Blommaert2010; Irvine, Reference Irvine, Carr and Lempert2016). In a composite scenario Blommaert (Reference Blommaert2007) describes between a student and a tutor, for example, a student says they plan to do their dissertation one way, while the tutor retorts that the university-wide norm is to do dissertations another way (p. 6). In this interaction, Blommaert (Reference Blommaert2007) suggests that the tutor is “invoking practices that have validity beyond the here-and-now – normative validity” (p. 6). This scenario is similar to my interaction with David Lee, discussed earlier, where I was thinking about his county’s policy and he was framing the issue in transatlantic terms. These examples make a certain sense on their own, but the issue is that people may not want to seem more authoritative, or they may not even agree on what counts as authoritative. Even within universities and academic disciplines, for example, people disagree about how dissertations should be written (Prior, Reference Prior1998). Elsewhere, Blommaert, Collins, and Slembrouck (Reference Blommaert, Collins and Slembrouck2005) write, “[a] move from Kenya to the UK is a move from the periphery of the world to one of its centers” (p. 202). In the next sentence, they add, even more bluntly, that “[s]ome spaces are affluent and prestigious, others are not” (p. 203). With any two places, however, whether the UK and Kenya or, in the case of my study, Carroll County and Howard County, or rural Maryland and Washington, DC, or Baltimore, what counts as central or peripheral, affluent or not, prestigious or not, desirable or not will be highly subjective. There is not always clarity or consensus around what counts as what. Scales may be hierarchical, in other words, but those hierarchies are ideological, perspectival, and contingent.

Interventions into theories of scaling have tended to take two forms: exploring upscaling as a more complex phenomenon and turning attention from upscaling to downscaling. In terms of the former, Blommaert (Reference Blommaert2003) himself admits that “it is hard to determine which scale would hierarchically dominate the others” (p. 608). In a discussion of Heller’s (Reference Heller2003) article in the same special issue on globalization, about the local commodification of French in Canadian tourist sites and call centers, he acknowledges that “the direction of value changes again appears to be unpredictable” (p. 613). Blommaert (Reference Blommaert2003) concludes, “we shall need more ethnography” going forward (p. 615) (emphasis in original). Blommaert, Westinen, and Leppänen (Reference Blommaert, Westinen and Leppänen2015) push this self-reflection even further, suggesting that “[t]he 2007 paper [Blommaert, Reference Blommaert2007] was a clumsy and altogether unsuccessful attempt,” especially in light of Westinen’s finding that while scale does matter to her participants, their views on what would even count as high/low or center/periphery are quite dynamic (p. 121).

In a trenchant critique, Canagarajah (Reference Canagarajah2013) describes Blommaert’s (Reference Blommaert2010) model of scale as “static,” “rigid,” and limited because it “doesn’t leave room for agency and maneuver” (p. 156). To address these problems, he argues, “rather than scales shaping people, we have to consider how people invoke scales for their communicative and social objectives” (p. 158). This argument builds on some of Canagarajah’s (Reference Canagarajah2005) earlier work on local language policy. Examining people’s actual discourse is important because their “objectives” are not always going to revolve around upscaling. A few years later, Canagarajah and De Costa (Reference Canagarajah and De Costa2016) turn from theoretical critique to a methodological call: “The specificity of strategies of scaling/rescaling practice needs more analysis. To explore these practices, we need a more negotiated and interactional orientation to data. Such a research orientation could help bring out the contested nature of scales” (p. 8). In my own work, I too find that “a more negotiated and interactional orientation to data” leads to more insight into “the contested nature of scales.” I have found this orientation helpful in revealing how flexible people are in how they talk about language policy. It is this flexibility that allows them to align with or distance themselves from the local, the regional, the national, the transnational, or the global scale at will, in whatever way might make their discourse seem most authoritative in the moment, even if that means taking a different approach than other people in their same social movement.

In addition to complicating the notion of upscaling, there has also been a push to explore downscaling. In the context of literacy education, Stornaiuolo and LeBlanc (Reference Stornaiuolo and LeBlanc2016) argue for further attention to both downscaling and the language ideologies that make downscaling desirable. They define downscaling as “the inverse of upscaling by invoking the local,” which “can be an effective way of redistributing authority or reframing an issue in different spatial or temporal relations” (pp. 272–273). Whether the issue is governmental language policy or literacy education, it is not necessarily a sign of a lack of authority to “rescale the encounter” downward. Rather, downscaling can be a way to alter what counts as authority and who counts as authoritative. Analyzing instances of downscaling can be a nuanced way to track such ideologies as they emerge, sediment, and dissolve in interactions. In the English-only movement, where so much of the conversation revolves around people’s perspectives on the scope of their work, scaling plays a particularly important role.

To explore how scaling practices vary in the English-only movement, I marked instances of scale jumping across my research: interviews, observations, policy texts, archival materials, and other media. I noted utterances where people seemed to make themselves, their language policy, their organization, or the English language seem more national, global, or universal (upscaling) or more local, authentic, or innocuous (downscaling). I also focused on what people were responding to and how their discourse was subsequently taken up. For example, if someone argues for situating a language policy at the state level, it matters whether they are arguing against someone who wanted to situate it at the city level or the national level – the former would be upscaling, the latter would be downscaling. I include myself in this analysis, since research interviews are communicative events too (Briggs, Reference Briggs1986; Koven, Reference Koven2014).

When I designate certain kinds of upscaling and downscaling as “complementary” or “dissonant” in this chapter, those assessments are not about my own personal views, nor are they from the perspective of the people who protested some of these policies (see Chapter 4). Rather, in categorizing my findings in this way, my aim is to represent the perspectives of the people who are in favor of making English the official language. So, when I describe an example in positive terms, I am pointing to the way that utterance has been praised, emulated, or treated as unmarked by other people in the English-only movement. Conversely, when I describe an utterance in more negative terms, I refer to the ways it has been criticized by the people involved.

Downscaling in Action

Over time and across campaigns, organizations, people, and texts, downscaling is common and performs a range of functions, both on its own and in conjunction with upscaling. While I opened the chapter with two contemporary examples, I go into more detail here about instances of downscaling from earlier in the movement’s history, in order to show how this practice has been key to making English-only policies seem more meaningful and desirable since the beginning. I then turn to examples of complementary upscaling and downscaling within the same utterance, to demonstrate how these two kinds of scale jumping can work effectively together. I conclude by addressing instances in which upscaling and downscaling clashed, in order to consider the limits of scale jumping.

The founders and employees of the organizations U.S. English and ProEnglish have talked about scale throughout their history. To be sure, some people affiliated with English-only organizations have taken a more national approach. Senator S. I. Hayakawa, for example, proposed the English Language Amendment to the US Constitution and authored pamphlets with titles like “The English Language Amendment: One Nation … Indivisible?” after becoming Honorary Chairman of U.S. English (Hayakawa, Reference Hayakawa1985). However, many of Hayakawa’s colleagues did not share his approach.

John Tanton in particular took a much different tack in his capacity as the founder of U.S. English and, more than a decade later, ProEnglish. Even before he started U.S. English in 1983, he explicitly called for moving from global to local. In a letter to Harry Haines, a fellow activist, Tanton (Reference Tanton1981, June 30) writes:

If I can offer anything in return, it’s a word of caution against depicting mankind’s problems in a global context where local terms will do. I’ll let my friend and colleague Garrett Hardin carry the burden of the argument in his enclosed writings. The higher up the scale of a dilemma, the easier it is to lose most of us local folks!

While it is unclear in the letter which of “mankind’s problems” they are discussing, or what the favor is “in return” for, what is significant is the general advice to frame issues in “local terms,” because “the higher up the scale…, the easier it is to lose most of us local folks!” This letter is also notable because Tanton had already worked for years with national organizations such as the Sierra Club, Zero Population Growth, and his own Federation for American Immigration Reform, all of which had members in and shaped the politics of every state in the United States. So, it is not obvious that Tanton would count himself as one of “us local folks.” Significantly, Tanton is not talking about whether certain phenomena are local or not but rather about the relative advantages and disadvantages of describing those phenomena as local. His focus is not so much on material understandings of scale (Lemke, Reference Lemke2000) or the local (Pennycook, Reference Pennycook2010) but on the discourse about scale. Tanton may have been purposefully presenting himself as someone with local credibility or trying to establish common ground with Haines as a fellow resident of Petoskey, a small town in Michigan. Either way, he is both calling for and performing downscaling.

The other significant aspect of this letter is the reference to Tanton’s “friend and colleague,” Garrett Hardin. Hardin was a professor of ecology at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and is most known for popularizing the interdisciplinary theory of “The Tragedy of the Commons” (Hardin, Reference Hardin1968). This theory has been taken up in biology, environmental studies, economics, and philosophy and in social movements ranging from environmentalism to anti-immigration activism. Hardin wrote to Tanton at least as early as 1971, initially in the context of the Sierra Club (Hardin, Reference Hardin1971, March 6). Their several decades of correspondence, coupled with the fact that Tanton leans on Hardin to “carry the burden of the argument” for localism, makes it worth briefly examining the nature of those “enclosed writings.”

While the particular texts sent to Haines were not included or named in Tanton’s archived papers, I suspect that they consisted of Hardin’s work on the topic of framing issues locally as opposed to globally. For example, the year before Tanton’s letter, Hardin (Reference Hardin1980) had published an editorial in an academic journal titled “What is a ‘global’ problem?” In this editorial, he argues against global framing using examples of disease:

We never speak of the ‘global mosquito problem’ or the ‘global dysentery problem.’ Why not? Because we recognize that these problems have to be dealt with locally, e.g., by adding Gambusia to local ponds to ingest mosquito larvae or by chlorinating local waters to kill local bacteria. Malaria and dysentery may be ubiquitous problems, but it does no good to label them ‘global,’ because that might discourage local action.

The premise of this argument seems flawed or at least dated, since in the 2020s we have been hearing quite a bit about the global COVID-19 pandemic. Nevertheless, Hardin’s broader points about how “problems have to be dealt with locally” and how global framing might “discourage local action” seem to have resonated with Tanton. Neither Hardin nor Tanton is arguing over whether certain phenomena are local or not but rather about the relative advantages and disadvantages of describing those phenomena as local. For example, Hardin talks about how to “label” and how people “speak,” and Tanton talks about the “terms” of debate and about the risk of “losing” an audience. This attention to discourse, or language about scales, complements the practices discussed in Chapter 2, which hinged more on the material composition and circulation of texts between and around several cities and counties. Both kinds of localism are important to the English-only movement.

Hardin was not just talking about downscaling in his own academic writing; he also consulted for U.S. English during a period when Tanton and his colleagues continued to develop this strategy of downscaling. For example, in 1982 Tanton wrote a letter to Hardin thanking him for his “comments to Gerda [Bikales] on the U.S. English brochure” (Tanton, Reference Tanton1982, November 11). Although not all their promotional materials have been archived, there are clues as to how U.S. English’s discourse evolved during its early years. In a memo to Bikales, Tanton (Reference Tanton1984, March 29) wrote, “I felt it would be very useful to have a third pamphlet, or actually a series of pamphlets, reducing the question down to a state level where it would have more meaning to people than does the national scope of the first pamphlet or the regional view of the second.” This memo is representative of an ongoing pattern, in which Tanton’s colleagues try to frame language policy nationally, only to have him urge them to keep “reducing the question down” to a smaller scale. Downscaling can, in his words, “have more meaning to people” who might be open to supporting English-only policies.

U.S. English not only incorporated Hardin’s and Tanton’s strategies but maintained that approach even after Tanton departed the organization in 1988. Newsletters from the early 1990s almost all feature page-length features with titles like “What’s happening in the states?” and subsections on several different states (in one example: Missouri, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Florida) (U.S. English, 1991, May). One issue of the newsletter included items from cities ranging from Seattle, Washington; to Los Angeles, California; to Harrisburg, Pennsylvania; to Washington, DC (U.S. English, 1991, July). In an article particularly relevant to this study, a later issue covered a debate in the Maryland House of Delegates Judiciary Committee, called “U.S. English Members Help Defeat ‘Linguistic Diversity’ Resolution” (U.S. English, Spring 1993). There are connections between this early period and the twenty-first century, in terms of the same organizations being involved throughout and some of the same people. At the same time, even English-only activists and writers who have never heard of Tanton have long been aware that people care about the local.

The experience of one of my participants, Farrell Keough, illustrates how downscaling can be more persuasive than upscaling. He lives in Frederick, Maryland, and he has worked in business and as a writer. For several years, he ran a site called engagedcitizen.com and had written for local news and commentary sites, like The Tentacle. He supported his county’s 2012 English-only ordinance. I first met Keough in 2015, after he saw one of my flyers and sent me an email. In preparation for our interview, I found and watched a televised appearance he had made at a public hearing earlier in the year, on July 21, 2015, when his government was considering repealing the ordinance. In this appearance, he talked about why he wanted the government to keep the existing English-only policy.

To my surprise, he started his statement by talking about an argument with his wife. He dryly explained, “Before coming here, I decided to consult with an expert. I happen to live with her. We had a rigorous debate. She won … which is common in our household.” Keough went on to spend a few minutes discussing why having English be the official language could save the local government money and could make communication more efficient. His opening sentences had been somewhat cryptic, and I initially assumed that this was an example of a couple in which one half was in favor of an English-only policy and the other was against it, and they had hashed it out, and the English-only argument had won.

When I interviewed Keough, however, I realized something else was going on. He told me that their argument was not about whether to support the 2012 language policy but about why. He had been treating the issue as one of national culture, pride, and sovereignty, whereas she was thinking more in terms of local economic savings and efficiency. So, their argument was not so much about language as about scale. Specifically, they were debating whether the issue was primarily local or national. As we kept talking, he even made fun of himself for initially focusing so much on the national. He explained that he realized he needed to “step back from all the politics” around national language and immigration issues. Then he jokingly did an impression of people who say “foreigners are coming in and taking our jobs,” to which he quickly added, “as they say on South Park.”Footnote 3 Keough decided to “step back” from these large-scale questions of immigration and economics and instead highlight what was going on locally. This sort of “step[ping] back” is an example of downscaling. In his public statement, he talked about his own business experiences. Later, during our interview, he went into more detail and talked about what it was like to get a government permit and how much worse he thought that experience would have been if the people involved had not all used the same language. Notably, although he and his wife initially differed in their approach, her strategy of downscaling ultimately eclipsed his initial impulse to upscale the issue.

While people like Frazier, Lee, Tanton, Hardin, and Keough were thinking in terms of relevant scales (Wortham and Rhodes, Reference Wortham and Rhodes2012), there are other instances that are more about value. In other words, sometimes the issue is not how the local scale seems more relevant than higher scales but about how it seems better than higher scales. The conservative activist Hayden Duke exemplified this kind of downscaling in our interview. At one point, Duke returned to one of my earlier questions about why local governments might be creating language policies, which I had raised in our conversation before the interview officially started. He explained:

You had mentioned localities, and I think the reason Frederick County and other localities are doing what they’re doing, not to justify or otherwise, but just, I think they’re doing what they’re doing as a sense of frustration … There’s absolutely no leadership coming out of Washington. It’s that the federal government is both inept and incompetent and would be more dangerous if they could actually get stuff done.

Here Duke suggests that local governments, including not just his own but “other” ones as well, create language policies out of a sense of “frustration” with higher levels of government. From this perspective, the “federal government” is “inept,” “incompetent,” and potentially “dangerous.” Interestingly, he does not necessarily endorse this perspective, as he makes clear by repeatedly saying “they’re” (instead of “we’re”) and by emphasizing that he is not trying to “justify” this approach. Nevertheless, he does give voice to a certain kind of downscaling, one that situates English in the local scale not because people do not care about higher scales but because they do not like them.

This perspective is in line with recent small-government movements in the United States. Over the past fifteen years, localized, restrictive approaches to language and immigration have become hypervisible, in the form of local laws (Dick, Reference Dick2011) and conservative movements like the Minutemen (Bleeden, Gottschalk-Druschke, and Cintrón, Reference Bleeden, Gottschalk-Druschke, Cintrón, Pallares and Flores-Gonzalez2010) and the Tea Party (Westermeyer, Reference Westermeyer2019). While there is some overlap, Minutemen groups are more explicitly anti-immigration, whereas the Tea Party was about a wider range of conservative and libertarian causes. As Westermeyer (Reference Westermeyer2019) argues in his ethnography of “Local Tea Party groups,” these groups “created the possibility for everyday citizens to produce, materialize, and perform practices and activities” around austerity and small government (p. 9). In particular, several of my participants mentioned the Tea Party unprompted in discussing how they got interested in politics. For people who favor these laws and movements, there is often a belief that the federal government is unlikely to curb immigration and linguistic diversity (either due to reticence or incompetence) and that local groups are better equipped to do so.

While scholars agree that the Minutemen and the Tea Party are important, they disagree about whether such groups are on the fringe or whether they are truly indicative of how the United States operates as a whole. When people do not trust the federal government to accomplish anything, is that a feature of American politics or a bug? Scholars have come to conflicting conclusions. On one hand, Hopkins (Reference Hopkins2018) suggests that most people actually still care more about national issues, perhaps now more than ever. For example, people care more about who is the president compared with who is their mayor or state senator, even though the latter might actually have more of an effect on their everyday life. On the other hand, Grumbach (Reference Grumbach2022) argues that because the federal government is so gridlocked, people do not really expect much to happen at the national level. Instead, the real policymaking happens more locally, because that is the only place where it can happen. There is a need for further research, but I suspect that people’s perspectives can align with both of these theories, depending on how the question is asked. If the question is “do you care about national issues more?”, most people would answer yes. But if the question is “do you think effective policymaking is possible at the national level?” the answer would more likely be maybe. These introductory examples have leaned heavily toward downscaling, yet more often people in the English-only movement combine both.

Complementary Upscaling and Downscaling

While downscaling can happen on its own, people often combine multiple scaling strategies in a single situation. Examples of the same person or text deploying upscaling and downscaling in quick succession are especially common in the most official, public, and legal aspects of English-only discourse. I will discuss two examples, one from language policy texts and one from a public hearing. In terms of written policies, complementary upscaling and downscaling appear in the ordinances passed in Queen Anne’s County, Carroll County, and Frederick County. Queen Anne’s County’s 2012 policy, for example, includes these clauses:

(1) the English language is the common language of Queen Anne’s County, of the State of Maryland and of the United States

…

(5) in today’s society, Queen Anne’s County may also need to protect and preserve the rights of those who speak only the English language to use or obtain governmental programs and benefits; and

(6) the government of Queen Anne’s County can reduce costs and promote efficiency, in its roles as employer and a government accountable to the people, by using the English language in its official actions and activities.

The first clause of the policy sets up a synergy between the local government, the state, and the nation. In other words, the clause suggests that English is rightfully countywide, statewide, and national. The distinction between English and other languages maps onto multiple levels, in an example of fractal recursivity (Irvine and Gal, Reference Irvine, Gal and Kroskrity2000, p. 38). I see this clause as an example of scaling in both directions because the goal is not just to make English seem more local, or more widespread, but to legitimize its official status at a range of levels. Of course, it is worth noting that the scale jumping only goes so far: There is no attempt here to make English the official language of the school, classroom, workplace, home, neighborhood, or street. Downscaling to that degree would invite lawsuits and may not even seem desirable to the policy’s sponsors. Conversely, there is no attempt to frame English as a transnational, global, or spreading language.

As the policy goes on, downscaling comes to eclipse upscaling. The later clauses have nothing to do with promoting the rise and spread of English around the nation, much less around the world. Instead, the focus is on the need to “protect and preserve” monolingual English users’ access to “governmental programs and benefits” in the context of the “County.” The last clause elaborates, by addressing the ways the “County” might benefit financially in its capacity as “employer” and “government.” This policy successfully passed, is still in effect, and shares most of this content with both the ProEnglish template and with the policies from Carroll County and Frederick County.

Situating the English language and the English-only movement in several different scales is not limited to policy texts but also happens in other kinds of discourse. At Carroll County’s December 2012 public hearing, Jesse Tyler of U.S. English made a similar move in a public statement. In his brief statement, he addressed the Board of County Commissioners, as well as a room full of local constituents and a representative of ProEnglish. Tyler began by introducing himself, then introduced U.S. English as “the nation’s oldest and largest non-partisan citizen’s action group dedicated to preserving the unifying role of the English language in the United States. Our organization currently has 1.8 million members nationwide, including 2,500 active members from Maryland and 98 active members from Carroll County.” This statement is an example of complementary upscaling and downscaling because he is not just citing local membership, and not just national membership, but rather listing multiple levels. He argues that U.S. English has an established presence, and is therefore a stakeholder, in the county, the state of Maryland, and the United States. He also emphasizes more than one temporal scale, by highlighting U.S. English’s status as the “oldest” organization of its kind, on one hand, and its current number of “active members,” on the other hand. Of course, it is not clear what counts as “active” or how precise those “2,500” and “1.8 million” numbers are, but he seems less focused on the details than on making his organization and the broader movement seem ubiquitous and inevitable across scales.

These policy and public hearing examples of upscaling and downscaling contrast with those in earlier examples of downscaling alone. On one hand, downscaling can have the effect of making the local seem like a positive exception to higher scales (as in the discourse of Frazier and Duke). On the other hand, when people strategically combine upscaling and downscaling, the effect is often to make the local seem consistent with higher scales. They are both tactics for bolstering the linguistic authority of local English-only policies, but they each rest on a different language ideology about where authority comes from (Woolard, Reference Woolard2016). English, and its monolingual users, can seem authoritative by seeming authentically local or by seeming more like a voice from nowhere, or both.

While from my outsider perspective, these two different strategies might seem at odds with each other, my sense is that the people most immersed in shaping English-only policies have a different take. Even when different sections of the same language policy take different approaches (as in the examples from the Queen Anne’s County policy), these differences do not seem noteworthy to most of my participants, most of the time. So, upscaling and downscaling can not only coexist but mutually thrive. Even people who are critical of English-only policies, ranging from Kevin Waterman and his libertarian public statement and editorial (see Chapter 2) to everyone involved in Frederick County’s repeal campaign (see Chapter 4), did not focus their critiques on questions of scale.

Across all my data, no one expressed anything along the lines of “I can’t figure out if this policy is supposed to be in harmony with or in contrast with state and federal law.” In retrospect, I realize that I even fished, unsuccessfully, for such statements in my interviews. I was curious to see what my participants would make of the scaling strategies at work in things like policy texts and public hearings, and so I asked some version of the following questions in most of the interviews:

Did you get the sense that the people supporting the ordinance were all on the same page about why they supported it, or were there multiple reasons?

Was there ever a time when you disagreed with people who also [supported/were critical of] the ordinance, over the details, or the right way to promote it?

While people answered the questions, no one answered in terms of scale. Usually, then, combining upscaling and downscaling is effective, but not so remarkable that it draws attention to itself.

Occasionally, however, people do notice scale jumping, and it does bother them. In order to address the full range of constraints as well as the affordances of downscaling, in the next section I discuss two moments where people explicitly problematized the practice.

Dissonant Upscaling and Downscaling

Taking a flexible approach to scaling the English language has been largely effective in helping legitimize and enact new English-only policies in Frederick County, Queen Anne’s County, and Carroll County. However, that flexibility can occasionally seem more like dissonance, especially when it comes to the organizations and laws involved. In other words, the idea that English would be a local language and the idea that English would be at once local, statewide, and national are both more popular than the idea that outside activists and lobbyists would shape local language policies. In Frederick County, in particular, some people resented the idea that their language policy existed due in large part to ProEnglish’s and U.S. English’s help. To be sure, some of this resentment came from people who were already against English-only laws: For example, the writers of a progressive blog called Frederick Local Yokel (2015, August 13) wrote a post addressing ProEnglish directly as “you ProEnglish carpetbaggers” (a pointed, historically loaded insult in the United States akin to “interlopers”). However, even people who were open in theory to the idea of English being the official language made this kind of criticism.

The employees of ProEnglish and U.S. English, the two organizations that aspire to shape policy around the country, were particularly attuned to this dissonance. Robert Vandervoort, who was Executive Director of ProEnglish at the time, highlighted this issue during our interview. He recalled:

I mean, we were attacked as being like this outside group, ‘They’re not even FROM Frederick.’ It’s like, ‘Well, we’re a national organization, you know, we’re going to support this wherever it comes up,’ you know, it’d be like telling, you know, the American Red Cross, ‘Oh, well you shouldn’t do a blood drive in Wichita, Kansas, because you’re a Washington, DC-based organization.’ Well, of course the Red Cross is going to be…

Mid-sentence, his office phone rang, and I turned off the recorder as he answered it, and then after the phone call we moved on to other topics. Nevertheless, before he was cut off, he voices the kind of thing he heard from his critics in Frederick, which hinged on the fact that ProEnglish was “not even FROM Frederick.” To point out the potential problems with this kind of attack, he lays out a hypothetical situation in which people make similar complaints about the Red Cross’ humanitarian aid. His point is that not everything can or should be just local – few people would argue that the Red Cross should limit itself to just Washington, DC. Interestingly, Vandervoort seems to use “national” and “Washington, DC-based” interchangeably, or at least he voices them being used interchangeably in the bits of reported speech. Part of the tension he sensed may stem from the fact that people in Frederick, and Maryland more generally, do not see them as synonymous. In the region, DC is not so much a symbol of the nation as it is a big urban city an hour’s drive away. Therefore, people have multiple possible reasons to oppose ProEnglish’s involvement: It can be either because the organization is a symbol of the nation’s capital or because it is a symbol of a relatively unpopular and nearby city. Although Vandervoort had helped ProEnglish sponsor several English-only policies in and beyond Maryland, he seemed frustrated and left the organization a few months after our interview.

Such conflicts were not limited to ProEnglish; there were also differences in scaling strategies between some local politicians and U.S. English. Just after Frederick County’s ordinance passed, the Frederick News-Post (2012, February 26) published an editorial arguing that while the law had passed, “We have conflicting messages here about what this English-only ruling is meant to achieve.” The article goes on to unpack this conflict in more detail, beginning with the perspective of a county official: “On the one hand, Commissioners President Blaine Young has said the ordinance will discourage illegal immigrants from coming to Frederick County. ‘It sets the tone,’ he said.” By connecting English to federal immigration law, Young is shifting the scale from local to national. However, the editorial continues:

On the other, we have what Mauro E. Mujica, chairman and CEO of U.S. English, wrote in a letter responding to an editorial in The (Baltimore) Sun: ‘Making English the official language of the county, state or national government will not have a significant effect on illegal immigration. Granted such legislation may have an impact on immigrants, but the issue of illegal immigration does not belong in the context of the English as official language debate.’

The contrast is stark: While Young, a local politician, is framing English-only as a national issue, the national organization is framing it as local, as disconnected from and “not belong[ing]” to the issue of immigration across national borders.

What the editorial writer(s) had noticed is that while Young was upscaling, by arguing that a local law would have an impact on transnational migration, the national organization was downscaling, by trying to separate the two issues. Later, I asked Mujica about the tension described in this editorial, and his answer heightened the contrast even further. During our interview, I read the above quote from the editorial aloud to him and asked him how it felt when local politicians made comments like Young’s. I was expecting a diplomatic answer that would elide the differences between strategies for the sake of presenting a united, English-only front, but instead, Mujica tied Young’s discourse to what he sees as a broader problem with there being “so many stupid people.” In other words, he seemed to suggest that what Young said was just “stupid” and not worth analyzing in depth. Mujica may have also been picking up on the fact that Young was a particularly polarizing policymaker.

As I touched on in Chapter 2, when speaking at government meetings or with reporters, Young said things about language, race, and immigration that some of my participants considered blunt or even shameless. People in these communities take notice when someone like Young openly celebrates the ability of language policies to marginalize some people more than others. For example, recall that Young expressed a desire to make Frederick “the most unfriendly county in the state of Maryland to illegal aliens” (Anderson, Reference Anderson2011, November 13). When I reiterated my question about whether it bothered him when local politicians said things like that, Mujica said, “It was frustrating in the beginning,” but that he no longer cares. If Young’s discourse plays up the potential reach and racism of local English-only policies, Mujica’s discourse downplays them. Both discursive strategies could potentially work, of course, but Mujica and the journalists in Young’s own community found the dissonance to be too jarring. People like Vandervoort, Young, and Mujica are all in favor of making English the only official language. The tension stems from different understandings of how far language policy should extend and how explicit English-only proponents are willing to be about potential links between English-only policies and racism and xenophobia more generally.

While there is a variety of factors that go into any language policy outcome, it is worth noting that the most striking examples of dissonant upscaling and downscaling came from Frederick County. Of the four Maryland communities where I did fieldwork, Frederick County was the only one to eventually repeal their policy. After Frederick County’s English-only policy passed in 2012, sponsor Blaine Young explored but ultimately dropped out of the race for the governor of the state of Maryland. Even people who respect his work acknowledge that Young’s bold approach had its drawbacks. For example, one of his colleagues remarked to me, “Blaine overplayed his hand on a number of things.” Hayden Duke, the activist quoted in the earlier section, said that people got “Young fatigue” after a while, in large part because he “governed as if he was not going to run again.” In other words, he did not try to make modest, incremental changes; he set out to drastically change the linguistic and demographic landscape of his community to feature more English and fewer immigrants. This “Young fatigue” that Duke references would eventually turn into a backlash so strong that Frederick County repealed this policy in 2015. After being in effect for three years, a group of activists and newly elected local politicians lobbied for the ordinance’s undoing, on the grounds that the English-only policy was bad for the economy, that it was racist, and that it oversimplified language issues, and Chapter 4 is devoted to telling that story.

Meanwhile, David Lee’s home county, Anne Arundel, never got their English-only policy off the ground, while Carroll County’s and Queen Anne’s County’s policies remain comfortably in place. Situating English-only policies as modest local initiatives appears to be a durable legitimizing strategy across people and communities, as seen in the discourse from Robin Bartlett Frazier’s, Hayden Duke’s, and Farrell Keough’s interviews; Jesse Tyler’s public statement at the Carroll County meeting; and the Queen Anne’s policy text. In counties like Carroll and Queen Anne’s, the people who shape language policy have achieved something remarkable: They have successfully made the powerful and controversial English-only movement seem innocuous and even-handed. In terms of linguistic authority, these policymakers have realized the advantages of striving for local “authenticity” instead of or in addition to the ideal of “one nation, one language” or more universal “anonymity.” I turn now to some implications of and remaining questions about downscaling as a common practice in language policy discourse.

What It Means to Go beyond “One Nation, One Language” in Language Policy

The roles of upscaling and downscaling in the English-only movement suggest the need for a complex, dynamic understanding of scale. While many of my examples have come from contemporary English-only campaigns in local governments, these strategies clearly have a longer history: People like Tanton made them key components of the English-only movement from the beginning. Importantly, I find that this strategy exists across genres, modes, people, communities, and times: It truly permeates the English-only movement, even if it can occasionally backfire. Tensions come to light especially when people who work for English-only organizations talk about the policies differently than the politicians and activists they purport to assist. I hope I have offered a new understanding of scaling, as a flexible strategy for legitimation, as well as a new account of the English-only movement, as not necessarily reliant on nationalism. Rather, this language policy movement can thrive even or especially at more localized scales. Downscaling can make language policy seem more innocuous than powerful and more about specific circumstances than broader patterns of racism and xenophobia.

These findings raise questions about how the contemporary policymakers and activists from Maryland, U.S. English, and ProEnglish fit into the history and scope of the English-only movement. While the full extent and effectiveness of downscaling in language policy is a subject for future study, Subtirelu (Reference Subtirelu2013) provides valuable initial insight into this issue. Subtirelu (Reference Subtirelu2013) documents how US members of Congress (national-level politicians) take civic and ethnic nationalist approaches to English-only policies (pp. 59–60). At the same time, the politicians in that study ultimately lost the 2006 debate in question (much to their chagrin, the legal provision about multilingual ballots was renewed for another twenty-five years) (p. 39). In other words, attempts to portray English as a national language may be common, but efforts to make English a local language may actually be more likely to succeed in terms of concrete policy changes. Of course, language policies and ideologies are rarely set in stone. Subtirelu (Reference Subtirelu2013) points out that while the United States still does not have a national language, the nationalist language ideologies live on. Conversely, my participants succeeded in enacting local English-only laws, but one has since been repealed. Nevertheless, there may be a pattern of upscaling gaining more public visibility but downscaling resulting in passing more language policies. Favoring city-, county-, or state-level policies over national policies is common in US history and politics, and English-only activists began capitalizing on that localist impulse.

The strategic benefits of downscaling raise a question. One of the most common queries I get is whether people in the English-only movement really believe in what they say. When they frame English-only policies as local, do they mean it? I admit I have wondered the same question. After all, it may be difficult to see a relationship between how people discuss scale and how they live the rest of their lives. Most of the people discussed in this chapter who deploy localist discourse were born elsewhere and have lived elsewhere, gone away to college, traveled for work, traveled for fun, written news articles or social media posts that had a national or international audience, or helped write laws that were taken up and copied by other lawmakers in other parts of the country. While it is difficult to know for sure, I have two responses to this issue. The discourse analyst in me says that it does not necessarily matter what people believe internally. In other words, from a discourse perspective, what matters is what people say and how, since that is what their interlocutors will hear or read. But of course, it does matter on some level what people really think.

What I can say with confidence is that I see a big difference between how people in the English-only movement discuss their writing practices (as in Chapter 2) and their language ideologies. When it comes to things like ghostwriting and using templates, some English-only policymakers tended to say very different things to me in interviews and in public discourse compared to what they say when they are communicating among themselves. For example, some people interviewed told me they had not collaborated much or at all with ProEnglish, and I later found evidence that they indeed had. Understandably, people may disclose only certain things about their collaborative writing to certain audiences because those writing practices can be highly stigmatized. Policymakers have essentially nothing to gain from saying “I let someone else help write my policies for me.” So, piecing together that story involved a lot more detective work.

In my experience, the same is not true for language ideologies about the scale of the movement. At least among US conservatives, there is no real stigma about supporting English as a national language, state language, or local language, or all of the above, or just not prioritizing language policy at all. When it comes to this topic, I seldom, if ever, noticed outright contradictions between how people in the English-only movements spoke with me and how they spoke to other audiences. When I was piecing together how the English-only movement first formed (Chapter 1), I did not notice contradictions across archival records and media coverage. For example, there was never a situation where someone expressed to me or in public that they think of English-only policies in local terms and then I found evidence elsewhere that they secretly are hard at work on some larger initiative. Instead, I find that many people do not feel constrained to only say certain things on this topic, and many people’s affinity for local government and local policies is real.

The English-only movement’s penchant for both upscaling and downscaling means that there is no simple way to counter their scaling practices with alternative ones. In light of this chapter’s findings, I am increasingly skeptical of attempts to advocate for certain kinds of language policies by advocating for certain kinds of scales. To give one brief example, Tardy (Reference Tardy2011) calls for more work on local language policies and writes that “[a] local view can also afford us a way to imagine possibilities for bottom-up change,” in the form of local language policies that place more value on multilingual writers’ linguistic resources (p. 638). And yet, as Tardy (Reference Tardy2011) herself shows, more monolingual policies can also emerge locally.

In language policy research, there is a sense that “local” and things like “English-only” are opposites, when in fact they can be quite compatible. Instead of taking for granted the ideological valences of the local, future research must approach the concept in a more open-ended way. In terms of implications for language advocacy, there may be problems with English-only policies, but none of those problems would be alleviated if the policies were more or less local. Scaling practices are important to the English-only movement, but not in the sense that if the scaling practices changed, the movement’s overarching goal of elevating English and English users would necessarily change. Upscaling and downscaling may be effective strategies, but they are still just means to an end. In Chapter 4, I examine a case study of people tackling that end more directly, by resisting and rewriting their local English-only policy.