Introduction

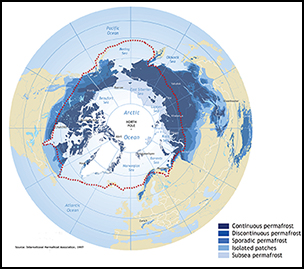

The past decade has witnessed growing global concern about the accelerating impact of climate change on archaeological sites (Colette Reference Colette2007; see online supplementary material (OSM) 1, references 1–4). An increasing number of ancient sites and structures around the world are now at risk of being lost. Once destroyed, these resources are gone forever, with irrevocable loss of human heritage and scientific data. Often defined as the territory north of the +10°C July isotherm, the Arctic (Figure 1) is a bellwether for current large-scale repercussions of climate change, and for the future changes predicted to occur around the world. The Arctic has warmed at a rate of more than twice the global average since the 1980s (Stocker et al. Reference Stocker, Qin, Plattner, Tignor, Allen, Boschung, Nauels, Xia, Bex and Midgley2013). While some historical changes in climate result from natural causes and variations, the strength of current trends indicate clearly that human influences have become a dominant factor (ACIA 2004; Stocker et al. Reference Stocker, Qin, Plattner, Tignor, Allen, Boschung, Nauels, Xia, Bex and Midgley2013). Due to increasing concentrations of greenhouse gasses in the Earth's atmosphere, currently observed climatic trends are predicted to accelerate (ACIA 2004; Stocker et al. Reference Stocker, Qin, Plattner, Tignor, Allen, Boschung, Nauels, Xia, Bex and Midgley2013).

Figure 1. Circum-Arctic map of the distribution of permafrost. The focus area of this article is located north of the +10°C July isotherm (dotted red line) (map by Brown et al. Reference Brown, Ferrians, Heginbottom and Melnikov1997).

Climate change will cause wide-ranging alteration to the Arctic, with some impacts already observable. Rising air temperatures, permafrost thaw, fluctuations in precipitation, melting glaciers and rising sea levels are just some of the changes affecting the natural system (ACIA 2004), and causing physical and chemical damage to archaeological sites and materials. The potential scale of this threat to archaeological sites has led to growing concern among polar archaeologists (Blankholm Reference Blankholm2009; see OSM 1, references 1 & 5). The subject has, however, received limited attention within the wider research community, and little is known about how sites are being, and will be, affected. Here we present the first broad synthesis on the most significant climate change impacts on the Arctic, and describe how these changes are currently affecting archaeological sites. We also give examples of current management strategies and mitigation measures, including awareness-raising initiatives. Finally, we propose the next generation of research and response strategies, and suggest how to capitalise on existing successful connections among research communities and between researchers and the public. Focusing on Alaska, northern Canada, Greenland, northern Norway (including Svalbard) and northern Russia (Figure 1), we also draw parallels with archaeological sites from outside the region.

Arctic archaeological potential

The Arctic's cold and wet conditions have led to the extraordinary long-term preservation of archaeological material, including both artefacts and environmental evidence. The lack of modern development has also left many sites relatively undisturbed. Researchers therefore have unique opportunities to learn about past environments and cultures, many of which connect directly to modern indigenous cultures. Arctic archaeological sites often provide concrete connections to cultural heritage that language and other intangible aspects of culture cannot. Furthermore, they provide an ideal medium through which to engage younger generations with local heritage and culture (Lyons Reference Lyons, Friesen and Mason2016). Spectacular finds and surviving structures have provided many novel contributions to the understanding of our common cultural history (Figure 2). Recent methodological advances are providing new results (e.g. Lee et al. Reference Lee, Merriwether, Kasparov, Khartanovich, Nikolskiy, Shidlovskiy, Gromov, Chikisheva, Chasnyk and Timoshin2018; see OSM 1, references 6–8). The archaeological deposits also contain a diverse range of animal, plant and insect remains, and anthropogenic soils and sediments that enable us to move beyond the human-mediated aspects of the environmental system to address questions within other research fields (Pitulko & Nikolskiy Reference Pitulko and Nikolskiy2012; see OSM 1, references 9–15). Causey et al. (Reference Causey, Corbett, Lefèvre, West, Savinetsky, Kiseleva and Khassa2005), for example, used avifauna from multiple archaeological sites in the Aleutian Islands to model the impact of climate change on regional ecosystems.

Figure 2. Examples of some of the extraordinary archaeological finds from the Arctic: A) ivory owl effigy toggle from Nuvuk, Alaska (photograph by Anne M. Jensen); B) pre-contact driftwood house floor from Kuukpak in the Mackenzie Delta, Canada (photograph by Max Friesen); C) human remains from Qilakitsoq, Greenland (photograph by National Museum of Denmark); D) preserved medieval textiles from Andøy, Nordland, Norway (photograph by Mari Karlstad); E) 31000-year-old decorated ivory scoop from the Yana site, Arctic Siberia (photograph by Vladimir Pitulko).

As there is no official record of the total number of archaeological sites in the Arctic, we collected data from national cultural heritage databases and found that ~180000 sites are currently registered (Table 1; OSM 2). This approximation is, however, somewhat uncertain due to a lack of official site numbers in the Russian Arctic and differences in how ‘sites’ are defined from country to country. Regardless of total number, very few of the sites have been excavated, and we anticipate that many more sites await discovery in those parts of the Arctic yet to be surveyed. Thus, archaeological sites in this region continue to offer great potential for further spectacular discoveries and novel scientific contributions.

Table 1. The number of archaeological sites registered in the focus area of this article. Methods used to provide the numbers are described in OSM 1.

These archaeological sites may, however, be under serious threat from climate change, which is influencing a range of processes that can accelerate site destruction. The following overview is based on a detailed compilation and review of published articles and publicly available reports that identify impacts of climate change on archaeological sites in the Arctic, or that provide information about archaeological resources already damaged by climate change.

The impact of climate change on archaeological sites

Coastal erosion

Sea-level rise, the lengthening of open-water periods due to sea-ice decline and a predicted increase in the frequency of major storms are all expected to intensify erosion of the Arctic coastline (Lantuit et al. Reference Lantuit, Overduin, Couture, Wetterich, Are, Atkinson, Brown, Cherkashov, Drozdov, Forbes, Graves-Gaylord, Grigoriev, Hubberten, Jordan, Jorgenson, Odegard, Ogorodov, Pollard, Rachold, Sedenko, Solomon, Steenhuisen, Streletskaya and Vasiliev2012). Coastal erosion poses a widespread threat to many archaeological sites in this region due to the predominantly coastal lifeways of Arctic people. The permafrost coasts of north and north-west Alaska and the western Canadian Arctic are characterised as one of the largest areas of high-sensitivity shoreline in the circumpolar Arctic (Lantuit et al. Reference Lantuit, Overduin, Couture, Wetterich, Are, Atkinson, Brown, Cherkashov, Drozdov, Forbes, Graves-Gaylord, Grigoriev, Hubberten, Jordan, Jorgenson, Odegard, Ogorodov, Pollard, Rachold, Sedenko, Solomon, Steenhuisen, Streletskaya and Vasiliev2012). While not a new phenomenon in this area, coastal erosion is currently widespread and is greatly affecting the archaeology in the region (Jones et al. Reference Jones, Hinkel, Arp and Eisner2008; Friesen Reference Friesen2015; Gibbs & Richmond Reference Gibbs and Richmond2015; Jensen Reference Jensen, Dawson, Nimura, López-Romero and Daire2017; O'Rourke Reference O'Rourke2017; see OSM 1, references 16–22). Jones et al. (Reference Jones, Hinkel, Arp and Eisner2008), for example, focused on a stretch of the Beaufort Sea coastline near Drew Point in north Alaska, and found that three out of four known archaeological sites had disappeared, with the remaining site heavily damaged by erosion. Furthermore, the coastlines near Barrow on Alaska's North Slope, having been inhabited by semi-sedentary Alaska Natives for at least 4000 years, are quickly being lost to erosion and thawing permafrost (Figure 3). Twenty years ago, rapidly eroding coastal bluffs began exposing human remains at Nuvuk, a key site for understanding the Thule migration across the North American Arctic (Jensen Reference Jensen, Dawson, Nimura, López-Romero and Daire2017; see OSM 1, references 20--21). Since then, sea-level rise, fierce coastal storms and permafrost thaw have removed over 100m of land. This has destroyed several Ipiutak structures, and has heavily eroded a cemetery containing over 100 individuals (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Examples from Walakpa in Alaska of newly exposed archaeological layers that are quickly degrading due to multiple processes (permafrost thaw, frost/thaw processes, microbial degradation and wave action during storms) (photograph by Anne M. Jensen).

The most important archaeological sites of the Inuvialuit—the aboriginal inhabitants of north-westernmost Canada—are endangered by erosion (Friesen Reference Friesen2015; O'Rourke Reference O'Rourke2017). In the Russian Arctic, erosion is severe along the Laptev and East Siberian Seas (Figure 1) (Lantuit et al. Reference Lantuit, Overduin, Couture, Wetterich, Are, Atkinson, Brown, Cherkashov, Drozdov, Forbes, Graves-Gaylord, Grigoriev, Hubberten, Jordan, Jorgenson, Odegard, Ogorodov, Pollard, Rachold, Sedenko, Solomon, Steenhuisen, Streletskaya and Vasiliev2012; see OSM 1, references 23–24), although how this is affecting archaeological sites is virtually unknown. Erosion rates of 5–6m per year have, however, been measured over a 10-year period at the archaeological site of Yana (Pitulko Reference Pitulko, Bickersteth, Watson, Frisen and Hollesen2014). This site represents the earliest-known occupation in the Arctic region (25000 kya) and is a key site for understanding the first peopling of the Americas. Although the Chukchi shorelines (north-west of the Bering Strait) are considered less vulnerable, erosion is still removing local archaeological sites (Dikov Reference Dikov1977; Gusev Reference Gusev and Belova2010; Lantuit et al. Reference Lantuit, Overduin, Couture, Wetterich, Are, Atkinson, Brown, Cherkashov, Drozdov, Forbes, Graves-Gaylord, Grigoriev, Hubberten, Jordan, Jorgenson, Odegard, Ogorodov, Pollard, Rachold, Sedenko, Solomon, Steenhuisen, Streletskaya and Vasiliev2012). The coastlines of the Canadian Archipelago, Greenland and Svalbard are considered stable due to their predominantly rocky nature, the persistence of sea ice throughout the summer season (for the Canadian Archipelago) and because of a strong post-glacial rebound (rise of land) (Lantuit et al. Reference Lantuit, Overduin, Couture, Wetterich, Are, Atkinson, Brown, Cherkashov, Drozdov, Forbes, Graves-Gaylord, Grigoriev, Hubberten, Jordan, Jorgenson, Odegard, Ogorodov, Pollard, Rachold, Sedenko, Solomon, Steenhuisen, Streletskaya and Vasiliev2012). Nevertheless, erosion on a local scale may still be a major threat to archaeological sites, such as Fort Conger on northern Ellesmere Island in Canada, Iita in north-west Greenland and Herjolfnes in south Greenland, where the remains of a Norse settlement are threatened by coastal erosion (Dawson et al. Reference Dawson, Bertulli, Dick, Cousins, Biehl and Prescott2015; see OSM 1, references 25–27). Several sites in northern Norway and Svalbard have also been categorised as threatened by coastal erosion (Flyen Reference Flyen and Holmén2009; see OSM 1, references 28–31).

Permafrost thaw and microbial degradation

Large parts of the exposed land surface of the circumpolar north contain permafrost (perennially frozen ground) (Figure 1). Permafrost often preserves organic archaeological materials, as cold temperatures and high saturation levels slow the decay of organic materials (Hollesen et al. Reference Hollesen, Matthiesen and Elberling2017). Model predictions show that a warmer climate will affect both the spatial extent of permafrost and the depth of the active layer, which thaws during summer (Slater & Lawrence Reference Slater and Lawrence2013; Hollesen et al. Reference Hollesen, Matthiesen, Moller and Elberling2015). An increase in active layer depths in response to warmer temperatures is significant because it exposes the previously frozen soil layers to accelerated erosion, to wet/dry and freeze/thaw cycles and to increased microbial activity (Hollesen et al. Reference Hollesen, Matthiesen and Elberling2017). Studies from north-western Canada, northern Alaska and Siberia show that permafrost destabilisation is leading to severe erosion and landscape change, with dramatic effects on the preservation of archaeological sites (e.g. Solsten & Aitken Reference Solsten and Aitken2006; Jones et al. Reference Jones, Hinkel, Arp and Eisner2008; Pitulko Reference Pitulko, Bickersteth, Watson, Frisen and Hollesen2014; Andrews et al. Reference Andrews, Kokelj, Mackay, Buysse, Kritsch, Andre and Lant2016). In Auyuittuq National Park Reserve, Nunavut, Canada, 24 out of 48 archaeological sites are categorised as being at high risk of soil disturbance (Solsten & Aitken Reference Solsten and Aitken2006). In Russia, the speed of slope erosion (up to 10m per year) is shown to be highly dependent on the ice content of the soil, mean summer temperature and the amount of incoming solar radiation (Pitulko Reference Pitulko, Bickersteth, Watson, Frisen and Hollesen2014). Clear evidence of hydro-thermal erosion has also been reported in Greenland (Hollesen et al. Reference Hollesen, Matthiesen and Elberling2017).

The physical erosion of sites is relatively easy to document by, for example, remote sensing or repeated site visits. It is, however, more difficult to discover, quantify and predict ongoing microbial or chemical degradation of archaeological deposits and similar processes in archaeological wood. These degradation processes have been scientifically documented (e.g. Mattsson et al. Reference Mattsson, Flyen and Nunez2010; Matthiesen et al. Reference Matthiesen, Jensen, Gregory, Hollesen and Elberling2014; Hollesen et al. Reference Hollesen, Matthiesen, Moller and Elberling2015, Reference Hollesen, Matthiesen, Møller, Westergaard-Nielsen and Elberling2016a, Reference Hollesen, Matthiesen and Elberling2017; see OSM 1, references 32–38). The results show that microbial and fungal communities in archaeological deposits and surviving wooden structures have adapted to the cold Arctic environment; they are sensitive to increasing soil temperatures, especially when water is drained and increasing oxygen availability triggers degradation. The deterioration of organic archaeological deposits is accompanied by high microbial heat production. In some cases, this increases soil temperatures, thereby accelerating the decomposition processes and intensifying significantly the impact of climate change (Hollesen et al. Reference Hollesen, Matthiesen, Moller and Elberling2015).

Increasing soil temperatures and changes in the soil's water content are also important in areas without permafrost (Hollesen et al. Reference Hollesen, Matthiesen, Møller, Westergaard-Nielsen and Elberling2016a). Recent studies of organic archaeological deposits in northern Norway indicate that a predicted air temperature increase of 3°C during the twenty-first century could accelerate the overall decay rate by ~50 per cent (Hollesen et al. Reference Hollesen, Matthiesen, Møller and Martens2016b; Martens et al. Reference Martens, Bergersen, Vorenhout, Sandvik and Hollesen2016). This will be highly dependent, however, on the timing of precipitation, the frequency of dry periods and on evaporation rates (Hollesen et al. Reference Hollesen, Matthiesen, Møller and Martens2016b).

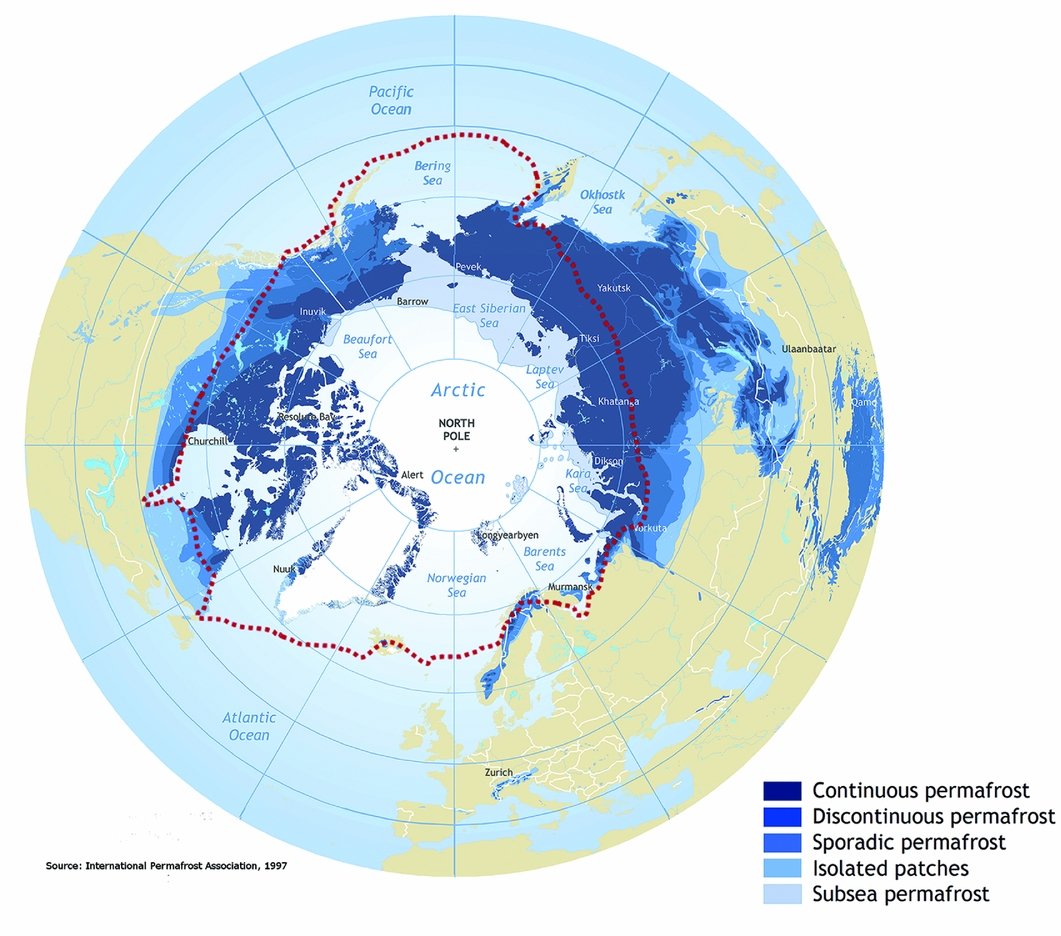

Vegetation increase and tundra fires

Several studies using satellite-based remote sensing and field observations show that the circumpolar Arctic tundra has undergone a ‘greening’ during recent decades (e.g. Tape et al. Reference Tape, Sturm and Racine2006; see OSM 1, references 39 & 40). Over time, climate change is projected to cause a shift in vegetation zones and to promote the expansion of boreal forests into the Arctic tundra, and of tundra into the polar deserts. A direct consequence of vegetation increase is that archaeological sites will become overgrown and eventually hidden (Figure 4). Furthermore, thicker vegetation and the spread of trees will increase summer evapotranspiration (Swann et al. Reference Swann, Fung, Levis, Bonan and Doney2010), which may lower the soil's water content and contribute to the decay rate of organic archaeological deposits (described above). An increase in root depth may also represent a risk to sub-soil archaeology (Crow & Moffat Reference Crow and Moffat2005). When roots exploit the soil for water and nutrients, they may penetrate and cause physical damage to organic archaeological material, including bone and wood (Tjelldén et al. Reference Tjelldén, Kristiansen, Matthiesen and Pedersen2015). Additionally, roots may disturb the archaeological stratigraphy, which is crucial to site interpretations (Tjelldén et al. Reference Tjelldén, Kristiansen, Matthiesen and Pedersen2015). Together with the shift in vegetation, wildfire activity is expected to increase dramatically (Young et al. Reference Young, Higuera and Duffy2017; see OSM 1, references 41 & 42), with strong impacts on permafrost stability and the loss of organic material in the soil (Mack et al. Reference Mack, Bret-Harte, Hollingsworth, Jandt, Schuur, Shaver and Verbyla2011).

Figure 4. The project REMAINS of Greenland is currently investigating the impact of vegetation increase in Greenland. The use of historical photographs is one of the methods used to highlight changes in vegetation (photographs from Austmanndalen near Nuuk in west Greenland by Roussel (1937) and Matthiesen (2016)).

Tourism and the impact of local communities

Climate change is responsible for longer and more extensive seasonal sea-ice melt in the Arctic, which has increased the accessibility of the region. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Stocker et al. Reference Stocker, Qin, Plattner, Tignor, Allen, Boschung, Nauels, Xia, Bex and Midgley2013) predicts that the Arctic Ocean will be nearly ice-free during summers before the end of this century, thereby opening up new shipping routes and extending the use of those that already exist. This will probably drive an increase in the development of coastal infrastructure and cruise tourism (Larsen et al. Reference Larsen, Anisimov, Constable, Hollowed, Maynard, Prestrud, Prowse, Stone, Barros, Field, Dokken, Mastrandrea, Mach, Bilir, Chatterjee, Ebi, Estrada, Genova, Girma, Kissel, Levy, MacCracken, Mastrandrea and White2014). Such changes will open up more archaeological sites to visitors, bringing more traffic into sensitive environments. Improved accessibility to cultural heritage sites—which are often marketed together with the natural landscape as integral parts of the wilderness experience—is already challenging resource managers to balance the use and protection of sensitive sites (Høgvard Reference Høgvard2003; Hagen et al. Reference Hagen, Vistad, Eide, Flyen and Fangel2012). The impacts of uncontrolled or poorly planned tourism on archaeological sites have been well documented in other parts of the world (Markham et al. Reference Markham, Osipova, Lafrenz Samuels and Caldas2016), but there is currently limited information for the Arctic. In Norway, damage to archaeological sites at Kautokeino (Finnmark) and Lake Leinavatnet (Troms County) from all-terrain vehicles, illegal campsites and hikers’ paths has been documented (Blankholm Reference Blankholm2009). Increased visitor numbers to Svalbard has caused clear damage to cultural heritage sites, such as at the early twentieth-century marble mining settlement of London (Hagen et al. Reference Hagen, Vistad, Eide, Flyen and Fangel2012; Thuestad et al. Reference Thuestad, Tømmervik and Solbø2015).

Melting ice, thawing permafrost and coastal erosion is exposing archaeological sites in the Arctic to potential damage not just from tourists, but also from commercial and non-commercial collectors. This includes some local Arctic communities who collect—often legally, but sometimes illegally—artefacts and other archaeological resources found on the ground surface or eroding from the shoreline (Staley Reference Staley1993; Hollowell Reference Hollowell, Brodie, Kersel, Luke and Tubb2006). An increase in this type of collecting should be expected as the erosion of coastal archaeological sites accelerates and melting ice and thawing permafrost expose more remains. There is, however, also the danger of large-scale plundering of archaeological resources, as has been reported in north-east Siberia. Here, high-pressure hydraulic pumps have been used to ‘mine’ concentrations of mammoth remains at kill and butchery sites such as Berelekh, Yana and Buor-Khaya (Pitulko pers. comm., Reference Pitulko, Bickersteth, Watson, Frisen and Hollesen2014; see OSM 1, references 43--44).

Discussion

Our research has reviewed 46 articles and reports that identify impacts of coastal erosion, permafrost thaw, vegetation increase, tundra fires and increased accessibility to archaeological sites in the Arctic (OSM 3). That 42 of these articles are published after 2000 demonstrates the recent increase in evidence of damage to Arctic archaeological sites. The increase may be due partly to a rising awareness of the issues, but it also signals a real increase in the number of sites that are being damaged. In light of both the damage already documented and predicted (Stocker et al. Reference Stocker, Qin, Plattner, Tignor, Allen, Boschung, Nauels, Xia, Bex and Midgley2013), we should prepare for a new reality where archaeologists and heritage managers must deal with a growing number of vulnerable and degrading sites. An effective response to this emerging situation requires the development of new methods and strategies to detect, monitor and mitigate vulnerable sites, and, where necessary, to prioritise between them.

Detecting vulnerable sites

The Arctic contains at least 180000 archaeological sites (Table 1). Very few of these sites have been investigated and we know little about their current state of preservation. It is often assumed that the remoteness and the climate associated with these sites provide protection enough. As the examples highlighted here demonstrate, however, climate change means that this may no longer be the case. Paradoxically, remoteness now compounds the problem: sites far from population centres or popular travel routes cannot be visited often, and may be damaged or disappear completely before being documented. As it is impossible to visit and survey all the sites in the Arctic, new methods to detect and quantify site changes on a regional scale must be developed. This will allow for more effective and targeted site inspection and monitoring or mitigation efforts in the future. Studies have shown that the impact of sea-level rise on archaeological sites can be assessed at a regional scale, using techniques such as remote sensing (e.g. unmanned aerial vehicles or satellite imagery) combined with geographic information systems (GIS) (e.g. Solsten & Aitken Reference Solsten and Aitken2006; see OSM 1, references 45–46). The value of such methods is highly dependent upon the quality of the input data. This can be highly variable for the Arctic, large areas of which remain poorly mapped, with positions and elevations of archaeological sites often inaccurately recorded. This has serious negative consequences for the development of predictive models and assessments that are so vital for effective prioritisation between sites. Reliable estimates for impact rates of erosion, permafrost thaw, vegetation increase and human access are also currently lacking. To a certain extent, however, such estimates have been advanced for the modelling of the natural environment (e.g. Lantuit et al. Reference Lantuit, Overduin, Couture, Wetterich, Are, Atkinson, Brown, Cherkashov, Drozdov, Forbes, Graves-Gaylord, Grigoriev, Hubberten, Jordan, Jorgenson, Odegard, Ogorodov, Pollard, Rachold, Sedenko, Solomon, Steenhuisen, Streletskaya and Vasiliev2012; Slater & Lawrence Reference Slater and Lawrence2013), but the resolution is often too low to be useful for the monitoring of archaeological sites. Furthermore, the physical and chemical composition of archaeological deposits is very different from the natural soils for which such estimates were originally developed. Increased research effort is therefore required to investigate how archaeological sites and artefacts are being affected by ongoing climate change.

Monitoring and mitigation

Monitoring vulnerable sites in the vast and remote Arctic (Table 1) presents an enormous challenge, especially considering the limited number of archaeologists working here. One method to increase capacity in response to this challenge is to work with local people. Scotland's Coastal Heritage at Risk Project (SCHARP), for example, asked volunteer citizen scientists to use a smartphone and tablet applications to assist with the identification and monitoring of vulnerable sites (Dawson Reference Dawson, Harvey and Perry2015). Several other studies have also used vulnerability protocols to monitor the state of archaeological sites (e.g. Daly Reference Daly2014; see OSM 1, references 47–48). If future archaeological surveys in the Arctic were equipped with a standard protocol for evaluating site vulnerability, the systematic data collected could serve as baselines for monitoring change. Observations by archaeologists or local informants will determine the necessity of establishing more detailed environmental monitoring of relevant parameters. The collected data will help to provide a stronger knowledge base for protection and mitigation strategies (Rytter & Schonhowd Reference Rytter and Schonhowd2015; Sidell & Panter Reference Sidell and Panter2016). We currently lack a full understanding of which parameters have the most effect on preservation conditions and therefore of how to set threshold values for when to respond (Martens Reference Martens2016). Although there are many examples of different mitigation measures being applied to protect archaeological deposits from erosion, microbial degradation and vegetation increase (e.g. Rytter & Schonhowd Reference Rytter and Schonhowd2015), such strategies have seldom been applied in the Arctic. This is probably due to the high costs and significant logistical challenges of applying such protective measures here. In some cases, however, low-tech mitigation measures could be an option to slow the degradation processes. Snow fences, for example, could be used to increase the soil-water content, and soil covers could be used to insulate the ground surface. These measures would buffer against variations in soil-water content, and may also prevent erosion, although such measures would require thorough testing before large-scale application.

Rescue and prioritisation of sites

The erosion processes occurring along the north coasts of Alaska, the western Canadian Arctic and in parts of Siberia are already so frequent and destructive that immediate action is needed. Excavations in both Alaska and Siberia demonstrate that anything not excavated will be lost within a few years of exposure (Jensen pers. comm.; Pitulko pers. comm.). Excavations in the Arctic are often more challenging than those in other regions and hence can be very expensive and time-consuming. The existing mechanisms for response—including rescue excavations—are already regularly overwhelmed, and pressures will become more acute in years to come. In addition, conventional science funding models are insensitive to the rate at which sites are now being destroyed. In Alaska, it is already impossible to manage all threatened sites using existing resources. It is therefore essential to find effective methods of evaluating the significance and potential of sites in order to prioritise those that should be excavated and those that must be allowed to decay. Existing methods of prioritising eroding coastal sites in Scotland (Dawson Reference Dawson, Daire, Dupont, Baudry, Brillard, Large, Lespez, Normand and Scarre2013) could be adapted for the Arctic.

The way forward

Awareness of the climatic threats faced by cultural heritage around the world is increasing. A range of ‘bottom-up’ initiatives, such as IHOPE and the Pocantico Call, have emerged (see OSM 3), and several national initiatives aimed at monitoring and responding to the impacts of climate change on cultural heritage have also been developed. The US National Park Service (NPS) established one such approach in 2009. The NPS Climate Change Response Program recognises the need to address the impact of climate on cultural heritage, and to learn from cultural heritage for all areas of climate response (Rockman Reference Rockman2015; see OSM 1, references 49–50). As archaeologists and cultural resource managers produce strategies to handle this growing problem, however, it must be understood that it cannot be engaged effectively by any single organisation or nation. It is therefore crucial that knowledge is shared between cultural resource managers, researchers and those engaged in international projects dealing with the issue of climate effects on heritage. Current scientific projects, such as the Arctic CHAR Project (Canada), REMAINS of Greenland, NABO (Greenland), InSituFarms (Norway) and SPARC (Norway), focus on how archaeological sites and materials are, and will be, affected by climate change in the Arctic (see OSM 3). Financially stretched regional and national research-oriented funding agencies, however, cannot bear the burden of supporting the large-scale, sustained response required to face these challenges. New funding models, staff education and recruitment, public engagement and research must be developed and implemented. Archaeologists and allied scientists must also publicise research on climate threats to cultural heritage, both in scientific journals and in more popular forms. Media coverage, especially in the Arctic, has a key role to play in creating awareness and increasing the public pressure required to direct resources to research and mitigation.

Conclusions

Coastal erosion, permafrost thaw, increasing vegetation, tundra fires and increased accessibility are all part of the broad picture of climate change, with significant implications for the continued preservation of archaeological sites in the Arctic. Each type of impact has different effects, causing damage at timescales varying from days to decades, or even centuries. Consequently, some sites are in immediate danger and others are safe, at least for now. How many sites fall into each of these categories is unknown, so we must develop methods to detect the most vulnerable sites. Methods are also required for effectively managing sites currently characterised as vulnerable. In some areas, it should be possible to monitor sites through the combined use of citizen science projects, vulnerability protocols and environmental monitoring programmes. We must also acknowledge the particular challenges of monitoring such sites, given the size and remoteness of the Arctic. Given that very little has been done to develop methods for mitigation, excavation may seem to be the only currently applicable solution for managing archaeological deposits at risk of degradation. Excavations in permafrost regions are, however, expensive and time-consuming, and archaeologists are already overwhelmed. With the climate continuing to change, this situation will undoubtedly deteriorate. As natural processes are causing the damage, most jurisdictions have no designated funds or programmes for archaeological mitigation. This must change if we are to respond in a serious and efficient manner to the problem of natural threats to heritage. Concurrently, we must be realistic and acknowledge that it will be necessary to prioritise between sites in order to direct limited resources to the most valuable sites.

The current situation in parts of the Arctic clearly demonstrates that we are poorly prepared to respond to a scenario where system-wide, natural processes affect thousands of archaeological sites at once. There are no easy solutions, but the longer we wait, the more difficult the challenges will become.

Acknowledgements

Hollesen and Fenger-Nielsen thank VELUX FONDEN (33813) and the Danish National Research Foundation (CENPERM DNRF100) for financial support, as well as colleagues at the National Museum of Denmark and Greenland National Museum. Callanan thanks the Norwegian Research Council (Miljø 2015) for post-doctoral funding. Dawson thanks Historic Environment Scotland. Friesen wishes to thank the following: Sylvie LeBlanc, Tom Andrews, Susan Lofthouse, Greg Hare, Martha Drake, Stephen Hull and Jamie Brake. Jensen thanks Jeffery Weinberger for his assistance; and the North Slope Borough and Ukpeaġvik Iñupiat Corporation for financial support for work at Walakpa. Markham thanks the J.M. Kaplan Fund, the Barr Foundation and the Rockefeller Brothers Fund. Martens thanks The Research Council of Norway for funding project 212900. Pitulko thanks the Russian Science Foundation for supporting project 16-18-10265-RNF.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2018.8