1. Introduction

Certain Semitic languages are characterized by two different ways to form the nominal plural. In Classical Arabic, for example, some nouns and adjectives form the plural by adding a suffix to the singular stem: sg. muʕallim- ‘teacher’ becomes pl. muʕallim-ū-na (nominative), muʕallim-ī-na (oblique); many feminine and some masculine nouns take another suffix, such as sg. maqām- ‘place, station’, pl. maqām-āt-. If the singular stem is marked with the feminine suffix -at-, this suffix is replaced by the plural suffix, as in sg. barak-at- ‘blessing’, pl. barak-āt-. Other nouns and adjectives, on the other hand, form the plural by replacing the stem with a separate, lexically determined, plural stem, as in sg. raǧul- ‘man’, pl. riǧāl-; sg. kitāb- ‘book’, pl. kutub-. Plurals of the first type are referred to as ‘external’ or ‘sound’ plurals, while plurals of the second type are referred to as ‘internal’ or ‘broken’ plurals. As the examples show, broken plurals are not marked by the addition of dedicated plural suffixes. The processes of external and internal plural formation can thus be characterized as concatenative and non-concatenative, respectively. From a morphosyntactic point of view, an additional point of interest is that broken plurals are largely inflected as singulars and, if their referents are non-human, take singular agreement in some languages.

Broken plural formation is highly productive in certain branches of Semitic. Based on its broad distribution throughout the Semitic family, the system is commonly reconstructed for Proto-Semitic (cf. Huehnergard Reference Huehnergard, Huehnergard and Pat-El2019: 59) – as is external pluralization, which is attested in every branch of the family. While certain subfamilies do not productively form broken plurals, various traces of the Proto-Semitic broken plural system have been identified in these languages (Huehnergard Reference Huehnergard and Golomb1987a: 181–8; Wallace Reference Wallace1988). One such trace is a pluralization pattern used for the highly frequent class of *CVCC- nouns. In the Northwest Semitic subgroup, consisting of Ugaritic, Aramaic (including Syriac), Canaanite (including Hebrew), and their closest relatives, these nouns productively form doubly-marked plurals, with an *a infixed between the second and third radical consonant (a form of internal pluralization) and the plural suffixes added (i.e. external pluralization), e.g. *ʕabd- : *ʕabad-ū- ‘servant(s)’. We will refer to this pluralization pattern as *CVCaC-ū-.Footnote 1

The regularity of the sg. *CVCC-, pl. *CVCaC-ū- pattern is generally seen as a shared innovation of the Northwest Semitic subfamily (e.g. Huehnergard Reference Huehnergard and Versteegh2007: 414). When the internal plural system stopped being productive in Proto-Northwest-Semitic, the inherited *CVCaC- plurals belonging to *CVCC- singulars were pleonastically marked with the external plural suffixes. In this way, this pattern at once provides an argument for the phylogenetic unity of Northwest Semitic – somewhat shaky on other grounds – and many examples of old broken plurals (with secondarily added external plural suffixes) in a branch of Semitic where they are otherwise rare or even non-existent, supporting the reconstruction of the broken plural system for Proto-Semitic (cf. Huehnergard Reference Huehnergard, Hoftijzer and van der Kooij1991: 284; Ratcliffe Reference Ratcliffe1998a: 97–8; Gzella Reference Gzella and Weninger2011: 439; Kogan Reference Kogan2015: 228; Noorlander Reference Noorlander2016: 63; but contrast Blau Reference Blau2010: 273).

In this paper, we will question this identification of the *CVCaC-ū- pattern as remnants of old broken plurals. As has been noted, examples of this pluralization pattern occur outside of Northwest Semitic as well, in core vocabulary items which are likely to preserve old morphology. We will therefore argue that the doubly-marked *CVCaC-ū- pattern dates back to Proto-Semitic, removing the motivation for the addition of external plural suffixes to disambiguate unrecognized broken plural forms. Instead, we aim to revive an alternative, phonological explanation for this double marking: that the plural *a is originally an epenthetic vowel. An examination of the origin of the external plural suffixes will lead us to accept the reconstruction of a pre-Proto-Semitic external plural suffix *-w- which occurred between the last consonant of the singular stem and the plural case endings. While it is true that “there is nothing in the phonology of Biblical Hebrew [or other Northwest Semitic languages] which would predict an epenthetic vowel in the environment in which /a/ appears in the [*CVCC-] plurals” (Ratcliffe Reference Ratcliffe1998a: 98), this reconstruction of *-w- does provide such an environment conducive to epenthesis in pre-Proto-Semitic. As the prime example of broken plural formation in Northwest Semitic thus seems to be purely suffixal in origin, we conclude by briefly considering the implications for the history of nominal pluralization in Semitic.

2. How old are *CVCaC-ū- plurals?

Traces of *CVCaC-ū- plurals can be found in several Semitic languages. This is most obvious in the Northwest Semitic languages, where they are considered the regular and only plural form of most *CVCC- singular nouns. The lack of vowel signs in the oldest languages’ writing systems obstructs our view on vowel patterns, but a straightforward picture arises from the data we do have.

First of all, Biblical Hebrew consistently shows an original *a in these plural forms, as can be seen in the well-known examples of méleḵ (< *malk-): məlāḵ-īm (< *malak-ī-ma) ‘king(s)’, malk-ā : məlāḵ-ōṯ (< *malak-āt-) ‘queen(s)’, as well as in sḗp̄er (< *tsipr-) : səp̄ār-īm (< *tsipar-ī-ma) ‘book(s)’ and gṓren (*gurn-) : gŏrān-ōṯ (< *guran-āt-) ‘threshing floor(s)’, etc. In the Aramaic languages these short a-vowels in open syllables have been elided, but they have left their traces. Post-vocalic spirantization of the third root consonant is retained in plural forms such as Biblical Aramaic malḵ-īn ‘kings’ (< *malak-ī-na; sg. méleḵ < *malk- as in Biblical Hebrew) and Syriac alp̄-ē ‘thousands’ (< *ʔalap-ē; sg. alp-ā) and šarḇ-āṯā ‘families’ (< *šarab-āṯā; sg. šarb-ṯā). The majority of the relevant plurals have been analogically reshaped in Syriac, however (Nöldeke Reference Nöldeke1898: § 93). The spelling of the second m in Biblical Aramaic <ʕmmyʔ> ʕaməm-ayyā ‘the peoples’, Syriac <ʕmmʔ> ʕamm-ē, etc. also points to a preceding vowel, as geminates were written with a single letter (as in sg. <ʕmʔ> ʕamm-ā).

The unvocalized epigraphic languages do not provide any information. But for Ugaritic, we are aided by the three different aleph-signs, which indicate the vowel that follows the glottal stop (i is used for syllable-final glottal stop). Thus we have rašm /raʔaš-ī-ma/ (next to rašt /raʔaš-āt-/ and rišt /raʔš-āt-/?) as the plural of riš /raʔš-/ ‘head’, and šant /šVʔan-āt-/ ‘shoes, sandals’ next to a dual šinm /šVʔn-ā/ē-ma/; the dual is regularly formed from the singular stem. Furthermore, there is evidence from syllabic cuneiform transcriptions of Ugaritic, e.g. ḫa-ba-li-ma /ḥabal-ī-ma/ ‘ropes’ (Gzella Reference Gzella and Weninger2011; cf. Classical Arabic, Classical Ethiopic ḥabl- ‘id.’), and [k]a?-ma-ʾa-tu /kamaʔ-āt-u/ ‘truffles’ (Huehnergard Reference Huehnergard1987b).Footnote 2

Outside Northwest Semitic the evidence for *CVCaC-ū- plurals is more scarce. To a certain extent the lack of such forms can be attributed to known factors, such as the loss of short vowels in open syllables in Akkadian (e.g. *ʔab(a?)n-ū- > abnū ‘stones’), the absence of vowels in Ancient South Arabian writing (e.g. ʔrḍt /ʔar(a?)ḍ-āt-/ ‘lands’), and the complex and still poorly understood development of vowels in the Modern South Arabian languages (but now see Dufour Reference Dufour2016). The evidence in Ethiosemitic appears to be limited to Classical Ethiopic kalb ‘dog’, pl. kalab-āt, ḥəlq-at ‘ring’, pl. ḥəlaq-āt, and possibly ṣəḥər-t ‘pot, kettle’, pl. ṣaḥar-āt (Brockelmann Reference Brockelmann1908: 430). Several variant plural forms of these words occur too, but the isolation of the pattern presented here alludes to its antiquity, in particular for a basic noun like kalb.

A far greater number of plurals of the *CVCaC-ū- type can be found in Classical Arabic. Feminine CVCC-at- nouns regularly form their plural by inserting an a-vowel between the second and third radical as well as lengthening the vowel of the suffix, e.g. ḥasr-at- : ḥasar-āt- ‘grief(s)’, kisr-at- : kisar-āt- ‘fragment(s)’, ẓulm-at- : ẓulam-āt- ‘dark place(s)’.Footnote 3 Masculine CVCC- forms generally have a different plural pattern, although one masculine *CVCaC-ū- plural occurs in ʔarḍ- : ʔaraḍ-ū-na ‘land(s)’. While this is the only masculine example, the basic meaning of this isolated noun makes it likely that it preserves an archaic pluralization pattern.

A complicated issue is the relationship between these *CVCaC-ū- plurals and the *CVCaC- broken plurals, which also occur in Classical Ethiopic and Classical Arabic. The commonly accepted view is that the regularity of *CVCaC-ū- plural forms in Northwest Semitic originated in the addition of an external plural marker to *CVCaC- broken plural stems after the collapse of the broken plural system (Ratcliffe Reference Ratcliffe1998b; cf. Brockelmann Reference Brockelmann1908; Greenberg Reference Greenberg and Lukas1955; Fox Reference Fox2003). This is problematic, since we also find the doubly-marked *CVCaC-ū- plurals in Arabic and Ethiopic, where internal plural patterns are very productive and where it would be unnecessary to add a second (external) plural morpheme (cf. Ratcliffe Reference Ratcliffe1998b: 89; Levy Reference Levy1971: 65). Additionally, the broken plural pattern *CVCaC- is restricted to *CVCC-at- singulars in Classical Arabic and *CVCC- singulars in Classical Ethiopic; the stem vowel of the plural is always the same as that of the singular (Ratcliffe Reference Ratcliffe1998b: 116, 136; Fox Reference Fox2003: 160, 213–25, 220).Footnote 4 This makes the *CVCaC- plural pattern look more like a modification of the singular stem than like the complete pattern replacement typical of internal pluralization in Semitic. We should therefore not rule out the possibility that the shoe is on the other foot: these forms derive from old *CVCaC-ū- plurals. These were then reanalysed as broken plurals with a redundant plural suffix, which was subsequently lost. Instead of the doubly-marked *CVCaC-ū- plurals reflecting older *CVCaC- broken plurals, the *CVCaC- broken plurals would then reflect older, doubly-marked *CVCaC-ū- plurals.

In short, *CVCaC-ū- plurals are found in all the branches of the Semitic family tree that are in a position to show them. Adding the observation that the Classical Arabic (especially the masculine example) and Classical Ethiopic instances of *CVCaC-ū- refer to basic concepts and are therefore likely to be ancient, we can conclude that *CVCaC-ū- plurals go back to Proto-West-Semitic at least, and possibly to Proto-Semitic (in which case they were regularly lost in Akkadian).

In a seminal 1955 paper, Joseph Greenberg connected the a-vowel found in these plural forms with similar features throughout the Afro-Asiatic languages. He rejects the thought that “the plural arose from the singular through the development of a Svarabhakti vowels [sic]” (Reference Greenberg and Lukas1955: 199). Greenberg describes five different ways that a marks a plural form in the various languages, labelling the *CVCC- : *CVCaC- correspondence as “intercalation” of a. Although Greenberg's reasoning has been regarded as “a strong morphological argument in favour of a genetic relationship among Afroasiatic languages” (Frajzyngier and Shay Reference Frajzyngier, Shay, Frajzyngier and Shay2012: 10), a-intercalation is only attested in Chadic and Semitic, and its regularity in the Northwest Semitic languages and Classical Arabic (for CVCC-at- nouns) is unparalleled in Chadic. Moreover, this account assumes that *CVCaC-ū- plurals are in fact ancient broken plurals with an added plural suffix, which we have questioned above. Attributing the a-intercalation in the *CVCaC-ū- plurals to an ancient, Proto-Afroasiatic morphological pluralization strategy is thus much more problematic than it is usually taken to be.

Our alternative solution, that the a-vowel is epenthetic in origin, has been proposed before (e.g. Murtonen Reference Murtonen1964). Previously, it was rejected because of the lack of an apt phonological environment for such a change (e.g. Nöldeke Reference Nöldeke1904–05; Ratcliffe Reference Ratcliffe1998b: 140–1, 155). As we will argue, such a suitable environment becomes apparent if we consider the origin of the external plural suffixes.Footnote 5

3. The origin of the *-ū- and *-āt- plural suffixes

The Proto-Semitic external plural suffixes can securely be reconstructed as ‘masculine’ *-ū- (nominative) and *-ī- (oblique) and ‘feminine’ *-āt-u- (nominative) and *-āt-i- (oblique);Footnote 6 cf. Akkadian -ū/-ī, -ātu-m/-āti-m; Classical Arabic -ū-na/-ī-na, -ātu-n/-āti-n; Biblical Hebrew -ī-m, -ōṯ; Aramaic -ī-n, -āṯ-(ā); and Classical Ethiopic -āt.Footnote 7 While the reconstructible presence of mimation, i.e. the absolute state ending *-m, on the ‘feminine’ plural suffix seems clear, it is hard to reconcile the West Semitic ‘masculine’ forms with nunation (*-na) or mimation with the Akkadian forms without a final nasal element. As the presence or absence of mimation or nunation is irrelevant to the present argument, we will simply represent the suffixes as *-ū/ī- and *-āt-u/i-.

The inflection of the external plural suffix brings to mind a number of Proto-Semitic kinship terms. Like the external plural suffix, these forms are characterized by long case vowels in the masculine (before suffixes and in the construct state) and an *-āt- suffix followed by short case vowels with the same quality in the feminine. The reconstructible pairs are *ʔaḫ-ū/ī/ā- ‘brother (nom./gen./acc.)’/*ʔaḫāt-u/i/a- ‘sister’ and *ḥam-ū/ī/ā- ‘husband's father’/*ḥamāt-u/i/a- ‘husband's mother’.Footnote 8 Together with *ʔab-ū/ī/ā- ‘father’, these forms have recently been explained by Aren Wilson-Wright (Reference Wilson-Wright2016) as resulting from a Proto-Semitic sound law already identified by Brockelmann (Reference Brockelmann1908: 186).Footnote 9 This sound law states that wherever a semivowel *w or *y appeared between a preceding consonant and a following vowel, it was lost, while the following vowel was lengthened. The sound law explains many forms derived from so-called hollow and defective roots, which originally had *w or *y as their second or third radical: thus expected forms like *yamwutū ‘they (m.) died’ (from the root mwt), *makwan- ‘place’ (from the root kwn), and *binyat- ‘(act of) building’ (from the root bny) show up in Proto-Semitic as *yamūtū, *makān-, and *bināt- (whence the Biblical Hebrew infinitive construct bənōṯ, see Suchard Reference Suchard2017: 217–8).Footnote 10 Based on the presence of *w as a third radical in a number of derived forms and broken plurals of the kinship terms, Wilson-Wright then reconstructs the pre-Proto-Semitic form of ‘brother’, ‘sister’, ‘husband's father’ and ‘husband's mother’ as *ʔaḫw-u/i/a-, *ʔaḫw-at-u/i/a-, *ḥamw-u/i/a-, and *ḥamw-at-u/i/a-, respectively. The loss of *w between a consonant and a vowel results in the lengthened vowels reconstructible for Proto-Semitic: pPS *ʔaḫw-u/i/a- > PS *ʔaḫ-ū/ī/ā-, pPS *ʔaḫw-at-u/i/a- > PS *ʔaḫāt-u/i/a-, etc.

We propose that the same sound change is responsible for the similar inflection of the external plural suffixes. Using W as a placeholder symbol for either *w or *y, we can hypothesize a pre-Proto-Semitic ‘masculine’ suffix *-W-u/i- (> PS *-ū/ī-) and ‘feminine’ *-W-at-u/i- (> PS *-āt-u/i-). This immediately reveals the constituent parts of these suffixes. In their reconstructed pre-Proto-Semitic form, they both share the same case endings: nominative *-u- and oblique *-i-. The ‘feminine’ is marked by the *-at- suffix, also known from the singular, while the ‘masculine’ is unmarked for gender. And the first element, consisting of the as yet unidentified semivowel *-W-, serves as a plural suffix for both genders.

We are not the first to propose such an origin of the external plural suffixes. The pre-Proto-Semitic reconstruction as *-w-u/i- and *-w-at-u/i-, which changed to *-ū/ī- and *-āt-u/i- through the sound change affecting postconsonantal glides, has been attributed to Zaborski (Reference Zaborski1976) and more clearly put forward by Voigt (Reference Voigt1999).Footnote 11 These scholars adduce supporting evidence from Afroasiatic, where we find an especially clear parallel in Ancient Egyptian. In the hieroglyphic script, which does not usually write vowels, the masculine plural suffix is attested as -w, while the feminine plural is -wt (Allen Reference Allen2013: 60);Footnote 12 as the singular feminine suffix is -t, the feminine plural can be analysed as plural -w- + feminine -t. Thus, ‘brother’ is sn; ‘brothers’ is snw; ‘sister’ is snt; and ‘sisters’ is snwt. Many nouns have given up the use of this plural suffix in Coptic, the last offshoot of Ancient Egyptian, which is written alphabetically. But forms like ⲥⲛⲏ(ⲟ)ⲩ/ⲥⲛⲉ(ⲟ)ⲩ /snē̆u/ ‘brothers’ confirm the semivocalic nature of the suffix. Contrary to some interpretations, Wilson-Wright (Reference Wilson-Wright2016: 27–8) reconstructs the plural suffix as *-w (thus also Voigt Reference Voigt1999: 14) or *-wV; the various preceding vowels that appear in Coptic then belong to the noun stem, not the plural suffix.Footnote 13

The order of the number and gender suffixes in the Egyptian feminine plural is striking. Cross-linguistically, it is normal for nouns to mark gender closer to the stem than number, as gender is an inherent feature of the lexeme while number is inflectional (Greenberg Reference Greenberg and Greenberg1966: 93; Booij Reference Booij, Booij, Lehmann and Mugdan2000: 365–6). In Egyptian, however, we see that the plural suffix -w comes immediately after the noun stem and is followed by the femine suffix -t. The exact parallel in our pre-Proto-Semitic reconstruction *-W-at-u/i- cannot be coincidental.Footnote 14 We may therefore identify our pre-Proto-Semitic glide *-W- with Ancient Egyptian -w and, together with Voigt, reconstruct the pre-Proto-Semitic plural ending as *-w- as well.

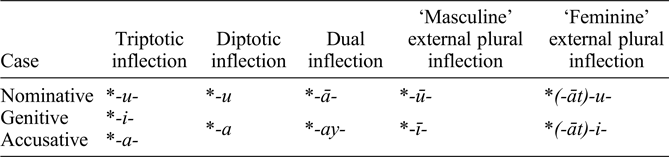

Hasselbach (Reference Hasselbach and Miller2007: 128–9) levels some criticisms against this reconstruction, which we should address. First, in her view, this explanation does not account for the two-case inflection of the plural (nominative/oblique) compared to the three-case (‘triptotic’) inflection of most singulars and broken plurals. The underlying assumption is that the Semitic case endings are unmarked for number and should therefore be used equally for the singular, broken plural, and external plural. In fact, the triptotic inflection is just one of five different inflection classes we can reconstruct for Proto-Semitic (see Table 1; cf. Al-Jallad and Van Putten Reference Van Putten2017: 89)

Table 1 The five inflection classes of Proto-Semitic

The reconstruction of the external plural suffixes advanced here would bring this down to four classes for pre-Proto-Semitic, merging the ‘masculine’ and ‘feminine’ external plural inflections into one external plural class with nominative *-u- and oblique *-i-. While it is striking that most of these endings consist of vowels only and that most inflection classes have *-u- as the nominative ending, these are clearly distinct systems. In fusional languages like those of the Semitic family, we have no more reason to expect singular and plural case endings to resemble each other than in the similarly fusional Indo-European languages (where most singular and plural case endings look completely unrelated). Moreover, it is clear from this overview that three-case inflection is actually the exception, not the rule: of the four or five inflectional classes, only one distinguishes the genitive from the accusative. Thus, we find it unproblematic to reconstruct *-u- and *-i- as the nominative and oblique plural case endings, which happen to resemble the nominative and genitive triptotic case endings, but are functionally distinct.

Hasselbach's second objection is that this explanation depends on the supporting evidence from Afroasiatic, and that *-w- primarily occurs in postvocalic position there, where the elision of postconsonantal glides should not apply. The resemblance to the III-w kinship terms ‘brother’, ‘sister’, and ‘husband's father/mother’, however, leads us to the pre-Proto-Semitic reconstruction as postconsonantal *-W- on internal grounds alone. The Afroasiatic and especially Egyptian evidence then serves to confirm the identification of this unidentified *-W- as the bilabial glide *-w-, but is not essential to the reconstruction. As for the postvocalic or postconsonantal position of this *-w-, it is easy to see how the immense time scales at work in Afroasiatic reconstruction may have played a role here. Either the vowels we find preceding *-w- in the other branches of Afroasiatic could be secondary, or an original, Proto-Afroasiatic vowel could have been lost on the way to Semitic. The reconstruction of postconsonantal *-w- is only assured for a very recent precursor of Proto-Semitic and need not be of Proto-Afroasiatic date by any means. Thus, our internal arguments for the reconstruction *-W(-at)-u/i- make Voigt's account quite compelling, despite Hasselbach's arguments to the contrary.Footnote 15

4. Plural *a-insertion as epenthesis

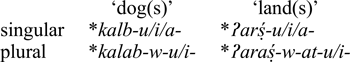

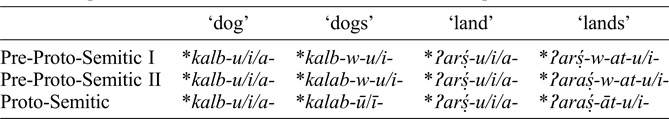

We have established that the *CVCaC-ū- and *CVCaC-āt- plural patterns of *CVCC-(at-) nouns may have been a feature of Proto-Semitic. We have also seen that the external plural suffixes that are characteristic of these patterns should be reconstructed as *-w-u/i- and *-w-at-u/i- for a recent ancestor of Proto-Semitic on internal and comparative grounds. For this stage of pre-Proto-Semitic, we can therefore hypothetically reconstruct this pluralization pattern as follows:

As noted above, it has been suggested that the *a inserted in these forms was epenthetic (e.g. Murtonen Reference Murtonen1964). The reconstruction of a pre-Proto-Semitic plural suffix *-w- creates a plausible environment for this kind of epenthesis to take place. The vowel then serves to break up what would otherwise be a cluster of three consonants. This cluster is created by the addition of the plural suffix *-w- to the stem; in the singular, there is no plural suffix, no three-consonant cluster, and hence no epenthesis. We can therefore reconstruct an even earlier stage of pre-Proto-Semitic, where the plural of *CVCC-(at-) nouns could simply be formed by adding the *-w- plural suffix and plural case endings to the unchanged singular stem. Schematically, the development we propose is shown in Table 2.

Table 2 Epenthesis of *a and elision of *w in the external plurals

The inserted *-a- in the plural is then originally not the morphological hallmark of a distinct plural stem, but the result of a sound change, triggered by the following consonantal suffix. That this reconstructible Proto-West-Semitic pattern can thus be explained from pre-Proto-Semitic implies that it did, in fact, occur in Proto-Semitic and was lost in Akkadian, rather than being a Proto-West-Semitic innovation of unclear origin.

This account explains why *-a-insertion in the plural is characteristic of *CVCC-(at-) nouns. This is the only frequently occurring class of nouns or adjectives in Semitic that ends in two consonants.Footnote 16 In other classes of nouns and adjectives, the conditioning factor – two stem-final consonants, followed by the plural suffix *-w- – was absent, so we do not find the epenthetic *-a- vowel (or any other vowels changing to *a, which we might expect if this were truly a morphological way to mark the plural stem; cf. the processes described for non-Semitic branches of Afroasiatic by Greenberg Reference Greenberg and Lukas1955).

There are a few other words, however, where we may wish to reconstruct a stem-final cluster of two consonants: stems consisting of just two consonants, *CC-, without any vowel. While controversial, we find the arguments for their reconstruction put forward by Testen (Reference Testen1985) convincing.Footnote 17 Based on the seemingly irregular behaviour affecting the words for ‘son’ and ‘two (m.)’ in three separate branches of Semitic (Aramaic, Modern South Arabian, and Arabic),Footnote 18 Testen reconstructs the Proto-Semitic stems of these words as *bn- and *θn-, with an initial consonant cluster. Clusters can then also be reconstructed for other words that show the same behaviour in one or more of these languages as well.Footnote 19

If the *-a- in the plural stem of the *CVCC-(at-) nouns is an epenthetic vowel inserted to break up a consonant cluster, we should also expect it to appear in the words of this *CC- type. Supposing that these also formed their plural by suffixing *-w-, the expected development would be pre-Proto-Semitic I *CC-w-u/i- > pre-Proto-Semitic II *CaC-w-u/i- > Proto-Semitic *CaC-ū/ī-. And in fact, this is exactly what we observe in the word for ‘sons’. While the singular stem can be reconstructed as Proto-Semitic *bn- based on the arguments alluded to above, the plural is marked by an *a-vowel and the ‘masculine’ external plural suffix: *ban-ū/ī-.Footnote 20 This matches the predicted development: pre-Proto-Semitic I *bn-w-u/i- > pre-Proto-Semitic II *ban-w-u/i- > Proto-Semitic *ban-ū/ī-. Here, too, the *-a- in the plural stem can be explained as an epenthetic vowel inserted to break up the consonant cluster created by the plural suffix *-w-.Footnote 21 This confirms that the same insertion in the plural stems of *CVCC-(at-) nouns is phonological in origin, not morphological.Footnote 22

5. Conclusion

In this paper we have provided a solution for the appearance of *a in external plurals of *CVCC- nouns in various Semitic languages. This vowel has previously been considered a remnant of the broken plural system in Northwest Semitic, but we have shown that these *CVCaC-ū- forms can be reconstructed for Proto-Semitic, long before the Northwest Semitic loss of broken plurals. Internal evidence from other lexemes within the Semitic language family as well as comparative evidence from Afroasiatic points towards a pre-Proto-Semitic plural suffix *-w-, which lengthened the following vowel in Proto-Semitic, whether this was a case vowel or part of the ‘feminine’ suffix *-at-. Consequently, we can reconstruct a pre-Proto Semitic plural form *CVCC-w(-at)-u/i-, with a cluster of three consonants. This cluster is a plausible environment for an epenthetic vowel to occur. Hence, we have proposed a development in three stages: pre-Proto-Semitic I *CVCC-w(-at)-u/i- > pre-Proto-Semitic II *CVCaC-w(-at)-u/i- > Proto-Semitic *CVCaC-ū/ī- and *CVCaC-āt-u/i-. Additional support for this derivation comes from a stem consisting of two consonants only, which also had a three-consonant cluster in the plural: *bn-w-u/i- > *ban-w-u/i- > *ban-ū/ī-.

We therefore argue that the *CVCaC-ū- plural pattern is not a Northwest Semitic remnant of the broken plurals, but originated through a pre-Proto-Semitic sound change. Concerning the classification of Northwest Semitic, the existence of *CVCaC-ū- plurals appears to be a shared retention rather than a shared innovation. The nearly complete regularity of this pluralization pattern for *CVCC- nouns in Northwest Semitic may still be a shared Proto-Northwest-Semitic innovation. On the other hand, it may also reflect the loss of the broken plural system in these languages. With broken plurals off the table, *CVCaC-ū- may have been the only common pluralization pattern for these nouns. As this provides a plausible scenario of parallel innovation of the typically Northwest Semitic pluralization system, our suggestion calls into question the strongest argument for a phylogenetic node more closely uniting Ugaritic, Aramaic, and Canaanite within the larger Central Semitic subgroup (cf. Kogan Reference Kogan2015: 228–9).Footnote 23

We have largely bypassed the genuine broken plurals, as we have shown that the forms discussed in this paper are unrelated to them. But we may need to reopen the discussion on their value for the classification of the Semitic languages. Based on the similarity between the *CVCaC-ū- plurals and Akkadian forms which combine a modified plural stem with external plural endings (Huehnergard Reference Huehnergard and Golomb1987a: 181–8), it is now accepted practice to reconstruct a highly productive broken plural system for Proto-Semitic; Northwest Semitic and Akkadian then lost most broken plural forms and added external plural endings to some others. But if we exclude the *CVCaC-ū- plurals, the various stem-modifying pluralization strategies in different branches of Semitic look rather different.

In Northwest Semitic, the examples are mainly limited to a few cases of complete pattern replacement with singular inflection like Biblical Hebrew réḵeḇ ‘chariotry’ (sg. rakkāḇ ‘charioteer, horseman’?) and Syriac ḥemr-ā ‘donkeys’ (sg. ḥmār-ā). It is quite unclear whether these examples should not simply be interpreted as collectives, a category which is distinguished from broken plurals in languages that have them.Footnote 24 The handful of mixed plural formations, with internal stem replacement and external plural suffixes, consists of biradical stems that gain an extra radical in the plural (like Biblical Hebrew sg. ʔām-ā ‘maidservant’, pl. ʔămāh-ōṯ), complete or nearly complete reduplication (like Biblical Hebrew sg. sal < *sall- ‘basket’, pl. sal~sill-ōṯ; Biblical Aramaic m.sg. raḇ ‘great’, m.pl. raḇ~rəḇ-īn), and the well-known example of Biblical Hebrew sg. pésel ‘idol’, pl. pəsīl-īm.Footnote 25

In Akkadian, we find that plurals always take external plural endings. Some nouns additionally mark their plural stem by partial reduplication (sg. alak-t- < *halak-(a)t- ‘road’, pl. alk~ak-āt- < *halak~ak-āt-; sg. ab- ‘father’, pl. ab~b-ū/ī) or suffixation of -ān- or *-āy-.Footnote 26 Pattern replacement in the stem itself is not synchronically attested, although Huehnergard (Reference Huehnergard and Golomb1987a) suggests that this may originally have occurred in the plurals suffixed with *-āy-, but is now obscured by back formation (as with ṣuḫā̆r-û/ê ‘servants’, sg. ṣuḫā̆r- replacing original ṣaḫir-?) or the ambiguity of the cuneiform script (as with a-wi-lu-ú/le-e ‘men’, i.e. awīl-û/ê or āwil-û/ê?, sg. awīl-).

Finally, in the branches sometimes collectively referred to as ‘South Semitic’ – Arabic, Ethiosemitic, Ancient South Arabian, and Modern South Arabian – we find the classic broken plural system, with large-scale unpredictable stem replacement, frequent addition or deletion of a feminine suffix, frequent prefixation of *ʔa-, and a clear distinction between plurals and collectives, but without special plural endings or reduplication (cf. Ratcliffe Reference Ratcliffe1998a).

Having lost the Northwest Semitic *CVCaC-ū- plurals as an intermediate category showing both morphological, non-reduplicative pattern replacement and suffixation, there is little that obviously connects the different internal pluralization strategies in the various subfamilies of Semitic. In the light of our non-morphological explanation of the origin of the *CVCaC-ū- plurals, we therefore believe that the reconstruction of nominal pluralization in Semitic must be reconsidered.